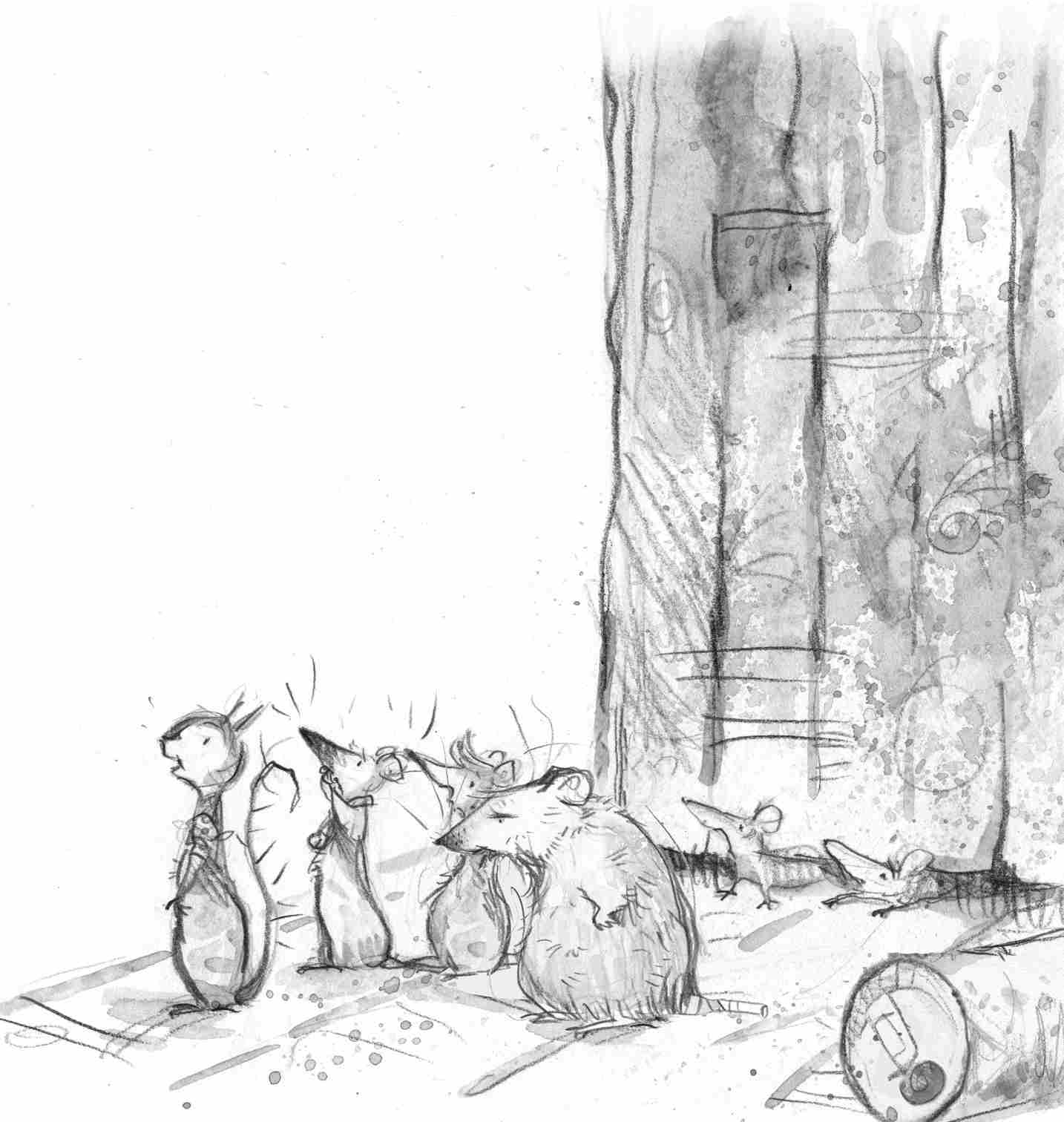

THE VOTERS STARTED CHITTERING AMONG themselves, making so much noise that none of them heard the flapping sound overhead. But Phoenix did. Unlike the rats, he’d been lectured his whole life about watching out for birds of prey, and though he hadn’t done a very good job of it, his two lapses had at least taught him something. Unfortunately, he had nowhere to duck for cover. Hordes of rats hemmed him in on his left and right, while in front of him was a big cleat, and behind him, a beer can.

In another instant the rats heard the wing beats too, and looked up to see a huge hawk descending on them. Most froze in terror—but not the two mayoral candidates. Augustus dropped his sword with a surprisingly high-pitched shriek, leaped off the cleat, raced right around his constituents, and dove under the pier door. Beckett jumped off the cleat and threw himself over his sister to shield her from the bird’s talons.

But the talons didn’t grab him or Lucy or anyone else. With a great flapping of wings the bird settled on the vacated cleat. At that point most of the rats had recovered from their shock enough to start rushing toward the pier, and in the melee the eldest elder got knocked over. As his two fellow elders dragged him toward the pier door, Phoenix called out: “Don’t worry! He’s a friend of mine!”

This had little effect on the fleeing rats. Phoenix gave a shrug and turned to the bird, the very red-tailed hawk who’d grabbed him twice in the past.

“Morning, Phoenix,” said Walter, rearranging his tail feathers so the missing ones were less noticeable.

In his rush to protect Lucy, Beckett had knocked her over, and they lay tangled on the ground, while their father was pressed flat behind his beer can.

“These are friends of mine,” Phoenix said as the three got shakily to their paws. “Lucy, and Beckett, and their father, Mortimer.”

“Nice to meet you, rats,” Walter said with a slight inclination of his head.

None of the three said a word. Face-to-face with a hawk, even Mortimer was struck dumb.

“You really never cease to amaze,” Walter said, turning back to Phoenix. “When the whole city went dark on my way home the other night, I nearly fell out of the sky.”

Lucy wondered if this was the same hawk she and Beckett had seen from the pier roof, flying north with empty talons. But when she tried to ask, nothing came out.

“Inexcusable of me to dump you and fly off that way,” Walter went on. “It’s been eating at me.”

“Don’t give it another thought,” Phoenix said. “Without you I could never have gotten above that cornice. You were instrumental in saving our—their home.”

As rats inside the pier caught the tenor of the conversation, some began to venture back out, though not very far.

“Glad to hear it,” Walter said. “But when I think what that jet engine would have done to me . . .” A shudder rippled his feathers. “Anyway, I stopped by to offer you a lift.”

“A lift?” Phoenix said.

“I owe my old mother another visit. I’d be more than happy to drop you in Manahawkin.”

“What’s Manahawkin?” Lucy asked, finally finding her voice.

“Where I’m from in New Jersey,” Phoenix said.

“I’ll take you right back to that pretty little pond,” Walter offered. “Maybe that pretty little squirrel will still be there waiting for you.”

Giselle! Phoenix hadn’t thought of her in days. He wondered if she’d gone back to the pond from time to time to think about him. It didn’t seem likely. She’d switched from Tyrone to him so easily, she would probably have switched to another squirrel by now. Though she had seemed to like him. You have a wonderful tail, she’d said. In the sunlight you can see a little auburn in it. Aware of the sun on his tail now, he glanced around at it and almost gagged. Giselle would take one look at him and run!

And yet, monstrous as he was, most of these rats were looking at him with admiration. Lucy especially.

“Don’t go, Mr. Phoenix!” said the young rat who’d chased the foil ball.

This ignited an outcry against his leaving. When one rat shouted, “Phoenix forever!” it turned into a chant that would have gone on and on if Beckett hadn’t opened his mouth again to speak.

“You know, Phoenix, you haven’t done so badly here,” Beckett said. “All those articles about you in the papers.”

“Articles in the papers?” Walter said.

“And photos!” another rat cried. “Phoenix is famous!”

Hearing this ruffled Walter’s feathers a bit, reminding him of his celebrity cousin. He squinted up at the sun and commented that it was almost noon.

“If I’m going to get all the way to Cape May today,” he said, “I better be taking off. Want to come along, squirrel?”

As Phoenix glanced around, the wharf rats all shook their heads, silently coaxing him not to go—even Junior.

“Don’t forget, Mrs. P. mixed up that pilatory for you,” Lucy said. “I bet it’ll bring your fur back.”

“I was hoping you’d be staying with us at her place,” Beckett said. “It’s very spacious up there.”

Lucy didn’t add anything to this, but the look on her face was quite eloquent, and when the young rat who’d kicked the foil ball took hold of his tail, Phoenix felt himself surrendering.

“I appreciate the offer, Walter,” he said, “but I think I’ll stick around.”

Rats applauded and high-fived as Lucy and Beckett beamed.

“I wouldn’t have minded the company on the flight,” the hawk said, “but suit yourself.”

“Would I be overstepping to ask you a favor, Walter?” Phoenix asked.

“Of course not. You saved my life.”

“Could I ask you one too, Beckett?”

“Name it,” Beckett said. “You saved our home.”

Phoenix scurried into the pier and fetched a scrap of paper and a pen from Lucy and Beckett’s crate. When he got back outside, he asked Beckett to write something for him. Beckett took up the pen, and Phoenix dictated his note:

“Dear Mom and Dad, I wanted you to know I’m okay. I just relocated to Manhattan.”

This was the one thing that was really bothering him about declining Walter’s offer: the thought of his poor parents mourning his death. Walter and Mortimer looked on in amazement as Beckett scrawled the message on the piece of paper. “Relocated” and “Manhattan” were tricky, but he managed them.

“Anything else?” Beckett asked when he finished.

Phoenix nodded. “Maybe you could put: I miss you. I’ll try to visit someday. Love, Phoenix.”

Other than leaving the e out of Phoenix’s name, Beckett completed the note in style. “Can your parents read?” he asked, handing it over.

“Not that I know of,” Phoenix said. But he had a feeling Great-Aunt Flo might be able to, since she’d taken the trouble to line her nest with newspaper rather than leaves. “You could find the pond where you snatched me, right?” he said, passing the note up to Walter.

“Of course,” Walter said, taking it in his left talons.

“In the woods just north of it there’s one white tree. A birch. Could you drop that at the foot of it?”

“With pleasure,” Walter said.

Phoenix thanked him and offered to get him a nut or two for his trip.

“Nuts aren’t really my thing,” Walter said. “Though I don’t mind the occasional rodent.”

As Mortimer hit the deck again, the rats who’d ventured out fell over each other trying to get back into the pier.

“Just kidding,” Walter said.

With that the hawk unfurled his mighty wings and flapped up into the sky. Mortimer got to his paws again, muttering under his breath. Most of the other rats edged back outside to catch the spectacle of the great bird’s departure. As Walter flew out over the river, a flock of gulls following a charter boat squawked and cleared his path. Gradually the hawk gained altitude. When he veered south, Phoenix felt a pang of regret. But soon rats were crowding around him, and every time one of them clapped him on the back, it knocked a little more of the regret out of him.

Once Walter was completely out of sight, Augustus came rushing out of the pier with a plastic straw in one paw and a pebble in the other.

“I got a peashooter!” he cried. “Where’s the bird?”

“As if you didn’t know, you old charlatan,” Mortimer said with a snicker.

Ignoring the comment, Augustus climbed onto the cleat and squinted left and right as if searching for his foe. “Looks like he skedaddled,” he said. “Lucky for him. I guess we can get back to the business at hand.”

By this he evidently meant the mayoral election. Beckett put up a struggle, but Phoenix and Lucy managed to push him onto the cleat again. The eldest elder was still too shaken up from his tumble to officiate, so the middle elder did the honors, directing those for Augustus to his left and those for Beckett to his right. There wasn’t a rat among them who’d failed to note the candidates’ very different reactions to the hawk, and not even Helen and Junior hesitated to move to Beckett’s side. As Augustus gaped at his totally empty section, the straw and pebble slipped from his paws.

Lucy and a bunch of other young rats pulled Beckett off the cleat and carried him into the pier at the place where the door was warped up. Most of the others followed, and as the rats’ eyes adjusted to the interior dimness, a great majority of them saw their rundown home with a fresh fondness. They gathered around the steel drum, where Beckett had been set down. He’d had enough attention for one day and would have toddled off to his crate if there hadn’t been so many expectant faces turned toward him. He looked to the elders for a hint.

“You might want to appoint new elders, Mr. Mayor,” the youngest of them suggested.

“What’s wrong with you three?” Beckett asked.

“Old Moberly appointed us,” said the eldest, who was leaning on the middle one.

“Could I reappoint you?” Beckett asked.

“Certainly,” the eldest said. “But you shouldn’t feel you—”

“Great,” Beckett said. “You’ll do beautifully. Anything else?”

The elders were quite tickled. After another consultation the youngest said: “There’s also the question of a sergeant at arms.”

Rats looked around. As it happened, their former sergeant at arms was already halfway to Battery Park, but Augustus’s wife and son were just inside the pier door. Helen had stopped Junior there to discuss their future. Forsaking their crate was a bitter prospect to her, but so was remaining on the pier as an object of pity after her spouse’s disgrace. Though Junior didn’t feel the humiliation quite as keenly as he did the bruises from his fall, he figured he had to stick by her, whatever her decision.

The two weren’t far from the place where the pier door was warped up. A moment later Phoenix appeared there, rolling in the can of New Amsterdam ale. Mortimer, who’d talked him into pushing it the last leg, followed with Augustus’s straw wrapped in his tail. “Hey, Phoenix!” Beckett called out. Phoenix eased the can to a stop.

“You’re good-size,” Beckett said. “How’d you like to be sergeant at arms?”

“Um, it should probably be a rat,” Phoenix said.

Beckett looked to the elders again. “That is the tradition,” said the eldest.

“Could he at least be a special advisor?” Beckett asked.

The elders raised no objection this, and when Phoenix didn’t either, Beckett asked his advice about the sergeant-at-arms position.

“Lucy’s strong,” Phoenix pointed out.

“Oh, but I need her as my other special advisor,” Beckett said.

Lucy smiled at this, quite sure her brother would dump most of the mayoral duties on her. “If you want my advice,” she said, “how about Junior?”

“Yeah, he nearly made it up the substation,” Phoenix agreed.

Junior went slack-jawed, and when Beckett beckoned him over, he was too stunned to move. They’d never exactly been pals. But his mother grabbed his paw and pulled him toward the others.

“Would you accept the appointment to sergeant at arms, Junior?” Beckett asked formally.

Helen wasted no time in pushing her son toward the new mayor. As she watched the two young rats shake on the deal, a terrible weight slid from her shoulders.

“Any other pressing duties?” Beckett asked the elders.

They couldn’t think of any, and after all the drama of the last few days, it dawned on everyone that life could go back to normal. While Beckett made a beeline for his crate, Helen virtually floated up to hers, and those who’d packed up for the evacuation happily lugged their bundles back to theirs. The new sergeant at arms tried to talk the younger set into a swim. His soreness had miraculously disappeared.

“I can’t wait to see you dive!” Emily cried.

“I can’t do a really high dive,” Junior said. “Come show us how it’s done, Phoenix.”

“Height’s not as important as form,” said Phoenix. “Your form is much better than mine.”

The two locked eyes for a moment, and they both grinned. “Come on, Lulu,” Junior said. “Let’s all go.”

But to Emily’s relief, Lucy wanted to help Beckett move their beds to Mrs. P.’s. Phoenix offered to help Lucy carry her loafer, which was a good thing, since Beckett was totally preoccupied, agonizing over whether to bring a dog-eared National Geographic to their new digs. Mrs. P. was sound asleep and didn’t even twitch as they maneuvered the shoe up the stirring stick. After they set it down upstairs, Phoenix had a chance to check the place out. Having grown up among majestic pines, he never would have believed he would choose to be stuck in a crate, but this upstairs apartment really didn’t seem too bad.

They went back for Beckett’s loafer. By the time they’d brought over Phoenix’s nesting material, it was Phoenix’s turn to worry about the half-eaten Babybel in Mrs. P.’s lap. But when he gave her a little shake, she opened her eyes with a smile and said, “You’ll be wanting that pilatory, won’t you? It’s by the stove.”

Phoenix fetched the thimble full of ointment from the infirmary.

“Rub it in all over before bed,” Mrs. P. said.

“That’s so nice of you,” he said, eyeing the precious stuff.

“Nothing compared to what you’ve done for us, dearie.”

After depositing the thimble by his nest upstairs, Phoenix came back down and followed Lucy to her old crate. Mortimer was lounging in his shoe. He’d opened the beer can and was sipping some out with Augustus’s straw.

“Sorry you’re all moving out,” he said, sounding anything but sorry.

Lucy spent the rest of the afternoon helping Beckett sort through his reading material. Beckett wasn’t a fast reader and knew perfectly well he would never be able to get to most of it, but he couldn’t bear to part with anything that might prove interesting, so the stack for the fuel pile remained paltry. Meanwhile, Phoenix carried the Gruyère and the nuts over to their new place, where he decided to catch a little nap. But as soon as he lay down he felt antsy, and he soon got up and peeled the plastic top off his can of deluxe nuts. He popped two pecans, a walnut, two almonds, and a really big nut—a Brazil nut—into his mouth. But instead of starting to chew, he slipped down the stirring stick and out of the crate with the nuts in his cheeks. He surveyed the whole pier building and made his way over to the pile of wooden pallets. Some of the ratlings were playing near the steel drum. When none of them were looking his way, he crept under the bottom pallet and hid the nuts in a dark corner.

Soon he was back stuffing his cheeks with more nuts. He didn’t even know why he wanted to hide them—though earlier, when Walter commented that it was almost noon, he had noticed that the sun was a bit off to the south, not directly overhead. Something told him that with fall coming he had to squirrel away food for the winter. Of course, he’d never experienced a fall or a winter, and it would have been far more convenient, and probably safer, to leave the nuts in the can. But that didn’t keep him from spending the rest of the afternoon caching nuts in every conceivable nook, high or low, in the pier. He couldn’t help himself.

He was hiding the last batch just as Lucy was carrying the meager pile of rejected reading material to the fuel pile, so he helped her and Beckett lug the rest over to their new place. Once they’d arranged Beckett’s periodicals, Lucy suggested they all go to the roof to watch the sunset.

“You two go,” Beckett said. “I need to read up on mayoring.”

Even if Beckett had had a book or article on the subject, it was doubtful there was enough light left for him to read by, but he had a feeling they might prefer to watch the sunset by themselves. So Lucy and Phoenix tiptoed downstairs past Mrs. P., who was dozing with a smile on her snout, and out the door. Phoenix zipped up to the top of Mrs. P.’s former home and watched, impressed, as Lucy climbed up after him. But just as he was thinking she must have a little squirrel in her, she misjudged a crack between two slats in the second highest crate and slipped. She landed on a narrow ledge below and tumbled off it, bouncing all the way down and ending up flat on her back on the ground. A mother and two ratlings hustled over to see if she was all right, only just beating Phoenix, who got down the stack of crates faster than he’d ever climbed down anything. But before any of them could even offer Lucy a paw, she was getting up, laughing at herself.

“What a klutz!” she said.

“Are you really okay?” asked the mother rat. “That was quite a fall.”

Lucy dusted herself off. “I’m fine, thanks. But how embarrassing!”

“It’s steep,” Phoenix said, cocking an eye back up the stack.

“Do you always climb down backward like that, Mr. Phoenix?” asked the bigger ratling.

Phoenix froze. He’d been so worried about Lucy, he hadn’t even thought about his manner of descent. But Lucy’s way of laughing at herself must have been contagious, for he suddenly burst out laughing himself.

“I’m afraid I do,” he said. “I guess I’ve never been much of a tree squirrel.”

“Unless I’m mistaken, you climbed up that substation twice,” said the mother rat. “Now that took pluck. Nobody cares a straw how you climb down.”

Both ratlings bobbed their heads in agreement. Lucy grinned and spanked the dust off her paws.

“This time I’ll try not to make a fool of myself,” she said, and she started up the crates again.

“Better stay right behind her, Mr. Phoenix,” the bigger ratling whispered, “so you can catch her.”

Phoenix did, but Lucy didn’t need any catching. She made it onto the top of Mrs. P.’s old crate without another misstep. Not even pausing to catch her breath, she scampered up the yardstick. Phoenix dashed up right behind her.

Side by side on the pier’s roof, the two of them took in the sunset. There wasn’t a bird of prey in sight, though they heard the occasional squawk of a seagull and the whooshing sound of passing traffic helicopters. They also heard the gleeful cries of Junior and the rest, still at it down on the half-sunken dock. Farther out, the river was unusually tranquil, the silky water catching the sky’s ambers and pinks. For a while neither of them spoke, but when the pinks began to turn to purple, Lucy said, “I bet I know what you’re thinking about.”

“What?” Phoenix asked.

“That pretty little squirrel by the pond where you’re from.”

“Actually, I was thinking how pretty this view is.”

“But Phoenix, you’ve been high up in trees. And to the top of the substation. You’ve even flown with hawks. This must seem like nothing to you.”

He had, he realized, seen some spectacular views, starting with that first time he slipped out of the nest and climbed to the top of his parents’ pine. But when she asked what the most beautiful view was he’d ever seen, he didn’t have to think long.

“This,” he said.

“Really?” she said, wide-eyed. “Why?”

“I guess . . . it must be the time of day.”

It was a magical time of day. But again he may have been fudging a bit, for the best views are always the ones you share with someone—though just then he probably would have found a storm sewer beautiful. The river was almost as calm as the pond where he’d been snatched, so he could imagine looking off the end of the pier and seeing himself in the water, but with the pier safe and his downward climbing no longer weighing on him, not even the thought of his reflection could darken his mood.

“It must be the time of day” seemed to satisfy Lucy, however, for she inched sideways until, mangy as he was, they were actually touching. Then her stomach growled.

“I’m so sorry!” she cried, mortified.

“Are you hungry?” he asked.

“Well, a little, I guess,” she admitted.

Phoenix went off to a corner of the roof, lifted up a piece of loose tarpaper, and pulled out a nut. He’d stashed three up here earlier but took only one back to Lucy. It was pale and round.

“I thought we ate all these!” she exclaimed.

“I found this last one in the bottom of the can.”

“Why’d you bring it up here?”

“It’s a squirrel thing,” he said with a shrug.

Smiling, she insisted they split the nut, so he stuck it between his impressive front teeth, bit down very gently, and spat out two perfect halves. When he handed her one, she held it up.

“To home,” she said, and she popped the half nut into her mouth, not minding in the least that it had been in his.

Phoenix echoed the sentiment, tapping the roof with his furless tail as he savored the snack.