When it came to loyalty two factors – money and flattery – directed the flow of William Parry’s mercurial mind. Parry, the gentleman spy, was a snob; he enjoyed nothing more than a comfortable life mingling with important men. To Parry espionage was a means to secure for himself material comfort and influence, though he had few doubts that he was very good at it. Probably no other character in this book was as accomplished as he at self-deception. Taking an extraordinary risk, in 1583 he wrote to one of the Pope’s cardinals with an offer of service for the Catholic cause. Then, just as heroically, he reported to Lord Burghley and Sir Francis Walsingham his solo work as a master spy for queen and country.

In 1583 he had enjoyed himself in Venice, Lyons and Paris. By the time Parry returned to London in the summer of 1584, he was doctor of laws of the University of Paris. Whichever side he chose ultimately to serve – Rome or England – would rest on who gave him the patronage he felt he deserved and how effectively they tickled his vanity. Within months Parry’s life unravelled in an extraordinary way when, falling victim to his own deviousness, he sought and then failed to put into action a disastrous plan to kill Queen Elizabeth.

All through his career as a spy for Burghley and Walsingham, William Parry had consorted with Elizabeth’s enemies, seeking to reconcile them to the queen. The communications he had opened up with Rome in spring 1583, through the Pope’s nuncio in Venice, Campeggio, were on a very different scale; it was an elaborate and dangerous deception. This was probably why before his return to London he had told Sir Edward Stafford in Paris that he had intelligence for the queen’s ears only.

Parry was playing, in other words, a double game, but neither Lord Burghley nor Cardinal Campeggio knew whom he really served. Parry, in fact, was on no one’s side but his own. He played his double bluff so successfully that he found himself tangled up in a deception he could not control. On balance, however, he was probably Rome’s spy, for when he was in Paris in September 1582 he was secretly reconciled to the Catholic Church. More extraordinary still is that in 1583, influenced by the prospect of money and fame, he made a genuine offer to murder Queen Elizabeth. On this mission he blew hot and cold all the way through 1584. Probably if Lord Burghley had given Parry the patronage he wanted so desperately, then his bizarre story may not have ended on the gallows. Parry might then have preferred to forget his solemn promises to cardinals and priests. But this never happened. The cold welcome he found in London and the fear of financial ruin only fixed in his mind a desperate mission to assassinate the queen.

When Parry was reconciled to the Catholic Church in 1582, he was advised to live quietly in Paris. Few of the English émigrés in the city trusted him; they knew that he was in contact with Lord Burghley. From Paris, Parry went to Lyons and then Milan, where he satisfied the local inquisitor that he was a Catholic. He was in Venice by February 1583 at the latest. It was there that Parry (as he himself wrote) ‘conceived a possible mean to relieve the afflicted state of our Catholics, if the same might be well warranted in religion and conscience by the Pope’. At this time he read Robert Persons’s account of the vicious persecution of Catholics in England, which he discussed with a Jesuit priest, Benedetto Palmio. Palmio introduced Parry to Campeggio, the Pope’s nuncio to the Venetian government. Campeggio in turn wrote of Parry to the Cardinal of Como, the papal secretary of state.

Parry’s primary motivations were money and the desire to impress powerful men, though as a scholar he was interested too in ideas and arguments. He read dangerous books. To Burghley, in 1583, he mentioned Robert Persons’s polemic on the persecution of Catholics in England. A year later he read A True, Sincere, and Modest Defence of English Catholicques, William Allen’s answer to The execution of Justice, Lord Burghley’s account of the government’s lawful prosecution of Catholic priests as traitors. Allen’s Modest Defence was a particularly pernicious book to the Elizabethan authorities, strictly prohibited in England by royal proclamation. In just over two hundred pages, Allen condemned the persecution of English Catholics by Protestants under the pretence of treason charges, setting out also the authority of popes – indeed even of priests – to depose kings, calling them ‘judges and executors’ of the divine will. No prince, even a Catholic one, was beyond the Pope’s justice. Parry found in Allen’s powerfully persuasive book arguments that spoke directly to his conscience.

Parry wanted permission and papers to be able to travel from Venice to Rome, but for some weeks there was no clear idea of what kind of passport he should have. Nothing had been decided before Parry set off from Venice to Lyons. The fact that Parry had left for Lyons caused Campeggio to doubt whether Parry was sincere. Parry, however, was jubilant. It was only a fortnight later that he wrote the letter informing Burghley that he had shaken the foundation of the English seminary in Rheims and overthrown the credit of the Pope’s English pensioners in Rome.

It is likely that Parry’s high spirits came about from his meeting in Lyons with William Crichton, a Scottish Jesuit priest close to the Duke of Guise and involved in Guise’s various plans for the invasion of Scotland and England. With Crichton, Parry discussed the lawfulness of killing a tyrant. Crichton, said that such an assassination was not legitimate, citing Saint Paul in the New Testament (Romans 3:8): ‘Evil is not to be done that good may ensue.’ Parry disagreed: ‘it was not evil to take away so great an evil’. Yet in spite of their theological differences, Crichton became Parry’s new contact with the authorities in Rome. By late May Parry had received, thanks to Cardinal Campeggio, a safe-conduct to travel through the Papal States. It was no wonder that in the middle of June, still in Lyons, Parry wrote to Walsingham: ‘the miscarrying of my letters to you may cost me my life’.

Parry never went to Rome. He travelled instead from Lyons to Paris, where at some time between October and December 1583 he visited Thomas Morgan, Mary Stuart’s chief gatherer of secret intelligence. Their conversation changed Parry’s life and committed him to a desperate course of action. Morgan took him into a private chamber. Parry later described the meeting. Morgan, he said, ‘told me that it was hoped and looked for, that I should do some service for God and his Church. I answered him I would do it, if it were to kill the greatest subject in England: whom I named, and in truth then hated.’ ‘No, no,’ Morgan had said, ‘let him live to his greater fall and ruin of his house.’ Parry was talking about the assassination of his own patron, Lord Burghley. But, Parry claimed, Morgan in fact meant Queen Elizabeth. Parry’s reply was that so great a mission could be accomplished, if of course the theological case for the queen’s murder was clear: ‘it were soon done, if it might [be] lawfully done, and warranted in the opinion of some learned divines’. Parry’s theologian of choice was William Allen, whose Modest Defence had so influenced his thinking on the legitimacy of killing monarchs. But in fact it was a much humbler English priest, one Master Wattes, who, as William Crichton had done in Lyons, said plainly that it would be unlawful for Parry to assassinate the queen. Nevertheless Parry, persuaded by the arguments of Allen’s Modest Defence, told Morgan that he would kill Elizabeth – so long as the Pope allowed him to do so and in turn granted full remission of Parry’s sins.

Parry was able to convince Thomas Morgan and the Jesuits of his loyalty to their cause. He believed his reputation in Paris to be sound. But he still worried about secret enemies. For a night-time meeting with the Pope’s nuncio, Parry was heavily wrapped in a cloak for disguise. At the end of November Parry wrote to the Cardinal of Como: ‘There are never wanting jealous and spiteful people unacquainted with my actions who will seek to malign me and give information against me to His Holiness and your eminence.’ He asked Como to trust only the reports of the Archbishop of Glasgow and the Bishop of Ross (both ambassadors of the Queen of Scots), William Crichton, Charles Paget and Thomas Morgan. Parry sent another letter to the cardinal a few weeks later in which he enclosed an attestation by a Jesuit priest that in Paris he had confessed and received the sacrament of holy communion.

Parry left Paris in the last few days of December 1583, arriving in England at the port of Rye in January. Thanks probably to Sir Edward Stafford’s effusive praise (and probably also Burghley’s influence) Parry had ‘audience at large’ with Elizabeth. Playing the loyal subject and agent provocateur he ‘very privately discovered to Her Majesty’ the conspiracy he had engineered to kill her. In spite of his privileged access to Elizabeth, he was unable to convince her of the substance of the plot; she ‘took it doubtfully’. Parry was for the first time seriously worried that he had fatally incriminated himself. He left the queen’s presence in fear.

So now Parry faced the problem of loyalty. He had convinced Morgan in Paris of his seriousness in the mission of killing Elizabeth. The Cardinal of Como believed him to be a loyal Catholic, in spite of repeated warnings of Parry’s bad character. Could he be trusted? Charles Paget’s sister thought not: in January 1584 she wrote to her brother to say that Parry was a spy, and that everything Charles said to Morgan, Morgan repeated to Parry. ‘I pray you, good brother Charles, have great care with whom you converse.’ Her letter, intercepted by Elizabeth’s government, never reached him. Indeed Paget was certainly in contact with Parry. In February, from London, Parry thanked Paget for his ‘friendly letters’. So long as Paget promised to burn Parry’s letters, just as Parry destroyed Paget’s, he would continue to write. At the foot of this letter Parry wrote ‘Burn’. Paget, in Paris, never received it: the packet was intercepted by Elizabeth’s government.

Up to his neck in conspiracy, Parry was, as ever, troubled by money. He desperately needed Burghley’s patronage. Temporarily he appeared to turn away from treason, writing to Morgan in Paris to renounce his mission. He urged Morgan to burn their correspondence. Still hoping for better luck at court, in March he went to Greenwich Palace to petition Burghley for the vacant mastership of St Katharine’s hospital for poor sisters, near the Tower of London. But while at Greenwich Parry received a letter from the Cardinal of Como. The Pope, Como wrote to Parry, commended ‘the good disposition and resolution which you … hold towards the service and benefit [of the] public: wherein His Holiness doth exhort you to persevere’. Desperate about his future, this was just the warrant Parry had been looking for. Suddenly his doubts disappeared. He later confessed that he found in Como’s letter ‘the enterprise commended, and allowed’. Parry believed he was absolved in the Pope’s name of all his sins.

But Parry’s mind never rested in one place for very long. At times he was determined never to kill the queen. ‘I feared to be tempted,’ he later said, adding with a familiar dramatic touch: ‘and therefore always when I came near her, I left my dagger at home.’ He pondered Elizabeth’s excellent qualities. But then he asked himself: ‘Why should I care for her? What hath she done for me? Have I not spent ten thousand marks since I knew her service, and never had penny by her?’ True, she had given him his life when he had been pardoned of his conviction for the assault of Hugh Hare the moneylender. Still, he reflected, it would anyway have been tyranny to execute him.

In May, Parry was still hoping for Burghley’s help in the mastership of St Katharine’s, though Parry sent his great patron a letter the tone of which was peevish and resentful. He blamed his troubles on secret enemies. With no whisper of irony or self-doubt, he wrote of the strength of his loyalty in matters of religion and duty: quite a feat of psychological gymnastics for a man who in Paris had sworn to murder the queen. Parry was sure that Walsingham and Burghley could help him easily to secure the mastership of St Katharine’s. He thought no other candidate was better suited: ‘I would to Christ Her Majesty would command any further trial of me.’ ‘Remember me, my dearest lord,’ he wrote, ‘and think it not enough for a man of my fortune past to live by meat and drink. Justice itself willeth it should be credit and reward.’ Yet Parry’s letter came to nothing, and his hopes were frustrated. At the foot of his letter to Burghley he wrote the word ‘Burn’. As usual, Burghley ignored him.

Two months later, in July, Parry read the signals correctly: he despaired of any success in promotion and preferment. He left Elizabeth’s court, he later wrote, ‘utterly rejected, discontented, and as Her Majesty might perceive by my passionate letters, careless of myself’. He went back to London from Greenwich Palace to find that a copy of William Allen’s Modest Defence had been sent to him from France. Did Thomas Morgan send it or Charles Paget? Whoever gave Parry a copy of the Modest Defence knew his man, for once again the despondent spy and commissioned assassin felt the persuasive power of Doctor Allen’s arguments. The Modest Defence, Parry said, ‘redoubled my former conceits: every word in it was a warrant to a prepared mind: it taught that kings may be excommunicated, deprived, and violently handled: it proveth that all wars civil or foreign undertaken for religion, is [sic] honourable.’

By August 1584 Parry had regained some of his equanimity, though he was having to fight hard to convince Burghley of his loyalty. Burghley wondered instead whether Parry was quite the gentleman he claimed. Someone had cast doubt upon Parry’s gentility, and Parry wanted to reassure Burghley, who was an obsessive genealogist with a keen nose for the lineage of gentlemen and noblemen, of his good name and reputation. From his lodgings in Fetter Lane near Holborn, Parry set out to defend himself.

Parry’s short autobiography may suggest some of the reasons for his tangled and complicated life. He explained that his family had been long established in the county of Flintshire in north Wales. But where he had blood and ancestry, he lacked money. Parry set out his circumstances; their theme was a genteel and unfortunate poverty. He wrote that his father was a poor gentleman who had served in the king’s guard. Parry was one of sixteen children by his mother (his father’s second wife) and he had fourteen half brothers and sisters. His father had died early in Elizabeth’s reign at the improbably fantastic age of 118 years, a father to thirty children with very little land of his own. Clearly William Parry had to compete against extraordinary domestic odds: probably the eager, often combative tone of his letters even to powerful men is not very surprising.

Parry had married twice for money, though not with great success. His second wife’s income was £80 a year, four times his own. Unable to spend her money, he had to scratch a living from his own. He professed prudent domestic economy. Dice, cards, hawking and hunting, he said, had never cost him more than £20. He supported two of his nephews in their studies at Oxford and maintained four others, one of whom was in France, another in London, and two at a country school in Flintshire. For ten years he had helped a poor brother and his wife and their fifth son. He gave money weekly to twelve poor folks in the village in which he had been born. He also wrote pointedly of the cost of his ‘trouble and travail’, by which he meant his work abroad for the queen. So he admitted to his generosity and to his poor management of money. He said nothing of his enormous debts or of his conviction for the assault of Hugh Hare the moneylender three years earlier. He threw himself upon Burghley’s mercy. His own life, and the lives of those of his family whom he supported, rested on Burghley. With unhappy urgency he wrote: ‘All this (my best lord) is as true as the Lord liveth. Help therefore I beseech you, or else you shall shortly see me and all these to fall at once. For truly they shall not lack while I have.’ Burghley, predictably, was unmoved.

Though by late summer desperate for promotion and patronage and burdened by the strain of the mission he had undertaken on behalf of the Cardinal of Como, Parry was not a man to give up easily. For a long time he had believed that his interests lay with the powerful Cecil family. In Paris he had got to know Robert Cecil, Lord Burghley’s son, and Burghley’s grandson William Cecil. In August Robert, still in Paris, wrote to Parry with genuine affection. Parry grabbed his chance a month later, when Robert Cecil’s cousin, Sir Edward Hoby, appointed Parry his solicitor at court. Hoby was twenty-four years old, schooled at Eton and Trinity College, Oxford – the very same young man Parry had tried to entangle in his dubious money-making scheme back in 1581, which had led to Parry’s imprisonment in the Poultry Counter. Either Parry had not properly learned his lesson or, desperate for his chance to succeed, he carried on regardless. Parry now wrote of his work for Sir Edward with confident self-assurance: ‘I am fully acquainted with his state and daily occupied in settling such matters for him as may most import him in profit and credit.’ He felt ‘most bound’ to do all he could for Sir Edward. Young Hoby at least was convinced: he wrote to his uncle Burghley to extend to Master Doctor Parry the same credit he would give to his nephew. Parry was as ever the persistent petitioner. As he wrote to Burghley: ‘if it please you to commend me as a fit man for a deanery, provostship or mastership of requests it is all I crave’.

Yet in spite of his remarkable (even delusional) persistence the months of 1584 were miserable ones for William Parry. Returned at long last from his foreign travels and travails, he was settled in London. ‘I never liked country better, nor of all persons of quality received better usage,’ Robert Cecil wrote to Parry from Paris. Doctor Parry’s feelings in London were quite the opposite. He felt his was a cold homecoming. In May he perceived the sharp stab of failure; he was desperate for preferment; he was growing resentful that his great talents were being passed over; he discerned the slanders of secret enemies. Though he succeeded in earning the trust of an upcoming and talented young gentleman of good connection like Sir Edward Hoby, Parry believed that the sacrifices made in the service of the queen had brought him no reward. He was able to make powerful friends, yet the great prizes of patronage continued to elude him. To Burghley and Walsingham he professed loyalty and service to Elizabeth. The truth, however, is that after August 1584 Parry was working out the most effective way to assassinate the queen.

Parry recruited a fellow conspirator. His name was Edmund Nevylle, a gentleman of good connections in the north who shared a surname with the earls of Westmorland. Parry claimed Nevylle as his cousin, though he later said that Nevylle was a sponger who often came to his house on Fetter Lane to ‘put his finger in my dish, his hand in my purse’. In the end Nevylle betrayed him. Parry noted sourly: ‘the night wherein he accused me, [he] was wrapped in my gown’.

The facts of what happened between August 1584 and January 1585, the critical months of the conspiracy, have to be teased out of a thicket of self-justifying obfuscations in the later statements of Parry and Nevylle. Their conspiracy began with a discussion of William Allen’s Modest Defence. Certainly they took some time to arrive at a firm plan. First Parry visited Nevylle at the Whitefriars, and Nevylle returned the courtesy one morning to find Parry lying in bed in his lodgings on Fetter Lane. At dinner they spoke about Parry’s disappointment over St Katharine’s hospital. His only way of redress, Parry said, was to kill the queen. According to Allen’s Modest Defence, which had captured Parry’s imagination in a powerful and dangerous way, Parry believed that such an act was lawful. Nevylle, it seems, preferred to free the Queen of Scots from her English captivity. But in the end he came round to Parry’s proposal for assassinating Elizabeth, and the next morning Nevylle came again to Parry’s lodging. He swore on the Bible ‘to conceal and constantly to pursue the enterprise for the advancement of [the Catholic] religion’.

Eight days later Parry and Nevylle walked together in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Parry proposed a plan for them to execute. They would kill Elizabeth in Westminster near St James’s Palace, recruiting eight or ten household servants on horseback, all armed with pistols, to surprise her coach from both sides. Nevylle found ‘an excellent pistollier’, a tall and resolute gentleman whom he introduced to Parry at young Sir Edward Hoby’s house on Cannon Row, in the shadow of Westminster Palace. Parry, careful to keep the conspiracy between himself and Nevylle for the time being, declined the help of this sinister marksman.

At some point Parry and Nevylle discussed a much more fantastic plan. Doubtless influenced by the experience of his private audiences with the queen, Parry suggested the murder of Elizabeth in her private garden at Whitehall Palace. Helped by Nevylle, he would escape over the palace wall to one of the landing stairs near by, taking a boat on the River Thames. Both proposals were fraught with dangers, but only the assault on Elizabeth’s coach near St James’s was even remotely plausible. Still, even this ambitious scheme required the kind of premeditation and intricate planning for which William Parry and Edmund Nevylle were constitutionally unsuited.

The two conspirators did nothing. Doctor Parry’s feelings of injustice and resentment continued to simmer away in his mind. From late November 1584 he sat in the House of Commons for the tiny borough of Queenborough in Kent, thanks very probably to his young patron Sir Edward Hoby. It was Parry’s first time in parliament, and he certainly left his mark.

In December the Commons debated a bill for the queen’s safety. It was the bill that became the Act for the Queen’s Surety, the extraordinary statute that gave the force of law to the killing by private subjects of anyone who challenged either Elizabeth’s life, throne or kingdom. It was a measure aimed squarely at the pernicious influence of Mary Queen of Scots and her supporters. Not surprisingly, though with a marked lack of judgement, Parry spoke angrily against the bill. On 17 December he said in open debate that it ‘carried nothing with it but blood, danger, terror, despair, [and] confiscation’. Shocked at this violent outburst, the officials of the Commons hauled Parry out of the chamber. He was called before Elizabeth’s Privy Council and disciplined by the speaker of the Commons. Next day Parry went down on his knees to say to the house that had spoken rashly and intemperately; he apologized. Disciplined and chastened, Doctor Parry was readmitted to his seat in parliament. But he still intended to kill the queen.

The House of Commons was in recess from late December till the first week of February 1585. In this break from parliamentary business came the deciding moment of William Parry’s treachery. Parry, who had volunteered in Rome to play the assassin and who could never resist a dramatic performance, began to live his role. But his cousin Edmund Nevylle was beginning to have doubts.

On Saturday, 6 February, at between five and six o’clock in the evening, Parry visited Nevylle at the Whitefriars. The time to make their final plan had come at last. He wanted to talk to his cousin alone, and so, presumably because they were in company, they withdrew to a window. Nevylle told Parry about his reservations. He would not go through with the conspiracy. It was the moment of crisis. Parry wanted Nevylle to leave England straight away, promising him a safe passage to Wales and so on to Brittany. Nevylle refused, saying that in conscience he had decided to ‘lay open this his most traitorous and abhominable intention against Her Majesty’. At this last meeting between the hesitant conspirators, when their plot finally fell to pieces, it seems Edmund Nevylle paid the final insult to Doctor Parry by being wrapped in his cousin’s gown. And so Nevylle surrendered himself to the authorities. He made his confession on Tuesday, 9 February, spoke again on the 11th, and was questioned for a third time a day later. Apprehended, William Parry made his own ‘voluntary confession’ on the 13th, at last telling the story of his reconciliation to the Church of Rome and his negotiations with the Cardinal of Como.

Parry the doctor of laws knew that two accuser-witnesses would be required to convict him of a treasonable act: it was Nevylle’s word against his. This was probably Parry’s reason for not taking Nevylle’s gentleman marksman into his confidence at their meeting on Cannon Row. But it helps to explain why between them Parry and Nevylle, though convinced of the justice of murdering Elizabeth, had never quite come up with a feasible plan. As soon as Nevylle voiced his doubts, Parry had no choice but to abandon the mission.

In the end William Parry was undone by his own cleverness, self-possession, greed and arrogance. Probably he would have settled for Burghley’s patronage if it had been offered in 1584. Instead the bitterness of service left unrewarded corroded any loyalty he had to Burghley, Walsingham or the queen. Burghley in particular had thrown Parry’s service back in his face, or so Parry must have thought; the obsequious letters to the great man, all that energy expended on acting the eager gentleman, the lord treasurer’s slights and the silences – we can well imagine these provoked in a character as fractured as Parry’s murderous ill-feeling. So the seeds of treason had long been sown. Playing the great assassin in Paris, encouraged by men as influential as Thomas Morgan, Charles Paget and the Cardinal of Como, was in the end irresistible to Parry. Those seeds were nourished by long months of frustration in England. Parry’s plan was desperate, unfeasible, even a fantasy. But it was, in his own mind at least, real enough.

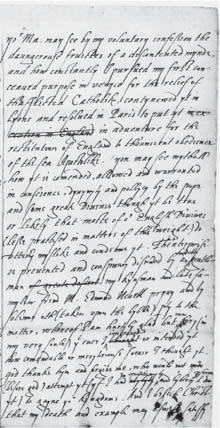

William Parry’s letter to the queen, 14 February 1585: ‘you may see … the dangerous fruits of a discontented mind’.

On Saint Valentine’s Day in 1585, Sunday, 14 February, Doctor Parry wrote to Queen Elizabeth from the Tower of London: ‘Your Majesty may see by my voluntary confession the dangerous fruits of a discontented mind, and how constantly I pursued my first conceived purpose in Venice for the relief of the afflicted Catholics, continued it in Lyons and resolved in Paris to put it in adventure for the restitution of England to the ancient obedience of the see Apostolic.’ To the Earl of Leicester and to Lord Burghley, once his employer, he emphasized just how special he was: ‘My case is rare and strange, and, for anything I can remember, singular: a natural subject solemnly to vow the death of his natural Queen … for the relief of the afflicted Catholics, and restitution of religion.’

A week later he was tried for treason in Westminster Hall. The clerk of the crown set out the facts and stated that Parry had been seduced from his true allegiance by the Devil. Yet Parry did his best to control even his own trial; he refuted as well as confessed, saying that he wanted to die; he was determined to explain his thinking, volunteering to read to the court his own confession and letters. Words he had written to Burghley and Leicester became part of the public record: ‘My cause is rare, singular and unnatural.’

For William Parry the desire to play a great part both in secret and in public was a powerful and compelling one. His treason was, of course, sensational news. Even the trial of John Somerville in 1583, after which Somerville hanged himself in Newgate prison, had nothing like the performance of a star like Parry: with Parry being as self-possessed and fluent as ever, the crown’s lawyers had found it difficult to keep him quiet. Lord Burghley was troubled about eager London printers getting their presses ready to tell Parry’s story. They, like Parry himself, had to be controlled. Some of the most powerful men in England, councillors and law officers, met at Burghley’s house on the Strand to discuss how best to publish what they called ‘the truth’ of Parry’s treason. In other words, they decided what could and could not be told. The official account, produced by the queen’s printer, was truly savage. Carefully edited copies of documents were used to prove Parry’s vile treasons. The pamphlet demolished his character (especially his ‘proud and arrogant humour’) and the insulting pretensions at good family and gentility of such a ‘vile and traitorous wretch’. Burghley hated a traitor, more so one who was also a social upstart.

This unrelenting public denunciation of the man was a mark of the depth and horror of Doctor Parry’s betrayal. Public prayers celebrated the deliverance of Elizabeth from Parry’s wicked plot. What gave his treason a special edge were the debates in parliament on the bill for the queen’s safety. After the murder of the Prince of Orange in 1584, the Elizabethan political establishment had been terrified of the queen’s assassination. Parry made that fear real and tangible. Nowhere in the propaganda was it admitted that he had spied for queen and country: the public story was that he had been simply an assassin hired by the Pope’s cardinals to kill Elizabeth. Parry’s long if erratic service to Lord Burghley, his secret intelligence from Paris, Lyons and Venice, his closeness to members of the powerful Cecil family: all these strands of his varied career were lost to official amnesia.

Parry was executed in Westminster Palace yard on 2 March, the only serving member of the English House of Commons ever to have been arrested for high treason. On the scaffold he maintained his innocence, denying any plan or even any thought to have murdered the queen:

I die a true servant to Queen Elizabeth; from any evil thought that ever I had to harm her, it never came into my mind; she knoweth it and her conscience can tell her so … I die guiltless and free in mind from ever thinking hurt to Her Majesty.

Perhaps he really believed that this lie was in fact the truth. If so, then William Parry had yet another reason to feel that his service to Elizabeth and Burghley, for so long unrewarded, had once again been abused. He died a traitor’s death, hanged till he was almost dead, disembowelled, beheaded and dismembered, his head and limbs put on display throughout London to warn others of the cost of treason.