In fact Thomas Phelippes had no need for Sir Francis Walsingham’s geldings. Phelippes’s heroic ride to Lichfield never happened, more is the pity. Anthony Babington had not ridden out to Staffordshire. He was in London, safely under observation, if not yet under arrest. Some time at night on Tuesday, 2 August an informant told Phelippes that if he went to Robert Poley’s lodgings he could take Babington and a whole knot of his friends. Phelippes went there, finding no one. Perhaps, he thought, the informant had mistaken Babington for someone else. ‘I marvel,’ Phelippes wrote to Walsingham, ‘what mystery there is in this matter.’

As Phelippes had suspected, Anthony Babington was troubled by Walsingham’s postponement of their meeting, but Poley was able to convince him that if he went to Walsingham to make a ‘discovery’ of the conspiracy he could save his life and secure his freedom. Poley even hinted at a royal audience for Babington, and the naive young man, excited by the thought, saw to his wardrobe, getting ready his best clothes. He said he now knew everything about the plot. He showed Poley his deciphered copy of the ‘bloody letter’, the text Babington and his friend Tycheborne had laboured at together. He gave no hint to Poley that he would send a reply to Mary. Instead he wanted to tell the whole story of the plot to Walsingham. Babington had no idea that he had moved one step nearer to the hangman’s rope.

A little before eight o’clock on Wednesday morning, 3 August, a messenger came from Phelippes to tell Mylles that Babington was still in the city but had taken new lodgings outside London’s walls in Bishopsgate Without, on the road to the village of Shoreditch.

Information could travel only as quickly as a messenger on foot in London or a courier galloping out from the city to the court at Richmond Palace. So it was that on Wednesday morning Walsingham, at Richmond, was the last to know that Babington had not slipped the net. He was sure that Babington had panicked and run, and hoped that Poley, whom he was expecting for a meeting early that morning, would be able to offer some explanation of what was going on. Walsingham was disappointed at how events had turned out. What nagged him was the thought that the forged postscript Phelippes had added to Mary’s letter had ‘bred the jealousy [suspicion, mistrust]’ in Babington. Still, John Ballard was quite as important as Babington.

Within hours the situation had changed. Phelippes alerted Walsingham to the facts as quickly as he could. Babington was in London; it seemed he had changed his lodgings. Now Walsingham considered a question he had not had the luxury to be able to ask a few hours earlier. Was it better to have Babington in custody or to wait a little longer in the hope of intercepting his promised reply to the ‘bloody letter’? Walsingham wrote to Phelippes: ‘it is a hard matter to resolve. Only this I conclude: it were better to lack the answer than to lack the man.’

By now Walsingham and Phelippes were playing an extraordinarily delicate game. Relieved that Babington was in the city and determined to have him under lock and key, Walsingham needed Robert Poley to keep Babington calm. At their meeting at Richmond that Wednesday morning, Sir Francis told Poley that once again he would have to postpone his interview. The queen had been sick in the night, he said, and the Privy Council was busy with Irish affairs; he could not leave court. Walsingham now proposed to meet Babington at Barn Elms in three days’ time. In the meantime, Sir Francis wanted Babington, through Poley, to make a plain report of the conspiracy. Once again it was a ruse: the purpose of the postponement was to give Phelippes plenty of time to make Babington’s arrest.

Poley, showing a surprising loyalty to Babington, spoke persuasively to Walsingham on the young conspirator’s behalf. He assured Sir Francis of Babington’s devotion to ‘the public service’. Poley told Walsingham what Babington had told him. A man called Ballard, ‘a great practiser in this realm with the Catholics’, was plotting to stir a rebellion, ‘set on’ by the ambassador of Spain and Charles Paget. This was hardly startling news to Walsingham, but, playing along, he asked Poley to thank Babington for the information.

But could he rely upon Poley? Sir Francis reflected that his agent had not dealt with him dishonestly, yet he was loath (as he wrote to Phelippes) ‘to lay myself any way open unto him’. Robert Poley was not a man to be entirely trusted. At Richmond Walsingham had told Poley only as much as was necessary to provoke what was needed from Babington. Poley’s task was to keep Babington occupied with the prospect of Walsingham’s favour while Mylles and Phelippes organized his arrest. Indeed Walsingham ordered that Babington’s apprehension should be delayed no longer than Friday, 5 August. Francis Mylles was ready with a new arrest warrant signed by Lord Howard of Effingham. Mylles and Phelippes were determined to cover up any trace of the part Secretary Walsingham had played in breaking up such a terrible conspiracy against the queen.

Poley returned from Richmond Palace to his lodgings, where he found Babington and gave him Walsingham’s message about the second postponement of their meeting. Babington was worried, but Poley was able once again to reassure him of Sir Francis’s friendship and favour.

The gloom of early Wednesday morning, 3 August, quickly lifted. If Walsingham and his men could not secure Anthony Babington’s answer to the Queen of Scots’s letter they would at least get Babington. He was under surveillance: with Babington in his new lodgings in Bishopsgate Without, in the north-east corner of London, he was watched by Walsingham’s agent Nicholas Berden, who lodged nearby in the precincts of Bethlehem hospital.

Berden followed Babington and his friends, hoping to see John Ballard. Babington and some of his co-conspirators met at the Royal Exchange at about seven o’clock in the evening, where for half an hour or so they ‘had some earnest discourse’. After talking, they went to the Castle tavern (their usual haunt) for supper. After supper Berden followed each gentleman to his lodging, hoping but failing to see Ballard. It was midnight when he went off duty.

Within hours, however, John Ballard, priest and conspirator, was a prisoner. The day was Thursday, 4 August. At Poley’s lodgings in the morning Babington had spoken to John Savage. Between eleven o’clock and twelve noon Poley’s chambers were raided by a party consisting of a city official and two royal pursuivants, bearing a warrant for Ballard’s arrest signed by Lord Admiral Howard. Neither Francis Mylles nor Thomas Phelippes was anywhere to be seen. Ballard was promptly escorted under guard to the Counter prison in Wood Street. It was not a surprising thing to happen to one of the many Catholic priests in the lodging houses and taverns of London. There was not a hint that he was a principal conspirator in a plot to murder Elizabeth. In fact the city official was the father of Phelippes’s servant Thomas Cassie, and the pursuivants had been stationed with Francis Mylles for days. The raiding party was made up by Nicholas Berden’s brother-in-law. Mylles’s and Phelippes’s intricate plan had worked perfectly.

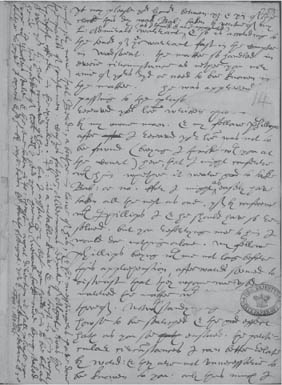

Francis Mylles reports the capture of John Ballard, 4 August 1586.

Or had it? After a textbook raid, Mylles was as troubled as ever. First of all, he did not trust Walsingham’s contact with Babington, Robert Poley. After searching Poley’s chambers Mylles had little hesitation in writing to Walsingham that Robert Poley was ‘a notable knave’ and could not be trusted. Mylles suspected that Poley was playing both sides for his own advantage.

Much more worrying was the effect of the raid upon Anthony Babington’s nerves. Probably it was pure chance that he was there, and even if the raiding party knew who he was they could hardly do much about him: the whole purpose of the exercise was to arrest Ballard as yet another Catholic priest living secretly and illegally in England. But on 4 August Babington broke: disconcerted by the delays in meeting Walsingham, he was unnerved by Ballard’s arrest. He wrote a final and remarkable letter to Robert Poley: ‘Robin … I am ready to endure whatsoever shall be inflicted … What my course hath been towards Master Secretary you can witness; what my love towards you yourself can best tell. Proceedings at my lodging have been very strange. I am the same I always pretended. I pray God you be and ever so remain towards me.’ He said that the furnace was prepared to try their faith. He ended as ‘Thine how far thou knowest’. And then Anthony Babington ran for his life.

Thursday, 4 August became in official circles the formal date of the discovery of the conspiracy of John Ballard and Anthony Babington, the ‘principal managers and contrivers’ of this latest plot against Elizabeth’s life, and their seventeen ‘actors and assistants’. The object of the conspiracy of Babington and Ballard was to execute three treasons. Firstly, the destruction of the queen’s person. Secondly, the encouragement of a foreign invasion and a domestic rebellion of Catholics and malcontents. Thirdly, the liberation of the Queen of Scots and the advancement of her claim to Elizabeth’s throne. But on 4 August only John Ballard was in custody: Anthony Babington and many of his friends were free men.

On Friday, 5 August Walsingham made a report to the queen. Till this point he had kept her well briefed on the twists and turns of the plot. She trusted his discretion in keeping everything he knew of the conspiracy to himself: in Walsingham’s words, ‘both the depth and the manner of the discovery of this great and weighty cause’. Elizabeth clearly understood the implications of the Babington Plot, aware like her advisers of the Act for the Queen’s Surety. She did not want to have set in motion the special commission to try the Queen of Scots. She did not want the blood of an anointed monarch, even one deposed and as dangerous as Mary, on her hands.

By now John Ballard was under heavy guard in the Counter prison. If he refused to speak, Walsingham thought that the best course of action was to take him to the Tower of London to be tortured for information. But Anthony Babington and all the other members of his group of conspirators had flown, so provoking the most urgent man-hunt of the whole of Elizabeth’s reign. One eyewitness, a Jesuit priest living and working secretly in London, saw it at first hand: ‘all ways were watched, infinite houses searched, hues and cries raised, frights bruited in the people’s ears, and all men’s eyes filled with a smoke, as though the whole realm had been on fire’.

The authorities were furiously busy. Lord Burghley wrote a royal proclamation that called upon all subjects to search out and apprehend Babington and Chidiocke Tycheborne. Watchmen patrolled villages and towns near London. Witnesses to the activities of Babington and his companions, including their families and household servants, were closely interrogated. Pursuivants and constables searched houses throughout London. Thomas Phelippes worked tirelessly on the questions that would be put to Babington and the other conspirators when at last they were captured.

John Savage the would-be assassin was one of the first to be taken. He was interrogated by Walsingham and the queen’s trusted vice-chamberlain, Sir Christopher Hatton. Of Savage’s second examination, on 11 August, Phelippes made the following significant note:

Omitted by Savage in his confession in writing of that he delivered by speech to Master Vice-chamberlain and Secretary Walsingham.

That the Queen of Scots was made acquainted with the designs as well of invasion as attempt against Her Majesty’s person by the letters of Babington and that there came an answer from her touching her assent and advice but what it was the contents particularly he knew not.

That one of the guard about the said Queen of Scots being a brewer was corrupted and won to serve the Queen of Scots’s turn for conveyance of letters.

That by means of Gilbert Gifford they had intelligence with the French ambassador.

It was clear as day that Babington, Savage and the others had been deceived completely. Savage confirmed that in the ‘bloody letter’ Mary had assented to the plot to murder Elizabeth. Savage believed, wrongly, that the brewer of Burton upon Trent worked for the Queen of Scots, whereas in fact he was paid by Sir Amias Paulet and Thomas Phelippes to do exactly what they told him to do. And finally Savage thought that Gilbert Gifford was a trusted courier who carried letters between Mary and ambassador Châteauneuf in London. Here was the early confirmation, if Walsingham and Phelippes needed it, of the staggering success of their secret operation against the Queen of Scots.

It was only a matter of time before all the members of Babington’s group were rounded up. A few of them managed to get well away from London: two were caught as far as Cheshire, one in Worcestershire. Most, however, made it only a little way out of London before being captured. From Westminster, Babington and two of his companions ran to St John’s Wood, north of London. Joined by some of the others, they hid in deep countryside for ten days before going on to Harrow, where, by now desperately hungry, they begged for food. They were arrested on 14 August and taken to the Tower of London the following day.

Babington in particular was interrogated with an almost obsessional intensity. We know of nine separate examinations, each one accompanied by a written statement, conducted by privy councillors and the crown’s law officers between 18 August and 8 September. On 1 September Babington was presented with the cipher he had used in his correspondence with the Queen of Scots, meticulously set out by Phelippes; after all, Phelippes knew the cipher better than Babington did himself. In the presence of a notary public, Babington affirmed that it was the alphabet ‘by which only I have written unto the Queen of Scots or received letters from her’.

Mary Queen of Scots’s cipher is attested to by Anthony Babington before the Privy Council, 1 September 1586. [National Archives, Kew, SP 12/193/54]

Just as significantly, given Savage’s confession on 11 August, Babington recalled from memory the contents of the last letter he had received from the Queen of Scots. She ended, he wrote, ‘requiring to know the names of [the] six gentlemen: that she might give her advice thereupon’. He was referring to the forged postscript added to the original letter by Phelippes. Babington had not the faintest idea of Phelippes’s sleight of hand.

One young man who could have given critical help in these long summer days of interrogation was Gilbert Gifford, Walsingham’s prize double agent in penetrating the conspiracies of the Queen of Scots. Walsingham, more anxious about Babington and Ballard, had noticed his disappearance on 3 August. Gifford, seeing that the group of conspirators was about to be broken up, panicked. Terrified of being implicated with John Ballard and then swept up in the arrests of Babington and the others, he left England secretly. More at home in France, Gifford went to the city he knew best in Europe, Paris.

In the middle of August Gifford revealed himself to Walsingham and Phelippes. He was very nervous: he knew full well that he had left England without the queen’s licence; he was now just another émigré. Choosing his words carefully, he wrote to ask Walsingham to forgive his sudden departure and offered his continued service. To Phelippes, with whom he had worked so closely for months, he excused his flight abroad, wrote of his willingness to serve Walsingham ‘as long as there is blood in my body’, and asked for £10.

Walsingham and Phelippes were always quick to see an opportunity. Gifford could spy once again in Paris. After all in England he had been a devastatingly effective agent and he knew the émigré scene in Paris as well as anyone. Keen to be of use to Elizabeth’s government (especially after his unlicensed journey to France) he made an offer of espionage that Walsingham accepted. Within weeks Gifford wrote with joy and relief at Sir Francis’s favour and protection ‘in doing that dutiful service towards my dear country whereunto by all laws I am bounden’.

So by September Gifford was spying once more, picking up packets of foreign correspondence for Phelippes. He had left his cipher for Phelippes’s letters in England and was signing reports with own name. He was offered a new means of secret communication. Anything of importance was to be written by Phelippes in alum: often called alum-water, this substance was normally used in medicines and to dye cloth and leather, but here Gifford suggested its use as a secret ink. Gifford asked too for money, which Phelippes was able to get to him by means of bills of exchange through Gifford’s uncle, a merchant who traded out of Rouen. He was sent Phelippes’s equipment ‘for the manner of secret writing’ with Phelippes’s instructions on how to use it.

It was obvious that Gifford’s cover story in Paris would have to be maintained. The blunt fact, of course, was that Elizabeth’s government had to denounce Gifford as a conspirator and a traitor. As Walsingham wrote to Phelippes: ‘He must be content that we both write and speak bitterly against him.’ This kind of cover was necessary, but it came with a cost.

Sure by September of Walsingham’s confidence, Gifford was at last completely honest in saying why he had bolted so unexpectedly in August. He called Babington, Ballard and the other conspirators ‘ambitious treacherous youthful companions’. He was terrified of being exposed to their treasons. But his greatest fear was to be called as a witness in their public trials, which, when he left England, he could clearly see were imminent. Standing before a packed courtroom, he would have to acknowledge that he had not only spied on the Babington group but had also betrayed the Queen of Scots. It was a profound risk he was not willing to take. For Gifford, the familiar émigré haunts of Paris were safer than the courts of royal justice in Westminster Palace. His father had little sympathy. Hearing reports and rumours of the confessions of the Babington plotters, John Gifford understood the dangerous tangle in which Gilbert found himself. He wrote to Phelippes: ‘Sir, I have written to my unfortunate son. I would God he had never been born.’

Sir Francis Walsingham, Thomas Phelippes, Gilbert Gifford, Thomas Barnes, Robert Poley, Anthony Babington, Chidiocke Tycheborne, John Savage, Sir Amias Paulet, the honest brewer of Burton upon Trent: each of these in his own way, some playing greater parts than others, had set in motion judicial proceedings against Mary Queen of Scots. That was clear as early as August 1586. By the first week of September Walsingham and Lord Burghley were directing a very serious effort to gather definitive evidence of Mary Stuart’s complicity in the plot to kill Elizabeth and invade her kingdoms. Their chief expert researcher, naturally, was Phelippes.

Phelippes’s analysis of the evidence shows how tantalizingly close he and his masters had come to proving Mary’s guilt. Phelippes reviewed her correspondence with Charles Paget, her ambassador in Paris the Archbishop of Glasgow, the Spanish ambassador Don Bernardino de Mendoza, Lord Paget and Sir Francis Englefield. He assembled for Burghley what he called the ‘Proofs of a plot’. But the Queen of Scots had been careful. There was nothing in her own handwriting, only in the hands of her secretaries Gilbert Curll and Claude Nau. There was at best a glimmer of a chance of tying Mary definitively to her last critical letter to Babington.

The evidence of Nau and Curll was critical. Had the Queen of Scots composed the ‘bloody letter’? Arrested and put under enormous pressure in long interrogations, Nau confessed to a preparatory ‘minute’, or rough draft, of it. The very same day, recognizing at once its significance, Walsingham wrote to Phelippes: ‘I would to God those minutes were found.’ But Nau had made too convenient a confession. The next day Walsingham realized from yet another interview with Nau that ‘the minute of her answer is not extant’.

Phelippes saw and understood the problem. He knew that Mary had always been at least one step removed from the letters her secretaries sent out in her name. As a practised cryptographer, he reflected that she dispatched ‘more packets ordinarily every fortnight than it was possible for one body well exercised therein to put in cipher and decipher’. She was ill and of course she was a queen who had secretaries to write for her. So not surprisingly Phelippes’s view was that the ‘heads’ (that is, the points to be included) of what he called ‘that bloody letter’ sent to Babington ‘touching the designment of the Queen’s person [i.e. the murder of Elizabeth], is of Nau his hand likewise’.

For three days, between 5 and 7 September, Phelippes found himself pulled in two directions. On the 5th, Gilbert Curll, under detention and pressed by Elizabeth’s most senior privy councillors, confessed that he had deciphered Babington’s letter to the Queen of Scots and that her answer had been first written in French by Nau and then translated into English and finally put into cipher by Curll himself. On the same day, suggesting something entirely different, Nau told four senior privy councillors that Mary had written the ‘bloody letter’ to Babington in her own hand. Both Nau and Curll cautiously acknowledged the accuracy of the government’s copies of the letter, knowing they really had little choice but to do so. They were not, so far as we can tell, ever shown the forged postscript. But this was still not quite enough for Burghley and Walsingham, which explains why on 7 September Phelippes found himself to be the recipient of a peremptory letter from the court at Windsor Castle: ‘Her Majesty’s pleasure is you should presently repair hither, for that upon Nau’s confession it should appear we have not performed the search sufficiently. For he doth assure we shall find amongst the minutes … the copies of the letters wanting both in French and English.’

But like the search for the philosopher’s stone, neither Phelippes nor any other official could find that final and fatal proof against Mary Queen of Scots in her own hand. Elizabeth’s government would have to rely on the weight of the many documents to or from Mary or in her name that Phelippes had deciphered and gathered. Against so formidable and dangerous an enemy as the Scottish Queen, they pressed on regardless.

Anthony Babington and his fellow conspirators were tried in two groups between 13 and 15 September. The case of John Savage, accused of planning from the beginning the queen’s assassination, was the first to be heard. Brought to the bar, the charge was put to him: that in April 1586 at the church of St Giles-in-the-Fields he had conspired to murder Elizabeth, to disinherit her of her kingdom, to stir up sedition in the realm and to subvert the true Christian religion. Soon after this he devised with John Ballard how to bring this about, encouraged by letters he had received from Thomas Morgan and Gilbert Gifford. (It was no wonder that Gifford had fled England at the first sign of a trial.) Savage was asked to plead guilty or not guilty to the charge. He equivocated, only to be then sharply corrected by Sir Christopher Hatton:

SAVAGE : For conspiring at St Giles’s I am guilty; that I received letters whereby they did provoke me to kill Her Majesty I am guilty; that I did assent to kill Her Majesty I am not guilty.

HATTON : To say that thou art guilty to that and not to this is no plea, for thou must either confess it generally or deny it generally, wherefore delay not the time, but say either guilty or no. If thou say guilty then shalt thou hear further; if not guilty, Her Majesty’s learned counsel is ready to give evidence against thee.

SAVAGE : Then, sir, I am guilty.

The law officers set out the evidence against him, much of it from his own confessions. The attorney-general felt they had done quite enough to prove the case. But Hatton once again interjected with an important question for the defendant:

I must ask thee one question. Was not all this willingly and voluntarily confessed by thyself without menacing, without torture, or without offer of any torture?

Savage simply said ‘yes’.

Hatton asked for an adjournment of the trial to the following day, pointing out that if the court were then to hear the evidence against all the prisoners it would be in session till three o’clock in the morning. Over the following two days Babington and his fellow conspirators were tried for treason. They pleaded guilty to conspiring to free the Queen of Scots from confinement and attempting to alter England’s religion, but not guilty to planning Elizabeth’s murder. Yet the evidence was overwhelming, and the jury found them guilty on all charges. In court Babington blamed Ballard for his destruction.

Elizabeth took a special interest in how they were to be executed. On the day before Savage’s trial, she told Lord Burghley that ‘considering this manner of horrible treason’ against her own person, the form of the conspirators’ executions should ‘for more terror’ be referred to herself and her Council. Burghley replied that the usual way of proceeding, by ‘protracting’ the pain of the traitors in the sight of the London crowd, ‘would be as terrible as any other device could be’. Burghley was talking about hanging, drawing and quartering, a savage and brutal death. Still, Elizabeth wanted the judge and her privy councillors to understand her royal pleasure. She wanted vengeance, for the traitors’ bodies to be torn into pieces.

And so it was that Anthony Babington and his companions were executed on gallows specially constructed near the church of St Giles-in-the-Fields, where Savage had first concocted his murder plot, on 20 and 21 September. The deaths of Ballard, Babington, Savage and Chidiocke Tycheborne were quite as terrible as Queen Elizabeth, demanding the full execution of royal justice, wanted them to be.

Where the queen insisted on savage deaths for the conspirators, she dithered on Mary Stuart. By now there was no way to avoid the examination of the evidence against the Queen of Scots by the commission of privy councillors and lords of parliament. The fearsome mechanism of the Act for the Queen’s Surety had been set in motion. The Queen of Scots would answer for her conspiracies against her royal cousin. In weeks of nervous preparation, councillors and lawyers directed by Lord Burghley felt their way cautiously through the evidence. There was no precedent for what they proposed to do, trying a foreign monarch, even one deposed, by English laws for treason to Elizabeth. Acutely conscious of proper form, they were not even sure what to call Mary in the proceedings of the commission. With the imagination of Elizabethan lawyers, they settled on ‘the Scottish Queen’.

The commission met at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire between 12 and 15 October 1586. In the great hall Mary was brought before ten earls, one viscount and twelve barons, who sat on long benches on either side of the chamber. The queen’s privy councillors occupied chairs of their own. At a table in the centre of the hall were the crown’s law officers and two public notaries. The proceedings were conducted under the great cloth of state, Elizabeth’s coat of arms, the mark of royal justice.

It was a contest between old enemies. Mary, forty-three years old and too long in confinement, had been worn down and prematurely aged by prison. Both Lord Burghley and Sir Francis Walsingham had been ill, yet ferociously busy in preparing for the commission. Still, the wits of Mary, Burghley and Walsingham were as sharp as ever.

The Scottish Queen wanted nothing to do with what she thought was a travesty of a hearing. She was, after all, a monarch and accountable only to God. Human justice could not touch her – or so she maintained. She contested the commission’s jurisdiction over her as a foreign prince and she mocked the evidence it brought against her. She was not allowed lawyers; nor, significantly, was she permitted to examine the documents used by the crown’s law officers and by Lord Burghley (who sat as a kind of presiding officer for the commission) to prove her guilt; this was common practice in treason trials, though in Mary’s case it had special significance. The evidence, so carefully and diligently prepared by Thomas Phelippes, was read out loud in the great hall of Fotheringhay.

The commission was confident in the strength of an overwhelming case against the Scottish Queen. It was not, however, sure enough of the weight of Phelippes’s forged postscript of Mary’s ‘bloody letter’ to Babington. The evidence is complicated and open to a number of readings, but it seems likely that when Babington’s first confession was read to the commission his reference to Mary’s request to know the identities of his six fellow conspirators was left out. Likewise, the text of the ‘bloody letter’ put to Mary’s secretaries Nau and Curll and read out at Fotheringhay did not have the postcript appended.

Why was this the case, when Walsingham and Phelippes had taken so profound a risk to forge the postscript in the first place? First, it was because the documentary evidence produced by the commission against Mary was cumulatively strong enough to prove the crown’s argument. Mary had corresponded with Elizabeth’s enemies; she knew well enough of their plots and conspiracies. Secondly, the weight placed by the commission on the testimonies of Nau and Curll meant that the text of the ‘bloody letter’ had to be consistent with what they had seen, and they had not (so far as we can tell) seen the postscript. Thirdly, the commission was nervous of anything that could jeopardize the precision of their case. By October, with the political context now wholly altered, the view of Burghley and Walsingham must have been that the postscript added nothing materially to the evidence presented at Fotheringhay; it would be too much of a risk to use it.

Not allowed to examine the documents for herself, Mary’s defence followed predictable lines. She pounced on the weakness of the commission’s case. She was sharp, though at times she broke off to weep. She said she did not know Babington, had never seen him or received any letter from him. It was a poor argument, she maintained, to say that because Babington had written to her she had been a party to his conspiracy. True, she desired news and intelligence from her friends. True also, that people sent her letters, though she did not know who they were or where the letters came from. Babington’s confession was read out once again. She denied that she had written any such letter to him. And then she asked the question Burghley and other members of the commission must have been expecting. She asked to see her own handwriting. With the patience of an executioner before his victim, Burghley countered by showing to the commission – but probably not to Mary – copies of Babington’s letters.

The Scottish Queen knew from the documentary evidence being used in the prosecution that her secret correspondence had been penetrated. Somehow Lord Burghley had copies of letters that had passed secretly between Anthony Babington, Claude Nau and Gilbert Curll, and her friends and allies in Europe. She suspected underhand practice. Above all, she suspected Sir Francis Walsingham, who, as one of the observers of the commission, was sitting close by in the great hall of Fotheringhay. The Scottish Queen demanded of Walsingham whether he was an honest man. He stood up from his place at the opposite end of the chamber to Mary, walked to the lawyers’ and notaries’ table in the centre of the hall and spoke:

Madam, I stand charged by you to have practised something against you. I call God and all the world to witness I have not done anything as a private man unworthy of an honest man; nor as a public man unworthy of my calling. I protest before God that as a man careful of my mistress’s safety I have been curious [anxious, concerned, solicitous].

At this reply – a masterpiece of subtle wordplay that said everything and nothing at the same time – Mary’s response was to weep. She protested that she would not make a shipwreck of her soul in conspiring against her good sister Elizabeth. But she also spoke with venom against Walsingham. Those he had set for spies over her, she said, also spied for her against him. It seems unlikely that he was disconcerted by her claim. He knew both his men and his methods. And he, quite unlike the Scottish Queen, was not on trial for his life.

Soon after this the Scottish Queen made the dramatic gesture of withdrawing herself from the great hall. She wanted nothing more to do with the commission’s proceedings; she had heard enough. It made little difference. In Mary’s absence the commissioners continued to hear the evidence against her. Elizabeth effectively hamstrung the proceedings by ordering Lord Burghley not to allow the commission to give a sentence on Mary’s guilt. But, though at first depressed by an inconclusive end to the hearing at Fotheringhay, the commissioners were not prepared to let slip their best opportunity so far to destroy the pernicious influence of the Scottish Queen.

After an adjournment of ten days, the commission met once again, in the Star Chamber in Westminster Palace. This time Mary was not present to misdirect or mislead the commissioners in their reading of the evidence against her. Her secretaries, Nau and Curll, once again swore to the accuracy of the documents they had seen, all carefully prepared and set in order by Thomas Phelippes. Even more than this, Curll said that when he had deciphered Anthony Babington’s letters and then read them to his mistress he had ‘admonished her of the danger of those actions, and persuaded her not to deal therein, nor to make any answer thereto’. She had of course ignored him. Curll’s sworn testimony made Mary’s guilt plainer than ever.

At last the commission passed sentence upon the Queen of Scots:

By their joint assent and consent, they do pronounce and deliver their sentence and judgement … divers matters have been compassed and imagined within the realm of England, by Anthony Babington and others … with the privity, of the said Mary, pretending title to the crown of this realm of England, tending to the hurt, death and destruction of the royal person of our said lady the Queen.

After this it was a long and complicated road to Mary’s execution, one along which Queen Elizabeth was pushed and prodded very unwillingly by her senior advisers. Elizabeth wanted Mary to be quietly killed at Fotheringhay. She made it plain to Sir Amias Paulet, Mary’s keeper, that he had subscribed to the Association for the revenge of any treason against queen and country. Why, Elizabeth asked, could he not pursue her to death as he had sworn to do? Shocked at the suggestion, Paulet refused to stain his conscience.

What Elizabeth resisted for as long as she could was the act of signing her royal cousin’s death warrant: she did not want the blood of her royal kinswoman on her hands. When Elizabeth at last signed the document, in February 1587, the Privy Council dispatched it to Fotheringhay so quickly and secretly that Elizabeth had no time to change her mind to any effect. The Scottish Queen was dead long before Lord Burghley happened to tell Elizabeth that the warrant had been sent off to Fotheringhay. In a furious temper, the queen blamed everyone except herself. Her junior secretary, William Davison, who had taken the signed warrant to an inner caucus of privy councillors, went before Star Chamber and then went to prison. He was lucky: Elizabeth had wanted Davison to be hanged. Lord Burghley, for the first time in his long career, was dismissed from Her Majesty’s presence. It was one of the most decisive and extraordinary moments in English history. Thanks to the clandestine and ruthless work of Walsingham and Phelippes, and the resolution of Walsingham’s colleagues in the Privy Council and in parliament, the politics of Elizabeth’s reign were never quite the same again.

Did the end justify the means? Were queen and country served by the employment of methods that by modern standards of justice are questionable, to say the least? Certainly a forgery, the tangle of the Babington Plot and a show trial at Fotheringhay and in Star Chamber meant that Mary Queen of Scots could be eliminated once and for all. Elizabeth Tudor was at last free of her rival. But in 1587 even the cleverest of the queen’s advisers could not properly apprehend what they had done. Mary’s death did not take the sting out of a contested Tudor succession. War with Spain and the Pope was now certain. But there were other intangibles, the principal of them being one that would rumble on through the centuries. In defence of queen and country, Elizabeth and her ministers had killed a monarch.