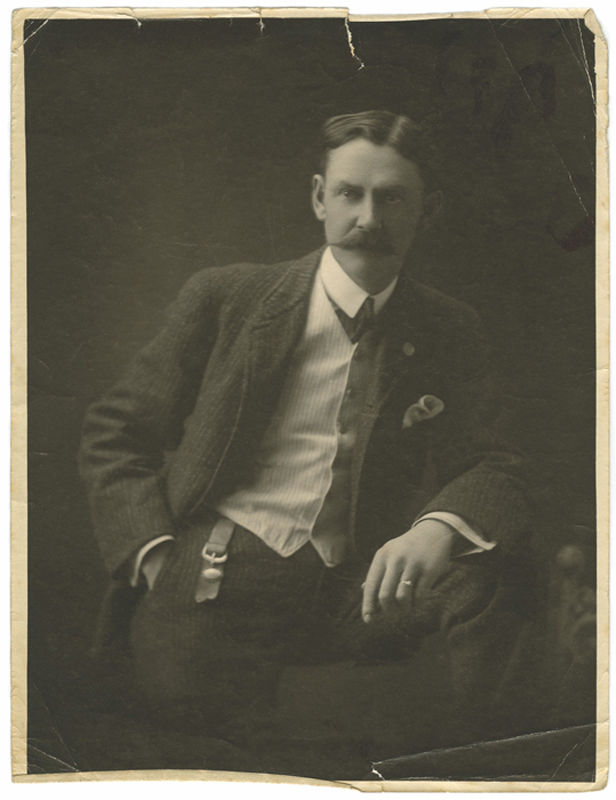

An undated photograph of Shep.

An undated photograph of Shep.

The stories of Otis Shepard’s early life are almost too over-the-top to believe. What was documented in various profiles published during his life and in Otis’s own colorful autobiographical writings is vast—sometimes contradictory, but always entertaining.

Otis was born in 1894 in Smartville, Kansas. His mother, Nancy, was notoriously tough and was said to have killed a Native American who wandered into her kitchen one afternoon. His father, Lucius Franklin Shepard, was either a traveling salesman or a circus performer; his array of unusual skills included specialties in sword swallowing and fire eating. Some accounts claim that Lucius was an expert sprinter, others that he was a fabulous tenor singer or skilled pool player. A 1945 article in Sporting News quotes Otis—or Shep, as he was nicknamed—stating that one of his earliest memories was watching his father “run 45–60 balls to the distress, humiliation, and amazement of some local bumpkin.”1

In 1906, at age twelve, Shep left home, having completed only the fourth grade. He landed in El Paso, Texas, where he briefly worked at the Humphries Photoengraving Shop as an errand boy. “I was privileged to waste paper and ink in a one-man art department,” he later wrote.2 This was likely his first foray into the world of commercial art endeavors. After this, he was an assistant to a scenic artist and became interested in the stage. Then, in the latter part of 1906, he moved to California, settling in Napa Valley, where he worked with his uncle, who maintained vineyards. There, out in the quiet countryside, Shep and four-horse teams hauled wine between small and large wineries. After a year of this hard physical labor, he went south to San Francisco, where he secured jobs in the bubbling media world. Shep worked first at the Oakland Herald Tribune and then at the San Francisco Chronicle, where he became something of a teenage wonder, penning political and sports cartoons under the mentorship of the cartoonist Bud Fisher of Mutt and Jeff fame.

Shep and his mother, Nancy Shepard.

Shep’s astonishing early talent is on display in this drawing, done when he was just eight years old.

Fisher wasn’t the only Bay Area notable Shep encountered. One day, in Oakland, Jack London took young Shep out to the waterfront to give him a lesson in “what life is really like.” London picked a fight with the bartender and got badly beaten. Then, sitting on the curb nursing his wounds, London turned to Shep. “There, that’s what life is really like,” he said.

In 1909 Shep continued his education in drawing and printing by apprenticing for “an old German lithograph artist.”3 But he wasn’t done with the theater. Late 1909 found him with the Bishop Players Stock Company, first working on scenery and then, having been encouraged by the actors, taking the stage himself. He performed with them and also with local barnstorming companies in the area until 1912. His future boss, Charles Duncan, would later tell of Shep’s life during this period for a 1929 profile in Poster magazine:

The itinerant aggregation toured the country in a truck and presented melodramas in which Shep was given old man parts because his boyish voice was changing and had falsetto range. When the truck backed down an incline, demolishing the scenery, that venture was ended. The boy crawled into a freight car containing various sets, props, and one broken-down horse, and when the car was unloaded they took him and the horse out of the scenery.4

After three years of adventures in theater, Shep “hung out . . . [his] shingle”5 as a freelance commercial artist. He spent five years on his own, during which time Duncan later described Shep as having completed “pen-and-ink sketches in a peculiar technique developed by himself—chiefly of furniture.”6 Duncan then hired him first as an artist, and then as art director and general manager of Foster & Kleiser Outdoor Advertising Company.

Lucius Shepard in the early 1900s.

After less than a year in the art department of Foster & Kleiser, working in a realistic, painterly style, Shep, now twenty-four, joined the army’s 115th Pioneer Engineers unit. In 1918 he shipped out from Hoboken, New Jersey, to France to fight in World War I. But Shep always liked a good time, so he didn’t leave without a going-away party and ceremony. Duncan, Shep’s drinking pal Davey Davenport, and various artists and actors went out to Golden Gate Park and buried Shep’s favorite golf club.

Shep the doughboy, sporting a debonair mustache, poses for an official army portrait in 1918.

Though he began with a pick-and-shovel assignment in the army, Shep eventually became the regiment’s official artist. He saw action on three major fronts: Meuse-Argonne, Marbache, and Metz. Through his drawings, Shep recorded everyday life on the ground; he also ascended to the sky by balloon and plane to draw aerial views of the regiments and the battlefields. These drawings were then used for strategic planning purposes. Of course, this was not without danger. One trip was cut short when his plane crash-landed onto a frozen lake. Shep was thrown from the plane and slid across the ice. When he staggered to his feet, his flying jacket tore apart. The back of it had been burned off in the crash. His pilot wasn’t so lucky: he was cut in half at the waist.

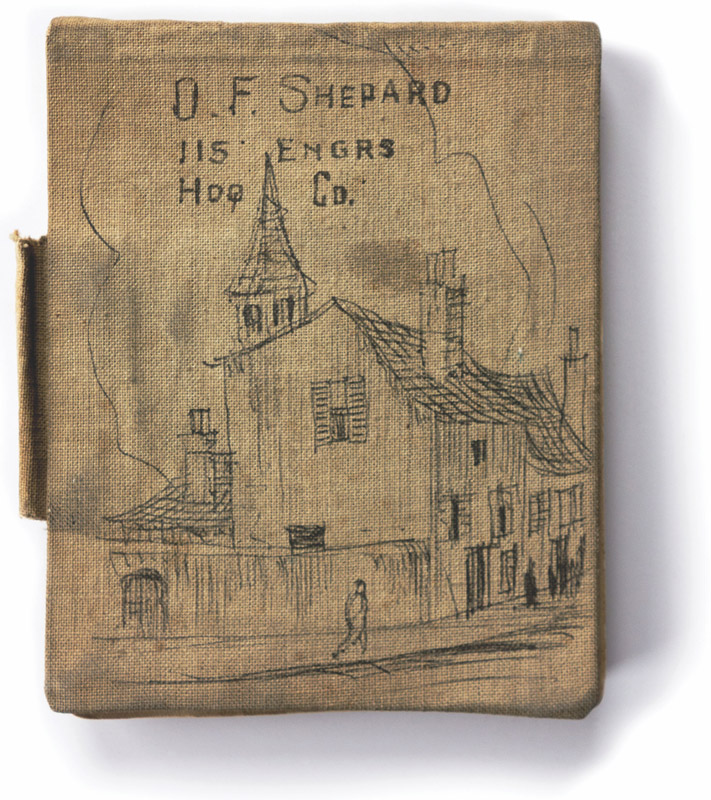

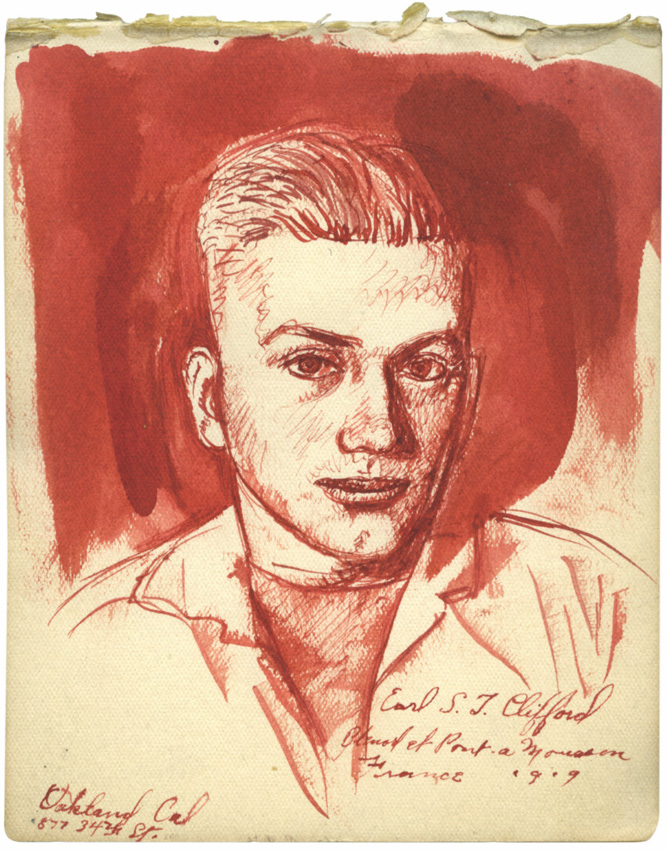

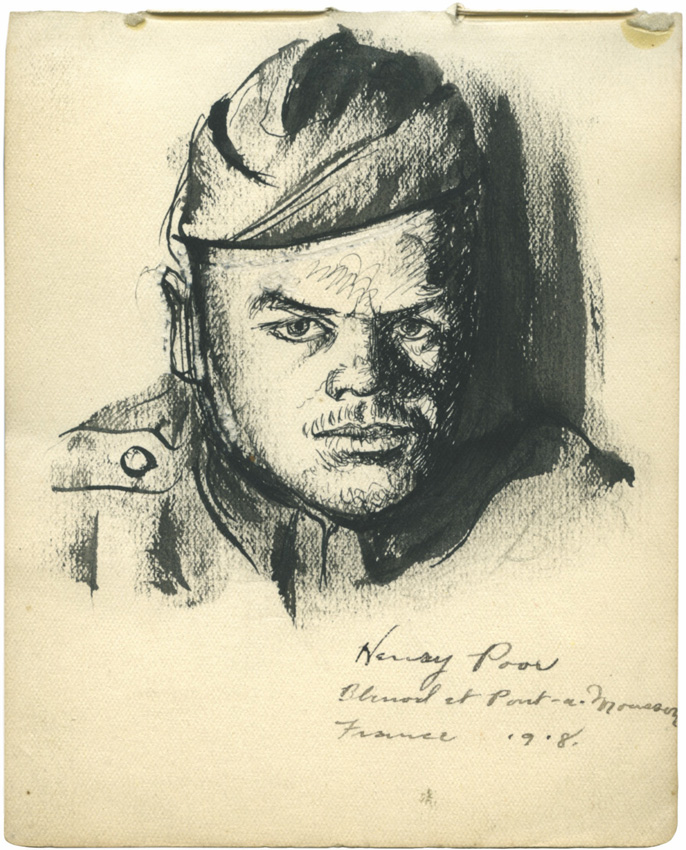

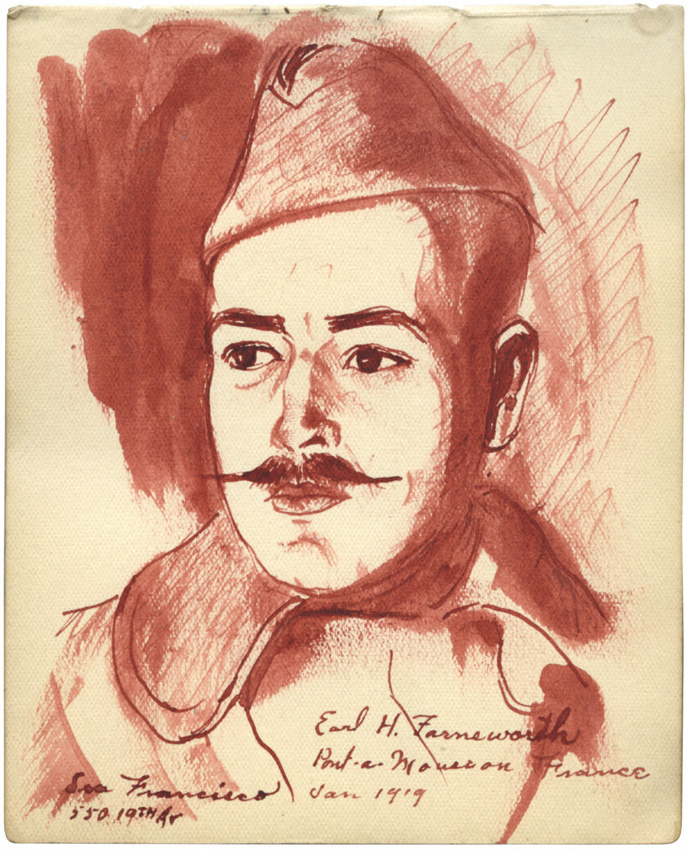

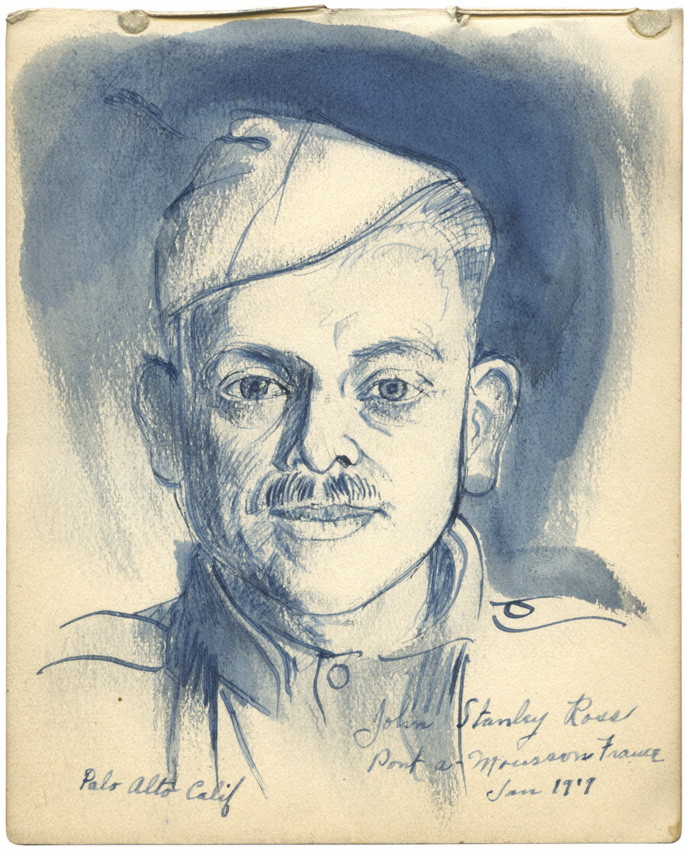

Shep’s 4-by-5-inch sketchbook from his time overseas. In it he drew meticulous portraits of his fellow army engineers (shown below). Though by this time Shep was a professional commercial artist, he had no training, which makes the sensitivity and precision of these pen-and-ink drawings all the more remarkable.

Another time, on a morning sketching jaunt, Shep sat down on a tree stump to draw. As the sun came up, and with it some warmth, Shep and his companions realized that the “morning mist” was actually residual poison gas that had been activated by the sunlight. They’d forgotten their gas masks and they ran from the scene, skin lightly singed.

Shep was injured in the war under somewhat mysterious circumstances. There are two versions of the story: In the version Shep told his children, his colonel ordered him and another soldier to go into a French town that had supposedly been abandoned by the Germans. As the two walked down the main street, a German machine-gunner opened fire. Shep was wounded in the knee and his companion was killed. The story told to Kirk by the colonel, who remained a friend of Shep’s after the war, was that a number of the men in Shep’s unit were of Serbian descent and had a special hatred for their Turkish and German foes. At night, many of them would crawl across the no-combat zone, maneuver into the German trenches, and cut the sleeping German soldiers’ throats. During one such raid, Shep was shot in the knee. For a short time he was reported missing and presumed dead.

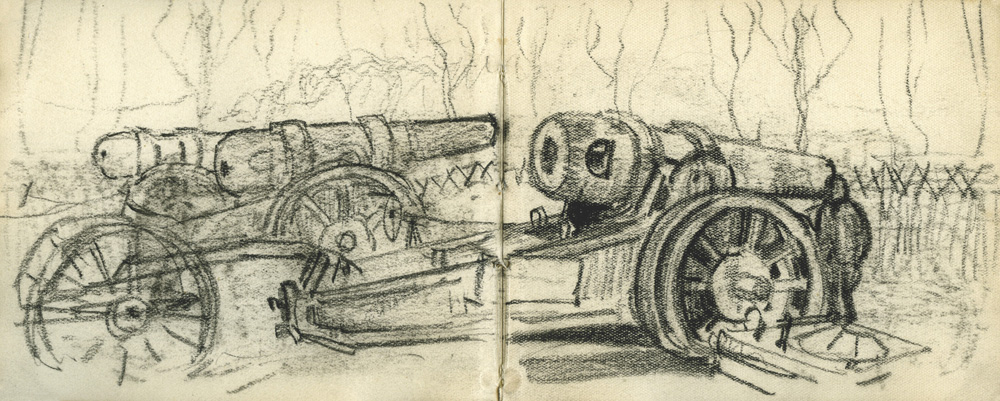

A 1918 drawing of armaments on the battlefield.

A 19-by-25-inch charcoal sketch rapidly done in the field in 1918. The dirigible pictured here was the kind of balloon Shep would have been in when drawing from the air.

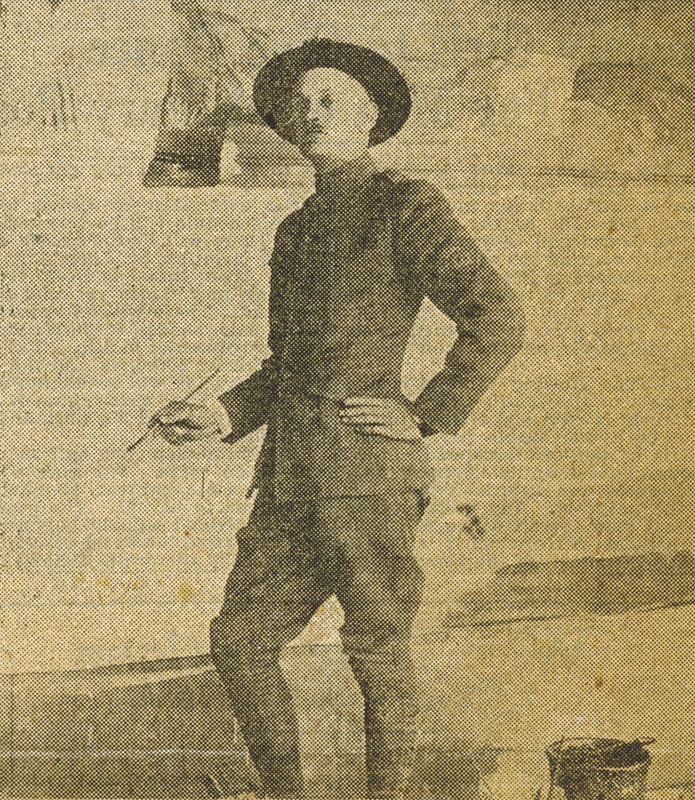

Shep, the regiment artist, in 1918.

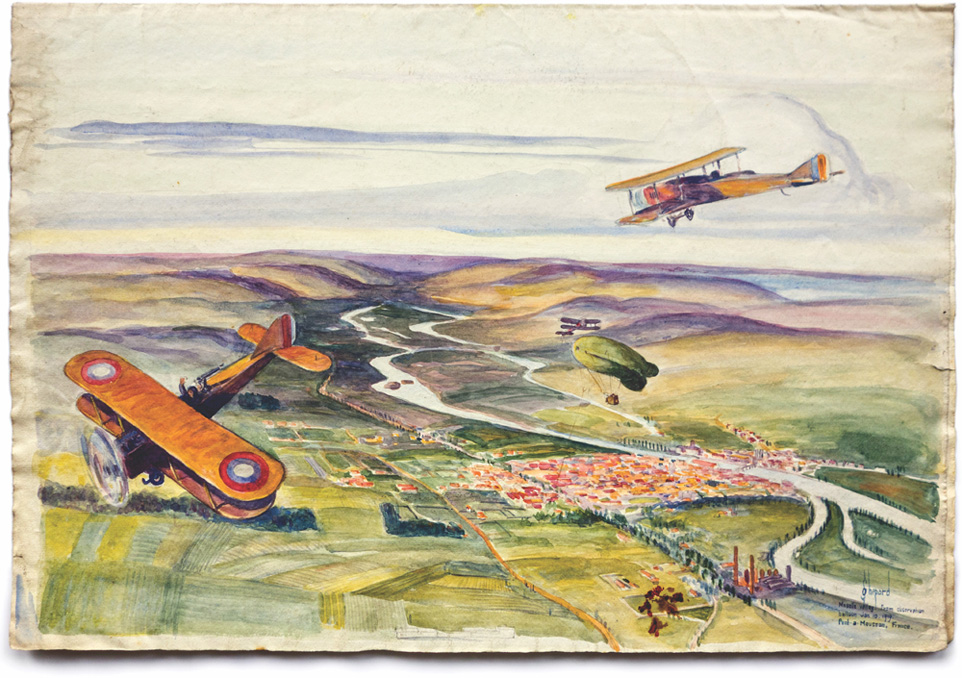

An evocative drawing from the sky typical of Shep’s work during World War I. Shep’s caption reads: “Moselle Valley. From observation balloon Jan 10, 1919. Pont-á-Mousson, France.”

Shep’s haunting watercolor of a crowded train carrying exhausted and wounded troops in 1918.

A serene landscape Shep painted while in Germany in 1919.

Shep wearing wooden clogs and carrying his gas mask and sketch pad, 1918.

After the Allied nations’ 1918 armistice with Germany, Shep renewed his theatrical interests. He organized a “show troop of talent”7 from his own regiment, and in two large trucks they toured American outposts in Europe, even performing before the Grand Duchess of Luxembourg. He also produced at least one poster for the troop. Once that adventure was over, Shep stayed on in Ruhr, Germany, to enjoy the scenery. He used to say that despite it all, he liked the Germans and bore them no ill will, except that his bullet wound screwed up his golf game. When he finally made it back to San Francisco, he ran into Davey Davenport on Market Street, who nearly fainted—“dead” Shep was back among the living.

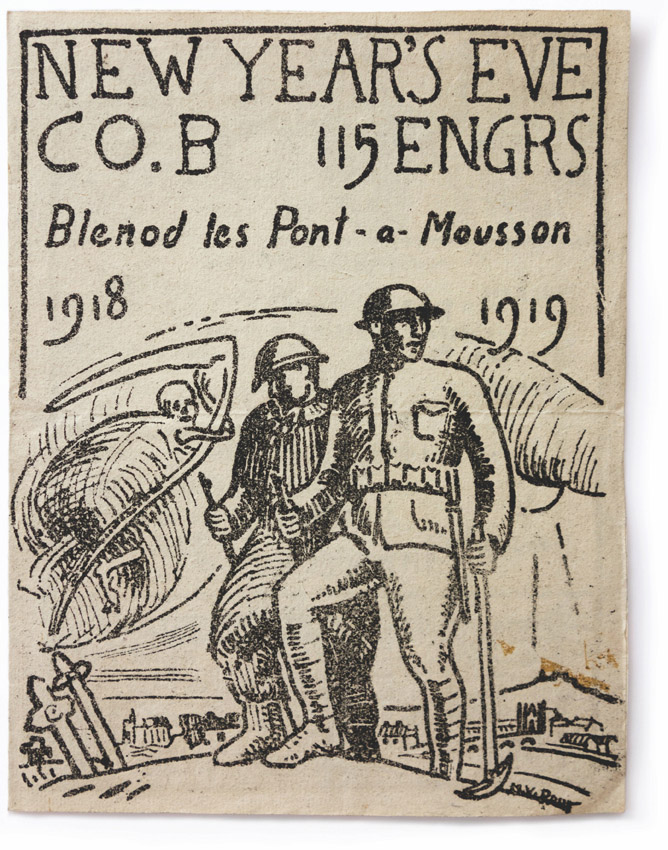

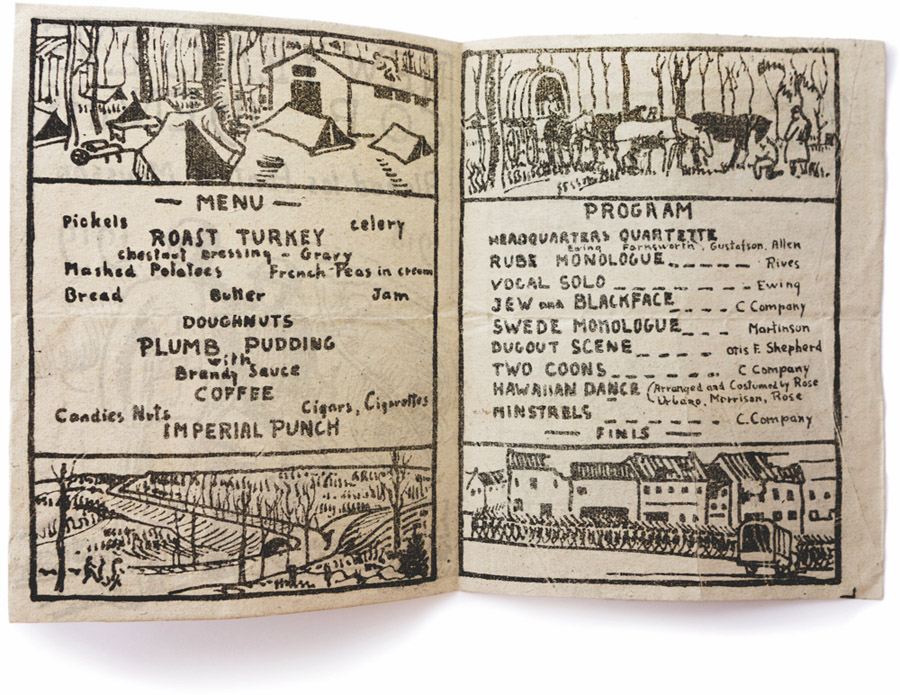

Shep’s program for a New Year’s Eve performance of the variety show he organized. Note Shep’s own contribution: “Dugout Scene.”

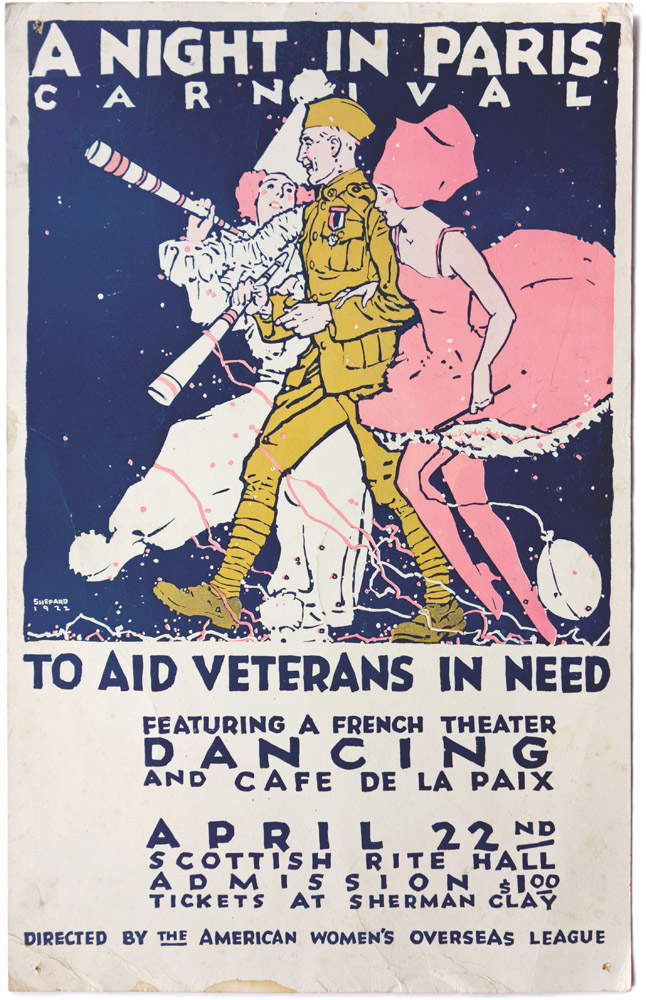

Back in San Francisco in 1922, Shep designed this poster for a benefit carnival for World War I veterans.