Q> T3 C

7 cn LU

5 ?

— c

o CO QC

2 2 ^ o

CU co

cc

cu «/>

4-1 - l_

wqh)

± E c

D CD CD

OHO

Z_ cn

O

_ CN _J CD _i cn O C O

O

cc

<

o

Q

o

o

Cl

E

o

o

>

o

a

o o

cn ll cd C_C DC

O

CD

-C

O

ID

CD

O

CO

<

c

CD

-Q

3

Q.

X

d

X

LU

o

<

>

-J >

LU LU

2 CC

^ CO CO CD

3 CD co r~

o

DC

m

Q

z

<

H

CO

CO

<

_]

o

D

CO

>

O

CD

>

O

C/5

c

co

Q_

X

LU

C

CD

E

x

LU

CO

LU

<

a

o

<

_J

LU

o

cc

o LU

ix 2

^ w

<8

•^r to co

LO 'sl

o

o

o

o

o

CD

Table captionO

Table captionS Q

o . o

o CN

o

o

CD

Table captiono

Table captionN

Table captionCC

Table captiono

Table captionI

LU ( < Q LU 2 a ... oc n | z LU O —* N | LU H < a LU u i o | z | "d Q < O |

LATE INTE PERU | ll S X | X ^ QC < 7 LU LU — CL | DC DC < o LU X | E- cc |

o o

o o

CO LO

T— CN

Table caption>

Table captiono

Table caption< CO

Table captionQC a

Table captionLU Q

Table captionO LU cc DC LU CL CL

o | O | O | O |

o | O | O | O |

CN | O | O | LO |

'sT | CD | CO | CD |

o

Table captionCO

Table captionCO

Table caption<

Table caption_l

Table captiono

Table captionH

Table captionCO

Table captiono

CO

CO

<

_l

o

Table captionCO

Table captionCO

Table caption<

Table caption_J

Table captiono

Table captionLU

Table captionQC

o

<

X

o

QC

<

Fig. 16-1 Chart illustrating the correspondence between the Andean chronologies proposed by various researchers and the Mesoamerican sequence. (Modified from Willey 1971 :Fig. 3-6.)

direct historical contacts between Mesoamerican and Andean area cannot be ignored. On the other hand positive proof that such contacts occurred is lacking.

A basic integrative factor present in Andean archaeology is the feature termed Horizon style. Horizon styles are decorative elements which occur together on a variety of media, such as pottery, stone sculpture, weaving, bone carving, and metalwork. A further feature of the styles which makes them of incalculable archaeological value is the fact that these styles are noted for their rapid spread and their brief duration in time. The Horizon styles therefore are useful as chronological markers. They serve to correlate local archaeological sequences one with the other. Through time from early to late, the major Horizon styles are Chavin, White on Red, Negative Painted, TiahuanacoHuari, Interlocking, and Inca (see Fig. 16-1). In brief, Horizon styles are distinctive in character, widespread geographically, and of brief duration. They further serve to provide Andean archaeology with a portion of its unique quality.

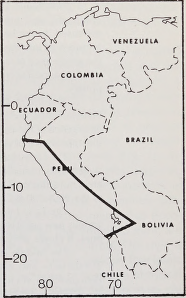

The Andean region is dominated by the Andean Mountain chain rising to 20,000 feet near the equator and diminishing in elevation both to the north and the south. The central region within which most of Andean culture developed includes Peru and portions of Ecuador and Bolivia. This area may be subdivided into six major regions (Fig. 16-2) termed the North, Central, and Southern Highlands and the North, Central, and South Coasts. The highlands include the mountains, high plateaus, and mountain valleys primarily at elevations of 9000 feet or above. The climate is equitable with adequate rainfall in the lower portions. The climate changes to a cold steppe regime in elevations of 11,000-14,000 feet; higher still lie alpine tundra and snowfields. The coastal region is a desert. Rainfall occurs inland in the mountains and returns to the sea by means of a series of 40 or more short, steep, parallel river valleys (Fig. 16-2). The combination of no rain on the coast and the availability of surface water only in the valleys early led to dependence on irrigation. A further bonus is the preservation of perishable materials. The coastal aridity permits the recovery, through archaeological methods, of as complete a record of prehistoric life style as found anywhere in the world. Only Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the American Southwest have similar optimum conditions for preservation coupled with an outstanding culture.

Our discussion of Andean culture history will follow the sequence of periods outlined by Willey (1971:86). His first five Preceramic periods have already been summarized previously. We begin our coverage with the Preceramic Period VI findings at Huaca Prieta and other coastal shell middens and continue through the Inca Empire. A number of authors have reviewed the Andean evidence and subdivided it into major periods. Figure 1 6-1 presents a resume of these classifications which should aid in your understanding of the terms utilized by the various authors.

The periods have been defined by Willey (1971:86) as follows:

* z

FAR

NORTH

Fig. 16-2 The regions of ancient Peru. The map shows coastal and highland subareas, river valleys of the coast, some modern cities, and in the highlands certain archaeological sites. Inset shows the area within its South American setting. (Willey 1971 :Fig. 3-1.)

Preceramic Period VI (2500-1800 B.C.). On the coast this period saw the continuity and enrichment of the Pacific Littoral tradition cultures. Populations increased. In the last centuries of the period the Pacific Littoral tradition began to be transformed into the Peruvian tradition. This transformation or transition was marked by the appearance of large habitation sites, sizable public or ceremonial constructions, and the first appearance of maize cultivation. The period closes with the appearance of pottery.

The Initial Period (1800-900 B.C.). This is the first ceramic period in the Peruvian area archaeological sequence. It is also here considered as marking the emergence of the Peruvian cultural tradition. As has already been noted, it begins with the appearance of pottery. It closes with the first appearances of the Chavin art style.

The Early Horizon (900-200 B.C.). The Early Horizon is the period of the Chavin style and its immediate derivatives. The Chavin style is not represented in all parts of the area, but cultures in subareas and regions where the style is not present may be assigned to the 900-200 B.C. period by cross dating.

The Early Intermediate Period (200 B.C.-A.D. 600). This period opens with the various new subareal ceramic and art styles that replace Chavin and Chavin-influenced ones. It closes with the appearance of the Tiahuanaco and Huari horizon styles.

The Middle Horizon (A.D. 600-1000). The Middle Horizon is the time of the Tiahuanaco- and Huari-derived styles and their propagation throughout most of the Peruvian area. It closes with the emergence, once more, of subareal styles.

The Late Intermediate Period (A.D. 1000-1476). This period, intermediate between the Middle and Late Horizons, is characterized by a series of late ceramic and art styles—and by a series of corresponding late states or kingdoms.

The Late Horizon (A.D. 1476-1534). The Late Horizon begins with the expansion of the Inca style and culture—and with the expansion of Inca militarism and the Inca state—in the late fifteenth century. It closes with the downfall of this empire and the ascendancy of the Spanish conquerors under Pizarro.

The extremely brief resume, period by period, taken from Willey's work permits us to proceed in much the same manner as we did in the preceding chapter. Our concern is to present a synthesis of the major diagnostic features of each period rather than review the regional sequences in detail. The basic cultural pattern shared by all periods is the Andean Farming Tradition described in detail in Chapter 14. In this chapter we will focus on those elements that are unique to each period. Much of the chronology and understanding of Andean archaeology is based on cemetery excavations. Owing to

the spectacular remains preserved in the cemeteries—ceramics and weaving_

major excavations were carried out early in the twentieth century prior to the advent of modern excavation techniques. While the remains preserved in museums today are spectacular, the information associated with them concerning their age and associations is often less impressive. As a result, reexamination of the regional chronologies is a current focus of interest of archaeologists working in the area. In the absence of firm stratigraphic controls the Horizon styles were utilized as a means of site and regional correlation. In the absence of an independent dating technique such as radiocarbon, the Horizon styles were more or less assumed to appear simultaneously wherever they

occur. The reasoning is circular: the styles are assumed to be contemporaneous, and therefore wherever they occur, the cultural layers containing them are believed to be of equivalent age.

The earliest unique cultural manifestations, the Chavin period occurred within the Early Horizon (900-200 B.C.). The Chavin period (named after the typesite, Chavin de Huantar, in the Northern Highlands) is marked by a Horizon style of the same name (Fig. 16-3). In the highlands the Horizon style is present in stone sculpture and other media. On the coast it is present in pottery as well as weaving and metalwork. The style consists of abstract curvilinear representations of a feline or anthropomorphized feline. The single diagnostic feature uniformly present is overlapping canine teeth (Fig. 16-3). Other elements of the style include men, demons, jaguars, eagles, serpents, caimen, and other beasts (Willey 1971:116). The style further features eyes in which the pupils are located at the top of the orbit. The style is symmetrically balanced with numerous repeated elements that are clearly intended as decorative rather than representational. A stylistic analogy that comes to mind are the Buddhas of North India and adjacent China with many arms. The style is contemporaneous with the Olmec culture of the Mesoamerican Preclassic which featured the jaguar mouth art motif. It is tempting to suggest a historical connection on this basis but in fact the similarities between the two styles are more general than specific.

An even more suggestive correlation with Mesoamerica may be made with the carved vertical stone slabs set around the temple at Cerro Sechin in the Casma Valley, northern Peru (Fig. 16-4). The age of the site is uncertain but it is assigned by Willey (1 971:11 2) to the preChavin Initial period. At Cerro Sechin these slabs have been deeply carved with individual human figures in profile. The similarities of these figures to the Danzantes of Monte Alban, Oaxaca, which are of similar age, is indeed striking. Such carved slabs are rare in both Mesoamerica and the Andean area. The Sechin style features warriors or dignitaries carrying maces, seminude or dismembered men, and geometric elements (Willey 1971:112).

Bennett and Bird (1964) have given the term cultist to the Chavin period, for they infer that the art style was associated with the peaceful dissemination of a religious cult which became nearly pan-Andean in scope. The period is marked by a rather sudden flowering of culture. The crafts include outstanding pottery, weaving, and even metalworking. There is evidence in the refuse deposits and cemeteries of a population increase. The appearance of temples signifies a formalized religion as well as a social organization capable of scheduling the construction of public buildings. The appearance of the art style was sudden, without obvious antecedents, unless it may be traced to Cerro Sechin. The style was superimposed upon a number of local cultures, each of which was evolving toward similar cultural goals sharing the common Andean Farming Tradition. Focations of sites at this time in places later abandoned, because they were too swampy or too arid, implies that agricultural techniques were as yet imperfectly developed.

Fig. 16 —3 TheChavin Horizon style in different media: a. Lanzon in the temple interior; b. carving on Raimondi stone, Chavin de Huantar; c. Paracas vessel. (Willey 1971:Figs. 3-38, 3-39, 3-40.)

Fig. 16-4 Major stylistic elements from Cerro Sechin: a. the temple of Sechin, Casma Valley showing the placement of the standing figures; b. details of individual figures from Sechin. (Willey 1971:Figs. 3-30 and 3-31 [redrawn from Tello 1956].)

Cultural Data Revealed by Archaeology

436

In his discussion of cultural innovations, Willey (1970:1 15) is impressed with the developments during the Initial period (1800-900 B.C.). He cites the appearance of plant cultivation, increase in the number and the size of sites, florescence in crafts, and ceremonial structures. However he is unwilling to assert that all these developments were the logical outgrowth of agriculture. He points out that sedentism and population increase first were initiated by the coastal fishing and shellfish-gathering peoples. Thus there was already a social tradition of communal living in effect prior to the development of agriculture. Food debris from Chavin sites, especially the coastal middens, reveal reliance on seafoods as well as the peanut, warty squash, and avocados. There is a strong possibility that the dog was domesticated and the llama kept.

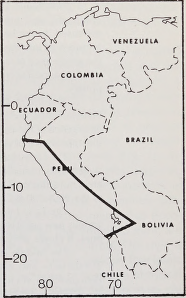

In architecture the most outstanding example is the site of Chavin de Huantar. At an elevation of 10,000 feet in the Northern Highlands of Peru, the Chavin ceremonial complex covers an area 210-meters square. The site constructions consist of a series of rectangular platform mounds with remains of rectangular buildings on top (Fig. 16-5). The platforms contain within them stone-slab-lined galleries and rectangular rooms on three levels connected by stairways and inclines. Interior ventilator shafts provide air to underground galleries and rooms. The exterior facing stones were well cut pieces of granite. Also attached to the platform exterior was a set of human and animal heads sculptured in the round and tenoned into the wall. Other stone sculptures at the site include a cornice carved with figures in relief, carved stone slabs set into the exterior walls, lintels, and columns. Set within one of the galleries inside the platform is the Great Image or Lanzon (see Fig. 16-3), a carved stone slab of prism form. It is carved in bas-relief in the form of an anthropomorphic figure with the Chavin-style fangs, hair represented by snakes, ornaments in the ears, and a necklace as well as a girdle of combined serpent-jaguar faces. The Great Image is presumed to have represented a supreme deity placed in a setting deliberately calculated to inspire awe.

The Chavin style changes through time, with the Great Image being an early more representational figure. The Raimondi Stone (see Fig. 16-3) is typical of the later more abstract style. According to John Rowe, Chavin de Huantar included in addition to the ceremonial center an associated residential area plus several nearby villages. Presumably these villages shared in the maintenance and use of the ceremonial center. The pottery is similar to that of the North Coast.

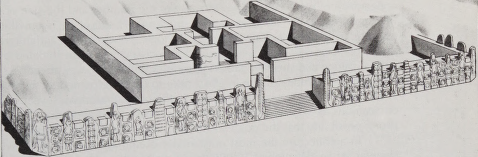

The best known Chavin period pottery is that from the North Coast Cupisnique culture. Typically the pottery is black to brown and highly polished. It features the unique Peruvian vessel form, the stirrup spouted vessel (Fig. 16-6, Nos. 44 and 27), so typical from this period and throughout the entire Peruvian ceramic tradition. Cupisnique pottery is famous for its realistic modeling of plants, animals, humans, and buildings. This tradition of realism in pottery continued throughout the Peruvian cultural sequence, providing us with a wealth of information about their prehistoric life style. Cupisnique

Fig. 16-5 Chavin de Huantar, type site of the Chavin Horizon, a. Plan. (Willey 1971:Fig. 3-36.) fa. View of southeast corner of Chavin Temple, Peru. (Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History.)

NORTH | FAR NORTH | NORTH | CENTRAL | SOUTH | SOUTH |

HIGHLANDS | COAST | COAST | COAST | COAST | HIGHLANDS |

INCA

HORIZON

LATE

PERIOD

WARI

HORIZON

EARLY

PERIOD

CHAVIN

HORIZON

Inca-Cajamarca

Tallan

Inca-Chimu Inca-Pachacamac

735 734 745 755

Table captionIca-lnca

Table captionImperial Inca

704

Cajamarca

Lambayeque Chimu

Chancay

lea

Selda

583 | 608 | 647 | 662 | 686 | 552 |

Wari-Recuay | Wari Lambayeque | North Coast Wari | Huara | South Coast Wari | Wari |

225 510 578 560

523

507

Recuay

Vicus Negative

Mochica

Early Lima

Nazca

Tiahuanaco

220

283 553 426 544

Chavin

22

322

Paracas

Chavinoid Chavinoid

Chongoyape

Cupisnique Ancon

■■

Fig. 16-6 Representative Peruvian ceramic styles by time period. (Sawyer 1968:Terminal Plate.)

pottery is common and usually intact, for vessels were placed in graves as burial offerings. Other decorative techniques include the use of zoned decoration, incising, punctations, and other surface manipulations.

The coast sites also possess temples, of lesser size than Chavin de Huantar but nonetheless impressive. As their major building material they used adobe, made into bricks of conical form. Typical platforms were up to 170 meters square and 30 meters in height. They had as decoration adobe sculptures in Chavin style, some also painted. Domestic architecture was simple with circular and rectangular stone platforms upon which the houses were built. The houses were of adobe with thatch roofs. Metalworking also appears at this time on the North Coast. Manufacturing techniques were limited to soldering, hammering, annealing, and repousse decoration. Items were of thin gold and include crowns, ornaments, ear spools, tweezers, and pins found as grave offerings. The repousse decoration is clearly in the Chavin style.

Chavin influence is seen elsewhere, including the Paracas pottery of the South Coast. The excellently made Paracas wares also include evidence of a non-Chavin tradition. Important ceramic traits are the double spout and bridge bottle (Fig. 1 6-6, No. 322), red slipped decoration, negative painting, whistling bottles, and an emphasis on polychrome painted decoration. Paracas burials include excellent examples of weaving. The painted pottery designs and those of the textiles are similar.

In textiles, the spindle whorl and heddle loom first appear. All weaving was in cotton and included plain weave tapestries, weft stripes, fringes, tassels, and embroidery. Clothing included belts, breechclouts, a head cloth, and featured body painting as well as the wearing of rings, bracelets, ear plugs, and necklaces of bone, turquoise, lapis lazuli, shell, gold, and iron pyrites. Personal beauty was also enhanced by artificial skull deformation.

In review we may categorize Chavin culture as based upon, but not originating, a settled farming way of life. The presence of separate identifiable cultural patterns such as the Paracas pottery is indicative of local autonomy. The Chavin religion, about which we know little, was the only unifying element in the Andean area and its influence was limited to the far North Coast, Southern Highlands, and South Coast. The absence of fortifications implies a peaceful spread of a religious cult based upon worship of an anthropomorphized feline deity. There was no overall political unity and the social organization consisted of family units organized into small villages. The major integrative force in the society was the religion.

THE EARLY INTERMEDIATE PERIOD

In the period 200 B.C.-A.D. 600, within the Andean area we have the development of a series of cultures noted for their originality and regionalistic almost nationalistic, focus. This is the period within which Bennett and Bird (1964) perceive two levels: an early period termed "Experimenter" followed

by a truly Classic manifestation termed “Mastercraftsmen." According to Bennett and Bird it was during the Experimenter period that perfection was acquired in crafts, building, and agricultural methods. Perhaps the deliberate intention to “experiment,” they imply, is overstated; nonetheless this is the time of achievement of control of the environment through irrigation farming. The period was marked by two Horizon styles in pottery: the White on Red and Negative Painted. The Mastercraftsmen, by definition, excelled in crafts and experienced a cultural florescence comparable to the Mesoamerican Classic. Willey (1971:131) prefers to lump these entities into one larger grouping, the “Early Intermediate period," the basic qualities of which he identifies as: the formation of separate states or kingdoms, achievement of a population maximum, regionalized art styles, great valley irrigation systems, the first appearance of interregional warfare, intensive craft specialization, marked distinctions in social class, and finally the appearance of true cities, those communities in excess of 5000 population.

The White on Red and Negative Painted Horizon Styles

The Salinar and Gallinazo pottery styles, which feature the White on Red Horizon on the North Coast, continue the previous incised decoration which often outlines the white painted areas. Applique is also used. The Chavin motif is no longer present; instead designs are simple geometric lines and dots. Life modeling continues, and two new vessel forms are introduced: the handle and spout bottle and the figure-handle and spout vessel. Stirrup spout vessels continue in vogue.

Gallinaz.o pottery has some elements of the White on Red style but more commonly features the Negative Painted style (see Fig. 16-6, No. 175). The latter utilizes a resist-dye painting in which a dull black paint contrasts with the lighter base color of the vessel. Modeling is even more common than in the Salinar pottery. Inasmuch as Gallinazo cultural levels are strat igra ph ica 11 y above those of the Salinar culture, it is apparent that the change from the White on Red Horizon to the Negative Painted Horizon also is indicative of a chronological difference between the two styles. Salinar house types continued to be built on platform mounds or terraces with the house walls of conical adobes. Some rooms were agglutinated into small compounds. Small flattopped platform mounds scattered throughout the valley probably served as local worship centers. On the tops of nearby hills, walled fortifications represent the earliest evidence of warfare recorded in ancient Peru.

The main site at Gallinazo is considerably larger than previous communities. The total site area ranges from 2 to 6 square kilometers depending upon one's definition of how concentrated the population must be to be included. The population is estimated at 5000 to 10,000 persons, living in clusters of adobe apartments, although Wendell Bennett, the excavator, estimated that 20,000 rooms occur within the area adjacent to the ceremonial center. The

latter is dominated by a pyramid 25 meters in height associated with smaller pyramids, platforms, and a walled courtyard. Probably Gallinazo served as the capital of its valley, the Viru, with numerous other small settlements within the valley being occupied simultaneously. The Salinar-Gallinazo sequence is the cultural antecedent of the great Mochica civilization of the North Coast, one of the most outstanding cultures ever to exist in aboriginal America.

Mochica Civilization

We could rely upon Mochica ceramics as the sole means of acquiring information and still be able to reconstruct a creditable version of their life style. The modeled ceramics are so realistic and portray such a wealth of cultural detail, in combination with their realistically painted pottery, that they permit a glimpse into every aspect of ancient Mochica society and life. The Mochica consisted of the inheritors of the North Coast cultural traditions. With their main site at Moche, they expanded beyond their home valley to dominate the North Coast. The emphases in the pottery, mural art, and fortifications imply that this expansion was based upon actual conquest of adjacent valleys.

Architecture featured massive adobe brick ceremonial structures, the most impressive of which, the Huaca del Sol at Moche, is a terraced and truncated pyramid 228 by 136 meters with a maximum height of 41 meters. The Huaca del Sol functioned as a platform for one or more temples while the nearby Huaca de la Luna, a terraced platform abutting a hillside, included

residences, probably of the ruling elite.

The Mochica were highly concerned with personal status. The portraithead vessels record the actual countenances of individuals, each of whom may be identified as to his real life importance because of the geographic distribution of his portrait vessels. In addition, status was further identified by the type of headdress worn. Mochica society was male dominated and militaristic. Other aspects of Mochica society delineated by ceramics include molded animals, plants, demons, house types, and scenes from daily life including sexual practices, hunting, fishing, punishment of prisoners, religious ceremonies, and burial scenes. A further ramification on some painted vessels are scenes of men carrying small bags of beans marked with crosses and dots. It has been suggested that the beans may have served as symbolic ideographs, which if not an actual language, could have served as memory aids in the transmission of messages. ,

The grave offerings provide a wealth of cultural objects. Graves have

been found on top of pyramids, in cemeteries, as well as in locations adjacent to the farmed portions of the valleys. Graves were rectangular pits with the burials in an extended position. Some grave pits were roofed with adobes. The graves feature offerings differing according to the status of the individual buried therein Burial items include the stirrup spouted vessels, ornaments of gold, copper, silver, and inlaid bone. For the first time we have the widespread use of

metal in utilitarian implements as well as in ornaments. Copper was used for axes, spears, helmets, and the points for digging sticks. Metalworking techniques included alloying, casting, and gilding.

With respect to our coverage of the Mochica we cite their achievements as a major regional culture with a strong political organization as well as the infinite variety and accuracy of their modeled ceramics. No other ancient culture surpasses the skill of the Mochica in the manufacture of modeled pottery.

Nazca Culture

The South Coast is known for the development at this time of a culture termed Nazca, after a valley of the same name. A direct outgrowth of the preceding Paracas culture, Nazca culture is world famous for its polychrome painted ceramics. The Nazca ceramic decorations (see Fig. 16-6, No. 426) include designs present earlier on Paracas textiles. New designs include a cat demon, bird, fish, and animal designs. The pottery is noted for its fired pigments, in contrast to the earlier unfired Paracas pigments. Nazca pots are known to have as many as 11 colors, although 4 or 5 are most common—red, black, white, gray, orange, and shades of each. Major vessel forms are the double spouted bottle with bridge between the spouts and open bowls. The design style of the pottery shares many features with the textiles of the famed Paracas Necropolis mummy bundles (Fig. 16-7). The textiles, which were specially manufactured to be used as mummy wrappings, feature a wide variety of weaves including brocade, double cloth, tapestry, gauze, lace, and weft stripe. These textiles are among the highest quality ever manufactured in the world at any time period. Woven of llama wool and cotton, the textiles feature a background color of black, red, or green with embroidered designs in the same elements as the pottery. The weaving is further enhanced by the wide range of dyes used; 190 shades or hues are known.

Architecture and settlement patterns of the South Coast are less well known, owing to the focus of the excavators on the recovery of burials. Large towns or cities did exist at this time on the South Coast. For example at Cahuachi, in the Nazca Valley, a platform was surmounted with a temple of wedge-shaped adobes. Nearby is a ridge covered with walled courts and rooms. Perhaps the best known Nazca features are the strange patterns or drawings on the ground made by removing stones from the surface. The patterns so made are thought to be of Nazca origin, since they are of design elements common to Nazca ceramics and textiles. The designs include primarily geometric elements and animal figures. Their abstract design and large size, necessitating an aerial vantage point to best perceive them in entirety, have led recent authors to ascribe to them mystical meanings. For example Von Dani

ken in his book and movie, Chariots of the Cods, claims they are the work of extraterrestrial beings.

With our discussion of Nazca culture we bring to a close our review of

Andean Civilization

Figure 16-7 Paracas textiles, beautifully preserved and beautifully woven. Up to 190 different hues are known from these textiles. (Hester photograph, courtesy the lea Museum.)

the Early Intermediate period. However, we have not mentioned simultaneous developments in the Andean highlands. In the highlands we had the establishment of centers during this time period at Huari, Pucara, and Tiahuanaco. These came to dominate Andean civilization in the next major period, the

Middle Horizon.

A summary of the Early Intermediate period would emphasize the development of population centers (if not actual urbanism), the rise of military power, the development of regionally oriented city-states, and a wealth of cultural detail only achieved by true civilization. The regionalism of the design styles and media emphasized is self-evident proof of the absence of any overall political or religious integration.

THE MIDDLE HORIZON (A.D. 600-1000)

The Middle Horizon marks a turning point in Andean archaeology. No longer were the regional cultures content to remain within their own valleys, developing their own regional style in crafts, practicing their own religion, and largely

ignoring the endeavors of the regional cultures in the nearby valleys. In this period there developed for the first time an attempt at imperialism. Two cultural centers—Tiahuanaco, in the Southern Highlands at the southern end of Lake Titicaca (see Fig. 16-2), and Huari in the Central Highlands—extended their cultural influence outward by colonization and conquest. Bennett and Bird (1964) term the period expansionist, which is certainly an appropriate term. If our archaeological knowledge was more complete we could identify in this period antecedents of the later Inca expansion. The period may be described as evidencing a concern for the manipulation of man-hour units and political organization of peoples. The major known entity of this period is Tiahuanaco culture largely because of the spectacular site of the same name. Recent research suggests that Huari was of nearly equal importance but it is as yet less well known.

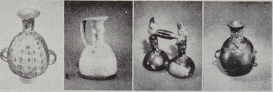

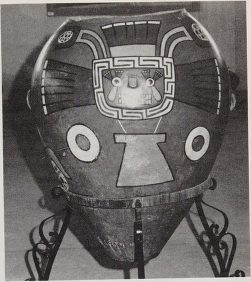

Tiahuanaco

Tiahuanaco is manifest by a major ceremonial center and a Horizon style of the same name. The art style is primarily represented in stone carving, architecture, and ceramics. In ceramics the style exhibits polychrome painting in white, black, and red (Fig. 16-8). Ceramics are highly polished with a red slip and designs outlined in black. The basic feature of the style is a standing anthropomorphic deity facing forward and clasping a staff in each hand. The overlapping canine teeth recur as a motif. Other motifs include heads of birds and animals, running figures in profile wearing a cape and bird mask, repeated profile figures of pumas and condors, and repeated geometric designs, circles, dots, and crosses. The design style is frequently stylized to the point that the deity figure is represented only by the face, with the body made up of geometric elements.

The Tiahuanaco style spread as a complex, thus implying concommitant political and military unity. Early in the period the Tiahuanaco style was disseminated northward to Huari which then began its own consolidation and expansion. The Tiahuanaco style and empire is therefore primarily limited to the southern Andes, including southern Bolivia, the south coast of Peru, and the Atacama desert region of northern Chile.

The site of Tiahuanaco consists of a major ceremonial center built at an elevation of 14,000 feet. Because this elevation is too high for most crops, except quinoa, potatoes, and oca, there was considerable reliance on herding. The environmentally limited economy probably was responsible for the site construction pattern and use. The site was probably not a residential center for the populace. Archaeologists believe the site was constructed at intervals, perhaps during religious pilgrimages, at which time the regional population accumulated materials used during the rest of the year by a small group of skilled construction workers. The site was never finished. The building of sections at intervals would explain the presence of structural units which are internally organized but are not arranged into an overall site plan.

Fig. 16-8 Ceramic vessel typical of the Tiahuanaco Horizon style. (Hester photograph, courtesy the lea Museum.)

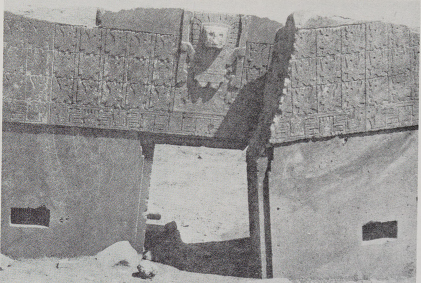

There are four major structural units and several smaller ones. The largest consists of a natural mound made into a pyramid 210 meters square and 1 5 meters in height, on top of which are house foundations. Also associated is a water reservoir. The unit may also have served as a fortress. Another unit features a stone-faced earthen platform 135 by 130 meters with an inner courtyard. Associated are stone statues and a monolithic gateway. The other structural units are similar but smaller. Carving in the round is suggested, but actually the technique employed consists of bas-relief carving on four sides on slabs weighing up to 100 tons. The monolithic gateways are most impressive (Fig. 16-9). These were made by carving a doorway through giant stone slabs. The gateways are decorated by friezes of bas-relief carving in the Tiahuanaco style. The friezes are carved with stiff human figures, pumas, and condors in profile. The largest gateway, called the Gateway of the Sun, has located above the doorway a deity termed the Gateway God, which faces frontward clasping a staff in each hand. He is a variant of the anthropomorphic deity with a

headdress of snakes and a jaguar-style mouth. .

Our knowledge of Tiahuanaco is limited because of the lack of major excavations. We do know something of the architectural stoneworking, since it is exposed Stone for sculptures and construction was imported from quarries 5 kilometers distant. Building blocks were fitted together by cutting notches or

' fa!.

Fig. 16-9 Monolith gateway at Tiahuanaco. (Willey 1971:Fig. 3-90.)

forms include flaring sided goblets, open bowls, and bowls with annular bases. Although up to eight colors of paint were used, most pottery is black white and red.

In the highlands, sites of Tiahuanaco culture are represented by cemeteries, stone building units, and stone sculpture. Sites on the coast are primarily represented by cemeteries. It is from the coast, where preservation is so good, that we have most of our evidence of the textiles. Tiahuanaco textiles are well made, especially tapestries; the decoration includes use of the Tiahuanaco Horizon style.

Several styles of burial were practiced. On the Central Coast the burials are in pits; mummies are wrapped in special burial garments with an attached mask of clay, metal, or wood. The South Coast burials are in large pottery urns. In the highlands burials were placed in boxes lined with stone slabs.

The Tiahuanaco cultural expansion shows evidence of not being well organized or enduring. In terms of cultural dynamics the period seems to have been confused, with earlier buildings on the coast being reused and some valley bottom irrigation systems in temporary disuse. At the end of the period there is evidence of reorganization with some coastal sites featuring villages made up of clusters of rectangular enclosures. Late in the period the Tiahuanaco Horizon style was replaced by local styles featuring the geometric designs of the Black, White, and Red Horizon.

Andean Civilization