2

tea

Asian Origins

If Christianity is wine, and Islam coffee, Buddhism is most certainly tea.

—Alan Watts, The Way of Zen (1957)

From ancient times, the Chinese have elaborated a pretense of tradition and descent that can best be described as a dream of antiquity in a time that never was. Affecting to trace her customs, philosophies, and pedigrees to a more venerable age than those of other nations, the Chinese culture has, in the mirror of mythological history, assumed the cloak of dignity that accords with precedence. Because tea has long been uniquely prominent in Chinese life, an effort to locate its origin in the remote past became inevitable.

Such an effort was realized in the legend of Shen Nung, mythical first emperor of China, a Promethean figure, honored as the inventor of the plow and of husbandry, expositor of the curative properties of plants, and, most important for our story, the discoverer of tea. According to the legend, Shen Nung sat down in the shade of a shrub to rest in the heat of the day. Following a logic of his own that would have appeared mysterious to an onlooker, he decided to cool off by building a fire and boiling some water to drink, a practice he had begun after noticing that those who drank boiled water fell sick less often than those who imbibed directly from the well. He fed his fire with branches from a tea bush, and a providential breeze knocked a few of the tiny leaves into his pot. When Shen Nung drank the resulting infusion, he became the first to enjoy the stimulant effect and delicate refreshment of tea.1

Shen Nung, true to his cognomen, “Divine Healer,” details the medicinal uses of ch’a, or tea, in the Pen ts’ao, a book-length compilation of his medical records, dated, with daunting precision by much later scholars, at 2737 B.C. The entries in this book include unmistakable references to the diuretic, antibacterial, bronchodilating, stimulating, and mood-enhancing effects we now attribute to caffeine:

Good for tumours or abscesses that come about the head, or for ailments of the bladder. It [ch’a] dissipates heat caused by the phlegms, or inflammation of the chest. It quenches thirst. It lessens the desire for sleep. It gladdens and cheers the heart.2

In fact, the earliest edition of the Pen ts’ao dates from the Neo-Han dynasty (A.D. 25 to 221), and even this book does not yet mention tea. The tea reference was interpolated after the seventh century, at which time the word “ch’a” first came into widespread use.

Another traditional account purporting to tell about the early use of tea by an ancient emperor says that, as early as the twelfth century B.C., tribal leaders in and around Szechuan included tea in their offerings to Emperor Wen, duke of Chou and founder of the Chou dynasty (1122–256 B.C.). Wen was a legendary folk hero and purported author of the Erh Ya, the first Chinese dictionary. However, because the earliest extant source for this tea tribute is the Treatise on the Kingdom of Huayang, by Chang Ju, a history of the era written in A.D. 347,3 the story is not very helpful in establishing that tea was used in China before the first millennium B.C.

To Lao Tzu (600–517 B.C.), the founder of Taoism, is ascribed, by a Chinese text of the first century B.C., the notion that tea is an indispensable constituent of the elixir of life. The Taoist alchemists, his followers, who sought the secret of immortality, certainly believed this, dubbing tea “the froth of the liquid jade.” (Unlike their Western counterparts, who searched for both the secret of eternal life and the power to turn base metal into gold, the Chinese alchemists confined their quest to improving health and extending life.) The custom of offering tea to guests, still honored in China, supposedly began in an encounter that occurred toward the end of Lao Tzu’s life. An embittered and disillusioned man, the spiritual leader, having seen his teachings dishonored in his own land and foreseeing a national decline, drove westward on a buffalo-cart, intending to leave China for the wild wastes of Ta Chin in central Asia, an area that later became part of the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire. The customs inspector at the Han Pass border gate turned out to be Yin Hsi, an elderly sage who had waited his entire life in the previously unsatisfied expectation of encountering an avatar. Recognizing the holy fugitive and rising to the occasion, Yin Hsi stopped Lao Tzu, served him tea, and, while they drank, persuaded him to commit his teachings to the book that became the revered Tao Te Ching, or The Book of Tao.

Probably what was genuinely the earliest reference in Chinese literature adducing the capacity of tea, through what we now know is the agency of caffeine, to improve mental operations is found in the Shin Lun, by Hua Tuo (d. 220 B.C.). In this book, the famous physician and surgeon, credited with discovering anesthesia, taught that drinking tea improved alertness and concentration, a clear reference to what we today understand as caffeine’s most prominent psychoactive effects: “To drink k’u t’u [bitter t’u] constantly makes one think better.”4

Awareness of caffeine’s efficacy as a mood elevator was also evidenced in Liu Kun, governor of Yan Chou and a leading general of the Qin dynasty (221–206 B.C.), who wrote to his nephew, asking to be sent some “real tea” to alleviate his depression. In 59 B.C., in Szechuan, Wang Bao wrote the first book known to provide instructions for buying and preparing tea.5 The volume was a milestone in tea history, establish ing that, by its publication date, tea had become an important part of diet, while remaining in use as a drug.

One of the most entertaining stories about tea to emerge from Oriental religious folklore is a T’ang dynasty (618–906 A.D.) Chinese or Japanese story about the introduction of tea to China. This story teaches that tea’s creation was a miracle worked by a particularly holy man, born of his self-disgust at his inability to forestall sleep during prayer. The legend tells of the monk Bodhidharma, famous for founding the school of Buddhism based on meditation, called “Ch’an,” which later became Zen Buddhism, and for bringing this religion from India to China around A.D. 525. Supposedly, the emperor of China had furnished the monk with his own cave near the capital, Nanging, where he would be at leisure to practice the precursor of Zen meditation. There the Bodhidharma sat unmoving, year after year. From the example of his heroic endurance, it is easy to understand how his school of Buddhism evolved into za-zen, or “sitting meditation,” for certainly sitzfleisch was among his outstanding capacities.6 The tale is that, after meditating seated before a wall for nine years, he finally fell asleep. When he awoke and discovered his lapse, he disgustedly cut off his eyelids. They fell to the ground and took root, growing into tea bushes containing a stimulant that was to sustain meditations forever after.

The Origin of the Word and the Drink

Tea, despite these legends of its antiquity, is, in the long view of things, but a recent introduction to China. The Chinese probably learned of it from natives of northern India, or, according to another account, from aboriginal tribesmen living in Southeast Asia, who, we are told “boiled the green leaves of wild tea trees in ancient kettles over crude smoky campfires.” Some Chinese histories report that tea was brought to China from India by Buddhist monks, as the Arab accounts tell us that coffee was introduced into Arabia from Abyssinia by Sufi monks, although, as with the Arab stories, we have no unequivocal proof these stories are true. Nevertheless it is clear that, though in the West we strongly associate tea with China in the way that we associate coffee with Arabia, each was regarded as an exotic drink when introduced into its respective “region of origin” within historical times. The details of tea’s pre-Chinese history, like the details of coffee’s pre-Arabian history, are unfortunately lost.

From the time tea arrived, however, the Chinese words for tea provide a kind of chronological map which reveals the contours of the plant ‘s history there. The Chinese character “ch’a” the modern Mandarin word for tea, is, except for a single vertical stroke, identical with the character “t’u.” “T’u” is used in the Shih Ching, or Book of Songs, one of China’s oldest classics (c. 550 B.C.), to designate a variety of plants, including sowthistle and thrush and probably tea as well. Typical phrases in which the word occurs: “The girls were like flowering t’u,” “The t’u is as sweet as a dumpling.”7 Although the choice of renderings of “t’u” into English are somewhat arbitrary and fanciful, it is clear that the word referred to a drink of some sort at least as early as the sixth century B.C. From that time forward, one or another of the words for tea was included in every Chinese dictionary.

The “tea change” in terminology occurred during the Early Han dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 24), as recorded in the seventh-century work The History of the Early Han, by Yen Shih-ku, who notes that at that time the switch occurred from “t’u” to “ch’a” when “ch’a” when the tea plant was being specified. This change was even read into the names of places. For example, “T’u Ling,” the “Tea Hills” in the Hunan province, an important and ancient tea-producing region, was redubbed “Ch’a Ling” during the Han dynasty.

Another dictionary, the Shuo Wên, presented to the Han emperor in A.D. 121, defines “ming” as “the buds taken from the plant t’u,” which strongly suggests that the Chinese were already aware that the bud is the best part for making the beverage and that carefully plucking it forces the plant to produce new flush.

The shift to “ch’a” is confirmed in the edition of the Erh Ya prepared by Kuo P’u, an A.D. fourth-century redactor who completely recast the lexicon, dividing it into nineteen parts. Despite the tradition attributing the Erh Ya to the Emperor Wen in the twelfth century B.C., it was written much later, probably around the third or fourth century B.C. Tea appears in P’u’s edition seven hundred years later as “chia” defined as “bitter t’u,” “and the text explains, “The plant is small like the gardenia, sending forth its leaves even in the winter. A decoction is made from the leaves by boiling.”8 This drink was strictly a medicinal preparation, used to alleviate digestive and nervous complaints, uses strongly suggesting the pharmacological actions of caffeine, and it was also sometimes applied externally to palliate rheumatic pains. By A.D. 500, the Kuang Ya, yet another dictionary, defines ch’a as an enjoyable drink, and it was in this period that the use of tea as a comestible became predominant over its pharmacological applications.9

In a striking parallel with the evolution of the word “qahwa” the Arabic word for coffee, which, as we have seen, began as an old Arabic word for wine and a variety of stimulating infusions, the word “cha” originally designated a panoply of decoctions from herbs, flowers, fruits, or vegetables, some of which were intoxicating. This old generic sense survives in contemporary Mandarin, in which any cooling liquid comestible, from bean soup to beer, is called “liang cha” or “cooling tea.” It was only in the time of the T’ang dynasty and the publication of Lu Yü’s Ch’a Ching that ch’a’s meaning underwent the pattern of change linguists call “specialization,” and the word “cha” came predominantly to designate Camellia sinensis, the plant that carried caffeine, and the beverage infused from its leaves.10

The English word “tea” and its cognates in many languages derive from the Chinese Min form, “te,” which may itself be one of China’s most important contributions to the story of the beverage worldwide. In a linguistic transformation opposite to that of the Chinese “ch’a,” the English the word “tea” has undergone “generalization,” and the word, which when it first entered our language designated a single species of plant and the brew made from it, now refers to virtually any infusion of leaves or herbs.

From the time of the Han dynasty tea as a drink grew steadily in popularity. During succeeding dynasties, it spread quickly in the south and more slowly in the north, until, by the Jin dynasty in A.D. fourth-century tea was acknowledged widely as a medicinal and was also generally used as a beverage. Records indicate that it was prescribed by a Buddhist priest to relieve a Jin emperor’s headache. It was from this time, when demand had so increased that it could no longer be met by harvesting wild tea trees and stripping their branches, that the first cultivation of tea is dated.11 In A.D. 476 Chinese trade records reveal that it had already been used as barter with the Turkic tribes.12 In the Sui dynasty (A.D. 589–618) tea was introduced by Buddhist monks into Japan.

We have already noted three of the most interesting parallels between the apparently unconnected histories of coffee and tea: Each was first harvested as a wild leaf or berry and used only as a stimulant and a medicine; each was first cultivated and used as a beverage relatively recently; and each was brought into the regions that today are associated with its origin by religious devotees returning from a nearby country, who initially used it to stay awake during their meditations. Another parallel is the way the Chinese tried to keep tea cultivation to themselves, just as the Arabs tried to do with coffee. Finally, almost from its first appearance in China, tea leaves were used as a medium of exchange, as were coffee beans in Arabia, cola nuts in Africa, and cacao pods and maté leaves in the Americas. Bricks pressed from dried tea leaves served as currency among the peasantry of the interior, who preferred them to either coins or paper money, which diminished in value as one traveled farther from the imperial center.13

Tea’s wild popularity in China dates only from the T’ang dynasty, a golden age in China’s genuine history, when her power, influence, scope, attainments, and splendor were reminiscent of the late Roman Republic or the early Roman Empire; for as Rome had been hundreds of years earlier, the Chinese empire in its T’ang heyday was the most extensive, most populous, and richest dominion in the world. It was in this period that the Japanese, idolizing T’ang culture, adopted tea drinking as part of their efforts to emulate their neighbors. During the reign of T’ai-tsung (627–49), China extended her power over Afghanistan, Turkistan, and Tibet. Succeeding emperors brought Korea and Japan under China’s rule, and additional consolidations were effected by Empress Wu (r. 690–705), one of China’s rare women sovereigns. The T’ang government and the T’ang code of laws, resting on Confucian teachings, became models for neighboring countries. Towns grew in size and prosperity, foreign trade increased, bringing new cultural ideas and new technologies, and, in this cosmopolitan milieu, the arts flourished. A custom instituted in the seventh century under the reign of the T’ang ruler T’ai Tsung, of paying a tea tribute to the emperor, continued through the Ch’ing dynasty (1644–1911), the last imperial dynasty of China. During the T’ang dynasty, a time of luxuries and refinements, individual tea trees were celebrated for the quality of their leaf. For example, one called the “eggplant tree” grew in a gully and was watered by the seepage from a rock above. It was also during this dynasty that Chinese tea merchants commissioned Lu Yü to write a manual of tea connoisseurship, The Classic of Tea (Ch’a Ching).

The Classic of Tea: Teaching Tea Tippling

Sometimes one man and one book can have a critical effect on an entire culture. For example, the fact that despite the existence of a generally agreed-upon normative definition of tragedy, there is in the West no corresponding account of comedy, may be traced to the fact that the part of Aristotle’s Poetics treating the tragic drama survived, while that treating the comic was lost. Similarly, that tea in the West has never become the central feature of culture that it is in the East may be a result of the fact that Lu Yü wrote his great book in Chinese rather than in English or French. In the year A.D. 780 the tea merchants of China hired this leading Taoist poet to produce a work extolling tea’s virtues. The result of this public relations effort was a book dealing exhaustively and, for the most part, extremely soporifically, with every aspect of tea. After telling you more than you want to know about the cultivation, harvesting, curing, preparation, apparatus of consumption, and use of tea, Lu Yü closes with anecdotes and quotations from eminent historical figures “whose love of tea and proper conduct resulted in health, wealth, and prestige.”14 As explained in an old preface to his work, Lu Yü has long been acknowledged as the godfather of tea authorities: “Before Lu Yü, tea was rather an ordinary thing; but in a book of only three parts, he has taught us to manufacture tea, to lay out the equipage, and to brew it properly.”15 The earliest surviving edition of the Ch’a Ching dates from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Lu Yü also authored several lost works about tea, probably drawn in even more detail, such as a book distinguishing twenty sources for water in which to boil tea leaves.16

According to legend, Lu Yü was an orphan who was adopted by a Ch’an Bud-dhist monk of the Dragon Cloud Monastery. When he refused to take up the robe, his stepfather assigned to him the worst jobs around the monastery. Lu Yün ran away and joined a traveling circus as a clown, but the adulation of the crowd could not assuage his yearnings for wisdom and learning. He quit show business and immersed himself in the library of a wealthy patron. It was at this time that he is supposed to have begun writing the Ch’a Ching. To Lu Yü, tea drinking was emblematic of the harmony and mystical unity of the universe. “He invested the Ch’a Ching with the concept that dominated the religious thought of his age, whether Buddhist, Taoist, or Confucian: to see in the particular an expression of the universal.”17

No aspect of tea, real, imaginary, or elaborate beyond reason, escaped Lu Yü’s attention. Among his extensive expositions of tea varieties:

Tea has a myriad of shapes. If I may speak vulgarly and rashly, tea may shrink and crinkle like a Mongol’s boots, or it may look like the dewlap of a wild ox, some sharp, some curling as the eaves of a house. It can look like a mushroom in whirling flight just as clouds do when they float out from behind a mountain peak. Its leaves can swell and leap as if they were being lightly tossed on wind-disturbed water. Others will look like clay, soft and malleable, prepared for the hand of the potter and will be as clear and pure as if filtered through wood. Still others will twist and turn like the rivulets carved out by a violent rain in newly tilled fields.

Those are the very finest of teas.18

Here is his reasoned catalogue of waters:

On the question of what water to use, I would suggest that tea made from mountain streams is best, river water is all right, but well-water tea is quite inferior…. Water from the slow-flowing streams, the stone-lined pools or milk-pure springs is the best of mountain water. Never take tea made from water that falls in cascades, gushes from springs, rushes in a torrent, or that eddies and surges as if nature were rinsing its mouth. Over usage of all such water to make tea will lead to illnesses of the throat…. If the evil genius of a stream makes the water bubble like a fresh spring, pour it out.19

Not only does he itemize types of tea and types of water, he even classifies stages of what we might regard as the undifferentiable chaos of boiling. The initial stage is when the water is just beginning to boil:

When the water is boiling, it must look like fishes eyes and give off but the hint of a sound. When at the edges it clatters like a bubbling spring and looks like pearls innumerable strung together, it has reached the second stage. When it leaps like breakers majestic and resounds like a swelling wave, it is at its peak. Any more and the water will be boiled out and should not be used.

The subsequent stage of boiling is described in even more elaborate and fanciful terms:

They should suggest eddying pools, twisting islets or floating duckweed at the time of the world’s creation. They should be like scudding clouds in a clear blue sky and should occasionally overlap like scales on fish. They should be like copper cash, green with age, churned by the rapids of a river, or dispose themselves as chrysanthemum petals would, promiscuously cast on a goblet’s stand.20

As a result of the success of this book, Lu Yü was lionized by the emperor Te Tsung and became enormously popular throughout China. Finally he withdrew into an hermetic life, completing the circular course begun in his monastic childhood, and died in A.D. 804. His story did not quite end there, however. Lu Yü was supposed on his death to have been transfigured into Chazu, the genie of tea, and his effigy is still honored by tea dealers throughout the Orient.

The Forms of Tea: From Bricks to Powder

To make tea into bricks or cakes, the leaves were pounded, shaped, and pressed into a mold, then hung above an open pit to dry over a hardwood or charcoal fire. When ready, the bricks were placed in baskets attached to either end of a pole for delivery to every part of the nation. In earlier times the cakes of pressed leaves were chewed, and later they were boiled with “onion, ginger, jujube fruit, orange peel, dogwood berries, or peppermint,”21 or rice, spices, or milk.22 After the T’ang dynasty the use of brick tea underwent a steady decline. However, throughout the eighteenth century, Chinese brick tea became the favorite of the Russians, who imported millions of tons.

In the Sung dynasty (960–1279), brick tea was largely replaced by a powdered tea that was mixed with hot water and whipped into a froth. Along with the new fashion of preparation came new names for tea varieties, such as “sparrow’s tongue,” “falcon’s talon,” and “gray eyebrows.” The Sung emperor Hui Tsung (1101–24), who widely influenced China’s culture, wrote a treatise championing powdered tea, which helped it attain preeminence. To see how seriously tea was then taken consider that a Sung poet in the Taoist tradition, possibly Li Chi Lai, declared that the three most venal sins were wasting fine tea through incompetent manipulation, false education of youth, and uninformed admiration of fine paintings.23

When China fell under the rule of the Mongols, tea as a cultural force fell into decline. Marco Polo (1254–1324), an avid and meticulous observer of Chinese life and customs, never discusses tea drinking and mentions tea only in connection with the annual tea tribute paid to the emperor. Nevertheless, it was during this era of relative desuetude that the Chinese tea ceremony was born. It existed at least from the Yuan dynasty (1280–1368), for it is described in a 1335 edition of the Pai-chang Ch’ing Kuei, a book of monastery regulations supposedly promulgated by Pai-Ch’ing (d. 814).24

The prominence of tea returned with the reassertion of native imperial power in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). In the Ming dynasty tea was first prepared by steeping the cured leaf in a cup. Some wealthy tea drinkers placed a silver filigree disk in the cup to hold down the leaves. During this period, new methods of curing the leaf were developed, with the result that, when travelers from the West arrived, they encountered leaves fermented to varying extents, which they mistakenly thought were different species: black, green, and oolong. The “pathos of distance,” to use Nietzsche’s phrase, between the extravagant imperial family and their humble subjects is exemplified in the story of a certain rare tea, prepared only for the emperor, which grew on a distant mountain so inhospitable that it could be harvested only by provoking the rock-dwelling monkeys into angrily tearing off branches from the tea trees to hurl down upon their tormentors, who were then able to strip the leaves at their convenience.25 The most celebrated tea of the Ming period was Fukien tea, grown in the hills of Wu I, which the Chinese believed could purify the blood and renew health. It was also during the Ming period that tea ascended to its full status as a ritual enjoyment and a spiritual refreshment that transcended the condition of ordinary comestibles, a standing that it retains to this day.

According to Okakura, the stages of tea development, as epitomized in the manner of tea preparation in each, correspond with the three great historical stages of Chinese civilization and culture:

The Cake-tea which was boiled, the Powdered-tea which was whipped, the Leaf-tea which was steeped, mark the distinct emotional impulses of the T’ang, the Sung, and the Ming dynasties of China. If we are inclined to borrow the much abused terminology of art-classification, we might designate them respectively, the Classic, the Romantic, and the Naturalistic schools of Tea.26

Outside China, the peoples of the Orient had their own special ways of making use of the caffeine in the tea plant. In ancient Siam, steamed tea leaves were rolled into balls and consumed with salted pig fat, oil, garlic, and dried fish. The Burmese prepared letpet, or “pickled tea salad,” by boiling wild tea leaves, stuffing them into a hollow bamboo shoot and burying them for several months, after which they were excavated to serve as a delicacy at an important feast. Tibetans still make tea using blocks of leaves that they crumble into boiling water. Like the early Turkish preparations of coffee, this tea is heavily reboiled. Like the Galla warriors of the Ethiopian massif, who mix ground coffee beans with lard to sustain them in the harsh conditions of high altitudes, the Tibetans, who also struggle with life in a difficult environment, mix their tea with rancid yak butter, barley meal, and salt to make a nourishing breakfast treat or snack.27

Tea and the Tao: Yin, Yang, and the Importance of a Balanced Diet

Tea, in a more highly concentrated, less exhaustively processed form than in later centuries, was one of the important and most powerful ingredients known to ancient Chinese medicine. Long before its fashionable ascension as a comestible in the T’ang dynasty, tea had joined the ranks of ginseng and certain mushrooms to which a considerable body of folklore had ascribed a marvelous range of benefits. The Pen ts’ao kang-mu (1578), an herbal by Li Shih-chen (1518–93), generally thought to contain material surviving from a much earlier period, illustrates the high esteem in which the leaf was held in the traditional Chinese pharmacopoeia. As Jill Anderson says, speaking of tea in China in An Introduction to Japanese Tea Ritual (1991), Li attributed to tea the power to

promote digestion, dissolve fats, neutralize poisons in the digestive system, cure dysentery, fight lung disease, lower fevers, and treat epilepsy. Tea was also thought to be an effective astringent for cleaning sores and recommended for washing the eyes and mouth.28

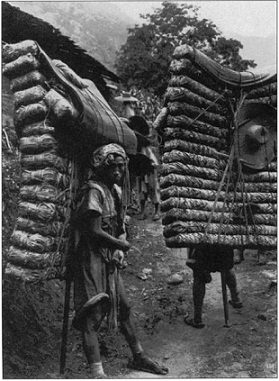

Photograph of Tibetan men carrying brick tea from China, where they had obtained it by barter. They marked about six miles a day bearing three-hundred-pound loads of the commodity, regarded as a necessity in their homeland. (Photograph by E.H.Wilson, Photographic Archives of the Arnold Arboretum, copyrighted by the President and Fellows of Harvard College, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts)

We can only wonder if the recent discoveries that caffeine can increase the rate of lipolysis, or fat burning, has protective effects against the pulmonary complications of smoking and congestive lung disease, kills bacteria, and may be useful for atopic dermatitis, are significantly or only coincidentally foreshadowed in a drug manual that is at least five hundred years old.

The Tao, evocatively translated as “the Way,” is an early Chinese word for the mystical totality of Being, or Nature, of which all things were understood to be part. It comprised two opposing principles, the yin and yang, or the feminine and masculine aspects, the interplay between which was held to generate or constitute the variety of the world’s particulars. The practice of Taoism was intended to enable its adherents to bring their minds and bodies into harmony with the all-encompassing and everywhere present Tao. This attainment was to be achieved by appeals to the gods or ancestral spirits, the proper alignment of houses and burial plots, and, most important for our story, the consumption of a balanced diet, that is, a regimen informed by a knowledge of the yin and yang properties of different foods. Thus, like the humoral theory of Galen, the Taoist medical theory relied on restoring or pre serving the proper interplay of forces within the human organism. In senses analogous to the terminological practice of European humoral theory, foods or medicines were considered “cold” or “hot,” depending on whether they contained more of the female principle or the male. What we know to be caffeine’s pharmacological properties made tea central to Taoist treatments.

One traditional Taoist scheme applied in Lu Yü’s time identifies six vapors or atmospheric influences descending from heaven, an imbalance among which will result in various infirmities. As in the humoral theory, this “atmospheric theory” associates a specific health problem with an excess of each of the vapors. In his notes to his translation of The Classic of Tea, Francis Carpenter lists these six health problems:

- An excess of yin creates chills.

- An excess of yang creates fever.

- An excess of wind creates illness of the four limbs.

- An excess of rain creates illness of the stomach.

- An excess of darkness leads to delusions.

- An excess of light creates illness in the heart.29

According to Carpenter, these vaporal elements combine in various ways to create the five flavors (salt, bitter, sour, acid, sweet); the five sounds or notes of the pentatonic scale (kung, shang, chiao, chih, yü); and the five colors (red, black, greenish-blue, white, and yellow). Any imbalance among them can cause trouble.

The Taoist nutritional theory was carried a step further by those adepts who believed that, through an intense study of the yin and yang of different foods and medicines, they could confect an elixir of life, the use of which would attain a subtler and more complete balance of these properties and a biological stability tantamount to immortality. Although the varying components of this potion included botanicals such as ginseng and mushrooms, and elements such as gold and mercury (lethal metals that were also a favored part of humoral treatments through at least the eighteenth century in the West), in every Taoist recipe tea, perhaps because the stimulating effects of caffeine conferred feelings of strength and power, invariably topped the list of ingredients in the brew.

The Chinese Tea Ceremony: A Confluence of Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian Streams

Lao Tzu and his followers regarded tea as a natural agent that, properly used, could help beneficially transform the individual human organism and, as such, was a tool for the advancement of personal salvation. Confucius, who lived at about the same time as Lao Tzu, saw in the ceremonial use of tea a powerful reinforcement of the conventionalized relationships indispensable to an ethical society. Confucius ennobled the ancient Chinese li, or “ritual etiquette,” into a moral imperative. He taught that, when conjoined with the requisite attitude of sincere respect, conduct guided by decorous ceremony such as ritual tea drinking cultivated the person and allowed him to live harmoniously with his fellows.

The success of Confucius’ program demanded attention to the minute or, some might say, trivial aspects of everyday life. Li required that every detail of a gentleman’s conduct, including “the way his meat was cut or his mat was placed,” determined his character, his relation to others, and even his place in the balance of the cosmos. As time went on, this doctrine devolved into fussiness over the details of etiquette, and eventually came to signify little else. As Anderson says, morality, etiquette, and the methods of maintaining social order became blended indistinguishably: “A gentleman’s social position and access to luxuries (such as tea) were considered morally justified because he observed etiquette appropriate to his social position.”30 The uses of tea came to exemplify this integration of manners and morals better than any other aspect of Chinese society.

The elaborate preparation of tea fit easily into this way of understanding things, as Lu Yü, over a thousand years after Confucius, was to make clear in his The Classic of Tea. Typifying the Confucian response to Taoism, Lu Yü’s work reflects the affirmation of both Confucian social decorousness and the Taoist cosmic harmonies that were to shape the tea ceremony in later centuries. Anderson says of The Classic of Tea, “The passages that emphasize the value of moderation in tea-drinking and lifestyle; close attention to detail, cleanliness, and form; and the careful consideration of the guest’s comfort are particularly significant as each point evinces a Confucian regard for li.”31

These were the early cultural precursors to the development of the tea ceremony. But its most immediate sources, as it has come to be practiced for more than a thousand years, were the rituals and beliefs of Ch’an Buddhism. Ch’an, one of the three streams into which the Indian Mahayana Buddhism diverged on entering China, and which was to become the progenitor of Zen Buddhism in Japan, taught that nirvana, Buddhahood, or salvation could be sought through the austere cultivation and emptying of the mind and could be attained in a sudden flash of insight, or Enlightenment. Not surprisingly, all those who proclaimed themselves spiritual descendants of Buddha claimed that their teachings were true to Gautama’s Way. But the Ch’an Buddhists were, in this respect, the most authentic. For Buddha himself had rejected the rituals and substantive doctrines of Hinduism, because he rejected attachment to any ritual or any doctrine or indeed to any affection or assertion whatever. Buddha therefore taught no doctrine but instead guided his followers on the Way of salvation from suffering, advising that after the desires for sex, food, glory, money and other worldly lusts had been overcome, our last remaining pernicious attachments are to ideas, the belief that one thing is so and another thing not so. True to the original quest of the Buddha, the Ch’an monks initiated use of the kung-an, forerunner of the Zen koan, as a way of freeing the mind from what they understood to be the limitations of logic and the intellect. Following Hui-neng (E’no, 638–713), one of Ch’an’s founders, who taught that enlightenment could occur at any time or place in ordinary life, Ch’an disciples rejected both scriptural authority and philosophical texts, turning away from orthodox ritual practices. The tea ceremony, in which a commonplace of life attains a kind of mystical, contemplative, and emblematic dimension, became the external embodiment of their religious quest.

The early Ch’an monks who drank tea did so from a single large bowl which they passed around in a circle, as the Sufi devotees were to do in sharing coffee hundreds of years later. This custom is mentioned in Pai-chang Ch’ing Kuei, a book of monastery regulations supposedly promulgated by Pai-Ch’ing (sometimes known as Huai-hai, Hyakujo Ekai, or Riku).32 However, in the earliest recorded example of the Ch’an tea ceremony, the host would present each participant with his own bowl of powdered tea, add hot water, and whip it vigorously. As we will see in chapter 9, this led smoothly into chado, or the Way of Tea, and chanoyu, or the tea ceremony, in Japan.

The Chinese contributed importantly to the creation of the tea ceremony and incorporated within it symbols from several philosophical systems. However, when compared with what Anderson calls the “full-blown cognitive synthesis later to be realized in Japan,”33 the Chinese experience can be seen to represent only an early stage of the chado’s development. Therefore, although it was in China that the integration of Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist spirituality in the tea ceremony had its beginning, it was only in Japan, where indigenous Shinto and other influences came into play as well, that the tea ceremony developed into a central transformational device advancing the Buddhist quest for enlightenment.

Teahouses in China date from the thirteenth century, becoming, in the Ming dynasty, important centers of social life. Like coffeehouses in the Islamic world and Europe, they played a large part in the political life of the country—for example, the 1911 revolution was plotted in the back room of a Shanghai teahouse.34 Again, it was only in Japan, however, after tea’s conquest of that country in the seventeenth century, that the teahouse and tea garden, like the tea ceremony, reached their full development.

Europeans, the world’s greatest explorers, returned with stories of the Islamic enthusiasm for coffee and coffeehouses within about a hundred years of their inception in the Middle East. However, no travelers returned to Europe from China as witnesses to the days of the Chinese encounter with tea, because none visited there in ancient times. By the time anyone from Europe knew about tea or tea drinking, both the commodity and practice had been familiar in China for at least two thousand years. Therefore, we have no travelers’ tales to give us outsiders’ impressions of the first ebullient days of tea in China.

Arab traders knew of tea by A.D. 900, but the first references to tea by Europeans (after Polo’s) came more than six hundred years later, for it was first named in print in the West in 1559 in a book by a Venetian author celebrated for accounts of adventurous voyages in ancient and modern times. A short time later, in 1567, two Russian travelers brought glowing reports of the plant upon their return from China. It wasn’t until the beginning of the seventeenth century, toward the end of the Ming dynasty, that a Dutch ship left Macao with a bale of tea leaves for delivery to Amsterdam, which became the first tea known to have reached the West.