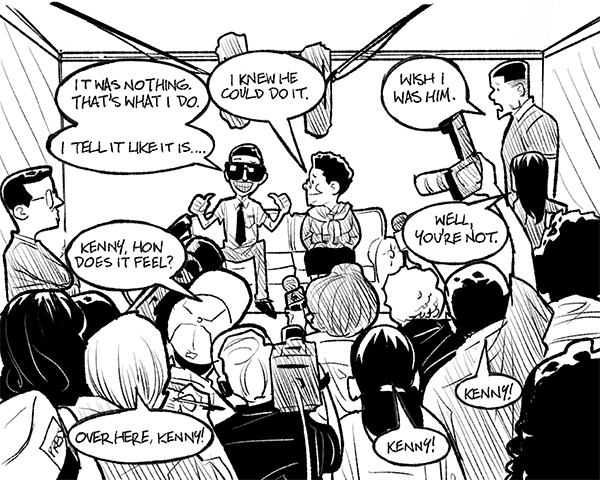

I’M ON TV that night. There’s a whole story about the march on the news, and they even show me talking for about ten seconds. I’m famous! It’s awesome…

…for about ten seconds. Then it’s time for G-ma and me to have a big talk.

Actually, I do most of the talking. I tell her about everything—from that first detention, to that car ride with Nicky, to the real reason Ray-Ray and I weren’t playing chess yesterday. G-ma doesn’t like it, but she listens long enough to let me get through it.

“I’m really sorry, G-ma,” I tell her. “I lied way too much.”

“One lie is too many,” she says, and I guess I can’t argue with that.

“I’ll take whatever punishment you have to give me,” I say. “But there’s something else I want to say first.”

“Haven’t you said enough?” she asks me.

Still, I keep going. “You need to figure out that I’m not a little kid anymore. I’m eleven years old—”

“And eight months, and twenty-two days,” she says. “What does that have to do with lying, Kenneth?”

“Part of this—a lot of it, actually—has to do with what they call me at school,” I tell her. I know she’s not going to like this, but I can’t turn back now. “Grandma’s Boy,” I say.

“What’s wrong with that?” she says. She even looks kind of hurt. “Why would they think that’s something to be ashamed of?”

“See? This is part of the problem,” I tell her. “I mean…I like being your grandson. And I am Grandma’s Boy, here at home. But out there? At school? I need to start growing up. And you need to understand that.”

“You’re still a child, Kenneth,” she says. “Not a grown-up. Not yet.”

“But I will be someday,” I say. “And I am the man of this house.”

I stop there because it’s making me think about my dad, and how I’ll have to grow up the rest of the way without him.

But hey, if I’m lucky—if I’m really, really lucky—then I’ll be a whole lot like him when I get there. As much as I can, anyway. I don’t know if anyone can fill those shoes. But the thing I’m trying to tell G-ma is that I want to try.

I think she gets it, because she’s crying, too. Not a lot. G-ma almost never cries. Still, I can see she’s holding back some tears, trying to be strong for me like she always does.

“Even though you’re the only male in the house, that doesn’t make you the man of the house,” G-ma says.

“Aren’t they the same thing?” I ask. I mean, really, aren’t they?

“You’re going to grow up to be a fine man someday, Kenneth. But take your time. Enjoy being eleven. Enjoy the ins and outs, the ups and downs, and the bumps and bruises you’ll receive becoming a man,” G-ma says in a clear but trembling voice.

“And…there’s one more thing,” I say. “I want to walk to school by myself from now on. Is that okay?”

G-ma puts an arm around me and pulls me in close. She takes a deep breath and says, “All right. I’ll think about that.”

Which is pretty close to a yes, if you know G-ma.

“Cool,” I say.

“Just as soon as you’re un-grounded,” she says. “Maybe after Christmas.”

And I’m like, What? “But I told the truth!” I tell her. “The whole truth!”

“Telling the truth isn’t an extra-credit assignment,” G-ma says. “It’s what grown-ups are supposed to do.”

“But—” I say, before she keeps going.

“Your steps are made of stone, Kenneth,” G-ma says. She turns sideways on the couch now and looks me right in the eye. “Always remember that. Whichever ones you choose to take—that’s it. The truth of those steps stays behind you, hard as rock. Forever. You have to live with them, consequences and all.”

I don’t say anything to that. I know G-ma’s making sense, and I know I’m going to have to be grounded, like it or not. Once she decides something, that’s pretty much it.

But there is one thing she got wrong. My steps aren’t made of stone.

They’re made of steel.