THE SYSTEM

Life’s basic To-Do List isn’t all that long. On it, typically, are:

That’s only eight tasks, and the same ones that people have been more or less managing since civilization began. So why is everyone suddenly complaining about not having enough time? What has changed besides the shorter workweek, the horseless airplane, the air-conditioned summer, the no-iron fabric and ever more ways of receiving news and entertainment without having to get dressed?

All Miss Manners ever hears is how busy people are. Some of them are just bragging, now that having to work all the time has achieved the status once enjoyed by never having to work. Others are practically weeping from exhaustion. Miss Manners hates to add to their burden by asking them to take the time to reschedule their lives, but the present approach clearly isn’t working. All those categories remain essential, but some of them have been seriously neglected because others have developed too many subcategories.

Earning a living now includes so much faked friendship, what with oxy-moronic workplace partying and business entertaining, that it all but obliterates spending time with friends. Any social time left has, with the assistance of computer games and chat rooms, disappeared into time spent with invisible friends or, as we used to say, alone.

Attending to personal needs has come to require so much devotion to food and exercise that there is hardly time for looking after relatives. What leftover time there is for that has been shifted into agonizing about whether one is doing the right thing by one’s young children, aged parents or mate; this leads to therapy that brings it back, full cycle, to looking after oneself.

Enjoying the arts and keeping up with the world have come to require so many joyless hours of watching television that the more one learns about what needs improving, the less time there is to do anything about it.

Miss Manners would never suggest that anyone eliminate any of the basic tasks. Still, something has to change when everybody has time for files of old jokes circulated by E-mail and nobody has time for dinner at home. She suggests getting rid of those frills that are either no fun or don’t work:

1. Feeling guilty.

Miss Manners never has to feel guilty because she never does anything wrong, but those who are human should substitute doing the best they can and correcting what is wrong. Fretting doesn’t help anyone.

2. Hanging out with people you don’t like but think might be of use to you.

They probably won’t (unless it was in their own interests anyway, in which case it isn’t necessary) and even if they will, you’ll get to feeling bitterly that no one loves you for yourself and, having neglected disinterested family and friends, you’ll be right.

3. Saying yes when you mean no, because it takes longer to get out of something than it does not to get into it. Saying yes for family members without checking, because it takes even more elaborate excuses to explain.

4. Keeping up with the latest in any field other than your work or a beloved hobby, especially when its something in which change is the main point, such as fashionable restaurants or teenage slang. Miss Manners is a hopeless newspaper addict, but even she realizes that there are only so many significant changes in the world.

5. Remembering to stay mad.

6. Improving the world by means of lavish social events for good causes, instead of giving your services or money to those who need it.

7. Goofing off when you should be working, and working when you should be goofing off, so that both activities are ruined by the feeling that you are supposed to be doing something else.

8. Ironing the newspapers.

Ironed newspapers were once considered an essential detail of the properly run establishment, and a self-respecting butler would no more have tolerated the appearance of a newspaper in its natural state than that of a parlormaid in hers. However, since we really must streamline our lives (now that Sunday is no longer a mandated day of rest and there is so much more shopping that has to be done, and now that we have dishwashers and computers and therefore must spend the time our ancestors had at leisure in waiting for repairs to be done on them), Miss Manners will set an example and make that one humble sacrifice as a concession to the pace of life.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Is it acceptable in this day and age to expect ones husband to lend a hand with thank you notes? I know that traditionally, the wife is designated as the social coordinator; however, I come from a large family (and incidentally a very generous family) and I am fortunate enough to be able to acknowledge many thoughtful gifts around the holidays, birthdays and our anniversary. I do not think it would be unreasonable to ask my husband to write thank you notes to his family while I am writing them to mine.

My case is further strengthened by the fact that most of his family lives in Germany and does not speak much English. I do not speak any German, while my husband is fluent. It seems to me that it is a nastier violation of etiquette to expect the entire family to learn English in order to decipher my note than to ask my husband to put pen to paper.

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners has long since abolished the silly custom of dividing household duties by gender. It seems to her that two adults who supposedly love each other should be more interested in reaching a division that is satisfactory to each. Ordinarily, that would mean that each can write some letters or the person who is best at writing letters, or who least dislikes it (nobody except Miss Manners seems actually to enjoy writing letters) is the person to do it, and the other takes on something that person is good at or doesn’t mind. As the job in this case is to write letters in German and you do not speak German, you cannot do this at all, so it is unreasonable of your husband, who can, not to do it.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – In our marriage, my wife “owns” the checkbook. She has a tendency, though, to pay the full amount of every bill the day it arrives and then agonize over being on a tight budget until the next paycheck arrives. How can I politely convince her that she needs to create a budget and take a longer-term view, without sounding condescending?

GENTLE READER – By volunteering to save your wife a great deal of worry by taking over the administration of the checkbook. Or by thanking her for going to the trouble of taking care of these matters without your having to worry and leaving it at that.

Miss Manners has observed that there are people whose idea of financial prudence is to put off paying bills so as to hold on to the money as long as possible, and people whose idea of financial prudence is to pay all bills immediately so as not to risk incurring a finance charge for any delay. A problem arises only when, as in your case, such people are married to each other. Which method prevails is not something on which Miss Manners has a position. She does know that putting one spouse in charge and having the other criticize is not a compromise likely to lead to household peace.

Many devoted parents make sacrifices so that their children can have the enriching experiences provided by after-school athletic and cultural activities. They sacrifice time, energy and money, ferrying the children around, buying them equipment, encouraging them, practicing with them and standing around waiting for them—all so that the children will grow and learn. Some of them also sacrifice their manners and morals. This enables the children to learn irresponsibility and grow into menaces.

Miss Manners has always been the sole defender of stage mothers and Little League fathers, and, as they came along, soccer moms and backstage fathers. She never understood why it is presumed reprehensible to allow children to develop and pursue activities requiring skill, discipline, work, accountability and fairness. She has also noticed that, far from pushing their children, most of these parents are being mightily pulled into these worlds. With or without prompting, their children oddly consider such activities more exciting than what are considered to be the normal young people’s sports (watching television) and art (strolling malls looking at merchandise).

Unfortunately, competitive parenting has now turned too aggressive for Miss Manners to ignore. It is no longer a question of overly rambunctious cheering or sympathetic partisanship; rather, it is one of teaching the kind of behavior that gets champions fined and divas fired—fighting authority, flouting rules, not showing up when expected and, not infrequently, using violence. So if the objective was to give the child professional training, the effect would be counterproductive. Anyway, that is not often a reasonable objective. Few children will be offered opportunities that will allow their parents to turn professional with their coaching. If they are willing to sacrifice that possibility, they can teach the children skills that really will help them become stars of any field in which they have sufficient ability.

Miss Manners admits that the ability to organize one’s time in order to accomplish what one wants, and the responsibility to live up to commitments, ought not to give people an advantage in the working world. Without everybody’s having them, that world doesn’t work very well. As you may have noticed when trying to find reliable workers at any level—and as a result of which these simple attributes are prized.

So parents can help their children most by sacrificing less. Extra activities should be returned to the realm of privilege, requiring the children to wheedle and promise. Let them plan the schedule and do whatever reminding it takes to execute it. Let them learn the rules and take any consequences for breaking them. It is a parent’s job to see that a child meets all the requirements of school and family obligations, but extras should be earned.

Miss Manners realizes that it takes practice for a parent to develop the callousness to say “I’m not surprised you got kicked out—you’re always late for rehearsal” and “It doesn’t matter what you or I thought—if the umpire says you’re out, you’re out.” This sacrifice is worth making. If you can’t turn your children into artists or athletes, you can at least turn them into champion planners.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I have found my social plans changed more and more often by close friends who are also well-meaning parents, to suit the schedule or temperament of their children. They are in effect putting the young ones’ needs above all the adults concerned, even when we, the childless couple, are the hosts or organizers.

These are not formal occasions or adult-only gatherings where a sitter would be hired, but casual get-togethers such as picnics, cookouts, etc. or short meals in family-style restaurants. The children are no longer infants but 4- or 5-year-olds, usually without siblings.

I have suggested a time or place to meet, only to find out that the food or dinner hour doesn’t suit Junior’s schedule. Then I find myself bending over backwards just to come up with something that agrees with everyone or suggesting diversions for the little one.

I truly enjoy both the parents and the children’s company, but the logistics are exhausting! On the other hand, I often find myself excluded from such things as luncheons where the moms do gather with the children!

I am very aware that children have different needs than adults, shorter attention spans, etc., which is why I limit my invitations to casual occasions. However, when I was young, my parents took us lots of places where we were expected to behave (the old “seen and not heard” theory) even if we were bored, unhappy, restless, etc. My personal belief is that today’s children will never learn to cope with these unpleasantries if they never have to learn to handle them while young.

Of course, my more immediate problem is how to handle my own social life: Should I make new friends that are also childless? Forget my parenting friends for the next 10 years? Stop trying to have a social life unless I hire a playmate for their child or an on-site sitter? Or is this an etiquette concern at all? And another observation: When did it become acceptable social conversation to discuss in great detail Junior’s potty training efforts?

GENTLE READER – People who talk potty should be seen and not heard; Miss Manners doesn’t care how old they are.

Still, this is only a stage that your friends are going through. Surely you think them worth hanging on to, and your desire to include their children is admirable. The children of friends eventually make excellent friends themselves, if you stick with them.

Meanwhile, although your friends should not be making plans they have to change, you, as host, should be suggesting plans that you think will be agreeable to all your guests, regardless of age. Please don’t invoke that seen-and-not-heard business—parents go ballistic when they hear that, just as if they thought it could work or ever really did. If, instead, you ask their help in fashioning plans that would please everyone, you would be entitled to insist that they not be frivolously changed.

P.S. Don’t fret about being excluded from the mother-and-child luncheons; you don’t want to know what they’re discussing.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Picture this: The radio or TV “speaks” in the background. Daughter engages Dad in conversation. In the middle of a meaningful sentence, Dad raises his finger in the air, signaling her to stop instantly, while he listens to sports scores. Daughter is told to hold the thought until after the report. Daughter, who is 11, challenges this behavior, claiming it is a demeaning interruption and poor manners. Dad says she’s oversensitive and unreasonable, because her thought can be said any time and the scores can only be heard once a day.

I am certain that the finger method of stopping conversation is rude, but I wonder if even the sweetest, most humble “Excuse me, could you hold that thought for just a minute?” is not also demeaning. Is stopping a person in mid-sentence for anything but emergencies rude? My husband says you’d answer differently if it were war news, rather than sports scores. I think we should learn together the self-discipline of truly listening to one thing or person at a time, and cease dividing our attention.

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners is with you on the issue of divided attention, and trusts that you have not allowed this daughter to do homework while listening to music and have never, never, never permitted any canned entertainment during dinner. But your husband may be surprised to hear that she has a point to make in his favor, as well. It’s not because she considers war news (which often qualifies for emergency status) more important than sports scores. If the scores are given only once a day, both father and daughter should be aware when that is. It is no time to begin a conversation. If your daughter opened with “Is this a good time to talk to you?” she would be right to expect his full attention if he says yes. That means the television should be turned off.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I am a hard-working patriotic, productive citizen who works two jobs to raise my family. When I am home, I treasure the time with my wife and three young kids, and I try to guard our privacy carefully. What I don’t understand is how strangers could bang on my door, ring my telephone or send me junk mail with no regards to our valuable time.

Is it rude not to answer the door if I know it is some kind of religious group, charity organization or people who take surveys? Is it rude to hang up the phone once I found out the person is trying to sell me something? Is it rude (and a waste of paper) to throw away junk mail without opening it? If your answers are yes, is there a better way to deal with these situations?

GENTLE READER – If productive citizens were required to be open to all offers they receive, they would not be productive very long. Or respectable, for that matter.

Politeness does not require you to open your door or your telephone line to, or your mail from, strangers. It does not permit you to hang up on them or slam the door in their faces, but it permits you to ring off or close up (Miss Manners trusts that you understand the difference) immediately after saying “I’m sorry but I’m not interested.” The reason these people importune you is that there are people whom they do manage to interest. So your declining to waste their time is as considerate of them as it is of your family life.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – My neighbors feel free to stop by our house for a chat whenever the mood strikes them. Much as I like these people, I work long days and so look forward to private evenings at home with my family How can I get the message across that unannounced visits are unwelcome? It’s especially hard to get them to leave once they’re in the door, though I act tired and distracted and eager to get on with, say, making dinner or giving my daughter a bath. If I go upstairs, they stay and talk with my husband!

GENTLE READER – How do these undesirable visitors get in the door? Do they pick the lock with hairpins? Do they claim to be delivering a lottery prize? Or do you open the door and say “Oh, hi; well, come on in,” and step back to let them pass? Miss Manners suspects the last. Although she knows you do this out of a sense of politeness, bless your heart, she has to teach you to stop. She will even teach you to stop politely.

Dropping in used to be a neighborly thing to do, but that was before the invention of the telephone. Even when it was polite to call on people without advance notice, it was also polite to be unable to receive them. The two go together.

It helped to have someone to announce that you weren’t at home, which is difficult to do on your own behalf, although peepholes and answering machines make excellent guards. If caught, you must do the next best thing, which is to say that you are not available. The polite way is to pour out expressions of anguished regret while barring the door: “Oh, dear, I wish I’d known you were coming, because I would love to have had a chance to visit with you. Give me a call another day and we’ll find a convenient time for all of us.”

DEAR MISS MANNERS – A friend who knows I am an early riser phoned me to chat at 6:40 A.M. I must admit to being less than receptive to social conversation at this hour. I always thought social calls were properly made between 8 A.M. and 10 P.M. Care to comment?

GENTLE READER – Not at this hour. Of course, you don’t know which hour this is. Miss Manners is afraid that although your friend knows that you are an early riser—and therefore considerately called you early—the fact that you are not an early converser is something you don’t seem to have mentioned.

The standard polite hours for social telephoning are 9 A.M. to 9 P.M., but not during working hours, which are roughly between 9 and 5:30, or between 12 and 2 because it might be lunchtime, and not from 5:30 to 9 because it might be time for preparing or eating dinner.

Perhaps you begin to see why it is a good idea to let one’s friends know when you like to chat—and for the friends to inquire, when they do call, whether it, in fact, is a good time on that particular day.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – My husband works over 70 hours a week, so I cherish the time before he leaves for work for conversation, and the weekends taking turns sharing him with the three children.

Neighbors pop in on me uninvited and, when I politely ask them to come back later, make me feel terrible with comments like “Oh, I’m sorry we bothered you” or “I didn’t know we would be intruding.” Another thing—when I say politely to come back later, they certainly do! What I really want to say is “Leave me alone until I invite you to barbecue or play cards. I don’t have time for friends with three kids and a husband.”

GENTLE READER – No, you don’t want to say that. Trust Miss Manners. You don’t even want to think that. This isn’t only a question of its being rude to insult people who offer you friendship, even those who go about it with no manners and less charm. What worries her is your illusion that having a family means that you don’t need friends and you don’t need to be on mildly friendly terms with your neighbors.

Miss Manners agrees that it is rude to drop in without warning—it has been since the invention of the telephone. And centuries before that, human society became possible only because of a tacit pact to suppress skepticism about other people’s pleas of being busy. Nevertheless, a family that walls itself off is going to run into trouble. As your children grow, both they and you will increasingly need the society of friends, and even now, in the midst of such a busy time, you all need the protection of having neighbors who, if not full-fledged friends, are at least not enemies.

The better way to ward off intrusions would be to offer your own terms. If you and your family made just one effort to entertain the neighbors, your plea that your family schedule unfortunately prevents you from enjoying spontaneous visits would be more sympathetically accepted.

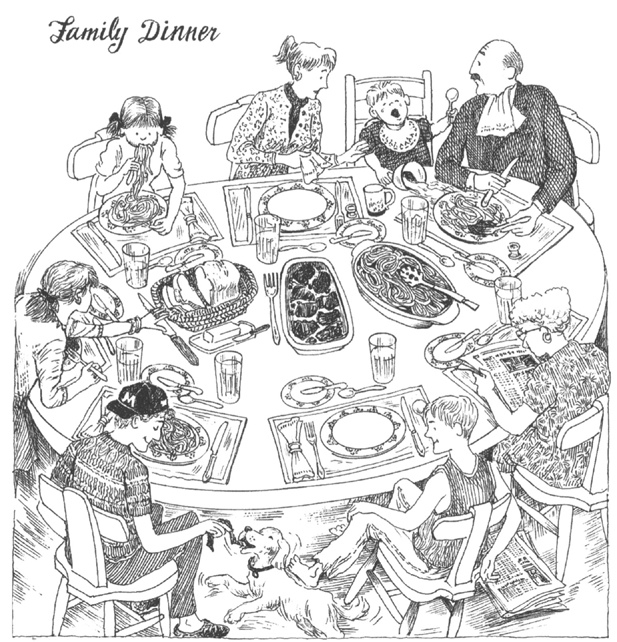

Most households, whatever their size, have a room or an alcove dominated by a large table surrounded by chairs. Why? Some of the people who live there think it is storage space. Others think of it as a communal desk or the home for the 500-piece puzzle (or so it claims on the box, although actually there are only 497 pieces). But you can also eat there. Miss Manners knows that sounds silly.

There are so many rooms in which to eat: the kitchen, of course; every room that has a television set; every room that has a computer; every bedroom, even if they don’t have both; the bathrooms if they have Jacuzzis or at least tubs with ledges for trays; and the front hall on the way out the door. Why mess up another room?

Miss Manners will tell you why: because a household where the members do not sit down at dinner together nearly every night is a convenience store, not a home. A home is a place where the residents, whatever their relationship to one another, perform the nightly ritual of breaking their bread and news together.

Now she probably also has to tell you how. Restaurant manners used to be taught as a variation on family table manners, but that was back when going out to dinner was a rarer occurrence than sitting down to dinner at home. It has become necessary to point out that the strange ritual of eating at home does not include deciding whether one wants to do so or not, ordering what one likes regardless of what other people are eating, complaining about what one doesn’t like or starting to eat at the first sight of food and quitting the table when full or bored, although others are still eating. On the plus side, tipping isn’t required.

It does require fixing a time when everyone can be home, even if that means the break between someone’s day shift and someone else’s night shift, and learning to say “Sorry, have to go; I’m expected home for dinner.” Then one has to dress for dinner—an expression that is less likely to mean evening clothes, as it once did, as to mean clothes. Exercise outfits are not clothes. There is work involved, because actual plates, flatware and napkins are used, and yes, Miss Manners knows that means they must be put in a dishwasher or soapy sink instead of in the trash. Just don’t use the poverty argument on her, because reusing things is cheaper.

It even requires table manners.

DAILY DINNER: The family dinner table is where civilization is taught—not only table manners but the art of conversation and the principle of consideration for others—and this one has a long way to go. The table has been properly set for an informal meal, with main course, bread-and-butter (to go on the small plates), dessert (to be eaten with the spoon above each plate) and, miraculously, real napkins, identified by napkin rings so they don’t get one another’s food stains while awaiting laundry day, and no television set anywhere in sight. However, Mother is in a stupor of exhaustion from earning the grocery money and mopping up after the baby, and it would be nice if the grandparents, instead of eating piggishly and rudely reading, were helping her explain the impropriety of showing up in underwear, bare feet, slippers or baseball cap, and of grabbing a knife by its blade and inhaling the pasta.

Family dinner allows a certain leeway—it is lax enough to permit reasonable bone gnawing and sauce mopping but not commercial cartons on tables. Everyone must learn to sit (as opposed to supporting the body by resting the left arm on the table and wrapping it around the plate) and to operate that mysterious instrument that terrorizes everyone—the fork.

Because there is no background music, no recitals of today’s specials, no looking up to watch the game, no getting up to answer the telephone, family dinner requires being able to talk. This skill should not be confused with what one hears on talk shows. You do get to complain and to brag, because it’s family, but you have to fill in with conversation. Rather than being a series of pronouncements, confessions and fights, this involves building on what other people are saying, rather than waiting (or not waiting) for them to finish.

If all this sounds like less fun than the food court, it is because the rewards may be cumulative. By teaching eating and social skills, the family dinner dissolves the terror people claim to feel when they are required to seem civilized, if not charming, for social or business reasons. Therefore it precludes the necessity of having to confide in strangers in cyberspace because no one else will stop to listen.

Presuming that you are both aware and observant of the rule of etiquette that forbids throwing food, which Miss Manners realizes may be taking a wildly optimistic leap, what can you do to shock people nowadays at the dinner table?

You certainly can’t say anything to shock them. Whatever confession you can make, no matter how far removed from normal human behavior, they are going to yawn. They already heard your nasty habit discussed on television, and are in the grips of the deadening certainty that you are about to tell them all about your boring support group.

Miss Manners doesn’t know that she has to supply shock material. There are enough people open-mouthed at the dinner table as it is, in violation of the rule against behavior that rivals food throwing on the Disgust Scale. (Actually, you can sometimes throw food: You can play toss outdoors with an apple or a pumpkin, depending on your weight class. Not so much fun? Well, you can spit watermelon seeds in a watermelon-seed-spitting contest, or in preparation for the Watermelon-Seed-Spitting Olympics, provided you do it outdoors and face away from the crowd.)

The fact is that it is fun to shock people at the dinner table, and one can do it effectively with proper table manners that are startling to those who are not familiar with them. We are not going to stoop to retrieve manners that have been stricken from the books. Yes, there was a time when picking the teeth at the table was acceptable, more centuries ago than Miss Manners cares to remember, but it was also a time when drinking cups were shared, and one washed out one’s mouth by spitting into bowls provided for the purpose. But many perfectly good rules that are still on the books are unknown to most people, whose parents considered themselves lucky if they could get across the basics, and didn’t even attempt the oddities and the exceptions. These fall into three general categories:

1. Setting the Table Funny.

Four was the minimum number for which a table used to be set, and to set it that way for two or three people is guaranteed to keep those people looking over their shoulders all evening.

Old European silver is engraved on the back, and intended to be placed on the table facing the tablecloth as if it were in disgrace. This, too, makes guests very, very nervous as they imagine you set the table upside down, and are worried about what you might do next.

Everyone knows what an entree is, only everybody is wrong. Properly speaking, the entree is not the main course but a light course, such as an egg dish or risotto or a light meat, that comes between the fish course and the meat course. You get a delayed reaction if you serve a true entrée, because the shock comes after they filled up and are then faced with the main event.

2. Picking Up Things That People Think You’re Not Supposed to Pick Up.

Everyone knows you are supposed to eat your vegetables with your fork, but asparagus can be properly eaten with the fingers. (Stalks and all. A lady of Miss Manners’ acquaintance sent her a report of dear Jonathan Swift’s admonishing a guest for asking for seconds in asparagus tips: “Sir, first finish what you have on your plate.” “What, Sir,” was the reply, “eat my stalks!” “Ay, Sir! King William always ate his stalks!” Yes, Miss Manners knows it isn’t polite to notice what your guests are eating, let alone to boss them around. But she doesn’t feel up to taking on Jonathan Swift today.)

Everyone knows you are supposed to remove the inedible by putting it quietly back on the fork in which it arrived. But although fish goes in the mouth on a fork (unless you are a diver), the bones are taken out with the hands.

Everyone knows that soup must be eaten with the spoon, in a direction away from one’s own dry cleaning. But bouillon cups with two handles may be picked up and the soup may be drunk. (So may be the guests, but that is not on Miss Manners’ list of what is proper.)

3. Attacking Food with Strange Implements.

Everyone knows that you use a knife to spread butter, except that a potato is properly buttered with the fork.

Everyone knows that you can’t eat fish with a meat knife or warts will grow on the back of your hand, but it is proper to eat fish with two forks.

Any idiot knows that you eat ice cream with your tongue, or with a spoon, but in the absence of an ice cream fork or an ice cream shovel, ice cream is properly eaten with both a fork and a spoon.

Doesn’t that all sound like fun? Then why are you sitting there blowing bubbles in your milk?

DEAR MISS MANNERS – With all the relaxed meals we have nowadays, takeout meals and order-ins, my family’s table manners are deteriorating. My thirteen-year-old son thinks nothing of dipping and dunking the most unimaginable sets of food groups with each other, not to mention my husband forgetting that there are actually utensils to get the food from serving dish to plate, as well as the constant reminder to the entire family that elbows really don’t belong on the table. How can I bring some civility back to dining in the home?

GENTLE READER – By dining, instead of grazing. Where you get your food is of no concern to Miss Manners, but if you allow fast-food manners in the household, she is surprised that your child has enough manners to be described as deteriorating.

The crisis in eating manners is widespread, but it astonishes Miss Manners. It is not as though these were esoteric routines that people rarely have a chance to practice. A culture’s eating customs are supposed to be routinely taught by parents to children and practiced daily under their supervision.

You must, of course, enlist your husband’s help. Unfortunately, habits are taught by example as well as nagging. Fortunately, once learned, they are no less “relaxing” than unauthorized eating methods.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Several of us ladies at work all have the same complaint about our grown up children (mine are in college, the others are divorced, single adults of a second marriage or single, living on their own): They dine and dash. They never bring anything, offer to help clean up or invite us to dinner. When confronted, all of them said they are guests, and guests don’t help. We would agree with that statement if they were occasional guests, but we’re talking about several meals a week or every weekend. In actuality, we are subsidizing their meals, because they are struggling financially. None of us mind cooking family meals—in fact, we enjoy it. But we do mind being treated with such lack of consideration.

We, the parents, agree that children are never guests. This is a lame excuse for laziness. Children will always be part of the family and should contribute by bringing a dessert, helping clean up (which is more than taking their dish to the sink) or inviting us to dinner. These ladies are about to close their soup kitchens because of lack of respect. We raised our children with manners, but somewhere along the line, they lost them. We don’t even get the token of a tip, like most good waitresses—just the mess to clean and a big insult from the ones we love.

GENTLE READER – Guests wait to be invited, write thank you letters afterwards and try to entertain their hosts as many times as they are entertained by them. If they are intimates of the household, they offer help when it seems to be needed. So Miss Manners believes that your grown-up children would be better off being relatives, even if they had a choice, but you shouldn’t be giving them that bogus choice. You may have reared the children properly while they were at home, but your job is not finished. It is time to teach them the manners of grown-up children dining at their parents’.

“Tidy” is a dear little word, and Miss Manners is sorry to see it pass out of use. Swept under the rug, as it were.

It is true that we have other ways of referring to people who enjoy keeping things neat, who pick up after themselves without being threatened and who maintain their homes nicely for themselves and other residents, instead of making desperate swipes at order only when guests are expected. Still, the modern terms for “tidy” don’t have the same charm. Miss Manners doesn’t care for either “anal-compulsive” or “control freak.”

Even less does she care for the modern habit of redefining good habits as signs of bad character. It is clever to declare one’s weakness a virtue and demand to be not just forgiven for ones lapses but admired. However, this ploy is at the expense of the dutiful, who are made to feel sheepish and apologetic about doing the right thing. Characterizing themselves as warm human beings (although Miss Manners does not quite understand how this automatically follows from an inability to put anything where it belongs), the unorganized routinely accuse the organized with whom they have supposedly warm relationships of petty larceny, petty tyranny and small-scale sabotage:

“Did you take my glasses?”

“I must have given you the tickets, because I don’t have them.”

“No, it’s not my fault; you’re the one who forgot to remind me.”

“I would have put them in the dishwasher, but it was full, and I would have put the clean stuff away, but I don’t know where you keep things and I knew you’d be upset if I didn’t put everything away exactly where you think it should be.”

“Why didn’t you tell me it was my mother’s birthday?”

“Of course I had to open another bottle—how was I to know that there were already two open in the refrigerator?”

“I didn’t stand you up. I just didn’t look at my calendar.”

“Okay, what did you do with my keys this time?”

This is not warm human-type behavior. The justification, which is that no harm is done because anyone who keeps up with check-off lists more than three days after New Year’s does not possess human feelings, is worse. How often topsyturvy morality works when the suitors of young ladies argue that any resistance would mark them as cold and inhuman, Miss Manners cannot say. She does know that the notion that messiness is a warm and endearing trait, while orderliness is freakish, enjoys amazing success. Even people who truly love order commonly refer disparagingly to their own good habits.

None of this would be a problem if tidy and sloppy people didn’t live together. Indeed, no self-respecting roommate referral system would pair people who see no point in making a bed—because they’ll only sleep in it again—with those whose idea of a good point is hospital corners. It takes romance to make such volatile living arrangements. Love seems to be no respecter of personal habits, and people who can’t tell the difference between a house and a hamper inexplicably manage to attract people who alphabetize everything they have, short of the children.

Incidentally, Miss Manners does not consider children the chief problem, and thank you, she does not care to view the state in which yours leave their rooms. Children are works in progress, and a surprising number turn out to want to live pleasantly the minute they leave home. The problem is between people of equal claim to running the house and unequal interest in maintaining it. Adults who live together cannot politely go around saying “Don’t think you’re going anywhere until you clean up this pigsty.”

Miss Manners does not charge that the fact of being disorganized is rude—only that it often leads to rudeness in the way of inconveniencing and blaming others. She even acknowledges that the hopeless, if only they would stop bragging about their deficiencies, might also be human and therefore entitled to a reasonably peaceful life.

This is best accomplished by allowing them their own out-of-sight territory to keep as they wish. Miss Manners is a great believer in household zoning. In an ideal household, such a person would be assigned a separate bathroom, study and dressing room; in an average one, the free territory might only be inside a closet and a drawer.

Instead of receiving this gratefully, the mess-maker may notice that it implies that common territory must therefore be maintained at the higher standard, which is exactly what Miss Manners means. She brooks no nonsense about untidiness and tidiness being different systems of equal merit, nor about those who prefer the former having the same say as those who prefer the latter. A sloppy adult is not on the same august level as a tidy one.

She does not go so far as to assert that they have the same maintenance responsibilities. People who don’t understand about order are never going to be able to manage it, so there is nothing to be gained by expecting it of them. What one can reasonably require of them is that they close what they open, put things back where they got them, replenish supplies that they use up, and not appropriate the pens and umbrellas of the tidy person on the grounds that they can’t find their own.

Organizationally gifted or not, everybody has to take just enough responsibility for managing time, duty and space to keep from making havoc of responsible people’s lives, inside the household and out. This means that everybody maintains a calendar of his or her own appointments, and participates in a master household calendar, although the disorganized must understand that they have no authority to accept invitations on behalf of others or perhaps even for themselves.

A central command post (and while electronic ones are admittedly seductive, nothing has replaced the refrigerator door, the one place everybody stops) not only enables the organized to spot conflicts and to issue reminders but it enables the disorganized to find them in case of emergency—having first agreed upon the definition of an emergency, and whether it includes “I can’t find my skis!”

As long as they learn such basic household skills as leaving the newspaper intact and replacing the toilet paper instead of leaving unpleasant surprises, more complex duties can be assigned according to individual talents. Some people should never be asked to keep track of when Thanksgiving will occur, much less to connect this with the necessity of buying a turkey; they can compensate by performing tasks that they can master. Those who aren’t sharp enough to be in charge of taking the car in for inspection while it is still legally possible to drive it can still be trained to take out the trash.

Even Miss Manners doesn’t expect the disorganized to be able to figure out where their own scissors are or make a connection between running out of shampoo and buying more. That would be too much to expect. She does, however, expect them to resist the temptation to allow these shortcomings to lead them into a life of rudeness and thievery. In return, she expects the tidy person to keep a pleasant tone when revealing for the thousandth time where the spoons and dictionaries are kept. Noblesse oblige.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – My boyfriend and I have different opinions when it comes to what is “done” and “not done,” most recently on whether leaving ones underwear on the floor is rude or perfectly acceptable. I think it would be embarrassing for someone to walk in my room and see that intimate article of clothing strewn across the room. My boyfriend doesn’t see what the big deal is.

I want to add that he leaves practically everything else lying around, too- cigarettes, food, half-empty glasses, and “half-clean clothes.” Do I just have, as he claims, a silly social hang-up?

GENTLE READER – Apparently you have several: You are under the odd impression that a well kept house is better than a slovenly one. You think guests might not enjoy being forced to look at their hosts’ underwear. You think you should have some say in how you live.

Miss Manners can understand that love is a powerful force and induces people to live with those whose personal habits are not as nice as their own. She fails to understand how anyone could bear to live with a person who strews around that meaningless but vaguely insulting word “hang-ups” to describe civilized living and/or your particular preferences.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I leave dishes in my sink for days at a time. I know—I should be banished from civilized society, especially since I am about to add that I left dishes in my sink AND I invited a friend over. While I was upstairs, my friend decided to do me a favor and wash the dishes. It’s not that I don’t appreciate the help. At the time, I thanked him and felt relieved from an onerous task. It wasn’t until later that I made the discovery that his idea of clean is the same as mine—only 25% less. He put dirty dishes back in the cupboard! Last night, he did it again. I thought it would be wrong to criticize an act performed as a gift, so I just told him I preferred he didn’t do it at all, without explaining why. Now his feelings are hurt. He thinks I’m being inexplicably rigid and seems to be wondering what kind of psycho wife I might turn out to be.

GENTLE READER – Now just a minute here; please slow down and let Miss Manners figure out what you are actually saying. This is not just a friend, is it? By mentioning your concern with his opinion of you as a wife, you do plant that little thought that you might be considering him as a husband. In any case, he is eager to help around the house. Specifically, he has been eager to perform a task you hate and avoid to the point of preferring—Miss Manners is only echoing your own judgment—a degree of slovenliness. Yet this gentleman does not wash dishes to your satisfaction. Miss Manners has a hard time figuring out how his standards could be 25% lower than yours, since you don’t wash them at all, but so be it.

Now—your solution to all this is that he should be discouraged from washing your dishes. Are you mad? If he were a casual acquaintance, certainly. One could say that his helpfulness crossed the border of intrusiveness, since he decided to clean up from a meal he did not share. But do you really think you must persuade a possible husband not to do any housework because he doesn’t do it to the satisfaction of a possible wife who doesn’t want to do it either?

Why don’t you exert yourself, instead, in making the task easier for him? If you must leave your dishes in the sink, leave them soaking in soapy water. Not only will this suggest to him that you are at least trying, but the dishes will be easier for him to clean satisfactorily

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I live with my fiancé and we are planning to marry next summer. We have already co-habitated for the past three years. I love him dearly and cannot imagine life without him. My problem is that he is a slob. Nothing I have done can remedy the problem. I have tried threats, thrown tantrums, joked about it, even thrown quantities of dirty dishes and clothes away, much to his surprise. My question to you is … is there anything I haven’t tried? Leaving him over such a problem is not an option I would ever entertain … but it’s driving me crazy!!

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners is pretty sure you haven’t tried picking up after him. Any self-respecting lady would consider this far too degrading, not to mention sexist.

One of the nice things about marriage (Miss Manners needn’t list others as you have already discovered them) is that you can make any sort of deal that suits you both. And the pleasantest work-sharing deal is not necessarily the one that would strike outsiders as fair, but one in which each of you does tasks you don’t mind, while not having to do ones you dislike.

Surely there must be jobs that you hate to do that your fiancé would be willing to take on if you do the neatening up. In return for taking care of the dirty dishes and clothes, you ought to bargain to saddle him with quite a large load of work.

If the farmer and the cowboy should be friends, what about the housewife and the businesswoman? Miss Manners would put it to music if that would help, but she’s too busy. Actually, she isn’t. Miss Manners’ idea of being busy is having to use her own dimpled knees to get the porch swing going because there is no one around to push it for her.

Meanwhile, all the other ladies are locked into a fierce competition over who is busiest, and she doesn’t want to feel left out. Why this should be such an issue between housewives and businesswomen that they spend their time scorning one another, Miss Manners cannot imagine. Don’t they have anything better to do?

Housewives are asked to give their occupations when out socially and are then roundly snubbed. Other ladies who talk to them at all go in for such conversation openers as “What on earth do you do with yourself all day?” and “Aren’t you bored?” As a result, many housewives have been driven to the unseemly defense of declaring how much money they would get if they sold their personal services to their families instead of giving them away

Miss Manners faints dead away when she hears this. That argument is horrid enough when it comes from divorcing husbands who, having once agreed to split the work of earning the family living and that of sustaining family life, turn around and claim that the latter obviously wasn’t worth anything much because they didn’t pay for it. Ladies don’t need to encourage them.

Although housewives now assume that the attack on them is unprecedented, Miss Manners is old enough to remember how ladies who were doing paid work were charged to their faces with being selfish and worse. Salaries—such as they were—were considered to be a factor only in the lives of those who had improvident husbands or none at all (the latter condition being viewed as a matter of choice only in the sense that no one must have chosen them). Therefore, the only attraction of working had to be the opportunities and alibis it provided for promiscuity.

The workplace is no longer thought to be that exciting, but there has been a recurrence of slurs nevertheless. Housewives may routinely get the worst of it now that the society has adopted the counter-historical idea that people who work for wages are of higher status than those who preside over their own domains, but they also cast blame.

Whenever a tragedy occurs involving a child who was not under the immediate supervision of his or her mother because of that lady’s job, it is open season on the mother in question and, by extension, every other such mother. Never mind who actually perpetrated the particular accident or crime. Never mind the shocking number of children being hurt by their own parents. Never mind that a mother who was with her child every hour of the day or night might inspire matricide.

Therefore, many ladies with jobs have been driven to the unseemly defense of pleading how deprived their families would be if they did not sell their services in the marketplace. Miss Manners doesn’t like that version any better than the other one. She would like to see some sympathy among ladies, who all share the problem of balancing their contributions to their families and in the outside world, however different their solutions. If sympathy is not possible, Miss Manners would settle for some decorum.

Polite people show other adults the respect of acknowledging—or pretending—that they must know best how to run their own lives. They do not ask insulting questions, make accusations, draw unpleasant morals or offer unsolicited advice. If they haven’t yet learned that people who talk about their jobs are among the world’s great bores, they at least follow the social custom of addressing people as individuals, not job descriptions. They certainly do not discuss their own or anyone else’s personal life in terms of its market value. People who sell their personal attentions do not belong in polite society.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – A young woman said that I, as a wife “who doesn’t work,” am “the Cadillac of the 90s.” Since I have three young children, surely she did not mean that I don’t work. Perhaps she was saying I don’t get paid and my husband is rich enough to keep me.

Because I do not have an income, we, as a family, manage without a lot of things that many Americans think are necessities. Far from being a luxurious commodity, I am incredibly versatile and indispensable to my family. Should I attempt to enlighten this person about how insensitive her comment was, or merely accept that she is a social clod?

GENTLE READER – Before you take insult, you might want to check what kind of car this lady has. No, maybe you’d better not. You would also have to know how well it’s running. You’re already devoting too much thought to a thoughtless remark.

Miss Manners doesn’t care to defend people who make impertinent assumptions about other peoples lives and resources, but she guesses this was a wistful remark that had more to do with the speaker’s feelings about herself than with her estimation of you. It was certainly cloddish, but probably not meant to be demeaning.

Nobody knows better than Miss Manners that cloddishness is a social menace, but apparently no one else knows that the cure for it is not the cloddishness of going around “enlightening” people about how unpleasant one finds their pleasantries. If you were directly queried about your finances or criticized, you might have registered your displeasure with a freezingly polite “How kind of you to take an interest in my personal life.” Here, a cold “Thank you” would have been enough to suggest that you are satisfied enough with your life to assume that any comment upon it would consist of admiration.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – What is the ideal relationship between secretary and wife of the executive? The secretary sees him more hours during the day, knows his business associates, and takes part in what seems to be the most important part of his life—therefore, sometimes creating resentment on the wife’s part. The wife’s role is usually to do the things no one else wants to do, i.e., care of the young and the elderly (all of which America seems to warehouse) and spends many years inundated with diapers and bottles.

The husband spends all his years bettering himself as an executive and officer of a company and acquiring power, while the wife receives very little recognition and little time for mental stimulation spending her life being a wife, mother and homemaker.

A whole week for secretaries? There is only one day for mothers, and no day for wives. There should be some other way to reward secretaries for a job well done other than a social lunch with several drinks before. I have been both. As a secretary, I kept a very businesslike relationship and my president or vice president boss never took me to lunch; however, I planned many for him. I was not a wallflower, having spent some time as a model and I have a degree from a prominent university. I knew their wives and had great respect for them. I don’t find myself in a similar situation, and feel that secretaries are going too far.

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners tries not to get personal with the etiquette questions but feels obliged to point out that your problem is not with secretaries—your husband’s or anyone else’s. Your problem is with your own present occupation. Nowadays, ladies who can afford to stay at home with their children generally do so because they find this satisfying. Such a person would not, however, refer to domestic life in the loaded terms you use. As you are a trained secretary, Miss Manners suggests you might want to return to being one, rather than blaming your husband’s for your dissatisfaction with your share of his attention.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I am writing on behalf of myself and another female colleague d’un certain age, in regard to certain assumptions our husbands d’un certain era make in regard to their right to intrude in the professional lives of spouses. Most particularly we wonder if calling one’s wife at the office to tell her what is desired for the evening meal or asking that she leave a meeting to be informed about a plumbing malfunction in the home is acceptable. In addition, we would like to know if it is proper for a spouse to complain to an administrator at his wife’s place of business about the fact that his wife, on occasion, must toil past the time that her contract states that she is expected to be on duty.

GENTLE READER – At un certain age, you may have forgotten un certain routine you once used to teach the children manners. This was called How Would You Feel If? Miss Manners suggests you learn to play it again.

Typically, this went “Don’t take away the toy your brother is playing with. How would you feel if he took away a toy you were playing with? Don’t shove your sister. How would you feel if she shoved you?” and so on. It wasn’t sparkling dialogue, but a certain primitive understanding eventually developed.

Now is the time to trot it out again: “Please don’t interrupt me at work. How would you feel if I interrupted you at work? How would you feel if I complained to your boss about your hours?”

Miss Manners recognizes that it is barely possible a husband may be slightly quicker at this sort of thing than a small child, and may arrive earlier at the traditional crisis point. This occurs when, lulled into that way of talking, you say something like “Don’t pull the cat’s tail. How would you feel if she pulled your tail?” and the child proudly announces, “I don’t care—I don’t have a tail!” So perhaps the husband, with a smirk only too similar to his child’s long ago, replies “I don’t care if you call my boss—I am the boss!” or “Go ahead and interrupt me at work—I’m retired!”

The reply to the tail-less child, if you recall, was to pull a bit of hair and say “Well, that’s what it feels like.” With the husband, too, you may have to find something equivalent. If he is the boss, you complain to his deputy (in front of him) that he must be sent home on time, and discouraged from believing that he is indispensable. If he is retired, you have him paged on the golf course and ask him to do an errand on the way home. Miss Manners has a feeling this may not actually be necessary. Husbands tend to be more experienced than children, and have probably learned to accept the mere mention of retaliation in place of the deed.

The many people who now do office or other professional work from their homes are decidedly testy about it, Miss Manners has noticed. Having no such wonderful buffer as a secretary, who can filter the outside world to them in useful and bearable doses, they have taken to snarling “CANT YOU SEE I’M WORKING?”

Neighbors drop by uninvited. Computers call to make unsolicited solicitations. Strangers appear at the door to spread religion or pitch politics. Friends telephone to chat. Children come and go at will. Housemates deplete the office supplies and play games with the office equipment. People who seem to have nothing to do look to them for companionship. People who are busy ask them to do their errands and household tasks.

The polite ones, bless their hearts, feel an obligation to let others consume their time. So they let them natter on with the mistaken idea that it would be impolite to cut them off. The rude ones are no better off. By blasting would-be consumers of their time, they leave the way open for counterattacks, which take up more time, and they get themselves into emotional states that interfere with work more than interruptions. Spoken or unspoken, however, the bitter response is always “CANT YOU SEE I’M WORKING?”

Miss Manners doesn’t condone interrupting people at work, but she doesn’t care for all that shouting, either. There is an underlying problem for both sides here that she would like to point out: “NO, THEY CANT SEE THAT YOU’RE WORKING.” (Please excuse Miss Manners. What she meant to say over the din, in her wee, ladylike voice, was “No, they can’t see that you’re working.”)

Any lady who has worked around the clock to run a household, rear children and serve her community could have told them that work done at home never really registers as being work. Furthermore, boundaries of time and space that once protected the sanctity of the home have now disappeared. The place has been so thoroughly invaded by those who bring in non-domestic work—from the burdened soul who has to bring work home to get everything done, to the sly one who hopes to soften up associates by turning them into guests—that it is impossible to tell who, among those at home, is working and who is not. They’re home, aren’t they?

The home office may also do duty as a sitting or dining room. The home worker may take time off during the day and put in extra hours in the evening. People who work at home have also been known to do their thinking in ways not traditionally associated with office work: while straightening the closets, watching the news or standing in front of an open refrigerator. These people are especially indignant when others assume that what they are doing is goofing off or puttering and that they may therefore be interrupted.

Miss Manners is not disputing that one may be doing urgent work while apparently relaxing, just as the computer has enabled the office worker to relax with games and interoffice chatter while apparently working. She is only suggesting that the worker need not assume a lack of respect for his or her work when others are confused about where and when it is being done. Someone who appears at the door in a bathrobe at noon, or who tries to beg off from chatting after dinnertime, doesn’t look convincing when making the excuse of being in the middle of work, truthful as it may be.

All one has to do is to tell them. Nicely. Patterns of work should be announced to anyone likely to trespass:

“When my study door is shut, please don’t interrupt unless it’s an emergency.”

“Call me in the evening—I can’t talk during the day.”

“I’m sorry I can’t talk now; I’m in the middle of a work project.”

“This is not a good time to visit—I work during the day.”

Anybody who works and lives in the same place should take control of all means of ingress, deciding whom to let in and when. The answering machine and the door peephole are the poor person’s receptionist. Self-secretarial service consists of putting the telephone on an answering machine and ignoring the doorbell or telling those who ring it that you are not interested (if you don’t know them) or not free until later (if you do).

It is not rude to say pleasantly (but with an air of preoccupation to illustrate the point) “I’m terribly sorry but I’m busy, so I must ask you to excuse me; goodbye” without providing an opportunity for the intruder to argue the point. No one need feel apologetic about not being available to everyone all the time—not even someone who is indulging in the office-sanctioned task of woolgathering.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – When I try working from home the phone seems to ring every 15 minutes so I have taken to turning the ringer down and returning all calls at the end of the day. So many people hang up without leaving a message, or hang up and call right back to try to get me to pick up, or leave a loud message saying “HOW COME YOU NEVER PICK UP THE PHONE?” Do callers have any right to be so hostile, and to try to fool me into picking up? How do you ask a couple of chatters, obviously cyberflirting big time, to chill out?

GENTLE READER – That wasn’t your boss calling, was it? Or the person waiting for the report you promised to turn in three days ago?

Presuming that your work does not involve taking telephone calls—don’t take them. Don’t take bullying on the subject, either. People who turn hostile when you don’t jump to do their bidding are exactly the sort you should be screening out—probably out of your life, Miss Manners would guess, as well as your workday.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I feel like a prisoner in my own home. I am a teacher, and I often have work to do after school hours, such as grading papers, preparing assignments and tests, recording grades, writing progress reports, contacting parents on the telephone, and similar tasks. I often have to stay home to carry out this work while my family goes to a movie or some other family activity.

Today is one such day. Someone rang the doorbell and I decided not to answer. Apparently the caller waited a while or went around the block, because the bell rang again about ten minutes later. Just as I picked up the thread of my work, it rang again. Can’t people realize that if nobody answers, it has to be due to one of two reasons: No one is home (and the caller is therefore wasting his time), or someone is home but must have a good reason for not answering, which should be respected.

Twice in the last few months, I did answer the door and although I explained politely that I had these school deadlines to meet and that was why I had stayed home, the callers stayed on while insisting they would only take a few minutes of my time. One was actually still here four hours later! My family returned from their outing tired and hungry, and I had not even had the chance to put some food together, let alone complete my work. So now I don’t open the door, but I feel angry, guilty, imposed upon; in one word, unhappy. A friend of mine tells me it is bad manners not to answer the door or the telephone if I am at home. I say the unannounced caller should accept the fact that the time is not right and then leave or hang up after a few rings and no more than two tries.

GENTLE READER – Modern guilt is a wonderful thing. Here you were, home, minding your own business as it were, sacrificing your recreation to do your admirable work, hoping to get done in time to feed your little family, and some unlicensed judge of manners has made you feel that you did something wrong. Why? Why would you even consider the idea that you do not have a right to dispose of your own time in your own house?

Miss Manners suggests you learn to ignore or unplug the telephone or put it on an answering machine, and that you ignore or tape over the doorbell. Should you weaken and answer the door, learn to say politely that you are working—while standing firmly in the doorway and blocking the way in. She also suggests you stop taking illicit etiquette advice from interested parties.

It’s not that Miss Manners doesn’t know how you eat when you are standing there with the refrigerator door open, and what your idea of grooming, let alone proper dress, is when you’re not planning to go anywhere. She hasn’t a word to say about it because she considers it none of her business.

Etiquette is social behavior, and the sure way to get safely away from its demands is to stay home alone, shut the door and pull down the shades. There is really no such thing as being rude to oneself, and even Miss Manners doesn’t do etiquette for hermits. It would be rude to intrude.

If anyone else is present, it is a different matter. Miss Manners does not care for the popular idea that being related and/or in love means you don’t have to worry about the other person’s sensibilities, a concept that has done so much to promote the broken home. Or, as those who advocate the etiquette-free home environment put it with an amazing zest for self-condemnation, “I just like to be myself at home.” Oh, so that’s who that awful person is.

But if it doesn’t affect anyone else, and your wallowing self doesn’t bother your critical self, why should Miss Manners care? She gets the day off too, knowing you are safely isolated, where you are not going to inspire etiquette complaints.

Suppose, however, it does bother your own self? As Miss Manners is aware, more people are working at home now by the flickering light of friendly computers. They still have, of course, etiquette obligations to those on the receiving end of their telephones, telephone modems, E-mail and bulletin boards.

Interrupters—the definition of people who call at the one moment of the day when the home worker didn’t happen to be wondering whom to call for a little chat to while away the time before inspiration struck—may be dealt with briefly and firmly, but not rudely.

What no one else can see, hear or read doesn’t count. That is the great advantage that manners has over morals. If you’re not caught, there is no reason to register fault even on your conscience. Nevertheless, Miss Manners also knows that the thrill of an occasional release from social expectations can turn ugly when it becomes a way of life. So while she promises not to peek to see how anyone is doing, she offers, with uncharacteristic timidity, a few suggestions for optional etiquette as a courtesy to oneself.

As everyone knows, the proper dress for working at home is as close to night-wear as possible—soft, fuzzy and requiring little in the way of a support system. It is still dress, though, in the sense that it requires changing. With that goes a modicum of what may laughingly be termed grooming. This may be only a way of thinking about what goes undone: An unshaven gentleman should think of himself as “considering growing a beard,” and a lady who leaves off whatever customary makeup she wears classifies this as “letting the skin rest.” (Miss Manners doesn’t even want to think about people who postpone brushing their teeth.)

By the same reasoning, beds should be made upon arising unless they are decently covered with the thought that one will be working like crazy for a short time and then taking a refreshing nap. Meals should be—meals. Miss Manners did promise she wouldn’t look, out of concern for her own equanimity as much as for anyone else’s privacy. She also promises that the person who sets a nice table will be happier than the person who doesn’t use a saucer under every cup and bowl. All right—who doesn’t actually sit down to eat. All right—who doesn’t actually use eating tools.

Miss Manners would consider it a sensible precaution never to go more than two days without getting physically out of the house. This is not the health tips department, so it’s not that. The purpose is to remind oneself that one is actually visible, in a world where other people exist. Frightening as this may be, it serves as a valuable warning not to let etiquette skills rust away. She hopes these few rules do not seem unnecessarily strict, and she has been told that no one who works at home follows them to the letter. She wouldn’t dream of prying to find out.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Long-time friends who both work out of their home invited us to spend the following day with them, suggesting a time. When we called ahead in the morning, however, we were advised, along with several reasons why, that one of the couple would be working while the rest of us ate and visited. Our attempt at canceling was sharply countered with a question as to whether this person’s not working was to be “a prerequisite” for our attendance. This scenario, with the exception of our bowing out and the resultant unpleasant confrontation, has been oft repeated.

What are we to think? Either the person is truly busy and doesn’t need the additional task of entertaining guests—or could this be a way of “politely” avoiding us?

GENTLE READER – One of the peculiarities of our time is the blur between work time and leisure. As Miss Manners understands it, the office is the place where showers and birthday parties are held, while the home is where mere socializing is a disturbance to serious people. Of course, it should be a prerequisite for accepting an invitation to be assured that your hosts were free to entertain you. No considerate person would intrude on someone’s working hours. No considerate person would invite guests with no intention of entertaining them.

Having just returned from a short business trip, a lady of Miss Manners’ acquaintance embraced her husband at the airport and opened the sort of conversation that cozy couples have when they are reunited.

“Did you mail those packages I left?” she asked. “I hope you remembered to send them insured. I don’t have any cash left, but I figured you’d have gone to the bank. Did you finally fix the porch light? I keep telling you it’s dangerous not to have that working. I left you a message about picking up the dry cleaning—it’s important because there’s a dress I really need for tomorrow. Did you call my parents? I didn’t have time, and I don’t want them to worry about me. I skipped dinner on the plane, so I hope you have something we can have as soon as we get home because I’m starving. You did pick up the groceries on the list I left you, didn’t you? Oh, don’t tell me we have to stop for gas—I’m exhausted. Why didn’t you get it on the way here?”

After a while, the lady noticed that she had not been receiving replies to her questions, so she stopped to give her husband a chance. Besides, although she was still keyed up from the trip, she was beginning to run out of breath.

“My dear,” said her husband as he navigated through airport traffic, “the sight of a 747 soaring through the air is a wonderful thing. It’s amazing to see it up there looking so powerful and free. But do you have any idea of the size of the ground crew it takes to keep it up there?”

Fortunately, that was all the gentleman needed to say. Even normally considerate people need an occasional reminder that they are not the only ones tearing around trying to get a lot of things done. Life on the road seems so much more disjointed than life at home that it is especially apt to give the traveler the delusion those left behind are at leisure. Furthermore, several days of doing nothing but business encourages the businesslike attitude of issuing instructions and expecting them to be followed.

This is not, however, a polite approach to take to family life. Miss Manners does not subscribe to the fantasy that business travel is a life of hotel and restaurant luxury, for which penance is expected in the way of compensatory duty at home. But since a family member who is subject to business trips heavily depends on extra help from the ground crew at home, it is wise, as well as polite and kind, to express appreciation for what is done and sympathetic tolerance for what was not done.

That this etiquette was only sketchily observed in the era when the traveler was nearly always the gentleman of the family and the support service was supplied by the lady does not make it less true. It does mean that spouses will have to develop dexterity in switching from making extra claims while away to doing double work when at home. It also means that—as with any other relative or friend who pitches in to compensate for travel absences—massive doses of appreciation will have to fly around in all directions.

Is Miss Manners the only person who is repulsed by that poster of a child—usually leering out of a resort gift shop window—captioned “What did you bring me?”

“Nothing, kid,” any sensible person should be prompted to reply, “and what’s more, I’m suddenly awfully sorry I came to see you.” One can’t actually say that—Miss Manners cares for rudeness towards children even less than she does for rudeness from children. Nevertheless, any person so attacked should make sure to teach the lesson that rudeness, amounting in this case to emotional blackmail, doesn’t work. Grandparents—the poster is sometimes targeted to them, in the charming hope of convincing the aged that they can expect no unpurchased affection—may simply have to become forgetful on the matter of bringing presents at all. “Why, I hoped you’d be pleased simply to see me,” they should say in astonishment; “I’m certainly happy just to see you.”

Parents, especially those who have kindly sought to sweeten their absences for business trips by returning laden with gifts, will find that they, too, encounter this unpleasant welcome if they have not taught etiquette rules to the contrary. Relying on the fact that the child will, indeed, be happy to have the parent back, and having had this feeling bolstered by the child’s protests against the parent’s leaving for the trip, one can easily neglect to teach the rule about going for the open arms before going for the luggage.

One homecoming in which it appears that the primary interest is anticipation of material gain should be cruel enough to convince a parent that something is wrong. Those who go in for psychological complications may prattle of hidden resentments associated with fears of desertion. Miss Manners believes it to be a simple matter of etiquette.

One can love a person to distraction, with no reservations whatsoever, and still focus first on the glittering object in that person’s hand. Ladies who receive romantic proposals often have to remind themselves to look deeply into the beloved’s eyes before examining the diamond in the ring.

If gratitude toward the giver, much less the clear expression of it, were a natural instinct, nobody would ever have to be prodded to write a thank you letter. Also, not all presents are successful. Expressing love for the impulse of present-giving nevertheless is a refinement of civilization that must be taught.

Therefore, the child-rearing system of leaving children to express all their emotions uninhibited by the requirements of etiquette is a mistake. Parents who have depended on their children always to harbor and to express acceptable emotions are always going to encounter trouble. One must teach the artificial habit of associating the pleasure in a present with the generosity of the giver.

This is done by careful instruction in the proper welcome, along with an explanation of how wonderful it feels for a homecoming parent or a visitor to see smiles and happy faces. It also helps if the practice of bringing presents is somewhat irregular, not always expected as the child’s due. It is the child who does not demand to know what was brought who should be given the pleasure of a genuine surprise.