In 1591 William Sterrell pestered Thomas Phelippes to recommend him for service in the household of Robert Devereux, the young and ambitious Earl of Essex. Sterrell was convincing and plausible and soon found himself in the earl’s employment. Phelippes was less willing to join Essex but, left by Walsingham’s death without a patron, he had few other choices open to him. After some months of courtship, Francis Bacon, Essex’s great friend, at last recruited Phelippes and his vast experience of operating secret agents.

Essex wanted to dazzle the queen with a great intelligence coup against Her Majesty’s enemies. He had high expectations and he wanted results. But Sterrell’s mission in Flanders, which was launched by Phelippes in the spring months of 1592, failed, at a cost to Essex’s purse and also his patience. It was the ruin of Sterrell. And it damaged Phelippes’s reputation for skill in espionage, most importantly of all in the eyes of the queen herself. In fact, it was the greatest failure of Phelippes’s long career in the shadows of Elizabethan government.

The setting for the mission was Europe: Antwerp, Brussels, Liège and London. Nothing of the whole paraphernalia of Elizabethan espionage was missing from the Sterrell case. There were aliases (Sterrell alone used at least two), plausible cover stories, secret postal addresses in three European cities, a cipher and meticulous arrangements for the exchange of money. At first one and later two couriers worked for Phelippes and Sterrell, both Yorkshiremen, Reinold Bisley and Thomas Cloudesley. Both men were believed by the Catholic exiles to be their agents, but they were deceived by Phelippes’s arts of double-cross. To each and every aspect of the mission Phelippes gave time and effort. A startlingly accomplished man himself – the best breaker of code and cipher in western Europe, a Cambridge-educated mathematician, a linguist fluent in five languages, a shrewd judge of men – he was supported in Sterrell’s mission by Francis Bacon, one of the most prodigious intellects in Elizabethan England. And yet for all this, so technically brilliant an operation produced no worthwhile intelligence on émigrés in the pay of the King of Spain. What should have been a wonderful success for the greater glory of the ambitious Earl of Essex became for reasons of personality, circumstance and politics a confused tangle of misunderstanding and bitter recrimination.

The proposition, which employed Phelippes’s familiar method of using a double agent, looked at first so promising. William Sterrell, a veteran of espionage in the Low Countries during the time of Walsingham, would work in Brussels and Antwerp to gather intelligence on the queen’s enemies in Flanders, offering himself as a likely agent for Catholic émigrés who wanted to recruit an English spy. Sterrell’s reports, carried by the courier Thomas Cloudesley, would be delivered to the Swan inn on Bishopsgate, just outside the city walls of London. Phelippes, who had a network of contacts in the city, would collect them from the Swan.

So convinced was the Earl of Essex of certain success, he briefed the queen on Sterrell almost before he was launched; he wanted to lose no time in showing to Elizabeth the impressive skills of his men. Even Phelippes, by nature a cautious man, was hopeful of being able to get good intelligence on important exiles. Of the émigrés three were especially dangerous: the renegade military commander Sir William Stanley; the clever Catholic intelligencer Hugh Owen; and Henry Walpole, a Jesuit chaplain in Stanley’s regiment.

Phelippes wrote a passport for Sterrell that would allow him to pass easily through ports on both sides of the English Channel. His cover was trade; he was supposed to be the agent of a London merchant. Phelippes gave him £10. Essex was at first relaxed about the sums of money he would need to provide to fund the mission, though Phelippes well knew that these were more modest than Sterrell had hoped for. The earl nevertheless felt generous. As he wrote to Phelippes: ‘I would wish to have full contentment in these things with no pity of my purse.’ He was making an investment, expecting a quick return on his money.

Sterrell’s first reports seemed very promising. He took his cover seriously, and wrote to Phelippes as a merchant’s factor might write to his master. But woven into the letters were passages of cipher. Surely it was no surprise to have confidential matters of business protected in this way. In fact, Sterrell was making his secret briefings to Phelippes. One of the first of these hidden messages concerned a plot to kill the queen. Sir William Stanley, Sterrell wrote, had sent into England ‘one Bisley by [i.e. by way of] Flushing, sometime a soldier there, a little short black fellow, a red face, his father an officer in York.’ This was not, however, the major revelation Sterrell may have imagined it to be. As it happened, Phelippes already knew of Master Reinold Bisley, whom he had kept under close surveillance for some little time.

Phelippes’s subtle mind was thinking of Bisley and the uses to which a soldier-assassin might be put. Sterrell, however, was much more preoccupied with the hardships of his new secret life abroad. He was bothered about money, feeling that he could not live in Brussels for less than £140. For a start, he was not yet dressed in the Spanish fashions of the city’s elite, which he felt hindered his gathering of intelligence.

Soon he left Brussels for Liège and then he went to Antwerp. There the factor of the merchant who had been approached by Phelippes to exchange Sterrell’s money said he knew nothing about the agreement; Sterrell instead made his own arrangements with a merchant from Cologne. There were difficulties, too, of communication. Phelippes, who understood the risks of sending letters from England to mainland Europe, was going to the trouble of cutting his letters to Sterrell into two halves and sending each part separately. Sterrell, however, received only some of the packets. Knowing there was a valuable market in Antwerp for intercepted letters, Sterrell wrote to Phelippes:

Send me word always how many letters you receive with the date, that I may know if any miscarry. Let me know what was in your letter sent to the master of posts in Antwerp for it is intercepted; there is no letter can pass under any known name but will be filched by one or other; here is such extreme emulation or envy. Write all matter of importance in cipher.

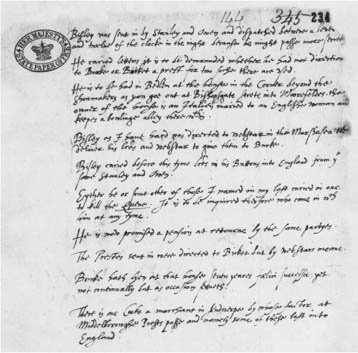

The secret report on Reinold Bisley written for Thomas Phelippes, 1592.

And yet in spite of all this trouble Sterrell told Phelippes that he was sure he could find out valuable intelligence. He wrote that he could even intercept the letters of Cardinal William Allen, that most influential of English exiles working for Spain: if only, of course, he had some more money.

Reinold Bisley, named by Sterrell as an assassin on the way to England to kill the queen, was certainly a suspicious character. In the weeks before Sterrell left for Brussels Phelippes had had him watched; perhaps even then Phelippes had imagined a use for him in Sterrell’s mission. Phelippes’s watcher found Bisley at his lodgings near Bedlam. It was a house owned by an Italian who kept a bowling alley, one of those haunts of bawkers, gripes and vincents – Elizabethan underworld slang for players, gamblers and dupes – that so offended the high standards of Elizabethan moralists.

Phelippes’s informant spent time and effort gathering as many facts as he could about the mysterious Bisley. The watcher’s information was that Master Bisley had been sent to London by Sir William Stanley and Hugh Owen. He had arrived in London in the middle of the night and in conditions of great secrecy. Moving between Antwerp and London, Bisley worked as a courier who carried the letters of Stanley and Owen ‘in his buttons’ – that is, strangely, without any effort to conceal them. The subject of one of these letters, so the watcher reported to Phelippes, was the murder of Queen Elizabeth.

In fact Reinold Bisley was an English spy who worked for Lord Buckhurst, one of Elizabeth’s privy councillors who knew a great deal about the Low Countries. Bisley was not, in other words, a dangerous Catholic: he carried a paper signed by Buckhurst and was employed secretly in the queen’s service. All of this Phelippes discovered when he interviewed Bisley in July 1592, two months after Sterrell had left for the Low Countries. Bisley told Phelippes that he was a simple courier, bringing letters from the émigrés and then delivering them in London and Southwark. Certainly he knew Sir William Stanley and Hugh Owen. They believed that Bisley was posing as a spy for Elizabeth’s government: that, in other words, he was their double agent. His allegiance, however, was to Lord Buckhurst, and Owen and Stanley were convinced by the deception.

Phelippes’s careful account of his interview with Bisley shows that he was wary of the dark-haired Yorkshireman. One of Phelippes’s sentences is particularly pungent. He wrote of Bisley: ‘He will as others have done make his profit of me at one time or other.’ And yet for all the warning he gave himself, Phelippes chose to take the risk of employing him. An excellent second courier for Sterrell, one who was trusted by the very men Phelippes wanted to spy on, had fallen into his lap. It was the kind of double-cross Phelippes relished.

By late summer 1592, only a few months after he had set out for Brussels, Sterrell and his mission were in trouble. Exactly why is a mystery, but it seems he panicked. Francis Bacon wrote to Phelippes that ‘Mercury’ was returning home in alarm, the news was known at court, and the Earl of Essex had been informed. Bacon’s allusion to classical myth and astronomy was an ironic play upon Sterrell’s cover in Brussels and Antwerp as an English businessman. The planet Mercury was specially associated with feats of skill, eloquence and success in commerce, and to the Romans Mercury was both a messenger and a god of trade. Sterrell, however, was proving himself considerably more inadequate than a god of the pantheon in his abilities as Essex’s master spy.

For some time now, Bacon had been working closely with Phelippes, though Bacon’s references to the time they spent together have all the elegant ease of a scholar only passingly aware of the world around him. In August he invited Phelippes to call on him. ‘You may stay as long and as little while as you will,’ Bacon wrote. ‘And indeed I would be the wiser by you in many things, for that I call to confer with a man of your fulness [prosperity, affluence].’ We can be sure that there was a very definite sense of purpose to a visit by one of the most cunning men in England to probably the kingdom’s most intellectually gifted.

Bacon said that Sterrell had returned so unexpectedly to England ‘upon some great matter’. Probably this was fear, for from the beginning of his mission he had felt exposed in enemy territory, short of money and very worried about the interception of his letters. ‘I pray you meet him if you may,’ Bacon wrote to Phelippes of Sterrell in September. Bacon suggested that he and Phelippes should lay their heads together so that they could save Sterrell’s reputation, satisfy the demands of the Earl of Essex and ‘procure good service’.

But already the damage was done. Sterrell returned to court without official approval. Essex was furious that Lord Burghley, with eyes and ears everywhere, had known of Sterrell’s homecoming two days before Phelippes. The earl was particularly embarrassed that after talking of the mission is such glowing terms to the queen he was beginning to be asked uncomfortable questions by her about his agent. Even when Sterrell had sent reports, Essex wrote bitterly to Phelippes, they had ‘no satisfaction of anything of worth’. In the highly charged politics of Elizabeth’s court, Sterrell’s short stay in Brussels and Antwerp was beginning to have about it the quality of a heavy albatross, and this only months after its inception. But even Essex, annoyed as he was, was not without hope. He told Phelippes that he thought Hugh Owen’s messenger ‘carrieth some probability of good service’. Essex meant here Reinold Bisley. About a month after their first interview in July, Phelippes had successfully recruited Lord Buckhurst’s spy to Sterrell’s mission.

The Earl of Essex’s temper did not improve over the spring and summer months of 1593. He was as dissatisfied as ever with Sterrell’s lack of productivity. He wrote sharply to Phelippes of the damage being done to his standing at court: ‘my reputation is engaged in it’. He feared the queen’s ‘unquietness’ (her disturbance or restlessness) and his own disgrace. This, as Essex would not have been prepared to admit, was the swift and heavy cost of making intelligence an instrument of political advancement. It was certainly not what Essex had imagined when through Francis Bacon he had recruited Phelippes to oversee a brilliant intelligence coup whose purpose was to impress the queen.

With Sterrell now in England it was the couriers, Cloudesley and Bisley, who went abroad with letters to his émigré contacts. Phelippes grimly soldiered on in a lacklustre operation. With the plague ‘hot in London’ in the first week of July he wrote to Sterrell, safely out of the city, with instructions for what he should write to his enemy contacts abroad. Letters in cipher were duly dispatched to the continent, but for all of these efforts no information of any value was uncovered. It was a masterclass in the futility of technique over substance, and Phelippes knew it.

Sterrell frankly blamed Cloudesley and Bisley for his poor results. Through Cloudesley’s clumsiness, Sterrell told Phelippes, secret letters had been delivered to the wrong men, which, given the factional squabbling among the émigrés, he felt put at risk the whole operation. True, he could not fault Cloudesley’s standing with the men they were spying upon; they trusted him. To Phelippes Sterrell hoped their courier had not ‘played the knave with us’. Sterrell had even less faith in Reinold Bisley, who he was sure had counterfeited and deceived them. Phelippes’s view was different. He was moderately confident in the loyalty and ability of the two couriers.

Surprisingly it was Sterrell, not Phelippes, who was right – or at least Bisley, the humble courier, who first felt the sting of the operation’s failure. By September 1593 he was a prisoner in the Gatehouse prison in Westminster, accused of duplicity in his dealings with Sterrell. At their first meeting just over a year earlier Phelippes had been very wary of Bisley: ‘He will as others have done make his profit of me.’ Fourteen months later, however, he petitioned the queen for Bisley’s release from jail. In fact he really had little choice. The unpleasant fact was that Phelippes’s reputation was now tangled up with Bisley’s. Phelippes approached Elizabeth through Lord Buckhurst, whose agent Bisley had been. It was a chastening experience. Buckhurst told Phelippes plainly that the queen was annoyed with him. Buckhurst had done his best for Phelippes by giving Elizabeth ‘general assertions’ of his ‘sufficiency, fidelity, and great care and diligence used in Her Majesty’s service’. The queen was unmoved by Buckhurst’s character reference.

But for Phelippes, and even for Bisley, there was hope. Briefed by Lord Buckhurst, Elizabeth knew something of Bisley’s secret service. Annoyed as she was, she felt that he should be put to work, though she left the details of what kind of work this might be to Phelippes and Bisley to decide between them. This was thanks to Buckhurst, who had advised Elizabeth that Bisley could do ‘good service’. But without money he had no hope of success. Buckhurst asked the queen for £20 to pay most of the bill of £21 Bisley owed to the keeper of the Gatehouse for his board and lodgings in prison. She offered £10 only, with the promise of her ‘princely reward’ in the future. Elizabeth left it to Phelippes to tell Bisley that, as he had dealt so badly with Her Majesty, she had no reason to give him any greater reward until he deserved it.

A fortnight later Phelippes sent his servant to the Gatehouse to pay the £10 given by the queen to cover just under half of Reinold Bisley’s prison bill. Phelippes, for reasons we may guess at, showed no great willingness to cover from his own purse the £11 outstanding.

To the Earl of Essex the failure of Phelippes’s work with Sterrell meant political embarrassment. In a few months Sterrell had produced nothing of any significance, and the earl was not prepared to sit patiently by for success to come. Quickly he held Phelippes to account. Essex felt he had wasted money, time and effort. He had wanted speedy results: good intelligence he could take to the queen, for which at the beginning he was willing to pay generously – though not so generously as Sterrell may have wished. What he got instead from his investment was damage to his reputation at Elizabeth’s court. All there was to show for Sterrell’s work by 1593 was a hefty pile of inconclusive letters and reports. The experience and cunning of Thomas Phelippes had not given the earl the dazzling success he wanted. With the impatience often characteristic of powerful men, Essex redirected his interests from the Low Countries to espionage in France.

It was Sterrell who felt above all the sharpness of Essex’s displeasure. Without results there was no money. He wrote plaintively to Phelippes that he was cast out of the earl’s service; he was now only a ‘voluntary follower’ of Essex with neither wages nor security. The earl had promised him that he should have his horsemeat for free, but he was having to pay for it himself. He was no longer even able to afford properly to pay his manservant. So much for the life he had expected in Brussels, that of a gentleman spy dressed in the latest Spanish fashions. He had nothing. But, he wrote to Phelippes, he bore these indignities. He was miserably resigned: ‘I am out of heart more than you think for.’

No one knew better than Thomas Phelippes that William Sterrell had failed to gather any useful information on the queen’s enemies abroad, those fugitives in the pay of the King of Spain who plotted against England and sought Elizabeth’s destruction. The operation, as Phelippes and probably also Francis Bacon conceived it, was in principle simple enough: to send a man to Flanders to spy on the émigrés under the cover of trade. Everything had been worked out with such care, from the aliases Sterrell and Phelippes would use and the courier system they would employ to the means of getting money abroad. But Sterrell, though he knew something of the Low Countries, was quickly out of his depth; he bolted, worried for his safety. The mistakes and possible duplicities of the couriers Cloudesley and Bisley compounded Sterrell’s failings. The enormous political force being applied to Phelippes made it practically impossible to take his time in working with Sterrell, Cloudesley and Bisley. Phelippes was used to working over years, not six months. But in the end the plain fact is that Sterrell, who had been exceptionally able in convincing Essex of his merits, could not cope with the strains of the mission. Probably Phelippes had known this all along, just as he was suspicious at first of Reinold Bisley. But Phelippes showed great loyalty to his agents, however flawed they were.

And yet his failure with Sterrell rankled, and even as late as 1596, four years after the operation began, he could not quite let it go. He wrote to Essex with a review of what had gone wrong. Though polite by the formulae of Elizabethan correspondence, the letter has a sharp edge to it, and for a very good reason: Phelippes suffered the humiliation of seeing the reputation for efficient and effective service that he had built up over many years so quickly drain away. He was plain with the earl. For the queen’s service, he wrote, he had opened up intelligence between Sterrell and English fugitives in the Low Countries. As he was unable to support the mission out of his own pocket, the operation was lost through the failures of the men Essex had used to manage it. Phelippes believed that the fault lay in what he called the want of good handling. What pained him most was that the queen, who disliked both Sterrell and his mission, believed that it was Phelippes who made errors of judgement. Phelippes, in other words, found himself in an extraordinary political tangle the like of which he had never experienced before.

Phelippes was finished in Essex’s service. It also seemed highly unlikely that, with his talents now tarnished by the Sterrell case, the Cecils would employ him in any regular way. True, in July 1594 he untangled for Lord Burghley a confused diplomatic cipher. A year later he deciphered, once again for Burghley, a letter intercepted from the enemy, using this opportunity to advertise his expertise: ‘the comparison of other intelligence I have had of the factions and proceedings of them on the other side’. The hint (in the circumstances a fairly subtle one) did him little good.

Some time after his father’s death in 1590, Phelippes had been appointed to an official position in the London customs house, the kind of office that helped to keep smoothly running the wheels of royal patronage. With no fortune of his own, Phelippes took full advantage of his highly remunerative post, though at a catastrophic cost to his good name. He accumulated a debt of nearly £12,000 from customs revenue he had collected and appropriated but which by 1596 he could not afford to pay to Elizabeth’s treasury. It was an almost incomprehensible mistake for a man of Phelippes’s ability to make. But he could not escape from the consequences of his recklessness. The queen’s mild annoyance at his failures in the Sterrell affair was as nothing to her fury over Phelippes’s mishandling of her money. For the first time in his life, at about the age of forty, Phelippes saw the walls of a cell as a prisoner, not as an interrogator. He went to jail in 1596. Though released in 1597, he was soon returned again.

He found it a long, hard road back to service. Bruised by the court politics of the 1590s and burdened by his debt to the queen, he gathered his reserves of energy in the early months of a new century. Chastened by his past failures, Phelippes hoped to win the favour of Sir Robert Cecil, by now the extraordinarily able and influential secretary to the queen. Phelippes went first of all to an intermediary, William Waad, who also ran secret agents; the two men had known each other for a long time. To Waad he made what he called his ‘overture’. Phelippes wrote that in spite of his troubles of the last few years he had with the queen’s knowledge stayed in touch with intelligence matters. Even in prison he had broken enemy ciphers. He felt that the time had come to put his expertise properly to use.

At first he had no reply, so in the early spring of 1600 he plucked up the courage to write to Sir Robert directly. Always a perfectionist, he spent four days getting his letter to Cecil right. We know this because two copies of it exist, each with different dates written in Phelippes’s tiny, precise hand. He had tested every word and sentence, trying to find just the right tone, both contrite and persuasive. This, as Phelippes knew very well, was the hard business of political patronage and favour. At last he sent the letter to Sir Robert on Friday, 18 April 1600.

Phelippes pardoned his presumption. He knew, of course, that Sir Robert had ‘so many spirits and endeavours of the whole kingdom at your commandment’; but, encouraged by others who had been lucky enough to receive Master Secretary’s favour, he was bold to offer his service. Phelippes had all the necessary skills. Most important of all was trust: the trust of those agents he worked with and that of the men he worked against. As Phelippes put it: ‘the principal point in matter of intelligence, is to procure confidence with those parties that one will work upon, or for those parties a man would work by’.

Thomas Phelippes’s offer of secret service to Sir Robert Cecil, April 1600.

And so he offered to Secretary Cecil his service and talents: ‘I will be glad and vow unto you to employ that dexterity I may have to the utmost of my power.’ He ended craving pardon of his boldness, ceasing to trouble Sir Robert further.

Cecil replied to Phelippes in his own hand, a fluent, easy response to Phelippes’s formal and carefully crafted prose; it made all the difference to be a magnanimous patron rather than an anxious suitor. Sir Robert wrote:

I thank you for your offer to employ yourself in Her Majesty’s service with my privity and direction; for the means you have yourself can judge; for the mind you have I know it of old and do allow it. And where you desire my favour, if you do make your services fruitful assure yourself I will very gladly do you any pleasure I can; and when you will come to me, I would confer with you of your projects …

For Phelippes this was a remarkable recovery. His debt to Elizabeth’s treasury still hung over him; he never repaid it. But Sir Robert, in recognizing Phelippes’s talents and expertise, had doubtless done much to heal the bruises of the Sterrell affair. Phelippes set to work straight away with energy and passion, using his old contacts abroad to discover the intentions of England’s fugitive enemies: ‘to feel their pulse on the other side’, as he put it in a lively metaphor.

And so Phelippes survived. If he was not prosperous in the years after 1600 he was certainly busy. He was in Sir Robert’s favour and protection – at least for the time being.