In June 1580 William Parry, Lord Burghley’s gentleman intelligencer, was in Paris, spying on the city’s English Catholics. Knowing he could be useful, he sought Burghley’s patronage and favour. In his leisured way Parry gathered information without any great finesse, something that troubled Elizabeth’s ambassador in Paris, Sir Henry Cobham, who wrote rather uncertainly to Burghley that an Englishman called Master Parry pretended to depend upon his lordship’s good favour.

Parry took it upon himself to work as an intermediary between Elizabeth’s government and some of the exiles. He spied on the English Catholic nobility and gentry visiting Paris and sought to befriend them. He sent reports to London interceding on their behalf. Sometimes he came close to making deals with them, negotiating favourable terms for their loyalty. There was a purpose to this that Parry, dazzled by his own self-importance, did not recognize. Elizabeth’s government was pragmatic about the exiles. They could be won over or they could be divided against themselves, reputations compromised in the eyes of other Catholics by their negotiations with the government. Here Parry – clever, indiscreet and self-absorbed – was the perfect instrument. He was quite serious when he wrote to Burghley on behalf of Sir Thomas Copley, a prominent English Catholic gentleman. Parry praised Copley’s family and descent, and noted Copley’s satisfaction at Burghley’s continued ‘goodness and friendly mind towards him’. Copley, Parry wrote, took it ‘very grievously that Her Majesty (to whose person and state he always protested so true and so loyal a heart) should by sinister information conceive such mislike of him’. Parry was confident that he had divined Copley’s true loyalty: ‘In truth, my lord, it seemeth to me that he meaneth good faith and very sincerely and unfainedly to give Her Majesty all the contention he can, and faithfully to serve the same to the uttermost of his ability.’

Sir Thomas Copley was a fairly harmless exile. The Earl of Westmorland, outlaw and rebel, was not. But still Parry wrote on Westmorland’s behalf to Burghley. Westmorland, who was twenty-six or twenty-seven when he had taken part in the Northern Rising of 1569, was now ready to fall at Elizabeth’s feet, repenting the errors and faults of his youth. Only here in Parry’s report to Burghley there was just a shade of uncertainty. He did not know whether ‘the reclaiming of desperate men do agree with our state and policy’ – this certainly suggests the limit of any instructions Burghley had given to him – but he saw the benefits of it and left the matter to Burghley’s ‘wisdom and grave consideration’.

Even William Parry may have recognized that these were treacherous waters, but he was unselfconsciously happy to navigate them. He had standing, unofficial yet acknowledged. One mark of his credit in official circles was to receive letters from Burghley. A second was his freedom to send a letter to England with Edward Stafford, Elizabeth’s special ambassador to the Duke of Anjou, which Stafford delivered to Burghley at Elizabeth’s court. This letter contained a digest of a fortnight’s worth of intelligence from Paris in July: the politics of the Pope’s cardinals, a book printed in Paris slanderous to Elizabeth, the thinking of William Allen, the Bishop of Ross’s standing with the Archbishop of Glasgow (both men were representatives in Paris of the Queen of Scots), and even an account of dinner with the archbishop and two Scottish noblemen. To Lord Burghley Parry was a moderately useful source of information. His cleverness and vanity worked to his advantage – for the time being.

In September 1580 Parry was in London. He would have preferred to speak to Burghley at court but had to settle for a letter. Burghley was too busy to see him. ‘Your lordship’s small leisure maketh me loath to deliver many things by mouth,’ he wrote, ‘my letters serving for your better leisure.’ He recommended the service of Guido Cavalcanti, an agent of Catherine de’ Medici, and enclosed a letter he had come across in Paris. It was the work of ‘a busy dealer in English practices’, an Italian called Julio Busini.

Parry was pompously self-important in writing to Burghley. He related his many conversations with the French ambassador in London, who, Parry said, talked to him plainly about great and significant things. He boasted about his contacts with Mary Stuart’s advisers in Paris: the Archbishop of Glasgow, the Bishop of Ross and, most mysterious of all, Thomas Morgan, Mary’s gatherer of secret intelligence. Parry was always alert to Lord Burghley’s powerful patronage: he was, he wrote, merely the poor sworn servant of the queen and looked upon Burghley as his best friend, father and lord. Parry was a man rarely given to understatement. But the truth was that Parry the social climber had long lived the kind of life he could not afford to sustain. The easy flatterer was heavily in debt. Soon he would feel the reality of the situation he had made for himself.

The great fall came for Parry in early November 1580. On Wednesday the 2nd he forced his way into a chamber in the Inner Temple in London and confronted Hugh Hare. Hare was both a lawyer and a moneylender who had lent Parry the huge sum of £610, with interest to pay on top. Hare said that Parry broke down the door to his rooms and threatened to kill him. Parry’s account was very different. Picking through the depositions of witnesses, he contended the evidence. The broken door and the threat to Hare’s life, for example, came from Hare’s evidence only, or so Parry maintained. One witness had gone up to Hare’s chamber to find ‘the nail of the latch of the door thrust out’, but he could not say that Parry had done this. The same witness seems to have deposed that Parry had no weapon. Another said in his deposition, according to Parry, that ‘no harm had happened if Hare had not threatened to put Parry in a sack’. The threat, then, came from Hare. Carefully and precisely – and no wonder, for his life was at stake – Parry set out in a letter to Lord Burghley the weakness of the evidence against him, even questioning the literacy and accuracy of his indictment. The case went to trial, but Parry, always given to feelings of betrayal by others, believed that it was a fix: ‘It will be proved that the recorder [i.e. the most senior judge in London] spake with the jury. And that the foreman did drink.’ Whatever the truth of his allegations, Parry was found guilty of burglary and attempted murder.

The Elizabethan punishment for a felony was hanging. But Parry, pardoned by the queen, was saved from the gallows: after all, in Lord Burghley he had a powerful patron. Yet he was nevertheless still deeply, painfully in debt. The sum of £610 he had borrowed from Hare had risen ‘by usury and recompence’ (to use Parry’s words) to £1,000. To add to the money he owed to Hare was the fantastic sum of £2,000 in a bond of surety.

But Parry was a survivor, even if there was something reckless in the way he tried to raise money. He became in effect a confidence trickster, working to ingratiate himself with a young heir called Edward Hoby. Parry, clever and plausible, was facing financial ruin: Hoby, who was twenty-one years old, was young, rich and inexperienced. He was also Lord Burghley’s nephew, and in November 1581 Hoby’s mother, Lady Russell, wrote to her powerful brother-in-law ‘in my extremity of grief for a matter of no small importance to my heart’. She had heard of Parry’s ‘ill dealing’ used towards her son ‘in compassing bargains at his hands’ concerning some of Hoby’s properties. Parry had given his oath to Lady Russell. He had broken it, and she was desperate: ‘if this be not prevented the boy is undone. I beseech your lordship most humbly off my knees, good lord commit Parry to some prison’. It seems that Burghley did exactly that, for by the middle of December Parry was in the Poultry Counter in London, a filthy prison between Old Jewry and the Royal Exchange, not far from Cheapside. There he reflected upon the debts he owed to Hugh Hare, with no prospect of a handsome fee from Edward Hoby.

To Parry it was obvious that he was the wronged party. He wrote to the Privy Council, ‘driven by this extraordinary mean’ to petition for redress of the grievances done to him by Hare. He craved their lordships’ favour and desired justice. He was very angry: ‘God knoweth and my conscience beareth me witness that I have deserved better of my prince and country than to be thus tormented in prison and credit by a known cunning and shameless usurer.’ These were strong words to use for a man in Parry’s position.

Twelve men had stood surety for Parry, together raising the necessary bond for good behaviour of £2,000. It was clear he had influential and rich friends. One of the guarantors was Edward Stafford, soon to be Elizabeth’s resident ambassador at the French court; on one level at least Parry must have been a persuasive man. Yet his difficulties continued. In late January 1582 Parry wrote again to Burghley. Those ‘best friends’ of his who had been willing to be bound to Hugh Hare for £600 were, he said, ‘by the practise of my adversaries drawn from me’. Parry could rely only upon Burghley to ‘stand my good lord’. If Burghley did nothing, Parry was ‘like to lie here a good while’ in what he called his ‘bad lodging’ in prison. So Parry, the traveller and intelligencer, made a suggestion to Burghley: ‘If my absence at Paris for three years may do any service to your lordship (thereby also to avoid the offence of all men here) I will gladly undertake it.’ His ‘singular devotion’ to Burghley and resolution to honour and serve him made Parry ‘thus bold’. He wanted, in other words, once again to spy for Burghley: it was the price he offered to pay for his release from prison.

Burghley seems to have accepted Parry’s offer. Freed from the Poultry Counter, in early August 1582 he prepared to set out for Paris. He stayed in the city for just over a month, leaving for Lyons on 25 September. By January 1583 he was in Venice. He appeared now supremely untroubled by any obligation to Burghley: the urgency of the Poultry Counter was soon swept away by the pleasures of travelling through France and northern Italy. He had clear ideas already about what he did and did not want to do for Elizabeth’s lord treasurer. After all, he was no ordinary informant; he knew he had special talents. ‘I find it a matter very unpleasant to be troubled or tied to the advertisement of ordinary occurents,’ he wrote. If anything happened that he thought was of importance, Parry said, he would not fail to inform Burghley.

And yet for all Parry’s spectacular wilfulness, he does seem to have begun fairly vigorously to gather news and information from Venice, a city which had for a long time been a European hub for intelligence from the Mediterranean and the Iberian peninsula. Much of it was gossip, though some of it was useful. In a letter to Burghley in late February 1583 Parry sent news from Flanders, Naples, Spain and Portugal. He wrote, too, of a new book that had been printed in Rome called De Persecutione Anglicana, known in an English edition as An epistle of the persecution of Catholickes in Englande. It was the work of Robert Persons, Edmund Campion’s fellow Jesuit in England, and had been first printed in Rouen in 1582.

Parry had never before shown very much interest in religion; he was drawn more to fine dinners in grand company. But here, for the first time, Parry hinted at his private view on what in Persons’s argument was the persecution of Catholics in England. Parry took the book very seriously. He told Burghley that it gave ‘a barbarous opinion of our [i.e. English] cruelty’, especially in the hanging, drawing and quartering of traitors: ‘I could wish that in those cases it might please Her Majesty to pardon the dismembering and quartering.’ Parry continued on this theme six days later when he wrote once again to Burghley: ‘I pray you tell Master Secretary [Sir Francis Walsingham] that here is so great speech of his persecution and cruelty that your lordship (sometime in the same predicament) is almost forgotten.’ Walsingham, the Earl of Huntingdon and the Earl of Leicester were ‘the men most wondered at’ in the great persecution. For a man who never wore faith on his sleeve, William Parry’s views on Robert Persons’s Persecution were surprisingly vigorous.

Any study of William Parry must point to his inflated self-regard, his snobbery, his peculiarly distorted sense of reality, his naive faith in Lord Burghley’s patronage and good fortune, his gambler’s instinct for taking wild chances, his stratagems and schemes. Parry was variable and vain, possessed of self-confidence over ability. In the spring of 1583 it would have been harder to find a more contrastingly different man to Parry than Thomas Phelippes, servant to Sir Francis Walsingham, who was engaged in secret work in France.

Phelippes was deliberate, able and self-reliant: a thoughtful, careful and compact man. He set out his letters with care; he wasted few words. He wrote in an italic hand, the mark of an educated man. His script was minute, perhaps showing something of the technical precision of a mathematician, which as one of the most gifted breakers of secret code and cipher in Europe Phelippes certainly was. Born in about 1556, he was the eldest son of William Phelippes, a London cloth merchant. He was a student, probably, of Trinity College in Cambridge. Beyond this, it is hard to be sure of the facts of Phelippes’s early life: he is one of the most secret and secretive characters in this book.

Phelippes was in France in July 1582, though it is not clear for what purpose. In Bourges he replied to a letter from Walsingham. His master had sent a letter in cipher for Phelippes to make sense of. For Walsingham this was a risk; the danger of having packets intercepted was real – indeed the letter Phelippes applied himself to was itself intercepted by Elizabeth’s government. It may have been one of William Allen’s letters, which were either stolen or bought from the European couriers fairly regularly in the early 1580s; or perhaps it was a packet sent to the Queen of Scots’s ambassador in Paris, the Archbishop of Glasgow. In 1580 the archbishop had complained to William Parry about a number of his letters that had been intercepted.

Whatever the letter was, to send it all the way to Phelippes in France was a measure of his unique skills in Elizabethan cryptanalysis. Phelippes told Walsingham that he had ‘travailed to the uttermost in the cipher’. He had had, he wrote, some success, ‘if not so good as was wished, sufficient yet I hope as to satisfy Her Majesty’. He gave a technician’s appreciation of the difficulty of the task, ‘won as it were out of the hard rock’. The problem was the writer’s terrible Latin: ‘whether it were of ignorance or policy the writer hath made so many faults as well in the Latin as the orthography that I was fain [compelled] to supply it almost everywhere by conjecture to make sense’.

Phelippes left Bourges in August and went on to Sancerre, between Nevers and Briare on the main post road out of Lyons. There he kept himself to himself: ‘I kept myself close in places of small bruits [rumours].’ He wanted to get to Paris, but his path was blocked by plague and sickness and the filthy winter weather of early 1583. He arrived in the city on or near to 13 March, for he was keen to report immediately to his master: ‘Being here now at the last arrived at Paris,’ he wrote to Walsingham, ‘the first thing I think it my part to do, is to remember my most humble duty unto your honour.’ In the letter he gave away little of his mission, though it seems to have been somewhere off the beaten track of Anglo-French diplomacy. In July Sir Henry Cobham, Elizabeth’s ambassador, knew that Phelippes was in Bourges and had sent his servant to visit him. Now in Paris Phelippes was sure that Walsingham would forgive the long delays of the journey. This was the confidence, not of a man like Parry, but of a trusted and discreet servant who could assure himself of Walsingham’s ‘gracious interpretation’ of his actions with few words of excuse.

The mystery of Thomas Phelippes’s mission remains its object and purpose. Phelippes had been in France for at least eight months. Perhaps he was gathering news from France or making contact with possible sources of information. Given that he spent some time hidden away on the main post road from Lyons to Paris, a route commonly used by priests travelling between the English College in Rome and William Allen’s seminary in Rheims, he may have been watching for émigrés or intercepting their letters. Whatever the nature of his mission, it did not involve a long stay in Paris. He had only just reached the city when he wrote his first letter to Walsingham, and already he was preparing to leave for England, giving ‘these few lines’ to let his master know of his return. He offered his ‘poor service’ to Walsingham at home or abroad.

While William Parry was in Venice vaunting his pre-eminent abilities to disrupt the queen’s enemies, the considerably more able Phelippes was engaged on a mission for Walsingham. He was a linguist and a mathematician, a talented young man in his late twenties. Above all, he was discreet and careful. In the coming years – from 1585 especially – Thomas Phelippes would prove himself to be Walsingham’s most secret and trusted servant, truly a man of the shadows.

William Parry, in contrast to Phelippes, enjoyed the light of attention and praise. He was a man who bored easily. He was worried that he heard very little from England, which meant that he was not sure ‘what to write or how to send’ it. To Burghley, Parry was a man of marginal significance, useful enough to cultivate but safe also to ignore. In Parry’s mind, however, he was his lordship’s faithful servant in Queen Elizabeth’s ‘special services’. He wrote: ‘I have presumed that your lordship hath ever esteemed me for a true man to my prince and country. So much whatsoever do come to your ears, I beseech you to promise for me and I will not fail to perform it God willing.’ To the world, William Parry was a poor and heavily indebted gentleman and a pardoned felon. In his own mind, he was a secret servant of great ability. This is why, in the early spring of 1583, he offered himself, without Burghley’s knowledge, as a double agent in Elizabeth’s service. He decided upon a great plan: to use the Pope’s ambassador to the government of Venice, the nuncio Cardinal Campeggio, to infiltrate the Church of Rome and prevent their conspiracies against Queen Elizabeth.

Parry first made contact with Cardinal Campeggio, to whom he was introduced by Jesuits in the city. Parry was certainly conferring with one Jesuit, Benedetto Palmio, with whom he discussed Robert Persons’s Persecution. Campeggio also received a good account of Parry from an English doctor living in Venice. He is likely to have been John Bradley, a man with a wife, children and property in the city whom Parry certainly knew.

Campeggio was Parry’s route to Rome, or so Parry hoped. The nuncio wrote to the Cardinal of Como, the cardinal secretary of state, in March 1583. Campeggio enclosed with his own a letter from Parry to the cardinal. It read:

I, William Parry, an English nobleman, after twelve years in the service of the Queen, was given a licence to travel abroad on secret and important business. Later, after pondering over the task committed to me and having conferred with some confidants of mine, men of judgment and education, I came to the conclusion that it was both dangerous to me and little to my honour. I have accordingly changed my mind and made a firm resolution to relinquish the project assigned to me and, with determined will, to employ all my strength and industry in the service of the Church and the Catholic faith.

Only Parry could have written with such style and abandon. He asked permission to come to Rome for a secret audience with the Pope.

Parry was overjoyed at the success of his secret approach to Campeggio and Como. He left Venice for Lyons, unable to stay in Italy, though whether on Burghley’s or Walsingham’s orders or because of money is unclear; Parry wrote of being ‘overruled by the necessity of my departure’. But nothing could tarnish his great secret coup. He wrote to Burghley, flourishing his talents, feeling victorious:

If I be not deceived I have shaken the foundation of the English seminary in Rheims and utterly overthrown the credit of the English pensioners in Rome. My instruments were such as pass for great, honourable and grave. The course was extraordinary and strange, reasonably well devised, soundly followed and substantially executed without the assistance of any one of the English nation.

Parry, the master spy, was preening himself. He wrote to Burghley that he would either discover and prevent all ‘Roman and Spanish practices’ against England or lose his life trying. This, he said, was a testimony of his loyalty to the queen and his duty to the honourable friends who had protected him. He wrote: ‘If it please your lordship to confer with Master Secretary touching my letters herewith sent, to advise and direct me, I am ready to do all I shall be able and am commanded.’

It seems very unlikely that either Walsingham or Burghley knew what Parry was up to in any precise way. In his letters he said nothing at all about his contacts with Campeggio, Como and Palmio. It could have been fatal for Parry to mention in his letters to London the approaches he had made to Rome. He never used code or cipher. As he wrote to Walsingham, ‘the miscarrying of my letters to you may cost me my life’. Parry – in seeking an audience with Pope Gregory XIII or indeed in working without the direct sanction of Burghley or Walsingham – was taking the greatest risk of his uncertain life.

Parry went from Venice to Lyons with the idea of building a network of agents. He was not shy in asking Walsingham for money. Whatever he spent, he said, he thought ‘well bestowed’. To recruit agents cost money: the cheapest of Parry’s contacts, so he claimed, was a secretary. Not surprisingly, Parry’s espionage, which reflected social rank and status, was expensive. One of his sources, a gentleman in Venice, came highly recommended: ‘This man (in my opinion) is well worthy Her Majesty’s entertainment in Venice where his credit and acquaintance amongst the nobility is very great. He is prepared already if it please your honour to use him.’ He came with Parry’s highest praise, ‘a very sufficient man to be entertained in Venice’, an ambassador to some of the greatest princes in Germany, and very honest.

In Lyons in the summer of 1583 Parry picked up the rumblings of a minor political scandal. Edward Unton, an English gentleman whose family connections extended to the Earl of Leicester and to Walsingham himself, had been imprisoned by the inquisition of Milan in late 1582 or early 1583. By June 1583 Unton was free and in Lyons, where Parry got to know him. ‘Master Unton speaketh very great honour of your lordship,’ he wrote to Burghley. He was, Parry wrote, a very proper and thankful gentleman, full of devotion to his prince and country: ‘I would to Christ England bred no other.’

Edward Unton’s companion in the inquisition’s prison had been an English Catholic called Salamon Aldred. This Aldred was once a tailor of Birchin Lane in London but by 1579 he was living in Rome. In fact, he was the same man who knew Charles Sledd, the spy whose evidence had helped to convict Edmund Campion and other priests in 1581, and helped to lodge Sledd in Rome. Aldred, like Sledd and now Parry, played a little at espionage. In 1582 he had offered to supply the Cardinal of Como with letters stolen from English diplomats abroad. Como had refused the advance. A few months later, one of Walsingham’s agents reported that ‘there is also at Lyons one Aldred, who hath a pension of ten crowns a month of the Pope, and he doth advertise Rome of all Englishmen that pass’. Aldred would soon come to the notice of Walsingham. In early 1583 he visited the English seminary in Rome. Parry and Aldred were by now men of the same world, of shady contacts, suspicion, and uncertain and divided loyalties. We have to wonder whether they fully understood the consequences of so tangled a life.

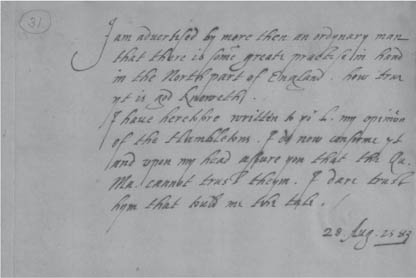

In the summer months of 1583 Parry was still alert to intelligence, though with what kind of critical filter it is hard to tell, especially given his continued contact with Campeggio. On 18 August he wrote: ‘I am advertised by more than an ordinary man that there is some great practice in hand in the north part of England. How true it is God knoweth.’ This was a short note to Burghley in Parry’s hand but without a signature. At the foot of the sheet of paper Parry wrote ‘Burn’. He rarely underplayed the dramatic aspects of his work. Still in Lyons, he reported on the movements of Salamon Aldred and Edward Unton. But by now he wanted to become a scholar as well as a spy. He suggested the idea was Walsingham’s: ‘The liberty that I have long desired to withdraw myself to some university is at last (by Master Secretary’s advice and favour) granted.’ He told Burghley that he would now spend the rest of his time abroad in Orleans and Paris, to return to England with ‘reasonable contentation’ – ‘if’, he added, reflecting upon his difficult times at home, ‘I be not to blame’.

A secret report by William Parry for Lord Burghley, 1583.

And so William Parry – spy, gentleman, debtor, convicted felon, prisoner, recruiter of agents and aspiring scholar – went off to Orleans. He hoped to spend the winter there, but was driven on to Paris by the threat of plague. In the city he had the good fortune to meet his old associate Master Stafford, now Sir Edward Stafford, the queen’s resident ambassador at the French court, and to make the acquaintance of Lord Burghley’s grandson, seventeen-year-old William Cecil, ‘whose good nature and towardness [aptitude or promise] beginneth to make a very good show already’. As ever he wished to show how grateful he was to Burghley: ‘I will do my best to make it appear how much I am bound to your lordship,’ he wrote. ‘And for my lord ambassador if anything come to my hands worthy his knowledge I have promised him the preferment.’

For all these flattering professions of service, it is clear that Parry’s contacts with Rome in autumn 1583 were just as strong as ever. Parry’s secret was that he had betrayed Burghley and Walsingham. Deluded by his own cleverness, he had proposed to the Catholic authorities a plan to betray Elizabeth’s government. Only the events of the coming months, when that plan matured into a plot to kill the queen, would show where his double loyalties really lay.