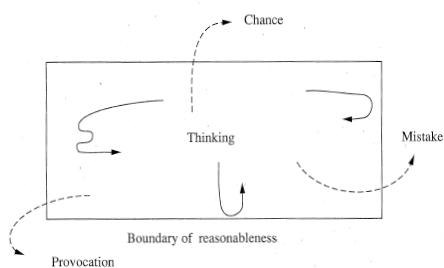

Figure 1.13

IN THIS SECTION I want to consider some of the traditional sources of creativity and also some other sources. These considerations will serve both to place the systematic techniques of lateral thinking in perspective and also to generate some practical points about creative thinking.

Innocence is the classic creativity of children. If you do not know the usual approach, the usual solution, the usual concepts involved, then you may come up with a fresh approach. Also, if you are not inhibited by knowing the constraints and knowing what cannot be done, then you are more free to suggest a novel approach.

When the Montgolfier brothers flew the first hot-air balloon, word of this exciting event reached the king in Paris, who could immediately see the military potential. So he called for his chief scientific officer, M. Charles, and commanded him to produce a balloon. This considerable scientist racked his brains: “How could they have flown this contraption?” After a while he jumped up with the French equivalent of “Eureka”. “They must be using this new gas called hydrogen, which is lighter than air!” he declared. So he proceeded to invent the hydrogen balloon, which is a totally different type of balloon.

Many years ago in the south of Sweden a group of high-school children were brought together by Gunnar Wessman, who was then chief executive of the Perstorp Corporation. I gave them some training in lateral thinking. Then a number of government and industrial figures came down from Stockholm to put problems to the youngsters. One problem involved the difficulty of motivating workers to take the weekend shift in a plant that needed to be kept running over the weekend. In their innocence the children suggested that instead of motivating existing workers it would make sense to have a fresh workforce that always worked only Saturdays and Sundays. Apparently this idea was tried out and the number of applicants for these weekend jobs was far in excess of what was needed. Adults would have assumed that no one would want to do such weekend jobs, that the unions would never permit it, and so on.

Although children can be very fresh and original they can also be inflexible (as I have already mentioned) and they can refuse to put forward further alternatives. The creativity comes from the fresh or innocent approach rather than the seeking for a new approach.

Unfortunately, it is not easy to keep ignorant and innocent as we grow up. Nor is it possible to be innocent in one’s own field. So what are the practical points that we can take from the creativity of innocence?

Perhaps, on certain occasions, we could actually listen to children. The children are unlikely to give full-fledged solutions, but if the listeners are prepared to pick up on principles then some new approaches might emerge.

Some industries, such as retailing and the motor industry, are traditionally very inbred and feel they have all the answers. There is the feeling that you have to grow up in the business to make any contribution. There is a point in such industries looking outwards and seeking ideas from outside. Such ideas may have the freshness that cannot be obtained from insiders no matter how experienced they may be.

A very important practical point concerns research. It is normal when entering a new field to read up all that there is to read about the new field. If you do not do so then you cannot make use of what is known and you risk wasting your time reinventing the wheel. But if you do all this reading you wreck your chances of being original. In the course of your reading you will take on board the existing concepts and perceptions. You may make an attempt to challenge these and even to go in an opposite direction but you can no longer be innocent of the existing ideas. You no longer have any chance of developing a concept which is but slightly different from the traditional concept. So if you want competence you must read everything but if you want originality you must not.

One way out of the dilemma is to start off reading just enough to get the feel of the new field. Then you stop and do your own thinking. When you have developed some ideas of your own then you read further. Then you stop and review your ideas and even develop new ones. Then you go back and complete your reading. In this way you have a chance to be original.

When a person joins a new organization there is a short window of freshness which runs from about the sixth month to the eighteenth month. Before the sixth month the new person does not yet have enough information to get the feel of the business (unless it is a very simple business). After the eighteenth month the person is so imbued with the local culture and the way things should be done that innocent freshness is no longer possible.

It should be noted that some of the most rigid businesses are soft businesses like advertising and television. In some other fields there are fixed regulations or even physical laws to guide behaviour. Because these are virtually absent in the soft fields, the practitioners in such fields invent for themselves a whole lot of arbitrary rules and guidelines in order to feel more secure. If everything is possible then how do you know what to do? So the rigid guidelines become established by tradition and people now find themselves forced to work within these totally arbitrary rules. In such fields innocence is usually dismissed as ignorance.

The creativity of experience is obviously the opposite of the creativity of innocence. With experience we know the things that work. We know from experience what will succeed, what will sell.

The first mode of operation of the creativity of experience is “bells and whistles”. The idea that worked so well before is tarted up with some modifications in order for it to appear as a new idea. This is quite often the sort of product differentiation talked about in classic competitive behaviour.

The second mode of operation of the creativity of experience is “son of Lassie”. If something has worked well before then it can be repeated. If the film Rocky has worked then why not have Rocky II and then III and even IV, V and VI. This strategy covers copying, borrowing, and me-too products. A new style in advertising will immediately spawn many imitators. This type of creativity is very common in North America, where there is considerable risk aversion. If you know that something works then repeat it again rather than try something new. This is because the personal costs of failure are so high. An executive is only as good as his or her last action. This makes for opportunism rather than true opportunity development.

The third mode of operation of the creativity of experience is disassembly followed by reassembly. Things that are known to work are packaged as a product, for example, a financial product. When the time comes to have a new product, the original package is taken apart and the ingredients repackaged in a different way. Usually the ingredients are mixed around amongst different packages so the combinations are always changing.

The creativity of experience is essentially low-risk creativity and seeks to build upon and to repeat past successes. Most commercial creativity is of this sort. There will be a steady and reliable output of moderately successful creativity but nothing really new. If someone were to think of something really new then it would be rejected because there would be insufficient evidence to guarantee the success that is needed. As Sam Goldwyn once said: “What we really need are some brand new clichés.”

The creativity of motivation is very important because most people who are seen as being creative derive their creativity from this source.

Motivation means being willing to spend up to five hours a week trying to find a better way of doing something when other people perhaps spend five minutes a week. Motivation means looking for further alternatives when everyone else is satisfied with the obvious ones. Motivation means having the curiosity to look for explanations. Motivation means trying things out and tinkering about in the search for new ideas.

One very important aspect of motivation is the willingness to stop and to look at things that no one else has bothered to look at. This simple process of focusing on things that are normally taken for granted is a powerful source of creativity, even when no special creative talent is applied to the new focus. This is so important a point that I shall also be dealing with it later under creative techniques.

So motivation means putting in time and effort and attempting to be creative. Over time this investment does pay off in terms of new and creative ideas. A lot of what passes for creative talent is not much more than creative motivation – and there is nothing wrong with that. If we can then add some creative skills to the existing motivation the combination can become powerful.

There is a difference between a photographer and a painter. The painter stands in front of the canvas with paints, brushes, and inspiration and proceeds to paint a picture. The photographer wanders around with a camera until some particular scene or object catches his or her eye. By choosing the angle, the composition, the lighting, and so on, the photographer converts the “promising” scene into a photograph.

The creativity of “tuned judgement” is similar to the creativity of the photographer. The person with tuned judgement does not initiate ideas. The person with tuned judgement recognizes the potential of an idea at a very early stage. Because that person’s judgement is tuned to feasibility, the market, and the idiom of the field, the person picks up the idea and makes it happen.

Although this sort of creativity seems to lack the glamour and ego satisfaction of the originator of ideas, in practice it may be even more important. An idea that is developed and put into action is more important than an idea that exists only as an idea.

Many people who have achieved success with apparently new ideas have really borrowed the beginning of the idea from someone else but have put the creative energy into making the idea happen.

The ability to see the value of an idea is itself a creative act. If the idea is new then it is necessary to visualize the power of the idea. People who develop ideas in this way should get as much credit as those who initiate ideas.

The history of ideas is full of examples of how important new ideas came about through chance, accident, mistake, or “madness”.

Traditional thinking, which is a summary of history, is going along in one direction. Then something happens – which could not have been planned – and this takes thinking out in a new direction and a new discovery is made.

Many of the advances in medicine were the result of accidents, mistakes, or chance observations. The first antibiotic was discovered when Alexander Fleming noticed that a mould contamination of a Petri dish seemed to have killed off the bacteria; thus penicillin was born. The process of immunology was discovered by Pasteur when an assistant made a mistake and gave too weak a dose of cholera bacteria to some chickens. This weak dose seemed to protect them against the fuller dose that was given later.

Columbus only set off to sail westward to the Indies because he was using the wrong measurements. He was using the measurements derived from Ptolemy’s erroneous measurement of the circumference of the globe. Had he been using the correct measurements, which had been worked out by Eratosthenes (who lived in Alexandria before Ptolemy), Columbus would probably never have set sail because he would have known his ships could not have carried sufficient provisions.

In some ways the whole of the electronics industry depended on a mistake made by Lee de Forest. Lee de Forest noted that when a spark jumped between two spheres in his laboratory, the gas flame flickered. He thought this was due to the “ionization” of the air. As a result he proceeded to invent the triode valve (also known as the vacuum tube or thermionic valve) in which the current to be amplified is applied to a grid and so controls the much larger current passing from the filament to the collector plate.

This superb invention provided the first real means of amplification and gave rise to the electronic industry. Before the invention of the transistor all electronic devices used such vacuum tubes.

It seems that the whole thing was a mistake and that the gas flame flickered because of the noise from the spark discharge.

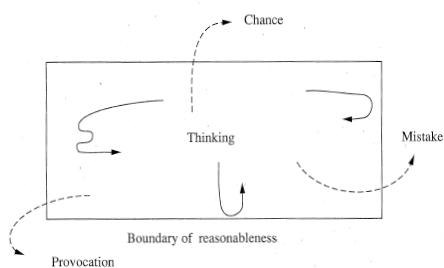

Mistakes, anomalies, things that go wrong have often triggered new ideas and new insights. This is because such events take us outside the boundaries of “reasonableness” within which we are normally forced to work. These boundaries are the accepted summary of past experience and they are very jealously guarded, particularly by people who are themselves rather unlikely to have new ideas.

Apparent “madness” is a source of creativity when someone comes up with an idea that does not fit current paradigms. There is heavy condemnation of the idea. Most of the ideas are mad and do go away. But sometimes the new and mad idea proves to be right and the paradigm has to be changed, but not before there is fierce opposition from the defenders of the old paradigm.

So what is the practical point arising from this powerful source of creativity? Should we make mistakes on purpose?

One practical point is to pay close attention to mistakes and anomalies when things do not turn out as we had hoped.

The second practical point is the deliberate use of provocation. As we shall see later, the techniques of provocation allow us to be mad, in a controlled way, for 30 seconds at a time. In this way we can achieve those boundary jumps that otherwise have to depend on chance, accident, mistake, and madness.

Figure 1.13 suggests how the boundaries of past experience and “reasonableness” turn back our thinking. These boundaries can be jumped by chance, accident, mistake, madness – or deliberate provocation.

There is a further practical point that arises here. Individuals working on their own can hold and develop ideas that are at first “mad” or eccentric and only later become acceptable. If such a person is forced to work with a group from an early stage then it might not be possible to develop such ideas because the “reasonableness” of the group will force the new idea back within the boundaries of acceptability.

Cultures which rely heavily on group work (such as Italy and the United States) may be at a disadvantage in this regard. Countries like the UK, with its tradition of eccentric individuals working away in corners, may have an advantage. Perhaps that is why MITI in Japan found that 51 per cent of the most significant concept breakthroughs of the twentieth century had come from the UK and only 21 per cent from the United States, in spite of the much larger technical investment of the United States.

It has to be said, however, that the complexities of modern science make it much more difficult for individuals to contribute. Cross-disciplinary teamwork may be essential for idea development in the future. Therefore there is an even greater need to develop the deliberate skills of provocation.

In 1970 I suggested to a meeting of oil executives that they should consider drilling oil wells horizontally instead of vertically – and even suggested the use of a hydraulic drilling head. At the time that idea seemed “mad”. Today it is the most fashionable way of drilling for oil as it results in a much higher yield.

Figure 1.13

I have already dealt at length with “style” as an apparent source of creativity. Working within a style can give a stream of new products which are new because they all partake of the same new style.

There is not, however, an individual creative effort for each product except to apply the style. This sort of creativity can have a high practical value but is not the same as the generation of new ideas as such.

I have already commented that in some cases the creativity of artists is the creativity of a powerful and valuable style.

I have also commented extensively on the creativity that is produced as a result of release from traditional cautions and inhibitions. I have noted that this does have a limited value but is not sufficient because the brain is not naturally designed to be creative, so freeing up the brain only makes it a little bit more creative.

It should be said, however, that the change of culture in an organization can lead to a valuable output of creativity. If it is seen that creativity is a game that is permitted and even valued by top management, then people do start to become more creative.

In my experience, when the chief executive in an organization has shown a strong and concrete commitment (not just lip service) to creativity, the culture of the organization can change quite rapidly. Perhaps it is not so much a release from inhibitions but a quick appreciation of new values and a new “game”.

Release from fears and inhibitions is an important part of creativity and will produce some useful results. But by itself it is only the very first stage and is not enough.

The systematic creative techniques of lateral thinking can be used formally and deliberately in order to generate new ideas and to change perceptions. These techniques and tools can be learned and practised and applied when needed.

The tools are directly derived from a consideration of the logic of perception, which is the logic of a self-organizing information system that forms and then uses patterns.

The important practical point is that such techniques/tools can be learned and used. In this way a skill in creative thinking can be developed.

The practical value and importance of the lateral thinking techniques do not, of course, mean that creativity cannot continue to come from other sources as well.