5

the caffeine trade supplants the spice trade

Tea and Coffee Come to the West

After Marco Polo returned to tell tales of his travels in Cathay (1275–94), Venice, increasingly a center of trade and a crossroads for traffic from the East, grew eager to learn more of strange peoples and their strange goods. However, vividly detailed and inclusive as it was, Marco Polo’s book does not mention tea, save in connection with the imperial tax that was levied on its use, reporting that, in 1285, a Chinese minister of finance promulgated an arbitrary increase. Polo failed to say more about tea because, from the standpoint of a visitor to the Mongol court of the Khan, tea was an inconsequential predilection of the subject native Chinese population.

Tea was described, however, in later Venetian travelers’ accounts. After Polo, it was first named in print in the West in 1559 as “Chai Catai” or the “tea of China,” in the posthumous publication Navigatione et Viaggi, or Voyages and Travels, by Giambattista Ramusio (1485–1557), a Venetian author celebrated for accounts of voyages in ancient and modern times. While abroad, Ramusio heard about tea from Hajji Mahommed (or Chaggi Memet), a Persian caravan merchant. After this early notice in Venice, tea was not mentioned again in any known Italian book until 1588, when a 1565 letter of the Florentine Father Almeida was published by the famous author Giovanni Maffei as part of his voluminous collection of traveler’s papers, Four Books of Selected Letters from India (Florence).

Early Portuguese Explorers Encounter Tea

At the same time that the Venetian travelers were making their way back and forth overland to the East in furtherance of the ancient spice trade, the Portuguese explorers, excited by the example of Columbus, were searching for new ways to get to new places. In 1497 Vasco da Gama discovered a sea route to the Indies by way of the Cape of Good Hope. In consequence, the Portuguese were able to expand their explorations eastward, relying on superior armaments to displace the Arab seamen who until then had controlled the exotic trade from India and beyond. They founded a settlement at Malacca on the Malay peninsula. Sailing from Malacca in 1516, the Portuguese became the first Europeans to reach China by sea, where they found favorable opportunities for trade. To make the most of these rich markets, a fleet was soon dispatched to the commercial ports, and an ambassador was sent to Peking. By 1540 the Portuguese had even reached Japan. Finally, as a result of diplomatic persuasions, in 1557 the Chinese allowed them to settle and erect a trading post at Macao, near the estuary of the Canton River (now called the Pearl River).

The Portuguese traders and the Portuguese Jesuit priests, who like Jesuits of every nation busied themselves with the affairs of caffeine, wrote frequently and favorably to compatriots in Europe about tea. Strangely enough, there is no record of their sending tea shipments from the East for the enjoyment of their countrymen. In 1556, Father Gasper Da Cruz, a missionary, became the first to preach Catholicism in China; when he returned home in 1560, he wrote and published the first mention of tea in Portuguese, “a drink called ch’a, which is somewhat bitter, red, and medicinall.”1 Another Portuguese cleric, Father Alvaro Semedo, in 1633 wrote an early account of the tea plant and the preparation of the beverage in his book about China, Relatione della Grande Monarchia della Cina (1643). He mentions the custom, initiated at the Han Pass by Yin Hsi, of offering tea to guests, and explains that when it is offered for the third time, it is time for the guest to move along.

The adventurous Portuguese, though they charted new sea routes for trade around the world, and whose people were the first to enjoy the new influx of spices, silks, and other amenities, failed to participate in the early movement of caffeinated commodities to Europe. Oddly, they were soon to play a seminal role in the tea enthusiasm of England, through the agency of the Portuguese infanta Catherine of Braganza. Her story, as the bringer of many exotic luxuries to her somewhat unsophisticated adopted homeland, when she became the wife of King Charles II, we tell in a later chapter.

For a few decades, the Portuguese faced no competition on the sea routes from the other European powers. England dreamed the impossible dream of sailing across the Atlantic to find a northern sea route to correspond with Magellan’s southern one, while the Swedes and Danes fancied they could discover a similar northern sea route eastward to China. The Germans, weighted down by domestic political conflicts, never even set sail.

However, by closing their trading settlements to rival nations, the Portuguese virtually compelled the English, Dutch, Swedes, Danes, and others to seek out genuine trade opportunities for themselves. In addition to providing stimulus to the Dutch enterprise occasioned by example and exclusion, the Portuguese helped to bring word of tea to their Dutch competitors through the accounts of Jan Hugo van Linschoten (1563–1611), a Dutch navigator and intrepid traveler, who sailed with the Portuguese fleet. In his Linschoten’s Travels (1595), which was translated into English and published in London in 1598, this redoubtable man penned some of the earliest European descriptions of tea and tea drinking, as he met with them in Japan:

Engraving from Dufour’s 1685 treatise on coffee, tea, and chocolate. This French engraving features a contemporary European impression of a Chinese man with his pot of tea and the porcelain cup and saucer in which the tea was served. (The Library Company of Philadelphia)

Their manner of eating and drinking is: everie man hath a table alone, without table-clothes or napkins, and eateth with two pieces of wood like the men Chino: they drinke wine of Rice, wherewith they drink themselves drunke, and after their meat they use a certain drinke, which is a pot with hote water, which they drinke as hot as ever they may indure, whether it be Winter or Summer…the aforesaid warme water is made with the powder of a certaine hearbe called Chaa, which is much esteemed, and is well accounted among them.2

Here we find some of the trappings Europeans still associate with Japan, including saki and chopsticks. As a result of this information and the interest it engendered in Lin Schoten’s countrymen, the introduction of tea to Europe became the work of the Dutch, the great trading rivals of the Portuguese. In the beginning of the seventeenth century, a Dutch ship, sailing from Macao to the port of Amsterdam, brought the first bale of green tea leaves to the Continent. In 1641, the Dutch captured Malacca from the Portuguese and signed a ten-year truce at The Hague ratifying their conquest. The Dutch became the only Europeans allowed to trade in Japan until 1853.

Early Ports of Arrival for Coffee and Tea: Venice, Marseilles, Amsterdam

Before the international trade in coffee began, private persons had brought small quantities of coffee beans into Europe. In 1596, Charles de I’Écluse (Lat. Carolus Clusius) (1524–1609), a French-Dutch physician and botanist, received from an Italian correspondent what were probably the first beans to cross the Alps.3 Within the next decade, Pieter van dan Broeck brought the first beans from Mocha to Holland. But Siegmund Wurffbain (1613–61), a German merchant-traveler, became the first to sell Mocha beans there commercially in 1640. Regular imports to Holland from the Yemen began only in 1663. It is reported that Pasqua Rosée, known to have opened the first coffeehouse in London in 1652, sold coffee publicly in Holland in 1664. Shortly thereafter, the first Dutch coffeehouse was opened in The Hague, and others soon appeared in Amsterdam and Haarlem. The first commercial shipment of Java coffee from the Dutch East Indian plantations, amounting to less than a thousand pounds, did not arrive in Amsterdam until 1711.

The Dutch East India Company, chartered in 1602, investigated the possibility of importing coffee to Holland from the port of Aden in the Yemen as early as 1614, but failed to do so. Venice and Marseilles, from vantages convenient to the Mediterranean, were the first ports to receive commercially imported coffee from Arabia. The first major cargo of coffee beans was shipped into Venice in 1624, most likely having entered the stream of commerce as part of the spice trade from Constantinople, which included silks, perfumes, dyes, and other exotic items. Around 1650 several Marseilles merchants began bringing coffee home from the Levant. Within a few years, a syndicate of pharmacists and merchants instituted commercial imports from Egypt and were soon followed in this business by their counterparts in Lyon. Coffee use became common in those parts of France. In 1671 a coffeehouse opened in Marseilles near the city market, the success of which prompted many imitators, while private use continued to increase.

The sea lanes charted by the Portuguese were quickly overrun with Dutch fleets, and Portugal and Holland began contesting for supremacy in the sea lanes to the East. By 1700, it was clear that the Dutch were the new masters of this burgeoning oceangoing trade around the world. But the story of caffeine in Europe could not expand further, until this explosion of sea trade in the seventeenth and the early eighteenth centuries was combined with international cultivation to make coffee, tea, and cacao available at a popular price.

As Dutch tea imports grew, far exceeding the value of the coffee imports of their French predecessors, Holland became Europe’s first major caffeine connection. In around 1640 in The Hague, the use of tea began to spread as a fashionable and costly luxury, and the beverage was introduced to Germany from Holland by around 1650 and was regularly traded there, appearing on the price lists of apothecaries by 1657. Tea came to Paris in 1648, where it enjoyed a brief fad, as coffee was to do twenty years later. As Thomas Macaulay was the first to notice in print, “tea went through a phase of extreme fissionability there while it was still hardly known in Britain.”4 Gui Patin (1602–72), a Paris physician and writer, called it “nouveauté impertinenté du siècle,” or “impertinent novelty of the century,” in a letter in which he denounced the recent treatise by Dr. Philibert Morisset, Ergo Thea Chinesium, Menti Confert (Paris, 1648), or Does Chinese Tea Increase Mentality?, that, having praised tea as a panacea, was so ridiculed by other medical men that no other doctors in Paris took up the defense of tea for many years.5 Despite the admonitions of most physicians, the public entertained a growing appetite for the drink. According to Father Alexander de Rhodes, in 1653 the tea drinkers of Paris were paying high prices for Dutch tea of poor quality:

The Dutch bring tea from China to Paris and sell it at thirty francs a pound, though they have paid but eight and ten sous in that country, and it is old and spoiled into the bargain. People must regard it as a precious medicament; it not only does positively cure nervous headache, but it is a sovereign remedy for gravel and gout.6

Cardinal Jules Mazaran (Lat. Giulio Mazzarino) (1602–61), a French-Italian cleric and statesman, used tea to relieve his gout. By 1685 tea had become popular among the French literati. Jean Racine (1639–99) grew enamored of tea in his old age, using it as his breakfast drink. As usual in matters pertaining to caffeine, the clergy were leading participants in the literary celebration of the drink. In 1709, the bishop of Avranches, Pierre Daniel Huet (1630–1721), published Poemata, which included the Latin elegy “Thea, elegia” a fifty-eight-stanza encomium of tea. After explaining that tea was planted by Phoebus Apollo in his “eastern gardens,” and watered by “Aurora’s dew,” he plays on the meaning of the Greek word “thea” or “goddess,” and lists the divine gifts that were presented to the young plant. These gifts presaged the marvelous mood-elevating, health-instilling, revitalizing, and intellectually and artistically stimulating powers of the new beverage:

Comus brought joyfulness, Mars gave high spirits,

And thou, Coronide, doest make the draught healthful.

Hebe, thou bearest a delay to wrinkles and old age.

Mercurius has bestowed the brilliance of his active mind.

The muses have contributed lively song.7

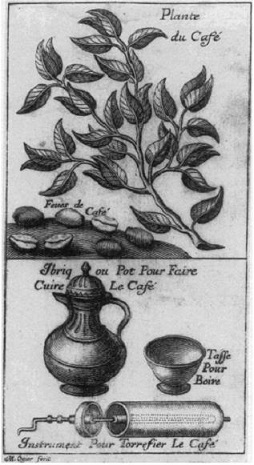

Engraving from Dufour’s 1685 book This two-paneled engraving shows the coffee plant and roasted beans and early Middle Eastern coffee appurtenances. (Department of Special Collections, University of Pennsylvania)

Despite this early flurry of interest in Paris, the predilection for tea abated and, as noted by Pierre Pomet (1658–99), “chief druggist” to Louis XIV and author of Histoire generale des drogues (which appeared in English translation as A Compleat History of DRUGGS), was succeeded within fifty years by a taste for coffee and chocolate. It has never revived since. Tea remained available at great expense from apothecaries, as shown in Pomet’s 1694 price list, which offered Chinese tea at seventy francs a pound and Japanese tea at one hundred and fifty to two hundred francs a pound.

Though the British East India Company had been chartered in 1600, none of the British merchantmen brought back samples of tea (or coffee either) in the early years. On June 27, 1615, R.Wickam, the company’s agent in Hirado, Japan, made one of the earliest known mentions of tea by an Englishman, in a letter to a man named Eaton who was the agent in Macao. The reference is part of a list of desiderata that presupposes his correspondent’s familiarity with the leaf: “Mr. Eaton I pray you buy for me a pot of the best sort of chaw in Meaco, 2 Fairebowes and Arrowes, some half a dozen Meaco guilt boxes square for to put into bark and whatsoever they cost you I will be alsoe willinge acoumptable unto for them.”8 It was not until 1664 that there is any record in the British East India Company’s books respecting a purchase of tea, and that of a shipment of only two pounds and two ounces of “good thea” for a promotional presentation to King Charles II, so that he would not feel “wholly neglected by the Company.”

From this time forward, the Dutch faced a rival in the English, as their competing East India Companies each promoted the sale of its tea and coffee imports throughout Europe. The Dutch took the major step of introducing the coffee plant to Java in 1688, and as a result that island became one of the world’s leading fine coffee producers, giving rise to the epithet “Java” as an enduring nickname for coffee. However, despite Dutch commercial successes, their largely craft-based society failed to grow into a modern industrial economy that could successfully compete in the long run with the one that was to develop in England.

Between 1652 and 1674, there were three largely indecisive wars between the Dutch and English that grew out of their trading rivalry. After 1700, the brief, celebrated Dutch leadership in international trade, science, technology, and the arts increasingly fell into decline, and their fourth and final conflict, fought from 1780 to 1784, ended disastrously for Dutch sea and colonial power. On December 31, 1795, the Dutch East India Company was dissolved, and the triumph of the British East India Company was complete.

Coffee, as well as tea, was both promoted and denounced by Dutch physicians of the time, while the popularity of both drinks continued to increase among all classes. In 1724, the Dutchman Dominie Francois Valentyn wrote of coffee that “its use has become so common in our country that unless the maids and seamstresses have their coffee every morning, the thread will not go through the eye of the needle.” He goes on to blame the English for what he regarded as the deleterious invention of the coffee break, which he calls “elevenses,” after the hour of morning in which it was taken. In the years 1734–85, Dutch imports of tea quadrupled, to finally exceed 3.5 million pounds yearly, and tea became Holland’s most valuable import.

Caffeine Gets the Pope’s Blessing: Acceptance in Italy

According to one story, the encounter between Pope Clement VIII (1535–1605) and caffeine was a fateful one, in which the future of caffeine and perhaps of the pope’s infallible authority (because, despite many decrees by sultans and kings, none banning a caffeinated beverage had lasted long) in much of Europe may well have hung in the balance.

Trade in coffee in Italy before the turn of the seventeenth century was confined to the avant-garde, such as the students, faculty, and visitors at the University of Padua. Whether as a result of the petitions of fearful wine merchants or in consequence of the appeals of reactionary priests, Pope Clement VIII, in the year 1600, was prevailed upon to pass judgment on the new indulgence, a sample of which was brought to him by a Venetian merchant. Agreeing on this point with their Islamic counterparts, conservative Catholic clerical opponents of coffee argued that its use constituted a breach of religious law. They asserted that the devil, who had forbidden sacramental wine to the infidel, had also, for his further spiritual discomfiture, introduced him to coffee, with all its attendant evils. The black brew, they argued, could have no place in a Christian life, and they begged the pope to ban its use. Whether out of a sense of fairness or impelled by curiosity, the pope decided to try the aromatic potation before rendering his decree. Its flavor and effect were so delightful that he declared that it would be a shameful waste to leave its enjoyment to the heathen. He therefore “baptized” the drink as suitable for Christian use, and in so doing spared Europe the recurring religious quarrels over coffee that persisted within Islam for decades if not centuries.

This bar of heaven having been breached, coffee joined chocolate as an item sold by Italian street peddlers, who also offered other liquid refreshments such as lemonade and liquor. There is an unconfirmed story of an Italian coffeehouse opening in 1645, but the first reliable date is 1683, when a coffeehouse opened in Venice.

Early Coffee Stalls and Houses: Ottoman Customs Invade the West

In 1669 Mohammed IV, the Turkish sultan, absolute ruler of the Ottoman Empire, sent Suleiman Aga as personal ambassador to the court of Louis XIV. Their meeting did not go well. Arriving in Versailles, Suleiman was presented to the Sun King, who sat decked in a diamond-studded robe costing millions of francs, commissioned for and worn only on this occasion to overawe his foreign guest. But the rube was not razzed. Suleiman, draped in a plain wool outer garment, approached and stood, unbowing, before the king, stolidly extending a missive that he declared had been sent by the sultan himself and addressed to “my brother in the West.” When Louis, unmoving, allowed his minister to take the letter and said that he would consider it at a more convenient time, Suleiman in astonishment begged to know why his royal host would delay attending to the personal word of the absolute ruler of all Islam. Louis, in answer, and true to the spirit of his motto, “l’état, c’est moi,” coldly responded that he was a law unto himself and bent only to his own inclination, at which Suleiman, with appropriate courtesies, withdrew and was escorted to a royal carriage that conveyed him to Paris, where he was to remain for almost a year.

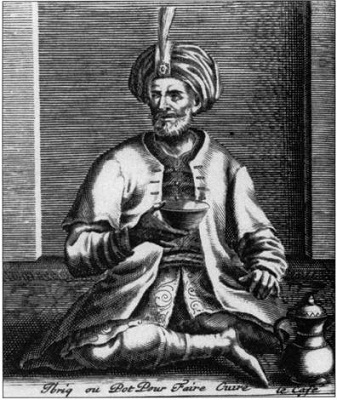

Engraving from Dufour’s 1685 treatise on coffee, tea, and chocolate. This French engraving illustrates a Turk drinking coffee from a handleless cup with an ibrik, or Turkish pot for boiling coffee, standing in the corner. (The Library Company of Philadelphia)

Knowledge of coffee and even coffee itself came to France a hundred years before Suleiman. The earliest written reference to coffee to arrive there was in a 1596 letter to Charles de I'Écluse by Onoio Belli (Lat. Bellus), an Italian botanist and author.9

Bellus referred to the “seeds used by the Egyptians to make a liquid they call cave” and instructed his correspondent to roast the beans he was sending “over the fire and then crush them in a wooden mortar.”10 In 1644 the physician Pierre de la Roque, on his return to Marseilles from Constantinople, became the first to bring the beans together with the utensils for their preparation into the country. By serving coffee to his guests, and turning them on to caffeine, he achieved some notoriety among the medical community. Around this time news about coffee reached Paris, but samples of the beans that were sent there went unrecognized and were confused with mulberry. Pierre’s son, Jean La Roque (1661–1745), famous for his Voyage de L’Arabie Heureuse (1716), an account of his visit to the court of the king of Yemen, records that Jean de Thévenot became one of the first Frenchmen to prepare coffee, when he served it privately in 1657. And Louis XIV is said to have first tasted coffee in 1664.11 Yet, despite all of these precursors, it was Suleiman whose lavish Oriental flair first fired the imaginations of Paris about coffee and the lands of its provenance.

Suleiman, who had made such an austere appearance at court, surprised Paris society by taking a palatial house in the most exclusive district. Exaggerated stories spread that he maintained an artificial climate, perfumed with the rosy scent that presumably filled Eastern capitals, and that the interiors were alive with Persian fountains. Inevitably, the women of the aristocracy, drawn by curiosity and wonder, and perhaps impelled as well by the boredom endemic to their class, filed through his front gate in answer to his invitations. Ushered into rooms that were dimly lit and without chairs, the walls covered with glazed tiles and the floors with intricate dark-toned rugs, they were bidden to recline on cushions and were presented with damask serviettes and tiny porcelain cups by young Nubian slaves. Here they became among the first in the nation to be served the magical bitter drink that would soon become known throughout France as “café.”

Isaac Disraeli paints a rich picture of taking coffee with the Ottoman ambassador in Paris in 1669:

On bended knee, the black slaves of the Ambassador, arrayed in the most gorgeous costumes, served the choicest Mocha coffee in tiny cups of egg-shell porcelain, but, strong and fragrant, poured out in saucers of gold and silver, placed on embroidered silk doylies fringed with gold bullion, to the grand dames, who fluttered their fans with many grimaces, bending their piquant faces—be-rouged, be-powdered, and be-patched—over the new and steaming beverage.12

The women had come seeking intelligence; instead, coffee induced them to supply it. Suleiman spoke fluently of his homeland but confined his remarks to such innocuous matters as stories of coffee’s discovery by the Sufi monks and the manner of coffee’s cultivation and preparation, describing for them the plantations of southwestern Arabia, planted around with tamarisk bushes and carob trees to protect them from locusts.

Meanwhile the well-born ladies, the wives and sisters of the leading military and political men in Louis XIV’s realm, felt their tongues loosening with the expansive effects of a heavy dose of caffeine on nearly naive human sensoriums; for the Turkish coffee Suleiman served, “as strong as death,” boiled and reboiled and swilled down together with its grounds, was some of the strongest ever made. Inevitably, they began to talk, to titter, to chatter, to gossip, their words animated by the stimulant power of caffeine. Thus it was that by the same drug, caffeine, which a few decades earlier in the vehicle of chocolate had enabled Cardinal Richelieu to create the conditions for Louis XIV’s absolute power, that any prospect of securing an alliance with Mohammed IV was now undone.

For it was in this way, by plying the women with strong drink, that the devoted Suleiman, though exiled from the Bourbon court, discovered its inner plottings and strategies and concluded that the Sun King dealt with the Turks only to create apprehension in his old enemy, King Leopold I of Austria, and that Louis could not be relied on by the sultan to send troops to assist, for example, in the next siege of Vienna, which, as it turned out, was less than fifteen years away. Perhaps this was the first time in history when the relations between two great monarchs were in large part conditioned, mediated, and even decided by the power of caffeine.

Although coffee was introduced to the French aristocracy and the common man alike in the time of Louis XIV, because of its limited popularity at Versailles, coffee’s further progress into good society was slow. In any case, so long as Parisians could procure coffee only from Marseilles, only the wealthiest could undertake to provision themselves by sending for a supply. The trappings of Turkish customs, including turbans and imitation Oriental robes, endured a brief enthusiasm among the upper classes. But Turkomania became an object of ridicule, and, accordingly, it and the consumption of coffee soon waned. Molière, in his comedy Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme, produced when Suleiman Aga was still in Paris, mocked the aristocratic cult that indulged in the sacrament of coffee drinking. Perhaps because of the Gallic aversion to foreign intrusions, the French aristocrats, after indulging a momentary dalliance, turned their backs on coffee, at least for the decade, with disdain. The time for caffeine’s wide enjoyment was not to come in France until Louis XV. In order to flatter his mistress, Madame du Barry, who had herself painted as a Turkish sultana being served coffee, Louis spent lavishly to give the drink vogue. He was to commission at least two solid gold coffeepots and direct Lenormand, his gardener at Versailles, to plant about ten hothouse coffee trees, from which six pounds of beans would be harvested annually, for preparation and service to his special friends by the king’s own hands.13

During much of the centuries-long struggle between the Ottoman and Hapsburg Empires, the Armenians, as Christian subjects of the Turks, traveled and traded up and down the Danube, freely crossing the shifting border between the contesting powers. It is therefore no surprise to learn that an Armenian, one Pascal, whether he came to Paris on his own or in attendance to Suleiman Aga, should have become, in 1672, the first to sell coffee to ordinary Parisians. Until then, few people had had the opportunity to drink it. As Heinrich Edward Jacobs says, “It was consumed only occasionally in the houses of distinguished persons, whose family economy was self-contained.”14

Pascal the pitchman, spotting an opportunity, aimed at the bourgeois market when he erected one of the 140 booths that filled nine streets with commercial exhibits and offerings in the gala annual fair in St. Germain, just across the Seine and outside the walls of Paris proper. His maison de caova was designed as a replica of a Constantinople coffeehouse, and its exotic Turkish trappings, when all things Turkish were in vogue among the élite, drew curious members of the public with its mystery and with the novel sweet, roasted scent of fresh coffee. Carrying trays of le petit noir, as it was called, black slave boys darted among members of the street crowd who, either from shyness or inability to find an open space, hung back from approaching the stall itself. Pascal recognized that to make headway with the public, coffee would have to be as cheap as wine; and by importing directly from the Levant and cutting out the Marseilles middlemen, he was able to sell the rare drink for only three sous a cup.

Flush with his success at the fair, the enterprising Pascal decided to open what he intended would be a permanent coffeehouse at Quais de l’École near the Pont Neuf. When business proved slow, he instituted the practice of sending his waiters, carrying coffeepots heated by lamps, from door to door and through the streets, crying “Café! Café!” Despite this aggressive retailing strategy, he soon went broke, packed up, and moved to London. Once there, he may well have headed straight for St. Michael’s Alley in Cornhill, where London’s first coffeehouse had been opened twenty years before by another Armenian immigrant, who, confusingly enough for us, was also named Pascal.

From Then to Now: Café Procope and Other Regency Cafés

Great is the vogue of coffee in Paris. In the houses where it is supplied, the proprietors know how to prepare it in such a way that it gives wit to those who drink it. At any rate, when they depart, all of them believe themselves to be at least four times as brainy as when they entered the doors.

—Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brede et de Montesquieu (1689–1755), personal letter, 1722

Pistols for two; coffee for one.

—Wry commonplace about the orders given before dueling, Paris, La belle Epoque

The world’s first café, a French adaptation of the Islamic coffeehouse, was opened in 1689 in Paris by François Procope. Procope, a Florentine expatriate, started his food service career as a limonadier, or lemonade seller, who attracted a large following after adding coffee to his list of soft drinks. Undeterred by Pascal’s recent failure, Procope decided to target a better class of customers than had the Armenian by situating his establishment directly opposite the Comédie Française, in what is now called the rue de I’Ancienne Comédie. His strategy worked. As the London coffeehouses were doing across the Channel, it attracted actors and musicians and a notable literary coterie. Over the two centuries of its operation as a café, the Procope served as a haunt for such writers as Voltaire, a maniacal coffee addict, Rousseau, Benjamin Franklin, Beaumarchais, Diderot, d’Alembert, Fontanelle, La Fontaine, Balzac, and Victor Hugo. Like Johnson’s famous armchair in Button’s coffeehouse, Voltaire’s marble table and his favorite chair remained among the café’s treasures for many years. Voltaire’s favorite brew was a mixture of chocolate and coffee, which gave him effective doses of both caffeine and theobromine. He is quoted as having remarked of Linant, a pretentious and untalented versifier, “He regards himself as a person of importance because he goes every day to the Procope.”

Like its English counterparts, the Café Procope became a center for political discussions. Robespierre, Marat, and Danton convened there to debate the dangerous issues of the day, and were supposed to have charted the course that led to the revolution of 1789 from the café. Napoleon Bonaparte, while still a young officer, also frequented the Café Procope, and was so poor that the proprietor prevailed on him to leave his hat as security for his coffee bill. The Café Procope was an astonishing success, and from its advent coffee became established in Paris. By one accounting, during the reign (1715–74) of Louis XV there are supposed to have been six hundred cafés in Paris, eight hundred by 1800, and more than three thousand by 1850. According to another more modest reckoning, there were 380 by 1720. Whatever the exact numbers, it is clear that, from the beginning of the eighteenth century, cafés proliferated as rapidly in Paris as the coffeehouses had in London in the last half of the seventeenth century.

Another itinerant Parisian coffee seller, Lefévre, also opened a café near the Palais Royal around 1690. It was sold in 1718 and renamed the Café de la Régence, in honor of the régent of Orléans. Well located to attract an upscale crowd, the café attracted the nobility, who assembled there after withdrawing from paying homage to the French court. The café drew many of the Procope’s customers, and the list of literary and other patrons reads like a Who’s Who of French literature and society over the next two centuries. Robespierre, Napoleon, Voltaire, Alfred de Musset, Victor Hugo, Theophile Gautier, J.J.Rousseau, the duke of Richelieu, and Fontanelle are still remembered in connection with their visits there. In his Memoirs, Diderot records how his wife gave him nine sous every day to pay for coffee at the Régence, where he sat and worked on his famous Encyclopédie. The historian Jules Michelet (1798–1874), writing many years later, gives a vivid account of the ways in which coffee and the café changed and enlivened Parisian life:

Paris became one vast café. Conversation in France was at its zenith For this sparkling outburst there is no doubt that honor should be ascribed in part to the auspicious revolution of the times, to the great event which created new customs, and even modified human temperament—the advent of coffee.

This sudden cheer, this laughter of the old world, these overwhelming flashes of wit, of which the sparkling verse of Voltaire, the Persian Letters, give us a faint idea!15

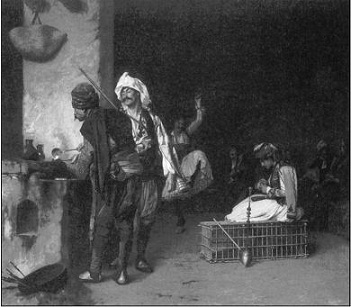

Café House, Cairo, by Jean-Léon Gérome (1824–1904). An example of nineteenth-century French Orientalism, this oil painting shows the coffeehouse as a setting for casting bullets and is reminiscent of the tradition of the French café as the scene of real and imagined revolutionary intrigue. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Henry H.Cook, 1905)

Like the coffeehouses of London, the Parisian cafés attracted a heterogeneous collection of patrons. Charles Woinez announced in his leaflet periodical The Café, Literary, Artistic, and Commercial in 1858, “The Salon stood for privilege, the Café stands for equality.” A similar observation was made in an early-eighteenth-century broadside:

The coffeehouses are visited by respectable persons of both sexes: we see among the many various types: men-about-town, coquettish women, abbés, country bumpkins, nouvellistes [purveyors of news], the parties to a law-suit, drinkers, gamesters, parasites, adventurers in the field of love or industry, young men of letters—in a word, an unending series of persons.16

Despite this pervasive heterogeneity, many Paris cafés catered to special clienteles. Café Procope’s chief rival in regard of attracting poets was the Café Parnasse.17 The Café Bourette also attracted the literati, the Café Anglais was favored by actors and the after-theater crowd, the Café Alexandre was patronized by musical performers and composers, the Café des Art drew opera singers and their entourage, and the Café Boucheries was a place where directors came to hire actors for new productions. But the arts and letters did not have an exclusive hold on the institution. The Café Cuisiner was the favorite of coffee connoisseurs and featured a variety of exotic blends. The Café Defoy was known for sherbet as well as coffee. The Café des Armes d’Espagne was an army officers’ hangout. The Café des Aveugles, which featured musical entertainment by blind instrumentalists, was a den of prostitution.

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, after the Procope and the other cafés had lost their literary reputations, Paul Verlaine, the leader of the Symbolist poets, made the Procope his favorite haunt and thereby partly restored, for a time, its former glory The Procope is still in business today as a restaurant.

Austria: Kolschitzky’s Bean Bags Hit Vienna

The epochal conflict between the Ottoman and Hapsburg Empires well merits the Yiddish epithet “fershlepte kraynk,” which means “long drawn-out difficulty,” for the military, political, and economic rivalry between them began in the fifteenth century and did not abate until almost the end of the nineteenth. As is true for any longtime enemies, each influenced the other, in this case by means of example and trade and through the agency of writers, travelers, merchants, and diplomats. The network of rivalries within Christian Europe, especially the contest between the Protestant Bour-bons and the Catholic Hapsburgs and the vagaries of Louis XIV, who one year was more jealous of the Austrians and the next was more fearful of the Turks, created problems for the West, opportunities for the East, and confusion for everyone.18

The ratification of one of the many peace treaties concluded by the Viennese and the Turks was the occasion for the introduction of coffee to the city. Kara Mah-mud Pasha was a Turkish ambassador who, with an entourage of three hundred, arrived in 1665 to open an embassy in the court of Emperor Leopold I. He spared no effort to impress the local citizens. Kara arrived in Oriental splendor to which the Europeans were unaccustomed, and among his exotic household were camels, Arabian stallions, two coffee brewers, Mehmed and Ibrahim, and a supply of coffee beans. We know that the brewers were kept busy during their several months’ stay, because the city archives record many complaints about the unusually high wood consumption of the Turks, who kept a fire always burning in order to assure a fresh supply of the drink.19 To some extent the habit caught on with the natives. After the ambassador and his retinue departed in 1666, city records report private trade in coffee and that an Oriental trading company, which operated from 1667 until the invasion of 1683, was a primary source for the beans.

The traditional account of coffee’s first appearance in Vienna is considerably different. This folk history dates coffee’s arrival to the 1683 Turkish attempt on the city, a gigantic undertaking, in support of which General Kara Mustafa had led an army of more than three hundred thousand Turkish troops up the Danube from the heartland of the distant eastern empire. The beleaguered city was ringed with twenty-five thousand Turkish tents. Kara settled in for a prolonged siege, during which he sent raiding parties into the surrounding countryside, from the Alps to the Bavarian border. Meanwhile, the Islamic equivalent of the Army Corps of Engineers began tunneling under Vienna’s walls, preparing an entrance for the Janissaries, the empire’s elite troops, to storm. As the situation worsened, the isolated Viennese sent a scout through the Muslim lines to deliver a message to their allies, who had massed just upriver, that the counterattack could be delayed no longer. These Christian troops, led by King John III Sobieski of Poland and Duke Charles of Lorraine, arrived just as the city’s troops poured out of the gate, catching the invaders by surprise and forcing the Islamic general to abandon his camp and hastily withdraw up the Danube. The defeated Turkish armies, in their retreat, took with them over eighty-five thousand slaves captured on these raids, including fourteen thousand nubile girls who would almost certainly be tapped for initiation into the suffocating luxury, enforced helplessness, and fatal intriguing of the Turkish harem. Because of his failure to take Vienna, Mustafa was met on the way home by assassins and suffered strangulation by the gold cord, a death reserved for the sultan’s most intimate enemies.

The Viennese enjoy recalling the glories of their history, and many earnestly commemorate the siege of 1683. As part of this remembrance, Austrian schoolchildren are taught the proverbial story of Georg Kolschitzky, a Pole, who happened to be in town when the assault began, and who is honored for his heroic part in defending the city. Kolschitzky was an adventurer who had traveled widely in the Ottoman domains, serving for a time as a dragoman, or interpreter, in the capitals of the East. Happily, because of his intimate knowledge of the Turkish language and customs, he was able to volunteer service to Vienna as a surveillance agent. On August 13, 1683, Kolschitzky and his servant Milhailovich, each in Oriental disguise, wandered around and through the Turkish encampment northwest of the city. The information they collected about the size and disposition of the enemy forces proved invaluable, or so the story goes. Others say that he was the scout who carried a letter through the enemy lines telling the duke of Lorraine when to attack.

The legend adds that, after the crisis had passed, the city fathers of Vienna asked Kolschitzky to name his reward. He disingenuously asked only for the bags of camel fodder that had been abandoned by the retreating Turks, along with their guns, armor, tents, and other appurtenances of war, and was granted his wish. The “camel fodder,” as he, and he alone in Vienna, well knew, was actually five hundred pounds of green coffee beans, the virtues of which and the methods of roasting, grinding, and boiling he had learned in his travels to the East. Using this supply, he opened the first coffeehouse in Vienna, known as the “Blue Bottle,” but found a limited market. Then he struck upon the idea of using sugar and milk to attenuate the bitter, thick brew. After this innovation, coffee attained the great popularity in Vienna that it has maintained to this day.

The truth about the first coffeehouse in Vienna was more mundane. Vienna’s archives reveal that Kolschitzky was forced to petition the town council for years, reminding them of his valuable wartime services, before being granted a permit to do business in what was then, as now, a tightly controlled and regulation-ridden city. He had run afoul of the trade restrictions of the day, often grounded in the protection of the rights of various guilds to practice their crafts or trades to the exclusion of all outsiders.

Despite the color and charm of the story of Kolschitzky, it is now thought that at least two coffeehouses had been open for business in Vienna, possibly before the siege of 1683 and almost certainly before Kolschitzky’s petition had been granted. Two Armenians, Johannes Diodato and Isaak de Luca, are believed to have been the first to sell coffee from permanent premises.20 Diodato, whose father was a Turkish convert to Roman Catholicism who had settled in Vienna’s thriving Armenian community, obtained the rights to sell Turkish goods in Vienna and enjoyed fabulous commercial success with many commodities. On January 17, 1685, Diodato obtained the first permit in Vienna to open a coffeehouse, although he probably had operated it earlier without benefit of the legal protection from competition that the license afforded. He finally secured a royal monopoly from Leopold I on the sale of coffee in the city for twenty years. Unfortunately for Diodato, his extensive commercial intercourse with the Turks, which was the basis for his success, also brought him under suspicion, and he was forced to flee to Venice in 1693, turning over the operation of his coffeehouse to his wife.

Kolschitzky’s Café, oil painting by Franz Schams. This painting hangs in the main boardroom of Julius Meinl, A.G., an international company that began almost a hundred and fifty years ago as a Viennese coffee-roasting firm. The company’s founder erected a factory on the spot where Kolschitzky found the abandoned Turkish bean bags. (Photograph courtesy of Julius Meinl, A.G., Vienna, Austria)

In 1697 de Luca secured the right to do business in Vienna and married the daughter of a wealthy citizen. Fortunately for him the city fathers were then asserting themselves against the abundance of restrictive royal concessions. Later in the same year, together with two other Armenians, Andreas Pain and Philip Rudolf Kemberg, de Luca acquired a license from the city which gave him, in derogation of Diodato’s royal license, the exclusive right to trade in coffee, chocolate, tea, and sherbet. Diodato’s wife was in no position to argue on behalf of her absent husband, because the royal grant to him had been inalienable. 21 De Luca immediately opened a coffeehouse to take advantage of his new privileges. By the time Diodato returned to Vienna in 1701, he must have been astonished to see the growth of the coffee business. Perhaps promoted effectively by the example of the new Turkish embassy staff, who consumed several tons of coffee a year, coffee had come into almost universal use, and the number of coffeehouses exploded accordingly. In 1714, eleven coffee makers joined to found a trade association, and the coffee trade in Vienna had come of age. As coffee grew in popularity, a bitter contention arose between the coffee-boilers guild and the distillers guild. In 1750 Maria Theresa finally settled the quarrel by forcing the coffee-boilers to sell alcohol as well as coffee and the tavern keepers to sell coffee as well as alcohol, a measure which unified the two guilds.

On the advice of Greiner, one of her ministers, she later imposed a tax on alcohol so heavy that it helped coffee to increase in popularity.

Between the end of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century, from before the First World War to the start of the Second, Vienna became notable for its cafés and café society. People of every sort, from professional men and civil service workers and artists and students, to unemployed laborers and penniless émigrés, would pass hours in the cafés. One of the funniest stories to emerge from this Viennese coffeehouse milieu is about Leon Trotsky:

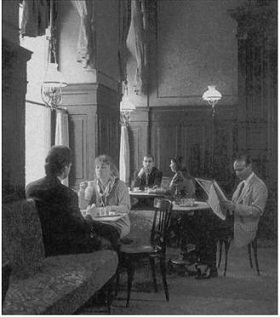

A modern café in Vienna. (Photograph courtesy of Julius Meinl, A.G., Vienna, Austria)

There was a little-known Russian émigré, Trotsky by name, who during World War I was in the habit of playing chess in Vienna’s Café Central every evening. A typical Russian refugee, who talked too much but seemed utterly harmless, indeed, a pathetic figure in the eyes of the Viennese. One day in 1917 an official of the Austrian Foreign Ministry rushed into the minister’s room, panting and excited, and told his chief, “Your excellency… Your excellency… Revolution has broken out in Russia!” The minister, less excitable and less credulous than his official, rejected such a wild claim and retorted calmly, “Go away…. Russia is not a land where revolutions break out. Besides, who on earth would make a revolution in Russia? Perhaps Herr Trotsky from the Café Central?”22

Europeans Improve and Serve Turkish Coffee, Chinese Tea, and Indian Chocolate

A Turkish adage admonishes that coffee should be sweet; but Turkish coffee, as originally prepared, was bitter indeed. Despite this fact, when Vesling visited Cairo in the early seventeenth century, he found two thousand to three thousand coffeehouses, and noted that “some did begin to put sugar in their coffee to correct the bitterness of it, and others made sugarplums of the berries.” Boiled or brewed coffee, as prepared by the Egyptians, Arabs, and Turks, was unpleasant to most European tastes. By 1670, while Viennese traditionalists sat cross-legged and sipped poisonously potent coffee in tiny cups, Eastern style, the first “coffee machines” were being invented in England and France and the Westernization of coffee consumption was under way. These were the first of an abundant variety of devices that culminated in the microprocessor-driven machines of today.

At this time, books instructing the public in coffee preparation began to proliferate. Nicholas de Blegny (1652–1722), a French surgeon who practiced without benefit of a medical diploma, wrote Le Bon Usage du Thè, du Caffe et du Chocolate pour la preservation & pour la guerison des Maladies (Lyons, 1687), or The Proper Use of Tea, Coffee, and Chocolate for the preservation of health and overcoming Diseases, what may be the first European work on the preparation of all three beverages that did more than simply parrot travelers’ accounts. Jacob Spon and Philippe Sylvestre Dufour also provided their readers with good instructions. In 1685 the first serious coffee recipe book was published in Vienna. By the year 1700, books and pamphlets, generally authored by interested parties, such as coffee dealers or coffee-promoting doctors, became common in England and Holland as well.

The single greatest technological revolution in the preparation of coffee was invented by a diligent and creative German housewife in the twentieth century. In 1908, Frau Melitta Bentz, with no more exalted purpose than preparing good coffee to please her husband and her Kaffeeklatsch friends, invented what the world has come to know as “filter drip coffee.” Previously, one or another variations in boiling ground beans had been used exclusively. The result was usually bitter and sometimes laden with the coarse grounds, although even before Bentz’s invention, the use of a cloth bag to screen the boiling grounds had become common. At first she tried linen towels, which did not work well, but then she tried blotting paper placed in a brass pot with a perforated bottom. Pouring water into the brass container, she succeeded in making the world’s first filtered coffee.

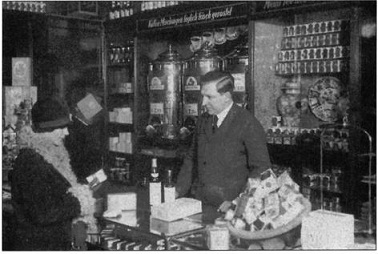

Pre-World War II Viennese fancy grocer on Karntnerstrasse, specializing in coffee and tea, prepared for take-out or bagged for home brewing. (Photograph courtesy of Julius Meinl, A.G., Vienna, Austria)

Bentz soon replaced the blotter paper with a strong porous paper, the sort we are familiar with today, and engaged a tinsmith to produce aluminum pots, more than a thousand of which were sold at the Leipzig Trade Fair. Encouraged by this early success, Bentz’s husband created and assumed the management of a company in 1912, which he named after his wife, to produce the coffeepots and filters. Despite improvements and variations, the basic Melitta method of making coffee, which is simple, dependable, convenient, and produces a rich, clear brew, is still in use today in more than 85 percent of German households and in almost every country around the world.23

The fashions of preparing, serving, and drinking tea also evolved. The Europeans imitated the Chinese, who made tea in unglazed red or brown, plain or decorated stoneware pots, the use of which they believed made for the best brew. These stoneware pots arrived with the first Dutch shipments of tea and were subsequently widely copied by European craftsmen.

The Portuguese and Spanish began to return from the Orient with porcelain as early as the sixteenth century, but, because of porcelain’s expense, its use outside their homelands remained limited.24 This changed when the Dutch began to import large quantities of Chinese and Japanese porcelain, making it cheaper and spreading its use by reexporting it throughout the Continent. It was so cheap in its countries of origin that the Dutch captains loaded their holds with tons of porcelain to ballast their ships, making the previously rare commodity increasingly common. As early as 1615, published accounts make certain that Chinese porcelain was in everyday use in most Dutch homes. As ordinary as these imports had become, some still saw in them the hallmark of exotic splendor. In 1641, the Dutch physician Nikolas Dirx, “Dr. Tulpius,” wrote of the delicate, handleless porcelain cups and opulent tea services that were now being used in his country: “the Chinese prize them as highly as we do diamonds, precious stones and pearls.” Later, so much porcelain was brought into England by that country’s East India Company that it can fairly be said that never, before or since, had ordinary people, poor by our standards, drank or dined with such luxurious appurtenances.

Porcelain was coveted because of its beauty and impermeability, which made it easy to wash. During the seventeenth century, almost all the porcelain brought to Europe was the Ming blue-and-white variety. The Dutch began copying the Ming ceramics and, by the middle of the century, the famous blue-and-white Delft potteries produced credible imitations of the Eastern originals in the chinoiserie style that was later to become popular in Europe.

From the end of the seventeenth century, both coffee and tea services began to assume their modern forms. The first English silver teapot, with a nearly conical shape, was made in 1670. Between 1650 and 1700, the broad flat Chinese bowls were more and more frequently placed on saucers. However, the practice of pouring the coffee from the bowl into the saucer persisted even after handles had been devised for the bowls. This upside-down way of drinking remained customary until the end of the eighteenth century, when drinking from the saucer became socially frowned upon.

Man and Child Drinking Tea, artist unknown, c. 1725. This painting is sometimes called Tea Party in the Time of George I. The silver equipage includes a silver container and cover, a hexagonal tea canister, a hot water jug or milk jug, slop bowl, teapot, and sugar tongs. The cups and saucers are Chinese export porcelain, which was in good supply in the colonies as well as throughout Europe. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

It was also in the eighteenth century that the Germans became adept at designing and producing fine porcelain teapots. By the century’s close, the full development and importance of the modern equipage in Germany is evident in the words of Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840), the Romantic German painter of spiritual, desolate, and brooding landscapes, in a letter to his family, dated January 28, 1818: “Coffee drum, coffee grinder, coffee siphon, coffee sack, coffee pot, coffee cup have become necessaries; everything, everything has become necessary.”25 By the Biedermeier period (c. 1815–48) in Germany and Austria coffee and tea machines and the accompanying porcelain equipage became widely recognized status symbols. Paintings from the period illustrate that the social rank of a family might be accurately estimated from the deliberate display of the items necessary to take morning coffee or tea.