“BECK?” LUCY CALLED OUT.

“Right here,” Beckett said.

Rats have superior night vision, and Lucy quickly made out her brother leaning against the curbstone. They’d moved into the gutter when a human had come clattering down the sidewalk on a skateboard.

“Can you believe it?” Lucy said in hushed wonder.

Frankly, Beckett couldn’t. He would have given very long odds against a solitary squirrel plunging a great metropolis into blackness. But well-informed as Beckett was, there was no way he could have known that the city’s power grid had already been strained to the breaking point, what with the long heat wave and millions of air-conditioners running at full blast. The sudden loss of this critical substation had been the last straw.

Even the streetlamps were out. As Beckett’s eyes adjusted to the feeble moonlight, he made out parked cars across the street, and the faint glitter of windows in the buildings beyond the cars. Then a taxi turned onto the block, and for a moment the headlights hit his sister’s jubilant face.

In the distance people were shouting. Car horns were honking. It was almost as if the humans were celebrating the darkness too. But by the time another passing car’s headlights lit things up, Lucy’s face had turned anxious.

“Do you think Phoenix is okay?” she said.

“Let’s hope,” breathed Beckett.

They climbed back onto the sidewalk and looked up. Thanks to an emergency generator, lights had flickered back on inside the substation. But the outdoor floodlights weren’t connected to it, so the facade was as dark as everything else in the neighborhood. Neither of them could make out the squirrel climbing tail-first down the corner of the building. But just as Phoenix was reaching the sidewalk, a garbage truck swung around the corner, catching him in its beams.

The two rats rushed over.

“You did it!” Lucy cried, giving him a massive hug.

“I wouldn’t have believed it,” Beckett said with something like awe in his voice.

Lucy insisted on hearing all the details then and there. Phoenix left out the part about the level hitting him on the head and tail but did his best to reproduce the popping and sizzling sounds.

He was telling them about sliding down the support wire in the dark when a pair of Con Ed vans came tearing around the corner and squealed to a stop. The three rodents cowered back against the building as humans jumped out and pounded up the substation’s front steps. When the doors slammed behind them, Lucy said they had to go tell the others.

“They’re not going to believe it!” she cried.

* * *

But the other wharf rats didn’t need to be told. Most had remained out in front of the pier, too antsy to go to bed, and witnessed the plug being pulled on the city lights. Young rats danced in celebration. Older ones looked around hopefully at their beloved home. Junior’s mother, Helen, who’d been toying with the idea of abandoning her beautiful crate and following her mate and son down to Battery Park, decided to stay put. Two of the elders raced back into the pier to wake Mrs. P. with the amazing news.

Mrs. P. accompanied them back outside to see for herself. “I have to admit, when I first saw that sorry-looking creature,” she said, “I’d never have guessed he could pull off something like this.”

“With the lights out, you can see the stars!” chirped one of several young rats who’d climbed onto the backhoe’s shovel.

“You’re right,” said Mrs. P. She pointed. “That constellation over there is called the Great Rat.”

“Maybe we should rename it the Great Squirrel!” cried another shovel-percher.

“Not a bad idea,” Mrs. P. mused. “Though we mustn’t forget that Lucy and Beckett played their parts.”

The same young rats who’d grumbled when she brought Lucy and Beckett up onto the cleat now chanted their names along with the squirrel’s. But when the three failed to reappear, the chanting turned to worrying. What if they’d sacrificed their lives at the substation? And another thing: the humans needed to be reminded who had shorted the grid. If Beckett didn’t come back, they wouldn’t be able to write any more messages, and the whole enterprise would be in vain.

* * *

In fact, Lucy and Beckett and Phoenix were just on the other side of the West Side Highway. But with no electricity the traffic signals weren’t working, so the flow of cars never quite stopped. They had to wait so long that Phoenix’s exhilaration from his adventure turned to exhaustion, and he actually dozed off on his paws. When a traffic cop finally arrived and halted the traffic, Lucy had to shake Phoenix awake so they could scurry across.

The heroes’ welcome they received would have been nicer for Phoenix if he hadn’t been so dog-tired. When the rats asked if there was anything in the world he wanted, all he could do was yawn and say, “Well, I could use a little snooze time.”

Beckett echoed the yawn and the sentiment. At that point even Lucy was flagging. But Mrs. P. wouldn’t let them retire just yet. Phoenix had to get the notice down from the pier door, Beckett had to fetch the pen, Lucy the box of matches.

When all three were back from their errands, Beckett crouched on the bill, pen in paw, and Mrs. P. struck a match. It fizzled out before Beckett wrote anything.

“Tell me when you’re ready, dearie,” Mrs. P. said.

Beckett thought. When he gave the nod, Mrs. P. struck a second match. Below his previous message Beckett scrawled: We warned you!

After tacking the notice back up on the door, Phoenix was finally able to drag himself off to his papery nest, with Beckett right behind him. As the other rats dispersed, Lucy started to help Mrs. P. home, but Mrs. P. went no farther than just inside the pier door.

“I think I’ll keep a watch on these machines,” she said. “Be an angel and fetch my cushion, would you? And a smidge of cheddar?”

Lucy got her a cushion and a chunk of cheddar and sat with her awhile. “Do you think the power outage will stop them?” she asked.

“We can only hope,” Mrs. P. said, breaking off a piece of cheese for Lucy. “But even if it doesn’t, the three of you deserve a lot of credit. Now at least we have a fighting chance.”

“It was all Phoenix. You should have seen him climb that building! And the wire at the end of the flagpole!”

“Wise of you to pull him out of the drink in the first place. But what’s become of your admirer?”

“Junior? His father took him off to Battery Park so they wouldn’t get blown up.”

“Our sword-wielding sergeant at arms,” Mrs. P. said wryly. “Have you noticed how the ones who feel the need to carry weapons are usually cowards at heart? But now off to bed. You must be dead on your paws.”

When Lucy got back to the crate, Phoenix and Beckett were already sound asleep, and soon she was too. They woke in the morning and joined most of the pier’s older rats, who were gathered around Mrs. P. by the sliding door. Outside, the bulldozer’s plow was glinting in the sun, but nothing else had changed since the middle of the night.

It wasn’t long, however, before a pickup truck pulled up by the fence. With the power outage, most of the demolition crew, like most New Yorkers, were spending the day close to home. But there had been reports of looting and vandalism around the city, so the crew chief had decided to swing by to check the site. He came through the gate and walked around the machines. As he was about to head back to his pickup, the notice on the door caught his eye. He came over—and gawped. After a minute he pulled out his phone and had an animated conversation with his brother-in-law, who happened to be a journalist. Then he took another photo of the notice and sent it to him, along with the first one.

Once the human drove away, the consensus among the rats was that he’d taken Beckett’s warning to heart. Most went back to their crates, Beckett and Phoenix included, but Lucy, who’d noticed that a lot of the young rats were missing, figured they’d gone for a swim and went to join them. However, the only creature anywhere around the half-submerged dock was a solitary gull on a piling.

When she got back to the crate, Beckett was too absorbed in an out-of-date New Yorker to care what had become of the younger set. But it wasn’t long before one of the rats in question appeared in their doorway.

“Okay if we come in?” he asked.

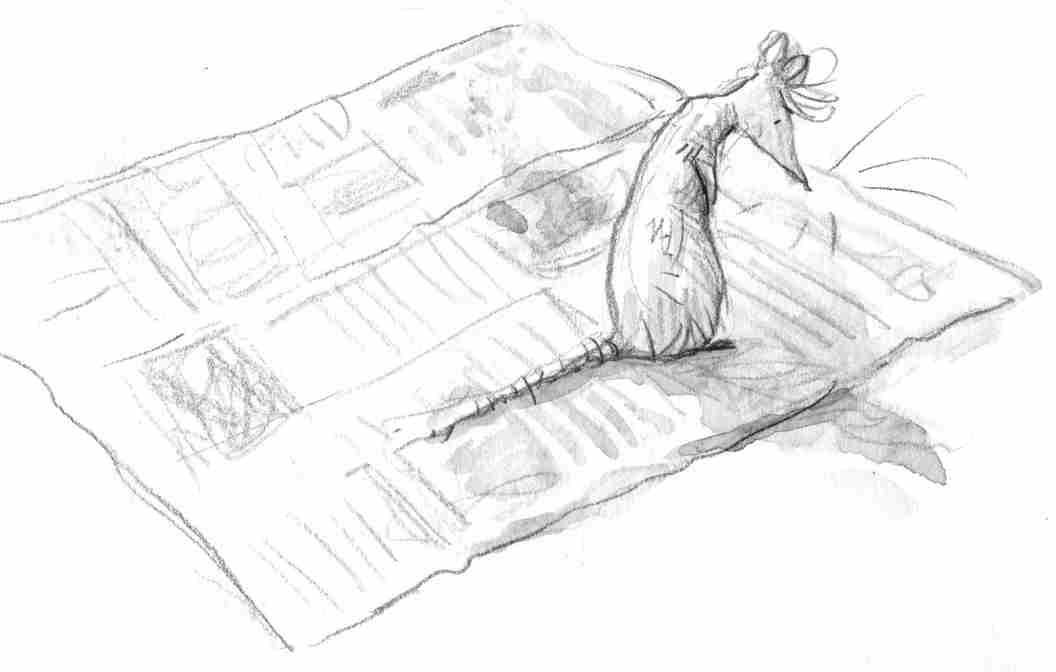

Lucy was too flustered at the thought of guests seeing their crate to formulate a quick answer, so Beckett asked what they wanted. By way of answer the rat dragged in a copy of that day’s Daily News.

“Where’d that come from?” asked Beckett, perking up.

“A deli,” said the young rat. “They had all the papers.”

“Um . . . would you mind if I look at it?”

“We got it for you.”

“For me?” Beckett said, flabbergasted.

Another young rat came in with a plastic-wrapped slab of cheese for Lucy. Next came Emily, petite as she was, singlehandedly rolling a can of nuts for Phoenix. The young rats had gone on a foraging expedition. For many of them it had been their maiden voyage across the West Side Highway, but they’d reached it just as a policeman stopped the traffic. They’d been lucky in their choice of deli, too. The poor owner was so busy dealing with the melting ice cream in the freezer unit that the rats had the pick of the rest of the store. They hadn’t grabbed goodies for themselves, however—only for Lucy and Beckett and Phoenix. The threesome grinned at each other, then at the others. They knew a peace offering when they saw one.

The cheese, a kind of Swiss called Gruyère, was unquestionably the best thing Lucy had ever tasted. Phoenix felt much the same about his offering: mixed nuts again, but this time deluxe mixed nuts. Beckett was so pleased with the newspaper that he gave in to the young rats’ pleas to read it to them. Since there wasn’t room for everyone in the cramped crate, Beckett took the paper out to Mrs. P., who was still by the pier door. As everyone gathered around, he started with the headline—BLACKOUT!—in white letters across an inky black front page. Then he turned to the article on page two and read:

“ ‘Shortly before 11:00 last night a major power outage crippled all of Manhattan and parts of Queens and the Bronx. According to a Con Edison spokesperson, the long heat wave had severely overloaded the grid.’ ”

“What’s a spokesperson?” someone asked.

“A person who speaks,” Beckett said.

“I thought Phoenix made the lights go out,” said someone else.

“He did,” said Beckett. “They just don’t know it yet.”

“Keep going,” said another.

Beckett read on:

“ ‘The mayor is petitioning for state and federal assistance.’ ”

“What’s federal?” someone asked.

Beckett had no clue, so he kept reading:

“ ‘While Con Edison crews are working round the clock to restore power, the elderly and infirm are advised not to overexert themselves in the heat. There may be some relief in sight on that score. Thunderstorms are predicted for later today.’ ”

“Thunderstorms, cool!” said a young rat.

“Hey, Phoenix,” said another. “After lunch, could you give us a climbing lesson?”

The inside of the sliding door soon became a climbing wall. Rats aren’t built for climbing as squirrels are, so despite Phoenix’s tips, there were a lot of tumbles. But the spectacle made Mrs. P. quiver with amusement, and most of the young rats enjoyed themselves too, bruises and all.

That night, slashes of lightning lit up the city’s skyline, and rain splattered down through holes in the pier roof. When it was still raining in the morning, the younger set wanted more climbing lessons. This time Lucy joined in. Though Mrs. P. insisted the rats fetch the spare cushions from her parlor to make a softer landing place, Lucy didn’t need them, being one of the few who never fell.

Beckett naturally avoided all this exertion, but when the sun finally broke through the clouds, around noon, he did go out to look for a newspaper. Junior and his father watched him leave the pier. They were huddled under the backhoe, shamefaced and drenched, having spent the pitch-black night under a dripping bench in Battery Park. Once Beckett crossed the jogging path, they crept out along the beam on the side of the pier, slunk in by the back crack, and climbed up to their crate. Helen let Junior slip in but blocked the doorway on Augustus, who scrabbled back down and burrowed into the fuel pile by the metal drum.

Junior dried himself off, spruced himself up, and broke a chunk off his father’s prize ball of provolone cheese. But when he looked out the doorway and saw the climbing lesson, he lost his appetite. There was Lucy, her eyes glued to the mangy instructor. So were Emily’s. Junior felt like chucking the provolone at Phoenix, but no doubt attacking the big hero would only add to his disgrace.

When Beckett came back with the paper, he looked almost excited, so the climbing lesson instantly broke up. Today’s front-page headline was SMELL A RAT? Under it were two photos: one of the notice with Beckett’s first message written on it: Dear Humans, Please quit putting out poison and leave our pier alone. We are peace-loving creatures but if you try to carry out your plan you will regret it. The other photo was of the notice with Beckett’s added message: We warned you! The lead article began at the foot of the page.

“ ‘Early this morning Con Edison restored service to neighborhoods in Queens and the Bronx and all of Manhattan above Thirty-fourth Street,” Beckett read out in his soft voice, “but lower Manhattan remains without power. Yesterday we speculated that the outage was caused by an overloaded grid. However, a strange turn of events has come to our attention that may point the finger in a different direction. Preposterous as it may sound, this blackout, which has already caused New Yorkers untold misery and cost the city’s economy untold billions, may be the work of rats.”

The rats gaped at Beckett, then let out a hearty cheer.

“Maybe those humans aren’t as dumb as they look,” one of them said.

“What’s ‘preposterous’?” asked another.

“I think it means ‘hard to believe,’ ” said Beckett.

“What’s ‘billions’?”

“A lot,” said Mrs. P. “Go on, Beckett.”

He kept reading:

“ ‘The crux of the matter may well be a dilapidated west side pier slated to be turned into a new tennis facility. The demolition crew arrived there on Monday to find a message on a bill that had been posted earlier on the pier door (see top photo). The pier was already suspected to be infested with rats, but not surprisingly, the crew wrote off the message as a prank. That night: the blackout. Yesterday the crew chief returned to the site and found a postscript added to the message (see photo directly above). Of course, it may well be a hoax. To the best of our knowledge, rats are no more capable of writing messages than they are of causing citywide power outages.’ ”

This got a good laugh from the rats. Even Beckett chuckled as he turned the page. He lifted page two to show a grainy photo.

“Look familiar, Phoenix?” he asked with a mischievous grin.

The photo was of the level lying across the two coils in the upper part of the substation. As rats chittered and clapped Phoenix on the back, Beckett read on:

“ ‘The immediate cause of the blackout was the breakdown of an important Con Edison substation. And the cause of the breakdown was a piece of metal, a level, making contact with two high-voltage coils (see photo). According to a Con Ed spokesperson, no one at the station had been in proximity to these coils that evening, which leaves us with the mystery of how the level got there. Could the substation have been sabotaged by vigilante rats? “You can’t be serious,” said Mr. P. J. Weeks, the developer behind the pier project. The Con Ed spokesperson wasn’t quite so dismissive. “Well, it doesn’t seem very likely,” she said. “But we can’t rule out anything till we’ve gone through all our surveillance video.” In the meantime, the substation remains offline, and lower Manhattan remains in the dark.’ ”

The rats stomped their paws and swished their tails triumphantly. Once the spontaneous celebration subsided, however, Mrs. P. felt compelled to warn them against letting their guard down.

“And I think we’d better open this little gift they left us,” she said.

She led them over to the trunk of explosives. It was locked with a padlock, and the edges and lock were metal, but the sides were made of a composite material that looked more vulnerable. So Mrs. P. had all the younger rats smile and then proceeded to divide them into gnawing details. She exempted Lucy and Beckett and Phoenix, since they’d done so much for the cause already, but while Beckett went happily back to perusing the paper, Lucy joined one of the details anyway, as did Phoenix. He’d been eating only shelled nuts lately and needed to wear down his front teeth again. He also enjoyed the teamwork—and admired it. In fact, he was beginning to have a sneaking admiration for this whole pier community. He supposed Great-Aunt Flo played a role sort of like the elders, but in the woods there were no elections. They had no real leader, and if humans threatened to chop down all the trees, he was sure the squirrels would be too unorganized to do anything but scatter. Forming a united front against a common foe would be completely beyond them.

It took him and the other gnawers most of the afternoon, but they finally made a small puncture in the trunk. Once there was a hole, it was relatively easy to enlarge, and by dusk they had an opening that any of them other than Mrs. P. could have squeezed through. However, the trunk’s contents blocked the way.

“Looks like candles,” said Mrs. P, pulling one out.

It was red and waxy with letters stenciled on the side.

“ ‘Dynamite,’ ” Beckett read. “The wick may be a fuse.”

They emptied the trunk of twenty-four small sticks of the dynamite. The first idea was to dump all of them off the dock, but when a rat proposed using them to blow up the humans’ machines, it was too tempting to pass up. They pushed two sticks of dynamite and the box of matches under the door. It was twilight now. The skyline to the north was lit up again, but their part of the city was still dark. After placing the dynamite under the bulldozer, between the shovel and the steel treads, young rats argued over who would get to light the fuse. Mrs. P. put an end to that. If anyone was going to get blown up, it would be her. She shooed them all away and did the honors herself.

After lighting both fuses, she dropped the match and waddled away as fast as she could. But the dynamite was only meant for weakening beams, and the blast wasn’t much louder than a car backfiring. Mrs. P. felt the explosion in her old bones, but it didn’t leave a scratch on the bulldozer.

The rats fell back on the original plan. Phoenix pitched in, helping Lucy drag one of the sticks out the pier’s back crack. As the pile by the trunk dwindled, Mrs. P.’s pack-rat nature got the better of her. Her collection included candle stubs, but nothing like this. She surreptitiously settled her bulk over two of the sticks, like a hen on a pair of eggs.

The young rats were having a ball tossing the other sticks of dynamite into the river, so Mrs. P. would have been able to cart hers off to her gallery unseen if only Beckett hadn’t remained with his paper. Though she admired his literacy, she wished he’d go read in his crate. But when she finally lost patience and carried her booty away, Beckett was so engrossed in an article in the Metro section—“Escaping the Rat Race,” it was called—that he didn’t even glance up.