Figure 1.12

AT SEVERAL POINTS in the book I have made comments about the way creativity is sometimes regarded. At various points later in the book I shall very likely make further comments. I feel, however, that there is some value in bringing together in one place these various points. This may lead to a degree of repetition, but that in itself can be useful. Quite obviously the views I put forward here are personal opinions based on many years’ experience in the field of creative thinking and the teaching of creative thinking skills.

This misperception is actually very convenient because it relieves everybody of the need to do anything about fostering creativity. If it is only available as a natural talent then there is no point in seeking to do anything about creativity.

The argument is usually set by pointing to rather extreme cases of creativity such as Mozart, Einstein, or Michelangelo. This is not unlike saying there is no point in teaching mathematics because mathematical geniuses like Poincaré cannot be produced to order. We do not give up teaching people to play the piano or violin because we cannot guarantee a Liszt or Paderewski from every pupil. Can you produce a Björn Borg or Martina Navratilova from every tennis pupil?

There are very useful levels of mathematical ability, piano playing, violin playing, and tennis playing, even when these fall short of genius.

Imagine a row of people lined up to run a race. The starting signal is given and the race is run. Someone comes first and someone comes last. Performance has depended on natural running ability. Now suppose someone invents the “roller skate” and gives all the runners some training on the roller skates. The race is run again. Everyone goes much faster than before. Someone will still come first and someone will still come last.

If we do nothing at all about creativity then obviously creative ability can only depend on “natural” talent. But if we provide training, structures, and systematic techniques, then we can raise the general level of creative ability. Some people will still be much better than others but everyone can acquire some creative skill. There is no contradiction at all between “talent” and “training”. Any athletics or opera coach can make that point.

That some people are naturally creative does not mean that such people would not be even more creative with some training and techniques. Nor does it mean that other people can never become creative.

When I first started writing about creativity I half expected truly creative people to say that they did not need such matters. Quite the contrary happened. Many well-known creative people got in touch with me to say how useful they found some of the processes.

At this point in time there is also a wealth of experience to show how people have used deliberate lateral thinking techniques to develop powerful ideas. There is also a lot of experience from others to show that training in creative thinking can make a significant difference.

On an experimental basis, it is quite easy to show how even as simple a technique as the random word can immediately lead to more ideas; ideas that are different from those that have been offered before.

In my view, learning creative thinking is no different from learning mathematics or any sport. We do not sit back and say that natural talent is sufficient and nothing can be done. We know that we can train people to a useful level of competence. We know that natural talent, where it exists, will be enhanced by the training and processes.

In my view, and at this point in time, I think the view that creativity cannot be learned is no longer tenable.

It may not be possible to train genius – but there is an awful lot of useful creativity that takes place without genius.

At school the more intelligent youngsters seem to be conformists. They quickly learn the “game” that is required: how to please the teacher. How to pass exams with minimal effort. How to copy when necessary. In this way they ensure a peaceful life and the ability to get on with what really interests them. Then there are the rebels. The rebels, for reasons of temperament or the need to be noticed, do not want to play the going game.

It is only natural to assume that in later life creativity is going to have to come from the rebels. The conformists are busily learning the appropriate games, playing them, and adjusting to them. So it is up to the rebels to challenge existing concepts and to set out to do things differently. The rebels have the courage, the energy, and the different points of view.

This is our traditional view of creativity. But it could be changing.

Once we begin to understand the nature of creativity (or at least, lateral thinking) then we can start laying out the “game” and the steps in the game. Once society decides that this game is worth playing and should be rewarded then we might well get the “conformists” deciding that they want to play this new “game”. So the conformists learn the game of creativity. Because they are adept at learning games and playing the games the conformists might soon become more creative than the rebels who do not want to learn or play any games.

So we might get the strange paradox that the conformists actually become more creative than the rebels. I think this is beginning to happen.

If it does happen I would expect to see much more constructive creativity. The rebel often achieves creativity by striking out against the prevailing ideas and going against current idioms. The momentum of the rebel is obtained by being “against” something. But the creativity of conformists (playing the creative game) does not need to be “against” anything – so it can be more constructive and can also build on existing ideas.

So creativity is certainly not restricted to rebels but creative skills can be acquired even by those who have always considered themselves conformists.

Japan has produced many highly creative people but on the whole the Japanese culture is oriented towards group behaviour rather than individual eccentricity. Traditional Japanese culture has not put a high value on individual creativity (in contrast to the West). In a smooth arch it is not necessary to see the individual contribution of each stone.

Things have changed. The Japanese have become good at this new game. They have learned to play the creativity game. So they have now decided to learn to play the game. In my experience in teaching creativity in Japan I would have to say that they are going to be very good at this “new” game. Just as they learned to play the “quality” game very well, so they will also learn the creativity game and play it well.

The West will be left somewhat behind if those responsible for education in the West still believe that creativity cannot be taught and that critical thinking is enough.

The simple geography of right brain/left brain has made it very appealing – to the point that there is almost a hemispheric racism:

“He’s too left-brained”

“We need a right-brained person for this …”

“We employed her to bring some right brain to bear on the matter …”

While the right/left notation has some value in indicating that not all thinking is linear and symbolic the matter has been exaggerated to the point that it is dangerous and limiting and doing great harm to the cause of creativity.

In a right-handed person the left brain is the “educated” part of the brain and picks up on language, symbols, and seeing things as we know they should be. The right brain is the uneducated “innocent” that has learned nothing. So in matters of drawing, music, and the like, the right brain can see things with an innocent eye. You might draw things as they really look, not as you think they ought to be.

The right brain might allow a more holistic view instead of building things up point by point.

All these things have a value, but when we come to the creativity involved in changing concepts and perceptions, we have no choice but to use the left brain as well because that is where concepts and perceptions are formed and lodged. It is possible to see which parts of the brain are working at any given moment by doing a PET (Positron Emission Tomography) scan. Little flashes of radiation captured on a film show the activity. It seems clear that when a person is doing creative thinking both left and right brains are active at the same time. This is much as one might expect.

So while there is some merit in the right/left brain notation and some value for innocence in certain activities (music, drawing) the basic concept is misleading when it comes to creative thinking. It is misleading because it suggests that creativity only takes place in the right brain. It is misleading because it suggests that in order to be creative all we need to do is to drop the left brain behaviour and use right brain behaviour.

Earlier I mentioned the confusion caused by the very broad usage of the word “creativity”. Normally we see “creativity” most manifestly in the work of artists so we assume that creativity and art are synonymous. As a result of this confusion we believe that to teach creativity we must teach people to behave like artists. We also assume that artists might be the best people to teach creativity.

In this book I am concerned with the creativity involved in changing concepts and perceptions – that is why I sometimes prefer the much more specific term of lateral thinking. Not all artists are creative in my usage of the word “creative”. Many artists are powerful stylists who have a valuable style of perception and expression. Indeed, many artists get trapped in a style because that is what the world comes to expect of them. If you employ I. M. Pei, the architect, to design a building for you then you expect an I. M. Pei-type of building. An Andy Warhol piece of art is expected to look like an Andy Warhol piece of art.

Artists, like children, can be fresh and original and very rigid all at the same time. There is not always the flexibility that is part of creative thinking.

Artists can also be much more analytical than most people suppose and artists do take great care with the technology of their work.

It is true that with artists there is a general interest in achieving something “new” as opposed to mere repetition. There is a willingness to play around with concepts and different perceptions. There is a readiness to let the end result justify the process of getting there instead of having to take a sequence of justified steps. All these are important aspects of the general creative mood. There are artists whom I would regard as creative even in my sense of the word and others whom I would not so regard.

The misperception consists of the notion that creativity has to do with art and therefore artists are the best people to deal with teaching creativity.

The second part of the misperception is that an artist (or indeed any creative person) is necessarily the best person to teach creativity. The Grand Prix racing driver is not the best designer of Grand Prix cars or the best driving instructor. There is this notion that through a sort of osmosis the attitudes of the artist will come through to the students who will therefore become creative. I am sure that there is some effect in this general direction but it is bound to be a rather weak effect because osmosis as a teaching process is too ineffectual.

There are some artists who are creative and are good teachers of creativity. These are people who are creative and are good teachers of creativity. They just happen to be artists.

I am not convinced that artists have any special merit in the teaching of creativity that has to do with changing concepts and perceptions.

The confusion of “creativity” with “art” is a language problem that can do considerable damage.

I have mentioned this point before. It is a very important point because much of the so-called “training” in creativity in North America is directed towards “freeing” people up and “releasing” the innate potential for creativity that is believed to be there.

Let me say at once that I fully agree that removing inhibitions, the fear of being wrong, or the fear of seeming ridiculous does have a limited value. You are certainly in a better position to be creative if you are free to play around with strange ideas and to express new thoughts. I would hardly be in favour of inhibition.

The “judgement” system is a very important part of our education as is the notion of the “one right answer” that the teacher has. So attempts to break people out of this mould are worthwhile.

It is precisely this limited value of the “release” idiom that is its greatest danger. There is the belief that that is all that needs doing. So organizations come to believe that if they have got someone to come and “free up” their people, that is all that is needed to develop creative skills. In the same way, “trainers” in creativity believe that creative training is no more than a series of exercises to get people to feel uninhibited and to say whatever comes into their minds.

As I have indicated earlier, the brain is not designed to be creative. The excellence of the human brain is that it is designed to form patterns from the world around us and then to stick to these patterns. That is how perception works and life would be totally impossible if the brain were to work differently. The purpose of the brain is to enable us to survive and to cope. The purpose of the brain is not to be creative. Cutting across established patterns to produce new ideas is not what the brain is designed to do.

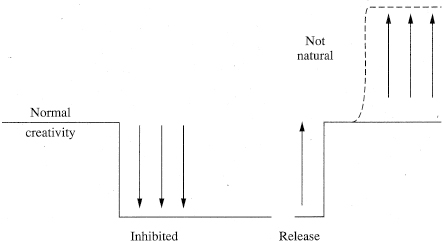

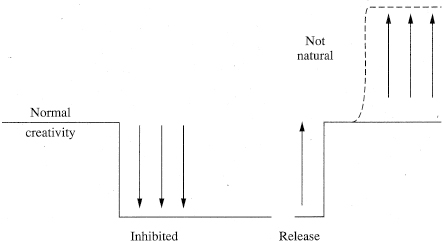

Inhibitions depress us below our “normal” level of creativity as suggested in Figure 1.12. If we remove these inhibitions we come back to our “normal” level of creativity. But to be really creative we have to do some “not natural” things. Such things include the formal processes of provocation to be discussed later in the book.

It is true that some people are creative and that new ideas do occur from time to time. Surely this means that creativity is a natural activity of the brain? That does not follow. New ideas may be produced by an unusual coming together of events. New ideas may be produced by a chance provocation provided by nature (a sort of natural “random word” technique). Furthermore, people get sick from time to time but this does not mean that it is “natural” to be sick. So the fact that some people do have ideas and that ideas do occur does not mean that this must be a natural function of the brain. If it were a natural function then I should expect a very much higher output from natural creativity.

Figure 1.12

Looking at matters purely from the point of view of the behaviour of information systems it is very hard to see how any “memory” system could be creative – except by mistake.

I am often asked about the place of “intuition” in creative thinking. In the English language the word “intuition” seems to have two separate meanings. One meaning implies “insight” and the sudden viewing of something in a new way. This insight aspect is very similar to the humour phenomenon that I mentioned earlier as being the model for lateral thinking. If we do manage to get across to the side-track (see here) then in a flash we see the link-up with the starting point and the new perception is formed. For this meaning of the word “intuition” I would say the purpose of the specific creative techniques is precisely to help us get to this point of insight.

The second meaning of the word “intuition” covers a feeling that is generated from experience and considerations. The ingredients or steps leading to the feeling are not spelled out and so we call it “intuition” rather than “thought”. In the case of previous experience we might find that we have a gut feeling on an issue. In the case of current considerations we feed in factors and then allow “intuition” to work on them to produce an output. Going to sleep on a problem is often cited as an example of this unconscious working of the “intuition”.

The question is whether there is productive mental working which takes place outside our consciousness. Even if this is not the case there can be a sort of reorganization of information which we feed into the mind without any conscious effort to produce a result.

On a theoretical level it seems to me that this is best left as an open question. I suspect that some unconscious reorganization of information and experience does take place, once we feed contexts into the mind. This would hardly be surprising in a pattern-using system that is very prone to insight switching – if you enter a pattern at a slightly different point you can go in a totally different direction (like crossing the watershed between two river basins).

The more important point is the practical level. There is a danger in assuming that it “all happens” in intuition and therefore there is nothing that we need to do about it and nothing that we can do about it. This is a sort of black-box approach which suggests that we abdicate all conscious effort and just hope that intuition does its job properly and when required. Needless to say I am very much against such abdication.

I believe that intuition does play an important part in the final stages of the systematic lateral thinking processes. I believe that from time to time intuition may make a valuable contribution quite apart from any deliberate creative techniques. I think, however, that we should treat these contributions of intuition as a “bonus”. When the contribution is helpful we should be grateful. When there is no contribution we continue to make our deliberate creative efforts.

I have mentioned how the “crazy” aspect of creativity, which is pushed by some practitioners in the field, tends to relegate creative thinking to the periphery as something that cannot be serious.

Craziness is easy to encourage because it seems so different from normal thinking and it can also be fun. People feel their inhibitions slipping away as they compete to be more “crazy” than others in the group.

Obviously, creativity is not going to involve staying within the existing ideas, so any new ideas may, at first, seem crazy when compared with existing ideas. As a result it is very easy to make the false assumption and to give the false impression that creative thinking is based on craziness.

One of the legitimate techniques of lateral thinking is provocation. There is a need to set up a provocation that does not exist in experience and, perhaps, could never exist in experience. The purpose of this is to take us out of the normal perceptual pattern and to place our minds in an unstable position from which we can then “move” to a new idea. This process is deliberate, systematic, and logically based on the behaviour of asymmetric patterning systems. There are formal ways of setting up these provocations: the formal word “po” to indicate that it is a provocation, and formal ways of getting “movement” from a provocation. All this is very different from having a crazy idea for the sake of having a crazy idea.

To explain to students the logical need for provocation and the ways of working with provocations is quite different from giving the impression that craziness is an end in itself and an essential part of creative thinking. As with so many of the points mentioned here, teachers of creativity fasten on this point of “craziness” and set forth to teach it as the essence of the process. This gives quite the wrong impression and puts off people who want to use creativity in a serious manner.

The traditional process of brainstorming sometimes gives the impression that deliberate creativity consists of shooting out a stream of crazy ideas in the hope that one of them might hit a useful target. It is just possible that in the advertising world, for which brainstorming was designed, scatter-gun ideas might produce something useful because novelty is what is being sought. But in almost every other field a scatter-gun approach to creativity makes no more sense than having a thousand monkeys banging away on typewriters in the hope that one of them might produce a Shakespeare play.

If deliberate creativity were no more than a hit-and-miss scatter-gun process then I should have no interest at all in the subject.

What actually happens is quite different. There are the main tracks of perception (see here) which, like river valleys, collect all information in the neighbourhood. Everything flows into the existing “rivers”. If only we can get out of the track or catchment area then we have a high chance of moving into a different catchment area. So far from being a scatter-gun approach, it is more like tearing yourself away from your usual restaurant in a street full of restaurants and so making it easier for you to explore a new restaurant.

There are new ideas waiting to be used if we can but escape from the usual pattern sequence that experience has set up for us. There is a reasonable possibility that such ideas exist and there is a reasonable chance that we might step into them if we but escape from our usual thinking.

Of course, the difficulty is that any valuable creative idea will be perfectly logical – and even obvious – in hindsight, so that the receiver of the new idea will claim that a little bit of logical thinking would have reached the idea without all that “messing about”.

It is said that Western creativity is obsessed with the big conceptual jump that sets a new paradigm, whereas Japanese creativity is content with a succession of small jump modifications that produce new products without any sudden concept change. Which is better?

There is undoubted value in small jump creativity and to some extent the West has ignored this because of the ego-preference for really new and “big” ideas; these are more self-satisfying and more apt to impress others. The Western concern with “genius” creativity has sometimes meant a neglect of “practical” creativity. Small jumps often take the form of modifications, improvements, and combinations of things. The full value of a new idea may depend on a lot of small jump creativity that squeezes the maximum amount out of the innovation.

At the same time, it must be said that a succession of small jumps do not add up to a big jump. A big jump is usually a paradigm change or a new concept. Because this can involve a total reorganization of previous concepts, this is not likely to come from an accumulation of small jumps.

There is a need for both big jump and small jump creativity. It is a matter of balance. Perhaps there needs to be some emphasis on small jump creativity in order to get creativity accepted as a necessary part of the thinking of everyone in an organization. If we look at creativity as only “big jump creativity” then this is seen as only being suitable for research scientists or corporate strategists.

I shall be returning to this point in the Application section of the book.

Because brainstorming has been the traditional approach to deliberate creative thinking, there has grown up the notion that deliberate creative thinking must be a group process. After all, if you sit on your own, what are you going to do? Are you just going to hope for inspiration? The whole idea of brainstorming was that other people’s remarks would act to stimulate your own ideas in a sort of chain reaction of ideas. So the group element is an essential part of the process.

But groups are not at all necessary for deliberate creative thinking. Every one of the techniques put forward in this book can be used by an individual entirely on his or her own. There need not be a group in sight. The formal techniques of provocation (and “po”) allow an individual to create provocative and stimulating ideas for himself or herself. There is absolutely no need to rely on other people to provide the stimulation.

In my experience, individuals working on their own produce far more ideas and a far wider range of ideas than when they are working together in a group. In a group you have to listen to others and you may spend time repeating your own ideas so they get sufficient attention. Very often the group takes a joint direction whereas individuals on their own can pursue individual directions.

It is quite true that the social aspects of a group have a value. It requires a lot of discipline to work creatively on your own. In practice I often recommend a mixture of group and individual work, as I shall explain in the Application section.

I believe that individuals are much better at generating ideas and fresh directions. Once the idea has been born then a group may be better able to develop the idea and take it in more directions than can the originator.

At this moment the point I want to make is that deliberate creativity does not have to be a group process as is so often believed.

There is a classic study by Getzels and Jackson which claimed to show that up to an IQ of 120, creativity and IQ went together, but after that they diverged. Questions need to be asked about the methods used to test intelligence and creativity and also the expectations of the people involved.

People with a high IQ have often been encouraged not to speculate or guess and not to put forward frivolous ideas. This sort of background training can seriously affect the result of any comparisons. The highly intelligent person may know an idea is absurd and so not present it. The less intelligent person may not be smart enough to know the idea can never work and may therefore score a mark for an additional idea.

The practical question is whether you have to be super-smart to be creative, and whether being super-smart might make it more difficult for someone to be creative.

I look at intelligence as the potential of the mind. This may be determined by certain enzyme kinetics which allow faster mental reactions and so a faster rate of scan. This is equivalent to the horsepower of a car. The horsepower is the potential of the car. The performance of the car, however, depends on the skill of the driver. There may be a powerful car which is driven badly and a humble car which is driven well. In the same way, an “intelligent” person may be a poor thinker if that person has not acquired the skills of thinking. A less intelligent person may have better thinking skills.

The skills of creative thinking are part of the skills of thinking but have to be learned directly in their own right. An intelligent person who has not learned the skills of creative thinking might well be less creative than a less intelligent person because some of the thinking skills imparted by education may run counter to creative behaviour (as I suggested earlier). If the intelligent person learned the skills of creative thinking then I would expect that person to be a good creative thinker.

So very much depends on habits, training, and expectations.

I do not think that being highly intelligent need prevent a person from being creative – if he or she has made an effort to learn the methods of creativity.

Above a certain basic level of intelligence I do not believe that a person has to be exceptionally intelligent in order to be creative.