Some General Observations

A FEW GENERAL observations about the psalms are in order before beginning our study. Some of these observations have been alluded to in the preface but need to be developed more clearly. Others provide important groundwork for understanding the context of the biblical psalms. All can provide us depth and nuance in interpreting specific psalms as well as the whole collection and in understanding the lives of faith that both produced and continue to employ these ancient compositions.

Collection and Authorship

AS MENTIONED IN the preface, the composition of the individual psalms covers a period of more than eight hundred years. Add to this the time involved in gathering and shaping the Psalter collection and you have almost a millennium. This in itself is remarkable. Consider the differences that have occurred in English language and culture since the time of Geoffrey Chaucer (600 years) and you have only two-thirds of the time span involved in the creation of the psalms! One has only to read the prologue to Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales to discover a clear example of how much language and culture can change in six centuries.

Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote

The droote of Marche hath perced to the roote

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendred is the flour

Whan Zephyrus eke with his swete breeth

Inspired hath in evry holt and heath

The tendre croppes and the younge sunne

Hath in the Ram his halfe course eronne

And smalle foules maken melodie

That slepen all the nicht with open eye

So priketh him nature in her courages

Than longen folkes to goon pilgrimages

And palmeres for to seken stranges strandes

To ferne halwes couth in sondry landes

And specially from evry shires end

Of England to Canterbury they wende

The hooly blissful martyr for to seke

That them hath holpen whan that they were sick.

The book of Psalms then represents the end result of a long history of composition, transmission, collection, and arrangement. It contains some of the earliest and some of the latest texts in the Old Testament and is in a sense a microcosm of the whole Old Testament corpus. This is not a book that trickled off the tip of the pen of a single author. It is, like so many of the Old Testament books, a collection of compositions by many different authors in many different times and settings. It even bears within itself evidence of earlier psalms collections. Psalms 3–42 surely represent an earlier collection of Davidic psalms, as their headings attest. Psalms 120–134 all share the common heading “Psalm of Ascent,” probably a much later collection of psalms sung by pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem. The Asaph psalms (50; 73–83) and the psalms of the Sons of Korah (42; 44–49; 84–85; 87–88) probably represent the remains of collections of songs written by these two guilds of temple singers.

At a later date, toward the end of the B.C. period, more and more psalms were assumed to have been written by David. The Greek translation of the Old Testament (the Septuagint, abbreviated LXX) expands Davidic authorship by supplying a number of additional psalm headings in which David is explicitly mentioned. The Qumran Psalms Scroll, treasured and preserved by the sectarian community who lived at a desert commune on the northwest edge of the Dead Sea from the second century B.C. until A.D. 70, “davidizes” the Psalter even further by adding more Davidic headings, new psalms attributed to him, and a prose statement celebrating David as prophet and author of 4,050 psalms and songs. It is little wonder that by the time of the New Testament writings, this growing collection, despite clear reference to other authors throughout, could be referred to as David (Heb. 4:7). Indeed, the Jewish rabbis came ultimately to affirm the Davidic authorship of all the 150 canonical psalms.

This assumption that David composed all the psalms in the book of Psalms remains with us today despite clear evidence for other authors in the psalm headings themselves and the lack of certainty whether these references (where they exist) always indicate authorship. The easy and exhaustive assumption of Davidic authorship can obscure references in some psalms to events or settings long after the death of David and inhibit rather than aid our interpretation of them. Also at risk is our appreciation of the long history of psalm composition that parallels the life of the nation Israel from beginning to end, from monarchy to Exile and beyond.

A VARIETY OF names has been applied to this book, each of which reflects a distinct way of viewing the collection over the ages. One of the earliest titles took its departure from the Davidic character of nearly half of the psalms. As early as the New Testament period, then, it was possible to refer to this collection as “David,” in deference to its primary author. This is not surprising in light of the growing tendency (at Qumran and among the rabbis) to attribute more and more psalms to David. It is, however, not a completely apt title for such a diverse collection, and it is not unexpected that this form of reference did not last, despite the continuing assumption, up to the present, of the Davidic authorship of the psalms.

What this early designation may indicate is the existence of a precanonical form of the book of Psalms that was made up almost entirely of Davidic psalms. The first two books of the Psalter (Pss. 3–72) may well embody this early Davidic collection, the conclusion of which is marked out by a postscript (the only such postscript in the whole Psalter) in 72:20: “This concludes the prayers of David son of Jesse.” While it is true that even these two books are not exclusively Davidic (Book 2 contains one psalm ascribed to Asaph and a series attributed to the Sons of Korah), the collection both begins and ends with Davidic psalms, and the concluding postscript emphasizes the Davidic character of the whole.1

Almost equally contemporary to the Davidic title is the practice of referring to the individual compositions with the general designation “psalms.” This form of designation is also known in the New Testament (Acts 13:33). The term psalm is derived from the Greek psalmos, which was the regular LXX translation for the Hebrew genre term mizmor, which appears frequently in the psalm headings. Mizmor means “a composition/song performed to musical accompaniment”; psalmos is similar in meaning, designating a “song sung to the accompaniment of the harp.” The Hebrew is not as specific as the Greek in describing the nature of the accompanying instrument, nor does it claim to describe all the compositions included in the book of Psalms.

It is from the Greek reference to the individual psalms that the more current title for the collection as the book of Psalms is taken. Despite its longevity, however, this title remains somewhat inadequate as a designation for all the diverse compositions included in the book. It is certainly not clear that all the canonical psalms were originally intended to be accompanied by the harp. The psalm headings offer a large variety of types of compositions and indicate a number of instruments to be employed in accompaniment. Regardless of these deficiencies, the title book of Psalms does have the advantage of being a more inclusive general designation with the weight of extensive historical and traditional usage.

Within the Hebrew Bible, from the earliest period, the common designation for the collection of canonical psalms was tehillim (“praises”). The term is taken from the same root hll, from which the frequent call to praise Yahweh (hallelujah) that punctuates the final third of the Psalter is derived. Once again, however, the term seems inadequate to describe the full range of the contents of the Psalter, since the book is replete with laments, wisdom psalms, historical poems, and other compositions that defy this designation.

It is interesting in light of this Hebrew title that the final third of the book of Psalms is dominated by the appearance of praise and thanksgiving psalms, in strong contrast to the first two-thirds of the book, where lament psalms strongly predominate.2 The decision to characterize the whole collection as “praises” may be influenced by this decisive movement from lament to praise, so clearly illustrated by the final grouping of the Hallelujah Psalms (146–150). While the title does not adequately indicate the nature of all the compositions in the book, it does capture the effect of the theological arrangement of the psalms in the book, which in the final analysis does become a book of praise in full awareness of and in spite of the experience of lament and sorrow in life. This is an important point to which I will return at a later point in a discussion of the shape of the Psalter and its theological import.

So, these different ways of titling the book of Psalms offer us competing ways of understanding the contents of this book. For the Christian Scriptures, the attempt was and is to employ the title “Psalms” in order to provide a more general description of the nature of the psalms that emphasizes their character as songs to be sung. This is hardly surprising in light of the early use of musical versions of the psalms for singing as an important part of Christian worship (cf. Eph. 5:19; Col. 3:16) and the continuation of that practice through the use of metrical psalms throughout the centuries since. In contrast, the Hebrew title (tehillim) highlights the overall effect of the collection with its movement from lament to praise, establishing the confidence and hope that despite the suffering realized in life, Yahweh’s final word is always deliverance and benefit worthy of our most extravagant praise.

As for the use of the title “David” to characterize the whole Psalter, it is true that David assumes an important role in relation to the collection of the psalms. From the significant number of psalms attributed to him (whether in the canonical collection, the LXX, or the Qumran Psalms Scroll), to the editorial shaping of the first two books as the prayers of David (cf. 72:20), to the distribution of Davidic psalms through the whole canonical collection, to the influence of the Davidic covenant on the editorial shaping of the final Psalter, the book of Psalms is in a real sense (without assuming the Davidic authorship of all 150 psalms) the Book of David.

As to the exact referent of the allusion in Hebrews 4:7, my study of the shaping of the final canonical collection (see the essays on “The Shape of the First Three Books” and “The Shape of the Psalter as a Whole” in vol. 2 of this commentary) suggests that the author of Hebrews may have had in mind an earlier form of the book of Psalms complete only through Book 2 (Ps. 72) or Book 3 (Ps. 89), where the Davidic motif is most strongly maintained. The subsequent addition of Books 4 and 5 (perhaps as late as the end of the first century A.D.) would have changed the character of the whole and opened the door to new titles, reflecting alternative ways of understanding the Psalter.

The Historical Use of the Psalms

MOST OFTEN TODAY, when we think of the psalms, we understand them as ancient models of private prayer spoken by individuals to God. The fact that we can still consider all 150 psalms the products of David, regardless of evidence to the contrary, is proof that belief in the private, personal nature of the psalms is still alive today. As the prayers of ancient individuals, the psalms can either be inspiring models that we adapt profitably for our own personal life of prayer, or they can be puzzling or even offensive proclamations from an alien land—difficult if not impossible for us to relate to.

It is true that over the centuries of their use the psalms have been viewed this way and have come to serve fruitfully as models for our own prayer life, and our tendency is to think of the psalms in this way—as if they were simply written by private individuals for use in their personal prayer closets, so to speak. But such a view misunderstands the very public nature of most of these compositions and misses out on a wealth of interpretive detail that can be drawn from their original function and setting.

Origin in Temple Worship

SCHOLARS GENERALLY AGREE today that most of the psalms (some even say all) were composed, not for private prayer, but for public performance in the temple worship of ancient Israel. If this is so, then even the individual psalms were not composed simply for private use but were intended to be presented—performed, if you will—within community worship. Many of the notices in the psalm headings lend support to this view. Some appear to be instructions to the music director (lamnaṣṣeaḥ, “to the director”), describing the type of composition (mizmor, maśkil, tehillah, šir hammaʿalot, etc.), appropriate instrumentation (binginot, “for the strings”; haggittit, “the Gittite harp”), the tune (ʿal ʾayyelet haššahar, “according to the Gazelle of the Dawn”; ʿal yonat-ʾelem-reḥoqim, “according to the Dove of the Distant Terebinth”), and even the musical tuning to be followed (ʿal haššeminit, “according to the eighth”). It is clear from these notices that many of the psalms were traditionally used as performance pieces during the worship services of ancient Israel.

Some of the psalm headings even include mention of specific worship settings. For instance, the heading of Psalm 100 contains the phrase “For the todah [thanksgiving offering].” The best explanation seems to be that this psalm was composed to accompany the presentation of the todah or thanksgiving offering celebrating divine deliverance from some distress. A similar reference is found in Psalms 38 and 70: “For the hazkir [memorial offering].” Following the same pattern, Psalm 30 was performed “At the Dedication of the House,” possibly a reference to the dedication of the temple of Solomon or some later restoration of that edifice after the Exile. Psalm 92 declares itself “A psalm. A song. For the Sabbath day.”

Another support for this idea of public use of the psalms in worship is the mention in the headings of twenty-four psalms of several guilds of temple singers (Asaph: 50; 73–83; the Sons of Korah: 42; 44–49; 84–85; 87–88; Heman: 88; and Ethan: 89), who are described in the accounts of 1 and 2 Chronicles as part of the official worship structure of the temple from the time of David and Solomon on. The name of another singer known from Chronicles, Jeduthun (cf. 1 Chron. 16:41–42; 2 Chron. 5:12), also appears several times in the psalm headings, but always in connection with another author name (Pss. 39 and 62: “a psalm of David”; 77: “a psalm of Asaph”), so that the significance of the word yedutun in these circumstances must be questioned. The appearance of so many names so clearly associated with the official organization of the musical worship of the Jerusalem temple adds weight to the view that many of the psalms originated as public performance pieces produced by groups of singers with official oversight of the temple service.

Other psalms open windows into Israel’s worship practices within the body of the psalm itself. In Psalm 42, for example, the speaker recalls “how I used to go with the multitude, leading the procession to the house of God, with shouts of joy and thanksgiving among the festive throng” (42:4). A similar procession is described in 68:24–27:

Your procession has come into view, O God,

the procession of my God and King into the sanctuary.

In front are the singers, after them the musicians;

with them are the maidens playing tambourines.

Praise God in the great congregation;

praise the LORD in the assembly of Israel.

There is the little tribe of Benjamin, leading them,

there the great throng of Judah’s princes,

and there the princes of Zebulun and of Naphtali.

Elsewhere the psalmists mention moments of worship as the context of praise, lament, and thanksgiving.

With my mouth I will greatly extol the LORD;

in the great throng I will praise him. (109:30)

I wash my hands in innocence,

and go about your altar, O LORD,

proclaiming aloud your praise

and telling all your wonderful deeds. (26:6–7)

How can I repay the LORD

for all his goodness to me?

I will lift up the cup of salvation

and call on the name of the LORD.

I will fulfill my vows to the LORD

in the presence of all his people. . . .

I will sacrifice a thank offering to you

and call on the name of the LORD.

I will fulfill my vows to the LORD

in the presence of all his people. (116:12–14, 17–18)

Add to these explicit references the abundant indications of worship performance within the text of the psalms themselves and you have clear evidence of the use of the psalms in the temple worship system. The antiphonal structure of Psalm 136 is best explained by the liturgical demands of worship, where two choirs respond to each other, or leader and congregation answer back and forth. Similarly, in 24:7–10, we hear the voices of worshipers inside the temple compound query the approaching throng that demands entrance:

Lift up your heads, O you gates;

be lifted up, you ancient doors,

that the King of glory may come in.

Who is this King of glory?

The LORD strong and mighty,

the LORD mighty in battle.

Lift up your heads, O you gates;

lift them up, you ancient doors,

that the King of glory may come in.

Who is he, this King of glory?

The LORD Almighty—

he is the King of glory.

All these indications of the liturgical use of the psalms make it difficult to deny that many (if not all) of the psalms originated and enjoyed a long history in the temple worship of ancient Israel. Despite our present tendency to regard the psalms of the canonical collection as private prayers written by individuals in response to personal circumstances, the singing of the psalms through the centuries has continued to reflect the more communal nature of these songs as worship hymns.

From Public Performance to Private Piety

HOW IS IT, then, that these performance pieces intended for presentation in communal worship came to be regarded as private prayers and were used instead as models for the personal prayers of the faithful? Some particularly significant national event would seem to be required to account for such a distinctive shift in use of the psalms—some crucial experience that created a change of national perspective so strong that the original connection of the psalms with temple worship might be forgotten, or at least obscured.

Two such events come readily to mind and have been frequently offered as the occasion behind this change in the understanding and use of the psalms. Both events involve the destruction of the Jerusalem temple and the loss of the temple worship system in which the psalms figured so prominently. Both required a process of national reidentification in response to extreme cultural dislocation. The two events are separated by some 650 years and herald the two major transitional periods in the development of Judaism out of ancient Israelite faith and practice.

The end of the first temple. The first of these two events is the destruction of the first temple (known as the temple of Solomon) at the hands of the invading Babylonian army in 586 B.C. and the subsequent national dislocation of the nation of Israel in the Exile. The temple was razed to the ground, temple worship no longer existed, and the vast majority of Israelite population was transported out of their native land to live out their days in the alien environment of the far reaches of the Babylonian Empire. The kingdom to which they had claimed citizenship no longer existed.

Their passports cancelled, standing on unfamiliar and hostile ground, forced to take stock of their rather naive earlier faith in Yahweh’s unconditional protective care for his covenant people, exilic Israel underwent a painful reidentification process in order to develop a new understanding of what it meant to be a faithful follower of Yahweh. The devastating pain of the Exile and its effect on the Israelites and their use of the psalms can be heard clearly in the harsh and grating language of Psalm 137.

By the rivers of Babylon we sat and wept

when we remembered Zion.

There on the poplars

we hung our harps,

for there our captors asked us for songs,

our tormentors demanded songs of joy;

they said, “Sing us one of the songs of Zion!”

How can we sing the songs of the LORD

while in a foreign land? (137:1–4)

Unfortunately, we have little historical material that describes the life of exilic Israelites during this time. Ezra, Nehemiah, Daniel, and Esther offer but tantalizing glimpses of Israel in captivity, practicing their faith in a hostile environment. We do know that most of the Old Testament as we now have it was written or shaped during this period. We can discover traces of the reidentification process that led the exilic Israelites into Judaism in the way the historical books Samuel through Kings interpret the monarchical experience and explain why it came to ruin. We can learn about the issues that concerned the exilic community when we read the prophets, especially their hopes for the future.

We even know that it was during the Exile that the synagogue arose as a local center for Jewish political, social, and religious cohesion. Isolated in the midst of a foreign nation, far from everything familiar and comforting, exilic Jews faced the siren’s call of assimilation to the majority culture and founded the synagogue as a hedge against the loss of their identity—their very soul. It is true that by the time of Jesus in the first century A.D., the synagogue was a well-established institution with regular Sabbath services. But exactly when it began is still something of a mystery, and what its services were like remains a matter of conjecture and debate.

What we do know is that the synagogue became the site for the collection, interpretation, preservation, application, and transmission of the growing biblical corpus. In light of the exilic experience, the Jewish community, gathered around synagogues throughout the world, selected and shaped the holy writings of Hebrew Scripture to help their dispersed nation understand what it meant to be faithful followers of their ancestral God, Yahweh, in their new circumstances.

Among the materials collected, sifted, and preserved as part of this incipient collection of Scripture were most certainly the psalms. When the Jerusalem temple was destroyed in 586 B.C., temple worship—and, by extension, the performance of the psalms—ceased as well. It is in this setting that the first step in the remarkable shift in the way the psalms were perceived and used was taken. It became important to record them, preserve them, and transmit them safe until their use would be restored. If you could no longer sing them in communal worship, you could study them for what Yahweh wished to teach you, and their laments, praises, and thanksgivings served as models of personal piety that remained at the same time poignant reminders of what had been lost and hopeful imagining of what would one day be restored. The early collections in the Psalter (David, Asaph, Sons of Korah) may reflect this initiative to collect and preserve. The notations in the psalm headings reflect similar concern to pass on details of performance to future generations of the faithful.

In other words, in response to the loss of the temple and temple worship the perception of the psalms began to shift from public performance pieces to written Scripture, to be studied for insight into the ongoing life of the exilic Jewish community. While it is likely that the exilic experience began the process of understanding the temple worship psalms as written Scripture, it is less likely that the seventy-year period between the destruction of the first temple by the Babylonians and the restoration of worship in the second temple during the time of Ezra and Nehemiah was sufficient to obliterate completely the memory of the psalms as temple worship songs. It is clear that new, postexilic psalms were added to the preexilic collections, since some have found their way into the canonical Psalter (e.g., Ps. 137). The Ascent Psalms (120–134) are most certainly psalms sung by exilic Jews on pilgrimage to the restored Jerusalem temple. Thus, with the resumption of temple worship, the psalms resumed their place as an important part of the communal worship experience.

So, if the exilic period does not represent the final impetus for the psalms becoming Scripture rather than performance pieces, when did sufficient time exist to allow for the transition? When would the psalms be so removed from communal worship performance that the musical notations and instructions in the psalm headings could become vague and obscure terminology, as they clearly have in the LXX? This leads us to the discussion of the second cataclysmic event that forced a further reidentification process on worldwide Judaism.

The demise of the second temple. As the first event described involves the destruction of the first temple by the Babylonians, so the second event, some 650 years later, was precipitated by the destruction of the second temple (also known as Herod’s temple), this time by the Romans in A.D. 70. As in the first instance, the destruction of the second temple also meant the cessation of temple worship and the use of the psalms in this context. The effects of this second disruption were much more far-reaching than the first. The second temple was built only seventy years after the destruction of the first. From the time of the Roman destruction until the present day, however, there has been no restoration of the temple or temple worship—almost two thousand years later!

The destruction of the second temple and the long-term cessation of the temple worship system confronted worldwide Judaism with another reidentification problem equivalent to that faced in the Exile. Prior to A.D. 70, the Jewish community had retained hopes of reestablishing the national identity they had lost in the sixth century B.C. This dream was fostered by the success of the Maccabees and Hasmoneans in the second and first centuries B.C. and encouraged numerous rebellions against foreign rule by Zealot groups in the first century A.D. It was one such rebellion, beginning about A.D. 67, that occasioned the Roman suppression that resulted in the destruction of the second temple.

Not all parts of the Jewish community agreed that violent overthrow of foreign overlords was the appropriate response. At least one influential member of first century A.D. Judaism, Yoḥanan ben Zakkai, argued forcefully that dedicated piety and pacifistic waiting for divine intervention ought to replace the Zealots’ violent attempts to overthrow Roman rule and to force Yahweh’s hand by their bold action. Yoḥanan refused to participate in the rebellion and withdrew to the Roman occupied coastal town Yavneh. From there he was highly influential in the restructuring of Judaism in the aftermath of the destruction of the second temple. It was also here that the final debates regarding the contents of the last section of the Hebrew Bible, the Writings (of which the Psalms are a part), were carried out in the concluding decades of the first century.

Yoḥanan’s program was simple, but it has provided the defining structure of orthodox Judaism ever since. According to Yoḥanan, faithful followers of Yahweh, wherever they live, are to demonstrate their faith through regular prayer, good deeds, and study of Scripture, while waiting for God to intervene in their behalf, in his own time. These “sacrifices” of pious living form an adequate replacement for the lacking temple worship system until God sees fit to restore the temple. Yoḥanan’s discouraged active rebellion against Rome but encouraged the Jewish community to maintain their distinct identity as a religious minority set apart from majority culture by their dress, customs, and religious practices.

Yoḥanan’s encouragement to pacifist submission to Roman rule was not easy for any of the Jewish community to accept—especially the Zealots. But when the Bar Kokhba rebellion between A.D. 132 and 135 met equally swift retribution from Rome and was mercilessly crushed, the wisdom of Yoḥanan’s teaching sank home at last. Through this change in focus from communal worship to personal piety and public performance in the temple to study and meditation on Scripture, the authority for everyday Jewish life shifted from the priestly celebrants involved in temple worship to the rabbis, learned scholars who immersed themselves in Scripture and thus were best able to interpret its application to the ongoing needs of life.

It is in this environment that the final impetus to reunderstand the psalms as written texts of Scripture to be studied and meditated upon, both as models for personal prayer and as sources of divine guidance for daily living, took place. What had begun in response to the devastations of the Exile was now brought to completion in response to the lasting destruction and reorientation of A.D. 70. From this point on, the psalms, while retaining in their headings memories of their liturgical usage in temple worship, were firmly established and even emphasized as texts to be read and studied as the Word of God to humans.

In my opinion, the canonical arrangement of the book of Psalms preserves clues of these two formative historical events in its shaping. The core of the first three books (Pss. 1–89), with their shared focus on authorship collections, reflects the response to the first cataclysmic event of the Exile. The final two books (Pss. 90–150) and the final shaping of the whole Psalter are a later response to the events occurring toward the end of the first century A.D.

Christian Adoption of the Psalms

UP TO THIS point I have been speaking of the use of the psalms within the Jewish community. With the advent of Christianity in the last half of the first century A.D., Christian use of the psalms shares some similarities with Jewish usage while at the same time exhibiting some distinctives. I have already mentioned that the early Christians were known to sing the psalms as part of their worship (Eph. 5:19; Col. 3:16). This is hardly surprising, given the origin of early Christianity within Judaism and the common practice of Jewish Christians to worship regularly in the synagogue and temple.

Christians also shared with their non-Christian Jewish contemporaries a desire to employ Scripture as a means to understand God’s will for their present circumstances. For Jew and Christian alike ancient Scripture continued to speak a guiding message into each new time and circumstance. Both communities searched the prophets to understand present history. This is particularly illustrated by the scriptural interpretation of the Qumran community, who explained details of their own sectarian history by recourse to a pastiche of biblical passages distinctively interpreted in their pesherim (commentaries), including the Qumran Psalms Scroll and the fragmentary commentaries on the psalms discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

In the Christian New Testament, no book is cited more often as a warrant for understanding the life of Jesus than the book of Psalms. Particularly influential are Psalms 2 and 22, which mirror the two sides of Jesus that the church came to regard as key to understanding his work: his messianic sonship (Ps. 2) and his vicarious, sacrificial death (Ps. 22). But pride of place certainly goes to the messianic interpretations of Psalm 110, the most frequently cited psalm in the entire New Testament. Thus, in the end, while Jews and Christians shared a reverence for the psalms as Scripture and a method of engaging them for contemporary guidance, the Christian use of the psalms to buttress their claims about Jesus must have represented a major point of separation.

Through the past nineteen centuries, Christian use of the psalms has continued to recognize the three distinctive elements of their character that we have mentioned above. (1) The psalms serve as guides to personal, private prayer. (2) They continue to find their way into Christian worship through liturgy and through metrical versions for singing. When the psalms themselves are not sung directly, they often form the basis of many hymns and praise choruses. (3) Finally, the psalms still serve as a scriptural resource for the divine Word of God speaking to our present circumstances.

The Poetry of the Psalms

Understanding Poetic Conventions

I DON’T KNOW what you think about poetry. Many people either love it or hate it. Some find it moving and compelling, while others simply do not understand it. Some respond to poetry emotionally, while others appreciate the technical skill by which poets choose and arrange their words to create alternative worlds of powerful vision.

Regardless of your evaluation of the poetic form, if you are like most people, you have some sense of it—some idea of what makes it poetry and not prose. Your experience may be limited to childhood nursery rhymes and juvenile doggerel. Or you may have studied poetry broadly and deeply, in school or privately. You may even be a poet yourself.

A poem is not a laundry list or a legal document. Nor is it a novel or a letter, although these latter may have “poetic” moments—when they share some of the distinctive qualities of poetry. Part of this distinctive character of poetry we recognize intuitively. To this I will return directly. But mostly we recognize poetry because it corresponds to a body of conventions that sets it apart—that distinguishes poetry from other forms of written (and spoken) communication. Most of these conventions we have learned, either picking them up casually through exposure to poetry or formally through a direct process of instruction.

In the Western world, dominated by Eurocentric ways of thinking, three primary conventions have characterized classic poetic composition: rhyme, rhythm, and meter. Rhyme, the use of similar or identical sounds to conclude multiple lines of poetry, is perhaps the more obvious poetic technique:

I never saw a purple cow.

I never hope to see one,

But, I can tell you anyhow,

I’d rather see than be one!3

The arrangement of rhymes within a poem—whether on successive or more distant lines, or even within a line—enables the poet to introduce variety into the composition, to establish controlled, regular movement, or in some instances to define the nature of the poetic form and distinguish it from other similar ones. All sonnets, for example, are made up of fourteen lines of poetry of identical meter. How the lines are grouped and how the rhymes are distributed among the lines reflect formal patterns that clearly distinguish English (Shakespearean) sonnets from their Italian (Petrarchan) counterparts.

A second obvious (though less obvious than rhyme!) poetic convention that characterizes classic Western poetry is rhythm—the attempt to regularize various combinations of stressed and unstressed syllables in poetic lines. Such concerns are actually reflective of the originally oral character of poetry, since this kind of stress and lack of stress is only operative in spoken language. All spoken language naturally employs a variety of combinations of stressed and unstressed syllables (to avoid any stress in speech is to be monotone and is considered peculiar or unnatural). Classical Western poetry differs from normal speech by limiting the appearance of stress and unstress to a controlled and regular pattern.

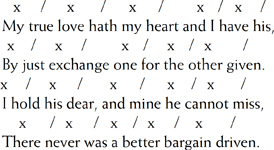

Two frequently employed forms of poetic rhythm can serve to illustrate the point. In the first example the rhythm is made up of a series of single unstressed syllables [x], each of which is followed immediately by a single stressed syllable [/]. The result, if exaggerated slightly, produces a rather rocking rhythm and is formally described as iambic rhythm. (Notice also the use of rhyme in alternating lines.)

Dactylic rhythm provides a suitable contrast to the previous example. In this second form of rhythm, a single stressed syllable is followed immediately by two unstressed syllables.

Other common types of poetic rhythm include trochaic (a single stressed syllable followed by a single unstressed syllable [/ x]) and anapestic (two unstressed syllables followed by a single stressed syllable [x x /].

Along with rhythm, meter provides the basis for a formal analysis of poetic rhythm in combination with line length. In metrical description, each occurrence of the regular rhythmic pattern is considered a foot. The name of the pattern (iambic, anapestic, dactylic, etc.) combined with the number of feet in a given line is considered the meter of that line. Our first example above is composed of single unstressed syllables followed by single stressed syllables. This is the iambic pattern. Lines 1 and 3 each contain four repetitions (feet) of this pattern and are therefore described as iambic tetrameter. Lines 2 and 4 have only three feet and represent what is called iambic trimeter.

Shakespeare’s favorite meter was iambic pentameter—five repetitions of the iambic pattern described above in each line. Most of his plays employ this convention, subtly spreading the lines with their characteristic meter across the dialogue. Other poets have employed a variety of metrical combinations to achieve creative effects. Witness the opening passage of Longfellow’s The Highwayman, which uses varied meter to mimic the galloping gait of the highwayman’s steed.

The wind was a torrent of darkness among the gusty trees

The moon was a ghostly galleon, tossed upon cloudy seas,

The road was a ribbon of moonlight over the purple moor

When the highwayman came riding, riding, riding,

The highwayman came riding, up to the old inn door.

We might think of these conventions as “rules” that must be followed to create poetry. As children we often follow them slavishly to create youthful celebrations of fancy, fantasy, and love. Only later do we come to a more mature understanding that these “rules” of poetry are in reality only our after-the-fact attempts to describe what poets do and so to bring order to our understanding of poetry. Poets are wont to rebel against too much convention as stultifying to their artistic creativity. One important “rule” of poetic convention is that rules may be stretched and even broken to achieve a desired effect.

Modern poetry frequently departs from all these poetic conventions. Blank verse, for example, retains both rhythm and meter (iambic pentameter) but avoids rhyme altogether. Free verse, on the other hand, demonstrates no regular rhythm, rhyme, or meter, preferring to conform the poetic structure of a poem only to the expressive needs of the poet. Obvious poetic conventions are left behind along with the most recognizable landmarks of poetry. The distinction between poetry and prose becomes more difficult to observe and to articulate.

It may be difficult, but for the most part it remains possible to recognize poetry. A poem is still a poem and not a grocery list. Even without signposts it may be possible to tell what part of the country you are in. So, even without obvious rhyme, rhythm, and meter, one can distinguish a poetic composition from its more prosaic counterpart. It is at this point that those more intuitive characteristics I mentioned before become important. Let me mention just two of these that I have found helpful: imagery and compression.

Because poetry is essentially an oral medium, relying on a memorable word and a receptive ear, it is filled with vivid imagery to tease the ear and engage the visual and emotional receptors of the brain rather than the merely rational. While it is true that prose can and does employ imagery, poetry far exceeds prose in the amount of imagery it exhibits. For prose, imagery is a subsidiary tool trotted out in support of the author’s primary object. With poetry, however, imagery is the dominant stock in trade to cement the poet’s ideas securely in the mind and heart of the hearers.

Together with imagery compression offers a second intuitive way we distinguish poetry. I know of no better illustration of compression than to observe carefully how most modern translations of the Bible present poetry and prose on the printed page. If you turn in your Bible to, say, Genesis 6 (the beginning of the Flood narrative), you will find the page covered with type from margin to margin—perhaps in columns, but still consistently filled with type.

Now turn to Psalm 119, Proverbs 14, or Isaiah 60. You will immediately notice considerably more white space on these pages—less type. The difference is that, while the Genesis text is prose, these last three are set in poetic lines. The lines of poetry are relatively equal in length and considerably shorter than the sentences found in the prose section. That begins to give a sense of what I mean by compression. Poets choose their words carefully. They seek just the right words to communicate their meanings with power and punch. Not just any word will do.

Prose is more expansive, achieving clarity of meaning by adding words and sentences to define and refine meaning. But poetry tends to be more concise, relying on the power of words rightly chosen and arranged to communicate the desired effect. The result is compression—tightly constructed lines of similar length, with an economy of carefully selected words.

Because of compression, poetry often seems condensed and powerful. Reading a poem can be a little like eating a spoonful of honey directly from the jar. The experience can be overpowering and unsettling. Each word is important and contributes to the whole. None can be lightly exchanged without altering the effect of the whole. That is part of the purpose of poetry. The careful selection and arrangement of words can have a powerful effect on the reader—recreating a spiritual, emotional, and intellectual world in which one is challenged to see, feel, and understand differently.

But because of compression, poetry is also less able to explain and refine its meaning than is prose. Poetry must rely on the effect of its words and images to carry meaning. Thus, poetry can sometimes be more ambiguous and difficult to follow. Because of the compression of meaning into few words, things are not “spelled out,” and the concentrated words may offer more than one possibility for interpretation. That is the beauty (and sometimes the frustration) of poetry. Often, it can take as much care to understand good poetry as it does to construct it!

The Art of Hebrew Poetry

FROM THE PREVIOUS discussion it is clear that poetry operates within a set of conventions that shape it, provide boundaries for it, and ultimately distinguish it from other forms of oral and written speech—in particular, prose. These conventions, whether overt and obvious (e.g., rhyme, rhythm, and meter) or more subtle (e.g., use of imagery or compression), provide the artistic structures that challenge the poet’s task. Ultimately these conventions, along with a poet’s acceptance, implementation, and even resistance to them, conspire together to define the borders of the poetic act that allows us, the readers, to recognize a poem for what it is.

It would be simpler, I suppose, if all cultures adopted the same set of poetic conventions. (Simpler, but not so creatively rich and exciting!) We would then be able to transfer our poetic understanding and appreciation (or lack thereof!) across cultural and linguistic boundaries. But different cultures and different peoples—separated by place and time—step to distinctively different poetic rhythms and conventions. In each society, poetry operates by canons of conventions distinct from prose, but those conventions are not necessarily shared from society to society, culture to culture.

The Hebrew poetry of the Bible, of which the book of Psalms is an important part, is no exception. It conforms to a group of poetic conventions that give it shape and character, and these conventions distinguish it from Hebrew prose. In some of its more subtle characteristics (e.g., use of imagery, compression), Hebrew poetry has much in common with universal poetic expression. Even some of its more specific stylistic features (to be discussed below) find counterparts in the poetry of other cultures. But by and large, most of the explicit conventions of Western poetry discussed above are missing in Hebrew poetry.

Rhyme. For example, Hebrew poetry shows no clear evidence of a purposeful use of rhyme. Occasional occurrences of apparent rhyme are normally the result of parallel structures employing similar verbal forms with the same inflected endings. Such rhymes are the result of grammar and happenstance, not the choice of the author to produce rhyme combinations. Moreover, such occurrences are infrequent.

Meter. While certainly rhythmical, Hebrew poetry has no generally recognized or persuasively demonstrated system of meter. It is generally agreed that Hebrew poetry did exercise certain limitations on the length of lines. Thus it is possible to observe a relative balance between poetic lines. The use of ballast components to compensate for ellipses in parallel lines is another indication that poetic lines conformed to similar expectations of length. Having admitted this, however, it remains unclear precisely what factors were at work in determining line length.

Of the numerous attempts made to describe and delineate such a metrical system for Hebrew poetry, two deserve particular notice.

Stressed syllables. The earlier of the two systems remains as the more persuasive. Here meter is related to the number of stressed syllables in each poetic line. In spoken communication, almost every word bears some stress in pronunciation. The stressed-syllable system makes a distinction between word stress (the stress placed on individual words when spoken singly) and tone stress (the stress placed on groups of words combined together in rapid speech or especially in phrases encountered in singing). Ancient oral poetry was akin to song, and probably much psalmic poetry was intended to be performed with music. Note the combination of words and syllables into phrases in the following examples. In each, phrases are produced composed of two or more independent words that share a single stress in rapid speech. In Psalm 1:1, for example, loʾ-ha-lak, loʾ-ʿa-mad, and loʾ-ya-šab are all combinations of the negative loʾ and a perfect verb form.

ʾaš-re | ha-ʾiš | ʾa-šer |

loʾ-ha-lak | ba-ʿa-ṣat | re-ša-ʿim |

u-be-de-rek | haṭ-ṭa-ʾim | loʾ-ʿa-mad |

u-be-mo-šab | le-ṣim | loʾ-ya-šab |

The phrases grouped together with hyphens (-) represent units that would receive a single stress in singing or rapid speech. Such stress on phrases is called tone stress.

This first theory of Hebrew meter suggests that lines of poetry demonstrate regular patterns of tone stress in their lines. In Psalm 1:1, the number of words in each line, and therefore the number of word stresses, vary from line to line, but the tone stress remains fixed (three per line).

The system is somewhat akin to our own concept of musical “time” with a number of beats per musical passage. A 3/4 time is distinctively different from 4/4 time, as you can tell from singing “Away in a Manger” (3/4) and then “Jingle Bells” (4/4). Clearly the beats accord with musical phrasing, not with individual word stress.

This discussion makes the system sound clear and convincing. I wish it were only so simple. In the real world of Hebrew poetry, it is often difficult, if not impossible, to determine a continuing pattern of meter. Some attribute this to textual corruption in transmission and seek to restore the pattern by textual emendation. It is, however, problematic in my opinion to prove a theory by emending the text when it does not correspond to one’s expectations. It has too often happened that difficult texts are changed “because of the meter,” as the critical notes in BHS frequently demonstrate. Elsewhere it may be that certain elements were intended to stand outside the meter of a poem or that we simply have got the lines or word combinations wrong.

The description of meter based on tone stress does seem to work sometimes, but it cannot be consistently demonstrated in all cases. Thus it remains a tantalizing possibility. Perhaps the most persuasive assessment of the findings is that Hebrew poetry does seem to preserve relative balance in stressed meaning units grouped as phrases. This might reduce the need for perfection in poetic description—perfection that probably exceeds our ability to grasp it, given the long history of transmission of the biblical text and the ancient silence on Hebrew poetic technique.

Having said this, it is clear that relative similarity of line length is present in most Hebrew poetry. It is also clear that intentional patterns involving different line length can be observed and are in some instances significant. One of the clearest of these is the “limping meter” associated with the biblical laments. This form is composed of a three- or four-stress line followed immediately by a line with only two stresses, as in Lamentations 1:1:

ya-še-bah | ba-dad | ha-ʿir-rab-ba-ti-ʿam |

ha-ye-tah | ke-ʾal-ma-nah | |

rab-ba-ti | ba-go-yim | śa-ra-ti-bam-me-di-not |

ha-ye-tah | la-mas |

Some scholars think this rather hobbling rhythm mimicked or even accompanied a limping dance that visibly demonstrated the grieving and suffering of the lamenters.

Syllable counting. The second theory of meter in Hebrew poetry revolves around counting the number of syllables in poetic lines. The idea is that poets created lines containing identical numbers of syllables or at least some regular and recognizable pattern of syllables. This system developed as an alternative to the earlier theory of word stress and in response to that system’s failure to explain consistently all features of biblical poetry.

It is obvious that syllable counting is related to relative balance of line length, but it seeks to bring greater precision to its description. Several significant difficulties face the proponents of this view. (1) Since Hebrew was originally written without indications of vowels, the syllabic structure of this ancient language has always had a certain degree of ambiguity. Add to this the fact that the consonantal text reflects several different dialects of Hebrew across a period of a thousand years or more, and the complexity of the issue becomes immense.

(2) The vocalic system represented in our current Hebrew text was not fully developed until the sixth or seventh century A.D. There are three competing systems of vocalization known (the Tiberian system that is generally employed, the Babylonian system, and the Palestinian system). These alternate attempts to fix pronunciation demonstrate some significant differences in their interpretation of specific texts.

These vocalic systems represent the way these biblical texts were pronounced in the sixth century A.D., and it is clear that pronunciation only imperfectly fits the consonantal text at many points. As a result, attempts to describe the original syllabic structure of poetic texts almost always involves hypothetical reconstruction based on some theory as to how Hebrew was pronounced at the date when the text in question was assumed to have been produced.

Such hypothetical reconstruction is exceedingly complex and offers too much opportunity for manipulation of the text to support one’s theory of syllable counting. This can lead to circular reasoning where the system is “proved” by the emendation of texts because of the demands of the system. For this reason there has been much disagreement, even among proponents of the method, and the theory lacks consistent ability to persuade.

Conclusions. What these two attempts to describe the nature of Hebrew poetic meter do demonstrate is the existence of relative balance in poetic line length. Both systems are able to find supportive examples because there does appear to be some limitation to the length of lines. Lines do not simply run on forever but stay within relative bounds. Beyond this, neither system has yet to provide consistent explanation of all existing texts. While the system based on tone stress seems more persuasive in my opinion, we may have to accept the fact that, because of the historical distance and theoretical ambiguity that stand between us and the text, a full understanding of the ins and outs of Hebrew meter will probably continue to elude our grasp.

Techniques of Hebrew Poetry

OBVIOUSLY, THE HEBREW poets had at their disposal the broad range of literary and stylistic techniques known to poets throughout the ages. Metaphor, simile, personification, onomatopoeia, and more offered each biblical poet ample opportunity to shape and texture individual compositions personally. But without such familiar poetic features as rhyme and meter, Hebrew poetry can often strike us as strange and uncomfortable. As we enter the world of the psalms, therefore, we may feel we have taken a wrong turn and are moving through alien terrain. So, to understand and appreciate the poetry of the biblical psalms, we will need to construct a new map of the land; we will need to become familiar with a new set of conventions that reflect the world of Hebrew poetry in general and of the psalms in particular.

Parallelism. It has long been recognized that the most distinctive characteristic of Hebrew poetry is to be found in the frequent linking of successive lines of poetry in a manner that emphasizes grammatical, structural, and thematic similarities between them. This relationship between lines has been traditionally called parallelism. The sense of this description is that after the statement of an initial line, a second (and sometimes a third) line is generated that shares some obvious grammatical-structural similarities with the first and yet redirects the focus of the first through alternate words and expressions. The close grammatical-structural similarity between lines provides continuity that emphasizes the parallel character of the two lines, while the distinctive phraseology of each phrase lifts the phenomenon beyond mere repetition and offers the opportunity for expansion or advancement on the original line’s meaning.

At least from the time of Robert Lowth’s De sacra poesi Hebraeorum . . . (1753), a relatively standard terminology has been used to describe the variations of parallelism within Hebrew poetry. It is generally agreed today that these terms only inadequately describe the categories under consideration, and in some cases they are even misleading. Although they are well entrenched in the discipline, I will presume to replace them with more accurately descriptive terms here while noting the traditional terms at the first appearance of each.

Affirming parallelism.6 This first of the traditional forms of parallelism comes closest to repetition or restatement. In this case, the second line restates the first in a similar or positive fashion while employing distinctive phraseology. This can approach almost exact repetition in some instances.7

So God created the ʾadam in his image;

in the image of God he created him.

—Genesis 1:27

In this example, except for the rearrangement of parallel elements, the second line restates the first with little advance or addition. Perhaps the phrase “in the image of God” clarifies the more ambiguous “in his image” of the first line, but the overall effect here is repetition for emphasis rather than advancement or refinement of thought.

In other cases the positive parallel of elements between lines is preserved, but the terminology employed in each is more distinctive.

Wash away all my iniquity

and cleanse me from my sin.

—Psalm 51:2

There is close and positive structural parallel between these two lines: similar imperative verbs (“wash away” vs. “cleanse me”) and similar noun constructions (“my iniquity” vs. “my sin”). There is also positive parallel in the meaning of these two lines; washing away my iniquity is much the same as cleansing me from my sin. However, the second line does not simply restate the meaning of the first but advances or expands it by adding new nuances to the thought world created.

Sometimes the advancement offered by the second (or third) line can be quite unexpected and significant. If we return to Genesis 1:27, we will discover that a third line adds another affirming parallelism to the first two.

So God created the ʾadam in his image;

in the image of God he created him;

male and female he created them.

By comparing the related structural elements in these lines (“God created/he created/he created”; “the ʾadam/him/them”; “in his image/in the image of God/male and female”), we conclude that the new phrase in the third line (“male and female”) is intended to expand (in an unexpected way) our understanding of what it means to be created in God’s image. This is clearly not simple repetition but an important advancement in the thinking of the poet!

Thus, in affirming parallelism, a second or third line of poetry restates a preceding line in a positive fashion that maintains continuity with the structure and meaning of the first, while in subtle (or not so subtle) ways expanding and advancing the thought begun there through the introduction of alternate expressions into the growing thought world created by the combination. Recognition and appreciation of the art and subtlety of this form of poetic expression will require additional study and exposure. A few examples are provided below to illustrate the variety of synonymous constructions encountered in the Hebrew Bible.

Their mischief returns upon their own heads,

and on their own heads their violence descends.

—Psalm 7:16

My hand shall always remain with him;

my arm also shall strengthen him.

—Psalm 89:21

Like those forsaken among the dead,

like the slain that lie in the grave.

—Psalm 88:5

Opposing parallelism.8 A second form of parallelism in Hebrew poetry is clearly distinguished from the first. In this construction, the second line maintains clear continuity with the structure and meaning of the first but relates to it in a negative rather than a positive fashion. A few examples should bring clarity to this description.

A wise son causes a father to rejoice;

a foolish son is a pain to his mother.

—Proverbs 10:1

The similarity of structure and meaning is obvious: A certain type of son has a particular effect on a parent. At this level, the parallel between lines is almost exact. But rather than the positive restatement characteristic of affirming parallelism, these lines demonstrate a decidedly negative or contrasting relationship. The “wise son” and resultant “joy” of relationship in line 1 is contrasted with the “foolish son” and the consequent “pain” in line 2.

The contrasting character of opposing parallelism has great potential for instruction because it presents in brief compass both a positive example and a negative caution that point the student to the more prosperous of two paths (wisdom and folly; righteousness and wickedness) that the biblical sages recognize as the basic opportunities of life. As a result of this didactic potential, opposing parallelism is frequently found throughout the biblical wisdom literature—especially in Proverbs, where it appears as the most common feature of chapters 10–29.

He who keeps the commandment keeps his life;

he who despises the word will die.

—Proverbs 19:16

The heart of the sage is in the house of mourning,

but the heart of fools is in the house of mirth.

—Ecclesiastes 7:4

If he withholds the waters, they dry up;

if he sends them out, they overwhelm the land.

—Job 12:15

This form is not limited to the wisdom literature, however, but appears regularly in the psalms and other Hebrew poetry. Here are a few more examples to illustrate the varied nature of opposing parallelism.

Yahweh watches over the sojourners,

he upholds the widow and the fatherless;

but the way of the wicked he brings to ruin.

—Psalm 146:9

The first two lines represent affirming parallelism and expand on the theme of God’s care for and protection of the helpless in society (“watches/upholds”; “sojourners/widow and fatherless”). In a parallel but opposing manner the third line (“brings to ruin”) introduces the contrasting fate of the wicked at the hand of a God concerned with justice.

The wicked borrows and cannot pay back,

but the righteous is generous and gives;

for those blessed by Yahweh shall possess the land,

but those cursed by him shall be cut off.

—Psalm 37:21–22

Two sets of opposing parallel lines appear within this single verse. In the first set the wicked and righteous clearly oppose each other, as do their respective relationship to finances (borrowing without repayment vs. generous giving). In the second set, the poet contrasts the futures of those who are blessed or cursed by Yahweh. The rather harsh contrast introduced by the use of the parallel phrase “cut off” (normally implying death!) adds a new dimension to the blessing of the land that Israel experienced and ultimately lost in the Exile. Loss of the land is here understood to represent not merely geographical dislocation but physical and, even more importantly, spiritual death!

Advancing parallelism. The third form of parallelism traditionally recognized is really not parallel at all. In this type, the second line has lost all semblance of similarity of structure, syntax, or meaning with the preceding line and unabashedly charges ahead, advancing and furthering the poet’s thought. The name traditionally applied (synthetical parallelism) is, therefore, doubly misleading. There is no more parallel here than there is synthesis. The philosophical term synthesis that is pressed into thankless service here assumes a preceding thesis statement with a countering antithesis, which then interact to create a new and better response or synthesis.

It has long been recognized that this terminology in relation to Hebrew poetry is confusing at best and misleading at worst. Although the term is entrenched in usage, I prefer in the discussion that follows to use the more accurately descriptive term advancing parallelism, fully realizing that in this case parallelism is an inadequate descriptor.

In advancing parallelism, then, after an initial line, a second (or third or, in some cases, even more!) line continues the thought, theme, or narrative of the poem without any obvious concern to maintain grammatical, structural, or thematic similarity to the initial line. The poem simply continues to develop its theme, while parallelism fades from view. This lack of parallel structure may be limited to a single set of poetic lines or may be more extensive in nature, affecting several verses or even whole compositions.

Again, let’s consider several examples to get a sense of the varied appearance of advancing parallelism.

Our God is in the heavens;

he does whatever he pleases.

Their idols are silver and gold,

the work of men’s hands.

—Psalm 115:3–4

In each of these couplets, the second line builds on the preceding line without being parallel to it grammatically, structurally, or thematically. The first couplet goes on to describe the exalted freedom of the God who resides in the heavens—a freedom that is certainly related to his exalted position and perhaps even derived from it, but it is not expressed in any sense of parallelism. The second couplet begins by describing the inanimate stuff (albeit rich) from which idols are constructed, but it continues in the second line to drive home their inferiority to the free God of the heavens by emphasizing the idols’ creation by human hands. Again, there is relationship, connection, and continuity between line 1 and line 2, but no clear, or even subtle, parallelism.

You have put more joy in my heart

than they have when their grain and wine abound.

In peace I will both lie down and sleep;

for you alone, Yahweh, make me dwell in safety.

—Psalm 4:7–8

Once again the second line of the first couplet simply carries the thought begun in the first on to its proper conclusion, emphasizing the great joy the psalmist experiences in relation to Yahweh in contrast to those who find their joy in the abundant grain and wine he provides. The next couplet employs the second line to describe the basis of the psalmist’s security in Yahweh that makes it possible to lie down and sleep peacefully, even in the face of personal attack and distress described earlier in this psalm.

Advancing parallelism clearly offers a poet maximum flexibility in the creation of lines that develop, direct, and advance the movement of a poem. Freed from the relative constraints of the demands of parallel structure, the poet can introduce more complex and extended argumentation that goes beyond the more restrictive, two-line format characteristic of parallelism. As a consequence of this freedom, compositions can become more flowing, less fragmented, and more unified (and in some instances longer!). For this reason alone, advancing parallelism is a frequent player in Hebrew poetry. Some psalms are even primarily composed of synthetical lines with little or no attention to parallelism at all. Take a look at Psalms 110 and 111 in this regard. Neither makes much use of parallel forms. The interior dialogue sections of the book of Job and parts of Ecclesiastes owe much of their subtly and complexity to their ability to advance, expand, and sustain the discussion through frequent use of advancing parallelism.

So, in advancing parallelism, Hebrew poets broke with the strictures of similarity with the preceding line and experienced their greatest freedom to advance, direct, redirect, and structure the thought of a poem. How differently poets can proceed from the same starting line is illustrated in the examples below.

O sing to Yahweh a new song;

sing to Yahweh, all the earth.

—Psalm 96:1

O sing to Yahweh a new song,

for he has done marvelous things!

—Psalm 98:1

O sing to Yahweh a new song,

his praises in the assembly of the faithful.

—Psalm 149:1

Here, the same initial line gives rise to three distinctively different treatments. The first (96:1) offers a variation on the synonymous form by expanding the second line (“all the earth”) to compensate for the omission of an element (“a new song”) from the first. This expansion to replace an ellipsis is sometimes referred to as a ballast line or element.

The third set of couplets is another example of ellipsis with compensation in the second line. Here, however, it is the lead phrase (“Sing to Yahweh”) that is omitted in the second line. It is perhaps more correct to say that this phrase is understood (by both poet and reader) to govern both lines. As a result of this ellipsis, the remaining phrase (“his praises in the assembly of the faithful”) is greatly expanded over its parallel (“a new song”) while the lines together remain synonymous in relationship.9

In the middle example (98:1), the initial line is continued synthetically in the second. The poet goes beyond the opening invocation to praise Yahweh with a justification of Yahweh’s praiseworthiness (“for he has done marvelous things!”). These very different directions from the same starting point demonstrate just how much flexibility the Hebrew poetic system afforded creative poets seeking new and unique forms of expression.

Here is another group of similar examples.

Turn to me and be gracious to me;

give your strength to your servant,

and save the son of your handmaid.

—Psalm 86:16

Turn to me and be gracious to me,

for I am lonely and afflicted.

—Psalm 25:16

Turn to me and be gracious to me,

as is your wont to those who love your name.

—Psalm 119:132

Once again, the same opening line generates three distinctive responses. In the first (86:16), the poet continues with two lines that are synonymously related to each other but not to the first line. The synonymous couplet explores how the psalmist desires God to turn and be gracious (by strengthening and saving). In the second example (25:16), the successive line explains why the psalmist needs God to return (“for I am lonely and afflicted”), while the focus of the third passage (119:132) is the divine character that undergirds the poet’s hope for a gracious divine response.

Climactic parallelism. There is one additional Hebrew poetic form that has received attention of late under the rubric of parallel structure. Again, there is some discussion whether climactic parallelism, as this feature has been called, is an altogether happy designation. As will be clear from the examples that follow, there is continuity of thought and syntax between the related lines. In fact, at least part of the initial line is repeated verbatim in successive ones. The question in my mind, however, is whether the few examples we have of this form constitute an independent type of parallelism or whether they rather illustrate an expansion and adaptation of the more recognized forms. Let’s look at two examples.

Ascribe to Yahweh, O heavenly beings,

Ascribe to Yahweh glory and strength,

Ascribe to Yahweh the glory of his name;

Worship Yahweh in holy array.

—Psalm 29:1–2

The interrelation of the lines in this example is obvious. The threefold repetition of the opening imperative phrase (“Ascribe to Yahweh”) binds the first three lines together, while the fourth and final line offers a summation of the whole complex. Lines 2 and 3 form together a clear example of affirming parallelism, with “glory of his name” in line 3 providing expansion and subtle redirection of the theme introduced by “glory and strength” in line 2. It is not simply glory and strength that is at issue here, but the glory and strength that proceed from the divine name (and thus the character and essence) of Yahweh.

It is only the placement of line 1 with its identical phrase that lifts this composition to a new level of poetic intensity. The completion of the initial phrase is postponed by the intrusion of the “heavenly beings” called to acknowledge and exalt the name of Yahweh. This delay intensifies the interest of the hearer/reader, who must wait for the resolution until the end of the next line. The intensity is heightened even further by the thrice repeated command, “Ascribe to Yahweh. . . .”

A similar use of triple repetition to intensify the effect of poetic lines is found in our next example.

The floods have lifted up, O Yahweh,

The floods have lifted up their voice,

The floods lift up their roaring.

—Psalm 93:3

Here the floods most likely represent the chaotic waters subdued by Yahweh at creation (associated in more general ancient Near Eastern mythology with precreation deities). These powerful waters, which represent a potent threat to the very human poet and reader, rise up in tumult and appear to endanger the very fabric of the orderly creation established by God—the creation on which the very existence of humans depends. Perhaps the scene is intended to reflect the Flood narrative of Genesis 6–9, where the chaotic waters restricted by Yahweh at creation are unleashed once more and threaten to dissolve creation once and for all.

As in the previous example, lines 2 and 3 are synonymously parallel, with line 3 intensifying the growing effect of line 2 by substituting the powerfully descriptive “roaring” for the more pallid “voice.” Line 1 provides additional intensification—delaying the completion of the initial phrase (“The floods lift up”) by inserting the vocative address to Yahweh. The result is a poetic depiction of the gradual ascent of the powerful clamor made by the tumultuous waters in their opposition to God.

You may now understand why I questioned at the outset whether these examples illustrate an independent form of parallelism. There are so few examples of this type offered, and those examples exhibit strong characteristics of affirming parallelism (lines 2 and 3 in the examples above) and advancing parallelism (the relation of line 1 to lines 2 and 3). It seems best, in my estimation, to view climactic parallelism as a particularly artful adaptation of traditional forms of parallelism for purposes of intensification.

Summary. For the purposes of our general discussion, then, the three traditionally recognized forms of parallelism (affirming, opposing, and advancing) constitute the basic literary arsenal of the ancient Hebrew poet and provide the peculiar flavor that makes this poetry distinctive. Our discussion has for the most part remained rudimentary, and there remains much for the student of Hebrew poetry to learn through direct experience and observation. Only through such personal exploration can one gain a more complete sense of the subtle, nuanced variations of form that demonstrate biblical poets’ skill and mastery in pursuing their craft.

Before we leave the discussion of Hebrew poetry, however, I will discuss five other conventions or techniques. While these stylistic features are not unique to the Bible, their use adds dimension and breadth to our understanding of the psalms and biblical poetry.

Word pairs. The phenomenon of parallelism in Hebrew poetry highlights the close relationship that can exist between parallel words and phrases in the related lines. As we have seen, a significant word in one line can be augmented or expanded by its parallel in the next. In some instances this expansion may represent mere stylistic variation. But on most occasions the second word adds a significant semantic or theological dimension to the first. This is particularly clear in the first example I used of affirming parallelism (Gen. 1:27). The phrase in line 1 (“in his image”) is only slightly varied in line 2 (“in the image of God”), but it is significantly expanded both semantically and theologically in line 3 by the parallel phrase “male and female.”

The important theological advancement accomplished in these three lines is illustrative of the kind of use that can be made of parallelism. James Kugel is certainly right when he stresses the “seconding” effect of parallel lines: “A, and what’s more, B.” The sum of the two parts is always more, in his opinion, than mere repetition.10 One must always take into consideration this expansive nature of parallelism in interpreting couplets. In most instances the poet is building a semantic context in which the subtle nuances of two or more words brought together in parallelism expand the possibilities for understanding.

The same expansion can also be subtly understood in opposing parallelism. Here the negative parallel can once again add nuances to our understanding of the original word. Take, for example, the concluding verse of Psalm 1:

For God knows the way of the righteous,

but the way of the wicked will perish.

—Psalm 1:6

The initial line leaves open what it might mean for the path of the righteous to be known by God. But the negative parallel in the following line makes it clear that God’s knowing is a source of protection and preservation not experienced by the wicked. Thus, the semantic world in which the ideas of the poet operate are significantly expanded by juxtaposing these two phrases and their nuances. Thus, it is important for an interpreter to recognize that more than repetition is at work behind the words chosen to be in parallelism. Through the chosen words the biblical writer creates an expanded semantic thought world.

Traditional word pairs. The choice of word pairs for parallelism can sometimes become a matter of fixed, traditional association. Through long usage, certain words become connected as expected parallels balancing their respective lines. “Wisdom” is normally balanced by “folly.” The “wicked” are most often paralleled by the “righteous.” “Heaven” is most often linked with “earth.” “Man” (ʾadam) finds its reflex in many instances in “son of man” (ben ʾadam). Many other commonly employed word pairs have been recognized as operative in Hebrew poetry.11

Traditional word pairs such as these can even play a role in textual criticism, as attempts to restore the fragmentary Canaanite religious texts from Ugarit (Ras Shamra) demonstrate. These texts, written in an alphabetic cuneiform script on clay tablets, were discovered in the late 1920s in excavations at a site on the coast of northern Syria. Among other documents, these texts include poetic religious documents from the third millennium B.C. in a language closely resembling ancient Hebrew. The poetry used in these ancient texts also employs parallel lines and exhibits extensive use of traditional word pairs.

When a clay tablet has been damaged so that parts of lines are no longer legible, it is often possible to make a confident reconstruction based on the plausible anticipation of fixed word pairs. Occasionally such a scholarly conjecture has been proven correct by the discovery of additional copies of the text where the lines in question are still extant or by comparing repeated passages elsewhere in the same tablet. It has now become common practice for biblical textual critics to suggest emendation of incoherent or difficult poetic passages on the basis of expected completion of fixed pairs.

The frequent appearance of so many fixed pairs in parallel lines ought perhaps to caution us against making too much of the possibilities for theological expansion in such cases. Is the poet’s choice of terms driven by a desire to nuance the literary context? Or is it determined by the expectations of the fixed word pair? Such caution is probably appropriate. However, the use of words as fixed pairs does not prohibit their use singly in other contexts or even in connection to other words in parallel lines. “Man” (ʾadam) is not always paralleled by “son of man” (ben ʾadam), nor is “wicked” inexorably connected to “righteous.” Fixed pairs represent only one possible word choice that Hebrew poets could use to good effect.