THE PLACE

A comfortable place to live has as many bathrooms as there are people in residence, plus one for guests. It is like the formula for making tea—one for everyone there and one extra for the pot. (This is a comparison Miss Manners suddenly realizes she does not care to continue.) It also has twice as many closets, a gymnasium and an indoor parking lot. Such houses actually exist, although not exactly at all price levels. What astonishes Miss Manners even more than their cost is the other amenities that dream houses now require to accommodate the way the people who can afford to buy them choose to live.

It has become obligatory to have an enormous eating area in the kitchen so that nobody has to eat in the dining room and (when we are talking high luxury) a facility for storing and heating food near the bedrooms so no one has to eat in the kitchen, either. The kitchen is used to entertain guests so they don’t have to use the living room. This entertainment now consists of letting the guests watch what used to be the preparations for entertaining guests.

The family doesn’t want to use the living room, either. Nobody does. It’s considered a nice place to have and to furnish, but not a place to live in. Miss Manners suspects that living rooms are now so often done all in white out of some dim memory of bridal white as a symbol of the untouched state. Now there must be a family room to take over the living function of the living room, but that is no longer where you might find the family. Another room has done to the family room what the family room did to the living room. This one is known as the entertainment center or media room; before that, it was called the computer room or the television room. The name keeps changing because the room’s purpose is to house electronic equipment the family must share—first it was the only upstairs telephone, then the television set, then the computer. When the object is no longer a novelty and each inhabitant gets one in his or her bedroom, the family moves on to the next luxury. Right now, this room might have the only movie-theater-sized television screen in the house, so it is where the children do their studying.

There are at least two other rooms properly fitted up as studies, but those are maintained as separate retreats for the only adults who have to share a bedroom, which is no longer a bedroom but a master suite. Couples used to achieve privacy from each other and the children by going into the bathroom and locking the door until forced to respond to desperate pleas, and Miss Manners might have thought that the affluent would be all the more easily able to do this because they have more bathrooms. No such luck. The huge modern his-and-hers bathrooms have double sinks, such as Miss Manners remembers from her dormitory days, implying that other people are expected to drop in.

Far be it from Miss Manners to suggest that people should eat in their dining rooms, live in their living rooms and be alone in their bathrooms. If the rich want to show their solidarity with the less fortunate by huddling into a few small rooms above lobbylike spaces they never use, that is surely their privilege. What does concern her is what the system says about the attitudes of the inhabitants and their guests towards themselves and one another. Much as she likes the old plan, she would have thought that the modernization of the old-style formal house would result in less wasted space and a warmer atmosphere. Instead, there seems to be more space than ever devoted to pure show. Once, it was just the front parlor that might be saved for company and grand occasions; now it’s the dining room as well, and the company has been banished along with the family.

The old plan for a luxury house recognized the need for privacy with a lady’s boudoir, a gentleman’s study and a children’s playroom. The presumption was that these provided retreats from a robust communal life, rather than a way for the family to lead solitary lives under the same roof. Miss Manners hears a lot about the new casual ways of living, and how much less stiff they are than the old ways. If anyone wants to debate this with her, she’ll be sitting in the pristine living room, hoping to see a friendly face.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – My husband and I reside in a modest, older home. Whenever one of his sisters comes to visit, she freely criticizes our home, comparing it to her new, lavish residence in another part of town.

On her last visit, she said, “This is such a little house. It’s hard to believe people actually live in such tiny homes.” I was so stunned by her remark that I could not think of a reply. I couldn’t decide if she was just ignorant, or if she was deliberately trying to hurt me. No matter her intent, I was hurt and angry. What could I have said to educate her and perhaps prevent such comments in the future?

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners recommends not wasting time on imagining a motivation for such awful remarks. Rather, she would suggest that you produce a sweetly pitying smile, and such kindly words as “Yet little houses can be full of happiness, as ours is. Perhaps that’s why we have never found it hard to believe that people would want to visit us in our little house.”

DEAR MISS MANNERS – The dining room and library of our home are on the ground floor and when we entertain, we often put several small tables in each. At the foot of the stairway opposite the library door is what is politely called the powder room. It is in full view of all coming down the stairs—and those seated in the library.

My wife feels it is “middle class morality” to keep the bathroom door closed when the room is not in use. While I agree that those on the bedroom level should be open, I think, as a matter of aesthetics, the fixtures on the dining level might best not be always in view. I advocate, in this case, leaving the door about four inches ajar to indicate availability in a less obvious way than if it were flung wide open. Will you comment on this disagreement?

GENTLE READER – Middle class morality? Oh, no. Anything but that! Miss Manners is aware that an accusation of practicing middle class morality is the deadliest of insults, but she has never understood why. Don’t all people identify themselves as being middle class, the rich to avoid arrogance and the poor to avoid pathos? Why would people be terrified of being caught practicing morality? Because it might ruin their reputations? Anyway, how does the bathroom door get to be a moral issue?

Miss Manners dearly hopes you are going to spare her the argument that privacy constitutes hypocrisy, but if that’s it, then you upper and lower class disdainers of morality should just take those bathroom doors off the hinges and watch one another. We hypocrites prefer other entertainment, and we especially do not enjoy dwelling on the connection between eating food and eliminating it. Furthermore, we are also resourceful enough to ask for a bathroom when we need one, and to knock on closed doors before entering.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I have relatives with young children who come to our home fairly often, and as soon as they arrive, they immediately scamper off to play in every room in the house. They feel as if it is their playground and their parents don’t say anything. After they leave, I find different things moved around. My husband and I have also had several people ask how much we paid for our new home. I think it is rude, but I do not want to lie, so for lack of a better answer, I tell them the truth. I don’t want to seem mean but I know I was not allowed such freedoms at ages 5 to 11. I do feel that at least our bedroom should be a private area and my only thought was to lock our bedroom door when they come over. Am I being too picky?

GENTLE READER – Too easily picked on, Miss Manners would say. You are allowing everybody to rummage at will through your house and mind, ceding territory as fast as anybody thoughtlessly claims it.

True, your friends could be more reticent, and it would be attractive for their children to hang back shyly in the absence of instructions. That may be out of your control, but if you could learn to reply to questions with a cheerful “Oh, I’m not going to tell,” and to announce to young guests “Let me show you the family room, where you can play,” you would find that all but outright louts will accept the boundaries you set. You don’t want those hanging around your nice new house, anyway.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – We would like to know how to handle an annoyance we are having with a friend. This woman will not allow anyone in her living room/dining room for any entertaining, to the point of having a fence in the doorways. These are not rooms with priceless antiques, although we are not dealing with unruly people or messy children. It has become such an insult to my husband that I think he will probably scale the fence and sit in the room alone, just as a matter of principle.

We are met at the front door, walked down the hallway to the kitchen, ushered to the family room. This has happened for weddings, funerals, Christmas, graduations, showers or any other occasion that may occur. The gates are explained as being barriers for the dogs, but the animals are usually kenneled at the time of company.

Is there some polite way we can make her aware of her rudeness? We realize she has the standard white carpet, but no one has manure on their feet or bib overalls from the barn.

GENTLE READER – Were you the only people banned from these sacred parlors, Miss Manners could understand how you could take offense. She would not permit you to occupy the territory by force, but she would acknowledge that you might not care to be entertained by someone who did not consider you worthy of her best.

What you have here is—how can Miss Manners put it politely?—a nut case. None of this lady’s friends seem to be worthy enough to use her best rooms, and no occasions—weddings, funerals—important enough. What is she waiting for?

Miss Manners recalls reading a short story about a similarly afflicted lady who was saving her best for an occasion so special that it never arrived in her lifetime. That lady was guarding the bed linens from her trousseau for a sufficiently important occasion, her own wedding apparently not qualifying. Finally, she was no longer able to protect the now-crumbling sheets, and they were used—as her shroud. There seems to be a moral here about enjoying things while you can, and sharing them with people you care about. There is no way for you to “handle” someone else’s peculiarity, except to share Miss Manners’ hope that your friend allows herself to tiptoe into the rooms when no one else is around and to eke what pleasure she can out of having white rugs.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I once returned from college to find my old bedroom painted pink and my sister’s things firmly planted in it. I turned and opened the door to the guest room—there were my things, in much better order than I had left them. I felt kind of bad, but I certainly didn’t argue. It wasn’t my house.

My sister is gone again, married now, and I’ve made my return as she did, except with my husband. Domestic issues are not a problem as long as we remember who owns the house and give respect and deference where it is due. (No, we didn’t get my old room back.)

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners hopes that you realize that you have seriously violated a tradition of family life. When parents so much as replace a chair in the room of a child who has moved away, even if it was years ago and the child has his or her own house twice the size, custom requires that it set off an emotional rampage.

Not having a permanent shrine is considered the basis for fruitful family discussions, such as “I bet you were glad to get rid of me” and “You always did love her more.” Miss Manners congratulates you on forgoing this opportunity. By conceding that your family should enjoy the extra room, you have also made room in your psyche for more interesting topics.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I live in a security building which contains eight apartments. When guests arrive, they must first ring my apartment from the front door. I may then use the intercom system to allow the guests to announce themselves, and then electronically unlock the entrance from my apartment. This seems to be somewhat inhospitable, as the guests must then see their way up a flight of stairs and through a series of doors. Should I be greeting them at the door, and saving the intercom for package deliveries?

GENTLE READER – While appreciating your hospitable intentions, Miss Manners believes it superfluous for you to greet your guests in the lobby. (It is even considered a politeness, for those who have the luxury of a household employee to open the door, to allow guests to collect themselves and smooth the ravages of the weather before being greeted by their hosts.)

This is not to say that you want them stumbling about the building. You have an intercommunications system, so use it to say a pleasant word of greeting and give your guests instructions. In these circumstances, it would be a hospitable gesture to be waiting at your open apartment door when they arrive.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – In the communal parts of the house (kitchen, living room, dining room, family room), when is it proper to initiate a private conversation between two people when three or more are in the room? If it’s not, why not? What is the polite way to arrange or initiate a private conversation? If one walks in on a private conversation, what is the proper way to proceed?

GENTLE READER – Technically, one never holds a conversation that excludes one or more persons within conversational range. That said, Miss Manners is as aware as you that a household in which every exchange had to be broadened to include everyone who happens to be in the room would be seething with enough unexpressed tensions to cook the roast without benefit of microwave.

The polite method of securing privacy for a two-person conversation in a three or more person household, other than waiting for the unwanted people to walk the dog, is to change the venue. Three people are in the living room, and one says to another, “I need to talk to you,” whereupon they repair to the kitchen.

Should someone walk in on a private conversation already taking place, the people holding it may indicate what is going on by saying “Would you excuse us? We’ll come join you in a minute.” It is not rude to admit to the need for privacy, although a polite excuse, such as “This is not something that you would be interested in” or “We’re having a father-daughter talk,” takes the edge off its exclusionary nature.

Miss Manners recognizes that there are times, such as family dinner, when a brief private exchange can’t wait, and yet leaving would disrupt the occasion. Two people exchanging significant glances do so at their own risk. Two children rolling their eyes as a commentary on their parents’ remarks should make sure they are not caught.

Parents, on the other hand, have a privilege not politely available to children. If they speak a foreign language that the children do not know, they are permitted to exchange a few words in that language. The excuse is educational: Many a child has been encouraged to study with the motivation of finding out what the adults are saying.

This privilege does not apply to children, especially if the language is pig Latin. Miss Manners has never bought the argument that parents are allowed no privileges they don’t democratically share with the children.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – We are four graduate students of both sexes sharing a large house in a university town. One of us owns the house, but other than collecting the rent, does not claim any special privileges. Each of us has a private bedroom, but the kitchen, living room, and dining room are shared equally.

One of us hosted a stand-around-and-chat sort of a party—with music and snacks, vaguely like a cocktail party, except that no alcohol was served; dress very casual—without inviting any of the residents of the house. One, in particular, was miffed. They are members of the same organization and consequently have many of the same friends, although she does not belong to the sub-group that was being entertained. She did not like the idea of being compelled to leave the house for the evening, or lock herself in her room, so that a group of her friends could gather in her living room, but—believing that there is no proper way to complain to a hostess for failing to invite one to a party—has not discussed this. Their relationship has cooled to a point which can only be described as arctic.

The following week, the same housemate had a potluck dinner party in the house, not inviting any of the other residents but chattering on about the special delicacy she was going to contribute which we would have the opportunity to try because there probably would be leftovers. Other residents of the house probably would have declined if invited, but perhaps should have been invited anyway.

Left unanswered is the question of whether the one who knew them was excluded to allow the groups privacy in which to reminisce, or to keep her from feeling left out while listening to their conversation. If the latter, I think she should have been invited and allowed to decide for herself whether she would feel so uncomfortable that it would be better to decline the invitation. If the former, I think the groups should have found other places for their parties.

I have on occasion “invited” housemates by saying “I would love to have you, but I am afraid you might be bored.” This often results in the housemate declining without feeling slighted. Of course, sometimes the housemate accepts. The keys to making this work are being (or seeming) sincere in wanting the housemate’s company if s/he is willing to sacrifice an evening to attend the potentially boring event, and treating the housemate as a welcome participant in the activity if the invitation is accepted.

Personally, I would never dream of giving any sort of a party in any private home without inviting everyone who lived there, whether permanently or as a house guest. I can’t think of a polite way to state or imply the message: “I would like to have a party in your home, but I think the party would be improved by your absence, so find somewhere else to go that evening.” I know my practice is acceptable, but is it required?

GENTLE READER – Is this a rooming group or a group marriage?

Wait. Miss Manners would like to withdraw that question—but not because it sounds like a more interesting inquiry than she intended. It is the wrong question because even members of a happy family should occasionally be able to entertain their own guests at home without including the entire household. No one is supposed to sulk if not invited to be a fifth at bridge, so to speak.

By definition, people who live together already like one another (Miss Manners is tactfully ignoring those who are plotting escape), and therefore the issue is one of using rooms rather than misusing feelings. Although your bit about improving the party through someone’s absence is indeed an unfortunate one, Miss Manners can think of a way of saying the same thing politely: “Does anyone mind if I use the downstairs on Tuesday to have some people over?”

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Is there a rule to follow regarding the use of washers and dryers in apartment building laundry rooms? If someone else has left clothes in the washer and the cycle is completed, is it permissible to remove the clothes? Or must you wait until that person comes to retrieve them? What about the dryer? If it is OK to remove the clothes, should you fold them?

Sometimes people leave things in machines a long time, and it is extremely difficult to keep coming back to check (not to mention the fact that someone else may cut in ahead of you then). At the same time, I feel uncomfortable about unloading people’s clothes, much less folding them. I don’t mind doing it, but I feel like I’m invading their privacy, if you know what I mean.

Personally, if I am delayed, I am glad if the next person goes ahead and takes the clothes out, because I am not intending to inconvenience them. But needless to say, not everyone may feel the way I do.

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners prefers not to pursue the avenue of inquiry suggesting what inroads one makes into another person’s privacy by folding that person’s laundry. For the sake of convention, polite people consider other people’s wash to be invisible, whether it is hanging on a line or sitting in a puddle in the machine. However, this should not prevent other people from using the machines. Provided the laundry is handled in such a way as not to make doing it again necessary, it may be put aside by anyone wanting to use the machine.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Following a shower, does a person step out of the tub to dry, or stay in? For the second, less water ends up on the floor, yet it seems like bathroom floors are built to take water. Please clear this up for my brother and me by giving us the correct bathing etiquette.

GENTLE READER – The correct bathing etiquette is that you do not invite Miss Manners to join you in the shower. Manners require that you leave the bathroom floor dry for the next person. How you manage this is up to you. Acts performed alone are outside the jurisdiction of etiquette, which ought to make you as grateful as it does Miss Manners.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – My boyfriend and I went to visit some friends for the weekend, and upon our arrival, we both had to use the facilities. Having had more coffee than I, my boyfriend used the washroom ahead of me. Later that evening, I took him aside and reminded him to be careful not to leave the toilet seat up, as he had earlier. I told him that I thought it rude. Not wanting to be an ignorant guest, he made a conscious effort to put the lid down for the rest of the weekend. Subject dropped.

But whenever he is in my apartment, he leaves the lid up and it irritates me. He knows this bothers me and we argued over whether a guy should put the lid back or not. He says that he does half the work by raising it, and I should do my share by lowering it. I guess I’d really be overworking him if I asked him to put both lids down!

What is the etiquette of the toilet? Does it matter whose house you are in, a male’s or a female’s? I can live with this idiosyncrasy if I’m just being overly picky, but need to know what is right.

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners hopes you are not thinking of marrying this gentleman. Aside from the fact that he tires so easily, he has a peculiar sense of etiquette. It is not toilet etiquette to which she is referring, although both toilet lids do belong down. (That way, to enter your unappetizing argument, you both have lifting and lowering to do, although he will be dealing with the double weight of two lids.) What about the etiquette of intimacy? Don’t you wonder why he continues a practice that—regardless of any arguments about fairness—he knows annoys you, when he is willing to be considerate of others?

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I live in a housing development with a communal pool—a very large lap pool, although no ropes are provided to mark off individual lanes. The pool is seldom crowded, so lap swimmers (I swim laps nearly every day) and casual bathers seldom have problems sharing. However, during school vacations, the pool becomes very popular with children and teenagers who frequently get in my way and sometimes crash right into me. I take great pains to avoid them, but to no avail.

Even when the pool is far from crowded, if I start to swim in a vacant section, within minutes there will be roughhousing youngsters blocking my lane. Since most of these children are old enough to swim without adult supervision, there is no parental authority to which I can appeal. My polite requests that they try to be more courteous of other swimmers are seldom heeded. Outright scolding sometimes works, but seems awfully harsh. After all, I do not want to spoil their fun or squelch their high spirits. I just want to swim in peace.

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners is glad that you recognize that full-scale naval battles do not fit into swimming pools. As you point out, the children are not purposely annoying you, but merely enjoying a different kind of fun in the pool.

What they need is not scolding but rules, and reminders about rules. In a communal pool, you cannot make rules unilaterally, but you can appeal to managers and other tenants to draw up rules that will allow everyone to enjoy the pool. If separating the lanes does not work, perhaps regulating the hours by activities will.

Technically, newspapers, magazines and books may be the individually owned property of the person who ordered them. This does not alter Miss Manners’ belief that any collection of people—be they roommates or family—who share the same living quarters and yet have no desire constantly to share what they have learned from reading is doomed.

A gentleman of her acquaintance once complained to her that he was sinking under the number of his lady’s favorite books that had arrived following his declaration of love. “Have you ever heard of a romance that had a reading list?” he demanded. Miss Manners replied that she had never heard of one that hadn’t.

Nevertheless, a household where people cannot find their own reading material in readable condition is also doomed. In practical terms, this means:

First rights over a household newspaper belong to the person who gets up first, and then makes the supreme effort of fetching it. Reasonable generosity is nevertheless mandated. A considerate early riser would, for example, hand over any sections not immediately being read. A clever early riser would quickly read the sections not of great interest before the first footsteps are heard, and reserve the most satisfactory ones. Miss Manners has had to agree that the first reader may also reserve any sections which contain the continuation of any story in the section he or she is actually reading. She only notes that this necessity has led her to the suspicion that newspapers with the policy of jumping stories from one section to the next must be anti-family.

The advantage of early rising is not confined to first choice. It allows the privilege of announcing the news—but that privilege also carries its etiquette obligations. Frightening exclamations (“Oh, no!” “Guess what?” “You won’t believe this!”) are strictly rationed. Using them as an excuse to read off all the headlines is an irritating habit, leading to domestic mayhem. But then, so is whistling or laughing provocatively, and then not saying anything until the other person is forced to ask “What? What? What?” Indeed, there is a responsibility to alert others to items that may be presumed to be of interest to them, without skimming off the pleasure of reading them. It is a service to summarize information that others should know but that no one enjoys reading. This is a delicate balance, but no one ever said that sharing a household was easy.

Readable condition means that the first reader of the paper—indeed, all but the last reader—may not tear articles out, spill coffee, trail it in the bathwater or, without prior agreement, do puzzles. It also means refolding the paper the way it came.

Magazines differ in that the pleasure of first reading (not to mention that of tearing off the plastic wrapper and disposing of the little subscription cards among the pages) belongs to the subscriber, not the first person to spot an issue in the mail. The subscriber also gets first choice at clipping, sniffing perfume advertisements and filling out reader surveys, but is otherwise expected to share.

New books are at the disposal of their owners or prospective owners (meaning that you can’t leave fingerprints in a book you plan to give as a present); a household book remains in the domain of the person who is reading it—even when that person has gone off temporarily and left it.

Of all reading skills, the greatest of all is the ability to interest another person in the book one is reading oneself, without inciting hostility—from either boredom or the hope of snatching the book away.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Please advise if there are guidelines regarding reading while occupying the bathroom.

GENTLE READER—Well, let’s see. Miss Manners hadn’t thought about it, but there must be some.

Don’t drop a library book into the bathtub.

Don’t pretend to be so engrossed that you can’t hear another member of the household delicately inquiring whether you are going to be in there all day.

Don’t use dental floss as a bookmark if anyone else is ever going to read the book.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I live in a house with three roommates. We are all good friends and all college students. Three of the four have televisions in our own rooms. Recently, two of us decided to get cable television installed; the other two did not. The two of us split the cable bill.

In the beginning, when there was a good movie on, my room turned into a movie theater, and it was a lot of fun to get together like that. But now when I come home from classes, one of the two without cable is always in my room watching. I see them getting ready to jump into my room when I go out to study. The inconvenience is not their being in my room—it’s that neither of them has had the courtesy to offer to pitch in a little each month. Were I in a better financial situation, it would be no problem. I’m not even asking that we all split the cost equally, but a few dollars would help. The problem is that I don’t know how to ask. If I did, I’m sure they would respond, “I don’t watch that much.” And believe me, they do.

GENTLE READER – It is a basic requirement of roommatehood to be able to talk frankly about splitting costs, chores and privileges. It seems to Miss Manners that the proper way of asking is to say “Hey, I don’t mind your being in my room so much, but could you help with the cable costs since you like to watch?” Considering the answer you anticipate, the time to do this is at the end of a long session of television watching.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – After realizing that there is no right time to tell your parents that their child is gay, I finally did it, and somehow we’ve all managed to survive. They don’t fully understand, but we’re at least communicating. I have also informed siblings, relatives and close friends about my sexual orientation, because I didn’t want them to hear about it from a third party. As a result of all this “sharing,” I’ve found most people to be supportive and many of my relationships have grown even closer.

What this is all leading to is that I’ve recently moved into an apartment with several other people whom I’ve known for a couple of years, but not really well. Should I sit each person down as I did with family and close friends, or leave a gay newspaper on the coffee table and see what happens? Am I setting things up for an explosive situation, or am I over-reacting?

If they do ask, I plan to say yes, I’m gay, and ask if they want to talk about it. If they’re not thrilled with this, I plan to tell them that I don’t have time to deal with their sexual insecurities and walk away. The worst thing that could happen is they would ask me to move, and honestly, that wouldn’t be the end of the world. I just want to live in a situation in which I can be fully open about my sexuality.

GENTLE READER – To allow people to find out that you are gay, even to make sure they find out by the newspaper ploy you suggest, is one thing. Roommates generally know what one another’s social lives are like, and you don’t want to have to hide yours. But to invite people to talk it over is to invite them to offer opinions on a matter which is none of their concern. Their approval would be as patronizing as their disapproval would be distressing.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – As the resident of a large condo building, I have often wondered as to the correctness of sticking notes and/or cards in doorjambs. Some notes I can understand—“Alice, call me when you return”—although I feel they should be in an envelope, not just hanging out for all to read. But what about cards, and thank you notes, and invitations? Does propriety dictate that they be mailed?

We have a woman living here who will write on anything and tape it to a door. I once came home to find a paper plate taped to my door, and another time, a shoe box lid.

GENTLE READER – Propriety does not get a cut from the Post Office; a hand-delivered letter may be every bit as formal as one that is mailed. As a matter of fact, sending your footman around with a letter is even more formal than posting it, even if today’s footman wears nothing but jogging shorts and works for a bicycle delivery service.

So the issues here are what the letter is written on, and where it is left. Shoe box lids and paper plates are not what you would call formal. You should not write your wedding invitations on them. In fact, Miss Manners is hard pressed to think of anything that is sufficiently informal for their proper use.

And while it has become commonplace for college students to hang message boards on their dormitory room doors, for the convenience of people making appointments or delivering witticisms, open communication is not quite proper in a grown-up apartment building. It may also be dangerous, as it alerts strangers to the fact that the occupant is not at home. How much extra effort does it take merely to slip a note under the door, rather than to tape it up?

Some people now want to practice etiquette in the original sense of the word, and Miss Manners is alarmed. She remembers those dear old days at the 17th-century court of Versailles, and she doesn’t want them back. Codes of civilized behavior are far older than that, of course; by definition, they date back to the beginning of civilization. Miss Manners would be only too glad to see ours put back into practice. She is happy to explain its rules upon request, and to amend or prod them now and then, so that they keep up with the times.

Louis XIV went too far with his habit of continually posting arbitrary new written rules of behavior—not just for soldiers, as had been customary, but for everyone else within his purview. Hence we are stuck with that odd word “etiquette,” a version of the French word for those pesky stickers. And stuck with the idea that one can keep making up new rules, posting them on the walls and expecting everyone else to jump to obey.

A lot has happened since this practice was introduced, such as the French Revolution and the Enlightenment, and now citizens are doing this in their own homes. Above a typical “Welcome” mat, the front door may announce “Wipe Your Feet”; inside, the living room may bark “No Smoking”; and the bathroom admonish you to “Clean Up After Yourself.” The television room might have one sign about putting the remote control back and another about rewinding videotapes. Various doors may be marked “Quiet,” “Sleeping,” “Please Knock” and “Keep Out.” Some signs are written in pleading tones (“Please Think of Others”) and some in hostile ones (“I Am Not Your Maid”). The only sign missing is “Post No Bills.”

Miss Manners has been wondering what is going on here, apart from the habit of snitching public signs and bringing them home for souvenirs. It seems to her that it is something more than the peculiar inclination people now have for displaying their sentiments, witticisms, affiliations and brand loyalties on their bodies.

These are instructions, and they are seriously meant. The motivation seems to be the same as that at the French court: to get people to follow the rules. But Louis XIV was not what we call a great role model. It’s not just that he thought it was funny to plant hairs in a lady’s food because she was so affected that she ate with a fork instead of with fingers, as he did. He kept setting and changing rules as a power play, which is not a proper function of etiquette, even if he did give that noble concept its name.

Miss Manners understands that the citizens who are now imitating him have more benign motives. They want to be able to set the rules in their own houses—but not because they are tyrants who like to keep everyone frightened of doing something wrong. The rules they post are, with few exceptions, reasonable ones that every civilized person would agree upon to maintain a pleasant atmosphere for all. However, in order to do this, they sacrifice the atmosphere with stern and unsightly signs. Why would a society that considers billboards to be eyesores want to live among them?

All of this is an argument for the teaching of etiquette, so that everyone in the society knows that it is not nice to leave a mess in the sink or make a racket when someone is trying to sleep. Meanwhile, however, the house is full of people who don’t know what to do without explicit commands. If they are your children, you teach them, by example, word of mouth and as much nagging as you can get in until they leave home. If they are roommates, you work out an agreement about the rules. If it is someone who professes to love you, you say “I know it doesn’t seem important to you, but it is to me, so would you, darling, please, for my sake?” If they are guests, you use symbols (the absence of ashtrays means “No Smoking”; closed doors mean privacy) or requests disguised as apologies or helpfulness (“Oh, dear, I’m afraid it’s so messy out; just stay there a second while you wipe your feet and I’ll get you a towel”). The stubbornly rude guest doesn’t need a sign, because he won’t obey it. All he needs is one stroke of the pen—through his name in your address book.

To go into someone’s home and then roll your eyes, whisper comments on the decor or report afterwards to others that it is in terrible taste is rude. So much for the spring house tour.

Miss Manners admires the selflessness of those whose charitable impulses lead them to open their premises to uncharitable remarks. For every “Isn’t this lovely!” there is always a full chorus repeating “I’d go crazy if I lived here,” “That couldn’t possibly be real” and “Will you look at that?” Taste being taste, nothing is going to meet everyone’s standard.

So we have a strict (and unenforceable) rule against guests’ talking about their hosts’ possessions. “Commenting on one’s things,” it is witheringly called by those who maintain the old-fashioned sniffiness of believing compliments to be as impertinent as insults. The thinking is that hospitality does not confer the right of appraisal, so even approval is out. Also that in the natural course of events, people live in an accumulation of stuff from previous generations, not to mention that awful stuff introduced by the subsequent generation in residence, so they should receive neither credit nor blame for the effect.

Modern hosts have suspended at least half of the evaluation rule. If they put a lot of work and/or money into their surroundings, they are eager to produce a burst of admiration. Sometimes they stimulate this by pointing out new possessions or offering tours.

Perhaps it seems hard on guests to be required to produce compliments, as indeed they are if prodded, and still to be barred from divulging any other opinions once they are safely outside. Miss Manners expects them to manage it anyway. She sets an example by unswervingly believing that everybody who wants to live in a place characterized by quiet good taste does. As far as she knows, that notion, or perhaps delusion, applies to just everyone who doesn’t live in a fraternity house.

It is possible that more than kindness is involved in her reluctance to issue edicts declaring what is good taste in the way of household furnishings and what is not. Many of her distinguished predecessors unfortunately went on record declaring that everything Victorian—the very adorable look so warmly cherished now—was horrible beyond belief. Dear Edith Wharton loathed the style for which her name is now admiringly invoked, jammed with her once-distinctive preferences into the trunk of history.

THE HOUSEHOLD SHRINE: The urge to celebrate oneself is best indulged at home, but even there it must yield to the rule against boring others senseless. Souvenirs of triumph should therefore be confined to bedroom, bathroom or study, with tours and explanations offered only upon request and with occasional pauses in the narrative to allow escape.

Still, Miss Manners thinks it useful to mention a few checkpoints associated with household taste. One might consider them when judging one’s own house, since she has forbidden judging anyone else’s.

Shrines to oneself should be displayed discreetly. Award statues may be used as doorstops, plaques and diplomas can be hung in the kitchen or bathroom, but your wedding portrait goes in the bedroom, the mounted fish you caught goes in the study and photographs taken with the Vice President or a movie star must be placed in shelved albums—not even albums left on coffee tables.

Nothing should seem permanently roped off. You may tell the children to play where there is less to break, and you may refrain from using your grandmother’s china to feed those louts who constitute the immediate family, but everything should be used sometime. It is insulting to maintain rooms or objects that you consider too good for anyone you know to use.

Things should either be what they are supposed to be or miss by so much that there is no possibility of confusion. This is why real flowers are fine, china flowers are fine, but artfully done plastic or cloth ones are not.

Objects left visible in a bathroom should not be surprising or distasteful to anyone else, housemate or guest, who may need to use that bathroom.

Table space and chairs must be provided for anyone who is asked to eat anything more serious than a cucumber sandwich.

Finally, it is in bad taste to have a house in perfect taste. It screams of having excluded all sentiment in the form of leavings or offerings from others.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I want to know if one must have just one theme in a room and/or house to be correct? I have nautical bathrooms, blue and white dishes in kitchen and library, and the living room is decorated mainly with florals, sea/ship/lighthouse pictures, but I just got two Egyptian drawings I want to put in there. I know it should reflect our interests but don’t want to do anything too drastic.

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners trusts that you understand that she is not the decorator. There is indeed an etiquette aspect to the question you ask, but it has nothing to do with helping you achieve a fashionable look. On the contrary, etiquette is wary of anything too fashionable or too consistently anything.

In the matter of household decor, it just doesn’t consider aesthetic pleasure to be worth the price of banning things of emotional value—discoveries, legacies, children’s art, presents and such—because they don’t fit in. Presumably what you have there is a house, not a ship or a theme restaurant.

Modern couples have no trouble explaining, in a tone of high morality, why they consider it important to live together before deciding whether to marry: They get an idea of how they feel about each other apart from the artificial circumstances of going out; they see what the other person is like when not on his or her best behavior; they see if their daily moods and habits are compatible—and so on. Anyone with children past the dinosaur stage is familiar with this argument. As most parents do not wish to be considered in the dinosaur stage themselves, they pretend to agree, and say nothing about what people who live together before marriage miss out on when they marry:

The trousseau.

Didn’t think of that, did you, you impetuous young things, you?

Don’t tell Miss Manners that love is more important than dry goods. If you feel that way, why do you spend your official engagement period hysterically evaluating every known pattern of china, silver and trash compactor? (Come to think of it, why do you go after all that good stuff at all—and forever afterwards entertain your friends using paper plates and drinks in their original bottles and cans?)

Even the most tolerant parents could not keep a straight face if a modern bride attempted the traditional announcement that she really must have a fortune’s worth of intimate lace because she would be embarrassed to have the bridegroom see her in her old things. He has probably been seeing her wearing his old things.

However, bridal couples do get away with asking for a trousseau of silver, china and crystal usually, Miss Manners regrets to say, from their wedding guests—and with the cheeky excuse that they are only anticipating what agonies these people would otherwise suffer in not knowing how to please them.

However such goods are now acquired, here is a traditional starter set of household goods.

Every new couple needs fine china in order to feed the traditional marital argument about whether or not it may safely be washed in the dishwasher. There should be at least one extra of each item, so as to soften the agony (and the instinct to cast blame) at the first sign of a chip. Otherwise, only as many dinner plates are needed as there are dining room chairs—presuming that when bridge chairs and other improvised seating is needed, there will be plates in two patterns, one of them borrowed. When dinner plates are asked to do extra duty—for example, in place of a cake stand—they do it with bad grace and drip icing over the side, so some platters are needed. The real workers are eight-inch plates, which are used alone for breakfast, luncheon and tea, and at dinner for first courses, salad and dessert, so there should be either a lot of them or a fast hand with the suds in the kitchen. One also needs five- or six-inch plates for bread and butter and fruit, and to serve as underliners; and bowls, which get up early to do cereal and stay up late for informal soups (grand soups are served in rimmed plates at dinner, or double-handled cups for lunch) and runny desserts.

Specialized glasses for each type of drink hardly exist any longer. It must have been that last earthquake that made people who used to have special glasses for hock, claret and Rhine wine decide, Oh, the heck with it. Just about everybody is down to two sizes of wine glasses (for red and white, or for sippers and guzzlers), with stemmed water glasses and tulip champagne glasses for the festive table (Miss Manners misses sherry glasses to go with the soup course) and unstemmed large glasses (short for whiskey or juice, long for cocktails, diet soda or milk).

Don’t get Miss Manners started on silver. Confirming everyone’s worst fears about etiquette as a trap for the unwary, she goes in for all the excesses of the Victorian imagination—terrapin forks, breakfast knives, berry spoons, asparagus tongs, strawberry forks, orange knives, marrow spoons, ramekin forks, chocolate muddlers, pastry forks, sherbet spoons and so on. What a normal person needs are dinner knives, forks and large oval spoons (not teaspoons) for soup and dessert; a smaller-sized knife and fork for salad, fish and breakfast; a teaspoon for tea or a demitasse spoon for after-dinner coffee.

There also used to be a linen department to the trousseau, consisting of white damask tablecloths with flag-sized napkins and mats with smaller napkins for daytime meals only, six complete changes for every bed and dainty guest towels for the guests to ignore while looking for the family towels to wipe their hands on. The presumption was that no decent person used paper napkins, put bedsheets on a table or considered a bed to be made when covered with something huge and lumpy, other than the family dog. Also that people made their beds before they slept in them. So you see that the trousseau really is an old-fashioned idea.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – My sister and I are having a war over borrowing and lending and desperately need your insight to settle our disagreement.

I believe that when someone borrows something it is their responsibility to:

1. Pick it up

2. Take good care of it

3. Only keep it for a reasonable length of time

4. Arrange for its return

Well here’s the story: My sister asked to borrow a VCR tape that I had recently purchased. Since I’m at her house frequently, I delivered it. About two weeks later, I asked her if she had watched it, which she had, and might I have it returned to me.

At that point she told me that she had allowed her next door neighbor to borrow it and that she would get it back as soon as possible. Another week passed when I asked again for the return of my property at which time she had a fit.

Her fit isn’t important, but am I correct in saying that she is in violation of good manners in that she loaned something that wasn’t hers (without my knowledge) and she kept it far too long. My video store considers one night long enough for its newest releases and five nights for the next level. My sister was way past that point!

GENTLE READER – Your sister has lower standards than your video store? My, you do have trouble.

Miss Manners doesn’t condone your sister’s behavior, but she doesn’t understand yours, either. Surely you have a long history of your sister’s claiming your sweaters, books, lipsticks, scissors, perhaps even beaux, and returning them late and damaged, if she returned them at all.

One should never again lend one’s belongings to someone who has violated the rules you listed, and certainly not to someone who then produces rude fits (which may not matter to you, but which matter more to Miss Manners than all your rules put together). What you should offer her is a polite refusal—“No, I’m sorry, I’m going to need it”—without leaving yourself open to argument.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – How can I tactfully get friends to return books that I have loaned them?

GENTLE READER – By continuing to do what you intended when you lent those books to friends—urging them to read them. Every chance you get, you should ask whether your friend has read that wonderful book yet. It shouldn’t take more than two or three times before the friend starts telling you how terribly busy he is—overworked, with a lot of other reading to do, and so on. At that point you say, “Why don’t I take it back, then, and lend it to you again when you have time?” Miss Manners promises that your friend will be as happy to be rid of it as ever he was to borrow it.

If rampant consumerism is vulgar, as everyone at the mall agrees it is, there remains a respectable way to have fun with dry goods. The basic idea is the same, but in the opposite direction: Instead of acquiring things, you get rid of them.

Unless this involves leaving refrigerators on the sidewalk or piling empty bottles in the neighbors’ trash, you can get a lot of moral credit for disposal, Miss Manners has noticed. If you give things away, you are an angel of charity; if you throw them away, you are at least a good housekeeper. Also, it costs less than shopping.

One might think it would cost nothing at all, but that is not quite the case. Those who get into the spirit, merrily pitching anything they can get their hands on, occasionally find themselves shamefacedly obliged to run out and replace what they may have pitched prematurely. Such as sections of the morning newspaper that other people haven’t finished reading, even though breakfast is almost over.

This brings up the sad fact that there is also a moral onus on getting rid of things. One might expect it to be directed towards those who preach the joys of being free of materialistic ties, especially while heavily dependent on the generosity of those to whom they are bragging. What astonishes Miss Manners is that even modest folk are attacked if they confess to enjoying a good sweep.

Aside from unpleasant personal comments, they will be challenged on allegedly practical grounds:

1. I haven’t finished with that yet.

This may be perfectly true, in so far as it goes. What is left unsaid is that it is clear when something is never going to be finished—the jigsaw puzzle that has been occupying the dining room table since Christmas, the tools on the floor near where there has been talk of building a shelf, the magazine that has been on the bathtub ledge for a week.

2. I might need it for reference.

But you won’t be able to find it, anyway. That’s why we have libraries and all that information on the Internet.

3. You can’t throw out books!

No, but you can donate the duplicates of good books to schools and the terrible ones to neighborhood book sales. Hard as it is to believe that anyone will ever want to read another book about how to love oneself or lose weight without feeling deprived, someone always does.

4. We need the box in case we have to send it back.

But you won’t be able to find the warranty, and by the time you do, it will have run out. The thrift involved in saving containers has to be weighed against the extravagance of allowing them large portions of living space, sometimes enough to sublet.

5. If anything breaks, we’ll be glad to have a spare.

The traditional way to refurnish was to wait until a piece of furniture fell apart and then go foraging around for replacements kindly left by ancestors, but this presumed a castle with infinite storage, in which good furniture had the grace to turn itself quietly into antiques. That you will want to cannibalize the defunct electric toothbrush for parts if the newer one breaks is not a likely scenario.

6. We don’t want it, but we’re keeping it in case someone else in the family might.

You might ask them. Otherwise, this holds only for people with children who can be expected to set up residence elsewhere (from their parents or present spouses) within the next few years. Even then, they often prefer to buy other people’s cast-off furniture from the same place to which you could donate yours.

7. Those things are going to be worth a fortune someday.

Whoever created the market for old comic books has a lot to answer for. The formula that junk plus patience equals a fortune is believed only by those who haven’t been around long enough to observe otherwise.

8. It’s bound to come back into style.

Here, Miss Manners weakens, because indeed it might. This is justification for keeping things one truly loves, although not what is perfectly good because it has never been worn.

9. It would break my heart to part with it.

Here, she really breaks down. Yes, you should keep dolls, stuffed animals, wedding dresses and letters. There are a lot of superfluous things in every household, but a heart is not one of them.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Recently a friend of mine gave me an olive green lamp with a tasseled shade as a house warming gift. I tried putting it in numerous places in my house, but wherever it is, it sticks out terribly. I value her friendship and I don’t want to insult her, but I can’t stand the sight of this lamp. What should I do?

GENTLE READER – Flag your friend’s name in your appointment book with the note “Green lamp,” reminding you to get the awful thing out of the closet before she visits. Miss Manners promises you that you don’t have to do this forever.

Once given, a present goes out of the jurisdiction of the donor, who is not supposed to notice, let alone inquire about, what happened to it. Nevertheless, it would be kind to have it around for a while before disposing of it. The only strict requirement of etiquette on your part is to make sure that you do that in a manner not likely to come to your friend’s attention. No lawn sales if she lives in your neighborhood.

“The napkins quickly became the event’s treasured stuff-in-your-purse souvenir,” stated the glossy report of a swish gala taking place in what is now defined as society. That is to say, the event was a dinner dance given to honor a designer of the sort of clothes one needs to have if one attends dinner dances in honor of designers of the sort of clothes one needs to have, and so on. Miss Manners has always been in awe of this world as a perfectly self-contained economic system.

She admits to being startled that public commentary, written in an unmistakably admiring tone, noted that the guests were stealing the napkins. An accompanying photograph showed an untouched place setting, still with its fine cloth napkin, especially embroidered with the theme of the occasion.

Is this how people are furnishing their houses? No doubt it is an economical way of doing so, but people who try to justify it actually do so in terms of sentiment.

In this case, the napkin was identified in the caption as a “hot dinner item,” and Miss Manners has always understood hot items to be goods offered for sale from the back of trucks by suspicious-looking characters who seem to be in a pressing hurry to complete the transaction. She was startled by its referring to items swiped by expensively costumed people out to do honor to someone they admire. If pilfering were, indeed, the activity of the evening, doesn’t the information belong in a police report, rather than in society news?

Not that Miss Manners means to quibble about what is or is not society. Surely the commercial world has a larger interest in prosecuting shoplifting than the world of mere play. Is it possible that this is what its distinguished members do to one another on their stylish outings? If not, or at least if everybody present was not involved, haven’t any innocents among the smiling people pictured been insulted, if not libeled?

What shocks Miss Manners most is that she suffers all this debilitating shock alone. Helping oneself to the fixtures now seems to be considered respectable, provided it can be classified as collecting souvenirs.

There is another word that has had to be redefined for Miss Manners in its modern sense: “souvenirs.” She used to think it meant objects that travelers bought when driven to distraction by airport boredom and the realization of being short one present. She could think of no other way of accounting for the idea that snow scenes of state capitols make coveted paperweights. “Souvenir” has now gone back to its earlier meaning of being a keepsake to stimulate the memory. What’s more, memories are in dire need of help, judging from the photographing, recording and grabbing that goes on all the time now. It seems to Miss Manners that most fancy occasions now suffer from the Heisenberg Effect: The festivities themselves are significantly altered, not to mention obliterated, by the rush to record them.

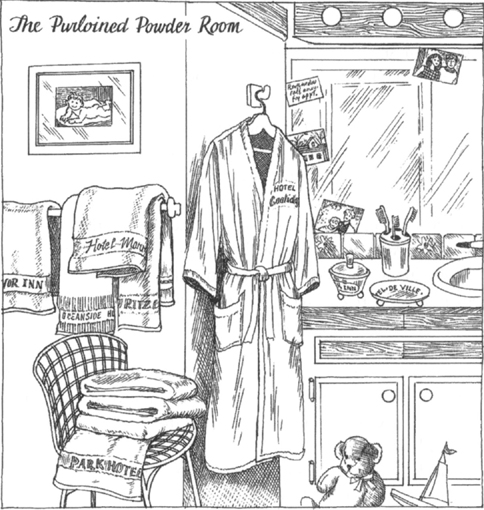

She understands that there is also a tremendous interest in owning artifacts that will remind people of the hotel rooms in which they have stayed. Once that meant lifting ashtrays. Now television sets and lamps are the souvenirs of choice, but the problem of packing them has led travelers to settle for the paltry toiletries that canny hotels offer as a lure to keep them away from larger heists. Miss Manners once made a laughingstock of herself by confessing that she thought these goods were just to be used while occupying the room, and was insulted by the notion that they were there to satisfy her presumed appetite for theft. Still, she cannot imagine that all ball-goers feel that they have been invited to steal the tableware.

ACQUIRED TASTE: Although off-the-budget décor is a popular method of suggesting worldliness, stealing is not an approved method of furnishing a household. Those not impressed by the moral angle might consider that their children and guests may be sufficiently in agreement to take up the implied offer.

Come to think of it, the honest ones may have been the ones who took the napkins—to put over their faces so as not to be mistaken for anyone who might have taken the forks instead.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – My grandparents have a desk that I would like. I do not want to hurt their feelings or be pushy or rude. Is it all right to ask for the desk now while they’re alive, or ask if they put it in their will that the desk be given to me?

I do not want to embarrass my mother—or myself. My mother is an only child, so she will probably be in charge of their estate, but I do not want to ask her for fear of hurting her feelings.

If this is totally out of line, please tell me so. My grandparents are in their early 90’s. I have admired this desk ever since I was a little girl.

GENTLE READER – Yes, this is totally out of line. There is no polite way to make cheerful plans with people that, in order to be realized, involve their being dead.

What you can do, if you promise Miss Manners not to be obvious about it, is to admire the desk. You can tell your grandparents and your mother that you have loved it since you were a child, and hope that this will encourage them to think that you should inherit it. When your grandparents actually are dead and their property is being dispersed, you may ask your mother, as executrix, if she would be willing to let you have the desk, which you would cherish in their memory. Miss Manners hopes this will be a long time from now, as grandparents are harder to come by than desks.

Showing off is bad manners, as every child knows. “Oh, you’re just showing off,” even the littlest ones will say scornfully as a way of refusing to concede defeat when they have been shown up. So how do we get people to admire our stuff?

Within the ranks of show-offs, there is special condemnation for those who show off with their possessions. While it is true that pride in having skills or receiving honors is supposed to be masked with humility, kindly disposed people (a category in which Miss Manners oddly places herself) have a certain amount of sympathy for those who occasionally peek out gleefully from under the mask. Achievements are presumably the result of dedication and work, which we do admire openly.

Pride in owning things is not appealing. Although the argument can certainly be made that skill goes into the selection and placement of what one owns, and having paid for it suggests a direct link to working, the sentiment still comes off as crass. What inevitably springs to mind when objects are flaunted is the monetary value they represent, and flaunting money is just not respectable. In spite of our ancestors’ efforts to link wealth with virtue on the grounds that God gives merit raises, anyone who still believes that the rich and poor deserve their respective states is advised not to say so.

Yet charitable people occasionally get excited about having new toys and want to show them off. Miss Manners cannot see a great deal of harm in this, provided they don’t—show off. Perhaps that little distinction is not clear. Perhaps the whole problem is puzzling to a society of crazed consumers. With everyone going around offering critical evaluations of everyone else’s clothes, cars, furniture and groceries, demanding to know where it was all bought and for how much, it may seem unnecessary to worry about how to draw an object of pride to anyone’s attention.

In spite of provocation and temptation, Miss Manners expects polite people to refrain from behaving like shopkeepers and customers in their social lives. She doesn’t care for the attitudes and comments that displaying and examining one another’s wares provokes and tempts them to reveal. To point out every new pair of socks you are wearing, even with the sly approach of asking for an opinion, or to greet everybody who walks through your door with a house tour instead of a drink, is to ask for trouble. There has to be a presumption of particular interest on the part of one’s targeted audience. It’s not nice to go around shouting, “Look what I got!”

Nor do such tactics unfailingly produce admiration. People who can safely be presumed to take a kindly interest are: those who take an interest in every move you make, or lovingly pretend to—in other words, people who love you; shopping pals, for whom the rules about comparing bargains and finds are suspended; collectors or fanciers of the particular item you want to show off; prospective or recent purchasers of the same sort of thing; and those who express enthusiastic interest.

Miss Manners is not saying you cannot stimulate this interest—but only if you recognize that you are honor-bound to listen to advice you solicit, issue house-warming invitations only to people you plan to entertain again, and find occasions to reciprocate the admiration. The last is particularly valuable, as it proves to them that you have good taste.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Our daughters, who enjoy a very casual approach to entertaining—jeans, BBQs, beer from cans and milling around the kitchen, yard or deck—asked my opinion about the display we saw during a gathering at a friend’s house. On the dining room table were china, crystal and silver, along with flowers and candles. No place mats (that’s considered formal), but fancily folded napkins were stuck into the goblets. This was not set for that evening, but as daily decor, as are pillows on the sofa.

The lady of the house received no family training in the social graces, but was led by TV and/or advertisements to believe this “proper” and socially acceptable. My belief is that you display your acquisitions by inviting your guests to your house to use them. Also, since your home is not a restaurant, napkins are not displayed across the dinner plate nor stuffed into goblets. I still think that a bare table is not proper. I can understand that place mats have replaced the old-fashioned tablecloth, but recognize that some place mats are more “formal” than others.

GENTLE READER – Mothers are higher authorities on propriety than television, as Miss Manners trusts your fortunate daughters realize. While she feels sorry for people who don’t learn the common customs of their own society at home, she does expect them to think over what they are seeing elsewhere before copying it.

Surely it takes only common sense to realize that although it is reasonable for advertisers to show off their wares, it is just plain show-offy to display privately owned dinner equipment to people without inviting them to dinner. While she’s at it, this lady might as well show off her cooking by bringing out platters of food without offering her guests any to eat.

Miss Manners could quibble with you about the details of table setting, as two people who know the customs but recognize that they change. She actually doesn’t mind a bare table if the wood is interesting, yet she clings to that “old-fashioned tablecloth” (although not so tenaciously that she pulls the dishes onto the floor), considers place mats to be informal at dinnertime even if they are made from spun gold, and shares your aversion to the silly fad of stuffing napkins in glasses.

The creepy idea of setting up a phantom dinner party goes much deeper, making a mockery of the sacred concept of hospitality. The respectable alternative to formality is informality, such as your daughters practice, not pretentiousness.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – When friends visit your home for the first time, is it impolite not to show them through your home? I was brought up believing it was almost impolite to do so.

GENTLE READER – Far from being a required part of hospitality, house tours, while not actually forbidden, must be accompanied by an excellent excuse from the host and a whole chorus of requests and protests from the guests.

Miss Manners understands perfectly well what you mean by their being “almost impolite.” A house tour, being an invitation to admire a whole range of possessions that may not interest or amuse the tourists, is presumptuous of the host to offer. Yet requesting one seems to demand that people who have extended hospitality in their communal rooms also present their private rooms for inspection.

Suppose you have a host who would love showing off and a guest dying of curiosity? How can they manage to get together?

The host can initiate the idea by saying that he or she has just finished moving in, or redecorating, or mentions some point of historic or other interest in the house, or offers to show an object located elsewhere in the house that has come up in the conversation.

A guest can only bring the subject up by discussing how interesting the house is, and saying brightly “I’d love to see it sometime, if you don’t mind,” the “sometime” allowing the host to smile blandly and agree to that indefinite future, or to jump up and begin at once. If there is such a tour, however, guests must remember to pronounce everything charming. The tediousness of this for either or both parties if there is no genuine interest explains why the tour must be deliberately and mutually negotiated.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I am a working woman who is fortunate enough to own a horse farm just outside the metropolitan area where I work. The farm is most frequently described as a “showplace,” and there, frankly, lies my problem.

My profession is stressful, and I look forward to weekends as a chance to recharge my batteries. I forget about make-up and pantyhose, and spend hours puttering around in my “grubbies” and playing with the Dachshunds, gloriously alone and blissfully relaxed.

Hardly a weekend goes by, however, without the quiet being shattered by the doorbell. There stands a friend or acquaintance—somewhat sheepishly—usually with several complete strangers in tow. The recital nearly always goes, “I know we should have called, but we were driving by and I knew how much my friends would enjoy seeing your beautiful farm and the horses.” I smile weakly and am trapped into what usually amounts to an hour’s tour, followed by the obligatory glass of iced tea or cup of coffee.

Short of putting up locked gates at the farm entry, which I would resist, how can I discourage these people? What would you think of a sign by the courtyard gate that says, “The best friends are those who are expected.” Or, more bluntly, “Please, no unexpected guests.” Seems a little brutal to me, but then, I’m getting desperate. I should add that I am not a recluse and love entertaining, but at times I select!

GENTLE READER – How about issuing megaphones to the dachshunds and then training them to run out and hide in the front bushes? Failing that, you might set up a speaker system with the house, which asks all visitors to identify themselves at the gate, along with a recording that always responds that Madam is not receiving visitors today.

Miss Manners makes these suggestions only to save you from having to appear in your grubbies and enact the following perfectly polite scene:

Open the door only part of the way, and respond to their requests by saying, “Oh, dear, I’m so sorry, this just isn’t a good time for me to show them around. Do drop me a note when you’re planning to be in the neighborhood again, so I can be sure to save some time for you.” Then, with a regretful smile, shut the door.

With a showplace or a hovel, the rules are the same: You do not have to let uninvited people inside your house. The only difference is that when one owns a renowned tourist attraction, it is considered gracious to make a special effort to allow people to see it on one’s own terms. For example, you might volunteer the grounds for a picnic for a worthy organization, now and then. Then you could add to your doorway regrets, “But we’re having a benefit for the county here next week, and I do hope you’ll come.”

The well-appointed house is stocked with things that are much too good for anyone in it.

Miss Manners isn’t making this snobbish judgment. The people who live there are. The same people who bought all that stuff in the first place. The same people who are responsible, through marriage, birth or invitation, for the presence of all those other unworthy people. Everything they own is, in their opinion, too good for their children to go anywhere near, too good for regular family use, and much too much trouble to take out for company.

The concepts of “best” and “everyday” are of long standing, and the distinction was made even in the humblest households with the idea of providing a sense of occasion now and then. The difference between then and now is that such occasions actually did occur. The best things were taken out for guests, but also for the family to use, if not to lend dignity to family dinner every night, then at least on Sundays and holidays, even if no one else was there.

In our times, Miss Manners has observed a downgrading of the worth of the people involved, and a corresponding upgrading of respect for the worth of things. These unpleasant judgments now cover everyone ever likely to cross the threshold and everything in the house that can possibly be put away or placed off limits. Once, it was only the dog who was required to keep his paws off the sofa. Now the guests are being told to keep their shoes off the rug.

It started with the china and the silver, which were so obviously too good for the family that they had to be supplemented by duplicate sets of second-string items—also called “nice,” but less expensive and fragile—made of earthenware and stainless steel. In many households, those, too, are now considered to be too good for any entertaining that is done. Surely paper and plastic are good enough for the kind of people who come for parties, holidays, meetings or weekends. The table linens also went rapidly to paper, obliterating the distinction between the good damask for company and the family’s plain cloth napkins.

Rugs and upholstery soon followed. The vogue for white rugs overcame the illogic of using them to furnish houses in which walking took place. To this day, Miss Manners receives bitter letters from rug owners who have no qualms about exposing their priorities when they complain about guests who balk at taking off their shoes.

Another method of protecting things from people is to place entire rooms off limits. The front parlor was in its glory for visiting clergy and dead relatives—the former to take tea and the latter to be laid out—but was also available for guests. While that concept survives in the modern living room, this room is left empty while guests are entertained in the kitchen, which has been enlarged for the purpose.

Miss Manners can only suppose that the quality of guests has gone down. Even they seem to agree that they are not good enough to use the guest towels.

Even without watching daytime television, Miss Manners has heard enough people talk about their families as to have no illusions about what they think their relatives deserve. She remains puzzled about why, then, it is still customary to stockpile all that good stuff. Surely it would make sense to shop around for better people—or worse stuff.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Either I know more uneducated slobs than the average person, or they just find their way to my home by themselves. I have two guest baths, one up, one down. These baths also can be used with corresponding bedrooms (but rarely are) so there are towel bars. I have very expensive decorator towels on these bars, which I replace with nice towels if the bathroom is to be used by a staying guest.

The problem is that visiting people use these towels after they have used the guest bath. I have guest towels laid out on the sink, but they don’t use them—they walk across the floor, dripping water, and use the decorator towel, which necessitates washing it (do they think I can’t tell?) and shortly ruins the beauty of the towel. I’ve even tried the paper towel route, but nothing helps. I’ve considered making a sign stating “USE THESE,” but that seems crass. I’ve considered taking down my decorative towels, but that leaves a bare towel bar staring you in the face.

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners was all set to sympathize with you when she thought you were plagued with guests who ignored the guest towels for the family towels, out of heaven knows what sense that they were saving you trouble. You lost her with the horrid idea of “decorator towels,” especially “expensive decorator towels.” Miss Manners does not know what decorator towels are, and she doesn’t want to know. No doubt they are all the rage with what you would call educated slobs. She will tell you that anything that hangs in the bathroom and looks like a towel is going to be mistaken for a towel. What belongs on the towel rack of the guest bathroom are guest towels.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I have company coming for two days with a two-year-old, and I have just received a letter saying, “You may want to pack up all the knickknacks from the living room to child-proof the place, or else our son may get into things you don’t want him to.” I have four children of my own, and I always watch them whenever I visit. And I have a large family room where the little boy can play. Instead of packing things away, I am thinking of putting a “child’s security gate” in my living room.

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners has the feeling you may want to pack up all the knickknacks from the living room to child-proof the place, or else their son will most certainly get into things you don’t want him to. His parents have served notice that they are not going to stop him.

As you and Miss Manners both know from having children around, it is possible for parents to tell even toddlers that certain objects or areas—Miss Manners does not know whether we are talking about an ordinary adult household, or one in which a collection of priceless china figurines is displayed in open cases just off the floor—are off limits, and to enforce this through parental vigilance. This is nearly impossible for the hosts to do, both because they do not have the authority, and because it violates the hospitable impulse. As these parents have brought the subject up themselves, however, you could ask whether it wouldn’t be better to tell the child where he might (and might not) play freely.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – At a party we had, with several round tables and chairs for our guests, one gentleman was in a family antique Windsor, leaning back on two legs of the chair. He is quite large. I was across the room, and would have had to maneuver to speak to him quietly or get his attention. I decided to let it go, but ended up with a damaged chair. It didn’t break, but the spindles are now quite weak. I have had this happen before, where someone leans back and rocks on a chair. I am saddened about my chair, but I didn’t want to embarrass my guest, either. Should one politely ask a guest not to lean back on a chair? If my children do it, I always ask them not to.