4

monks and men-at-arms

Europe’s First Caffeine Connections

The main benefit of this cacao is a beverage which they make called Chocolate, which is a crazy thing valued in that country. It disgusts those who are not used to it… [but] is a valued drink which the Indians offer to the lords who come or pass through their land. And the Spanish men—and even more the Spanish women—are addicted to the black chocolate.

—José de Acosta, S J., commenting on chocolate use in Mexico, Natural and Moral History, 1590

In 1502, on his fourth voyage across the Atlantic, Columbus overshot Jamaica and anchored at Guanaja, one of what are today called the Bay Islands, thirty miles off the Honduran coast. While stopping among the Maya villagers, he became the first European on record to have encountered cacao beans. On August 15, Columbus was among the members of a scouting party dispatched from the Spanish ships that encountered two 150-foot canoes propelled by slaves tied to their stations by their necks. One of these great boats, which resembled Venetian gondolas, was captured without incident. It turned out to be filled with trading goods, including cotton clothing, stone axes, and copper bells from the Yucatán Peninsula and carried women and children under a shelter of palm leaves. A description of the meeting was recorded in a 1503 Spanish account, written in Jamaica by Columbus’ son, Ferdinand, and finally published, in a corrupt Italian edition, seventy years later, in Venice:

For their provisions they had such roots and grains as are eaten in Hispaniola…, and many of those almonds which in New Spain [Mexico] are used for money. They seemed to hold these almonds at a great price; for when they were brought on board ship together with their goods, I observed that when any of these almonds fell, they all stooped to pick it up, as if an eye had fallen.1

What he called “almonds” were actually cacao beans. Columbus’ party was impressed by the high value placed on the beans by the natives; but because they had no translator, they failed to discover cacao’s use in making chocolate. Nevertheless, Columbus brought back some of the pods for King Ferdinand of Spain, and these were the first caffeinated botanicals known to have reached Europe.

As we have seen, although Cortés delighted to find in cacao an agent that could stimulate and fortify his soldiers and recommended cultivation of the plant to the young Charles V of Spain, the stories attributing to Cortés the actual delivery of beans to Spain or the preparation of chocolate in Spain have no historical basis. The inventory of Cortés’ American booty, supplied to the king to document the payment of the crown’s share, never mentions cacao. Nor was cacao among the novelties exhibited to the king in 1528 by the returning Cortés, including Europe’s first bouncing rubber ball, a menagerie complete with jaguars and armadillos, and miscellaneous noblemen and human oddities from the New World.

No one knows, or is likely ever to know, which of the myriad commercial, military, or religious Spanish enterprises first brought the beverage to the court. However, chocolate’s earliest documented appearance in Spain came in 1544, when a delegation of Dominican friars transported a group of Maya dignitaries to meet Prince Philip (later Philip II), son of Charles V. The visiting Americans carried rich gifts for Philip, among them vessels filled with chocolate. In 1585, the first recorded commercial shipment of cacao beans reached Seville.

Chocolate Consumes the Spanish Court

Charles V, His Most Catholic Majesty, is credited with achieving the happy admixture of chocolate and sugar, a confection that yielded a drink not only palatable but delicious to Europeans. Cane sugar, imported from the Orient at great cost, had already become available in Europe by the time cacao arrived, and the king blended the two to make a fabulously expensive drink that became a rage at the Spanish court. The cacao paste was also often mixed with vanilla and sometimes with rose water or cinnamon, nutmeg, almonds, pistachios, or even musk, cloves, allspice, or aniseed. Chocolate was enjoyed cold and thick at first, just as it had been by the Aztecs, but within a few years an unknown Spaniard thought up the idea of serving it hot, and a whole new tradition, restoring a more ancient preference of the Maya in this respect, began. Chocolate was thereafter served from a pot, similar to the coffeepot but with the addition of the moliné, a stick for stirring and mixing. The cups into which the chocolate was poured were taller and slimmer than those for coffee or tea, and from their shapes it is possible to determine which of these beverages is being consumed in paintings of the period.

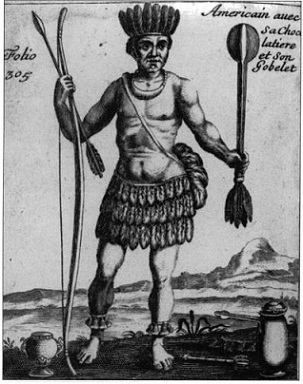

This late-seventeenth-century French engraving features the artist’s conception of an Aztec in feathered regalia, armed with bow and arrow and feathered club, and illustrates a pot for making chocolate, the moliné used for stirring the froth, and the two-handled goblet from which the chocolate was enjoyed. (The Library Company of Philadelphia)

Chocolate, which relies for its analeptic effect on a combination of small amounts of caffeine and larger amounts of the much weaker methylxanthine theobromine, is not as electrifying as coffee in the way these drinks are commonly prepared today. However, the early European chocolateers, like their Aztec and Maya predecessors, cooked their chocolate strong and thick. This chocolate was undoubtedly a powerful stimulant, as well as a nutritious and filling drink; we know that its flavor was strong enough to hide a variety of poisons and that it became the medium of choice through out Europe for dispatching inconvenient persons until at least the time of the French Revolution. The crumbly coarse paste from which it was prepared contained carbohydrates and a large proportion of easily digested fats, protein, and minerals, making it an excellent concentrated high-energy food. This was the special reason that chocolate was so readily taken up by the Catholics of the time and became popular as a clerical resort during fasting. It was only later that chocolate became fashionable among the aristocracy, for whom it served, as many paintings of the period show, as a drink to accompany the start of a leisurely morning.

During most of the sixteenth century, chocolate and the stimulating effects of its caffeine remained a cherished Spanish secret. The Spanish monks enjoyed a de facto monopoly in cacao, and they busied themselves perfecting methods of roasting the beans, brought from Mexico and plantations established in the West Indies and on the African coast. They would grind and shape the hot cacao paste into rods or wafers, leaving them to dry at room temperature, and sell them to aristocratic patrons. Wherever the story of caffeine takes us, we usually find those who have taken religious vows nearby. The Jesuits widely cultivated maté in Paraguay; and the Spanish monks, who took to drinking hot chocolate regularly, became some of their own best customers and were among its most ardent promoters. Also to the Spanish clergy—in this instance, nuns serving in Mexican cloisters—seems to belong the honor of having been the first Europeans to make hard chocolate, a skill they probably learned from native American examples. These nuns are said to have made a great deal of money selling it in confections for the European aristocracy. Most Spaniards who could afford to indulge were caught up in the fad for the new drink, at a time when few other European nationals had even had an opportunity to try it or any other caffeinated product. During this period, Dutch and English raiders who captured Spanish galleons would jettison cacao beans shipped from the growing numbers of Spanish plantations in South America, for they were unaware of the crop’s value as a luxury trade item.

But caffeine secrets are hard to keep, and it was inevitable that the Spanish secret of chocolate, like the Chinese secret of tea and the Islamic secret of coffee, would soon be revealed. For one thing, by the early seventeenth century, Spain had become the center of European fashion and society, and travelers from all over the Continent assembled in Madrid to learn the latest trends. For another, the Spanish monks taught the habit of drinking hot chocolate to their visiting brothers from abroad, who took it home with them. There, among the brothers and laity, it was touted as good tasting and productive of many health benefits and was warmly received.

Cacao Goes to Italy, France, Holland, England, Austria, Switzerland, and Returns Across the Atlantic

Italy was the second European nation where chocolate became popular. In 1606 Antonio Carletti returned from a visit to Spain with the latest recipe for the drink, and his countrymen quickly became avid users. By 1662 its popularity was so great that its use had become a religious issue. The Roman cardinal Brancaccio was called upon to decide whether chocolate offered so much nourishment and sensual satisfaction that its consumption during Lent was unlawful. As Pope Clement VIII had done in 1600 when ruling on coffee, Brancaccio came down on the side of chocolate, stating, “Liq-uidum non frangit jejunum,” which means, “Liquids do not break the fast.”2 This ruling confirmed a use of chocolate that had already made it a popular commodity throughout the Catholic world, for it was highly regarded for sustaining the devoted with nourishment and energy during their fasts.3

France, the third nation to take up the chocolate craze, was introduced to the drink by Spanish Jews who settled near Bayonne in the sixteenth century;4 however, the use of chocolate remained confined to that city, until enjoying a second, royal introduction in 1615. In that year, when each was fourteen, Anne of Austria (actually a Spanish princess) married Louis XIII, bringing in her dowry lavish gifts of cacao cakes, of the sort that would be crumbled and mixed with hot water and sugar for drinking. Thus the French court was initiated to a new luxury. Although the aristocrats embraced Anne’s gift slowly, by the time of Anne’s regency, after Louis’ death in 1643, the most coveted invitation in Paris became “to the chocolate of her Royal Highness.”5 Cardinal de Richelieu, her husband’s tutor, credited chocolate with instilling his remarkable energy, which he applied to duties of state and by virtue of which he had secured for his sovereign the absolute power that would soon descend to the king’s son, Louis XIV (Supposedly Richelieu learned to drink chocolate from his brother Alphonse de Richelieu [1634–80], one of its earliest French adopters, who used the drink as a remedy for his ailing spleen.)6 We do not know if the Sun King recognized this debt to the cacao bean; but it was under his rule and after his marriage to the Spanish princess Maria Theresa in 1660 that chocolate became abidingly popular among the upper classes. It remained in France, as in Spain, an expensive indulgence accessible only to the aristocracy.

Holland was modern Europe’s first republic, and, accordingly, in that country there emerged a pattern of chocolate usage different from that which prevailed in the monarchies. Once the use of the beans was understood, Dutch merchants imported them in great quantities, and the drink of the gods was available to the middle classes. After Holland won her freedom from Spain in the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Dutch began to compete with the Spanish on the lucrative sea routes. Amsterdam quickly became the most important cacao port outside of Spain. Still, today, about 20 percent of the world’s cacao beans pass through Amsterdam, and Holland is the world’s largest exporter of cacao powder, cacao butter, and chocolate.

From Amsterdam, chocolate went to Germany and Scandinavia and crossed the Alps to enter northern Italy, where the Italian chocolate masters created recipes that became popular all over the Continent. Austria imported her chocolate directly from Spain, and only in Austria did chocolate become what could be called a national drink. It may have achieved such general popularity because King Charles VI, unlike other monarchs of his day, kept tariffs on the product low. Chocolate producers in Vienna, who prepared a dozen varieties of chocolate as medicines and beverages, formed a powerful trade organization to establish their interests. An oil painting by JeanEtienne Liotarda, a Swiss painter working in Austria, called La Belle Chocolatière (1743), which depicts a chambermaid bearing the artist’s breakfast drink, is the first known example of chocolate featured in the European visual arts outside of Spain.

It has been claimed, on little or no evidence, that chocolate had been introduced to England in 1520, in the reign of Henry VIII,7 but that the drink made no progress there for more than a hundred years. The first printed mention of cacao in English occurs in Decades W.Indies (London, 1555) by Richard Eden (1521–76) almost half a century before either coffee or tea had been named in print: “In the steade [of money] the halfe shelles of almonds, whiche kinde of Barbarous money they [the Mexicans] caule cocoa or cacanguate.” Another early English reference occurs in 1594 in the works of Thomas Blundevil(le) (1561–1602), who specialized in writing about equestrianism: “Fruit, which the inhabitants cal[l] in their tongue, cacaco, it is like to an Almond…of it they make a certaine drinke which they love marvellous well.”8

We know from these references and others that the English were becoming increasingly familiar with chocolate over the next fifty years. In 1648, Thomas Gage, the Dominican who had traveled throughout the New World, told his countrymen, in New Survey of the West Indies, with the air of imparting a traveler’s oddity, that, among the natives, “All rich or poor, loved to drink plain chocolate without sugar or other ingredients,” presupposing that his readers expected chocolate to be mixed with these things.9

In 1655, during Cromwell’s Protectorate, England acquired some flourishing cacao plantations, which were to become her main sources for the bean, when she wrested Jamaica from Spanish control. In London, in 1657, an expatriate Parisian shopkeeper, proprietor of the city’s first chocolate house, advertised in the Public Adviser, “In Bishopgate Street, in Queen’s Head Alley, at a Frenchman’s house, is an excellent West India drink called chocolate, to be sold, where you may have it ready at any time, and also unmade at reasonable rates.”10

In contrast with Spain and France, where both coffee and cacao were initially trappings of the aristocracy, in England, as in Holland, both were sold to the public in shops almost from the start, to consume there or take out, although at ten to fifteen shillings a pound, these earliest “reasonable rates” were so high that only the prosperous could afford to partake frequently.

Thus, within only five years after London’s first coffeehouse brewed its first cup of coffee in the mid-1660s, competition had arisen from another caffeinated beverage. From about 1675 to 1725 chocolate drinking in coffeehouses was very common, but by 1750 the practice had dwindled to an oddity. Samuel Pepys, who is often associated with the early coffeehouse life of the city, first tried chocolate in 1662 and adopted it, not coffee, as his “morning draft.” The oldest surviving English chocolate pot, specially designed to serve hot chocolate, was made by silversmith George Garthorne in 1685. The chocolate pot was similar in design to the coffeepot, but featured a hole in its hinged finial through which the Spanish moliné, then called a “mill,” was inserted.

Two upscale chocolate houses, White’s and the Cocoa Tree, were established in the 1690s. Schivelbusch, in Tastes of Paradise, says that these chocolate houses had a culture of their own, readily distinguishable from the coffeehouses, which he describes as bourgeois and puritanical. The chocolate houses or chocolate parlors, in contrast, were “meeting places for an odd mixture of aristocracy and demimonde, what Marx would later refer to as the bohème; in any case, they were thoroughly antipuritanical, perhaps even bordello-like places.”11

The English experimented with methods of preparing chocolate, concocting a caudle, or warm spiced gruel, mixed with egg yolk and wine, of the sort then commonly served to invalids or women lying in, surely one of the least appealing ways ever devised for consuming methylxanthines. By about 1730, they had improved the drink by introducing milk in place of or mixed with water.

In England, as elsewhere, tariffs played a major part in determining which of the caffeinated beverages was most used at different times. The alternating vogues, first for coffee, then for tea, and in the rise and fall of chocolate consumption, can be charted from the rising and falling import duties from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries. It was not until the mid-nineteenth century, when the English duty dropped to a penny a pound, that chocolate attained the general use it enjoys there to this day.

From Liquid to Solid: Eating Chocolate Comes of Age

The biggest breakthrough in cacao-processing technology came in 1828, when a Dutch chemist, Coenraad J.Van Houten, patented a press that removed most of the bitter fat, which accounts for more than half the weight, from the ground, roasted beans. He also developed the process of alkalization, still called the “Dutch process,” to neutralize acids and make the resulting powder more soluble in water. Through the use of Van Houten’s invention, two distinct products were produced: a hard cacao cake and cacao butter. The cake was ground into a soluble powder, from which most of the bitterness of the original cacao had been removed along with the fat, and which became very popular as a flavoring. Previously, bakers had been unable to concoct appealing chocolate-flavored pastries because of cacao’s bitterness and graininess. The famous Viennese Sacher Torte, first served in 1832, could not have been prepared before Van Houten.12 Cocoa butter, the other product of the Van Houten process, was the basis of chocolate for eating so familiar to us today. One of the first to produce it was Fry and Sons, of Bristol, who made chocolate bars in 1847. During this time, Lancet, the leading British medical journal, published its analysis of fifty brands of commercial cacao, finding that 90 percent were adulterated with starch fillers or, horrible to contemplate, brick dust and toxic red lead pigment. Cadbury’s stood out as selling a pure product. The most important remaining innovations in chocolate technology were accomplished in Switzerland, when Henri Nestlé invented condensed milk and joined forces with Daniel Peter in 1875 to create the world’s first milk chocolate. Also in Switzerland at this time, Rudolph Lindt devised “conching,” a process by which granite rollers were applied to cacao paste in shell-shaped containers to improve its fineness and homogeneity.

These refinements in processing engendered a complex and sometimes confusing lexicon of terms. The plant (Theobroma cacao) and unprocessed parts of it are called “cacao.” “Chocolate” is a dried paste pressed from the bitter powder of the ground, roasted beans, called “cacao beans” or “cocoa beans,” or the drink made by crumbling this paste and stirring it into hot water. “Cacao powder” or “cocoa powder” is chocolate with most of its bitter fat removed by further pressing, sometimes processed to increase its solubility. “Chocolate liquor” (so called because it starts as a liquid), and “chocolate matter” or “baking chocolate,” a thick, dark paste, are by-products of pressing. “Eating chocolate” is cacao powder mixed with sugar and with “cacao butter” or “cocoa butter,” a light-colored fat that is another by-product of pressing. “Milk chocolate” is eating chocolate with dried milk added.

Consumption has increased more than tenfold since the turn of the twentieth century, commercial cacao cultivation having spread around the world in a belt within twenty degrees of the equator and the varieties of chocolate-flavored confections having proliferated wildly. However, unlike coffee and tea, which, after reaching Europe, were embraced equally by peoples of every continent, the love of chocolate is still developing in Africa and never took hold in the Far East. Even today, it takes a thousand Japanese to eat as many chocolate bars as a typical Englishman in a year.

Considering their American provenance, cacao beans came surprisingly late and by a surprisingly circuitous route to North America, where they were first sold by a Boston apothecary in 1712, having been imported, oddly enough, from England, to which they had earlier been shipped from the West Indies. For many years, only pharmacists sold cacao in the New World colonies, and they used it as an ingredient in their compounded medicines, or “confections.” As with coffee and tea in their early days in Europe, chocolate in the colonies was consumed for its medicinal value and did not immediately achieve its English currency as a tasty and stimulating treat. It was only in 1755 that imports to North America directly from the West Indies were initiated. In 1765, John Hannon, an Irish immigrant, turned an old mill into the first cacao factory in North America.13 Nearly one hundred and fifty years had passed since cacao’s arrival in Europe before cacao came home to the northern part of the hemisphere from which it originated. Once it had done so, it became extremely popular. Milton Snavely Hershey, a veteran sugar candy and caramel maker, bought the German chocolate-manufacturing machinery that he saw exhibited at the 1893 Chicago Exposition and sold his first chocolate bar in 1894. In the ensuing halfcentury, “Hershey bar” became almost a generic name for any chocolate candy bar. In the venerable tradition of using caffeinated seeds and nuts as the basis of highenergy foods, the United States issued chocolates as rations to American soldiers during World War II.