Hungry mice, fires, insects and critical judgement have all played their part in the transmission of Scotland’s earliest literature – the work produced in the seven centuries or so before the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath asserted Scottish independence. Sometimes stones have preserved individual words or pieces of poetry, and manuscripts have been guarded with cunning.1 At other times, though, lines of oral or written transmission have come to an end; not just individual works but entire languages have vanished. Parts of Scotland have been settled for over ninety centuries. Beautiful stone monuments such as those of Neolithic Orkney have survived for five millennia, but the earliest extant written materials were produced by immigrants nearly 2000 years ago. From prehistory onwards all communities in Scotland began as immigrant communities. The Roman invasion of mainland Britain brought to the middle of the island not only Mediterranean and Germanic Europeans, but also Syrians and Africans as part of the military forces stationed along Hadrian’s Wall. There they built shrines to Mithras, Ashtoreth, Jupiter and the Roman pantheon of gods, as well as to local deities. As conquerors, they made overtures to the surrounding population. Inscribed documents, wooden tablets of hollowed-out Scots pine filled with wax, were discovered wonderfully preserved in waterlogged pits near Hadrian’s Wall in the 1970s. These include shopping lists, personal letters, and material about a recruitment drive aimed at attracting members of the Anavionenses. Recruiters wanted this tribe, who lived around the River Annan in what is now southern Scotland, to join the Roman army.2

Some of the Roman forces moved northwards up the island, fighting and bribing the tribes of ‘Caledonia’, a Latin name which later came to be applied to what we now call Scotland. In AD 142–3 the Romans erected the Antonine Wall. Built of turf on a sandstone base, it ran for thirty-seven miles between the Firths of Forth and Clyde. Parts of it can still be seen. Never occupied for long, it was designed, like Hadrian’s Wall, not as an absolute barrier but as a series of portals to control the movements of native peoples. This resulted in many kinds of contact between the locals and the incoming forces, who were sometimes from distant parts. We know from stone inscriptions, for instance, that the large, wet and windy Roman fort at Bar Hill near Kilsyth in the Scottish Lowlands was garrisoned by Syrian archers, then by soldiers from the Rhineland. Sometimes the incomers recorded their susceptibility to the place around them. One of five nearby altars erected by a Roman centurion is dedicated ‘GENIO TERRAE BRITANNICAE’ (‘To the Presiding Spirit of the Land of Britain’).3

Inscriptions like this – written by foreign conquerors in their imperial language – are scanty at best. Nothing we could regard as imaginative writing survives from Scotland before the sixth century, though occasionally a short inscription affords a glimpse of the people who passed across the landscape. Standing within the perimeter of Edinburgh airport is the (?fifth-century) Catstone of Kirkliston with its dedication to ‘VETTA’.4 In south-west Scotland, at Whithorn, St Nynia or Ninian (who trained in Gaul) was reputedly part of a very early Scottish Christian community. A local inscription dating from the very late fifth century consists of a monogram made up of the intertwined Greek letters chi and rho (the first two letters of Christ’s name), then some Latin words which can be translated as,

We praise thee, Lord. Latinus, aged 35, and his daughter, aged 4 years, made [this] sign here. [He is the] grandson of Barrovadus.5

These few words by a Romanized Briton are the oldest written record we have of an act of Christian worship in Scotland. Articulated on behalf of both male and female, bringing together three generations, they preserve a moment when father and daughter stood by the Solway Firth. It makes it all the more attractive to know that ‘Barrovadus’ was a British name meaning ‘Mole-Head’.

Drawing on several cultures, and fusing Greek and Latin with native elements, this Christian inscription is a suitable early emblem of polylingual Scottish literature. Christianity and monastic culture nourished the production of most of the early masterpieces of Scotland’s written art. Between them, the Romans and the Christians established Latin as Scotland’s most ancient literary language. There appears to have been vigorous oral composition going on in a rich brew of languages across the terrain of Scotland in this early medieval period, but for much of the Middle Ages hardly anyone other than Church personnel could read or write. As far back as we can go, and throughout Scotland’s literary history, works have been produced in this country in several tongues, sometimes operating independently, at other times influencing one another. Then as now, virtually all these languages have involved a considerable degree of interaction with oral or written literatures outside Scotland. Some, like Latin and in more recent times English, have been written across the known world of their day; others, such as Gaelic or Welsh, have had their closest links with other parts of the British Isles. Scotland’s literary works splendidly and not infrequently celebrate independence; yet even when they do so they also articulate through vocabulary, form, and content kinds of interdependence with many other countries and cultures.

So it should be no surprise that a lot of the early literary works associated with Scotland are written in the international language of Latin. Some of these poems and other written texts were probably produced on Í, better known as Iona, a three-mile-long Hebridean island to which the monk Columba sailed from Ireland in 563, and where he established a monastery. Although in the Middle Ages places accessible by boat were among the most easily reached, getting to Iona still takes time. Today, even after they get to Oban on the West Coast of the Scottish mainland, visitors must take a ferry, then travel thirty miles across the island of Mull to Fionnphort from where they sail over the Sound of Iona. If their timing is good, they step off the lowered bow of the landing craft when a wave has just receded. That way they arrive on Iona with dry feet.

Much of it rebuilt in the 1930s, the modern Iona Abbey is a reconstruction of substantial late medieval stone buildings. Columba’s monastery, with its wooden church, magna domus (communal building), and farmed plots bounded by a 400-metre-long earth rampart, looked very different. Nevertheless, on top of the rocky mound in front of the present-day Abbey’s western facade, archaeologists have unearthed what may well be the base of the small, raised wooden hut or tegorium where Columba worked during the day. Born the cousin of an Irish king, then trained as a monk, he appears to have gone into exile in his early forties, shortly after a battle in 561 which involved his family and their allies. Although Columba made periodic visits to Ireland, it is his activities on Iona where he wrote, worshipped, and guided a community of monks, which made him the most celebrated of Scottish saints. The work of his monastery nurtured a Columban family of other Christian foundations from the nearby island of Tiree to a constellation of Scottish and more distant, continental locations including Salzburg and present-day Switzerland. Even today on the shores of Lake Zurich there are small settlements called Stafa and Iona.

The community Columba founded soon became a substantial centre of literary production. On Iona, long before the invention of printing, manuscripts were copied by hand for study and dissemination. Although its handwritten originals are long lost or dispersed, the monks had a library of manuscript books. They kept these in chests to protect them from the elements and wildlife. There is evidence not just of a thorough knowledge of Latin texts on Iona, but also some interest in Greek lettering and vocabulary. Columba was recalled as powerfully busy, constantly attending to prayer, reading and writing. His example inspired a group of writers, poets and thinkers over several hundred years. An early eighth-century Iona manuscript survives in modern Switzerland, while it has been suggested that the seventh-century Latin text of the Gospels now known as The Book of Durrow was made on the small Hebridean island. The later, more celebrated Book of Kells with its magnificently complex ornamentation was probably begun on late seventh-century Iona, then taken from the island to Kells in Ireland by Columban monks fleeing Viking raiders. This would explain its being described in 1007 as ‘the great Gospel of Colm Cille [Gaelic for Columba], the chief relic of the Western World’.6

Complex and rich in its symbolism, the gospel Book of Kells (now in the Library of Trinity College, Dublin) manifests the Christian Word of God and celebrates that Word’s incarnation in flesh; it sings of the harmonious and diverse divine creation, its illustrations ranging from stylized, thick-bearded saints to rats, cats, proud hens and a cockerel. One of the treasures of early medieval European manuscript culture, the Book of Kells has been described as the world’s most beautiful book and is a two-dimensional counterpart to Iona’s later, splendid carved stone crosses. The exact origins of many of the early works linked to Iona are uncertain, but there is overwhelming evidence for the island as a crucial source for some of Scotland’s first surviving Christian writings. Pre-eminent among these is the Latin poem known by its opening words, ‘Altus prosator’. Magnificently translated by Edwin Morgan in the early 1990s, this is a poem to set beside the Book of Kells. It now stands at the head of several anthologies of Scottish verse.7 Although it possibly dates from the seventh century, modern commentators have regarded its attribution to Columba as defensible.8

The ‘Altus Prosator’ is a rich and intricate hymn of Christian praise. Far older than the great medieval cathedrals of St Andrews or Glasgow, it nevertheless carries their sense of amplitude and awe. An abecedarian poem, its six-line stanzas begin in turn with each of the twenty-four letters, from A to Z, of the Latin alphabet. This work, attuned to the God who is ‘alpha and omega, the beginning and the end’, and to the twenty-four hours that measure the human day, speaks through its form of God’s power over time and space.9 Running from the creation of the universe and the ensuing Fall of Man to the Apocalypse and the final Day of Judgment, it is the product of an imagination richly nourished by that lectio divina (‘holy reading’) recommended to monks by St Augustine and others as a way of attuning the reader to the guiding movement of God’s Holy Word.

Such an internal attunement to scripture can be heard from the poem’s very first line, ‘Altus prosator vetustus dierum et ingenitus’ (‘Ancient exalted seed-scatterer whom time gave no progenitor’). The phrase ‘vetustus dierum’ (‘Ancient of Days’, as the Authorized Version of the Bible has it) comes from a Latin version of the Old Testament Book of Daniel. Throughout the poem revoicings of biblical phrases manifest a union with God’s Word. The acoustic of the ‘Altus Prosator’, its sound-patterning, reinforces a sense of bonding, of unity. Every line is made up of two half-lines of eight syllables, and the conclusion of each half-line rhymes with the end of the whole line, as ‘vetustus’ rhymes with ‘ingenitus’ above. So a sense of divine wholeness persists through this panoptic, alphabet-shaped work, despite its harsh accounts of evil, hellish torments, and demonic battles where ‘aeris spatium constipatur satellitum’ (‘the airy spaces were choked like drains with faeces’). What the poem calls ‘world harmony’ (‘mundi… harmoniam’) is articulated through its own structure. If it praises a God who is a ‘prosator’ (‘seed-scatterer’) and follows His words, then it also partakes of His power in its creation and dissemination of new words in a way that, though less extreme, suggests the ‘Hisperic Latin’ which proliferated in seventh-century Irish Latin poetry, rejoicing in neologisms and strange vocabulary. Highly intellectual when it draws on early Christian authorities such as the fifth-century St John Cassian (born in what is now Romania), or when it relishes Greek-derived lexis, the poem is also very accessibly beautiful to a modern audience, not least in its celebration of God’s power over the world’s climate:

LIGATAS aquas nubibus frequenter cribrat Dominus

ut ne erumpant protinus simul ruptis obicibus

quarum uberioribus venis velut uberibus

pedetentim natantibus telli per tractus istius

gelidis ac ferventibus diversis in temporibus

usquam influunt flumina nunquam deficientia.

Letting the waters be sifted from where the clouds are lifted

the Lord often prevented the flood he once attempted

leaving the conduits utterly full and rich as udders

slowly trickling and panning through the tracts of this planet

freezing if cold was called for warm in the cells of summer

keeping our rivers everywhere running forward for ever.10

Cosmic in its scope, the magnificent ‘Altus Prosator’ goes on to speak of the movements of planets. Its interest is not in empirical astronomy but in seeing how the workings of the universe act as a token of the power and nature of divine order. So the whole cosmos is drawn into this hymn to its Creator.

The ‘Altus Prosator’ is the greatest of the poems associated with early Iona, but is only one of an impressive group of Latin and Gaelic works linked to Columba’s name. Another of these is the Gaelic ‘Amra Choluimb Chille’ (‘Elegy of Columba’) attributed to the Gaelic poet Dallán Forgaill, who flourished around the year 600. The poem announces that it was commissioned by Columba’s cousin Áed, King of Tara in Ireland. Using some Latin vocabulary and many Irish borrowings from Latin, this long, richly alliterative work often rearranges words in a surprising order to celebrate Columba’s guardianship, learning, asceticism and ascent to heaven. The Saint’s death has left the world disconsolate:

Is crot cen chéis,

is cell cen abbaid.

It is a harp without a key,

it is a church without an abbot.11

In the years that followed, a cult of Columba developed, encouraging such fine and adoring Gaelic poems as those attributed to Beccán mac Luigdech. A professionally trained Christian poet from Ireland, he died in 677 and may have lived for a considerable time on the Hebridean island of Rhum. In work such as Beccán’s, Columba is a source of light, a candle, a sun, a bonfire, a flame; but also a tough, heroic wanderer on his peregrinatio, his physical and spiritual journeying. Where the Desert Fathers who so influenced these early Celtic Christians travelled across North African sands, Beccán’s Hebridean Columba in the ‘Tiugraind Beccáin’ (‘Last Verses of Beccán’) voyages over rough and changeable seas:

Cechaing tonnaig, tresaig magain, mongaig, rónaig,

roluind, mbedcaig, mbruichrich, mbarrfind, faílid, mbrónaig.

He crossed the wave-strewn wild region, foam-flecked, seal-filled,

savage, bounding, seething, white-tipped, pleasing, doleful.12

In the body of poems associated with Iona, not only are there many links with the ancient poetry of Ireland, but there is also a sense at times of the mutual interlacing of Gaelic and Latin. The modern Gaelic scholar John Lorne Campbell has called attention to Scottish Gaelic verse ‘conventions inherited from Middle Irish and based ultimately upon early medieval Latin hymn poetry’.13 Sometimes Gaelic may have influenced Scottish Latin. Certainly work in both languages is attributed to several of the Columban poets. One of these poets is Cú Chuimne (‘Hound of Memory’), a learned Iona monk who, with an Irish colleague, compiled the Collectio Canonum Hibernensis, an influential anthology of rules for the religious life. Cú Chuimne’s Latin hymn to Our Lady makes use of distinctively Irish kinds of aicill or binding rhymes where the sound at the end of one line is echoed during the course of the next; the same poem of praise to the Virgin also employs the ornamental alliteration which characterized poetry in Irish Gaelic. In their elaborate loopings and interweavings, Iona’s manuscript interlacings and later carved stone crosses are a visual counterpart to these poems with their elaborate binding together of sounds.

The Iona crosses preserve some of the earliest icons of Mary in the British Isles. Apparently written for choral singing, the thirteen stanzas of Cú Chuimne’s hymn to the Virgin bond together a religious community of voices as part of a larger ritual which, like rhyme itself, sounds a division in order to proclaim a unity:

Bis per chorum hinc et inde

collaudemus Mariam

ut vox pulset omnem aurem

per laudem vicariam.

Through two-part chorus, side to side

let our praise to Mary go,

so every ear hears our praise voiced

alternating to and fro.14

Praise of the divine, of religious leaders or of heroic secular lords is the great motivation of most of the early poetry associated with early medieval Scotland. As explained in the Introduction to the present book, across the area we today designate ‘Scotland’ at least five languages were spoken in the early medieval period. In the surviving literature praise predominates, whether the work is composed in Latin, in Gaelic, in Welsh (which was once spoken in southern areas), or in the distinctive form of Old English used in that Kingdom of Northumbria whose territory included parts of the area now known as the Scottish Borders and extended as far as the Forth.

Praise is also important in the early prose written by monks to glorify God and His saints. Prominent here is the learned Adomnán, ninth Abbot of Iona, who was born in Ireland around 628 and died on Iona in 704. Adomnán is remembered as a great Gaelic legislator. Heinitiated that Irish Cáin Adomnáin (Adomnán’s Law) which protects noncombatants and asserts their rights. Its preamble, written later, calls it ‘the first law in heaven and on earth which was arranged for women’.15 During the 680s Adomnán also wrote in Latin his De Locis Sanctis (About the Holy Places), a sacred travelogue offering detailed accounts of biblical sites. He had never visited these, but his text is presented as drawing on the eye-witness testimony of the Gaulish Bishop Arculf, whose ship has been blown off course to the western coast of Britain. Adomnán seeks to use Arculf’s descriptions to enrich the reading of scripture, explaining how the world articulates God’s glory, and how apparently diverging accounts actually ‘speak together in harmony’.16 Rich in biblical and liturgical phrasing, this theological work was later abridged by the Venerable Bede in England. Like the ‘Altus Prosator’, it is a product of much ‘holy reading’.

It is a testimony to the intellectual achievements of Adomnán’s far western community that, for all its remoteness, it generated such a commentary on Jerusalem. A similar reflection resounds at the culmination of Adomnán’s most substantial work, the Vita Columbae, his account of his kinsman Columba’s life. This was written on Iona in the 690s, by which time the island had a considerable influence on culture elsewhere in Scotland. The ninth abbot, who clearly considers himself an Irishman, delights that, although the earlier saint

lived in this small and remote island of the Britannic ocean, he merited that his name should not only be illustriously renowned throughout our Ireland, and throughout Britain, the greatest of all the islands of the whole world; but that it should reach even as far as three-cornered Spain, and Gaul, and Italy situated beyond the Pennine Alps; also the Roman city itself, which is the chief of all cities.

The three sections of this Life seek to demonstrate Columba’s power and blessedness through accounts of his prophetic insight, his powerful miracles and his engagement with angelic visions. All these are fused with details of monastic life on Iona – singing, reading, writing, building barns, transporting milk. Although the island at this time appears to have been an all-male community, Columba is presented as sharing and validating Adomnán’s concern with the protection of women.

The Vita Columbae manifests a political imagination. It is designed to bolster the strength of the developing Columban family of monasteries, not least on the north-eastern Scottish mainland. There Columba’s miraculous powers defeat Pictish magicians. His prayers also subdue ‘a certain water beast’ lurking in the depths of the River Ness which suddenly surfaced ‘with gaping mouth and with great roaring’. From this, the first written account of the Loch Ness Monster, to Adomnán’s story of Columba expelling a devil from a milk churn, the Vita Columbae is full of engaging narratives and vignettes. It is also a didactic work which demonstrates its saint as strong, often austere, and purposefully unbending. Writing with engagement and emblematic vigour, Adomnán aims not to make Iona a place of pilgrimage but to enhance its ecclesiastical power and to portray a spiritual leader who knew and embodied ‘the fear of God’. While the name Iona arises from a misreading of the Latin phrase ‘Ioua insula’ – the Í-ish island – Adomnán explains that it is divine patterning which gives this saint the name Columba (which, like the Hebrew word ‘Iona’, means ‘Dove’), linking him to the emblem of the Holy Spirit. Like the ‘Altus Prosator’, the Vita Columbae speaks of terror and danger, yet also carries a sense of enduring lyrical beauty, as when Iona’s monks, returning across the middle of the island ‘towards the monastery in the evening after their work on the harvest’, all sense ‘a fragrant smell, of marvellous sweetness, as of all flowers combined into one’, and realize slowly that it is Columba, coming ‘not… in the body to meet us’, but sending his spirit to refresh the harvesters as they walk.17

As well as this Latin prose, Adomnán may have written verse in Gaelic. It was his native language, but he maintained that others throughout the Latin-reading world might consider Gaelic a poor (‘uilis’) tongue.18 His account of Iona makes it clear that the Columban community contained people who would have spoken several other languages, including Pictish and Old English, though no literature in these tongues is mentioned. Latin was the language of the Church, but the vernacular speech of the kingdom whose ruler granted Iona to the monks, Dál Riata, was what is now called in Ireland Irish and in Scotland Gaelic. Dál Riata was a northern Irish kingdom which had expanded across the sea to western Scotland. When Adomnán writes of ‘nostram Scotiam’ he means ‘our Ireland’. Only centuries later did the word ‘Scotia’ come to be used of the northern part of the British mainland. Adomnán and the Columban tradition remind us just how Irish are the early surviving literary works of the country we now know as Scotland.

Although the geological outline of the islands of Britain and Ireland has remained virtually unchanged throughout historical time, the tribal territories, kingdoms and national identities projected on to the terrain have altered considerably. It is the nature of such identities to be dynamic, reconfiguring over the years. So, if seventh-century Dál Riata spanned the Irish Sea, then seventh-century Northumbrian power encompassed what is now Dumfriesshire and Galloway. At Ruthwell in modern Dumfriesshire are preserved the earliest surviving parts of a version of the untitled poem known from Victorian times as ‘The Dream of the Rood’. This ‘Vision of the Cross’ is written in a Germanic language which we call Anglo-Saxon or Old English, and which would later evolve into both the English and Scots tongues. Although the poem’s rather German-sounding language is far removed from modern Scots or English, it contains some words which today’s readers may recognize: the dreamer, for instance, dreams ‘to midre nihte’ (after midnight) about a marvellous ‘treow’ (tree). The full Old English text is reprinted with a facing modern English translation in The Penguin Book of Scottish Verse.

At Ruthwell sections of four extracts from this ancient poem survive incised in runes on a magnificent carved stone cross. The cross also carries Latin quotations from the Gospels and from accounts of early Christian saints; some of these are identifiable, others shattered or eroded. So, for instance, above the relief carving of John the Baptist holding up the Lamb of God only one word can be read: ‘… ADORAMUS…’ (… we praise…). The figurative and decorative carvings clearly allude not only to other biblical texts such as Christ’s declaration ‘I am the true vine’, but also to older, pagan emblems like the Tree of Life in Germanic mythology. In this way the Ruthwell Cross bonds Christianity to older native religious traditions. Its focus on a tree allows it to tap into pre-Christian resonances at the same time as expressing an orthodox Christian viewpoint in a remarkable way that mixes allegory with impassioned personal testimony. It is possible that this cross may once have carried as many as fifty lines of the poem associated with it. The four preserved extracts all come from the middle of ‘The Dream of the Rood’ as that poem survives in its most expanded version, found in a tenth-century manuscript now in the Cathedral Library at Vercelli, northern Italy. The Ruthwell Cross has been called a ‘lapidary edition’ of the poem, and its existence probably implies that the local audience had knowledge of a larger work from which these extracts were quoted.19 While part of the Vercelli Book’s text may be a later addition, the northern character of its language marks it out as Northumbrian, and the Ruthwell Cross gives this poem a strong connection with the land we now call Scotland.

Written in the alliterative verse of Old English poetry, in which each line is divided into two halves, each containing (usually) two stressed syllables, the work begins in the early hours of a morning when the speaker dreams a great dream, seeing a huge, scarred, jewelled ‘tree of glory’ shining like a beacon in the sky ‘on lyft laedan leohte bewunden’ (held high in heaven, haloed with light). The word ‘cross’ (‘rode’) is not mentioned until well into the poem, giving the work a hint of almost riddling allure. However, as my modern English version suggests, it becomes evident as the poem develops just what lies at its heart.

I lay a long time, anxiously looking

At the Saviour’s tree, till that best of branches

Suddenly started to speak:

‘Years, years ago, I remember it yet,

They cut me down at the edge of a copse,

Wrenched, uprooted me. Devils removed me,

Put me on show as their jailbirds’ gibbet.

Men shouldered me, shifted me, set me up

Fixed on a hill where foes enough fastened me.

I looked on the Lord then, Man of mankind,

In his hero’s hurry to climb high upon me.

I dared not go against God’s word,

Bow down or break, although I saw

Earth’s surface shaking. I could have flattened

All of those fiends; instead, I stood still.

Then the young hero who was King of Heaven,

Strong and steadfast stripped for battle,

Climbed the high gallows, his constant courage

Clear in his mission to redeem mankind.20

Presenting Christ as a ‘young hero’, the poem draws on secular ideas of the Lord as warrior and protector, but some of its power comes also from the brilliantly imagined talking tree which is forced to share, yet also accepts, Christ’s suffering. Violently united with the Son of God as the nails are driven in, the wooden cross is then ‘dumped in a deep pit’ after the Crucifixion. After its ordeal, the holy tree ascends to heaven as a shining cross with the power to heal all who fear it in faith. It speaks of the heavenly glories that await believers in the hall of their Lord. With its richly measured visionary brilliance, this is a magnificent poem. It tells of intense suffering, but also of triumph and praise.

As the crow flies, the ‘ADORAMUS’ of the Ruthwell Cross is about forty miles north-east of the stone recording the praise offered up by Latinus and his four-year-old daughter at Whithorn two centuries earlier. The name Whithorn is an Old English one meaning ‘white house’ (a reference to St Nynia’s church there); the name ‘Ruthwell’ probably means ‘well of pity’. Both attest to the Northumbrian Christian presence in this area, one strongly connected to the heroic and visionary literature of that kingdom. The Northumbrian Bede would praise both Nynia and Columba in his Latin History of the English Church and People (written in 731), and Latin poems in praise of Nynia may also date from the same period.

In the early seventh century the Northumbrians had expanded their territory northwards as far as the Forth, and had come into conflict with the people of Dál Riata. Adomnán went to central Northumbria in the 680s. There he studied the practices of Anglian monks and secured the release of Irish prisoners. In 685 Northumbria’s King Ecgfrith led his armies north into Pictish territory, but the Pictish victory at Nechtansmere or Dunechtan, now Dunnichen, near Forfar in eastern Scotland, resulted in the death of Ecgfrith and many of his men. The Northumbrian Angles were driven south, making possible the eventual establishment of a Scottish nation. Such recurring bloody conflicts over several hundred years in this early ‘Dark Age’ period had literary consequences, nourishing poems in praise of military, rather than spiritual, heroes.

Greatest among these poems is the Welsh-language The Gododdin, which celebrates in complexly rhyming syllabic metre an attack made around the year 600 by a northern war-band, the Gododdin, from Din-Eidin (Edinburgh) against a southern enemy force at Catraeth – Catterick in modern Yorkshire. Comprising a cluster of elegies praising heroes who fell in the battle, and existing in two incomplete texts, The Gododdin has been called ‘the oldest Scottish poem’, though it seems to postdate the ‘Altus Prosator’ and survives in a thirteenth-century Welsh manuscript.21 At the core of this substantial work is archaic material attributed to the poet ‘Aneirin’ who is said to have lived in the second half of the sixth century. Composed for oral bardic recitation, but perhaps written down in the eighth century, it appears to have been transmitted though the Welsh-speaking Kingdom of the Britons in Strathclyde (Strat Clut) which withstood the encroaching Angles in the sixth and seventh centuries. A fragment interpolated into the Gododdin manuscripts celebrates the victory of the Strathclyde Britons from Dumbarton in 642 against the ruler of Dál Riata; he is left slaughtered, his corpse’s head pecked by crows. Like ‘The Dream of the Rood’, but in an almost completely secular context, The Gododdin (which contains one of the earliest mentions of King Arthur) tells repeatedly in woven, musical language of the sacrificial suffering of a heroic lord:

Mynog Gododdin traethiannor;

Mynog am ran cwyniador.

Rhag Eidyn, arial fflam, nid argor.

Ef dodes ei ddilys yng nghynnor;

Ef dodes rhag trin tewddor.

Yn arial ar ddywal disgynnwys.

Can llewes, porthes mawrbwys.

Os osgordd Fynyddog ni ddiangwys

Namyn un, arf amddiffryt, amddiffwys.

A lord of Gododdin will be praised in song;

A lordly patron will be lamented.

Before Eidyn, fierce flame, he will not return.

He set his picked men in the vanguard;

He set out a stronghold at the front.

In full force he attacked a fierce foe.

Since he feasted, he bore great hardship.

Of Mynyddawg’s war-band none escaped

Save one, blade-brandishing, dreadful.22

Relentlessly, movingly elegiac in its account of the warriors of the Gododdin, that tribe which the Romans had called Votadini, The Gododdin is not a narrative poem but a gathering of laments, sometimes dealing with individual named heroes, and at other times with the whole war-band. On their thickmaned stallions, with blue blades flashing over gold-bordered clothing, these gold-torqued, ferocious comrades charge before the reader in terms of splendid praise. Riding far from their down pillows, mead and drinking halls, they gallop towards violent extinction.

The Gododdin exalts military masculinity, courage, lordly generosity. It makes use of repeated heroic understatement. Confusion surrounding the surviving texts only adds to a sense of that heroic swirl which gives the poems a cumulative elegiac power. While the constant use of proper names propels hero after loyal hero into the foreground, hymning largesse and prowess in battle, the omnipresent past tense of lamentation relegates every man to an irretrievable past:

Iôr ysbâr llary, iôr molud,

Mynud môr, göwn ei eisyllud,

Göwn i Geraint, hael fynog oeddud.

Glorious lord of the spear, praiseworthy lord,

The sea’s benevolence, I know its nature,

I know Geraint; you were a bountiful prince.23

The sense of loss so strikingly present in The Gododdin is shared with the Welsh Urien cycle of poems which, with their memorable lament over a severed head and a nettle-strewn hearth, record the bloody conflicts and mid-sixth-century collapse of Urien’s earlier Kingdom of Rheghed or Reget around the Solway Firth. Alluring among the interpolated materials found in The Gododdin manuscript is the short Welsh-language poem known as ‘Dinogad’s Coat’, which is presented as sung to a little boy whose father has gone hunting; Thomas Clancy suggests that, though not obviously connected to Scottish territory, it may ‘be the earliest poem by a woman to have been preserved in Britain’.24

If ‘The Dream of the Rood’ and the surviving Columban works owe their origins to the relative peace of monastic communities, The Gododdin is a reminder that early Scotland was frequently convulsed by the sort of warfare that led Adomnán to develop his laws protecting women, non-combatants and children. Among the heroic warriors of the Dark Ages, the Picts, who defeated that Anglian force at Dunnichen, and were themselves defeated by the Scots of Dál Riata, have left such splendid artworks as Christian and pre-Christian stones carved with Z-rods, combs, mirrors, beasts, and other symbols, but no extant literature. Their words survive only in a later Gaelic list of kings and in place names concentrated around Fife, Perthshire, Angus and the north-east. Occasionally there survives a personal name: Bliesblituth; Canutulachama. These alluring samplings come from a lost language which succumbed late in the first millennium to the greater cultural power of Gaelic. For all their military and artistic feats, the Picts have been silenced more effectively than the men of Gododdin. The English historian Henry of Huntingdon, in the 1120s, regarded the disappearance of the Pictish tongue ‘which was one of those established by God created at the very beginning of languages’ as truly ‘amazing’.25

So it is that the annotations in the Book of Deer from a north-eastern Columban monastery in Buchan are in Gaelic, not in Pictish. This version of the Latin Gospels, ascribed largely to the ninth century, has an Old Irish tailpiece or colophon. Its notes, written in the margins and other blank spaces, provide the earliest known example of continuous written Gaelic in a manuscript in Scotland. Among the notes is a legendary account of the monastery’s foundation which culminates with a characteristic Irish and Scottish literary genre, the Dindshenchas or legend of how a place got its name. The founding of the monastery is attributed to Columba and one of his disciples who has a Pictish name, Drostán, though his father’s name is Gaelic, Coscrach.

Iar sen do-rat Collum Cille do Drostán in chadraig-sen, 7 ro-s benact, 7 fo-rácaib i[n] mbréther, ge bé tíisad ris, ná bad blienec buadacc. Tángator déara Drostán ar scarthain fri Collum Cille. Ro laboir Colum Cille, ‘Be[d] Déar [a] anim ó [s]hunn imacc.

Thereupon Columba gave Drostán that monastery, and blessed it, and left the curse that whoever should go against it should not be full of years or of success. Drostán’s tears [déra] came as he was parting from Columba. Columba said, ‘Let Deer be its name from this on.’26

There are some other indications of Pictish/Gaelic crossover, but these notes from north-eastern Scotland testify to the written pre-eminence of the literary dialect of Gaelic, with some vernacular influence. For more sustained literary works we must return to Iona where the poet Mugrón, Abbot from 965 until his death in 981, has left several Gaelic poems. Iona had suffered at the hands of Viking attackers, losing sixty-eight monks in a massacre by raiders in the year 806, and had been partly eclipsed by the prestige of the monastery at Kells. However, by Mugrón’s time some of the Norse visitors were more friendly, and regarded Iona as a sacred site; Olaf Cuaran travelled to Iona as a pilgrim in the year 980, and died there peacefully. One of Mugrón’s poems is in praise of Columba, recalling the saint as, among other things, an eager author. Another, incantatory twelve-stanza poem by Mugrón draws, like ‘The Dream of the Rood’, on the cult of the cross. Instead of emphasizing the cross’s suffering, Mugrón presents it as a potent emblem of protection. His ritualistic repetitions generate a verbal interlacing which binds the cross to the poem’s speaker:

Cros Chríst tar mo láma

óm gúaillib com basa.

Cros Chríst tar mo lesa.

Cros Chríst tar mo chasa.

Cros Chríst lem ar m’agaid.

Cros Chríst lem im degaid.

Cros Chríst fri cach ndoraid

eitir fán is telaig.

Christ’s cross across my arms

from my shoulders to my hands.

Christ’s cross across my thighs.

Christ’s cross across my legs.

Christ’s cross with me before.

Christ’s cross with me behind.

Christ’s cross against each trouble

both on hillock and in glen.27

Physical as well as spiritual protective clothing remained desirable on tenth-century Iona. Mugrón’s successor as Abbot was killed along with fifteen monks on Christmas Night 986 by marauding Danes from Dublin. Gone were the days when Adomnán’s Laws protected noncombatants. Spreading terror through Hebridean communities with treasure to steal, the Vikings had begun their raids about two centuries earlier. With them they brought the Norse language when they began to settle in Orkney (conquered in the ninth century), Shetland, some of the Hebrides, and, later, Caithness. The King of Scotland would take possession of the Hebrides in 1266, but it would be 1468 before the northern isles came under the power of the Scottish throne. The celebrated prose Orkneyinga Saga records in Old Norse much of the heroic military and domestic history of Norse Orkney and Caithness. Composed in thirteenth-century Iceland, it was not translated into English until 1873, but has had a considerable impact on modern writing about Orkney, especially that of George Mackay Brown. The Orkneyinga Saga is full of factional fighting and power-play, typified in the reported words of the tenth-century Olaf Tryggvason, King of Norway, to the Earl of Orkney:

‘I want you and all your subjects to be baptized,’ he said when they met. ‘If you refuse, I’ll have you killed on the spot, and I swear that I’ll ravage every island with fire and steel.’

The Earl could see what kind of situation he was in and surrendered himself into Olaf’s hands… After that, all Orkney embraced the faith.28

Sometimes it can sound comically abrupt, but the sparely written Orkneyinga Saga is complex enough to epitomize its intricately ordered, remarkably cosmopolitan Orcadian world. Written in prose with many interpolated verses, it has at its heart an account of the martyrdom and miracles of Orkney’s St Magnus as well as the pilgrimage to the Holy Land made by Magnus’s nephew, the Orcadian warrior-poet Earl Rognvald Kali, and his men. Poems referring to Orkney and Caithness heroes and history recur in the Orkneyinga Saga and in the late thirteenth-century Njal’s Saga. Among them are verses attributed to the Icelander Arnor Thordarson, the ‘Jarlaskald’ (Earl’s Poet) who served as court bard to Orcadian rulers, elegizing Thorfin of Orkney, who died around 1065. He is recalled as a hard fighter.

These accounts are preserved in Icelandic sagas – we possess a relatively small number of Norse poems from Scotland itself. The earliest are small fragments by Orm Barreyjarskald, whose nickname ‘Poet of Barra’ indicates that he was probably one of the Norse settlers in the Hebrides. In these fragments we hear the sea crash on the shingle, and detect a note of Christian praise poetry as the speaker appears to look forward to being welcomed by God, ‘ruler… of the cart-way’.29 These atmospheric shards belong to the tradition of Norse skaldic verse which originated in Scandinavian Viking rulers’ courts. Professional poets, skalds, were employed to praise their brave, generous lord, and to entertain his followers, sometimes by hymning the noble dead. A Norse lay in memory of Eric Bloodaxe, King of the Norse settlement of York, is thought to have been composed in tenth-century Orkney, where Eric’s widow had fled after his death in battle in 954. As skaldic forms developed, they came to deal with a variety of subjects, including love, the heroic past, and Christian pilgrimage. Most of the Norse poems surviving from Scotland are written in variants of the court metre, the dróttkvætt, whose stanza contains eight six-syllable lines laced together by means of a complex pattern of alliteration and rhyming syllables. Half-rhyme as well as full rhyme is used within the lines and the language of these Norse poems is highly elaborate. Not only are the poetic metaphorical constructions known as ‘kennings’ employed, but there are also many heiti – periphrases for mundane objects.

All this speaks of a highly sophisticated literature whose flowering in the territories that belong to modern Scotland comes with the work of Earl Rognvald Kali. A Norwegian nobleman with ‘light chestnut hair’ who claimed the northern isles in the 1130s from his cousin, he commanded the building of the impressive cathedral in Kirkwall, in memory of his uncle, St Magnus. Murdered in Caithness in 1158, Rognvald is remembered as St Ronald of Orkney, and his relics are still in St Magnus Cathedral. A poet and patron of poets, he is celebrated at length in the Orkneyinga Saga – ‘a many-sided man and a fine poet’.30 To Rognvald is attributed the Háttalykill, or ‘Key of Metres’, a verse text that exemplifies all the metres of Norse poetry. A lot of his surviving poems in the Orkneyinga Saga deal with the pilgrimage to the Holy Land which he made between 1151 and 1153. On his way there, for a time he stayed at Narbonne in the south of France and addressed poems to its female ruler, Ermengard. These works, admiring the lady’s cascading hair and white arms, reveal the first datable Troubadour influence on Norse writing. A sense of Rognvald’s aristocratic sophistication is clearly communicated by the dróttkvætt piece (reprinted in the original Norse and in translation in The Penguin Book of Scottish Verse) in which he outlines the attributes of a gentleman:

Chess I’m eager to play,

nine skills I know,

I scarcely forget runes,

book and handicrafts are my custom,

I can glide on skis,

I shoot and row as well as serve,

I know how to consider

both harp-playing and poetry.31

Rognvald’s poems communicate not just a superb technical and emotional assurance, but also lyricism and humour. Mocking Irish monks on a windy island whom he sees as womanly in their monks’ clothing, he deploys elaborate language to draw attention to their tonsured heads, then concludes with a well-prepared, yet still striking punchline which complains how these ‘girls… out west’ are all ‘bald’.32 Acute and versatile, leader of a circle of poets, the Norwegian Rognvald, this ruler of Orkney who learned from the Troubadours in his devotion to the Lady Ermengard, stands as one of the most remarkable early named poets of Scotland.

About Ermengard Scottish sources have far less to say than they do about Queen Margaret (d. 1093), the first woman in Scotland of whom a detailed biographical account survives. Written in Latin around 1105 by Turgot, Margaret’s confessor, this Vita (Life) dates from about half a century before Rognvald’s poems. Although Turgot became Bishop of St Andrews at the end of his life, and may have spent time in Norway and in Scotland as a younger man, he probably belonged to a Norse-descended family and lived much of his life in Durham, where he helped found the cathedral in 1093. Writing the life of Margaret at the request of her daughter Matilda who had become Queen of England, Turgot produces an elegant biography. Margaret was the wife of a Scottish King, Mael Coluim III (Malcolm Canmore), who was often in armed conflict with the rulers of England in a series of bloody incursions and counter-raids. Turgot’s Life, though, largely avoids this material. It makes no mention of Margaret’s Hungarian birth, or of Malcolm’s first wife, Ingibjorg, widow of Thorfinn, Earl of Orkney. Instead, the biography’s political and ecclesiastical underpinnings suggest ways in which Margaret, who had grown up as a princess in England, offers an example of an Englishwoman devoted to the service of God, Scotland and Scotland’s king, yet at the same time promoting English Church government and customs.

The Margaret of this Life is generous to victims of poverty and war, such as English slaves in Scotland, whose ransoms she pays. Turgot’s writing is politically motivated, but in a complex way – one designed to appeal to an English queen while celebrating a Scottish saint of the Church who is a learned woman, thoroughly well read in scripture and constantly meditating on God’s word. Ascetic, Margaret eats disturbingly little, but radiates domestic and spiritual power. With impressive results, she instils God-fearing and rod-fearing behaviour into her offspring, instructing their governor ‘to curb the children, to scold them, and to whip them when they were naughty, as frolicsome children will often be’. Yet, demonstrating personal kindness to rich and poor alike, Margaret exemplifies the shining, pearl-like virtue which, Turgot points out with a characteristic medieval fondness for the meaning of names, goes with the word ‘Margaret’ (margarita means ‘pearl’ in Latin). Her veneration of the cross leads eventually to the founding of Edinburgh’s Holyrood Abbey; she was directly responsible for other foundations, such as that of Holy Trinity in Dunfermline. Like Columba and most medieval saints, she meditates constantly on ‘the terrible day of judgment’. She is also portrayed as encouraging her husband’s wisdom and piety. In prayer she teaches the warlord how to cry. As a nineteenth-century Scottish translation of the medieval Latin indicates, Turgot presents the bookish Queen Margaret and her husband as devoted to each other, but quite different in their attitudes to culture:

There was in him a sort of dread of offending one whose life was so venerable; for he could not but perceive from her conduct that Christ dwelt within her; nay, more, he readily obeyed her wishes and prudent counsels in all things. Whatever she refused, he refused also; whatever pleased her, he also loved for the love of her. Hence it was that, although he could not read, he would turn over and examine books which she used either for her devotions or her study; and whenever he heard her express liking for a particular book, he also would look at it with special interest, kissing it, and often taking it into his hands. Sometimes he sent for a worker in precious metals, whom he commanded to ornament that volume with gold and gems, and when the work was finished, the king himself used to carry the book to the queen as a loving proof of his devotion.33

Margaret is presented as a source of wise advice, learning and kindness; her illiterate husband here seems charmingly naive. Yet the linguistically adroit Malcolm, who had spent his formative years in English exile, and who ruled an unruly kingdom for longer than any other eleventh-century Scottish monarch, was clearly more than a charming naif. His native language was Gaelic, a foreign tongue to Margaret and to Turgot, neither of whom seems to have learned it. Where the culture of Latin scripture was very much a textual one, poetry in Gaelic was still in the main orally transmitted, and would continue to be so for most of the following millennium. Turgot’s beautiful Life is very much a politically and aesthetically shaped work; its account of Margaret on her deathbed receiving news of the killing of her husband is psychologically dramatic. Its earlier vignette, typical of saints’ lives, records the miraculous preservation of Margaret’s Gospel Book when a priest let it fall into a river. A Scottish Latin poem, added to the volume in Margaret’s lifetime, concludes,

Saluati semper sint Rex Reginaque sancta,

Quorum codex erat nuper saluatus ab undis.

Eternal salvation to the King and holy Queen

Whose book was only now saved from the waves.34

Generously, the poet’s use of the plural ‘Quorum’ (whose) indicates that the book in question belongs to both Margaret and Malcolm. Remarkably, this Latin lectionary still survives, suitably dried out, in the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

That Scotland, or parts of it, around the time of Margaret’s death could be perceived as a place of culture is implied by a Gaelic poem, the Duan Albanach, dated to around 1093. Probably made by an Irish poet, this work begins by addressing the Scots as ‘you learned ones of Alba’.35 From the late ninth century ‘Alba’ was used as the Gaelic name for Scotland north of the River Forth, an area to which the word ‘Scotia’ was applied in the eleventh century, before in the 1200s ‘Scotia’ came to designate all of mainland Scotland. Surviving poetry attests to the way Columba’s memory continued to be venerated in the Scotland of Margaret’s son, King Alexander I, who furthered the work of English Augustinian canons at Scone and elsewhere. During the reign of Alexander’s brother Edgar, who ruled before him and whose ostentatious royal seal bore the words ‘Imago Edgari Scottorum Basilei’ (‘Emblem of Edgar, High King of Scots’), sealed Latin writs had been introduced into the country, further developing the written authority of the Scottish monarch.36 Yet the most beautiful writing of the twelfth century to deal with a Scottish theme is not a Latin, but a Gaelic work. ‘Arann’, whose author may have come from Scotland or Ireland, rejoices in the natural richness of the large island of Arran in the mouth of the Firth of Clyde. The seven rhyming quatrains of this packed and delightful lyric begin,

Arann na n-oigheadh n-iomdha,

tadhall fairrge re a formna;

oiléan i mbearntar buidhne,

druimne i ndeargthar gaoi gorma.

Ard ós a muir a mullach,

caomh a luibh, tearc a tonnach;

oiléan gorm groigheach gleannach,

corr bheannach dhoireach dhrongach.

Oighe baotha ar a beannaibh,

mónainn mbaotha ina mongaibh,

uisge uar ina haibhnith,

meas ar a dairghibh donnaibh.

Arran of the many deer,

ocean touching its shoulders;

island where troops are ruined,

ridge where blue spears are blooded.

High above the sea its summit,

dear its green growth, rare its bogland;

blue island of glens, of horses,

of peaked mountains, oaks and armies.

Frisky deer on its mountains,

moist bogberries in its thickets,

cold water in its rivers,

acorns on its brown oak trees.37

Celebrating a heroic ideal, this poem shows a delight in the mountainous natural environment and its inhabitants that will recur in much later Gaelic poetry and which, however refracted, will condition Romantic poetry in English and other languages. Yet it would be wrong to read these verses only in terms of what they appear to anticipate. They are part of an interlacing of traditions and literatures in early Scotland where, however terrible the movements of warfare across the landscape (and this poem with its ‘troops… ruined’ is alert to these), there are also moments when a sensuous beauty – whether of Arran’s mountains or of scents on Iona – can be relished both for itself and as part of a larger, divinely ordered harmony. ‘Fine at all times is Arran.’38

In this period when even kings might be illiterate, when much composition was for oral recitation, and when reading and writing were arts largely belonging to monks or other clerics, writers tended to be in holy orders. There were as yet no universities in Scotland, though learned men such as the twelfth-century philosopher Adam Scot, Abbot of Dryburgh Abbey, may have given classes.39 Not until 1411 would Scotland’s first university be established at the ecclesiastical capital, St Andrews. Scots wanting a university education in the twelfth century had to travel to Europe to the newly founded Schools of Paris or Bologna, the first of their kind. A number of distinguished twelfth-century Scottish intellectuals gravitated towards these growing continental centres of thought. One such man was Richard Scot (c. 1123–73), remembered in France as Richard de St Victor because he became Prior of the Abbey of St Victor in Paris. As a philosopher he followed St Anselm of Canterbury in viewing love as a crucial feature of the universe. He influenced the Franciscan order (established in the early thirteenth century), and not least its leading philosopher, his countryman Duns Scotus.

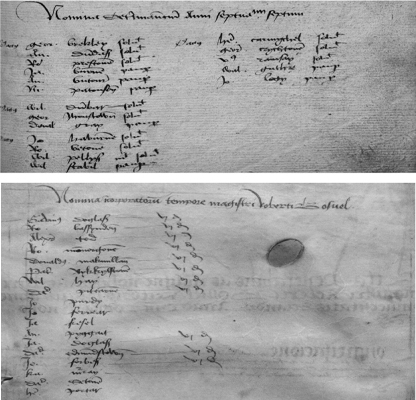

Occasionally, surviving manuscripts offer us detailed glimpses of the work of these Scottish writers and thinkers in continental Europe:

Perfectus est liber Auen Alpetraus, laudetur Ihesus Christus qui uiuit in eternum per tempora, translatus a magistro Michaele Scoto Tholeti in 18° die ueneris augusti hora tertia cum Abuteo leuite anno incarnationis Ihesu Christi 1217.

Praise be to Jesus Christ who lives for ever in eternity, the book of Alpetraus [Al-Bitrûjî] is completed, translated by Master Michael Scot with the Levite Abuteus at Toledo at the third hour on Friday the 18th day of August in the year AD 1217.40

No early written work produced by a Scot can be placed or dated more precisely than this translation of De Motibus Celorum (On the Movements of the Heavens) by the twelfth-century Spanish Aristotelian Al-Bitruûjî, last of the major Arab astronomers whose work reached the West from Islamic culture in Scholastic times. Perhaps because of the help of Abuteus, Scot’s syntax closely tracks that of the Arabic as it expounds matters of spherical trigonometry. Michael Scot (c. 1160–1235) followed this work with translations of the twelfth-century Arab philosopher Averroes’s commentaries on Aristotle as well as texts about animals by Aristotle himself. Such endeavours gave Scot access to an advanced synthesis of Greek and Arabic philosophy, preparing the way for his own encyclopedic writings in Latin. These established him as the leading early thirteenth-century Western European intellectual.

Scot worked in Toledo, Bologna, and at the court of Frederick II at Palermo. Translating into Latin from the Arabic of Islamic authors as well as from Hebrew, Scot, in the words of Maria Rosa Menocal, ‘was himself a sort of translation’ and became ‘the most famous of medieval translators’.41 Praised by the Pope for his remarkable learning, he was elected Archbishop of Cashel in Ireland, but did not reside there, and resigned because he knew no Irish. His great, unfinished work in three parts – the Liber introductorius (Introductory Book), its supplementary Liber particularis and the Liber physiognomae – is dedicated to Frederick II. The first two parts especially are full of the digressions and encyclopedic wanderings that characterize Scot’s writings as he discusses such matters as the twenty-eight mansions of the moon, or the centre of the earth as an infernal prison for damned spirits.

Scot’s work is full of curiosities. He informs his readers that in many parts of the world eggs are not put under hens but carried by women next to their breasts until the chickens hatch. Yet elsewhere he demonstrates an impressive knowledge of anatomical dissection and close observation. A scientist preoccupied with astronomy and astrology at a time when the two were deeply intertwined, Scot wrote stylishly. Fascinated by names and etymologies, he uses a wide Latin vocabulary spiced with new coinages. Though at times rhetorically elaborate, he often deploys clear, simple illustrative examples. So the universe is whole and round like an apple, filled with seeds for future development. God made and makes the world’s marvels, delighting in them like a juggler. A passage from the Latin Liber introductorius describing the character of a man born under the influence of the planet Mercury has been regarded in modern scholarship as a possible self-portrait:

A mercurial person naturally delights in an easy, honourable and peaceful occupation, albeit unprofitable at certain times of the year. He is serious and a great reader, notes important questions, and wants to know all the answers. He is interested in miniatures, painting, sculpture, school-teaching and wants to be able to instruct scholars or disciples in white magic, to engage in business, and to perform tricks and subtleties which give pleasure to others.42

Though praised by the Pope, and generally orthodox, Scot’s amazingly wide-ranging learning brought him a posthumous reputation as a magician. His writings, while condemning necromancy, do display a knowledge of books of magic. There is no evidence that he practised any. In the following century, however, rumours earned him the singular distinction of becoming the only Scot whom Dante placed in Hell:

Michele Scotto fu, che veramente

delle magiche frode seppe il gioco.

The late Michael Scot, who truly

Knew every trick of the magician’s art.43

Scot’s works were influential in medieval Europe. The Liber physiognomae was printed in no fewer than twenty editions before 1500, and other works (some concerning magic) were falsely attributed to him. Supposedly a son of Kirkcaldy who lies buried in Melrose Abbey, he is remembered as a medieval man of supernatural knowledge, and still enjoys a remarkable range of afterlives, featuring in novels, poems, and even as a hero in a Canadian children’s television series. In the land of his birth he was remembered not least by that later Scott, Sir Walter, who rejoiced in his own soubriquet as ‘Wizard of the North’.

The posthumously accredited wizardry of Michael Scot was matched in Scotland by the miraculous prophetic powers attributed to the thirteenth-century poet remembered as Thomas the Rhymer. Sometimes this poet is also styled ‘Thomas of Erceldoune’, taking his name from a village in Berwickshire. A surviving late twelfth-century legal deed associated with Melrose Abbey is recorded as being witnessed by ‘Thomas Rymor de Ercildune’, but no literary works by this shadowy figure survive in their original form. What we have is a three-part poem of about 700 lines in a number of fifteenth-century manuscripts, all presenting the story of how Thomas of Erceldoune meets a mysterious fairy woman. The poem opens in the first person with the speaker ‘In a mery mornynge of Maye,/ By huntle bankkes my self allone’, listening to birds singing. Other parts of the poem present this figure in the third person, making it clear that he is Thomas of Erceldoune, and that a ‘lady gaye’ who says she is ‘of ane other countree’ takes him away for a year underground ‘at Eldone hill’ where he sees marvels and hears many prophecies before his return.44 The story of Thomas involves an older narrative attached to a very specific Scottish location at Huntly Bank, near Melrose, and containing popular Scottish prophetic materials. In written form it has survived only in later English redactions, though there is plenty of evidence that the story circulated in Scotland through oral ballads and, a good deal later, in printed versions. Throughout the ensuing centuries Thomas and his prophecies attracted many Scottish authors, not least Walter Scott who wrongly attributed to him the northern English metrical romance Sir Tristrem, which begins, ‘I was at ertheldoun/ With tomas spak y thare.’45 Posthumously Thomas, like Michael Scot, would acquire the powerful allure of a literary magus.

Equally potent, and with a more tangible physical presence in twelfth-century Scotland, was the impact of the Norsemen. A contemporary Latin poem by a Glaswegian named William attributes to St Kentigern, patron saint of Glasgow where he is also known as St Mungo, the strength to defeat an ‘immense army’ of rampaging ‘Norsemen and Argyllsmen’ at the Battle of Renfrew in 1164. In this fight Somerled (Somairlid mac Gille-Brighde), Lord of Argyll and the Isles, was killed – much to the poet’s relief. Somerled clearly terrifies the Glaswegians of William’s poem, though they do fight back. A cleric chops off the Norse lord’s head and places it in the outstretched hands of the Bishop of Glasgow. Earlier in his poem William builds up a sense of vigorous suspense as Somerled’s armed fleet approaches up the Clyde.

Debachantur et vastantur orti, campi, aratra;

Dominatur et minatur mites manus barbara.

Glasguensis ictus ensis laesus fugit populus.

Gardens, fields and plough-lands were laid waste and destroyed;

the gentle, menaced by barbarous hands, were overwhelmed.

Wounded, Glasgow’s people fled the blows of swords…46

The Norse wielders of violent weapons celebrated their exploits in poems such as the Krakumal, which probably dates from the mid-twelfth century and may have been composed on Orkney or in the Hebrides. Ostensibly the final utterance of the ninth-century Ragnar Lothbrok (Leather Breeches), who has been flung into a snake-pit by King Ælla of Northumbria, this extended poem works variations on the dróttkvætt stanza. Its speaker dies with defiant laughter on his lips, and the poem articulates with relentless, controlled aggression the raids of a Viking crew. Each stanza starts with a war-whoop of sword-swinging self-praise, then goes on to chronicle savage attacks on locations in continental Europe, the Hebrides, and ‘far and wide in Scotland’s firths’.47

In this twelfth-and thirteenth-century period the Norse presence in the Western Isles, Ireland and the north and west of the Scottish mainland is strong. The Gaelic Raghnall, King of Man and the Isles (1187–1229), has a name which comes from the Norse ‘Rognvald’, and is praised in a substantial Gaelic poem, many of whose nautical and military terms are derived from Norse. Such works both draw on and add to a literature of heroic praise, but a note closer to parody creeps into the Norse ‘Song of the Jomsvikings’ attributed to Bjarni Kolbeinsson, Bishop of Orkney from 1188 until 1223. Though some of this work is lost, its surviving forty-five stanzas in the munnvorp metre (a kind of dróttkvætt) show evidence of an imagination that likes to play with and even subvert skaldic conventions. Where at the start most poets might be expected to demand silence for their poem, this poet seems determined to press on with his performance whether or not ‘the noble/ knights will listen to me’, and later on he addresses ‘those not listening’.48 A sense of a parodic or ironic sensibility continues as the poem mixes the expected materials of Norse heroic exploits with repeated asides about the poet’s longing for another man’s wife. Aspects of this are reminiscent of Rognvald Kali’s Troubadour-influenced work. Though Kolbeinsson’s poem can be heroically harsh, it is shot through with flickers of po-faced humour. Like Rognvald Kali’s verse, its tonal sophistication can appeal to a modern audience.

The attraction of mixed comic and heroic tonalities is also strong in a remarkable early thirteenth-century work linked to southern Scotland. This is the Norman French Roman de Fergus which survives only in continental manuscripts, but whose detailed knowledge of the topography and customs of Scotland suggests an author who had spent time in that country. In 1991, the scholar of medieval French D. D. R. Owen argued that its author, known only as ‘Guillaume le Clerc’, was probably William Malveisin. This Frenchman appears to have come to Scotland in the 1180s, becoming by 1190 Archdeacon of Lothian before going on to serve as Bishop of Glasgow from 1200 until 1202 when he was made Bishop of St Andrews, a position he occupied until his death in 1238.49 At just under 7000 lines, the Old French romance of Fergus is both a tale of derring-do in octosyllabic rhyming couplets and a sophisticated spoof of the sort of Arthurian chivalric metrical tale made classic by Chrétien de Troyes, greatest of the French medieval poets, who died in the 1180s.

Fergus is not quite the model Arthurian hero. For a start, he comes from Galloway, an area decried by outsiders for its backwardness, and troublesome to both Scottish and English kings. Serlo, a thoroughly biased mid-twelfth-century English Latin poet, had written of the Gallovidians (whom he called ‘Picts’), ‘Et quas prius extulerunt caudis nates comprimunt’ (They use their once-raised tails to shield their arse) and he mocked their supposed preference for raw meat.50 Fergus, whose ancient name is also that of a twelfth-century King of Galloway, is presented by Guillaume as the son of ‘Soumillet’ (Somerled), which makes him doubly barbarous. Comically, he first appears as a knight wearing a rusty old suit of armour and carrying a smoke-blackened lance. Dressed like this, he travels to Arthur’s court where he is mocked by Sir Kay. Replying with an appropriate oath, ‘Par Sai[n]t Mangon qui’st a Glacou’ (By St Mungo of Glasgow), Fergus sets off to prove himself a worthy knight, and to win the hand of the beautiful Galiene at Liddel Castle – Castleton in modern Roxburghshire.51 Galiene first of all throws herself at Fergus, only to be rebuffed, and the poem continually sends up not just the conventions of romantic love but also well-known episodes and motifs from Old French Arthurian romances. A mixture of heroism and ineptitude makes Fergus all the more appealing. Nowhere is this more pronounced than in the way he accomplishes the most demanding of his tasks, vanquishing the north-eastern supernatural forces ranged against him near modern Stonehaven at Dunottar. There, below the spectacular ruined seaside castle, you can still see Fergus’s dragon’s cave. Doing battle with his formidable Dunottar dragon, our hero falls over:

A Fergus desplot molt ceste uevre

Et saciés que molt li anuie.

Uns autres fust mis a la fuie;

Mais mius velt morir a honnor

Que vivre et faire deshonnor

Et que li tornast a reproce.

Li sans li saut parmi la boche

Et par orelles et par le nés

Que tos en est ensanglentés.

Et quant il aperçut le sanc

Qui li arousse l’auberc blanc

Lors a tel dol, a poi ne font.

La targe lieve contremont,

Si fiert, iriés comme lion,

Del branc le serpent a bandon

Sor le hance qu’ot hirechie,

Que en travers li a trenchie

La teste et le col a moitié.

Mick Imlah’s modern verse translation of this passage is a free one, yet catches something of the tone of the original:

As if in a Highland melodrama,

Fergus cursed through fractured armour.

His only comfort where he lay,

That chevalier of Galloway,

Was joining, since he hadn’t fled,

The ranks of the heroic dead.

For so much blood had spouted out

Of his face from the first round of the bout

That when his eyes fell on the hue

Of the tunic he had put on blue,

He almost fainted in distress

At the ruined state of his warrior dress.

Instead, provoked by the red rag,

He sprang up like a cornered stag

And lashed out with his wounded pride

At the tough scales of the serpent’s hide: –

Then slicing up at the shocked head,

Severed the neck and dropped her dead.52

After many further trials Fergus wins his lady and is recognized as a true hero by all the Arthurian court. A product far less of ‘holy reading’ than of a mischievous literary imagination steeped in a fashionable Arthurian canon, Fergus takes us through a Scotland that is enjoyably suspended between the endless forests of knightly questing and the precisely realized topography of northern Britain. As well as meeting giants and dragons, our praiseworthy hero endures a stormy crossing from Queensferry as he travels north along the recognizable pilgrims’ route to Dunfermline. Relying on the supposed barbarousness of the Gallovidian Scot and appealing to the sophisticated taste of an audience used to secular romances, Fergus is an outstandingly polished performance from a period when heroic deeds and literary conventions might be viewed through the eye of parody, yet still relished for their genuine excitement and gusto. This is praise with a wink in it.

At a time when different political and linguistic communities in Scotland might view one another with terror, interest and occasional amusement, the great, measured, beautiful music of Gaelic poets active in the west and in Ireland sounds a more traditional note of praise uncorroded by irony. Gille-Brighde Albanach, whose bardic career was at its height in the first three decades of the thirteenth century, was a poet from the ‘lovely yellow woods’ of Scotland who composed according to the metrically strict rules of classic bardic poetry and who wrote in praise of Irish monarchs such as Cathal Crobhdherg (‘Redhand’), King of Connacht. His praise-poem links the king’s strength and justice to the good health of the terrain he rules over, with its green, nut-rich woods and ‘luscious turf’.53 This poem of thirty-six quatrains summons up epithets and terms of praise familiar from six centuries earlier. Where Beccán of Rhum in the 600s had called Columba ‘Caindel Connacht’ (Connacht’s candle), so these later verses hymning an early thirteenth-century King of Connacht style him ‘choinnle Tuama’ (Tuam’s candle).54 The elaborate variations of praise are vivid as they bond the king to the landscape and pursuits of his kingdom. So his ‘sure hand’ is ‘Whiter than a shirt on washing day’, while in Connacht ‘struck with a mallet, each white hazel/ will pour down the fill of a vat’.55 Although Gille-Brighde tells us that he was Scottish, his heart seems to have been in Ireland. Another poem for the same king, written from Scotland, remembers with tears of longing Ireland’s ‘land of round, wooded hillocks,/ wet land of eggs and birdflocks’.56

As they had done for the best part of a millennium, Gaelic poets continued to move between Ireland and Scotland. If Gille-Brighde was a Scot working for Irish patrons, then his contemporary Muireadhach Albanach Ó Dálaigh was a poet from Ireland’s principal poetic family. He had been bard to the ruler of Tir Conaill, Domhnall Mór Ó Domhnaill, but had fled to Scotland after a quarrel. Spending about fifteen years in Scotland, this poet acquired the epithet ‘Albanach’ (Scotsman) and, settling in his new homeland, is said to be the ancestor of the most famous Scottish family of Gaelic bards, the MacMhuirichs. Two surviving early thirteenth-century poems by him praise the rulers of Lennox whose territorial headquarters was at Balloch in Dumbartonshire. Their descent from a noble Irish family is made much of. In comparison with the substantial amount of work surviving from Ireland, only a small amount of Scottish bardic poetry now exists, and Wilson McLeod points out that Muireadhach Albanach’s poem for Alun, first Earl of Lennox (who died around the year 1200), is ‘the earliest extant bardic poem composed for a Scottish chief’.57 Like Gille-Brighde, Muireadhach Albanach participated as a pilgrim in the Fifth Crusade. Beginning in 1217, this involved the temporary capture of the Egyptian fort of Damietta the following year. Muireadhach made a Gaelic poem ‘Upon Tonsuring’, about having his head shaved. It probably dates from his time as a crusader. His shorn curls are a sacrifice to God: ‘This fair hair, Maker, is yours.’58 Damietta was lost again in 1221 and its siege resulted in severe casualties among the crusading army. A homesick poem made by Muireadhach at Monte Gargano records some of the losses, and exclaims with longing that it would be ‘Like Heaven’s pay, tonight, to touch/ Scotland of the high places’.59

Compiled much later, in sixteenth-century Perthshire, the Book of the Dean of Lismore is now one of the treasures of the National Library of Scotland. It includes selections from Scots poets like Henryson and Dunbar but is famous as the most precious of early Scottish Gaelic manuscripts. Brought to the attention of eighteenth-century antiquaries by James ‘Ossian’ Macpherson, it contains unique transcripts of many earlier poems by Scottish and Irish poets. Among these is what modern readers may consider the most moving work by Muireadhach Albanach, his ‘Elegy on Mael Mhedha, his Wife’. Its intricately rhyming quatrains communicate with remarkably sustained lyricism a sense of love, hurt and sundering:

Do bhí duine go ndreich moill

ina luighe ar leith mo phill;

gan bharamhail acht bláth cuill

don sgáth duinn bhanamhail bhinn.

Maol Mheadha na malach ndonn

mo dhabhach mheadha a-raon rom;

mo chridhe an sgáth do sgar riom,

bláth mhionn arna car do chrom.

Táinig an chlí as ar gcuing,

agus dí ráinig mar roinn:

corp idir dá aisil inn

ar dtocht don fhinn mhaisigh mhoill.

There was a soft-gazed woman

lay on one side of my bed;

none like her but the hazel’s flower,

that dark shadow, womanly, sweet.

Mael Mhedha of the dark brows,

my cask of mead at my side;

my heart, the shadow split from me,

flowers’ crown, planted, now bowed down.

My body’s gone from my grip

and has fallen to her share;

my body’s splintered in two,

since she’s gone, soft, fine and fair.60

A poet of emotional power and utterly convincing thematic range, Muireadhach Albanach also wrote a beautiful and erotically charged poem addressed to the Virgin Mary, longing for her ‘young round sharp blue eye’ and ‘soft tresses’:

A ÓghMhuire, a abhra dubh,

a mhórmhuine, a ghardha geal,

tug, a cheann báidhe na mban,

damh tar ceann mo náire neamh.

O Virgin Mary, O dark brow,

O great nurse, O garden gay,

of all women the most beloved,

give me heaven despite my shame.61

In terms of its extensiveness, the high point of Gaelic culture in Scotland was around the late ninth century when the court appears to have been an important centre of literary patronage. Although much later, in 1249, King Alexander III had his genealogy read to him in Gaelic by a King’s Poet as part of his coronation at Scone, from the late eleventh century the royal court became de-Gaelicized so that the professional literary men known as filidh who had been attached to kings and major local rulers turned their attention elsewhere. A lower order of poets, the baird or bards (among whom the Ó Dálaighs were prominent), went on developing and making poems, particularly in western and Highland areas. By the twelfth century the Scottish court and the agriculturally rich lands of Lowland Scotland were only vestigially Gaelic. That language was increasingly identified with the less agriculturally productive Highlands and with western areas, especially the Hebrides. As the filidh declined and the baird developed, praise-poetry in vernacular Scottish Gaelic began to break free of older classical Irish models. Still, making genealogically alert poems and serving just a few families, Scottish bardic poets may have continued to look and listen to Ireland for at least part of their training, even when, like Gille-Brighde Albanach, they were not Irish by birth. Scottish bardic poets liked to emphasize Irish connections, whereas Irish poets paid relatively little attention to Scotland, and most of the medieval prose that survives in Gaelic is clearly Irish rather than Scottish in origin. The major prose works written by Scots in the Middle Ages, from the records of the early Scottish Parliament to elaborate philosophical treatises, are in Latin, not in Gaelic.

Gille-Brighde Albanach’s richly imaged Gaelic praise-poetry is very far indeed from the academic Latin prose of John Duns Scotus, greatest of Scotland’s early philosophers. Yet Duns Scotus’s work, like that of Muireadhach Albanach Ó Dálaigh in his hymn of praise to Mary, is grounded on the assumption that the Christian faith is what makes sense of the cosmos and our being in it. Defending his belief in Mary’s immaculate conception, Duns Scotus too argued that ‘what is most excellent should be attributed to Mary’.62 Born around 1266, apparently to a family linked to Duns in Berwickshire, the philosopher is thought to have been educated in Haddington, then ordained a priest at Northampton in 1291. A Franciscan, Duns Scotus was teaching at Oxford in 1300. Soon afterwards he studied and taught in Paris before moving to Cologne where he was lecturing in 1308, the year of his death. The elaborate catafalque containing his remains, now in the Minoritenkirche, Cologne, bears the inscription ‘Scotia me genuit, Anglia me suscepit, Gallia me docuit, Colonia me tenet’ (Scotland bore me, England reared me, France taught me, Cologne holds my remains). Michael Scot enjoyed a similarly peripatetic career, but where the earlier Scottish thinker’s prose is crammed with odd facts, digressions and entertaining images, the writing of Duns Scotus is unsparingly abstract, brilliantly analytical. Aspects of it have appealed to literary imaginations (notably that of Gerard Manley Hopkins), but Scotus is read today mostly by theologians, philosophers and the occasional historian of science.