In 1583 the Duke of Guise, cousin to Mary Queen of Scots, gave money, time and men to a plan for the invasion of England. English historians have long known it as the Throckmorton Plot, thanks to the small but significant part played in its planning by Francis Throckmorton, a young English Catholic gentleman. The cast of principal English characters is a fairly narrow one: Throckmorton himself, who worked as a courier for the Spanish ambassador in London; Charles Paget, an English émigré and one of Guise’s men; his brother Thomas, Lord Paget, an English nobleman whose support for the invasion was sought by the duke; the Catholic earls of Northumberland and Arundel, both of whom had convenient strongholds near the coast where the invading army would land; and finally Lord Henry Howard, an elusive and subtle man, a Catholic and a supporter of the Queen of Scots.

The story begins in two very different places and with two quite different men: in the busy French port of Dieppe with a Sussex shipmaster, and then, some miles to the south-east, in Paris with the great Duke of Guise himself.

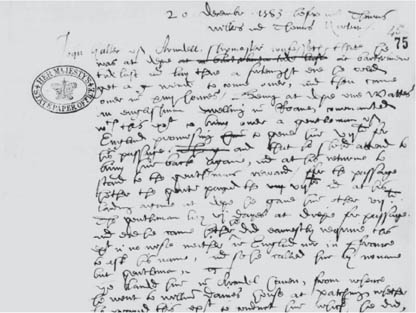

The man who called himself Wattes made his approach to John Halter in Dieppe on the feast day of Saint Bartholomew, 24 August, in 1583. Halter was the master and part owner of a bark, a small ship out of Arundel on the coast of Sussex. He was working for a London merchant, carrying a cargo of wooden boards to Dieppe, and in late August he was getting ready to return with nine fardels of cards and writing paper. Wattes told Halter that he lived in Rouen. He asked the shipmaster to take a gentleman over to England and then to bring him back to Dieppe. The price they agreed for this mysterious passenger was £7; once safely returned to France Halter would ‘stand to the gentleman’s reward’. A condition of the arrangement was absolute anonymity for the passenger, who, Halter later remembered, was earnest in requiring of him ‘in no wise neither in England nor in France to ask his name’. Halter knew him only as ‘the gentleman’. When he was later examined the shipmaster of Arundel gave no physical description of the man.

The shipmaster John Halter’s account of Charles Paget’s secret journey to England, December 1583.

In the first week of September a favourable wind blew, and John Halter’s bark set out from the harbour of Dieppe. The crossing to England took fourteen hours, and they went ashore at Arundel haven. The gentleman asked Halter to take him to the house of one William Davies at Patching, some four miles north-east of the haven, where they arrived at two o’clock in the morning of probably either Sunday, 8 September or Monday the 9th. Halter left the gentleman with Davies and returned to Patching about ten days later, where they had to wait three or four days for the wind and tide. When he was ready to sail, Halter spoke to Davies ‘to call the gentleman to come on board at the haven mouth’. On 25 September, the Wednesday before Michaelmas, Halter, the gentleman and his manservant, as well as a servant to William Shelley of Michelgrove and a man Halter did not know, went down to the haven. With only the gentleman and his servant as passengers, Halter’s bark landed at Dieppe on Friday, 27 September. It was a quiet crossing: the shipmaster and the gentleman did not speak on the return voyage because, as Halter later said, his passenger ‘was so sick at sea’. The gentleman stayed at Dieppe for a whole day, probably to recover from the rigours of his journey, before returning to Rouen.

John Halter was practised at smuggling people across the English Channel. Usually his passengers went only one way, from England to France, either to Le Havre or Dieppe. Many of those he took to France were members of the Earl of Northumberland’s household. They were Catholics or at least had Catholic connections. And they relied upon Halter’s discretion. The shipmaster did not ask questions: sometimes he knew who his passengers were, sometimes he did not. But they had to have lots of money, for bribing the English port officials was an expensive business. The going rate to pay off the searcher of Arundel, whose job it was to check ships and their passengers, was £40, though for this great sum of money the searcher had let ‘divers pass’. Or so said the writer of a secret report for William Allen in Rheims.

What was unusual, however, about John Halter’s gentleman passenger in September 1583 was a fact Halter may have suspected from the especially secretive means of their entry into England. The mysterious man who suffered so badly with sea sickness had come to Sussex to spy out the land for an invasion of Queen Elizabeth’s kingdoms by the Catholic powers of mainland Europe.

Behind it all was a meeting in Paris four months earlier, in June 1583, convened by Henry, Duke of Guise to discuss an invasion of the British Isles. Six men attended the meeting. They were Guise himself, one of the most powerful men in Europe and a passionate believer in the rescue of Elizabeth’s England from heresy; the duke’s spiritual confessor, Claude Matthieu; Archbishop James Beaton of Glasgow, the ambassador at the French court of the imprisoned Mary Queen of Scots; the Pope’s Nuncio in Paris, Castelli; William Allen, the guide and moral compass of English Catholics in exile; and François de Roncherolles, one of the duke’s men, who gave a military briefing.

Some, like Doctor Allen, favoured an assault upon England; others thought that any army should land in Scotland. By the end of June Guise had his plan. A force of 12,000 troops under the command of the Duke of Bavaria’s brother – most of them Spaniards, Germans and Italians – would sail from Spain to Flanders and land eventually in Lancashire, provoking a popular uprising of English Catholics in the north of England. Duke Henry would land with a second, smaller army on the Sussex coast, where he would use the local strongholds of the Earl of Northumberland at Petworth in Sussex and the Earl of Arundel at Arundel Castle. This was at last a serious effort to decapitate Elizabeth’s government once and for all: no wonder that in the spring and summer of 1583 the diplomatic connections between Spain, Rome and Paris buzzed with activity.

The Duke of Guise, cousin of Mary Queen of Scots, was thirty-three years old, tall and handsome, with a fair complexion and strawberry-blond hair. He was intelligent, athletic and charming, but also possessed the kind of arrogance and sense of high position that came of long nobility. In a country riven by religious civil war, the Guise family was immensely powerful, driven by a passionate hatred of Protestantism and the desire to revenge the murder of the second Duke of Guise by an assassin in 1563. They were not afraid to oppose even the French kings.

But the ambitions of Duke Henry went beyond the borders of France. Since the 1570s he had wanted to mount an invasion of England. His plans were often frustrated by a lack of either political and military will by King Philip of Spain or money, but Guise was always persistent in their pursuit. In 1578 he had consulted William Allen and representatives of Spain in the cause of his cousin Mary. The following year his chief agent travelled secretly throughout Europe. In December 1581 the duke had met Robert Persons, not long out of England, and William Crichton. Crichton, also a Jesuit priest, was an essential contact on Scotland, and a few months later, in spring 1582, he was involved in a project to restore Scotland to the Catholic faith through the agency of Esmé Stuart, Duke of Lennox, then in favour at the court of young King James VI. Lennox would command an army and restore the Catholic faith; Guise, Crichton and others discussed an invasion of 8,000 men planned for September 1582. But it all came to nothing because of the collapse of Lennox’s influence at James’s court, the cooling of King Philip’s support and the Pope’s unwillingness to provide money for the expedition.

But the Duke of Guise was not a man to give up easily. The meeting in Paris in June 1583 meant that a definitive battle plan was at last agreed, and in July Henry went to Normandy to begin to prepare for the invasion. He sent a gentleman of his household to negotiate secretly at Petworth with the Earl of Northumberland and, through intermediaries, with the Spanish ambassador at Elizabeth’s court, Don Bernardino de Mendoza. This gentleman’s name was Charles Paget.

Of all the English Catholic families caught between faith and loyalty, few were grander than the Pagets of Beaudesert in the county of Staffordshire. Of these Pagets none was subtler than Charles. He was a younger son of a noble family. His brother Thomas, a man in his middle thirties, was the third Baron Paget, inheriting the title in 1568 on the death of an elder brother, Henry. Their father, the first baron, was William Paget, one of the most powerful English politicians of the 1540s and 1550s, an adviser to monarchs, a diplomat and something of a king-maker. He died in 1563. His wife, Charles’s mother, the dowager Lady Paget, was a formidable woman who lived till 1587.

For some years before his secret visit to England Charles Paget tried to play a double game with Sir Francis Walsingham. The two men met in Paris in August 1581 when Secretary Walsingham was in the city on a special embassy. Paget’s problem was that he had crossed the English Channel without the queen’s licence. Paget had complained about his ‘lamentable estate’. He was sick and in need of physic. He felt he might be of use to Walsingham. He proposed to change his lodgings in Paris and to live a life of secrecy: in other words, he offered himself as a spy. But Paget had not counted on the reports of Elizabeth’s ambassador in Paris, Sir Henry Cobham, who made it plain to Walsingham that Paget was ‘a practiser against the estate’ and a known supporter of Mary Queen of Scots. Cobham had even refused to allow Paget into his presence. Paget appealed instead to Walsingham’s wisdom and humanity.

There is a clear record of what Sir Francis Walsingham thought of Charles Paget. It is a model of brilliantly compressed frankness, sharp as flint. He wrote:

I have of late gotten some knowledge of your cunning dealing and that you meant to have used me for a stalking horse. Master Paget, a plain course is the best course. I see it very hard for men of contrary disposition to be united in good will. You love the Pope and I hate not his person but his calling. Until this impediment be removed we two shall neither agree in religion towards God nor in true and sincere devotion towards our prince and sovereign. God open your eyes and send you truly to know him.

Of a busy and inveterate plotter Walsingham, like Sir Henry Cobham, had taken full measure. Charles Paget was an exile to watch very carefully indeed.

This was the man who in September 1583 set off for the Sussex coast from the port of Dieppe. Very few people knew his real name, including John Halter the shipmaster who landed him at Arundel haven, guided him to Patching in Sussex and brought him safely back to Dieppe. The alias Paget used, when he had to, was Mope. Perhaps his choice of name – as a noun it could mean a fool and simpleton, or as a verb to wander around aimlessly or be in a daze – was in ironic counterpoint to the precision of his secret journey.

As Dame Margery Throckmorton rode in her coach from London to Lewisham on the second Wednesday in October 1583 she reflected upon the best way to leave England secretly. She was thinking about this not for herself, but for the second of her four sons, Thomas. His younger brother George had tried it already and he had failed, stopped and searched at the port. Temporarily detained, his clothes and belongings had been taken from him. Lady Throckmorton wanted Thomas to be able to pass safely with money, plate, clothes and other things ‘to carry over with him for his own provision’. She wanted him to have the chance to live a new life abroad. She had heard that the safest way for Catholics to leave England was to go to the Countess of Arundel at Arundel Castle in Sussex, a few miles from where a gentleman with no name had come ashore from John Halter’s bark a month before. The countess could be approached through her physician, Doctor Fryer. Very probably this was Thomas Fryer, who lived near the church of St Botolph outside the city walls of London at Aldersgate. Dame Margery had already invited Doctor Fryer to dinner at her house in Lewisham the very next day.

When Dame Margery arrived at Lewisham she wrote a letter to her eldest son, Francis, at Throckmorton House in London. She wanted Francis and his brother Thomas to act quickly. She asked Francis to be at Lewisham early the following day to meet Doctor Fryer. She sent to both of her sons God’s blessing.

Francis Throckmorton received his mother’s letter. He replied immediately. He did not like the idea of getting Thomas abroad with the help of the Countess of Arundel. He asked his mother to persuade – even to command – Thomas not to cross the English Channel. Francis Throckmorton was a careful man in October 1583. As a courier working secretly and treasonably for the Catholic powers of Europe, he had every reason to be.

The Tudor Throckmortons were a great sprawling and long-established family of land and some influence. Francis Throckmorton’s father, Sir John, was the seventh of seven sons. One of his elder brothers, Francis’s uncle Sir Nicholas Throckmorton, had served as Elizabeth’s ambassador at the royal courts of Scotland and France. John Throckmorton himself was a lawyer and an important royal official. But in 1580 the family’s situation was not a cheerful one. Sir John was accused of slackness and corruption in office; he spent some time in the Fleet prison in London and was burdened by the enormous fine of 1,000 marks (nearly £700), which in his will he directed Francis, as one of his executors, to pay. He had over £1,000 of debts owing to him, but himself owed more than £4,000, to gentlemen, scriveners, tailors and a vintner; he had pawned his chain and other jewels. Sir John died in May 1580, two days after making his will. He left a widow as well as four sons (Francis, Thomas, George and Edward) and two daughters (Mary and Anne), of whom all but Francis were under the age of twenty-four. Burdened by debt and the reputation of corruption, he left behind him, too, a lingering sense of family disgrace.

There seems little doubt that the Throckmorton boys were brought up as Catholics. In 1576 Dame Margery was accused of hearing mass said by a seminary priest, and it was alleged that the same priest taught her sons. As young men the two elder brothers, Francis and Thomas, travelled abroad secretly and established connections in the Low Countries with Sir Francis Englefield, long known by Elizabeth’s government as a rebel and conspirator. By 1583 Francis Throckmorton was carrying letters between Mary Queen of Scots and the French ambassador in London, Michel de Castelnau, through Castelnau’s secretary, Claude de Courcelles. Throckmorton was a regular visitor to Castelnau’s residence at Salisbury Court, just off Fleet Street. Sir Francis Walsingham knew about this part of Francis Throckmorton’s life, for, though Throckmorton did not know it, Walsingham had Salisbury Court under close and effective surveillance.

Through the French embassy, Throckmorton became acquainted with three powerful men of the English Catholic nobility. The first was Henry Percy, eighth Earl of Northumberland, whose brother Thomas, the seventh earl, had been executed for treason in 1572. The second was Lord Henry Howard, the brother of Thomas, fourth Duke of Norfolk, beheaded as a traitor also in 1572. Lord Henry was forty-three years old, an exceptionally bright man and frequently suspected of murky political dealings with Catholics at home and abroad; these suspicions always seemed to lack firm evidence. It was once written of Lord Henry that ‘his spirit … is within no compass of quiet duty’. His subtle intelligence was peculiar among the Elizabethan nobility. The third of Francis Throckmorton’s acquaintances was the weary and melancholic Lord Paget, Thomas the third Baron, whose brother was the energetic Charles Paget alias Mope. Treason, it seemed, had a habit of running in some Elizabethan families.

To the casual observer – even in fact to the reader of intercepted private letters – Thomas, Lord Paget was a loyal subject of the Tudor crown. The behaviour and reputation of his exiled brother Charles appeared to cause him some pain. In late October 1583 Lord Paget wrote from London to Charles in Rouen. The letter was short and stiffly polite. Elizabeth’s government, he wrote, had not looked kindly upon Charles’s stay in Paris. His move to Rouen, where he was known to be mixing with other exiles and émigrés, was similarly ‘misliked’. Lord Paget advised Charles to travel further into France. He was troubled by reports – ‘advertisements’ – of what his brother was up to, writing: ‘in some advertisements lately come, [that] you are touched as not to carry yourself so dutifully as you ought to do’. If this news was true, Lord Paget was sorry. He warned his brother to be wary, and he made his own position very clear. The plainness of his words was almost for the official record: ‘if you forget what duty and loyalty you owe here, I will forget to be your brother’. He left Charles in God’s keeping.

Charles Paget never received Lord Paget’s stern brotherly warning: it was neatly filed away in the office of Sir Francis Walsingham and his staff. But more secret still was a fact masked by the crispness of Lord Paget’s message to Charles. The letter was a smokescreen; it may even have been a coded warning for Charles to keep himself safe. In fact, in late September the brothers had met to discuss the Duke of Guise’s plan to invade England.

Francis Throckmorton was arrested on the same day as Lord Henry Howard in the first week of November 1583. Throckmorton had been under surveillance for a long time, suspected ‘upon secret intelligence given to the Queen’s Majesty, that he was a privy [secret] conveyor and receiver of letters to and from the Scottish Queen’. By now the proof against him was fairly complete. But what may have prompted his arrest was the anxiety of Walsingham and other councillors over the strange treason of John Somerville, the Warwickshire gentleman who had set out from home to London with the intention of shooting the queen with his pistol. The government was very nervous.

On either 5 or 6 November, royal officials visited both Dame Margery Throckmorton’s house in Lewisham and Throckmorton House at Paul’s Wharf on the River Thames, a few streets south of St Paul’s Cathedral. Francis, it seems, was almost caught in the act of treason, ‘taken short at the time of his apprehension’ in composing a letter in cipher to Mary Queen of Scots. He was led away and his house was searched. Officers found in Throckmorton’s chamber two papers that listed the names of English Catholic noblemen and gentlemen and gave the descriptions of havens for the safe landing of foreign troops. Also found were twelve genealogical pedigrees of the ancestry of the English royal family supporting the claim of Mary Queen of Scots to Elizabeth’s throne.

The searchers at Throckmorton House missed, however, one vital piece of evidence. It was a casket covered with green velvet that, thanks to the quick thinking of Francis Throckmorton’s wife Anne, was spirited out of the house by their servants and taken to a friend of Throckmorton who lodged in Cheapside. The following day he handed it to one of the Spanish ambassador’s servants.

Francis Throckmorton had no time to make his dispositions. His wife and servants had to cope as well as they could. Throckmorton had visited Lord Paget the evening before his arrest. Recognizing the danger he was in, Paget, from his lodgings on Fleet Street, not very far away from Paul’s Wharf, began to prepare to leave England.

The day was Thursday, 7 November. Throckmorton House had been searched; so had the house of Dame Margery Throckmorton at Lewisham. Lord Paget wrote to a servant on his estates in Staffordshire: ‘for that I have occasion to use money … presently send me as much money as is any ways come to any of your hands to be here the 16 day of this month, for there I shall have occasion to use it’. He instructed his servants Twyneho and Walklate ‘and such other as you shall think meet come with all, but let them keep it very secret’. There was urgency here but no rush: Lord Paget believed he had just over a week to get his affairs in order. Clearly he was beginning to sense a very serious change in his fortunes, and this only a few weeks after his stern lecture to his brother Charles about loyalty.

As Francis Throckmorton was led away to custody and his house searched, two very experienced and rather tough privy councillors, Sir Ralph Sadler and Sir Walter Mildmay, interrogated Lord Henry Howard. Howard held out for as long as he could, asking to be allowed to speak to Sir Francis Walsingham personally. Both Sadler and Mildmay knew the importance of Lord Henry’s examination. Through Robert Beale, a clerk of the Privy Council, they asked to meet Walsingham on 10 November, after which they would brief the queen on their suspicions of Howard’s questionable activities.

Francis Throckmorton was taken first to the house of the master of the royal posts on St Peter’s Hill, one of the neighbouring streets to Paul’s Wharf. Throckmorton was kept there for two or three days before going to the Tower. He was allowed to meet ‘a solicitor of his law causes’, who brought to him papers and books. Throckmorton used the meeting to slip a note into one of them. Denied pen and ink, he wrote on one of his lawyer’s papers with a piece of coal the words ‘I would fain [gladly] know whether my casket be safe’. He took a fantastic risk. And so too did his lawyer, who after leaving Throckmorton went straight to Throckmorton House – down St Peter’s Hill, a right turn on to Thames Street, then the first left towards the river and Paul’s Wharf – and opened up his papers. He found the note, which he gave to one of Throckmorton’s household men.

On Friday, 15 November, William Herle, Lord Burghley’s long-serving intelligencer, his eyes and ears in London, wrote to his master. Herle was lodged at the Bull’s Head just outside the city walls at Temple Bar, close to Lord Paget’s house. On the very same day Paget, if his instructions were being followed, should have been expecting the arrival within hours of the servants and money he needed to leave England secretly.

Herle was interested in conspiracy. He knew of a great international plot that involved the Duke of Guise, the Throckmorton brothers and Lord Henry Howard:

The chief mark that is shot at, is Her Majesty’s person, whom God doth and will preserve, according to her confident trust in him. The Duke of Guise is the director of the action, and the Pope is to confer the kingdom by his gift, upon such a one as is to marry with the Scottish Queen.

Rumours in London said that the elusive Lord Henry was a priest, even (more fancifully but a mark of a surprising man) that he was secretly one of the Pope’s cardinals. And Herle knew all about Francis Throckmorton, for earlier that year he had told Secretary Walsingham of Throckmorton’s secret meetings with the French ambassador in London, ‘what long and private conferences, at seasons suspicious, and of his being at mass thereat several times’. Indeed one of Throckmorton’s kinsmen had dined with the French ambassador only that Sunday, 10 November (‘if I mistake not the day’). Francis Throckmorton, Herle wrote now to Burghley, was ‘a party very busy and an enemy to the present state’. Herle wrote again the next day to Burghley: ‘the world is full of mischief, for the enemy sleeps not’.

Under interrogation Francis Throckmorton’s story was that the incriminating papers found in his chamber at Paul’s Wharf were not really his. They had, he said, been the work of one ‘Rogers alias Nutteby’. To support this fabrication Throckmorton ‘found the means to get three cards’, on the back of which he wrote secretly to his younger brother George: ‘I have been examined by whom the two papers, containing the names of certain noblemen and gentlemen, and of havens, etc. were written.’ He had said that they were in the handwriting of a household servant, and hoped that George would confirm the fabrication. Unfortunately for Francis, however, the cards were intercepted. On 13 November Walsingham made an entry in his notebook of the order for George Throckmorton’s arrest.

Though Francis Throckmorton may have been offered a pardon for information on his serious crimes, at first he made a plain denial of any knowledge of treason. In the Tower of London, interviewed by privy councillors, he resisted examination. Thus refusing to talk, he was handed over to a number of commissioners with a warrant ‘to assay [attempt, try or test] by torture to draw from him the truth of the matters’. In the official account of his examination on the rack, the phrase used was ‘somewhat pinched, although not much’. The verb ‘pinch’ could mean a range of physical discomfort from irritation and annoyance to torture and torment.

Throckmorton was taken to the rack on 16 November. Still he refused to speak. He was given three days to recover physically, but quickly the decision was made to rack him again. On the 18th Walsingham sent the Council’s torture warrant to the Tower. Pragmatic and unflinching, Walsingham was blunt: ‘I suppose the grief [pain, torment] of the last torture will suffice without any extremity of racking to make him more conformable than he hath hitherto showed himself.’ To one of the interrogators he offered a grim reflection, writing that he had seen men as resolute as Throckmorton stoop – to submit or yield under coercion – ‘notwithstanding the great show that he hath made of a Roman resolution’.

Throckmorton spoke at last on 19 November. Walsingham, knowing the rack from experience, was correct: this time merely the threat of torture was enough to make him talk. He made a confession on 20 November, explaining how Sir Francis Englefield, in the government’s view one of the queen’s most dangerous enemies, had recruited him to carry letters to and from the Spanish ambassador in England. Throckmorton admitted that he had encouraged Englefield to press King Philip of Spain to invade England. He confessed, too, to having told his brother Thomas about the Duke of Guise’s earlier projected invasions of Scotland. When these plans had fallen through in 1582, Guise began once again to look to England:

if there could be a part found in England to join in the action and convenient places and means for landing, and other things necessary, there should be a supply for Guise of foreign strength. And [Throckmorton] said the Spanish ambassador in France called Juan Bautista de Tassis was acquainted with this matter.

On the day Francis Throckmorton was continuing to confess to his contacts with Sir Francis Englefield, William Herle, Lord Burghley’s intelligencer, wrote to his patron of his devotion to ‘public security’, while Thomas, third Baron Paget left London ostensibly for his estates in Staffordshire but actually heading for the coast of Sussex.

After leaving London on the 23rd, Lord Paget and his party of servants and gentlemen were on the coast of Sussex near Ferring on 25 November. On that Monday, ‘almost an hour within night’, a yeoman farmer was inspecting his land. He saw eight men on horseback riding on the highway towards the sea. One man rode ahead with his sword drawn. Six of the others followed, riding two-by-two. The eighth man came behind, though the farmer could not tell whether his sword was in or out of its scabbard. They were riding ‘for the most part all big horses or geldings’. He saw none of the men or their horses come back up the highway.

In this way, Thomas, Lord Paget left England secretly without the queen’s licence. It was a month to the day since he had warned his brother Charles in Rouen of the duty and loyalty he owed in England, threatening to forget him as a brother. With Paget was Charles Arundel, the son of a knight and through his mother a kinsman of the noble house of Howard – another Catholic gentleman, another exile.

Elizabeth’s advisers learned of Lord Paget’s flight less than a week after he and his men had ridden down to Ferring. They guessed that Paget and Arundel would make for Paris. On 1 December Walsingham wrote to Sir Edward Stafford with the queen’s order for her ambassador to keep a watchful eye on them. They had lately left England without leave; Stafford should seek very carefully to learn what they practised against the state.

In London there began a strenuous investigation of the facts. In the Tower Francis Throckmorton admitted that his ‘plat’ – his ‘platform’ or plan – of the harbours of Sussex was taken from maps. He had not scouted the coast for himself: that task was left to others. On 2 December he confessed to the involvement of Charles Paget in the Duke of Guise’s project to land fourteen or fifteen thousand troops in Sussex. Paget ‘was thereupon sent into Sussex in September 1583 to sound some noblemen and gentlemen there therein, and to view the havens’.

Although by the end of 1583 some pieces of the puzzle were still missing, it was clear that Walsingham and the Privy Council had discovered a major plot for an invasion of England. Elizabeth’s government knew from at least two sources – the interrogations of Francis Throckmorton and the information of Burghley’s intelligencer William Herle – that behind the plan was Henry, Duke of Guise. Both the French and Spanish ambassadors appeared to be involved. Lord Henry Howard was suspected of complicity, though the evidence against him was not yet conclusive. Lord Paget had left England without a licence in a great hurry. His brother Charles Paget was already deeply suspected of conspiracy. There was, in other words, a great tangle of suspicious activity: by Francis Throckmorton and his family and accomplices, by the Paget brothers and by Lord Henry Howard, on the streets of London and in the villages and hamlets of Sussex. In the weeks that followed, Walsingham and his men spared no effort to get to the root of one of the most pernicious conspiracies ever engineered against Queen Elizabeth and her government.