11

the endless simmes

America and the Twentieth Century Do Caffeine

ZING! What a feeling

—Line from Coca-Cola jingle, 1960s

Captain John Smith, who founded the colony of Virginia at Jamestown in 1607, brought the earliest firsthand knowledge of coffee to North America and is sometimes credited with having been the first to bring the beans as well. Smith was familiar with coffee from having traveled through Turkey. Neither the passengers of the Mayflower in 1620 nor the first Dutch settlers of Manhattan in 1624 are recorded to have included any tea or coffee in their cargo. It is impossible to be sure if the Dutch introduced either into their colony of New Amsterdam or whether that distinction belongs to the British, who succeeded them in 1664 and renamed the settlement “New York.” In any case, by the time of the earliest printed reference to coffee drinking in America, which occurs in New York in 1668, the drink, brewed from roasted beans, sweetened with sugar, and spiced with cinnamon, was already in common use. Around this time coffee seems to have displaced beer as the favorite breakfast beverage, and chocolate is recorded to have arrived in small private shipments, primarily as a pharmaceutical. In 1683 William Penn, who probably introduced both coffee and tea into Philadelphia, recorded in his Accounts that he purchased coffee in New York for his year-old Pennsylvania settlement and complained of the price per pound of eighteen shillings nine pence. At this price, the beans required to make a cup of coffee would have cost more than a dinner at an “ordinary,” or informal eatery, of the time. In light of this expense, it is not surprising that, during these first days in the colonies, beer and ale remained the usual drinks at meals other than breakfast, and both tea and coffee were pricey luxuries, with tea the more common of the two, especially in domestic use.

Boston has an early and distinguished place in the American annals of caffeine. Even before any American coffeehouse had opened its doors, Dorothy Jones was granted the first known license to sell coffee in America, in Boston in 1670, though no one knows if she was a purveyor of “coffee powder,” the name for the ground roasted beans, or of the drink itself. It was also in Boston that the London Coffee House, the first coffeehouse in America, opened for business. It constitutes the earliest example in America of the now popular bookshop café, for it is reliably reported that “Benj. Harris sold books there in 1689,” the first year of its operation. Of course, the tradition of selling books in coffeehouses dates back to at least 1657 in London, and after their invention in the eighteenth century, newspapers were printed and sold from the coffeehouses in both England and the New World.

In 1696 the King’s Arms, the first coffeehouse in New York, was opened near Trinity Church by John Hutchins. Its yellow brick and wood structure, with rooftop seating and a splendid view of the city and bay, is supposed to have been standing in Holland when it was purchased, dismantled, and its parts transported to America, where it was reassembled.

The first coffeehouse in Philadelphia was opened by Samuel Carpenter around 1700 on the east side of Front Street, above Walnut Street. Because it remained the only such establishment in the city for some years, it was referred to in the old days simply as “Ye Coffee House.” The Coffee House was apparently used as a post office, to judge from this 1734 excerpt from Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette:

All persons who are indebted to Henry Flower, late postmaster of Pennsylvania, for Postage of Letters or otherwise, are desir’d to pay the same to him at the old Coffee House in Philadelphia.1

Benjamin Franklin (1706–90), always alert to new business opportunities, sold coffee, running an advertisement claiming, “Very good coffee sold by the Printer.” Around 1750 William Bradford, another Philadelphia printer, opened his own London Coffee House, at the southwest corner of Second and Market Streets. It became a thriving center for merchants, mariners, and travelers, and was used as a market for horses, food, and slaves, the last of which were displayed on a platform in the street in front of the coffeehouse.

American coffeehouses, which continued the British coffeehouse traditions as “penny universities” and enhanced their feared and celebrated status as “seminaries of sedition,” soon opened in every colony. At first they were simply taverns serving ale, port, and Jamaican rum, as well as coffee. But soon these coffeehouses featured in American official civic life in ways that had been unknown even in England: Their “assembly rooms” became the sites of court trials and council meetings. The Green Dragon, a coffeehouse tavern and inn, established in 1697, which Daniel Webster called the “headquarters of the Revolution,” was frequented in the next century by Paul Revere, John Adams, James Otis, and other illustrious rebels, and remained open in Boston’s business center for 135 years. Throughout this time, the Green Dragon remained a center of activity, hosting from the first, “Red-coated British soldiers, colonial governors, bewigged crown officers, earls and dukes, citizens of high estate, plotting revolutionists of lesser degree, conspirators in the Boston Tea Party, patriots and generals of the Revolution.”2 The Grand Lodge of Masons, under the leadership of the first grand master of Boston’s first Masonic group, convened there as well.

Colonial American tea tray with cartouch of ladies reading coffee grounds, illustrating the common practice of using grounds for divination, one similar to the practice of reading tea leaves that is more familiar today. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

It was in the Green Dragon that Revere and his co-conspirators are supposed to have met to plan the Boston Tea Party. The story of the Stamp Act of 1765, a British tea tax that turned Americans into some of the world’s most avid coffee drinkers, is well known. Tariffs and taxes frequently determined which of the caffeinated beverages, if any, were within reach of the average person, and had often been designed to do so. The opposition to the British tax prompted the Boston Tea Party of 1773, in which the British East India Company’s cargoes of tea were jettisoned into the harbor. From this moment in history, coffee became the favored caffeinated drink of Americans, indispensable at the breakfast table and the workplace ever after. The Bunch of Grapes, another of the earliest Boston coffeehouses, was the site of the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence.

New York’s Merchants Coffee House, at the intersection of Wall and Water streets, hosted the Sons of Liberty on April 18, 1774, who, following the example of their Boston compatriots, met there to plan their own blockage of British tea imports. The next month, leaders of the revolution gathered there to draft their call for the First Continental Congress. Neither was this coffeehouse forgotten in the aftermath of war and victory. For in 1789, New York City’s mayor and the state’s governor threw a lavish party there in honor of the election of George Washington.

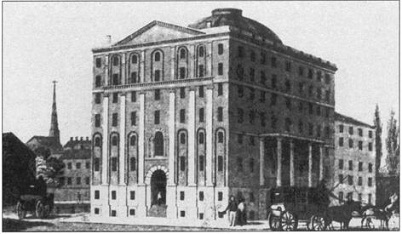

With the opening of the Exchange coffeehouse on Exchange Street in Boston in 1808, the institution reached a kind of acme. The Exchange was modeled after Lloyd’s of London and, like Lloyd’s, served as a center for ship brokers and mariners. Designed by Charles Bulfinch, the most celebrated American architect of the day, it stood seven stories high and was constructed of stone, marble, and brick, at a cost of half a million dollars. In 1817 the Exchange hosted a banquet for James Monroe, attended by John Adams and many other dignitaries. Probably the largest and most expensive coffee-house ever seen in the world, before or since, the Exchange burned down in 1818.

The Exchange Coffee House, Boston. This was the largest and most costly coffeehouse ever built. Erected in 1808, of stone, marble, and brick, it stood seven stories and cost $500,000. It was modeled after Lloyd’s of London, and was, like Lloyd’s, a center for patrons from the shipping business. (W.H.Ukers, All about Coffee)

The early days of American coffeehouses were times of heavy alcohol drinking both in England and the colonies. The English “gin epidemic,” against which the College of Physicians had warned in 1726, asserting that it was a “growing evil which was, too often, a cause of weak, feeble, and distempered children,” continued unabated on both sides of the Atlantic. The revolution and the decades after marked a high level of alcohol use that exceeded any achieved in the twentieth century. In 1785, this widespread drunkenness prompted Benjamin Rush (1735–1814), a famous physician and reformer, to found an anti-alcohol movement, that, like many other such movements since, began by advocating temperance and later advocated abstinence. Rush was as fervent an advocate of the temperance beverages as he was an opponent of the alcoholic ones. His followers, who purchased tens of thousands of copies of his temperance booklets, helped to advance the cause of coffee, tea, and chocolate drinking in the new nation. Yet despite his efforts, around 1800 Americans still annually consumed about three times as much alcohol per person as they were to consume in the 1990s.

Amercia, Land of the Free—Refill

By the second half of the nineteenth century, America was consuming more coffee than any country in the world, and the drink had, in the minds of many of its inhabitants, come to be more identified with their pioneering, robust, democratic country than the stuffy, effete, class-stratified society of Europe. Coffee’s status in America is attested by Mark Twain (1835– 1910) in his travelogue A Tramp Abroad, in which he celebrates coffee, which he has obviously come to regard as quintessentially American, and recounts experiences with it abroad that many American travelers may find familiar today:

In Europe, coffee is an unknown beverage. You can get what the European hotel keeper thinks is coffee, but it resembles the real thing as hypocrisy resembles holiness. It is a feeble, characterless, uninspiring sort of stuff, and almost as undrinkable as if it had been made in an American hotel…. After a few months’ acquaintance with European “coffee,” one’s mind weakens, and his faith with it, and he begins to wonder if the rich beverage of home, with its clotted layer of yellow cream on top of it, is not a mere dream after all, and a thing which never existed.

In an 1892 entry in his Autobiography, Twain presents a somewhat more attractive picture of Italian tea drinking, which he observed while passing through Florence on the way to Germany:

Late in the afternoon friends come out from the city and drink tea in the open air, and tell what is happening in the world; and when the great sun sinks down upon Florence and the daily miracle begins, they hold their breaths and look. It is not a time for talk.3

As the emergent capital of industry and the marketplace and the symbol of revolution and the mixing of peoples, America was the country best fitted to assume leadership in the twentieth-century saga of caffeine. However, if you ask a European visitor what, in his opinion, is the most noteworthy feature of American cafés, he is most likely, instead of mentioning complex ideological or social factors or the characteristic taste complexity of the American roast, to say, “They refill your cup without charge, even without asking!” American readers may wonder why this ordinary courtesy should be regarded as so important. But if you consider that many European coffee lovers and coffeehouse habitués spend hours nursing small cups that cost them twice as much as Americans pay, and that if they want another they must pay the full price again, you can see how, in the course of a life of café hopping, these refills could add up to a small fortune.

Perhaps the endless refill is symbolic of America’s special affection for coffee and of its general culture of largesse and informality as well. Coffee certainly plays the dominant part in the story of caffeine in the United States. Ever since their defiance of British tea taxes inspired the colonials to exchange the leaf for the bean as a patriotic duty, Americans cultivated a taste for coffee to the extent that they became by far the largest single national coffee importers on earth, and today they account for more than half of world coffee imports. Coffee is overwhelmingly the source of most of the caffeine consumed here.

The coffeehouse tradition of troubadour and balladeer, which began in the Middle East in the early sixteenth century, continued in the English coffeehouses of the Restoration (when these establishments became “the usual meeting-places of the roving cavaliers, who seldom visited home but to sleep”),4 and was impressively revived in twentieth-century America, first by the nonconformist Beat Generation of the 1950s and then by the folk and flower child social rebels of the 1960s. The Beat Generation movement began in San Francisco’s North Beach, Los Angeles’ Venice West, and New York’s Greenwich Village. Its members affected an exhausted sophistication and demoralized bohemian irony that put them in the company of a certain tradition of coffeehouse denizens. The apolitical Beat Generation take on café culture is represented by Beat poets Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Allen Ginsberg, who read their works at coffeehouses such as the Coexistence Bagel Shop in San Francisco and emphasized personal fulfillment through self-expression, nonconformity, free love, and the use of drugs and alcohol. Their more socially minded but more drug-dependent hippie successors are represented by folk singers such as Bob Dylan, who began performing professionally in the coffeehouses of Greenwich Village, where he sang Woody Guthrie’s Depression-era songs and others of his own composition to a young audience that had ridden into adulthood on an unprecedented wave of prosperity that had not yet crested. Dylan’s works, and those of his fellow singer-composers, such as Joan Baez and Phil Ochs, helped shape the music of a generation and embodied the social values of the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements.

What are we to make of the coffeehouse renaissance of the 1990s? Certainly it is no flash in the pan. New York real estate prices have seemed high for generations, but they have recently been driven still higher by the competition for space among a new generation of coffeehouse and café proprietors. Many of the new establishments are the progeny of the chain behemoths, such as Starbucks, Timothy’s, and Brothers Gourmet Coffee, each of which boasts many new outlets in Manhattan. Others, like Coopers Coffee and New World Coffee, are the offspring of smaller ventures hoping to expand to compete with their bigger rivals. Bookstores and department stores are increasingly including cafés under their roofs. Some traditional proprietors are benefiting from the upswing. For decades Chock Full o’ Nuts was the ultimate coffeeshop chain, providing cheap but good cups of coffee and fast sandwiches to busy city workers. After ten years of relying on institutional sales and sales of coffee beans and spices, it is again turning to the development of coffeehouses and cafés.

Bubbling Caffeine: The Hard Soft Drinks

The caffeinated drinks, coffee and tea, wherever they were first encountered, were invariably regarded as medicines before they came into use as comestibles. Coca-Cola, the first of the caffeinated soft drinks, also began as a patent medicine, and was first sold in the form of a tonic syrup at pharmacies. Before the turn of the century, however, Coca-Cola had become a popular soft drink that encountered public relations problems, first over its still unverified cocaine content and then because of its caffeine. In the decades since, the Coca-Cola Company has distanced itself from any association in the public’s mind with drugs. Cocaine, if it was ever present in more than a negligible quantity, was eliminated. The caffeine content was cut in half. However, caffeine remains to this day the only pharmacologically active ingredient present in beverages that are dispensed from vending machines, soda fountains, and convenience stores.

Coca-Cola and the Wiley Campaign: Wiley as the Kha’ir Beg of the Twentieth Century

Dr. Harvey Washington Wiley (1844–1930), who at the height of his career enjoyed great national celebrity and power, waged a war against Coca-Cola in the early twentieth century that almost wrecked the company. Like Kha’ir Beg in early-sixteenth-century Mecca, Wiley was a governmental official charged with protecting the public welfare. As the first director of the U.S. Bureau of Chemistry, the forerunner of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Wiley found nothing amusing about the blithe and celebratory indulgence in caffeinated soft drinks that was sweeping the country. Kha’ir Beg had been concerned about social subversion; Wiley was worried about food adulteration and the health of the nation’s children. Each had a large measure of reason on his side.

Wiley saw an essential difference between coffee and tea as caffeinated beverages and Coca-Cola and its imitators. Adults were by far the primary consumers of coffee and tea, and everyone was keenly aware that these drinks contained caffeine. Children, however, were the greatest consumers of Coca-Cola, and most people did not associate the drug with the drink, an association strongly discouraged and underplayed by the company’s brilliant advertising and public relations efforts.5 The epochal conflict between Wiley and the Coca-Cola Company, one of the nation’s most powerful corporations, epitomizes the issues and players that have featured in the centuries-long struggle between caffeine’s purveyors and detractors. In 1902, after twenty years of leading the U.S. Bureau of Chemistry in a fight against the adulteration of food, Wiley achieved national prominence when he created a “poison squad,” a group of twelve young healthy adult volunteers who would test the safety of additives. He campaigned against the nostrums of the patent medicine industry and became a fervent advocate of the frequently proposed and invariably defeated efforts to enact pure food and drug legislation. In 1906 public sympathies began to change, and the Pure Food and Drugs Act, known then as “Dr. Wiley’s Law,” was finally passed. Wiley wasted no time investigating Coca-Cola as a vehicle of caffeine. Headlines appeared in 1907 reading, “Dr. Wiley Will Take Up Soda Fountain ‘Dope.’” John Candler, who was running Coca-Cola at that time along with his brother Asa, was outraged. Candler could not understand Wiley’s animus, asserting, “There can be no more objection to the consumption of caffeine in the form of Coca-Cola than there is to the importation of tea and coffee and their use.”6 The company had no sooner overcome the scandalous rumors about cocaine, which had finally been decisively dispelled, than this new problem over caffeine had arisen. It was to prove more difficult to resolve.

Candler and Wiley had similar backgrounds, including fundamentalist upbringings and training in medicine and chemistry, but they took opposite positions on this central issue. Wiley had no quarrel with caffeine as it occurred naturally in coffee or tea. His lifelong campaign was against adulterants, in acknowledgment of which his followers called him “a preacher of purity,” while his detractors dubbed him “a chemical fundamentalist.” It was from this perspective of concern about adulterants or additives that Wiley saw the caffeine question. He regarded the introduction of the drug into soft drinks as pernicious and deceptive and potentially harmful, especially to the children. Wiley’s positions, which he maintained for the rest of his life, are well represented in his speech in favor of coffee, “The Advantages of Coffee as America’s National Beverage,” and the magazine articles from the same period which he used to batter the Coca-Cola Company.

Wiley was caught in a bind. He had tried to initiate seizures of Coca-Cola, but the federal government refused to cooperate, arguing that caffeine had not been proved harmful and that, furthermore, should it be so proved, coffee and tea would have to be banned as well as Coca-Cola. However, Wiley insisted that if parents really understood that their children were using a drug every time they drank a Coke, there would be more sympathy on his side.

The conflict was finally joined in a federal suit, called, in the legal fashion of such things, The United States vs. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola, which opened in court on March 13, 1911, the second case do so under the new drug laws.7 The witnesses included religious fundamentalists who argued that the use of Coca Cola led to wild parties and sexual indiscretions by coeds and induced boys to masturbatory wakefulness. But most of the testimony was scientific in nature. Coca-Cola presented an array of expert witnesses with impressive credentials. Unfortunately, by today’s standards, the experiments on which their testimony relied were compromised by inadequate protocols. That is, their conclusions tended to support the prior opinions of the investigators regardless of the data actually gathered.

The one exception was the work of Harry Hollingworth, a young psychology professor at Columbia University, and his wife and research assistant, Leta, who designed and performed the first comprehensive double-blind experiments on the effect of caffeine on human health. These studies are still being cited in journal articles today. For example, a 1989 study published in the American Journal of Medicine referenced the Hollingworths’ 150-page 1912 study,8 to the effect that “a total day’s caffeine dose of 710 mg was necessary to lessen subjective sleep quality.” Their careful work demonstrated that caffeine in modest doses improved motor performance and did not disturb sleep. In sum, their work failed to support Wiley’s concerns; although in fairness it must be added that in large part it also failed to address them in any significant way.

Coverage of the trial was frequently sensationalistic, with one headline reading, “EIGHT COCA-COLAS CONTAIN ENOUGH CAFFEINE TO KILL.”9 Wiley himself never testified, leading us to speculate that his group of young food tasters had not experienced any harmful consequences from their exposure to the drink. The case was finally decided on technical grounds that have little to do with caffeine and make little sense. The District Court judge Sanford, who later was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court, directed a jury verdict in favor of Coca-Cola, ruling that their drink was not mislabeled, because it did contain minute amounts of both cocaine and cola, and that, furthermore, because caffeine had been part of the original formula or recipe for the beverage, it could not be legally regarded as an additive. Generous in victory, Coca-Cola voluntarily agreed never to feature any child under twelve in their advertisements, a forbearance they relaxed only in 1986.

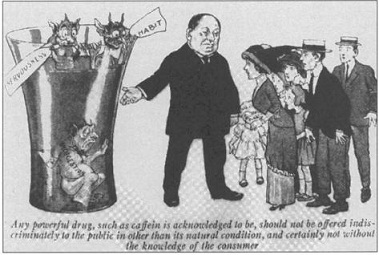

Cartoon of Wiley admonishing an innocent public about the evil goblins lurking unseen in a glass of Coca-Cola. (Good Housekeeping, 1912)

Wiley did not give up. He used the publicity from the case to try to push through provisions adding caffeine to the federal list of habit-forming and harmful substances that must be named on product labels. Still shy of promoting the presence of caffeine in their products, Coca-Cola successfully fought the amendments.

Meanwhile the government successfully appealed the District Court’s ruling to the Supreme Court. It was now determined that caffeine was an added ingredient after all, and the case was remanded to Judge Sanford for retrial on the issue of caffeine’s safety. This time the case was settled out of court, and Coca-Cola agreed to cut the amount of caffeine in its soft drink by half. In return there was an unwritten accord that the Bureau of Chemistry, by then operating under new leadership, would, from then on, leave Coca-Cola in peace.

Coca-Cola has not relied on that ancient truce to protect its interests from those meddlers, newborn in every generation, who would use the law to control what ostensibly free adult citizens are allowed to eat or drink. In the 1970s, largely as a response to reformational grumblings stirred up by concern over an unsubstantiated link between caffeine and pancreatic cancer, Coca-Cola and other purveyors of dietary caffeine set up and funded the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) and its public relations arm, the International Food Information Council (IFIC), both based in Washington, D.C., to help forestall any efforts to regulate or ban caffeine. The heart of these groups was their Caffeine Committee. In the last twenty years ILSI has sponsored and IFIC has publicized dozens of reputable research projects and international conferences of scientists to evaluate the role of caffeine in human health. Naturally, the Caffeine Committee is careful to search out and support those researchers who see caffeine as a relatively harmless compound and to avoid supporting those who would like to see it removed from the market. Nevertheless, the ILSI studies are good scientific efforts, and their results have made important contributions to the inadequate understanding of caffeine’s pharmacological effects.

Cola as Cultural Icon

“Caffeine is caffeine,” the logician might observe, bringing to bear the powerful insight of sovereign reason. Yet with respect to caffeine, coffee and tea, its major natural sources, differ in at least one important way from caffeinated colas and other caffeinated soft drinks, to which caffeine has been added: Coffee and tea are primarily the drinks of adults, while soft drinks, as Wiley admonished, are as commonly or more commonly consumed by children, even small children.

It is strange to say, but the twentieth century, the time of unmatched enlightenment in education and medical science, has witnessed the first widespread acceptance of the general and unmonitored use of a psychoactive stimulant drug by the juvenile population. In fact, except for khat, widely used by adolescent Yemenis, we know of no other mood-altering drug whose use anywhere by the young is or has been not only legal, but approved and fostered by adults.

Sundblom Santa advertisement for Coca-Cola. This is one of many Sundblom paintings that created the American icon of Santa Claus. The fat, red-nosed, red-cloaked, jolly Coca-Cola-drinking version of Santa Clause became a defining image of American cultural life.

Coca-Cola, the forerunner of all commercially caffeinated soft drinks, was, during its first years, an elixir sold in pharmacies. After the turn of the century, the CocaCola Company had to make a choice as to whether to continue promoting the drink as a tonic, which might suggest it was a strong stimulant with a limited application, or to advertise it as a simple beverage, suitable for everyone, including children. Some Coca-Cola leaders had reservations about the latter strategy, partly because they were concerned over the potential danger to children. However, the simple beverage theory won, even though it meant sacrificing any claim, in the words of executive correspondence, for “excellency or special merit,” and Coca-Cola faced the future as one of many soft drinks.

With this strategy in place, it remained for the company leaders to ensure their product a distinctive place in the arcana of common soda fountain options. One of their central problems remained how to inveigle children into becoming lifelong Coca-Cola drinkers while observing their pledge never to show a child under the age of twelve in an advertisement. While the advertising of Coca-Cola is an epic tale, no single feature stands out as clearly or has had such a broad impact on popular culture as Coca-Cola’s most brilliant response to this apparent dilemma: the invention of the modern Santa Claus.

Santa Claus, as we all know, is a portly, white-haired gentleman with a snowy beard, broad smile, rosy cheeks, red nose, wearing a costume somewhat resembling bright red flannel underwear with a broad belt and big black boots, happily busy with the delivery of toys on snowy Christmas Eves. What many may not realize is that this image of Santa is an American, twentieth-century invention, created by Haddon Sundblom, a Swedish artist in the employ of Coca-Cola, and promoted relentlessly into the apotheosis of a folk hero. Before Sundblom’s work, Santa Claus was represented in a variety of ways. In Europe he had traditionally been a serious, even severe, tall, thin man wearing any of the primary colors. In the popular recitation piece “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” written by Clement Moore, a Columbia University professor, in the 1920s, Santa became a jolly elf only a few inches high.

In their book Dream of Santa, Charles and Taylor relate how in 1931, posing his friend Lou Prentice, a retired salesman, as his first model, Sundblom painted the first depiction of the Santa Claus we know in America today. After Prentice’s death, Sundblom used himself as a model, refining his creation further. The Coca-Cola Company built a small advertising industry around Sundblom’s Coke-guzzling saint, who was invariably aided in completing his eleemosynary labors by the lift provided by sugar and caffeine—an advertising effort aimed, obviously, primarily at young children who would, in the course of things, grow into succeeding generations of CocaCola consumers. New Sundblom productions were used on billboards and in magazine advertisements year after year, until his last two paintings were completed in 1964.

The Buzz Beyond: Supercolas and Other High-Dose Caffeinated Soft Drinks

In February 1996, Beverage Marketing Corporation, which offers consulting and information services to the global beverage industries, reported that Coca-Cola Classic was the best-selling soft drink in America, followed by Pepsi-Cola, Diet Coke, Dr Pepper, Mountain Dew, Diet Pepsi, Sprite, 7-UP, Caffeine Free Diet Coke, and Caffeine Free Diet Pepsi.10 Insiders in the soft drink industry and outsiders trying to get in have noticed that the top six brands have one thing in common: They all contain caffeine. Following the maxim “If a little is good, then a lot is better,” a number of companies have offered or are preparing to offer some soft drinks containing more caffeine and others in which the presence of caffeine is a more emphatic component of their market identity.

The first of these high-caffeine soft drinks was Jolt Cola. In a brief company history posted on the Internet, called “Where did Jolt Come From?,” Jolt represents its founder, C.J.Rapp, as a pioneer. In 1985, when Jolt Cola was introduced, their story runs, most beverage companies were pushing a “less is more” approach to new products: fewer calories, less sugar, and less caffeine. Rapp had the vision to buck this trend and put the slogan “Twice the Caffeine” on every bottle and can. What they don’t mention in this article is that Jolt originally boasted “Twice the Sugar” as well. But even though more caffeine might seem to call for more sugar to counteract the increased bitterness, Jolt today has trimmed its sugar to standard levels, but kept the caffeine content as high as ever, which gives the drink a disrinctive “bite” that some people find pleasant.

Rapp says that his product was inspired by college students who were “concocting elixirs to help them study for exams,” perhaps a veiled reference to the use of methamphetamine, dexamphetamine, and caffeine pills. He sees a tie-in between Jolt’s success and the renaissance in coffeehouse culture: “Just as coffee bars began showing up in every city from Boston to Seattle, Jolt, the espresso of colas, took the soft drink market by storm.”

In the 1990s many new high-caffeine soft drinks are flooding the market worldwide. The triumph of Jolt is perhaps more apparent in Rapp’s mind than in the marketplace, as evidenced by the fact that most comments about the product consist of people asking each other if it is still being made and if so where it can be found. Recently we found a grocer in Philadelphia who stocked it. But on returning several weeks later, it was gone, and the owner explained that the distributor was not expected for an indeterminate period.

Another way of looking at it, however, is that, difficult to find as Jolt may have become, people still remember it and seek it out. There can be no doubt that highcaffeine soft drinks can have a distinctive flavor. Jolt itself is a superior product and easily the best-tasting cola on the market. The extra caffeine gives it “point,” a word used to designate piquant bitterness, such as that which is vital to fine coffee’s appeal. Significantly, Jolt, unlike Coca-Cola or Pepsi, is still sweetened with cane sugar, and the clarity of cane sugar, which is far less cloying than cheap corn syrup substitutes, combines with the additional caffeine to create a bittersweet flavor that is hard to beat.

The cola nut is not the source of either the flavoring for or the caffeine content of cola soft drinks. However, other carbonated caffeinated beverages, such as some made from the guarana berry, actually depend for their flavor and stimulant power on the high caffeine content of the fruit or nut itself.

Brazilians consume more than six billion quarts of soft drinks a year, making Brazil the third-largest soft drink market in the world, after Mexico and the United States, and guarana-based drinks make up 25 percent of this market. Antarctica, a local company, and Coca-Cola currently sell the brands that dominate guarana beverage sales, but PepsiCo has announced plans to take them on with a new line of drinks flavored with plain guarana and guarana mixed with peach, passion fruit, and acerola, a citrus-flavored Brazilian berry. Pepsi is also test marketing a guarana drink in the United States called “Josta,” for which guarana is the primary flavor and source of caffeine.

In the late 1990s a new soft drink was created by Steve Gariepy to advance his ambition to market guarana, which he describes as a natural energy source. He hits every questionable note, from vulgarity, pandering to children’s interest in drugs, false historical puffing, and scientific misinformation:

Whatever your reaction may be to the name, you won’t forget it, and you certainly won’t forget the effect this drink will have on you!

…GUTS is geared toward consumers from ages 12 to 24, but it will appeal to anyone who is interested in tapping into a natural energy source. The main flavor of this amber-colored drink is the Paulina Cupana fruit, also known as Guarana, praised by the Andiraze aboriginals of Brazil for thousands of years as a stimulant on both mind and body. Today, Guarana is one of the most sought-after ingredients in “smart drinks,” a new category of beverages consumed by youth at “Rave parties” (drug and alcohol free) all across North America. The Guarana berry has 2.5 times the caffeine per ounce as coffee, giving GUTS almost twice the jolt as a regular cola. Pepsi, for example, has 3.2 mg of caffeine per fluid ounce, compared to GUTS that has almost double that amount. The fruit extract is 100% organic, which places GUTS in the burgeoning category of “New Age” beverages.

Note that if GUTS has twice the correctly stated 3.2 mg per ounce caffeine content of Pepsi, it would have only about a third the caffeine per ounce of average coffee. The drink may be “New Age,” but the snake oil sales tactics are as ancient as the imaginary Andiraze Indians are supposed to have been by the author of this release.11

An interesting phenomenon is the Austrian dominance in the production and consumption of European high-caffeine “energy drinks,” including Red Bull, Blue Sow, Dark Dog, and Flying Horse, to name a few. Austrians, often stereotyped as slow moving and hypochondriacal, consume more than one-third of such beverages produced in Europe. Red Bull, for example, sold 150 million cans in 1996, more than a third in Austria alone.

The use of colas, especially trendy high-caffeine soft drinks such as Kick, Nitro Cola, Semtex, GUTS, Afri-Cola, and the old, original Jolt Cola, are enjoying a kind of cult upsurge among computer programmers. The reason was explained in a recent article by David Ramsey in MacWEEK responding to a reader’s query, “Why do programmers drink so much cola?”12 Some of the answers to this question are discussed in chapter 16, “Thinking Over Caffeine.”

President and Mrs. Clinton gulping Coca-Cola straight from the bottle during a visit to the Moscow Coca-Cola plant, May 1995. (Reuters/ Jim Bourg/Archive Photos)

The biggest news in the area of highly caffeinated soft drinks is the entry of the giant Coca-Cola Company into the $4-billion-a-year “heavy citrus” soft drink market, 80 percent of which currently belongs to Mountain Dew, with the brand Surge. The specter of Wiley’s concerns about the propriety of selling caffeinated soft drinks to young consumers arises in connection with this highly spiked drink, because the company intends to market this high-caffeine, high-calorie beverage to twelve- to thirtyfour-year-olds, especially boys and men. The first television advertisement for Surge was aired during the 1997 Super Bowl. The marketing of Surge marks the first time caffeine itself has been brought to center stage by the manufacturer of a comestible product with a large international market. To a certain extent, what constitutes a highcaffeine soft drink is in the mind of the regulator. Consider that while Mountain Dew is an ordinary soft drink in the United States, it is too supercharged with caffeine to be legally sold on the British market.

The Straight Dope: Vivarin, NoDoz, and Other Caffeine Pills

As the purveyors of caffeine indefatigably repeat, caffeine is the only alertness aid approved for sale by the FDA. This means that companies like SmithKline Beecham, the makers of Vivarin, the largest-selling caffeine pill, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, the makers of NoDoz, and their competitors are in the enviable yet problematic position of being the legal producers and sellers of one of the only over-thecounter psychoactive stimulant drugs outside the matrix of a food or beverage.

Vivarin, which dominates sales, boasts about two-thirds of an estimated $50 million to $60 million market for caffeine pills that are sold through food, drug, and mass merchandise outlets. Additional, hard-to-track sales not included in this market estimate are made through health food stores, convenience stores, rest stops, and college campuses.

Selling drugs, that is, “drugs” in the sense of compounds that can change your mood or even get you high or addicted, may seem like a great business in many ways. But because of increasing concerns about drug use in general and the health of children in particular, the manufacturers of caffeine pills and tablets face a delicate marketing problem: how to promote the responsible use of their products without ever seeming to promote their use by those under eighteen or the abuse of stimulants by adults.

One of the first things marketers do to solve their problems is to determine the profile of their potential consumers. The makers of Vivarin, after many years of experience, have isolated three distinct groups that are good prospects for their product: college students, truck drivers, and bodybuilders. Accordingly, Vivarin’s marketing efforts primarily target them. Irrespective of which of these three groups to whom any given promotional material is addressed, all the claims made on behalf of Vivarin have this common thread: Caffeine can significantly improve mood, briefly deter fatigue, and improve performance as a consequence of these effects. Noticeably absent are any claims that caffeine can augment specific human physical or mental capacities, such as increasing endurance or improving learning skills. The maker’s cautionary remarks to all three groups are also of a piece: that caffeine is no substitute for sleep and that individual responses vary widely, so each person must learn through experience how caffeine affects him.

Alertness aids containing at least 100 mg of caffeine must feature this FDA warning: “The recommended dose of this product contains about as much caffeine as a cup of coffee. Limit the use of caffeine-containing medications, food, or beverages while taking this product because too much caffeine may cause nervousness, irritability, sleeplessness and occasionally rapid heartbeat.”

The college student staying up all night to complete a term paper or prepare for a final exam is one of the most obvious potential consumers of caffeine pills. Because such claims have not received the official imprimatur of the federal authorities, nowhere do the makers of Vivarin adduce the studies demonstrating that caffeine confers limited but significant improvements in the ability to solve math problems or memorize facts. Instead they say only that caffeine can improve moods, including feelings of confidence, and increase alertness, without serious significant mental or physical side effects, and that it is particularly useful in improving performance during “all-nighters.” Vivarin has also tried to capitalize on the nexus of computers, college students, and caffeine by promoting its own home page on the Internet and offering contests and dating services through online channels.

Although many credible claims have been asserted for caffeine’s ability to increase endurance or strength and also for its power to help the body burn fat faster, Vivarin limits its claims to the power of caffeine to help bodybuilders start their daily workouts with an upbeat attitude. The company’s claims for caffeine’s bodybuilding benefits, again, are limited to “producing greater alertness, heightened concentration, and reduced mental fatigue.”

Researchers also have found that caffeine benefits the third group targeted for Vivarin sales: truck drivers and, to a lesser extent, anyone who needs to be on the road for a long time. Caffeine has been repeatedly shown to improve driver safety by increasing alertness. For example, a 1996 study in the Annals of Internal Medicine that found coffee-drinking nurses to have dramatically lower suicide rate than non-coffeedrinking nurses also found a dramatically lower rate of driving accidents. Because falling asleep at the wheel causes about one hundred thousand accidents every year in the United States, causing about fifteen hundred deaths, Vivarin has made driving alertness a kind of mission. However, the company is careful to include in its promotional material admonitory remarks from the National Sleep Foundation and the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety. They caution that highway hypnosis, the fatigue and drowsiness that frequently results from long hours on the road staring at ribbons of highway, is different from sleep deprivation, although the specific ways in which this should alter our understanding of how to use caffeine are omitted. Another admonition is that caffeine at best can create a temporary boost in alertness and deter fatigue for a short time. When a person becomes seriously sleep deprived, it is impossible to prevent the occurrence of so-called micro-sleeps, or brief naps that last about four or five seconds. At 55 miles an hour, this is the equivalent of 100 yards of unconscious and presumably hazardous progress on the road.

Even in this age of the coffeehouse renaissance, caffeine pills continue to be a significant source of caffeine for Americans. Physically and intellectually, caffeine does seem to be the energy booster of champions.