1

coffee

Arabian Origins

The earliest employment of [coffee and tea] is veiled in as deep a mystery as that which surrounds the chocolate plant One can only say that…they have all been used from time immemorial, and that all three are welcome gifts from a rude state of civilization to the highest which exists today. By the savages and the Aztecs of America, by the roving tribes of Arabia, and by the dwellers in the farther East, the virtues of these three plants were recognized long before any one of them was introduced into Europe.

—William Baker, The Chocolate Plant and Its Products, 1891

With every cup of coffee you drink, you partake of one of the great mysteries of cultural history. Despite the fact that the coffee bush grows wild in highlands through-out Africa, from Madagascar to Sierra Leone, from the Congo to the mountains of Ethiopia, and may also be indigenous to Arabia, there is no credible evidence coffee was known or used by anyone in the ancient Greek, Roman, Middle Eastern, or African worlds.1 Although European and Arab historians repeat legendary African accounts or cite lost written references from as early as the sixth century, surviving documents can incontrovertibly establish coffee drinking or knowledge of the coffee tree no earlier than the middle of the fifteenth century in the Sufi monasteries of the Yemen in southern Arabia.2

The myth of Kaldi the Ethiopian goatherd and his dancing goats, the coffee origin story most frequently encountered in Western literature, embellishes the credible tradition that the Sufi encounter with coffee occurred in Ethiopia, which lies just across the narrow passage of the Red Sea from Arabia’s western coast. Antoine Faustus Nairon, a Maronite who became a Roman professor of Oriental languages and author of one of the first printed treatises devoted to coffee, De Saluberrimá Cahue seu Café nuncupata Discurscus (1671), relates that Kaldi, noticing the energizing effects when his flock nibbled on the bright red berries of a certain glossy green bush with fragrant blossoms, chewed on the fruit himself. His exhilaration prompted him to bring the berries to an Islamic holy man in a nearby monastery. But the holy man disapproved of their use and threw them into the fire, from which an enticing aroma billowed. The roasted beans were quickly raked from the embers, ground up, and dissolved in hot water, yielding the world’s first cup of coffee. Unfortunately for those who would otherwise have felt inclined to believe that Kaldi is a mythopoeic emblem of some actual person, this tale does not appear in any earlier Arab sources and must therefore be supposed to have originated in Nairon’s caffeine-charged literary imagination and spread because of its appeal to the earliest European coffee bibbers.

Another origin story, attributed to Arabian tradition by the missionary Reverend Doctor J.Lewis Krapf, in his Travels, Researches and Missionary Labors During Eighteen Years Residence in Eastern Africa (1856), also ascribes to African animals an essential part in the early progress of coffee. The tale enigmatically relates that the civet cat carried the seeds of the wild coffee plant from central Africa to the remote Ethiopian mountains. There the plant was first cultivated, in Arusi and Ilta-Gallas, home of the Galla warriors. Finally, an Arab merchant brought the plant to Arabia, where it flourished and became known to the world.3 The so-called cat to which Krapf refers is actually a cat-faced relative of the mongoose. By adducing its role in propagating coffee, Krapf’s tale was undoubtedly referencing the civet cat’s predilection for climbing coffee trees and pilfering and eating the best coffee cherries, as a result of which the undigested seeds are spread by means of its droppings. (For a modern update of this story, see the discussion of Kopi Luak, chapter 12.)

Both stories, of prancing goats and wandering cats, reflect the reasonable supposition that Ethiopians, the ancestors of today’s Galla tribe, the legendary raiders of the remote Ethiopian massif, were the first to have recognized the energizing effect of the coffee plant. According to this theory, which takes its support from traditional tales and current practice, the Galla, in a remote, unchronicled past, gathered the ripe cherries from wild trees, ground them with stone mortars, and mixed the mashed seeds and pulp with animal fat, forming small balls that they carried for sustenance on war parties. The flesh of the fruit is rich in caffeine, sugar, and fat and is about 15 percent protein. With this preparation the Galla warriors devised a more compact solution to the problems of hunger and exhaustion than did the armies of World Wars I and II, who carried caffeine in the form of tablets, along with chocolate bars and dried foodstuffs.

James Bruce of Kinnarid, F.R.S. (1730–94), Scottish wine merchant, consul to Algiers and the first modern scientific explorer of Africa, left Cairo in 1768 via the Red Sea and traveled to Ethiopia. There he observed and recorded in his book, Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile (1790), the persistence of what are thought to have been these ancient Gallæn uses of coffee:

The Gallæ is a wandering nation of Africa, who, in their incursions into Abyssinia, are obliged to traverse immense deserts, and being desirous of falling on the towns and villages of that country without warning, carry nothing to eat with them but the berries of the Coffee tree roasted and pulverized, which they mix with grease to a certain consistency that will permit of its being rolled into masses about the size of billiard balls and then put in leathern bags until required for use. One of these balls, they claim will support them for a whole day, when on a marauding incursion or in active war, better than a loaf of bread or a meal of meat, because it cheers their spirits as well as feeds them.4

Other tribes of northeastern Africa are said to have cooked the berries as a porridge or drunk a wine fermented from the fruit and skin and mixed with cold water. But, despite such credible inferences about its African past, no direct evidence has ever been found revealing exactly where in Africa coffee grew or who among the natives might have used it as a stimulant or even known about it there earlier than the seventeenth century.

Yet even without the guidance of early records, we can judge from the plant’s prevalence across Africa in recent centuries that coffee was growing wild or under cultivation throughout that continent and possibly other places during the building of the Pyramids, the waging of the Trojan War, the ascendancy of Periclean Athens, and the conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great, and that it continued to flower, still largely unknown, through the rise and fall of the Roman Empire and the early Middle Ages.

If this is so, then why was coffee’s descent from the Ethiopian massif and entry into the wide world so long delayed? It is true that some of the central African regions in which coffee probably grew in the remote past remained impenetrable until the nineteenth century, and their inhabitants had little or no contact with men of other continents. But the Ethiopian region itself has been known to the Middle East and Europe alike for more than three thousand years. Abyssinia, roughly coextensive with Ethiopia today, long enjoyed extensive trading, cultural, political, and religious interactions with the more cosmopolitan empires that surrounded it. Abyssinia was a source of spices for Egypt from as early as 1500 B.C. and continues as a source today. The Athenians of Periclean Athens knew the Abyssinian tribes by name. Early Arabian settlers came from across the narrow Red Sea and founded colonies in Abyssinia’s coastal regions. It is inescapable that this area, although far from being a political and social hub, was known to outsiders throughout history. The discovery of coffee, therefore, is one that ancient or medieval European or Middle Eastern traders, soldiers, evangelists, or travelers should have been expected to have made very early, here, if nowhere else. The fact remains that, for some unknown reason, they did not.5

Coffee as Materia Medica: The First Written References

There is evidence that the coffee plant and the coffee bean’s action as a stimulant were known in Arabia by the time of the great Islamic physician and astronomer Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya El Razi (852–932), called “Rhazes,” whose work may offer the first written mention of them. The merit of this attribution depends on the meaning, in Rhazes’ time, of the Arabic words “bunn” and “buncham.” Across the sea in Abyssinia these words referred, respectively, to the coffee berry and the drink, and they still have these meanings there today. In his lost medical textbook, Al-Haiwi (The Continent), Rhazes describes the nature and effects of a plant named “bunn” and a beverage named “buncham” and what he says about the beverage’s effects is at least consistent with a reference to coffee in terms of humoral theory: “Bunchum is hot and dry and very good for the stomach.”6

However, the oldest extant document referring to buncham is the monumental classic discourse The Canon of Medicine (Al-Ganum fit-Tebb), written by Avicenna (980–1037) at the turn of the eleventh century. The fifth and final part of his book is a pharmacopoeia, a manual for compounding and preparing medicines, listing more than 760 drugs,7 which includes an entry for buncham. In the Latin translation made in the twelfth century, this entry reads in part, “Bunchum quid est? Est res delatade Iamen. Quidam autem dixerunt, quod est ex radicibus anigailen…Bunchum, what is that? It comes from Yemen. Some say it derives from the roots of anigailen…]”8 In explaining the medicinal properties and uses of bunn and buncham, Avicenna uses these words in apparently the same way as Rhazes (the unroasted beans are yellow):

As to the choice thereof, that of a lemon color, light, and of a good smell, is the best; the white and the heavy is naught. It is hot and dry in the first degree, and, according to others, cold in the first degree. It fortifies the members, cleans the skin, and dries up the humidities that are under it, and gives an excellent smell to all the body.9

The name “Avicenna” is the Latinized form of the Arabic Ibn Sina, a shortened version of Abu Ali al-Husain Ibn Abdollah Ibn Sina. He was born in the province of Bokhara, and when only seventeen years old he cured his sultan of a long illness and was, in compensation, given access to the extensive royal library and a position at court.10 Avicenna himself is credited with writing more than a hundred books. Some of his admirers claim, perhaps too expansively, that modern medical practice is a continuation of his system, which framed medicine as a body of knowledge that should be clearly separated from religious dogma and be based entirely on observation and analysis.11

Leonhard Rauwolf (d. 1596), a German physician, botanist, and traveler and the first European to write a description of coffee, which he saw prepared by the Turks in Aleppo in 1573, was familiar with these Islamic medical references:

In this same water they take a fruit called Bunn, which in its bigness, shape and color is almost like unto a bayberry with two thin shells surrounded, as they inform me, are brought from the Indies; but as these in themselves are, and have within them, two yellowish grains in two distinct cells, being they agree in their virtue, figure, looks, and name with the Buncham of Avicenna and the Bunca of Rasis ad Almans exactly; therefore I take them to be the same.12

It was no accident that Rauwolf and other early European writers on coffee should have been acquainted with Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine, which, following its translation into Latin in the twelfth century by Italian orientalist Gerard Cremonensis (1114–87), became the most respected book in Europe on the theory and practice of medicine. Few books in history have been as widely distributed or as important in the lives and fortunes of so many people around the world.13 The Canon was required reading at the university of Leipzig until 1480 and that of Vienna until nearly 1600. At Montpellier, France, a major center of medical studies, where Dr. Daniel Duncan was to write Wholesome Advise against the Abuse of Hot Liquors, Particularly of Coffee, Chocolate, Tea (1706), it remained a principal basis of the curriculum until 1650.14

The fact that the Canon apparently mentions the coffee plant and the coffee beverage, describing them in the same humoral terms used by later physicians and ascribing to them several of the actions of the drug we now know is caffeine, makes the stunning silence about coffee in the Middle East and Europe, from Avicenna, in the year A.D. 1000, until the Arab scholars of the 1500s, the more puzzling. This accessible, apparently safe plant with stimulating and refreshing properties was destined to become an item of great interest in Islam, whose believers were not permitted to drink alcohol. It was equally well received in Christian Europe, where water was generally unsafe and where the drink served at breakfast, luncheon, and dinner was beer. Once people from each of these two cultures had had a good taste of coffee, history proves that the drink made its way like a juggernaut, mowing down entrenched customs and opposing interests in its path. Yet, after the time of Avicenna, coffee was apparently forgotten in the Islamic world for more than five hundred years.

One way to gain an appreciation of the mystery of coffee’s late appearance is to note that, even if the Rhazian reference is deemed genuine, coffee remained unknown to the Arabs until after Arab traders had become familiar with Chinese tea. Arab knowledge of tea as an important commodity is demonstrated by an Arabian traveler’s report in A.D. 879 that the primary sources of tax revenue in Canton were levies on tea and salt. Awareness of tea’s use as a popular tonic is evinced in the words of Suleiman the Magnificent (1494–1566): “The people of China are accustomed to use as a beverage an infusion of a plant, which they call sakh…. It is considered very wholesome. This plant is sold in all the cities of the Empire.”15 Considering that tea was produced in a land half a world away, accessible only by long, daunting sea journeys or even more hazardous extended overland routes, the lack of Arab familiarity with coffee, which grew wild just across narrow passage of the Red Sea, becomes even harder to understand.

The Coffee Drinkers That Never Were: Fabulous Ancient References to Coffee

Of course, if we were to find that the ancients had known about and used coffee, this lacuna would be filled in and the perplexity resolved.

Some imaginative chroniclers in modern times, uncomfortable with the possibility that their age should know of something so important that had been unknown to the ancient wise, have satisfied themselves that coffee was in fact mentioned in the earliest writings of the Greek and Hebrew cultures. These supposed ancient references, though exhibiting great variety, have one common element that mirrors the understanding of coffee at the time they were asserted: They present it primarily as a drug and measure its significance in terms of its curative or mood-altering powers.

Pietro della Valle, an Italian who from 1614 to 1626 toured Turkey, Egypt, Eritrea, Palestine, Persia, and India, advanced in his letters, published as Viaggi in Turchia, Persia ed India descritti da lui medesimo in 54 lettere famigliari, the implausible theory that the drink nepenthe, prepared by Helen in the Odyssey, was nothing other than coffee mixed with wine. In the fourth book of the epic, in which Telemachus, Menelaus, and Helen are eating dinner, the company becomes suddenly depressed over the absence of Odysseus. Homer tells us:

Then Jove’s daughter Helen bethought her of another matter. She drugged the wine with an herb that banishes all care, sorrow, and ill humour. Whoever drinks wine thus drugged cannot shed a single tear all the rest of the day, not even though his father and mother both of them drop down dead, or he sees a brother or a son hewn in pieces before his very eyes. This drug, of such sovereign power and virtue, had been given Helen by Polydamna wife of Thon, woman of Egypt, where there grow all sorts of herbs, some good to put into the mixing bowl and others poisonous. Moreover, every one in the whole country is a skilled physician, for they are of the race of Pæeon. When Helen had put this drug in the bowl,…[she] told the servants to serve the wine round.16

These wondrous effects sound more like those of heroin mixed with cocaine than of coffee mixed with wine. The word “nepenthes,” meaning “no pain” or “no care” in Greek, is used in the original text to modify the word “pharmakos,” meaning “medicine” or “drug.”17 For at least the last several hundred years, “nepenthe” has been a generic term in medical literature for a sedative or the plant that supplies it; as such, it hardly fits the pharmacological profile of either caffeine or coffee. Nevertheless, the pioneering Enlightenment scholars Diderot and d’Alembert repeated Pietro della Valle’s idea in their Encyclopédie (much of which was drafted in daily visits to one of Paris’s earliest coffee houses). The fact that Homer tells us that the use of nepenthe was learned in Egypt, which can be construed to include parts of Ethiopia, together with the undoubted capacity of coffee to drive away gloom and its reputation for making it impossible to shed tears, may have helped to make this identification more appealing.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it became fashionable for European scholars to continue, as della Valle had begun, in theorizing about the knowledge the ancients had had of modern drugs. Not everyone, of course, was convinced. Dr. Simon André Tissot, a Swiss medical writer working in 1769, acknowledges the value of coffee as stimulant to the wit, but warns that we should neither underestimate its dangers nor exaggerate its value: for “we have to ask ourselves whether Homer, Thucydides, Plato, Lucretius, Virgil, Ovid, and Horace, whose works will be a joy for all time, ever drank coffee.”18 Many others, however, followed an imaginary trail of coffee beans leading back to ancient Greece. Sir Henry Blount (1602– 82), a Puritan teetotaler frequently dubbed the “father of the English coffeehouse,” traveled widely in the Levant, where he drank coffee with the Sultan Murat IV. On his return to England, he became one of the earliest boosters of the “Turkish renegade,” as coffee was sometimes called. He brewed a controversy when he repeated a gratuitous claim that the exotic beverage he had enjoyed in the capitals of the Near East was in fact the same as a famous drink of the ancient Spartans:

They have another drink not good at meat, called Cauphe, made of a Berry as big as a small Bean, dried in a Furnace and beat to Pouder, of a Soot-colour, in taste a little bitterish, that they seeth and drink as hot as may be endured: It is good all hours of the day, but especially morning and evening, when to that purpose, they entertain themselves two or three hours in Cauphe-houses, which in all Turkey abound more than Inns and Ale-houses with us; it is thought to be the old black broth used so much by the Lacedaemonians [Spartans], and dryeth ill Humours in the stomach, and the Brain, never causeth Drunkenness or any other Surfeit, and is a harmless entertainment of good Fellowship; for thereupon Scaffolds half a yard high, and covered with Mats, they sit Cross-leg’d after the Turkish manner, many times two or three hundred together, talking, and likely with some poor musick passing up and down.19

Blount’s howler was passed along by Robert Burton (1577–1640), an Elizabethan divine, George Sandys (1578–1644), an Anglo-American poet and traveler, and James Howell (1595–1666), the first official royal historian of England, and with this pedigree entered the arcana of coffee folklore. Putting the Sparta story aside, we should notice Blount’s evocative account of the Turks in their preparatory customs and convivial consumption of the black brew. The social scene Blount sets is almost eerily similar to coffeehouse ambiance in most parts of the world today.

Perhaps even more far-fetched than the putative Spartan coffee were the efforts to discover coffee stories in the Old Testament. George Paschius, in his Latin treatise New Discoveries Made Since the Time of the Ancients (Leipzig, 1700), wrote that coffee was one of the gifts given David by Abigail to mollify his anger with Nabal (I Samuel 25:18), even though the “five measures of parched grain” mentioned were clearly wheat, not coffee beans. Swiss minister, publicist, and political writer Pierre Etienne Louis Dumont (1759–1829) fancied that other biblical references to coffee included its identification with the “red pottage” for which Esau sold his birthright (Genesis 25:30) and with the parched grain that Boaz ordered be given to Ruth.20

Because in the Middle Eastern world, no less than the European, caffeine-bearing drinks have invariably been regarded as drugs before they were accepted as beverages, it is not surprising that a number of early Islamic legends celebrate coffee’s miraculous medicinal powers and provide coffee drinking with ancient and exalted origins. The seventeenth-century Arab writer Abu al-Tayyib al-Ghazzi relates how Solomon encountered a village afflicted with a plague for which the inhabitants had no cure. The angel Gabriel directed him to roast Yemeni coffee beans, from which he brewed a beverage that restored the sick to health. According to other Arab accounts, Gabriel remained busy behind the heavenly coffee bar until at least the seventh century; a popular story relates how Mohammed the Prophet, in this tradition supposed to have been stricken with narcolepsy, was relieved of his morbid somnolence when the angel served him a hot cup infused from potent Yemeni beans. Another related Islamic story, repeated by Sir Thomas Herbert, who visited Persia in 1626, held that coffee was “brought to earth by the Angel Gabriel in order to revive Mohammed’s flagging energies. Mohammed himself was suppose to have declared that, when he had drunk this magic potion, he felt strong enough to unhorse forty men and to posses forty women.”21 Al-Ghazzi, whose tales place the first appearance of coffee in biblical times—and who was aware that his grandparents had never heard of the drink—explains that the ancient knowledge of coffee was subsequently lost until the rediscovery of coffee as a beverage in the sixteenth century.

In other Islamic folk accounts, which may have some factual basis, a man named “Sheik Omar” is given credit for being the first Arab to discover the bean and prepare coffee. D’Ohsson, a French historian, basing his claims on Arab sources, writes that Omar, a priest and physician, was exiled, with his followers, from Mocha into the surrounding wilderness of Ousab in 1258 for some moral failing. Facing starvation, and finding nothing to eat except wild coffee berries, the exiles boiled them and drank the resulting brew. Omar then gave the drink to his patients, some of whom had followed him to Ousab for treatment. These patients carried word of the magical curative properties of coffee back to Mocha, and, in consequence, Omar was invited to return. A monastery was built for him, and he was acknowledged as patron saint of the city, achieving this honor as father of the habit that soon became the economic lifeblood of the region. In another version of this tale, Omar was led by the spirit of his departed holy master to the port of Mocha, where he became a holy recluse, living beside a spring surrounded by bright green bushes. The berries from the bushes sustained him, and he used them to cure the townspeople of plague. Thus coffee and caffeine established his reputation as a great sage, healer, and holy man.22

Coffee to Coffeehouses: Marqaha and the Slippery Slope

‘Abd Al-Qadir al-Jaziri (fl. 1558) wrote the earliest history of coffee that survives to this day. As unconvinced by the Omar stories as modern scholars are, he provided several alternative accounts of coffee’s inception in Arabia, of which the first, and probably most reliable, is based on the lost work of the true originator of literature on coffee, Shihab Al-Din Ibn ‘Abd al- Ghaffar (fl. 1530). According to Jaziri, ‘Abd al-Ghaffar explained that at the beginning of the sixteenth century, while living in Egypt, he first heard of a drink called “qahwa” that was becoming popular in the Yemen and was being used by Sufis and others to help them stay awake during their prayers. After inquiring into the matter, ‘Abd al-Ghaffar credited the introduction and promotion of coffee to “the efforts of the learned shaykh, immam, mufti, and Sufi Jamal al-Din Abu ‘Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Sa’id, known as Dhabhani.”23

The venerable Dhabhani (d. 1470)24 had been compelled by unknown circumstances to leave Aden and go to Ethiopia, where, among the Arab settlers

he found the people using qahwa, though he knew nothing of its characteristics. After he had returned to Aden, he fell ill, and remembering [qahwa], he drank it and benefited by it. He found that among its properties was that it drove away fatigue and lethargy, and brought to the body a certain sprightliness and vigor. In consequence… he and other Sufis in Aden began to use the beverage made from it, as we have said. Then the whole people—the learned and the common— followed [his example] in drinking it, seeking help in study and other vocations and crafts, so that it continued to spread.

A generation after ‘Abd al-Ghaffar, Jaziri conducted his own investigation, writing to a famous jurist in Zabid, a town in the Yemen, to inquire how coffee first came there. In reply, his correspondent quoted the account of his uncle, a man over ninety, who had told him:

“I was at the town of Aden, and there came to us some poor Sufi, who was making and drinking coffee, and who made it as well for the learned jurist Muhammad Ba-Fadl al-Halrami, the highest jurist at the port of Aden, and for… Muhammad al-Dhabhani. These two drank it with a company of people, for whom their example was sufficient.”

Jaziri concludes that it is possible that ‘Abd al-Ghaffar was correct in stating that Dhabhani introduced coffee to Aden, but that it is also possible, as his correspondent claimed, that some other Sufi introduced it and Dhabhani was responsible only for its “emergence and spread.” ‘Abd Al-Ghaffar and Jaziri are in accord that it was as a stimulant, not a comestible, that coffee was used from the time of its earliest documented appearance in the world. More than this we may never discover. For the astonishing fact is that, although all the Arab historians are in accord that the story of coffee drinking as we know it apparently begins somewhere in or around the Yemen in a Sufi order in the middle of the fifteenth century, additional details of its origin had already been mislaid or garbled within the lifetimes of people who could remember when coffee had been unknown.

In any case, the spread of coffee from Sufi devotional use into secular consumption was a natural one. Though the members of the Sufi orders were ecstatic devotees, most were of the laity, and their nightlong sessions were attended by men from many trades and occupations. Before beginning the dhikr, or ritual remembrance of the glory of God, coffee was shared by Sufis in a ceremony described by Jaziri Avion: “They drank it every Monday and Friday eve, putting it in a large vessel made of red clay. Their leader ladled it out with a small dipper and gave it to them to drink, passing it to the right, while they recited one of their usual formulas, ‘There is no God, but God, the Master, the Clear Reality.’” 25 When morning came, they returned to their homes and their work, bringing the memory of caffeine’s energizing effects with them and sharing the knowledge of coffee drinking with their fellows. Thus, from the example of Sufi conclaves, the coffeehouse was born. As coffeehouses, or kahwe khaneh, proliferated, they served as forums for extending coffee use beyond the circle of Sufi devotions. By 1510 coffee had spread from the monastaries of the Yemen into general use in Islamic capitals such as Cairo and Mecca, and the consumption of caffeine had permeated every stratum of lay society.

Although destined for remarkable success in the Islamic world, coffee and coffee-houses met fierce opposition there from the beginning and continued to do so. Even though the leaders of some Sufi sects promoted the energizing effects of caffeine, many orthodox Muslim jurists believed that authority could be found in the Koran that coffee, because of these stimulating properties, should be banned along with other intoxicants, such as wine and hashish, and that, in any case, the new coffeehouses constituted a threat to social and political stability.26 Considering that coffee was consumed chiefly for what we now know are caffeine’s effects on human physiology, especially the marqaha, the euphoria or high that it produces, it is easy to understand the reasons such scruples arose.27

Perhaps no single episode illustrates the players and issues involved in these controversies better than the story of Kha’ir Beg, Mecca’s chief of police, who, in accord with the indignation of the ultra-pious, instituted the first ban on coffee in the first year of his appointment by Kansuh al-Ghawri, the sultan of Cairo, 1511. Kha’ir Beg was a man in the timeless mold of the reactionary, prudish martinet, reminiscent of Pentheus in Eurypides’ Bacchoe,28 someone who was not only too uptight to have fun but was alarmed by evidence that other people were doing so. Like Pentheus, he was the butt of satirical humor and mockery, and nowhere more frequently than in the coffeehouses of the city.

Beg, as the enforcer of order, saw in the rough and ready coffeehouse, in which people of many persuasions met and engaged in heated social, political, and religious arguments, the seeds of vice and sedition, and, in the drink itself, a danger to health and well-being. To end this threat to public welfare and the dignity of his office, Beg convened an assembly of jurists from different schools of Islam. Over the heated objections of the mufti of Aden, who undertook a spirited defense of coffee, the unfavorable pronouncements of two well-known Persian physicians, called at Beg’s behest, and the testimony of a number of coffee drinkers about its intoxicating and dangerous effects ultimately decided the issue as Beg had intended.29 Beg sent a copy of the court’s expeditious ruling to his superior, the sultan of Cairo, and summarily issued an edict banning coffee’s sale. The coffeehouses in Mecca were ordered closed, and any coffee discovered there or in storage bins was to be confiscated and burned. Although the ban was vigorously enforced, many people sided with the mufti and against the ruling of Beg’s court, while others perhaps cared more for coffee than for sharia, the tenants of the holy law, for coffee drinking continued surreptitiously.

To the rescue of caffeine users came the sultan of Cairo, Beg’s royal master, who may well have been in the middle of a cup of coffee himself, one prepared by his battaghis, the coffee slaves of the seraglio, when the Meccan messenger delivered Beg’s pronouncement. The sultan immediately ordered the edict softened. After all, coffee was legal in Cairo, where it was a major item of speculation and was, according to some reports, even used as tender in the marketplaces. Besides, the best physicians in the Arab world and the leading religious authorities, many of whom lived in Cairo at the time, approved of its use. So who was Kha’ir Beg to overturn the coffee service and spoil the party? When in the next year Kha’ir Beg was replaced by a successor who was not averse to coffee, its proponents were again able to enjoy the beverage in Mecca without fear. There is no record of whether the sultan of Cairo repented of his decision when, ten years later, in 1521, riotous brawling became a regular occurrence among caffeine-besotted coffeehouse tipplers and between them and the people they annoyed and kept awake with their late-night commotion.

In 1555, coffee and the coffeehouse were brought to Constantinople by Hakam and Shams, Syrian businessmen from Aleppo and Damascus, respectively, who made a fortune by being the first to cash in on what would become an unending Ottoman love affair with both the beverage and the institution.30 In the middle of the sixteenth century, coffeehouses sprang up in every major city in Islam, so that, as the French nineteenth-century historian Mouradgea D’Ohsson reports in his seven-volume history of the Ottoman Empire, by 1570, in the reign of Selim II, there were more than six hundred of them in Constantinople, large and small, “the way we have taverns.” By 1573, the German physician Rauwolf, quoted above as the first to mention coffee in Europe, reported that he found the entire population of Aleppo sitting in circles sipping it. Coffee was in such general use that he believed those who told him that it had been enjoyed there for hundreds of years.31

As a result of the efforts of Hakam and Shams and other entrepreneurs, Turks of all stations frequented growing numbers of coffeehouses in every major city, many small towns, and at inns on roads well trafficked by travelers. One contemporary observer in Constantinople noted “[t]he coffeehouses being thronged night and day, the poorer classes actually begging money in the streets for the sole object of purchasing coffee.”32 Coffee was sold in three types of establishments: stalls, shops, and houses. Coffee stalls were tiny booths offering take-out service, usually located in the business district. Typically, merchants would send runners to pick up their orders. Coffee shops, common in Egypt, Syria, and Turkey, were neighborhood fixtures, combining take-out and a small sitting area, frequently outdoors, for conversationalists. Coffeehouses were the top-of- the-line establishments, located in exclusive neighborhoods of larger cities and offering posh appointments, instrumentalists, singers, and dancers, often in gardenlike surroundings with fountains and tree-shaded tables. As these coffeehouses increased in popularity, they became more opulent. To these so-called schools of the wise flocked young men pursuing careers in law, ambitious civil servants, officers of the seraglio, scholars, and wealthy merchants and travelers from all parts of the known world. All three—shop, stall, and house—were and remain common in the Arab world, as they are in the West today.

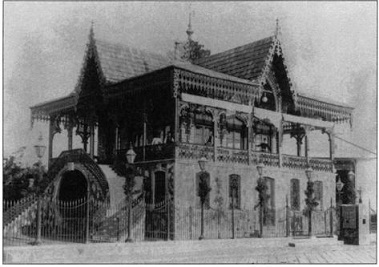

Photograph of Café Eden, Smyrna, from an albumen photograph by Sebah and Joaillier (active 1888-c. 1900). The sign in the foreground reads “Jardin de L’Eden.” This café is typical of top-of-the-line establishments located in the better neighborhoods of the larger cities throughout the Levant. (Photograph by Sebah and Joaillier, University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia, negative #s4–142210)

But the debates over the propriety of coffee use did not end with Beg’s tenure or the proliferation of the coffeehouse. Two interpretive principles continued to vie throughout these debates. On the one side was the doctrine of original permissibility, according to which everything created by Allah was presumed good and fit for human use unless it was specifically prohibited by the Koran. On the other was the mandate to defend the law by erecting a seyag, or “fence” around the Koran, that is, broadly construing prohibitions in order to preclude even a small chance of transgression.

The opponents of coffee drinking continued to assert their disapproval of the new habit and the disquieting social activity it seemed to engender. Cairo experienced a violent commotion in 1523, described by Walsh in his book Coffee: Its History, Classification, and Description (1894):

In 1523 the chief priest in Cairo, Abdallah Ibrahim, who denounced its use in a sermon delivered in the mosque in Hassanaine, a violent commotion being produced among the populous. The opposing factions came to blows over its use. The governor, Sheikh Obelek [El-belet], a man wise in his generation and time, then assembled the mullahs, doctors, and others of the opponents of coffee-drinking at his residence, and after listening patiently to their tedious harangues against its use, treated them all to a cup of coffee each, first setting the example by drinking one himself. Then dismissing them, courteously withdrew from their presence without uttering a single word. By this prudent conduct the public peace was soon restored, and coffee was ever afterward allowed to be used in Cairo.33

A covenant was even introduced to the marriage contract in Cairo, stipulating that the husband must provide his wife with an adequate supply of coffee; failing to do so could be joined with other grounds as a basis for filing a suit of divorce.34 This provision shows that, even though banned from the coffeehouses, women were permitted to enjoy coffee at home.

Around 1570, by which time the use of coffee seemed well entrenched, some imams and dervishes complained loudly against it again, claiming, as Alexander Dumas wrote in his Dictionnaire de Cuisine,35 that the taste for the drink went so far in Constantinople that the mosques stood empty, while people flocked in increasing numbers to fill the coffeehouses. Once again the debate revived. In a curious reversal of the doctrine of original permissibility, some coffee opponents claimed that simply because coffee was not mentioned in the Koran, it must be regarded as forbidden. As a result coffee was again banned. However, coffee drinking continued in secret as a practice winked at by civil authorities, resulting in the proliferation of establishments reminiscent of American speakeasies of the 1920s.

Murat III, sultan of Constantinople, murdered his entire family in order to clear his way to the throne, but drew the line at allowing his subjects to debauch in the coffeehouses, and with good reason. It seems that his bloody accession was being loudly discussed there in unflattering terms, insidiously brewing sedition. In about 1580, declaring coffee “mekreet,” or “forbidden,” he ordered these dens of revolution shuttered and tortured their former proprietors. The religious sanction for his ban rested on the discovery, by one orthodox sect of dervishes, that, when roasted, coffee became a kind of coal, and anything carbonized was forbidden by Mohammed for human consumption.36 His prohibition of the coffeehouse drove the practice of coffee drinking into the home, a result which, considering his purpose of dispelling congeries of public critics, he may well have counted as a success.

During succeeding reigns, the habit again became a public one, and one that, after Murat’s successor assured the faithful that roasted coffee was not coal and had no relation to it, even provided a major source of tax revenue for Constantinople. Yet in the early seventeenth century, under the nominal rule of Murat IV (1623–40), during a war in which revolution was particularly to be feared, coffee and coffeehouses became the subject of yet another ban in the city. In an arrangement reminiscent of the intrigues of the Arabian Nights, Murat IV’s kingdom was governed in fact by his evil vizier, Mahomet Kolpili, an illiterate reactionary who saw the coffeehouses as dens of rebellion and vice. When the bastinado was unsuccessful in discouraging coffee drinking, Kolpili escalated to shuttering the coffeehouses. In 1633, noting that hardened coffee drinkers were continuing to sneak in by the posterns, he banned coffee altogether, along with tobacco and opium, for good measure, and, on the pretext of averting a fire hazard, razed the establishments where coffee had been served. As a final remedy, as part of an edict making the use of coffee, wine, or tobacco capital offenses, coffeehouse customers and proprietors were sewn up in bags and thrown in the Bosphorus, an experience calculated to discourage even the most abject caffeine addict.

Less draconian solutions to the coffeehouse threat to social stability were implemented in Persia, notably by the wife of Shah Abbas, who had observed with concern the large crowds assembling daily in the coffeehouses of Ispahan to discuss politics. She appointed mollahs, expounders of religious law, to attend the coffeehouses and entertain the customers with witty monologues on history, law, and poetry. So doing, they diverted the conversation from politics, and, as a result, disturbances were rare, and the security of the state was maintained. Other Persian rulers, deciding not to stanch the flow of seditious conversation, instead placed their spies in the coffee-houses to collect warnings of threats to the security of the regime.

The coffeehouses brought with them certain unsettling innovations in Islamic society. Even those who counted themselves among the friends of coffee drinking were not entirely comfortable with the secular public gatherings, previously unheard of in respectable society, that these places made inevitable and commonplace. The freedom to assemble in a public place for refreshment, entertainment, and conversation, which was otherwise rare in a society where everyone dined at home, created as much danger as opportunity. Before the coffeehouses opened, taverns had been the only recourse for people who wanted a night out, away from home and family, and these, in Islamic lands, where tavern keepers, like prostitutes, homosexuals, and street entertainers, were shunned by respectable people. Jaziri, when chronicling the early days of coffee in the Yemen, complained, for example, that the decorum and solemnity of the Sufi dhikr was, in the coffeehouse, displaced by the frivolity of joking and storytelling. Worse still was malicious gossip, which, when directed against blameless women, was deemed particularly odious.

From Jaziri we also learn that gaming, especially chess, backgammon, and draughts, was, in addition to idle talk, a regular feature of coffeehouse life. Card playing, reported by travelers, may have been a later introduction from Europe. However, contemporary Islamic writers, a strait-laced group to a man, disapproved of such frivolous activities, even when no money was being wagered. One of the mainstays of coffeehouse entertainment spoken of by Moslem writers was the storyteller, an inexpensive addition to the enjoyment of the patrons that was more acceptable than either gossip or gaming to the exacting moral monitors of the day.

Musical entertainments, in contrast with literary ones, though also commonplace in coffeehouses, were regarded with more disfavor. The “drums and fiddlers”37 of Mecca’s coffeehouses were mentioned by Jaziri as one of their aspects offensive to Kha’ir Beg. Evidently sharing the belief of St. Augustine that music was a sensual enjoyment that threatened to divert attention from the contemplation of God, and as such was to be regarded as a subversive force among the faithful, the Islamic moralists of the day asserted that musical entertainments deepened the debauchery into which coffeehouse patrons habitually sunk. Secular music was considered dangerous in itself, but worse for the encouragement it gave to revelry. Especially damning was the early practice, taken over from the taverns, of featuring women singers. Even when they were kept from customers’ eyes behind a screen, their voices alone were thought to offer improper sexual stimulation, which, it was often charged, led to sexual disportment with the patrons. Later accounts make it clear that these temptresses were finally banished, leaving the Islamic coffeehouses strictly to the men.

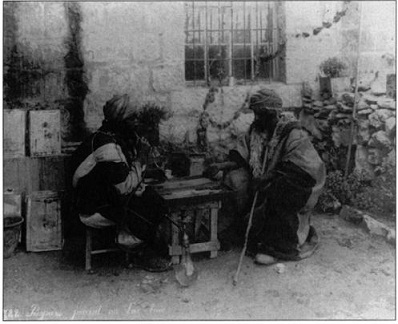

Photograph of Palestinian or Syrian peasants playing backgammon while drinking coffee and sharing a hookah pipe at a recent version of the modest Arab coffee shops that have been traditional for several hundred years, from an albumen photograph, c. 1885–1901, by Bonfils, active 1864–1916. (Photograph by Bonfils, University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia, negative #s4–142209)

Even more corrupting than women, or so these Islamic thinkers believed, was the use of hard drugs by coffeehouse denizens. Jaziri deplores the mixing of hashish, opium, and possibly other narcotic preparations with what, in his judgment, was an otherwise pure drink. He says, “Many have been led to ruin by this temptation. They can be reckoned as beasts whom the demons have so tempted.”38 Another Islamic writer of the time, Kâtib Celebi, states, “Drug addicts in particular finding [coffee] a life giving thing, which increases their pleasure, were willing to die for a cup.”39

As to the intoxicating effects of coffee itself, which we now understand are a consequence of its caffeine content, Islamic opinion was divided in bitter controversy from at least as early as ‘Abd al-Ghaffar. Some moralists likened the marqaha to inebriation with alcohol, hashish, or opium. Other writers, including an unnamed predecessor of ‘Abd al-Ghaffar, found this identification preposterous, both in degree and kind. This unresolvable dispute was of practical importance in a society in which many prominent men were coffee users and in which indulgence in any intoxicant was grounds for severe punishment. In the end, caffeine triumphed in the Islamic world, and coffee was accepted as the earthly approximation of the “purest wine, that will neither pain their heads nor take away their reason,” which the Koran teaches the blessed will enjoy in the world to come.

From the standpoint of modern secular taste, it is difficult not to find sympathetic an environment which presented the first informal, public, literary, and intellectual forum in Islam. Many of the conventions that were established in those early coffeehouses remain hallmarks of our coffeehouses today. Poets and other writers came to read their works; the air was filled with the sounds of animated colloquies on the sciences and arts; and, as in Pepys’ England and in so many other times and places, the coffeehouse became, in the absence of newspapers, a place where people gathered to learn and argue about the latest social and political events.

Because the coffeehouse is so important and coffee is so freely available today, we may be disposed to regard the Arab and Turkish attempts at prohibition as quaint and archaic. Such condescension would demonstrate an ignorance of similar efforts in later periods of history and a failure to recognize those in our own. The “caffeine temperance” movement has reasserted itself, with greater or lesser effectiveness, in almost every generation. France, Italy, and England have recurringly witnessed men who sought to enlist the power of law to enforce their own disapproval of caffeine. In the

Year of the First Coffeehouses

| City | Yearc |

| Mecca | <1500 |

| Cairo | c. 1500 |

| Constantinople | 1555 |

| Oxford | 1650 |

| London | 1652 |

| Cambridge | early 1660s |

| The Hague | 1664 |

| Amsterdam | mid-1660s |

| Marseilles | 1671 |

| Hamburg | 1679 |

| Vienna | 1683 |

| Paris | 1689 |

| Boston | 1689 |

| Leipzig | 1694 |

| New York | 1696 |

| Philadelphia | 1700 |

| Berlin | 1721 |

United States in the early twentieth century, reformers such as Harvey Washington Wiley vigorously campaigned against the use of caffeine in soft drinks. Today such groups as Caffeine Prevention Plus, who use the Internet to promote their cause, and all sorts of meddlesome do-gooders would be happy to add caffeine to the list of highly regulated or banned substances. Americans, who live with the prohibition of marijuana, heroin, and certain pharmaceuticals in general use worldwide and who are witnessing serious efforts within our government to further control or ban cigarettes, should recognize elements of their own society when hearing the story of Kha’ir Beg.

Travelers’ Tales: Visitors to the Yemen, Constantinople, Aleppo, and Cairo

There was nothing remarkable in the King’s Gardens [in Yemen], except the great pains taken to furnish it with all the kinds of trees that are common in the country; amongst which there were the coffee trees, the finest that could be had. When the deputies represented to the King how much that was contrary to the custom of the Princes of Europe (who endeavor to stock their gardens chiefly with the rarest and most uncommon plants that can be found) the King returned them this answer: That he valued himself as much upon his good taste and generosity as any Prince in Europe; the coffee tree, he told them, was indeed common in his country, but it was not the less dear to him upon that account; the perpetual verdure of it pleased him extremely; and also the thoughts of its producing a fruit which was nowhere else to be met with; and when he made a present of that that came from his own Gardens, it was a great satisfaction to him to be able to say that he had planted the trees that produced it with his own hands.40

—Jean La Roque, Voyage de L’Arabie Heureuse, 1716

Europeans, as compared with the other peoples of the world, have historically demonstrated a strong inquisitiveness about the secrets of distant nations; they have been, in short, natural tourists. It is therefore no surprise that it was from returning travelers that knowledge of the habits of the Arabs and Turks was first brought to the capitals of Italy, France, England, Portugal, Holland, and Germany.41

These European travelers throughout the Islamic domains provide many vivid accounts of early coffeehouses.42 However, as Carsten Niebuhr (1733–1815), a German biographer and traveler, comments in Travels through Arabia and Other Countries in the East (1792), many of the establishments they visited were situated in khans— combination inns, caravansaries, and warehouses—which served merchants and other travelers, and we should keep in mind that they may not have been typical of the coffeehouses catering to a residential population.

One of the earliest descriptions to reach Europe of the denizens of the coffee-houses of Constantinople was this dour assessment by Gianfrancesco Morosini, a Venetian traveler, in 1585:

All these people are quite base, of low costume and very little industry, such that, for the most part, they spend their time sunk in idleness. Thus they continually sit about, and for entertainment they are in the habit of drinking in public in shops and in the streets—a black liquid, boiling [as hot] as they can stand it, which is extracted from a seed they call Caveè… , and is said to have the property of keeping a man awake.

William Biddulph, an Elizabethan clergyman, shared Morosini’s disdain, observing that coffeehouse habitués of Aleppo were occupied exclusively with “Idle and Alehouse talke.”

Although many sipped coffee at tiny stalls or in spare public rooms, an atmosphere of luxury pervaded the grand coffeehouses, which were invariably located, according to the French coffee merchant Sylvestre Dufour, in the swankiest neighborhoods.43 Pedro Teixeira (1575–1640), a Portuguese traveler and explorer, describes one such place in Baghdad, where coffee was served in a place “built to that end”: “This house is near the river, over which it has many windows, and two galleries, making it a very pleasant resort.”44 The French traveler Jean de Thévenot (1633–67), in his Relation d’un voyage fait au Levant, a book that helped convince his countrymen to regard coffee as a comestible instead of merely as a drug, tells us that the cafés of Damascus are all “cool, refreshing and pleasant” retreats for the natives of a parched region, offering “fountains, nearby rivers, tree shaded spots, roses and other flowers.”45 Outdoor enjoyment included resting on mat-covered stone benches and enjoying the street scene.46 He certainly found more to approve in coffeehouse conviviality than did Morosini or Bidduph:

There are public coffeehouses, where the drink is prepared in very big pots for the numerous guests. At these places, guests mingle without distinction of rank or creed…

When someone is in a coffeehouse, and sees people whom he knows come in, if he is in the least ways civil, he will tell the proprietor not to take any money from them. All this is done by a single word, for when they are served with their coffee, he merely cries, “Giaba,” that is to say, “Gratis!”47

Evidently little changed over the ensuing century, for D’Ohsson confirmed the picture of coffeehouse leisure, writing, “Young idlers spend whole hours in them, smoking, playing draughts or chess and discussing affairs of the day.”

Alexander Russel, in The Natural History of Aleppo (1756), describes the coffee-house use of hashish and opium in waterpipes, and other writers, such as Edward Lane, an English Arabic scholar, in his Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (1860), also testifies to these sordid indulgences. Niebuhr, blaming the stupefied languor of the coffee imbibers on intense tobacco use, comments:

In Egypt, Syria, and Arabia, the favorite of amusement of persons in any degree above the very lowest classes, is, to spend the evening in a public coffee-house, where they hear musicians, singers, and tale-tellers, who frequent those houses in order to earn a trifle by the exercise of their respective arts. In those places of public amusement, the Orientals maintain a profound silence, and often sit whole evenings without uttering a word. They prefer conversing with their pipe; and its narcotic fumes seem very fit to allay the ferment of their boiling blood. Without recurring to a physical reason, it would be hard to account for the general relish which these people have for tobacco; by smoking, they divert the spleen and languor which hang about them, and bring themselves in a slight degree, into the same state of spirits which the opium eaters obtain from that drug. Tobacco serves them instead of strong liquors, which they are forbidden to use.48

The Reverend R.Walsh was a senior member of the British diplomatic service stationed in Constantinople in the early nineteenth century. In his book Narrative of a Journey from Constantinople to England (1828), he describes a coffeehouse he visited while staying the night at an inn, typical of the sort of establishment that had been so often visited by earlier European travelers, on his way home:

I passed a very feverish sleepless night, which I attributed to either of two causes; one, the too free use of animal food and vinous liquors, after violent exercise…. Another, and perhaps the real cause, was that we slept on the platform of a miserable little coffee-house, attached to the kahn, which was full of people smoking all night. The Turks of this class are offensively rude and familiar; they stretch themselves out and lay across us, without scruple or apology; and within a few inches of my face, was the brazier of charcoal, with which they lighted their pipes and heated their coffee. After a night passed in a suffocating hole, lying on the bare boards, inhaling tobacco smoke and charcoal vapors, and annoyed every minute by the elbows and knees of rude Turks; it was not to be wondered at, that I rose sick and weak, and felt as if I was altogether unable to proceed on my journey.”49

However, Walsh could not afford the luxury of a layover; and so, taking refreshment from an exhilarating breeze, he allowed himself to be helped onto his horse and made his way down the road.

Life among the Bedouins has always maintained a distinctive savor. W.B. Seabrook, in his book Adventures in Arabia (1927), gives a vivid account of coffee’s place in a timeless nomadic culture where lunch consisted of dried dates, bread, and fermented camel’s milk and the one cooked meal of each day was a whole carcass of a sheep or goat, served over rice and gravy:

Coffee-making is the exclusive province of the men. Its paraphernalia for a sheik’s household fills two great camel hampers. We had five pelican-beaked brass pots, of graduated sizes, up to the great grand-father of all the coffee pots, which held at least ten gallons; a heavy iron ladle, with a long handle inlaid with brass and silver, for roasting the beans; wooden mortar and pestle, elaborately carved, for pounding them; and a brass inlaid box containing the tiny cups without handles.50

Seabrook enjoyed the honor of sharing coffee with the Pasha Mitkhal, leader of the tribe, whom he describes as “a born aristocrat,” about forty, with a slender build and a small pointed black beard and mustache, who “wore no gorgeous robes nor special insignia of rank.” Except for a headcloth of finer texture and a muslin undergarment which he wore beneath his black camel hair cloak and his black headcoil of twisted horsehair, he dressed exactly as his warriors. Once Mitkhal was seated in his tent, Man-sour, his black attendant, “approached with a long-spouted brass coffee pot in his left hand, and two tiny cups without handles in the palm of his right.”51

On another occasion, Seabrook, observing a man accidentally overturn the large communal coffeepot, was surprised to hear the company exclaim, “Khair Inshallah!,” which means, “A good omen!” Mitkhal later explained that this old custom may have originated with a desire to help the klutz save face, although Seabrook speculated that it traces to pre-Moslem pagan libations in the sand.52

A less favorable prognostication, however, attends the deliberate spilling of coffee. Among the Druse, Bedouin warriors of the Djebel, Seabrook took coffee with Ali bey, the ranking patriarch, in the company of his four sons and ten solemn Druse elders. Sitting cross-legged before the charcoal fire, Ali bey honored his guests by making the coffee himself and serving it in two small cups which were passed around and around the circle, telling a tale how an overturned coffee cup could amount to a sentence of death:

If a Druse ever shows cowardice in battle, he is not reproached, but the next time the warriors sit in a circle and coffee is served, the host stands before him, pours exactly as for the others, but in handing him the cup, deliberately spills the coffee on the coward’s robe. This is equivalent to a death sentence. In the next battle the man is forced not only to fight bravely but to offer himself to the bullets or swords of the enemy. No matter with how much courage he fights, he must not come out alive. If he fails, his whole family is disgraced.53

Evolving from the Sludge: African and Arabian Preparations of Coffee

Even though, as we noted at the outset of our discussion, no one has any direct evidence that the Nubians or Abyssinians or tribes of central Africa made use of coffee in ancient times, coffee’s prevalence as both a wild and cultivated plant and its use by modern natives, as observed by Europeans from the seventeenth century onward, suggest ways caffeine may have been ingested before recorded history. A credible tradition holds that in Africa, before the tenth century, a wine was fermented from the pulp of ripe coffee berries, and we have already seen that the Galla warriors rolled the fruit into larded balls, which they carried as rations. Some say that in the eleventh century, the practice of boiling raw, unripe coffee beans in their husks to make a drink was instituted in Ethiopia. Sir Richard Burton’s vivid account of coffee use in the wilds of nineteenth-century Africa includes a description of boiling unripe berries before chewing them like tobacco and handing them out to guests when they visit.

In the early 1880s, Jean Arthur Rimbaud (1854–91), the French expatriate Symbolist ex-poet, laid plans to visit Africa to write a book for the Geographical Society, including maps and engravings, on “Harar and Gallaland.”54 As far as we know, he never got further than writing the title, complete with publisher and projected publication date: THE GALLAS, by J.-ARTHER RIMBAUD, East-African Explorer, with Maps and Engravings, Supplemented with Photographs by the Author; Available from H. Oudin, Publishers, 10, rue de Mézieres, Paris, 1891. Although he never wrote the book, Rimbaud traveled among the Galla, becoming, to his embarrassment, on several solitary expeditions, the first white man the tribal women had ever seen. While among the tribesmen, he partook of their foods, which included green coffee beans cooked in butter.55 A testimonial to coffee’s importance can be found in a letter in which he writes of his distaste at being forced to share coffee with the bandit Mohammed Abou-Beker, the powerful sultan of Zeila, who preyed on European travelers and traders and controlled the passage of all trading caravans as well as the slave trade. Rimbaud needed Abou-Beker’s sanction to travel in that area, and this would not be forthcoming before participating in the ritual sharing of coffee, brought, at the clap of the sultan’s hands by a servant “who comes running from the next straw hut to bring el boun, the coffee.”56

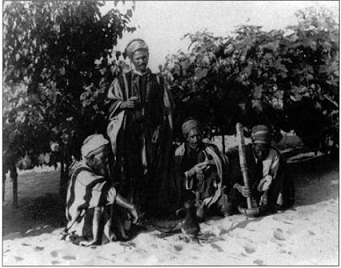

Photograph of Arab peasants making coffee in Gaza, c. 1885–1901. The print is from an albumen photograph taken by Bonfils, who was active from 1864 to 1916. We can see all the stages of the process: the man seated on the left roasts the beans in a pan, the man seated on the right grinds them with a pestle, while the man seated in the center oversees the boiling pot and the remaining man stands with a tiny cup ready to drink the brew. (Photograph by Bonfils, University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia, negative #s4–142208)

We do not know all the details of the earliest Arab preparations. The best information is that, when Arab traders brought coffee back to their homeland from Africa for planting, they made two dissimilar caffeinated drinks from the coffee berry. The first was “kisher” a tealike beverage steeped from the fruit’s dried husks, which, according to every authority, tastes nothing like our coffee, but rather something like an aro matic or spiced tea. In the Yemen, kisher, brewed from the husks that had been roasted together with some of the silver skin, was regarded as a delicate drink and was the choice of the connoisseur. The second was “bounya” its name deriving from “bunn” the Ethiopian and early Arabic word for coffee beans, a thick brew of ground or crushed beans. It was probably drunk unfiltered, and, in a practice persisting for several hundred years, downed with its sediment, a drink that could fairly be called “sludge.” Early bounya was made from raw, boiled beans. A Levantine refinement introduced the technique of roasting the beans on stone trays, before boiling them in water, then straining and reboiling them with fresh water, in a process repeated several times, and the thick residue stored in large clay jars for later service in tiny cups. In another development, the beans were powdered with a mortar and pestle after roasting and then mixed with boiling water. In a practice that persisted for several hundred years, the resulting drink was swallowed complete with the grounds. Later in the sixteenth century Islamic coffee drinkers invented the ibrik, a small coffee boiler that made brewing easier and quicker. Cinnamon, cloves, sugar might be added while still boiling, and the “essence of amber” could be added after the coffee was doled out in small china cups.57 A cover was affixed to the boiler a few years later, creating the prototype of the modern coffeepot.

Infusion was the latest arrival, its development dating only from the eighteenth century. Ground coffee was placed in a cloth bag, which was itself deposited in the pot, and upon which hot water was poured, steeping the grounds as we steep tea. However, boiling continued as the favorite way of preparing the drink for many years.

The Origin of the Word

In pursuing the origin of the uses of the coffee bean, we are led on a chase reminiscent of Scheherazade’s tales in the Arabian Nights. We are quickly lost in a world where names of things and people and places are confounded and uncertain, and where the central subject of our speculation seems to simply have appeared, like a jinn, without revealing the secret of its provenance even to living witnesses of its advent.

The word “coffee” itself is the best example of this dubietous panorama of the fabulous and the real. The word enters English by way of the French “café” which, like the words “caffé” in Italian, “koffie” in Dutch, and “Kaffee” in German, derive from the Turkish “kahveh” which in turn derives from the Arabic word “qahwa” Of this much we may be sure. But once we inquire into the origin of the Arabic word, we are quickly lost in a labyrinth of tantalizing, mutually exclusive etymological conjectures.

One etymological theory with considerable academic support is that the word “qahwa” in Arabic comes from a root that means “making something repugnant, or lessening someone’s desire for something.”58 “Qahwa,” in the old poetry, was a venerable word for wine, as something that dulls the appetite for food. In later usage, it came to refer to other psychoactive beverages, such as khat, a strong stimulating drink infused from the leaves of the kafta plant, Catha edulis, which is still popular in the Yemen. This theory holds that the Sufis took the old word for wine and applied it to the new beverage, coffee. The notion seems particularly appealing when we consider that the Sufi mystics, who sought to empty their minds of circumstantial distractions by whirling furiously until entering an ecstatic state, and who were constrained, like all Muslims, from drinking wine, used wine and intoxication in their poetry as sensual emblems of divine afflatus;59 they might have happily used the word for this forbidden wine to name the new, permitted brew, a drink that would in fact help to sustain their devotions. A variation of this theory is that, just as the word “qahwa” was used for wine because it diminished the desire for food, it was naturally used for coffee because it diminishes the desire for sleep.

At least one old Arab account says that what we call coffee today borrowed its name directly from the drink brewed from kafta, or khat, after the redoubtable al-Dhabhani recommended to friends that they substitute coffee for the qahwa made from kafta, when supplies of the latter were exhausted. According to this notion, coffee is a kind of poor man’s khat, to which the Sufis resorted only when khat was unavailable. This preference may still obtain today in the Yemen, where the more profitable cultivation of khat, despite government efforts to discourage khat’s use, is increasingly displacing the cultivation of coffee.60

Still another etymology, but one with slight lexicographical authority, traces the word “coffee” to “quwwa” or “cahuha,” which means “power” or “strength,” holding that the drink was named for what we now recognize as the envigorating effects of caffeine. A story advancing this etymology is that, toward the middle of the fifteenth century, a poor Arab traveling in Abyssinia stooped near a stand of trees. He cut down a tree covered with berries for firewood in order to prepare his dinner of rice. Once done eating, he noticed that the partially roasted berries were fragrant and that, when crushed, their aroma increased. By accident, he dropped some of them into his scanty water supply. He discovered that the foul water was purified. When he returned to Aden, he presented the beans to the mufti, who had been an opium addict for years. When the mufti tried the roasted berries, he at once recovered his health and vigor and dubbed the tree of their origin, “cahuha.”61

An evocative etymology provided for the word “coffee” links it to the region of Kaffa (now usually spelled “Kefa”) in Ethiopia, which is today one of Africa’s noted growing districts.62 Some say that because the plant was first grown in that region, and was possibly first infused as a beverage there, the Arabs named it after that place. Others, with equally little authority, turn this story on its head and claim that the district was named for the bean.

But perhaps the best fabulous etymology combines two of these theories and throws in a prototypical Arabian fantasy of the divine, the demonic, and the marvelous. It accepts that coffee was named for Kaffa and at the same time links the word “qahwa” in the sense of “wanting no more,” to the name of the district. The idea is based on several Islamic tales that derive the name “Kaffa” from the same Arabian root for “it is enough” as mentioned above:

A priest…is said to have conceived the design of wandering from the East towards Western Africa in order to extend the religion of the prophet, and when he came into the regions where Kaffa lies, Allah is reported to have appeared to him and to have said, “It is far enough; go no further.” Since that time, according to tradition, the country has been called Kaffa.63

There, of course, the priest promptly discovered a coffee tree laden with red berries, which berries he immediately boiled, naming the brew after the place to which Allah had led him.