Robert Persons and Edmund Campion took their own safety very seriously. They moved around England, meeting only occasionally. The risks, as Campion had experienced for himself at Dover, were high. In late June 1580 Campion preached in secret at Smithfield in London. A fortnight later he and Persons met other Catholic priests for a conference in Southwark, south of the Thames at London Bridge, in the shadow of the Marshalsea prison and within sight of the Tower. Under the noses of the authorities, Campion also set out on paper the aims of William Allen’s mission as he saw them.

Campion wrote his statement as one of personal intent. ‘My charge,’ he said, ‘is of free cost to preach the Gospel, to minister the Sacraments, to instruct the simple, to reform sinners, to refute errors, and, in brief, to cry alarm spiritual against foul vice and proud ignorance, wherewith my poor countrymen are abused.’ He explained that his Jesuit superiors strictly forbade him ‘to deal in any respect with matters of state or policy of this realm, as those things that appertain not to my vocation’. The Society of Jesus, he wrote, had made a league (that is, an agreement) to carry any cross that Elizabeth’s government chose to lay upon its priests ‘and never to despair your recovery, while we have a man left to enjoy your Tyburn, or to be racked with your torments, or to be consumed with your prisons’. ‘The expense is reckoned,’ he wrote, ‘the enterprise is begun; it is of God, it cannot be withstood. So the faith was planted, so it must be restored.’

The letter was beautifully composed, poised and articulate, an elegant statement of belief and mission – so much so, in fact, that it instantly outgrew its original purpose. Campion prepared the letter for Elizabeth’s Privy Council, to be sent only in the event of his capture. The fact he left it unsealed meant that very quickly copies of it began to circulate, passing secretly between English Catholics. Campion’s defence was, after all, a crafted weapon to be used in an extraordinary propaganda war. By October 1580 Robert Persons and a printer called Stephen Brinkley had set up a secret printing press a few miles out of London. Later, because of the danger of discovery, Brinkley and his assistants had to move it to a house in Oxfordshire. So Persons and Campion were able to speak to English Catholics in books secretly printed, bought and borrowed, while the two Jesuits, with other priests, moved around England to preach, say mass and hear confessions.

John Hart, the passionate preacher Charles Sledd had heard in Rheims and now a prisoner, was moved from the Marshalsea to the Tower of London at Christmas 1580. There he joined Sledd’s former companions Robert Johnson, Thomas Cottam, Ralph Sherwin and Henry Orton. Luke Kirby, the friend of Anthony Munday at the English College in Rome, was held in the Tower also. The four priests and Orton had been there since 4 December.

The Elizabethan antiquary John Stow described how the Tower of London was at once ‘a citadel, to defend or command the city’, a royal palace, a ‘prison of estate, for the most dangerous offenders’, a royal mint, an armoury, a treasury for the queen’s jewels and an archive for the courts of justice at Westminster. A contemporary of Stow’s wrote that the judicial purpose of the Tower was ‘to discover the nature, disposition, policy, dependency, and practice’ of offenders against the queen. The priests and other prisoners were guarded by thirty yeoman warders under the authority of a lieutenant, Sir Owen Hopton, a man of about sixty who had been in post for ten years.

The Tower of London was surrounded by a wide moat fed by the River Thames. Rising high above every other building was the White Tower, built by William the Conqueror in the eleventh century. Great defensive walls ran between the various towers and gates. St Thomas’s Tower stood over the water gate to the Thames, near the wharf dividing the moat from the river. In the inner ward between the Beauchamp Tower and the Devereux Tower was the church of St Peter ad Vincula. Near the lieutenant’s lodging, which was in the south-east corner of the inner ward, stood the Bell Tower. Close to that was the main gate, from which one crossed the moat to the Middle Tower, on to the Lion Tower, and out to the city of London. Anyone lucky enough to be able to leave the fortress when the bell rang went from the Lion Tower through the bulwark gate and on to Tower Hill, looking north to the executioner’s scaffold and east to Tower Street. Prisoners were often kept in the Beauchamp, Broad Arrow, Salt and Well Towers. Those who could not pay for their own lodging, fuel and candles were supported by the crown. Owen Hopton carefully kept and signed the accounts. Prisoners often carved their names into the stone of the walls. One man, James Typpyng, left an inscription in the Beauchamp Tower: ‘Typpyng stand or be well content and bear thy cross for thou art [a] sweet good Catholic but no worse’. Cottam, Hart, Johnson, Orton and Sherwin, kept in close confinement and frequently interrogated, left no marks on the walls of their chambers.

The priests were questioned about their loyalty and allegiance. The official record of what Ralph Sherwin said in his examination on 12 November 1580 is short, even blunt. Did he believe Pope Pius V’s bull of excommunication against the queen to be lawful? Sherwin refused to answer the question. Was Queen Elizabeth his lawful sovereign, and should she continue to rule in spite of the Pope? Sherwin would not say. This interrogatory was put to him a second time. Knowing that he risked a charge of high treason for his answer, he prayed not to be asked any question that put him in danger. To Sherwin, in fear of his life, the questions were obvious traps in which he was caught however he answered. To his interrogators, the priest refused to answer plain questions about his loyalty as the queen’s subject. They drew their own conclusions.

Not surprisingly, the priests’ interrogators returned again and again to Pope Pius V’s bull Regnans in excelsis, of 1570, by which Pius had denounced Queen Elizabeth as a bastard heretic schismatic and excommunicated her from the Catholic Church. John Hart was questioned about the bull. His interrogators knew that Pope Gregory, who supported the priests’ mission to England, had confirmed Pius’s bull. They knew, too, that only a few months earlier, in April 1580, Gregory himself had given the ‘faculties’ of this confirmation to Robert Persons and Edmund Campion in Rome.

Hart told his interrogators that Pius’s bull was still lawful. But he explained that Gregory had understood the difficulty faced by English Catholics who were caught between a Pope who commanded them not to obey the queen and their loyalty to Elizabeth. As Hart put it: ‘if they obey her, they be in the Pope’s curse, and [if] they disobey her, they are in the Queen’s danger’. And so Pope Gregory’s dispensation allowed Elizabeth’s Catholic subjects to obey her without putting their souls in peril. For Catholics this was potentially the untying of a very difficult knot. Significantly, however, Elizabeth’s government did not see Pope Gregory’s dispensation as any relaxation of Regnans in excelsis. In fact they took Gregory’s action as proof that Persons and Campion had been charged to enforce Pius’s bull against someone whom the Pope believed to be a heretic queen. Whatever they might say about their pastoral work as priests, as agents of the Pope their object (in the view of Elizabeth’s government) was a political one.

On 31 December 1580, when he spoke of Pope Gregory’s dispensation for English Catholics, John Hart was threatened with torture. Otherwise he, like Ralph Sherwin, may have chosen silence as the best course. Hart was taken to see the rack, the principal instrument of torture in the Tower, a large frame containing three wooden rollers to which the prisoner was bound by his ankles and wrists. The rack’s purpose, simply and terribly, was to stretch the human body until it began to tear apart. The middle roller, which had iron teeth at each end, acted as a kind of controlling lock. This meant that the prisoner could be questioned while experiencing a constant amount of pain. It was probably a fairly simple device for even one man to operate. A number of officials, called commissioners, were present when a prisoner was tortured, of whom the lieutenant of the Tower was always one. Sometimes a clerk of the Privy Council would attend, often the man who had brought the torture warrant from the Council to the Tower. Lawyers, with their skills of taking and evaluating evidence, also served as commissioners.

Many Elizabethans would have associated torture with the terrible practices of the Spanish inquisition, or the Catholic persecution of Mary I. John Foxe’s great ‘Book of Martyrs’, Acts and monuments, had one woodcut of the racking of a Protestant prisoner in Mary’s reign. But the use of torture by Elizabeth’s government became common in the 1580s. Some principles of its use were set out in a short pamphlet printed by the royal printer in 1582. The author of this official defence of torture was Thomas Norton, a London lawyer in his early fifties called so often to the Tower to interrogate priests on the rack that his enemies gave him the nickname ‘Rackmaster Norton’. Three of Norton’s principles were that a prisoner was only ever tortured on the authority of a warrant signed by at least six members of the Privy Council; that no one was tortured for his faith or conscience; and that only a guilty man was ever put to torment. Norton’s Catholic enemies hardly believed him. William Allen recounted the supposed exchange between Norton and John Hart in the racking chamber:

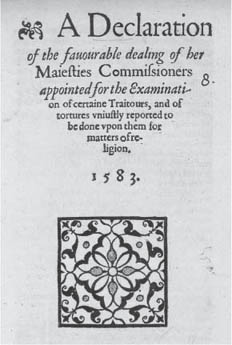

The title page of Thomas Norton’s public defence of torture, 1583.

And when Master Hart was taken from the rack, the commissioners talking with him after a familiar manner: Norton asked him, saying, ‘Tell truly, Hart, what is the meaning of the coming in of so many priests into England?’ Who answered, ‘To convert the land again to her first Christian faith and religion, by preaching and peaceable persuasion, after the manner that it was first planted.’ To which Norton said: ‘In my conscience, Hart, I think thou sayest truth.’

Allen’s words suggest something of the sharpness and seriousness of the ideological clash between Elizabeth’s government and its Catholic enemies.

For Elizabeth’s government priests like John Hart were agents of a foreign power whose object was to remove a lawful monarch from her throne. They were traitors, and their torture was a necessary act of state. Thomas Norton wrote that no man ‘was tormented for matter of religion, nor asked what he believed of any point of religion, but only to understand of particular practices for setting up their religion by treason or force against the Queen’. The words in emphasis are critical: the full force of the law was being used against the means by which the Catholic faith was going to be brought back to England – by sedition, rebellion and invasion – and not against the faith itself. Catholic writers like Doctor Allen responded that this was simply a lie: theirs was a pastoral mission to save the souls of English Catholics in the face of vicious persecution, with the hope of turning England away from heresy and schism. Catholics likened Elizabeth’s government to the authorities of ancient Rome who had persecuted early Christians, calling the queen’s ministers ‘atheists’ and ‘politiques’.

By early 1581 Edmund Campion’s brilliant and articulate defence of his mission was being read and passed around by people sympathetic to the Catholic cause. The authorities called it ‘Campion’s brag’. It was a formidably persuasive, even an incendiary, piece of writing. One case reported to the justices of Southampton, and by them in turn to the Council, illustrates how influential it was. One William Pittes was alleged to have said that ‘great cruelty was used at this present by imprisoning of good men, whom he termed Catholics, affirming the prisons to be full of them in every place’. He thought Elizabeth ‘was deceived, and erred from the true faith’. His daily prayer was to bring her to the Catholic faith. Pittes asked a man called Lichepoole whether he had seen a copy ‘of a challenge made by one Campion’. Lichepoole had not, so Pittes ‘immediately pulled out of his purse the copy of the said challenge, and read it unto the said Lichepoole, promising him a copy of the same’. The copy was made and delivered as Pittes had promised. This was the power of Edmund Campion’s pen: he was proving a skilled and elusive general in the long war for hearts and minds, and a formidable enemy to Elizabeth and her government.

So dangerous, in fact, was ‘Campion’s brag’ that it had to be answered officially. Here Elizabeth’s government ran the obvious danger of making Campion’s letter even more widely known and read than it was already, but this was a risk the authorities were willing to take. One pamphlet was by William Charke, a combative Protestant controversialist, and it came off the press of Christopher Barker, the queen’s printer, on 17 December 1580. Charke wrote of Campion’s ‘insolent vaunts against the truth, joined with words pretending great humility’. Another attack came a month later from an Oxford theologian called Meredith Hanmer. He too exposed Campion’s deceit, ‘where one thing is said in word, and the contrary found in practice and deed’. Campion, he wrote, had set the mother against her own son, the son to take armour against his father, the subject against the prince: ‘He hath deposed kings and emperors, he translated [altered] empires, he treads upon princes’ necks, he takes sceptres and crowns from kings’ heads, and trampleth them under foot.’

The fierceness of the attacks by Charke and Hanmer shows that Campion had the power to make his words felt, even if he himself could not be found. And all the time the temperature of the debate was rising. On 10 January 1581 a royal proclamation ordered the return of all English students from foreign seminaries and the arrest of all Jesuits in England. The intent and purpose of the seminaries, it said, was to pervert the queen’s subjects in matters of religion and ‘from the acknowledgement of their natural duties unto Her Majesty’. Young English Catholics had been made ‘instruments in some wicked practices tending to the disquiet of this realm … yea to the moving of rebellion’. A new law made it high treason for a priest to absolve Elizabeth’s subjects from their obedience to the queen and to reconcile them to Rome, even without a bull or other document from the Pope.

Laws like this so well expressed the sense of emergency and danger gripping Elizabeth’s ministers. Their consequence was that political loyalty to crown and government became impossible to disentangle from loyal worship in the Church of England. This was why the words of William Pittes concerning the cruelty used against Catholics and his prayer for Elizabeth’s conversion to the Catholic faith were overtly political. What Pittes said and did was described by the justices of Southampton as a ‘matter of offence against the state’ and government. Pittes survived his brush with the authorities. He may even have been the same William Pittes who in 1584 went off to William Allen’s seminary in Rheims. Was he inspired by Campion? To Elizabeth’s advisers the priests both in London’s prisons and at large – and potentially also ordinary Catholics throughout England – presented a clear danger. Disturbingly persuasive, men like Campion were political agents of a dangerous and obviously hostile foreign power.

Not surprisingly, Campion was sought with ever-increasing urgency. He was always moving, always in disguise. He wrote in a letter: ‘I am in apparel to myself very ridiculous. I often change it and my name also.’ Between Christmas 1580 and Easter 1581 he travelled through Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire, Yorkshire and Lancashire. At the end of March 1581 he delivered a manuscript to Stephen Brinkley’s printing press in Oxfordshire. Campion called it Rationes decem (Ten Reasons) and in it he set out Catholic faith and tradition. On 27 June four hundred copies of this very slim pamphlet were laid out on the benches of St Mary’s church in Oxford for the scholars to read on the day they gathered to defend their theses. Done right under the noses of the authorities of his old university, it was an audacious publicity coup for Campion. Elizabeth’s government was deeply unsettled. The priests were being pursued with energy and urgency. Eleven days before the scholars of Oxford read Campion’s Ten Reasons, Robert Persons wrote secretly from London to the rector of the English College in Rome that ‘Sledd is on our track more than others, for he has authority from the royal council to break into all men’s houses as he will and to search all places, which he does diligently, wherever there is a gleam of hope of booty.’

Some time after Midsummer 1581 Maliverey Catilyn, one of Sir Francis Walsingham’s agents, was posing as a good Catholic somewhere near the Sussex coast. Catilyn’s speciality, as the coming years would show, was to go into prisons to spy on inmates, reporting their plots, schemes and conversations. His world was the Catholic underground, where he was well connected and trusted.

A Catholic view of Elizabethan persecution by Richard Verstegan, 1592: lay Catholics and a priest are arrested and imprisoned.

Catilyn explained to Walsingham by letter that he had met some bad men, yet one now came to travel with him ‘who exceedeth all the rest’. The man, whose name he did not give, ‘greatly pitied my case’: presumably Catilyn, playing the poor Catholic, had told him a tale of woe. The man was careful, and he had refused to talk to Catilyn in the busy port town of Portsmouth. He was a sailor or the owner of a boat. He had been in France at Christmas, and in March 1581 he had brought back to England a priest called John Adams. Adams, as Catilyn knew, had been arrested at Rye and sent to Walsingham to be examined. The man had a brother (or a brother-in-law) ‘on the other side’ who called himself Richard Thomas but whose real name was Gyles Whyte, from whom, Catilyn wrote, ‘he receiveth letters and books for his friends three or four times every year and they see things are conveyed to another brother that he hath dwelling with a merchant at Billingsgate called Cox’. On his last journey Catilyn’s new contact had brought back to England three Agnus Deis, small cakes of wax stamped with the symbol of the lamb of God and blessed by the Pope. One was for the shipmaster’s wife, the second was for his mother and the third was for his sister. At Midsummer he had helped another priest to land secretly in England at Stokes Bay near Portsmouth, and given him directions on what course he should take. He also had in his keeping, Catilyn wrote, some jewels belonging to Edmund Campion: Campion, after all, had come into England disguised as a Dublin jeweller.

Maliverey Catilyn apologized to Walsingham for having to end his letter quickly. His new contact was near by. ‘He is here with me,’ Catilyn wrote, ‘and therefore I think your honour would do well to see him.’ Catilyn pardoned his scribbling. His companions, he said, ‘cry to me for speed’, for they wanted to be in London that night, ‘and for the avoiding of suspicion I dare not be tedious’.

In early July Edmund Campion and Robert Persons were in Oxfordshire. On Tuesday, 11 July they parted. Campion and a fellow priest set out north for Lancashire. They would then travel to Norfolk. Persons and his man set off towards London, but before long Persons heard Campion galloping after him with a request to go instead to Lyford Grange in Berkshire, the house of Master Francis Yates, a prisoner in Reading jail, who had written to Campion to ask him to visit his family. Persons reluctantly agreed to Campion’s detour, but he instructed him to stay at Lyford Grange for no more than a day, or one night and a morning. Campion did just that. The mistake he made was to return to the Grange a day later.

This was on 14 July, a Friday, the same day that two royal officials left London. Their names were David Jenkins and George Eliot and they carried a warrant ‘to take and apprehend, not any one man, but all priests, Jesuits, and such like seditious persons’ that they should meet on their journey. They had decided to ride to Lyford Grange, a known Catholic house, where they thought they might discover priests. They wanted to arrive there at about eight o’clock on the morning of Sunday the 16th.

Jenkins was a pursuivant, a messenger of the queen’s chamber. Wearing Her Majesty’s livery, pursuivants executed warrants from the queen and her Privy Council. In the 1580s they were busy hunting for priests in London and putting Catholic recusants in prison. At times it was a dangerous job for which some pursuivants found financial compensation in bribery and corruption, either paid for letting people go or seizing the money of those they arrested. With men like Charles Sledd working with the pursuivants, they did not enjoy a high reputation.

The same could be said of George Eliot, Jenkins’s companion on their journey to Lyford Grange, who called himself by the grand title of ‘yeoman of Her Majesty’s chamber’. He had recently recanted his Catholic faith, confessing ‘the grievous estate of his life’ to one of Elizabeth’s most trusted and senior advisers, the Earl of Leicester. Eliot offered evidence of his good will. This was information, for having served in Catholic gentry houses in Essex and Kent, he was able to name names. Eliot did what Sledd had done in Rome, though less comprehensively: he compiled a catalogue of every Catholic gentleman and gentlewoman he knew in eight counties in England.

Eliot did something else which was irresistible in the emergency years of the early 1580s: he revealed the existence of a terrible conspiracy against Elizabeth and her ministers. Eliot told the Earl of Leicester of a plot to murder the queen and her leading councillors. He said that behind it all was a priest called John Payne, trained at Douai and ordained a priest in 1576, whom Eliot had known in Essex. Chief names were those of the Earl of Westmorland, rebel and outlaw, and William Allen. The plan was for fifty armed men, all paid for by the Pope, to assassinate Elizabeth while she was touring her kingdom on progress. Five men would kill the queen, while three groups of four would ‘destroy’ Leicester, Lord Burghley and Sir Francis Walsingham. Leicester gave the paper to Burghley, who calmly noted in the margin ‘Payne to be examined’. Eliot also had information on how Catholic books were being sold secretly by two bookbinders in Paul’s Cross churchyard. True or not, Eliot spoke to the anxiety of the moment. London was buzzing with news of books and pamphlets by and against the Jesuits. Eliot was believed, and by the early summer he set to work to infiltrate Catholic families he had not long before served.

Eliot was sure that he and Jenkins would find priests concealed at Lyford Grange. Thomas Cooper, whom Eliot had known in Kent, was Master Yates’s cook at Lyford. Through Cooper they could enter the Grange without causing suspicion. Once in the house, they would conduct a search. Their plan was as simple as that. They had no idea that they would find at Francis Yates’s house the most wanted man in England.

Jenkins and Eliot arrived at Lyford Grange on Sunday, 16 July at about eight in the morning, just as they planned. They found outside the gates of the house a servant who seemed to Eliot ‘to be as it were a scout watcher’. Eliot spoke to the servant, asking after Thomas Cooper, who came out to meet him and Jenkins. Eliot told Cooper a tale. He said that he was travelling into Derbyshire to see friends but had come far out of his way to Lyford because he longed to see him. Cooper invited him to the buttery for a drink. The cook asked Eliot about his friend, Jenkins, ‘whether … he were within the Church or not, therein meaning whether he were a papist or no’. Eliot answered that Jenkins was not a Catholic, but that he was a very honest man. Leaving Jenkins in the buttery, Cooper took Eliot through the hall, the dining parlour and other rooms to a ‘fair large chamber’. There he found three priests, of whom one was Edmund Campion. Also in the room were three Brigitine nuns (not as politically dangerous as priests but still illegal) and thirty-seven other Catholics. Eliot, committing to memory the faces and clothes of members of the congregation, heard Campion say mass. Then Campion sat down in a chair beneath the altar to give a sermon that lasted for nearly an hour, ‘the effect of his text being, as I remember, that Christ wept over Jerusalem etc. and so applied the same to this our country of England, for that the Pope his authority and doctrine did not so flourish here as the said Campion desired’.

At the end of Campion’s sermon Eliot rushed down to find Jenkins in the buttery. He told Jenkins what he had seen, and they both left the house to summon help. They found it in the person of a local justice of the peace called Master Fettiplace, to whom they showed their commission. Within a quarter of an hour Fettiplace had gathered forty or fifty armed men, who went off with speed to Lyford Grange. It was at about one o’clock in the afternoon when they knocked at the gates. They were kept waiting for half an hour. At last there appeared Mistress Yates, five gentlemen, one gentlewoman and three nuns. The nuns were now dressed as gentlewomen, but Eliot remembered their faces. The gates were opened, and Eliot, Jenkins and the other men began to search the house, in which they found ‘many secret corners’, and also in the densely planted orchards and hedges and the ditches of the Grange’s moat. The searchers discovered Francis Yates’s younger brother hiding in a pigeon house with two companions. But they could not find Campion and the two other priests. It was nearly evening when Eliot realized they needed more help, and so he sent messages to the high sheriff of Berkshire and another local justice of the peace. The sheriff could not be found, but the justice, Master Wiseman, came quickly with ten or twelve of his servants, and the search continued into the night.

Early on Monday morning, the 17th, further help arrived. Christopher Lydcot, a third Berkshire justice, came to Lyford Grange with a large group of his own men. At ten o’clock the priests had still not been found. But the persistence of the searchers paid off, and it was David Jenkins the pursuivant who ‘espied a certain secret place which he found to be hollow’. With a metal spike he broke a hole in the wall, ‘where then presently he perceived the said priests, lying all close together upon a bed, of purpose there, laid for them, where they had bread, meat, and drink, sufficient to have relieved them, three or four days’. In a loud voice Jenkins called out, ‘I have found the traitors.’

Campion and his fellow priests were put under heavy guard. Along with six gentlemen and two husbandmen they were taken from Lyford Grange to Abingdon on Thursday, 20 July, and to Henley upon Thames the following day. At Henley, Eliot, Jenkins, Master Lydcot and Master Wiseman received instructions from the Privy Council to stay at Colnbrook, about twenty miles west of London, on Friday night, the 21st. They entered London on Saturday, processing through the city to the gate of the Tower of London, where Campion and the others were put into the custody of its lieutenant, Sir Owen Hopton. Eyewitnesses told Robert Persons, still secretly in England, that Campion was mounted upon a very tall horse with his hands tied behind his back, and his feet strapped together under the horse’s belly. An inscription was put round his head: ‘Edmund Campion, the seditious Jesuit’.

There was a rush to the printing press. One printer lost no time at all, going to the Bishop of London and the Stationers’ Company for a licence to print a pamphlet called ‘Master Campion the seditious Jesuit is welcome to London’. He paid four pence for the licence, which he received on 24 July, by which time Edmund Campion had been in the Tower for barely forty-eight hours. Within days the enterprising Anthony Munday, that young man who had lived in the English College in Rome but knew nothing of Edmund Campion, rushed into print with a breathless (and as it turned out wholly inaccurate) account of Campion’s capture, in which Master Jenkins the pursuivant and the sheriff of Berkshire were the heroes. We can imagine eager customers visiting William Wright’s shop next to St Mildred’s church in the Poultry – ‘the middle shop in the row’ – to buy Munday’s story fresh from the press.

To Catholic writers Campion’s story was a heroic tale of martyrdom, sacrifice and persecution. William Allen called it a ‘marvellous tragedy … containing so many strong and divers acts, of examining, racking, disputing, treacheries, proditions [treasons or treacheries], subornations of false witnesses, and the like’. Allen’s mission to save England from heresy and Catholics from their persecutors became the subject of sharp exchanges between Campion’s friends and enemies. One of the most energetic of these writers was Anthony Munday, who, after recognizing the mistakes of his first account of Campion’s capture, collaborated with George Eliot in writing and publishing the definitive account. Eliot had come to Munday’s lodgings in the Barbican and had written and then signed a statement of what had really happened. In these months – between July 1581 and April 1582 – Munday busily answered Doctor Allen’s powerful books and pamphlets. Munday, the spy turned writer, relished every encounter with the Catholic enemy.

In fact the characters of Munday and his fellow intelligencers, Charles Sledd and George Eliot, were very much tied up with the story of Edmund Campion’s capture. Reputations were at stake; the truth was contested. Both sides in this battle – Allen in Rheims, in London Munday, with Sledd and Eliot forced out of the shadows – fought to establish the facts as they saw them. Everything they wrote crackled with the powerful electricity of belief and emotion, blurring fact and fiction. There were, for example, two published accounts of what Campion had said to George Eliot in the days of the journey from Lyford Grange to the Tower of London. Eliot’s version hinted strongly at a threat to his own life:

Campion when he first saw me after his apprehension, said unto me, that my service done in the taking of him would be unfortunate to me. And in our journey towards the Tower, he advised me to get me out of England for the safety of my body.

Was it then a coincidence that Eliot had fallen sick at his lodgings in Southwark? The goodwife of the house in which he was staying knew nothing about her lodger till a Catholic widow told her that it was Eliot who had arrested Campion. He wrote that ‘the papists take great care for me, but whether it be for my weal or woe … let the world judge’. Eliot believed that he was a marked man.

Allen’s account of what Edmund Campion said and how he behaved was very different to Eliot’s recollection. Already he was making Campion a model of Catholic patience and forgiveness in the face of terrible persecution. Allen would have had very little idea of what really passed between Eliot and Campion on the journey from Lyford Grange to London. His words were meant instead as an inspiration for Catholics:

Eliot said unto him, ‘Master Campion, you look cheerfully upon every body but me; I know you are angry with me in your heart for this work.’

‘God forgive thee Eliot’, said he, ‘for so judging of me: I forgive thee, and in token thereof I drink to thee, yea, and if thou wilt repent and come to confession I will absolve thee: but large penance thou must have.’