THE CLASSIC PERIOD

The transition from the Formative stage (Mesoamerican Preclassic period) cultures to the Classic period cultures was gradual. It was marked more by the appearance of superlatives—in architecture, thought, writing, crafts, and so forth—rather than the appearance of new phenomena. The Classic achievements represent a cultural florescence, a time of the flowering of culture, stunning in its magnificence and variety. In this chapter I will attempt to outline the major features of the Mesoamerican Classic. The magnitude of the Classic achievement can be understood from simple statements concerning the size of the sites considered. Teotihuacan, for example, was an urban center covering 8 square miles with a population estimated at 75,000 to possibly 200,000 (Millon 1970). At Tikal the great temples on their pyramidal bases rise to a height of 60 meters above the plaza level. Monte Alban has a central plaza the size of a modern football field surrounded by a complex of buildings which has been undergoing annual excavation and restoration for more than 30 years.

In Figures 15-1-15-3 we present a set of maps locating the major sites by period and region. There are at least a hundred ceremonial centers which may be termed major and hundreds more that were of lesser size and importance. Cultural chronologies have been worked out for many of the major regions of Mesoamerica (Fig. 15-4). The regions included are the Northern Frontier and West, Central Mexico, Oaxaca, Maya Highlands, Huasteca, Central Veracruz, Southern Veracruz and Tabasco, Maya Lowlands, and the Southern Periphery. Less well known areas possessing Mesoamerican culture include Chihuahua, Guerrero, the Mexican west coast north of Colima, as well as parts of Nicaragua and Costa Rica.

The best known and most impressive regional cultures of the Classic are those of Teotihuacan in the Valley of Mexico, the Zapotec culture of the Valley of Oaxaca, the Mayan culture of the Guatemalan highlands and the Mayan culture of the Yucatecan lowlands. The wealth of the Mayan culture was so overwhelming that the Carnegie Institution established a major program of study under the leadership of Sylvanus Morley. For more than 30 years various Mayan sites were studied in detail; for example, sites of the first order of magnitude termed “metropolises” by Morley and Brainerd (1956) include Uxmal, Chichen Itza, Tikal, and Copan. Centers of the second class termed “cities” number approximately 20. The Carnegie efforts resulted in major excavations at most of these sites. The results include not only studies of the entire cities but detailed excavation reports of individual buildings (Morris 1931; Ruppert 1935), frequently several hundred pages in length.

Prior to the detailed archaeological excavation programs of the twentieth century, there was nearly a century of explorer and antiquarian interest in Mesoamerican ruins. The Mayan country was of primary interest inasmuch as the jungle was filled with “lost cities," any one of which could provide new and unique finds. These explorations, which are still continuing, such as the recent Explorers Club-sponsored survey of Guatemalan caves, first began in 1839 with the landing at Belize, Honduras, of John Lloyd Stephens, a New York lawyer, accompanied by Frederick Catherwood, an English illustrator. Previously Stephens had had good sales of a travel book he had published in 1837 concerning his visit to Arabia and Palestine. The trip to Central America was undertaken as a result of Stephens' learning of the ancient cities to be found there and the possibility that they could form the subject of another book. Eventually published in two volumes, Stephens' Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan (1841) provides our earliest detailed descriptions of ancient Mayan ruins. Catherwood's illustrations are priceless because they were uniquely accurate copies of the ancient buildings and monuments with their, at that time, undecipherable hieroglyphs. At the time he was copying these monuments, most European illustrators were adapting aboriginal peoples and archaeological findings in their illustrations to fit preconceptions largely derived from the ancient Classical world. Catherwood's renditions were accurate and further provide us with a record of the condition of the ruins prior to modern restoration.

In the last half of the nineteenth century, explorers and students expanded our knowledge of the ancient cities, for the most part without undertaking major excavations. Including Guillelmo Dupaix, Arthur Morelet, E. George Squier, Desire Charnay, Alfred P. Maudsley, Teobert Maler, Edward EH. Thompson, and others, these pioneers made known to the world the ancient splendors present in the Central American jungles (Wauchope 1965, Deuel 1967). Since their day, archaeological research has focused on problems in the following general order: 1. site location, 2. chronology based on the calendrical dates, 3. architectural studies and building reconstruction, 4. ceramic seriation, 5. radiocarbon dating and the calendrical correlation problem, 6. detailed site and regional mapping of urban developments, 7. studies of the economy, and 8. studies of social organization.

URBANISM AND SETTLEMENT PATTERN

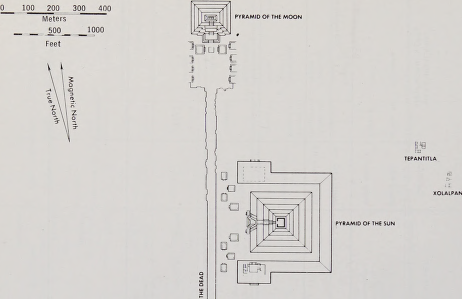

The Classic featured the rise of urbanism for the first time in the New World. Our best evidence of urban developments comes from central Mexico. This development seems to have been environmentally conditioned, for the heavily forested jungle areas witnessed a different pattern. Our best evidence of urbanism comes from Teotihuacan. Long known as an urban center, recent studies conducted on the Teotihuacan mapping project reveal the growth of the city period by period. Teotihuacan is unique in that it was built according to an overall city plan. It was laid out within a central valley location surrounded by an encircling set of low mountains. The city plan features a major north-south street, the Street of the Dead, which runs the full length of the city. Other major structural units include an east-west street, a ceremonial center featuring many major pyramids and temples (Fig. 15-5) and an extensive residential district made up of clustered one-story apartments. There were more than 2000 such apartment compounds within the city at its maximum extent— some 20 square kilometers (8 square miles). Two opposing structures, the Ciudadela and Great Compound (Fig. 15-5, Nos. 3 and 6) face each other at the intersection of the Street of the Dead and the east-west avenue. It is believed these structures formed the bureaucratic, ceremonial, and commercial center of the ancient city. The residential units were set off into barrios or neighborhoods, some of which were segregated housing for craft specialists. The religious structures associated with these compounds imply that the local residents cooperated in ritual activities. Population in the apartment complexes is estimated at 20 to 100 persons per compound, a group likely related by kinship. Most of the workshops were for obsidian, with others for ceramics, stone, figurines, lapidary work, and work in basalt and slate. The overall impression of a basic city plan is supported by the recent detailed mapping. Planning was certainly present throughout the city and not just in the central core area.

Another major function of the city was as a marketplace and center for

100

Fig. 15-1 Major sites of: *—the Preclassic period; **—Classic; ***—Postclassic (Willev 1966:Fig. 3-10.) ' y

Mesoamerican Archaeological Sites and Regions

1 Sierra Madre Oriental region of Tamaulipas

2 Sierra de Tamaulipas region

3 Tehuocdn Valley

4 Islona de Chantuto

5 CHiapo de Corzo

6 Ocos

** 7 Kaminal|uyu

8 Tampico-Panuco region •*** 9 Valley of Mexico

* 10 La Venta

* 11 Tres Za poles

* 12 San Lorenzo **13 Monte Alban

14 Izapa

15 El Baul ** 16 Uaxactun ** 17 T iko I

18 | Altar de Sacnficios |

** 19 | Piedras Negras |

** 20 | Palenque |

21 | Yaxchila'n |

22 | Benque Vieio |

23 | Lubaantun |

** 24 | Copan |

25 | Oxxkintok |

26 | Dzibilchaltun |

27 | Cobd |

** 28 | Uxmal |

** 29 | Ta|in |

* 30 | Cerro de las Mesas |

31 | Cempoala |

32 | Remoiadas |

*** 33 | Tula |

*** 34 | Mitla |

*** 35 | Chichen Itzd |

*•*-><36 Mayapan

37 Tulum

38 Yarumela

39 Tamuin

40 Acapulco

41 Apatzingan region

42 Ixtldn region

43 Alta Vista de Chalchuites

44 Schroeder

45 Yaxund

46 Zacualpa

47 Tazumal

48 Tzintzuntzan

49 Ortices

50 La Quemada

51 Rio Bee

52 Xpuhil

long distance trade. The combination of trade, religious ceremonialism, and workshops all led to an intense urbanization unique in Mesoamerica. Figures presented by Millon (1970) are that a minimal population estimate would be 75,000, with 125,000 more probable, and 200,000 not entirely unlikely. It was the most urbanized city in Mesoamerica during the Classic, and its power and influence were equally impressive. It was not until the rise of the Aztec in the Postclassic period that a comparable urban center existed in Mesoamerica.

The Mayan Settlement Pattern

The central feature of Mayan cities are the ceremonial structures faced with cut limestone masonry. They include large pyramids and platform mounds of earth and rock fill. The pyramids with temples on top are often high and steep and even with the decay of centuries are impressive indeed (Fig. 15

Other major buildings included ball courts, palaces, and rarely, round buildings, some which were astronomical observatories. The basic ceremonial center plan was the rectangular plaza surrounded on three or four sides with

I

t

Z)

o

c E

<

<

o £

5 cc

O CJ w < CE

Q. CD a N D

CO LU

Q 2; 2 O

I

O

X

<

>

<

<

o

<

X

<

o

o

o

<

cc

o o o ~

a 0) D J

< <

LU <

X - >

^ Ql ^

Fig. 15-4 Mesoamerican regional chronologies (Willey 1 966:Figs. 3 8 and 3 9.)

Cultural Data Revealed by Archaeology

386

YAYAHUALA

ZACUALA PALACE

£

pa

pt-QP VIKING GROUP

&

CIUDADELA

Fig. 15 5 Map of the ancient urban center of Teotihuacan, near modern Mexico Citv (Willev 1966:Fig. 3-40.) y

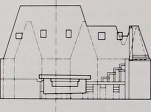

Fig. 15-6 a. Plan of the central section of Tikal, Guatemala. (Morley and Brainerd 1956:Plate 32.) b. Reconstruction drawing of Temple 2 at Tikal. (Hester photograph, courtesy Mexican National Museum of Anthropology.)

pyramids and platform mounds. Through time the central plazas grew by accretion until they formed a type of acropolis. Proskouriakoff (1946) has provided a reconstruction of this type of development for structure A-V at Uaxactun where eight successive stages of construction are revealed. Other features of the ceremonial centers include causeways, the erection of stelae at the base of stairways fronting on a plaza, and in Yucatan, sacred wells called cenotes. Evidence suggests that the inhabitants of the residential units, the palaces, may have been a hereditary elite. The common people primarily lived in small villages scattered throughout the farmlands. Their villages consisted of small one-room thatched structures frequently built on small earthen or stone platforms. The residents of several villages would cooperate in the building and maintenance of the regional ceremonial center.

A current controversy concerns the degree of urbanism of the major ceremonial centers. Earlier arguments asserted that the economy was based on the milpa system, a practice of clearing small fields which were farmed for two or three years and then abandoned for six to eight years. This is the modern system used in the area today, and it leads to a dispersed settlement pattern of low population density. If the milpa system was utilized prehistorically, then the ceremonial centers should not have been urban. Recent studies at Tikal, Dos Aguadas, and Barton Ramie reveal population estimates of 575 to 1600 persons per square mile, while the modern density is 25 to 100 persons per square mile (Culbert 1974:41—42). William Haviland (personal communication, 1974), who conducted the estimates at Tikal, reports there were 40,000 commoners living there. Clearly additional subsistence practices must have been employed. Culbert (1974:47 — 51) suggests that the elite may have enforced a shorter fallowing cycle—which would have increased yields by 28 percent at the expense of a 60 percent increase in labor. Planting of other crops besides corn could have increased the total yield. Possible food crops include yams, sweet potatoes, manioc, and the breadnut tree. The swampy areas might also have been farmed through the construction of ridged fields. While the evidence is as yet unclear, it seems that the Mayan ceremonial centers were more urban than we have previously thought.

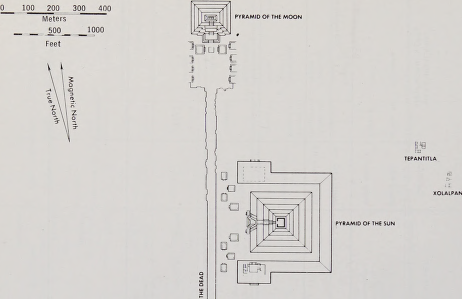

A recent study by Marcus (1973) emphasizes the organization of the Mayan settlements into a hierarchical network. According to emblem glyphs, the four regional capitals in A.D. 731 were Copan, Tikal, Calakmul, and Palenque. In A.D. 849 the four capitals were Seibal, Tikal, Calakmul, and Moutul de San Jose. The four capitals fit the Mayan concept of the universe which was divided into four directions and the center, each with its own color, flora, fauna, and deities. Each regional capital was linked with a series of secondary centers, yielding a hexagonal settlement pattern (Fig. 15-7). The secondary centers in turn had their own satellites in a similar pattern. The pattern, while based on cosmological considerations, was also in part the result of functions to be provided by the centers—trade and transport. A final determinant was the linking of the regional capitals with the secondary centers through royal marriage alliances. Marcus further suggests that since the hexag

Mesoamerican Civilization

389

Fig. 15-7 Mayan settlement patterns, a. Relationships between an actual regional capital, Tikal, and its secondary centers, b. Schematic diagram of the Mayan settlement pattern: circled stars= regional capitals; 2s= secondary centers; 3s=tertiary centers; dots= shifting hamlets. (Marcus 1973: Figs. 6 and 8.)

b Eastern capital

Western capital

onal patterns are of unequal size the relationship may have been based on population rather than geographic area. The organization within each quadrant featured a five-tier hierarchy of capital, secondary center, tertiary center, village, and hamlet. Coe (1 967a) states that each community down to the village level was divided into quadrants, the tzuculs , wards made up of exogamous patrilineages. However, according to Haviland (personal communication), Coe's hypothesis has never been borne out.

ARCHITECTURE

Architecturally, the Mayan buildings are superlative. Many were specialized for religious functions and therefore did not need to be spacious or hospitable. Major general features of Mayan buildings were that they were thick walled, built on top of massive pyramidal platforms, and featured little interior space, with the rooms being dark, narrow, and high ceilinged (Figs. 15-8 and 1 5-9).

Pyramid of Inscriptions, Palenque

Elevation, section and plan 1:750

Crypt of the Pyramid of Inscriptions

Plan, section and elevation 1:200

0 2 5 1 0

Fig. 15 8 Plan and elevations of the Pyramid of the Inscriptions, and of the crypt beneath the pyramid. (Stierlin 1964:46.)

Above the rooms extended an incredibly heavy stone roof, made necessary because of the lack of knowledge of the true arch. They used the corbeled arch made of stones cantilevered toward the center, which necessitated enormous quantities of stone. Above the roof lines so constructed were intricate decorative features including roof combs, flying facades, and sculptured friezes. Within the temples there were occasionally decorative panels, such as those in the Temple of the Foliated Cross at Palenque. These panels were carved in basrelief or had mural paintings, of which the outstanding example is Bonampak.

Fig. 15-9 Architectural details of Mayan buildings at Uxmal, Guatemala. (Upper left ) Ornamental facade with masks of Chac, Palace of the Governor. (Upper right ) Corbeled arch, illustrating the mass of masonry required in the roof, Palace of the Governor. (Above) The Dove-Cotes Quadrangle, North Temple. (Photographs courtesy of Ken Kirkwood.)

Occasionally Mayan pyramids were also used for burial. At the Temple of the Inscriptions at Palenque a burial chamber was constructed under the pyramid with a stairway leading to the temple above (see Fig. 15-8). Within the chamber a sarcophagus with a sculptured lid enclosed the burial of a priest in costume wearing a mosaic jade mask.

Architecture in central Mexico featured a style of pyramid facade best typified at Teotihuacan but present over much of highland Mesoamerica. Termed the Talud-Tablero style, it consists of a stepped temple platform. The steps are made up of a sloping riser surmounted by a vertical riser with a rectangular recess (see Fig. 15-8). The center front of the pyramid featured a stairway flanked with steeply sloping abutments. This is the architectural style so common at Monte Alban and other central Mexican centers. Decorative elements at Teotihuacan feature carved stone heads of the feathered serpent and various deities, set into these wall recesses. Other elements were polychrome wall murals which have been found not only on ceremonial structures but also in the residential blocks.

ART

Mayan art was truly Classic in the sense that it was omnipresent. The media used include wall murals within tombs and temples, bas-relief carving in stone, modeled pottery, mosaic stone plaques, mosaic stone friezes on buildings, polychrome painted pottery, and painted books in hieroglyphs, called codices.

Decorative features of Mayan art include the elaborate costumes of jaguar skins, feathers, and jade ornaments worn by the priests; depicted were rulers, soldiers, war captives, and occasionally women. The art style is curvilinear and flowing, and portrays zoomorphs, plants, and water elements intertwined with the human figures and deities (Fig. 15-10). Other elements include monster figures and monster masks. Priests are shown with the characteristic sloping profile from the end of the nose to the top of the head—a profile achieved in real life by head binding with the resultant frontal deformation of the skull. The hieroglyphs were also highly artistic. In pottery the decorative motifs were similar to the wall panels. Favorite subjects were monkeys, serpents, jaguars, humans, birds, and monsters. Bands of glyphs on pottery were used as decorative borders, with some of these being pseudo-glyphs rather than symbolic in meaning. A major feature of pottery and wall mural painting was the portrayal of humans in profile. Scenes from life occur on the two of the best known murals. One features a battle scene and the other a fishing village on the seacoast. Other murals, of which those at Bonampak are best known, illustrate religious ceremonies.

In central Mexico, the Teotihuacan art style is reflected in polychrome tripod cylindrical pottery jars, jar lids painted with a fresco technique, wall murals, some ornamental carving in stone on the pyramid risers, pottery figurines, carved stone masks of humans, and giant, rather stiff human figures

©g?

a

b

c

e