MR. DIAW HAS ME down as an official troublemaker now. That’s jacked up. And G-ma’s at the school three afternoons a week! Man, this is not going to be easy. If she hears about my detention, I’m done like Shaq’s short rap career.

I guess I could try to explain. But look how that went with Mrs. Freeman and Mr. Diaw. Maybe G-ma would get it…or maybe she’d just come down on me even harder than ever. I’ll be getting called Grandma’s Boy for so long, they’ll have to start calling me Grandma’s Really Old Man.

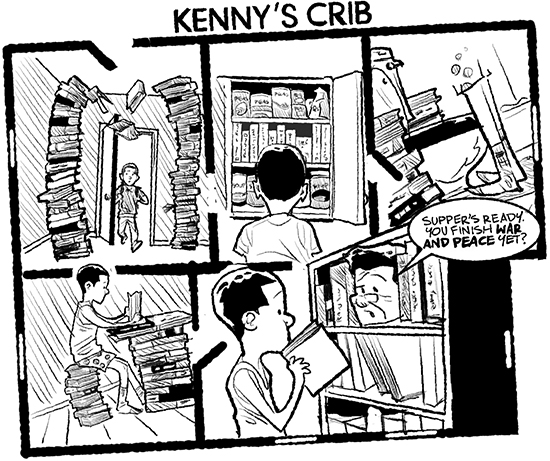

When I get home, I go straight to my room and hide my head inside a book. It’s not that hard to do. Our apartment’s like a library. G-ma’s got bookshelves in every room in the house. Even the bathroom—no kidding.

At home, I have to read every day. That’s the rule. Even Saturday and Sunday. Even Easter and Thanksgiving. Right now, I’m holding my copy of Bud, Not Buddy in front of me like some kind of shield. We’re reading it for English, which I figure will make G-ma happy. She thinks it’s one of the best books ever. In fact, I already read it last year.

“Kenneth!” G-ma says, and I almost jump out of my skin. “I called your name three times. Are you reading, or daydreaming?”

“Reading,” I say.

“Just so you know, we’re eating early tonight. Then we’ve got a neighborhood meeting,” she tells me.

“Can’t I stay home? Please?” I ask, even though I know the answer. I always have to go to these neighborhood meetings of hers. It’s a whole lot of yakkety-yak most of the time.

“No, sir,” she tells me. “In fact, I want you to say a few words tonight.”

“What?” I say. “What kind of words?”

“About what it’s like to go to that run-down school of yours. That’s what the meeting’s about.”

G-ma’s all about words. She likes books. She likes conversation. And as you can tell, she likes talking. A lot.

As for me, I’m all about saying as little as possible right now.

“I don’t know, G-ma,” I tell her. “You really think people care about what I have to say?”

The way she looks at me, I can feel the lecture coming on like a thunderstorm.

“Kenneth Louis Wright,” she says. “Don’t you think a decent education is worth speaking up for?”

“Well, yeah,” I say. “But—”

“Words are our weapons against what’s wrong in the world.” She keeps going. “Why do you suppose Mr. Christopher Paul Curtis bothered to write that book in your hand?”

“To tell a story?” I say.

“Yes. But why?” she says.

I think about it for a second. “Because he had something to say.”

Now G-ma smiles like I made her proud. It’s kind of the best feeling in the world. But it doesn’t last long, because then I remember that I’m also a low-down, no-good lying dog of a grandson.

“Tonight I want you to tell your story,” G-ma says. “Everyone has one. And every story’s valuable. You’re old enough to understand that now.”

I want to say, I’m also old enough to stay home alone. But instead, I quit while I’m ahead. Or at least, while I’m still alive.

“What time’s the meeting?” I say.