A Leader Must Give Up to Go Up

Why does an individual step forward to lead other people? For every person the answer is different. A few do it to survive. Some do it to make money. Many desire to build a business or organization. Others do it because they want to change the world. That was the reason for Martin Luther King Jr.

SEEDS OF GREATNESS

King’s leadership ability began to emerge when he was in college. He had always been a good student. In high school, he skipped ninth grade. And when he took a college entrance exam as a junior, his scores were high enough that he decided to skip his senior year and enroll in Morehouse College in Atlanta. At age eighteen he received his ministerial license. At nineteen he was ordained and received his bachelor’s degree in sociology.

King continued his education at Crozer Seminary in Pennsylvania. While he was there, two significant things happened. He heard a message about the life and teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, which forever marked him and put in motion his serious study of the Indian leader. He also emerged as a leader among his peers and was elected president of the senior class. From there, he studied for his PhD at Boston University. It was also during this time that he married Coretta Scott.

SEEDS OF SACRIFICE

King accepted his first pastorate in Montgomery, Alabama, at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in 1954 and settled into family life when his first child was born the next year in November. But that peace didn’t last long. Less than a month later, Rosa Parks refused to relinquish her seat on a bus to a white passenger and was arrested. Local African American leaders arranged a one-day boycott of the transit system to protest her arrest and the city’s segregation policy. When it was successful, they decided to create the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to continue the boycott. Already recognized as a leader in the community, King was unanimously elected president of the newly formed organization.

For the next year, King led African American community leaders in a boycott with the goal of changing the system. The MIA negotiated with city leaders and demanded courteous treatment of African Americans by bus operators, first-come, first-served seating for all bus riders, and employment of African American bus drivers. While the boycott was on, community leaders organized carpools, raised funds to support the boycott financially, rallied and mobilized the community with sermons, and coordinated legal challenges with the NAACP. Finally in November 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the laws allowing segregated seating on buses.1 King and the other leaders were successful. Their world was beginning to change.

The Montgomery bus boycott was a major step in the American civil rights movement, and it’s easy to see what was gained as a result of it. But King also began paying a personal cost for it. Soon after the boycott began, King was arrested for a minor traffic violation. A bomb was thrown onto his porch. And he was indicted on a charge of being party to a conspiracy to hinder and prevent the operation of business without “just or legal cause.”2 King was emerging as a leader, but he was paying a price for it.

THE PRICE KEEPS GETTING HIGHER

Each time King climbed higher and moved forward in leadership for the cause of civil rights, the greater the price he paid for it. His wife, Coretta Scott King, remarked in My Life with Martin Luther King, Jr., “Day and night our phone would ring, and someone would pour out a string of obscene epithets . . . Frequently the calls ended with a threat to kill us if we didn’t get out of town. But in spite of all the danger, the chaos of our private lives, I felt inspired, almost elated.”

King did some great things as a leader. He met with presidents. He delivered rousing speeches that are considered some of the most outstanding examples of oration in American history. He led 250,000 people in a peaceful march on Washington DC. He received the Nobel Peace Prize. And he did create change in this country. But the Law of Sacrifice demands that the greater the leader, the more he must give up. During that same period, King was arrested many times and jailed on many occasions. He was stoned, stabbed, and physically attacked. His house was bombed. Yet his vision—and his influence—continued to increase. Ultimately, he sacrificed every-thing he had. But what he gave up he parted with willingly. In his last speech, delivered the night before he was assassinated in Memphis, he said,

I don’t know what will happen to me now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter to me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. I won’t mind. Like anybody else, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over and I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. So I’m happy tonight . . . I’m not fearing any man. “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”3

The next day he paid the ultimate price of sacrifice.

King’s impact was profound. He influenced millions of people to peacefully stand up against a system and society that fought to exclude them. The United States has changed for the better because of his leadership.

SACRIFICE IS THE HEART OF LEADERSHIP

There is a common misperception among people who aren’t leaders that leadership is all about the position, perks, and power that come from rising in an organization. Many people today want to climb up the corporate ladder because they believe that freedom, power, and wealth are the prizes waiting at the top. The life of a leader can look glamorous to people on the outside. But the reality is that Leadership requires sacrifice. A leader must give up to go up. In recent years, we’ve observed more than our share of leaders who used and abused their organizations for their personal benefit—and the resulting corporate scandals that came because of their greed and selfishness. The heart of good Leadership is sacrifice.

The heart of good leadership is sacrifice.

If you desire to become the best leader you can be, then you need to be willing to make sacrifices in order to lead well. If that is your desire, then here are some things you need to know about the Law of Sacrifice:

1. THERE IS NO SUCCESS WITHOUT SACRIFICE

Every person who has achieved any success in life has made sacrifices to do so. Many working people dedicate four or more years and pay thousands of dollars to attend college to get the tools they’ll need before embarking on their career. Athletes sacrifice countless hours in the gym and on the practice field preparing themselves to perform at a high level. Parents give up much of their free time and sacrifice their resources in order to do a good job raising their children. Philosopher-poet Ralph Waldo Emerson observed, “For everything you have missed, you have gained something else; and for everything you gain, you lose something.” Life is a series of trades, one thing for another.

Leaders must give up to go up. That’s true of every leader regardless of profession. Talk to leaders, and you will find that they have made repeated sacrifices. Effective leaders sacrifice much that is good in order to dedicate themselves to what is best. That’s the way the Law of Sacrifice works.

2. LEADERS ARE OFTEN ASKED TO GIVE UP MORE THAN OTHERS

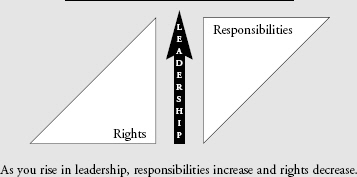

The heart of leadership is putting others ahead of yourself. It’s doing what is best for the team. For that reason, I believe that leaders have to give up their rights. As Gerald Brooks, leadership speaker and pastor, says, “When you become a leader, you lose the right to think about yourself.” Visually, it looks like this:

THE COST OF LEADERSHIP

When you have no responsibilities, you can do pretty much anything you want. Once you take on responsibility, you start to experience limitations in what you can do. The more responsibility you accept, the fewer options you have.

Digital chairman and chief executive Robert Palmer said in an interview, “In my model of management, there’s very little wiggle room. If you want a management job, then you have to accept the responsibility and accountability that goes with it.”4 He is really talking about the cost of leadership. Leaders must be willing to give up more than the people they lead.

For every person, the nature of the sacrifice may be different. Everyone who leads gives up other opportunities. Some people have to give up beloved hobbies. Many give up aspects of their personal lives. Some, like King, give their actual lives. The circumstances are different from person to person, but the principle doesn’t change. Leadership means sacrifice.

3.YOU MUST KEEP GIVING UP TO STAY UP

Most people are willing to acknowledge that sacrifices are necessary early in a leadership career in order to make progress. They’ll take an undesirable territory to make a name for themselves. They’ll move their family to a less desirable city to accept a better position. They’ll take a temporary cut in pay for greater opportunities for advancement. The problem for leaders comes when they think they have earned the right to stop making sacrifices. But in leadership, sacrifice is an ongoing process, not a one-time payment.

If leaders have to give up to go up, then they have to give up even more to stay up. Have you ever considered how infrequently sports teams have back-to-back championship seasons? The reason is simple: if a leader can win one championship with his team, he often assumes he can duplicate the results the next year by doing the same things. He becomes reluctant to make additional sacrifices in the off-season to prepare for what is often an even greater challenge the next year. But today’s success is the greatest threat to tomorrow’s success. And what gets a team to the top isn’t what keeps it there. The only way to stay up is to give up even more. Leadership success requires continual change, constant improvement, and ongoing sacrifice.

Sacrifice is an ongoing process, not a one-time payment.

When I look back at my career, I recognize that there has always been a cost involved in moving forward. That’s been true for me monetarily with every career change except one. When I accepted my first job, our family income decreased because my position paid less than my wife, Margaret, was making as a schoolteacher—she had to give up that job for us to relocate for my new position. Years later when I accepted a director’s job at headquarters in Marion, Indiana, I once again took a pay cut. In 1981 I left that headquarters job to take my third pastoral position, which I accepted without even knowing what the salary would be. (It was lower.) When the board members who offered the job said they were surprised that I took it without knowing what it paid, I said, “If I do the job well, I believe the salary will take care of itself.” And in 1995 when I finally left church leadership after a twenty-six-year career to teach and resource people full-time, I gave up a salary altogether. Why would I do that? Because I knew it would enable me to have greater influence and fulfill a larger vision. Anytime the step is right, a leader shouldn’t hesitate to make a sacrifice.

If leaders have to give up to go up, then they have to give up even more to stay up.

4. THE HIGHER THE LEVEL OF LEADERSHIP, THE GREATER THE SACRIFICE

Have you ever been part of an auction? It’s an exciting experience. An item comes up for a bid, and everyone in the room gets excited. When the bid-ding opens, lots of people jump in and take part. But as the price goes higher and higher, what happens? There are fewer and fewer bidders. When the price is low, everybody bids. In the end, only one person is willing to pay the high price that the item actually costs. It’s the same in leadership: the higher you go, the more it’s going to cost you. And it doesn’t matter what kind of leadership career you pick. You will have to make sacrifices. You will have to give up to go up.

What’s the highest level a person can go in leadership? In the United States, it’s to the presidency. Some people say the president is the most powerful leader in the world. More than any other single person, his words and actions make an impact, not just on the people in the United States but around the globe.

Think about what people must give up to reach the office of president. First, they must learn to lead. Then they have to pay a lot of dues—usually years or even decades in lower leadership positions. Some, like Ulysses S. Grant and Dwight D. Eisenhower, spend an entire career in military service before seeking elected office. Once they have paid their dues and they decide to run for the presidency, every aspect of their prior life goes under the microscope. Nothing is off-limits. It’s the end of their personal privacy.

When they are elected president, their time is no longer their own.

Every statement they make is scrutinized. Every decision they make is questioned. Their family is under tremendous pressure. And as a matter of course, the president must make decisions that mean life or death for others. Even after they leave office, retired presidents will spend the rest of their lives in the company of Secret Service agents who protect them from bodily harm. That is a price not many people are willing to pay.

STANDING ON OTHERS’ SHOULDERS

There can be no success without sacrifice. Anytime you see success, you can be sure someone made sacrifices to make it possible. And as a leader, if you sacrifice, even if you don’t witness the success, you can be sure that some-one in the future will benefit from what you’ve given.

That was certainly true for Martin Luther King Jr. He did not live to see most of the benefits of his sacrifices, but many others have. One such person was an African American girl born in segregated Birmingham, Alabama, in 1954. A precocious child, she followed the news of the day, including civil rights struggles. A neighbor recalls that she was “always interested in politics because as a little girl she used to call me and say things like, ‘Did you see what Bull Connor [a racist city commissioner] did today?’ She was just a little girl and she did that all the time. I would have to read the newspaper thoroughly because I wouldn’t know what she was going to talk about.”5

Though she had an interest in current events, her passion was music. Perhaps her attraction to music was inevitable. Her mother and grand-mother played piano. She began taking piano lessons from her grand-mother at age three and was recognized as a prodigy. Music consumed her growing up years. Even her given name was inspired by music. Her parents named her Condoleezza, from the musical notation con dolcezza, which means “with sweetness.”

Condoleezza Rice is a product of generations of sacrifice. Her grand-father, John Wesley Rice Jr., the son of slaves, was determined to get an education and, according to Condoleezza Rice, “saved up his cotton for tuition” and attended Stillman College in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. After graduating, he became a Presbyterian minister. That was no small accomplishment for a black man in the South in the 1920s. He set the course for the family, whose members were determined to become the best that they could be at whatever they did.

Granddaddy Rice passed his love for education down to his son, also named John, who in turn passed it down to Condoleezza. Her mother’s side of the family was equally industrious and focused on education. Coit Blacker, a Stanford professor and friend of Rice, commented, “I don’t know too many American families, period, who can claim that not only are their parents college-educated, but their grandparents are college-educated and all their cousins and aunts and uncles are college-educated.”6

SACRIFICING TO BE THE BEST

Rice received a broad education at school and at home. She read extensively. She studied French. She took ballet classes. She learned the intricacies of football and basketball from her father, who, besides being a pastor, was a high school guidance counselor and parttime coach. And during the summers when the family went to Denver so that her parents could take graduate courses, she practiced figure skating. But her heart was set on music. While other children were out playing, she was studying and practicing piano.

Her schedule was often grueling. After the family moved to Denver when she was thirteen, she worked harder and made more sacrifices. She was highly disciplined. To be able to compete in both figure skating and piano competitions, she would get up at 4:30 in the morning to fit everything in. One of her teachers commented, “There was a core of her that revealed she knew what she wanted and was willing to make the sacrifices. I think in her mind they were not sacrifices, but things to do that were necessary to keep with her goals.”7And her parents supported her fully and were willing to make sacrifices for her success as well. To assist her in her goals as a pianist, they took out a $13,000 loan (in 1969) to buy her a used Steinway grand piano.

Rice graduated early from high school and went to the University of Denver with the intention of earning a degree in music and becoming a professional concert pianist. It was something she had made sacrifices her entire life to do. But after her sophomore year, she attended the Aspen Music Festival and came to a realization. As hard as she had worked, she might not make it to the top. She observed, “I met eleven-year-olds who could play from sight what had taken me all year to learn and I thought I’m maybe going to end up playing piano bar or playing at Nordstrom, but I’m not going to end up playing Carnegie Hall.”8

GIVING UP TO GO UP

Rice knew that if she was going to reach her personal potential, it would not be in music. So she made a sacrifice few people in her position would be willing to make. She dropped her music major. Her identity had been entirely wrapped up in music, but she was willing to strike out in a new direction. She began searching for a new field.

She found it in international politics. She was drawn like a magnet to the Russian culture and the Soviet government. For the next two years, she immersed herself in her courses, did extensive outside reading, and learned the Russian language. She had found her niche, and she was still willing to pay the price to go to the highest level. After graduating with her bachelor’s degree, she went on to Notre Dame to get a master’s degree. She then returned to the University of Denver and earned a PhD at age twenty-six. When she received an offer for a fellowship at Stanford, she jumped on it. A few months later, she was recruited to become a member of the university’s faculty. She had arrived.

Most people would be happy if the rest of the story played out some-thing like this: publish a few articles, then a book or two; earn tenure; and eventually settle into a comfortable life in the academic community. Not Rice. True, she did carve out a place for herself at Stanford; it was an environment she loved. She enjoyed the intellectual stimulation. She was a talented teacher who found teaching and counseling students highly rewarding. She even became an avid fan of the university’s sports teams. She thrived and received one award after another. She spent a year at the Pentagon in an advisory position with the Joint Chiefs of Staff. She called it a reality check—practical experience that informed her teaching and writing. She was quickly made an associate professor. Rice biographer Antonia Felix writes,

Condi found her passions in Soviet studies and teaching, and her life at Stanford was rich on many levels. She juggled classes, advising, research, writing, playing the piano, weight training, exercising, dating, and gluing herself to the television for twelve-hour football-watching marathons.9

Rice was living an ideal life. She was making the most of her talents, she had great influence, and she was helping to shape the next generation of leaders and thinkers. But then in 1989, the White House called. She was invited to accept a position on the National Security Council as the director of Soviet and East European affairs. She took a leave of absence from Stanford, and it turned out to be a wonderful decision. She was President George H. W. Bush’s primary advisor on the Soviet Union as that government disintegrated. And she helped in creating policy for the unification of Germany. It made her one of the world’s experts on the subject.

She returned to Stanford after two years in Washington. “It wasn’t an easy decision,” Rice remarked. “I felt that it’s hard to keep an academic career intact if you don’t come back in about two years . . . But I think of myself as an academic first. That means that you want to keep some coherence and integrity in your career.”10

Back at Stanford, she possessed even greater clout. In two years she was made a full professor—at age thirty-eight. A month later, she was asked to become provost, a position that had never been held by an African American, by a woman, or by anyone so young. All her predecessors had been at least twenty years older when they took the position, and for good reason. The provost is not only the chief academic officer of the university but is also responsible for its $1.5 billion budget. And Rice was being asked to handle a budget with a $20 million deficit. Though it meant maintaining a grueling schedule and giving up more of her personal life, she accepted the challenge. And she succeeded, turning the budget around and creating a $14.5 million reserve—all while continuing to teach as a political science professor.

AT THE TOP

As the second in command at one of the world’s premier universities, Rice had it made. She had proven herself as an executive. She was already sitting on many corporate boards. And she was in position to become president of any university in the nation. So some people might have been surprised when she stepped down as provost and began tutoring George W. Bush, then governor of Texas, on foreign policy. But it was a sacrifice she was willing to make—one that led to her becoming national security advisor and eventually U.S. secretary of state.

As I write this, Rice continues to serve in that role. What once looked like a sacrifice has made her more influential than ever. When she completes her term, she could return to teaching with great prestige—there isn’t a university in the world that wouldn’t want to have her on its political sci-ence faculty. She could become president of one of the top universities. She could run for the Senate. She could even run for the presidency of the United States. She has been consistently willing to give up to go up, and I have no doubt that she will make whatever sacrifices are necessary to take the next step. That’s what happens when a leader understands and lives by the Law of Sacrifice.

Applying

THE LAW OF SACRIFICE

To Your Life

1. To become a more influential leader, are you willing to make sacrifices? Are you willing to give up your rights for the sake of the people you lead? Give it some thought. Then create two lists: (1) the things you are willing to give up in order to go up, and (2) the things you are not willing to sacrifice to advance. Be sure to consider which list will contain items such as your health, marriage, relationships with children, finances, and so on.

2. Living by the Law of Sacrifice usually means being willing to trade something of value that you possess to gain something more valuable that you don’t. King gave up many personal freedoms to gain freedoms for others. Rice gave up prestige and influence at Stanford to gain influence and impact around the world. In order to make such sacrificial trades, an individual must have something of value to trade. What do you have to offer? And what are you currently willing to trade your time, energy, and resources for that may give you greater personal worth?

3. One of the most harmful mind-sets of leaders is what I call destination disease—the idea that they can sacrifice for a season and then “arrive.” Leaders who think this way stop sacrificing and stop gaining higher ground in leadership.

In what areas might you be in danger of having destination disease? Write them down. Then for each, create a statement of ongoing growth that will be an antidote to such thinking. For example, if you have the mind-set that you are finished learning once you graduate from school, you may need to write, “I will make it my practice to learn and grow in one significant area every year.”