The queen’s pursuivants pulled Thomas Barnes out of bed late at night on Thursday, 12 March 1590. They found him in his lodgings at the Saracen’s Head on Carter Lane, close to St Paul’s Cathedral. They suspected that he was a Catholic priest. He was in fact one of Sir Francis Walsingham’s most prolific spies.

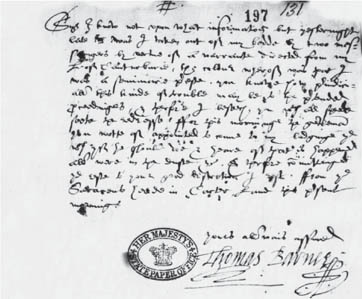

Barnes was still at the Saracen’s Head the next morning; it seems that somehow he was able to talk his way out of arrest. Having no idea of who had denounced him, he took up his pen and a sheet of folio paper to compose a letter to Thomas Phelippes. He wrote quickly and heavily, correcting his mistakes as he went along, blotting some words; he was not bothered by elegant penmanship. In fact Barnes was seriously annoyed: ‘You know how prejudicial this kind of trouble may be to the pretended proceedings and therefore I beseech you with all speed seek the redress.’ He was meant soon to meet his émigré contact, but if that gentleman found out about the pursuivants’ raid, he told Phelippes, ‘alls were in dust’. Barnes signed the letter with his full name, sealed it and addressed it to his very good friend Master Thomas Phelippes.

Barnes was by now an agent of two years’ experience. Walsingham and Phelippes had formally recruited him in 1588. Before that, from the spring of 1586, he had unknowingly worked for Phelippes, carrying letters secretly to and from the Queen of Scots. He was Gilbert Gifford’s cousin and Gifford’s substitute courier, though he knew nothing about Phelippes’s operation. So when in 1588 Walsingham and Phelippes presented to Barnes the facts of what he had done for the Scottish Queen, he found himself wrongfooted and vulnerable to a charge of dangerous espionage. His future was in the hands of Walsingham and Phelippes. They came to an agreement Barnes felt it prudent not to refuse. To Walsingham he offered his service to God and queen ‘by discovering or bringing to light any of the treacherous intents towards the state’ of fugitives and traitors at home and abroad.

Thomas Barnes writes to Thomas Phelippes from the Saracen’s Head on Carter Lane, March 1590.

And that is exactly what he went on to do. When Thomas Barnes wrote without ceremony to Thomas Phelippes from the Saracen’s Head he was working as Phelippes’s agent. His task was to discover the Catholic émigrés’ plans and conspiracies. His contact on the continent was Charles Paget, that most dangerous of exiles, who sent Barnes letters and questions about conditions in England. Phelippes was by now an artist of double-cross, drafting reports that Barnes communicated back to Paget in his own hand using the cipher they, Paget and Barnes, had agreed between themselves. When he was not in London, Barnes’s familiar territory was Antwerp and Brussels, from where he wrote to Phelippes in cipher. To cover any association with Phelippes, Barnes addressed his packets to John Wytsande, a London merchant. A man of order and habit, Phelippes had a mark to preserve the secrecy and anonymity of Barnes’s reports. It was the Greek letter alpha with a dot placed carefully over the top.

All of this was difficult and delicate work to which Phelippes brought care, patience and his customary eye for detail. The stakes were high. In these years of heavy and expensive European war it was clear that for Spain the defeat of the Great Armada of 1588 was a temporary failure. Open warfare between the Tudor and Habsburg monarchies was a fact. The seriousness of Barnes’s espionage can be measured by the fact that one of his contacts abroad was Hugh Owen, the chief émigré intelligencer to the Duke of Parma. Paget and Owen and their paymasters wanted to make sense of England’s capacity to withstand the military power of Spanish forces and to prepare for another armada. Phelippes sought to play Paget and Owen at their own game, trying with Barnes’s help to discover what the émigrés knew and, important also, to plant false information. Always the subtle master of deliberate calculations, Phelippes misled and disinformed Elizabeth’s enemies.

Phelippes understood the human factor of his secret work. He had to keep Barnes on the straight and narrow path, all the time watching Paget and Owen, through their letters to Barnes, for any suggestion of suspicion or double-dealing. As Phelippes wrote some years later: ‘the principal point in matter of intelligence, is to procure confidence with those parties that one will work upon, or for those parties a man would work by.’ In other words, it was an exercise in skilled manipulation. And in the case of Phelippes and Barnes the collaboration lasted for years longer than probably either man ever expected. Over a decade later, in January 1602, Phelippes’s younger brother Stephen happened to come across both men hard at work writing a secret paper.

Three weeks after the pursuivants had found Barnes at his lodgings in the Saracen’s Head, Sir Francis Walsingham died at his house on Seething Lane near the Tower of London. His health had been poor for many years, and he had taken frequent long leaves of absence throughout the 1570s. He suffered with a urinary complaint; he may have had a kidney stone. One of his spies, Robert Poley, suggested it was a venereal disease. In an unguarded remark Poley said of his employer: ‘Marry, he hath his old disease the which is the pox in his yard [penis] the which he got of a lady in France.’ It was a scurrilous and unwise thing to say about a man as powerful as the queen’s secretary.

Walsingham’s health began to fail for the last time in 1589. His work as secretary was overwhelming and he was pushed to the limits of his physical ability. His office was punishing enough for a healthy man. He failed to attend meetings of the Privy Council between February and June 1589. Though rallying a little at the end of that year, he made his last will and testament on 12 December.

He died an hour before midnight on Monday, 6 April 1590. On the following day Walsingham’s office staff retrieved their master’s will from a secret cabinet. A few hours later, at ten o’clock that Tuesday night, he was buried in St Paul’s Cathedral. Walsingham wrote in his will that he wanted his body to be buried ‘without any such extraordinary ceremonies as usually appertain to a man serving in my place’. This says something of his austerity: Walsingham was a powerful man, but he had never played the flamboyant courtier; he was ever the queen’s loyal servant.

His will was short and compact, a sparse record of a man’s life and loyalties. In it Sir Francis was concerned only with his wife and daughter. Of the bequests to charity or gifts to household servants common in the last testaments of his colleagues there was nothing, other than £10 of plate left to each of the three overseers of the will. Thomas Phelippes was nowhere mentioned.

Walsingham was disciplined, controlled and vigilant, ever watchful for the queen’s security. Lord Burghley wrote of his death as ‘a great loss, both for the public use of his good and painful long services, and for the private comfort I had by his mutual friendship’. He continued in the heavy language of divine providence:

we now that are left in this vale of earthly troubles, are to employ ourselves to remedy the loss of him hath brought, rather than for grief of the lack of him that is dead, to neglect of actions meet for us, whom God permitteth still to live.

Life and politics – and espionage – carried on without Walsingham, though in a quickly changing world.

He had always possessed a passionate sense of mission. He apprehended a war between God’s people and the forces of the Devil. Walsingham had seen with his own eyes the massacre in Paris at Bartholomewtide in 1572. It was clear to him that Elizabeth’s Protestant England fought for its survival against enemies at home and abroad. There was no distinction in Sir Francis’s mind between the political efforts of the Queen of Scots, the Duke of Guise, the Pope and the King of Spain and the work of their agents, Charles Paget, Francis Throckmorton, Anthony Babington and many others. Catholic priests and Jesuits were traitors, for in their eyes Queen Elizabeth was a heretic and a bastard. When William Allen and other priests spoke of their pastoral mission to save England from heresy and schism, Elizabeth’s advisers knew that they sought to do so by force and treason. This would have been as obvious to Walsingham as it was to Burghley when both men read Allen’s violent denunciation of Elizabeth’s tyranny weeks before the Great Armada set sail in 1588. Walsingham’s sharp eyes would not have missed Allen’s allegation of the ‘Machiavellian’ and godless methods used by Elizabeth’s government:

she hath by the execrable practices of some of her chief ministers, as by their own hands, letters, and instructions, and by the parties’ confessions it may be proved, sent abroad exceeding great numbers of intelligencers, spies, and practisers, into most princes’ courts, cities, and commonwealths in Christendom, not only to take and give secret notice of princes’ intentions, but to deal with the discontented of every state for the attempting of somewhat against their lords and superiors, namely against His Holiness and the King of Spain His Majesty, whose sacred persons they have sought many ways wickedly to destroy.

He may have been grimly amused at Allen’s charge of Machiavellian dealing.

Certainly Walsingham had used any instrument or method he believed was necessary to defend God, queen and country. One of these was the rack in the Tower of London. He called torture by its name: he did not hide behind euphemisms. He acted with absolute surety of purpose; he had few doubts. At her trial Mary Queen of Scots accused Walsingham to his face of working against her. Sir Francis replied: ‘I protest before God that as a man careful of my mistress’s safety I have been curious.’ This was a masterful piece of wordcraft, for though ‘curious’ meant in one sense attentive and careful, it also gave a meaning of something hidden and subtle. After many years of fighting a secret war against an unforgiving enemy, Walsingham captured his profession in a single adjective.

Walsingham knew full well the cost of his service, to which there is a sharp reference in his will. When he set out his wishes for a plain and simple funeral it was ‘in respect of the greatness of my debts and the mean state I shall leave my wife and heir in’. He had spent private money on public business, hoping for royal patronage to offset the burden. In Walsingham’s case the size of the debt was immense. When he died he owed to the crown the extraordinary sum of about £42,000, though it was established a few years later (thanks to the tenacity of his widow) that Elizabeth’s treasury owed him an even greater sum.

Walsingham committed a great amount of this money to espionage. His brother-in-law Robert Beale, with whom he worked closely in the royal secretariat, maintained that Walsingham paid over forty spies and intelligencers throughout Europe. He had agents in the households of the French ambassadors to Elizabeth’s court, from whom he gathered intelligence on France and Scotland. With money, Beale wrote, Walsingham ‘corrupted priests, Jesuits and traitors to betray the practices against this realm’. He ran a very efficient system of intercepting letters passing on the post roads of Europe.

Elizabeth’s government never entirely suppressed the exiles; that would have been impossible. But Walsingham’s efforts to disrupt and confuse them had a definite psychological effect. In February 1590 Sir Francis Englefield, one of Elizabeth’s most determined enemies, wrote of the ‘doubt and fear’ of his missing letters: ‘I have lost so many, and received so few, as the want of them disjointeth much my poor affairs’. Those letters can be read today in Walsingham’s papers. He and Phelippes may have taken a professional pleasure in knowing something of the confusion and uncertainty they could cause, frustrating and confounding the enemy.

As Robert Beale well knew, the key to Walsingham’s method was money. Beale used the word ‘liberality’, with regular demands for cash, pensions and patronage by spies, informants and merchant and diplomatic contacts abroad. Reporting directly to the queen, Walsingham kept his own secret accounts, explained by wonderfully vague phrases like ‘to be employed according to her Highness’s direction given him’. But the days of such liberality had, for the time being, passed.

On Walsingham’s death the queen did not appoint a new secretary. Instead Lord Burghley took on Walsingham’s reponsibilities, a painful burden for a man of sixty-nine years who suffered terribly with what he called gout. Yet Burghley had worked for a lifetime at the edge of his physical endurance. Powerful and grand, he had served Elizabeth once before as her secretary, occupying that office for over a decade, and by 1590 he had been Lord Treasurer of England for eighteen years. There was no area of government in which Burghley’s influence was not felt. Just before his death, when he was too sick to carry out his duties (probably in early 1590), Walsingham handed to Burghley his official papers on diplomacy, with special reference to England’s relations with Spain. There was also ‘The book of secret intelligences’. The contents of Walsingham’s secure cabinets moved to Burghley’s own.

He lost no time in reviewing the system for gathering intelligence he had inherited from Walsingham. Within at most three weeks of his protégé’s death Burghley looked at the work of five ‘intelligencers’ who had served Sir Francis in continental Europe. Burghley wrote out their names in his graceful italic handwriting. They were Chasteau-Martin, Stephen de Rorque, Edmund Palmer, Filiazzi and Alexander de la Torre. Henri Chasteau-Martin, a Frenchman whose real name was Pierre d’Or, acted on behalf of English merchants trading out of Bayonne. For reports on Spanish news he received an annual salary of 1,200 Spanish escudos (something around £300 sterling), a very handsome sum of money, paid to him quarterly by the London-based international merchant and financier Sir Horatio Palavicino. Edmund Palmer was placed in Saint-Jean-de-Luz. Stephen de Rorque worked in Lisbon. Filiazzi was close to the Duke of Florence. One Alexander de la Torre, who used the alias of Batzon, had moved from Antwerp to Rome in February 1590. This was not a large network of foreign spies and intelligencers, but it was an effective one, for these five men were placed at key ports and cities in France, Portugal and Italy.

Lord Burghley names his secret intelligencers in Europe, 1590.

The days of generous subventions for government espionage were over. Elizabeth’s exchequer was dry: there had to be cuts. As if to lead by example, Burghley only once claimed the secretary’s allowance of money for secret work, in May 1590, the month following Walsingham’s death. After that, Burghley either wanted to cut back on the work of Sir Francis’s agents and intelligencers or, more likely, asked them to sing for their suppers more sweetly – and more cheaply – than they had done before. Spies and informants had grown used to fairly rich pickings of cash and patronage. Ahead were leaner times.

For Burghley, agents’ salaries raised the matter of their reliability. It was the eternal question of value for money. With the help of the vice-chamberlain of the queen’s household, Sir Thomas Heneage, Burghley conducted a review, wanting to find out if the money paid to agents actually brought about useful intelligence. Drawing up secret accounts with Heneage, Burghley noted the size of Chasteau-Martin’s salary. Another agent, one sent by Sir Horatio Palavicino to Lisbon, received over £94. This agent was a great rarity: she was a married woman, the wife of one David Roures; she had received the money from Francisco Rizzio, Palavicino’s business agent.

But if Chasteau-Martin and the elusive Mistress Roures were worth the expense, then Edmund Palmer of Saint-Jean-de-Luz was not. After reading Palmer’s letters to Walsingham, Burghley’s audit exposed the amounts of money he had ‘pretended’ to use ‘for Her Majesty’s service’. Burghley also had doubts about another merchant, Edward James in Bayonne. James produced a copy of what he said were Walsingham’s instructions for two secret missions. One was to Madrid to secure information about the health of King Philip and the activities of Sir William Stanley, the rogue English military commander in the Low Countries who had defected to Spain in 1587. James’s second mission was to make a reconnaissance of the coastline of the Bay of Biscay. Whether or not Burghley was in the end convinced by Edward James and his work, he must have wondered about who could be relied upon to provide useful information, what they should be paid for it and whether espionage could be carried out on a much tighter budget than it had been by Sir Francis Walsingham.

But although Lord Burghley was the advocate of efficiency, he was also the most experienced of Elizabeth’s advisers, and knew probably better than anyone else the dangers to queen and country. For thirty years he had made it his business to get to know his mistress’s enemies. A couple of months after his audit, Burghley drew up his own report on the Catholic exiles and émigrés, making a special note of their Spanish pensions. Two were Charles Paget and Hugh Owen, chief intelligencer to the Spanish authorities in Brussels. Now dead, Burghley noted, was Lord Paget, that unwilling and melancholy exile, party to the Duke of Guise’s planned invasion of England in 1583, who had left behind him a vast fortune.

For Thomas Phelippes some of the old certainties were disappearing. Walsingham, his master, was dead. To whom now was he responsible? Already he was feeling the strain of paying the expenses of Thomas Barnes from his own purse, careful to keep the signed receipts. His family circumstances were changing, too. In 1590 William Phelippes, Thomas’s father, died at his house near Leadenhall in the city of London. To Thomas he bequeathed his gold signet ring and all his books, but not yet his fortune, which went to his mother, Joan.

But, like any gentleman with servants to pay, Phelippes needed money. Given the dangers as well as the costs of his secret work, he also needed a patron at Elizabeth’s court. His purse was only so deep, and he was too clever to leave himself exposed to the charge that he did freelance espionage without official sanction. He once made a tantalizing reference to the queen’s knowledge of his secret life: he had always gone about his business, he wrote, ‘not without the Queen’s privity [private knowledge] and approbation’. At first he may have tried to catch the eye of a patron with a sharp political essay on the ‘Present perils of the realm’. Here, like other clever men who wanted to show off their talents, Phelippes set out the evidence of the international Catholic conspiracy faced by Elizabeth and her kingdoms. Phelippes may indeed have looked to Burghley’s support, though given the fashion for austerity he did not get very far in receiving it, at least as a permanent employee.

But in the spring of 1591 there was another likely patron at Elizabeth’s court. He was twenty-five years old, aggressively ambitious, fashionable and rich. For long he had lived in the shadows of older men, especially the particularly large shadow of Lord Burghley, in whose household he was raised and educated as a royal ward after the death of his father in 1576. This young nobleman’s name was Robert Devereux, second Earl of Essex, and he wanted desperately to impress the queen. He knew nothing about intelligence work, a fact that made him the perfect patron for an old hand like Thomas Phelippes. Each man could do the other a favour. Essex could give Phelippes a job; Phelippes, the skilled spy, could give in return knowledge of the queen’s dangerous enemies.

The effort to recruit Phelippes to Essex’s fledgling intelligence service came from one of Phelippes’s obscure contacts, a man called William Sterrell, whose career (like many of Phelippes’s acquaintances) had so far in Elizabeth’s reign been a secret one. Sterrell wanted a job in the earl’s service and he needed Phelippes’s help to secure it. He threw himself at both men in the hope of preferment, attaching himself limpet-like to Essex. Phelippes, however, was a harder man to persuade. He was not really convinced either by Sterrell or for the moment by Essex. Not to be put off by Phelippes’s coolness, Sterrell pushed and pressed. He even invited Phelippes to dine with the earl at home. By May 1591 Sterrell was talking personally to Essex: ‘I had some little talk with my lord about you,’ he wrote to Phelippes, ‘which proceeded from himself.’

The proposal that formed within Essex’s circle over a few weeks was to use Sterrell to penetrate the network of English Catholic exiles in Flanders. The man who sought to negotiate the terms of this mission with Phelippes was the brilliantly polymathic Francis Bacon, thirty years old, the nephew of Lord Burghley, and a close friend of the earl’s. Moving in the same political circles, Bacon and Phelippes had known each other for a long time. Bacon had once been the companion of Phelippes’s younger brother Stephen. Bacon courted Phelippes, recognizing his abilities, acting as intermediary between Phelippes and Essex, proposing a meeting between them. Bacon wrote to Phelippes of their prospects for success: ‘I know you are very able to make good.’

The risks of joining the Earl of Essex and his men would have been plain to Phelippes. The reality of this new world of Elizabethan politics was vicious competition between Essex and other courtiers. Ambition, power and the scramble for royal patronage stimulated political faction. But after the Great Armada of 1588, in the hard years of war against Spain in the 1590s, intelligence work became more unstable and unpredictable than it had been before. Tied up with money and political standing it mirrored the politics of the Privy Council. True, the espionage system of Walsingham and Burghley was not perfect. Political agendas lurked even at the easiest of times, though there were precious few of those in Elizabeth’s reign. But at least there had been something like a clear organizing intelligence behind the government’s clandestine work; it was effective by its own standards and methods; and Walsingham and Phelippes, who rarely rushed even at times of high anxiety and emergency, delivered results. Essex was different. Espionage became for Essex an instrument for his political advancement. Phelippes surely knew that ahead lay danger.

In this world where loyalties were tried and tested, made sure of or found wanting, Essex had to know where Thomas Phelippes’s allegiance lay. Lord Burghley, too, put his trust in Phelippes’s expertise, writing in 1593 of a letter in cipher and appealing to Phelippes’s loyalty. The packet, dispatched in Dieppe, came from ‘a bad affected person resorting often times to the enemy’. It was addressed to Phelippes. Burghley’s test was to send it to Phelippes unopened. It was an act of faith on Burghley’s part, using Phelippes’s skill to decipher the letter and relying upon Phelippes’s honesty to alert him to any significant piece of intelligence contained in the packet. As Burghley wrote: ‘I would not open the same, being assured of your good and sound affectation to the state and Her Majesty’s service, that if there be any matter therein, fit to be discovered, that you will not keep it secret.’

How would Thomas Phelippes conduct himself in treacherous times without the safety and security of his service to Sir Francis Walsingham? To this question the Sterrell case would within months suggest the answer.