ENTERTAINING: THE SOCIAL EVENT

Entertaining at home is the perfect hobby for a society where everybody is in show business. Everyone already knows the format, and having people sit on your very own sofa talking directly to you is ever so much more fun than eavesdropping on the conversation of talk show guests, who remain oblivious to all the clever comments you throw their way. As a live host, you get to be both director and star, although you are required to observe union demands (from the etiquette union) to attend to the well-being of others. You get to pick the style and arrange the lighting in the setting you designed. You get to throw people together in combinations of your own devising and watch what happens. To top it off, everybody is obliged to keep telling you how perfectly marvelous you are.

Miss Manners isn’t fooled by all those claims that we are much too casual (read charmingly folksy and modest) for that kind of thing. Then who are all those people who devote years to planning and restaging their elaborate weddings, freaking out if anyone questions their orders? How come civic activities, from politics to philanthropy, only attract people when they are packaged as fancy parties? Why should carefully arranged seating plans be considered silly at dinner parties but meaningful at fashion openings?

Of all social scripts, the best is for small, seated dinner parties, because nobody gets left out and everybody gets to sit down. If family dinner is the root of civilization (or whatever other metaphors Miss Manners may use in her tireless effort to promote the outrageous concept of nightly gatherings with other people who happen to live in the same house), the sit-down dinner party is its flower.

Formal or informal—or the in-between style that has become the standard for modern dinner parties—the basic procedure is the same. A half dozen to a dozen carefully chosen people gather at a specific hour (or up to eight minutes after), freshly turned out and primed for the pleasures of talk and table. They are given a drink, a nibble and a chance to become acquainted or catch up before being led to their places at a candlelit table and fed.

For the host or hostess to serve guests from platters at the table is both the modern informal and the ancient formal way of offering food. The modern formal way is to have footmen carry around platters of food from which guests help themselves while pretending not to recognize the footmen as their own party help or the hosts’ children.

If this is too elaborate, there are other charming scripts for entertaining at home. Meals by daylight are lighter, even formal luncheons, where bouillon and salad and sherbet are considered filling, if not actually lavish; or brunches where heating the breads from the bakery and making pretty patterns of the goodies from the delicatessen is considered the mark of a fine cook.

To serve even less food, you invite people who already have dinner plans—offering a cold supper after the theater, or late evening dessert; or you invite people between meals—for morning coffee or afternoon tea. Although the former is the least formal of invitations, and often the coziest, the latter is now thought immensely grand.

However, if you serve cocktails and hors d’oeuvres in the late afternoon, once the sophisticated way to entertain, your guests will descend into fuzzy shock as, one by one, they realize that they have to go elsewhere to forage for dinner. The way to entertain a lot of people at once is still to make them stand up—indoors, if you don’t mind risking your rug, and outdoors during those eleven days a year when it isn’t too hot or too cold—but whether you bill it as a buffet dinner or a cocktail buffet, it amounts to the same thing. Whatever its form, there is so little such live entertainment being done that you will soon have a full house, with others clamoring to be admitted.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – My husband and I entertain quite often, our favorite being small dinners with friends. We do all the work equally, and they always go off well.

My only problem is that my husband is a sports nut. Our large dining room connects to the living room, and if a big game is on, he insists on leaving the television on so he can glimpse it during the meal. It can only be seen by half the table, and the sound is off, but I still think it is wrong. He says he just glances at it, and that just about everyone watches television while eating, these days.

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners refuses to rescind the absolute rule against television during dinner, much less dinner parties, other than for events specifically planned around a particular television broadcast. For goodness’ sake, can’t you invite people over when there is no game on, or record it for viewing later?

Suppose you are really unable, ever, to reciprocate hospitality? Must you then vow social celibacy? Mindful of Miss Manners’ admonition that hospitality has to be returned by hospitality—that it cannot be paid for, event by event; that someone who brings a present or a dish to a host has not thus canceled his or her social indebtedness—a Gentle Reader pleads extenuating circumstances.

“Consider, please, those associates who will never reciprocate in kind because they cannot,” she writes. “They are bright and fun, they will bring gourmet dishes, money, love, and brilliant party decor 35 miles. But their house is not my house because of a sour spouse, a sour house, a kid just out of jail, and other embarrassments they cannot cover up because they work 50 hours a week and commute another 20.

“Also, they are convinced that nobody would show up if asked. People are sometimes sensitive enough to detect this situation. So some arrange a fair contribution by everyone concerned, so as to have a celebration. Someone who may not have gourmet dishes, money, love or decor may have a decent place not more than 50 miles from everyone. Where does fair sharing end, and taking advantage begin? That line, that line, it must be somewhere … snuffle, snuffle, sniff, sniff. Please be plain.”

Yes, yes, yes, but please stop crying. Miss Manners cannot bear it. Here, have a lavender-scented handkerchief.

Miss Manners never meant to be so harsh as to outlaw the cooperative party, or to advise those who entertain to keep strict accounts of return invitations in order to drop delinquents. However, there have been so many abuses of hospitality on the part of both hosts and guests that she really must set strict limits on exceptions to the principle of social reciprocity. Not only has it become common first to invite people and then to inform them that they must cook or pay, but a shocking number of such events are in honor of the hosts—to celebrate a birthday, an anniversary, or even a wedding. That is not a cooperative party. It is a mockery of hospitality, in which someone pretending to entertain is actually tricking others into doing the work and meeting the expenses of entertaining.

A legitimate cooperative party is one in which several people decide to entertain themselves, sharing the responsibilities. Consent is sought ahead of time, because everyone concerned is a host as well as a guest. Such an event can be done in someone’s honor, if that person is excluded from being a host, but it cannot be done in honor of oneself.

“Shall we all get together and put on a party for me?” is not a proper invitation. Nor is a proper social attitude “You can always be the host, and I’ll always be the guest,” no matter how generous a guest one may be.

Miss Manners has a great deal of sympathy for those who find it impossible to entertain and is happy to carry them through such a period. She does notice that some of them have too much sympathy for themselves, and not enough for those who entertain them.

Simply being busy, or not having fancy equipment, is not an excuse for not bearing one’s share of the social burden. Neither is being young or poor or having small children. All these circumstances legitimately influence the way one entertains. People should entertain in a style they can manage, not in imitation of other people’s standards. A family-style hamburger supper is a perfectly respectable return on a formal dinner.

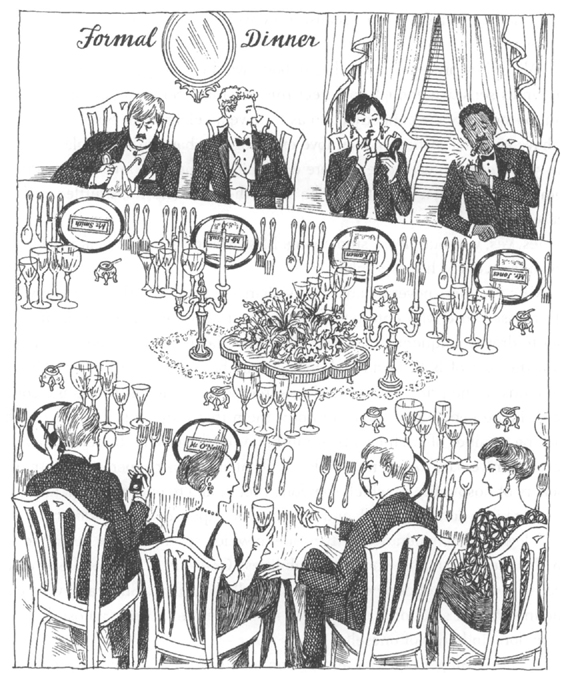

THE GRAND DINNER: The table is properly set, but, as so often happens, the guests are out of control. The great dinner party problem is not the cliché about which fork to use. (Obviously the spoon is intended for the soup, after which one has only to go from outside the plate to in to find the fish knife and fork, meat knife and fork, and salad knife and fork in the order of those courses, while the dessert silver will arrive with the dessert.) Rather it is the rudeness of using a dinner party to take telephone calls, smoke, apply makeup, collect silver, hit on one’s dinner partner and commit other rudenesses. And this is just before they’ve started serious drinking (the glasses, right to left, are for sherry with the soup, white wine with the fish, red wine with the meat, water when desperately needed and champagne in back to go with the dessert), although the lady down front still has an iron grip, in an improperly gloved fist, on her pre-dinner drink.

Those who cannot invite people to their homes should entertain out. If the expense of a restaurant meal is impossible, they could thoughtfully arrange a much cheaper excursion, such as a nature walk or museum trek with a stop for coffee or ice cream. The point is to initiate and plan entertainment for other people. Even those who have the resources to give frequent elaborate parties are grateful if someone else thinks of doing the inviting and arranging, for a change. It makes them feel appreciated in a way that no present, no matter how thoughtful, can do.

For nearly a thousand years, the same ghastly fear has been gripping humanity.

Death? Disease? Starvation? Annihilation?

No, forks. Well, sure, those other things too. But when there is no imminent danger, the fear of choice is forks.

When Miss Manners first heard this, she was stunned. Those nice forks that only want to nourish people and keep their clothes clean? How can anyone be reduced to cowering by a common household item? Nevertheless, the confession of Fear of Forks—more specifically, the deadly fear of using the wrong fork—is made so boldly and so often that she cannot imagine that everybody who claims to be suffering from it is making this up just to tweak her.

Miss Manners understands that few people who announce that they are flummoxed by this complicated and sinister instrument are admitting ineptitude. The rest are bragging. The declaration of not knowing which fork to use is intended to prove how sensitive one is, on the grounds that only a heartless snob would know how to eat.

Some form of this fear has been rampant at least since the 11th century, when it was uncharitably suggested that the folly of using a fork when the fingers would do would be sure to provoke God’s wrath. Nowadays, it isn’t the mere fact of using a fork that puts the fear of God into people so much as the idea of being given a multiple-choice test at the table. As they always put it: “I see five forks all lined up, and I’m terrified because I don’t know which is the one I’m supposed to use.”

The interesting thing about this problem is that it doesn’t exist in real life. It never happened and it couldn’t happen, not even to people who believe it has happened to them. Miss Manners always inquires politely where exactly it was that those five forks were laid out, and she always gets the sort of puzzled-and-panicked look that was supposedly directed at the flatware. The fact is that nowhere, not even at the White House, would a place be properly set with more than three forks. Formal dinners are rarely more than four courses nowadays (and one is usually soup, which has no truck with forks), but even if more forks were needed, it would be incorrect to place them on the table. Any fourth or fifth fork would have to be brought in with the course for which it was needed.

The rule for choosing among the original three is ridiculously simple: Always take the one farthest from the plate. If you make a mistake, it’s the fault of the person who set the table wrong. If you still manage to choose the wrong one, you can rest assured that this is the least detectable social crime you can commit. Polite people are, by definition, barred from monitoring how others are eating, much less sniffing at them. Furthermore, anyone who ate the fish with the meat fork ought to have the fish fork left with which to eat the meat. (If not, there’s a more serious crime being committed than simply misusing a fork.)

Yet Miss Manners does understand the historical reason why Fear of Forks persists as a fantasy nightmare. A variety of highly specialized forks existed only for a few decades, until about World War I, when life got streamlined—and it became profitable to melt them down for the silver. Nobody except Miss Manners still has bacon forks or strawberry forks or ramekin forks or terrapin forks, but during the Industrial Revolution, the fork business had gone wild, probably because name-brand sneakers hadn’t been invented yet, and people who became suddenly rich needed ways to spend their money and show off to their poorer friends.

This made no impression on the fading upper classes, whose inherited silver didn’t include these newly invented specialized forks. (The actual fortunes of this “kind of people” did make an impression on them, which they demonstrated by marrying their sons to the new heiresses.) They continued to use plain forks and spoke witheringly of “the kind of people who buy their silver.” It made an indelible impression, however, on the not-so-rich, who were dazzled by the outlay of dedicated forks, confused about which was which, and intimidated into believing that this branded them as inferior. Generations later, they are still frightened. Miss Manners hereby absolves them—not of the necessity of eating properly but of the notion that they need fear being tested on defunct details.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – My husband is a wonderful barbecue chef, and one of his requested specialties at our frequent pool parties is a marinated, crispy-skinned chicken. I was appalled to see one of our guests sitting casually in front of a platter of smoking-hot chicken, stripping the crispy skin from every piece and eating it, licking her fingers as she did so. She then returned each denuded piece to the platter, presumably for the other guests to enjoy.

Miss Manners, this is not an ignorant woman. She is a graduate of a fine Eastern college for women and has an MBA degree. She is a well-regarded financial planner for a prestigious brokerage. I am amazed that she indulged such a porcine habit so publicly. More to the point, is there a polite way to rescue future barbecued chicken for our guests who prefer their food unskinned—and unfingered?

I thought of snatching the greasy hand and giving it a quick minatory slap, along with the admonition, “No! That’s nasty!” This seems appropriate to the immaturity of the offense, but I know Miss Manners wouldn’t allow it, and I would like to stay on speaking terms with the offender. I also thought of packing up the stripped meat in a plastic container and presenting it to the lady as she left, saying, “We weren’t able to use this, but we thought perhaps you might.” Again, I think this measure fails the Miss Manners test, though more subtly.

Our dog, Mitzi, thought the chicken was delicious and had no fault to find with its skinned condition. Possibly I need to cultivate her attitude of nonchalance, but I just can’t.

GENTLE READER – As you so admirably demonstrate, a polite hostess does not embarrass her guests, even porcine ones. In this case, you protected the offending guest by controlling yourself, which could not have been easy, and you protected your other guests by finding them something else to eat, which couldn’t have been easy, either. Miss Manners congratulates you on both your manners and your larder.

The way to protect future guests is to spare them being invited with someone who is so thoroughly out of civilized control. The way to protect that person is to invite her only with those who will find her manners agreeable. The candidate who springs to Miss Manners’ mind is Mitzi.

The following anecdote about a grand etiquetteer of the past was told to Miss Manners by a prominent national politician:

It seems that many administrations ago, this great lady was dining at the White House, where she was seated next to a well-known Washington figure of the time (who told the story to the gentleman who told it to Miss Manners). The original storyteller reported that he had inquired of the lady whether she was indeed the great authority on behavior, and upon her confirming this, retorted, “Well, you’re eating my salad.”

Tee-hee.

Miss Manners is not amused. It’s not only because she has heard this story before and with a variety of people cast in the roles of Pretentious Lady and Man-of-Good-Sense-and-of-the-People. Nor does she fail to roll on the floor with uncontrollable merriment because she took offense at the affront to an august colleague in the noble field of etiquette (cheeky as that is).

The story flops because it is just not plausible. It didn’t happen, not to that lady nor to any of the others about whom it is told.

How can Miss Manners be sure of that when she was not present? Because at formal dinners, salad is served as a separate course, after the main course. It is unthinkable that dinner partners would have gone most of the way through the meal without introducing themselves. Their salad plates would be placed right in front of them, not to each person’s left, as when salad is informally served to the side of the main course.

Furthermore, until the current administration, food was properly offered to the guests from platters, not slapped down in ready-filled plates, so the lady would have had to put her own salad on her plate. To eat her dinner partner’s salad would have involved ignoring what she had just put in front of herself and leaning over to eat from the plate directly in front of him.

Etiquette is peculiarly blessed in having this sneaky control on those who delight in demeaning etiquette without being versed in it. By the same test, it is obvious that people who gleefully report that some highly proper person looked at them aghast for making a trivial error—almost always “choosing the wrong fork”—are faking. By definition, no proper person would register that someone else had made a mistake.

Other noble callings are not so fortunate as to have all this built-in protection. For example, you could probably say just about anything about a politician and be believed.

Miss Manners understands that there is no point in meeting people of reputation unless one can come away with an anecdote that illustrates one of the following premises:

She also sympathizes with the fact that as most such people prefer not to make spectacles of themselves, their behavior is reasonably ordinary and there is not much dramatic material available in routine encounters. She can hardly expect anyone to report having met someone interesting and yet reply to the inevitable question “What is he like?” by saying “Pleasant enough, I suppose, I don’t really know.” So she supposes that all she can ask in the name of good manners is that gossipers try, if at all possible, to be kind. And if they can’t be kind, they should at least be truthful.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – At dinners in the homes of acquaintances (very special evenings: formal dinners, semi formal attire expected, where we go prepared with gifts for the couple in anticipation of a great evening) there were separate tables to accommodate the guests. Some were seated in the dining room with the finest china, stemware, silver and fabulous decorations and others at a table in either the kitchen with clearly the everyday ware or, in my humble opinion, worse yet, in hallways or some other room of the house.

While I understand that the intent of the hosts may be to include many of their friends at one time for such an evening, I think the practice is demeaning to those relegated to other areas of the house than the dining room with the hosts. Whether I am seated in the main room with the hosts or relegated elsewhere, jokes are always made about being at the “B” table. I am left feeling uncomfortable no matter what. My husband and I are in disagreement as to the correctness of this practice. Am I being overly sensitive and formal on this issue and should I just be gracious in accepting further invitations, or is this practice lacking in manners?

GENTLE READER – Would you both be satisfied if Miss Manners condones the practice but condemns the way your hosts managed it? Probably not. Miss Manners feels like being even-handed, anyway, because that is what it takes to manage A and B tables without insulting the guests.

The rule is that if they can tell which is A and which is B, you’ve been rude. Clearly, the dining room outranks the kitchen, the hosts’ table outranks a hostless one, and the good stuff outranks the everyday table things. But what would you say if the kitchen table were set with the best things and the hostess presided over it? Suppose you were put in the dining room and your husband in the kitchen, and other couples were similarly split between the two rooms? And the hosts went around whispering such things as “I’ve put you near me so we can have a good talk” or “We consider you such an intimate of the house that I’m going to ask you to sit in the middle next to someone who is dying to meet you”?

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I know the guests of honor sit at the right hand of the host and hostess, but at a little dinner party I am planning, two couples are equally important to me and they are also in the same age bracket. How do I seat them so that the one will not feel less important than the other?

GENTLE READER – If there is no obvious difference of age, rank (such as one person’s being a member of the clergy or Miss Manners) or intimacy (people you know better yield the place of honor to newer guests) you must befuddle these couples so they can’t figure out how you ranked them. This is done by seating the wife of one couple at the host’s right, and the husband of the other couple at the hostess’s right. Even the pickiest guests can only argue afterwards about whether you like her better than him, which—whatever it does to the marriage—at least leaves you in the clear.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Over the years, I have hosted many dinner parties, and have occasionally been confronted by a couple who have taken umbrage that I have not seated them next to each other. Couples have even changed their place cards without telling me.

I recently had an experience that tested the limits of my social conscience. It was a birthday party for 60 people. It took me two and a half hours to complete the seating arrangement. When I was confronted by three couples—and heard about two others—who complained about not being seated together, I adamantly (but politely, of course) refused to change the seating.

GENTLE READER – You are, of course, correct that married couples should never be seated together at dinner parties. This is for their own good. Separating them gives each a chance to tell shared stories without fear of contradiction.

Perhaps because this is a time when many marriages are of little more duration than dinner parties, there are those who try to seize every moment. Your guests are doing so rudely, by attempting to take your seating arrangement into their own hands. You can’t separate them by force on the spot, but you should take note of their wanting to spend the evening talking to each other and not trouble them by suggesting they again leave the conjugal harmony of their very own dinner table for yours.

Miss Manners also has some misgivings about your spending two and a half hours doing a seating chart. It is easy to become more devoted to one’s own masterpiece than to the social good it is intended to create. Take that as just a little cautionary note. Miss Manners would be relieved to hear that you are putting an equal effort into introducing the guests to one another once they arrive, and helping them kick off mutually satisfying conversations.

At the Miss Manners’ family dinner table, when guests are not present, napkin rings are used in the traditional way. That is to say, each member of the family has a different napkin ring (in this case, the designs are different, but it is also customary to have similar rings with identifying names or initials), replaces it on the napkin after a meal and thus is able to receive the same napkin for use at the next meal.

“Do you mean to say,” she has been asked incredulously, “that you don’t have fresh napkins at every meal?”

Well, yes, that is what Miss Manners means, if not what she had necessarily meant to reveal. Just as ordinary households have the sheets and towels changed once a week (not twice a day, as fastidious tycoons with full-time laundresses are said to demand, since tycoons require afternoon naps on fresh sheets to soften the stress of all that money), ordinary households have the napkins changed every few days, barring accidents or finger food orgies.

Or so Miss Manners had thought until she encountered this reaction. Are other people doing a load of napkins every day, one for each meal that each member of the family takes at home? Since Miss Manners agrees that in an ideal world, there would be no recycling of used napkins, ought she to be spending her time attending to the home question rather than the world’s etiquette problems?

Not really. The world of etiquette is not unfamiliar with compromise and trade-offs, and Miss Manners can live with recycled napkins in order to have time for doing anything else, and in order not to create a water shortage. It was only later that Miss Manners discovered the real meaning of those questions. It seems that she has survived into a world where people believe that napkin rings are useless but decorative items to be put out on the company table.

Of course there are always fresh napkins out for company, which is why napkin rings were strictly an informal, family device that would be considered ludicrous at a dinner party. But it seems that there are also now fresh napkins out for each family meal—not because household laundry has increased but because the definition of napkin has come to mean something made out of paper. Cloth napkins are thought to be too much trouble in a busy modern household.

Miss Manners urges a revival of daily cloth napkins, along with the labor-saving napkin rings. Contrary to anti-etiquette propaganda, various prematurely abandoned tableware devices were not invented in order to put sensible people to unnecessary expense and trouble. On the contrary. For example, finger bowls have survived only where they are least needed—at formal dinners, where there is little likelihood of finger food being served. The effete versions on doilies, floating rose petals, to be put to one side untouched by the diner, disguise the fact that finger bowls properly serve the purpose of a moist towelette in a package. Salad knives have pretty much passed out of use (but not at Miss Manners’ table), but it continues to be impossible to cut a wedge of lettuce or tomato with the side of a fork.

In regard to napkin ring usage, Miss Manners has been asked whether it isn’t disgusting to reuse a napkin one has used before. Not if you also use another quaint old tradition that has also fallen into disuse. Table manners.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I’m having an on-going disagreement with my club members concerning the placement of large cloth napkins when giving a formal luncheon or dinner. I was taught that napkins are to be folded and placed on the left of the silverware or stuffed in the water goblet, but never forced into the smaller wine goblet where they flop over most ungracefully—but which my friends say is proper.

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners is about to make a lot of enemies—perhaps even you among them—by taking your side. Well, sort of taking your side.

The fact is that Miss Manners loathes napkins stuffed into drinking glasses. They remind her of handkerchiefs stuffed into jacket breast pockets, which, in turn, makes her worry what will happen if the gentleman sneezes and he doesn’t want to use his show handkerchief, and there goes her appetite. However, she is well aware that stating these prejudices infuriates otherwise polite people, who never think to rebel when she only tells them how to run the world or their lives.

Miss Manners apologizes that she cannot interest herself in whether the silly thing is hanging out of the water glass or the wine glass. Napkins belong on the service plate or to the left of the forks.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – My mother taught me (although she was mistaken about some things and may have been mistaken in this case) that the choice of bowls and spoons for soup is determined by the type of soup one is serving: Round spoons and bowls or two-handled cups for cream soup, and soup plates and oval spoons for clear soup. I have been busy trying to remember which of my guests I may have served incorrectly, and hoping that they either overlooked or were unaware of my gaffe.

GENTLE READER – The mistaken notion here is that mothers make mistakes. Yours didn’t. In fact, she spared you an additional complication: Bowls and cups are appropriate for luncheon, but only soup plates should be used at formal dinners. This makes it difficult to serve cream soup at night, which is a shame. (Miss Manners happens to prefer light soups at luncheon, which works because bouillon may be served in a cup with a small round bouillon spoon, but where does that leave the cream soup? Out in the cold, so to speak.)

Never mind. Fortunately for you, Miss Manners and your mother are the only people who remember these rules. Being gracious ladies, they make generous assumptions about extenuating circumstances, such as menu or cupboard considerations.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I understand that I place the dessert fork to the left of the dessert plate on which it arrives, and that I place the dessert spoon to the right of the dessert plate. But what about the finger bowl, which I’m all for—how many fingers may be placed in it, and which fingers, if any? Do I place my fingers in the bowl before or after I place it, with its hand crocheted doily, where the bread-and-butter plate used to be?

How do I use the dessert fork and dessert spoon at the same time? Which goes in which hand, and which brings the dessert to your mouth? What is the other piece of silver doing in the meantime: lying on the plate, or remaining in the hand? And in what position are the fork and spoon left when dessert is over? What position are they left in if I pause to take a sip of champagne? Tines/bowl up or down?

If there are no rules concerning these details, it is certainly time there were.

GENTLE READER – All right, sure. There already are. But by the time dessert rolls around, even the nosiest people are too tired to police one another. Probably any crimes you could commit would pass unnoticed, except possibly drinking up your finger bowl, and even that might pass as late night humor to perk up a flagging party.

When a formal dessert service arrives, consisting of a finger bowl on a doily, fork on the left and spoon on the right, you put the fork on the table, to the left of the remaining dessert plate, the spoon on the right, and pick up bowl and doily and place it to your left, just as you said. There should have been no bread-and-butter place there before, as they are not present in formal dinner service, but yes, that’s the position. (The necessity for doing this should not baffle the uninitiated. Any fool can see that something has to be moved if the dessert itself is not to be plopped down in the middle of a puddle of lukewarm water.)

At this point you may, if you must, dip your fingertips (all of them—except that most people miss the little finger, because it’s too short—but not the thumb) into the water, and wipe them on your napkin. Frankly, you haven’t been eating with your hands at a formal dinner, so most people consider the finger bowl purely symbolic and skip the actual washing.

It is not absolutely required that you use both fork and spoon, and if you pick one, it should be the fork unless there is an obvious reason—a runny dessert—to use the spoon. An unused utensil is left on the table. In using both, the fork remains in the left hand and the spoon in the right. This means that the fork is of little practical use, except possibly as a discreet pusher, but it is held on to nevertheless.

During pauses, the utensils are placed crossways, so the waiter won’t snatch away yummies you haven’t finished. For those who envision the plate as a clock, this is approximately 7:30, although the hands (which is to say, the tools you use to avoid using your hands) should meet somewhat below the center. Fork prongs down, spoon bowl up. When you are finished and they are left together, crosswise, the tines go up as well. Those who believe that European manners are snazzier than American, and encourage otherwise stalwart patriots to eat with their forks in their left hands through the meal, will argue that the tines should be left down. Don’t listen to them.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – My husband and I have a dear friend (I’ll call her Mrs. Frigg) who believes that the labels should be left on her crystal stemware. We have dined in some of the finest restaurants in the world, and have never noticed labeled stemware before. Mrs. Frigg is so adamant that the labels should never be removed from stemware, that I thought I would appeal to your judgment. Since a great deal of time has been absorbed debating this issue, we have agreed to abide by your answer.

GENTLE READER – Baffled about what could have propelled Mrs. Frigg so far from the basic tenets of taste and sense, Miss Manners has come up with the following hypothesis: Mrs. Frigg has been trying for years now to get those pesky stickers off, and hasn’t succeeded. She kept breaking her fingernails trying to pick them off. She tried soaking the glasses, only to find that the labels slid somewhat, but were as tenacious in their new locations as in the old. In desperation, she tried scraping one off with a knife, only to break the glass. Thoroughly fed up, she decided that it would be easier to convince gullible people, who already live in a society where it is customary to pay good money to wear T-shirts with advertising on them, that the labels belong there. As sorry as Miss Manners feels for Mrs. Frigg, she advises you not to fall for it.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – When dining casually with friends, white wine hides discreetly in its ice bucket, but a red wine bottle seems at home on the table. Is there any exception to the general prohibition of commercial containers from civilized tables? Somehow a bottle of wine seems different from a bottle of catsup or milk.

GENTLE READER – The wine is hiding in the bucket when dining out casually with its friends? Miss Manners thought it was one of the more playful guests.

Wine sure is different from catsup or milk. No doubt about it. Among the less obvious differences is the fact that wine is properly placed on the table in its original container. All right, not the barrel, but the bottle (or the truly original container—the grape). You may use a wine coaster, or one of those thingamabobs that attach a handle to the bottle, if you wish. You may even decant it, if you have an excess of large crystal containers. But it happens that while putting a milk carton or catsup bottle on the table is a high etiquette crime, disguising the wine bottle is considered excessively genteel. Go figure.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – At a dinner party, I was surprised to see the hostess serve the soup first and then a delicious salad before the main course. I may be wrong, but I always served the salad first and then the soup. I’m sure it really makes no difference, but I would appreciate your opinion.

GENTLE READER – What happened to the oysters? Oysters are supposed to be the first course. Or terrapin. Then the soup, then the fish, then the mushrooms or asparagus, then the roast, then the frozen punch, then the game, then the salad, then the creamed dessert, then the frozen dessert, then the cheese, then the fruit, and then hungry guests can get into the candy and nuts.

At least this was the traditional order of dinner back when meals were meals. A lot of funny notions about nutrition and health have come up since then, which is why Miss Manners no longer insists on that order (as if she could stand up against the fierceness of the food fanatics, if she tried). Most of these courses have been eliminated, and the standard formal meal is soup, fish or meat (but occasionally still both, as separate courses in that order), salad, dessert and/or fruit.

Often, nowadays, people will start with the salad because they have picked up the habit from restaurants, where formal service has been altered for the practical consideration of staving off hunger while the main course is cooked. Others start with salad for health reasons. Miss Manners does not object, provided she doesn’t have to listen to the lecture about why.

“Have something more to eat,” the genial host urges the reluctant guest. “Have another drink. Because if you don’t, I will badger and humiliate you until you’ll wish you had.”

That last remark is not actually spoken. But Miss Manners can perceive an implied threat from a certain tone and persistence, and so can those who find themselves the hapless victims of forced hospitality.

Against their judgment and their desires, supposedly pampered guests consume items they don’t like, want or believe are good for them, and in quantities not of their own choosing. They will do this, mistakenly, in the name of etiquette.

Actually, etiquette has no interest whatsoever in making people turn green and rush out of the room. On the contrary. It is puzzled that guests, as well as hosts, harbor the strange notion that force-feeding people more refreshment than they seem to want constitutes politeness, and that holding out against this campaign is rude.

Miss Manners has no brief for the modern adult version of the food fuss. Those who go around telling their hosts not only their own likes and dislikes, which is bad enough, but their beliefs—that this or that food will damage either your body or your soul—don’t even pretend to be polite. They believe that a good cause always justifies making everybody miserable. Perhaps this creates a desire to find a non-criminal way to stuff their cheeks so that they are unable to talk.

Nevertheless, Miss Manners staunchly defends the right of grown-up people to choose what they eat and drink and what they don’t, and if they base their choices on health, moral or religious choices, rather than mere prejudices, all the better. It is no etiquette violation to be selective, as long as one doesn’t make extra demands on one’s host’s patience, energy or dignity. Exercising this right is not easy when the food pushers are at work. Their endless patter of coercion—“Oh, come on, one won’t hurt you, I made this especially for you, it doesn’t have any calories, you’re too thin anyway, it’s good for you, you’re not going to make me eat leftovers tomorrow”—often succeeds in driving people to drink and chocolate.

What do these hosts have in mind? Do they really measure social success by intake? Do they believe that guests are terminally shy people who would starve to death for fear of seeming enthusiastic? Do they overestimate the amount of food that even hearty eaters could possibly consume?

Whatever the reason, Miss Manners asks them to cut it out. Politeness consists of offering food and drink without cajoling or embarrassing people into taking it. (It is a nice point of etiquette that reofferings never include a count: One does not say, “Oh, have another helping,” but, “Would you like some pie?” Such offers, if accepted, may be repeated as long as the pie and the guest hold out, but the wording is the same.) So is the wording of refusal. The phrase is “No, thank you,” and no guest should have to defend his or her choice. If a host is so rude as to argue, the guest should just keep repeating the polite refusal until the host is discouraged or Lent has arrived, whichever comes first.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – When dining at the home of a friend, is it rude to ask to warm up your dinner briefly in the microwave? I like food to be hotter than most people do, and I do this myself at home, but am reluctant to inflict this preference on a hostess, even under very informal circumstances.

GENTLE READER – One of the hardships of social life is that people who eat out at one another’s houses don’t always get exactly what they want to eat, exactly the way they want to eat it.

The trade-off is supposed to be that they get to be with their dear friends, who have tried to please them, even if they haven’t succeeded. Miss Manners is dismayed that an increasing number of people don’t seem to think that this is worth it. They can eat at home, but they cannot make special orders, and they cannot go into the kitchen to make adjustments. So no, you cannot zap your food when you dine out. Your reluctance was your own good sense of manners kicking in.

Etiquette has gone quite far enough in requiring hosts to provide salt and pepper so that guests may season the food to their own taste. Some of them turn unreasonably morose when they see the salt and pepper used, interpreting it as a reflection on their cooking. Miss Manners appreciates your help in not encouraging such tendencies. You really don’t want your hosts running around grabbing everybody’s filled plate back saying “Is yours cold, too?”

DEAR MISS MANNERS – My son-in-law says the hostess is supposed to take the first bite of a dessert. I say (coming from my grandmother from the South, who was rigid on manners and protocol) that the hostess always takes the first bite at the beginning of the meal, as well as dessert. I must say, I find the people here very short on manners.

GENTLE READER – Evidently, if you would rather quarrel than sit down quietly and consider that both of you could be right. So are any relatives you have who maintain that the hostess takes the first sip of soup, the first taste of spaghetti, salad, and so on.

Miss Manners doesn’t doubt that people can spin all kinds of stories about waiting for the first taste in case the hostess keels over from poisoning, but the present purpose of the custom is to indicate that it is now time to dig in to that particular course. If she is delayed from eating, or does intend to poison her guests, saying “Oh, please go ahead” will do just as well.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – For a casual supper with three other couples who meet on weekends to play cards, I baked an apple pie and brought it along. I had just started a diet program and did not intend to have any dessert myself. When my husband and I walked into their kitchen and the hostess saw my pie, she said, “Oh, you’re not going to have any pie, but it’s all right for the rest of us to eat it!” Meaning we can gain weight, but not you.

I was shocked at her lack of graciousness, and blurted out that she could throw the pie out instead of eating it. I might add that everyone ate some pie and complimented me greatly on how wonderful it was—including the hostess’s husband, but not her. She never did say a thing. What would have been a better response to her callous remark?

GENTLE READER – Neither you nor your hostess distinguished herself in this encounter, and Miss Manners is only relieved that it ended without a food fight. Had you wanted to make the point graciously, you could have replied, “I wanted to give you some pleasure, even if I couldn’t share it. Surely you don’t have my weight problems.”

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I love giving dinner parties—special parties, about twice a year, with great food, live music and entertainers. But as soon as the guests have had their dinner, they thank me with a nice smile and say bye-bye.

I’ve noticed that when we are invited to other dinner parties, guests tend to do the same. As soon as their bellies are full, they all retreat. Don’t you think that this is abominable behavior? I believe that to stay a little longer after eating and meet other guests is a polite way to show their appreciation to the hosts for being invited.

GENTLE READER – Yes, yes, it’s abominable, but it’s the coffee.

Oops. Miss Manners did not mean to suggest that your coffee was abominable. Excuse her while she thanks you with a nice smile and rushes out the door and off the face of the earth. What she meant was that the nice old-fashioned habit of serving after-dinner coffee in the living room gave guests somewhere to go to continue the socializing after they left the table. If you, like many hosts, have dropped that custom in favor of serving coffee at the table, there is no signal that guests may stay once they have finished the meal.

After dessert, ask “Shall we go into the other room for coffee?” and Miss Manners is sure everyone will follow you and settle down for more cozy chatting. You will be writing back, not only to express your gratitude, but to ask her how you can now get them to go home so you can go to bed.

Young people’s parties are too dark, too noisy and too loosely organized.

Is this the complaint of a curmudgeon whose own idea of socializing is scandalously tame? Well, yes. Personally, Miss Manners tends to favor mild encounters where even the glow of candlelight is tempered by silken shades, voices are modulated (often in obverse proportion to the explosiveness of the conversation) and guests are never allowed to outnumber the available soft chairs.

But far from grudging the socially restless their pleasures, Miss Manners worries that their parties do not adequately serve the intended purposes, let alone the wider objectives of their social life. It is not that the form is offensive—but that it is counterproductive.

As Miss Manners understands it, a typical such party has no fixed times, no fixed guest list and no fixed refreshments. People wander in throughout the evening, in pre-formed couples and groups that do not necessarily correspond to the acquaintance of the hosts, and these guests are accompanied by at least part of what they expect to eat or drink, or to trade for sustenance. Hosting duties are therefore minimal, especially since they no longer even require opening the front door and saying hello. That is done by anyone who happens to be passing by when the doorbell rings, if, indeed, the door has not been left invitingly open.

Announcing the date, providing a table on which offerings can be set and sweeping up the breakage is about it. Guests, too, have minimal obligations. Without advance commitment, they can drift in—or skip the whole thing—as they choose, and use it to entertain their own friends.

Here we have no-fault hospitality. Even Miss Manners could not work up the energy to insist that thank you letters are due when participants and hosts may never actually meet, at least so as to be able to recognize one another in broad daylight.

If the purpose of partying were to find inexpensive venues where pairs or groups of friends could enjoy themselves without regard to others, Miss Manners would acknowledge that these parties work. As a sort of disco scene run on a cooperative basis, it certainly cuts down the cost when, instead of buying supplies at the necessarily inflated rate of a commercial establishment, the clients supply their own. But—as Miss Manners hears, in plaintive tones from those who attend such events—music, atmosphere and drinks are not all that they want. They want to meet people. There remains a vestigial social feeling that it is better to meet new people at the homes of people one already knows—or whose friends one already knows; or whose friends of friends—than to pick them up in a public accommodation.

That young people have a great need to encounter huge numbers of their contemporaries before they settle into domesticity is something of which society has never been unaware. One might say that society’s existence is owed to this need. Certainly disposable-income parents have said so for years, as they were grudgingly yanked from the comforts of their own hearths to put on debutante balls and other devices to assist the young people in leaving their herds for couplehood. As the stiffest dragon running such an event realized, strangers must be able to meet. If they arrive in couples, or in their own groups, they have little chance of meeting anyone new. If no one performs the host function of making introductions, few self-introductions will be made.

Lights dim enough for romance should nevertheless be sufficient for people to be able to discern the facial lineaments of those they encounter. Music pervasive enough to cover awkward pauses must nevertheless allow for the understanding of introductions. If there is no order about taking food and drink in common, thirst and hunger may be satisfied without any incidental satisfaction of other appetites.

If young people want to meet new romantic possibilities, Miss Manners suggests that it may be well worth the trouble of organizing a party in which a goodly number of people attend alone, eat and drink together and can see and hear what they are doing.

Here is an invitation that many people receive from people they love (and believe they are loved by):

“I’m giving a party. If you feel you must put in an appearance, please make it brief. And for heaven’s sake, don’t say anything embarrassing. But can’t you find something else to do that night? I’d really rather you weren’t there at all.”

Why the recipients of such invitations humbly refrain from noticing how rude they are, Miss Manners does not understand. The fact that the spurned guests happened to have brought up the hosts may have something to do with it. Still, she is astonished that many parents not only allow such an invitation to be issued to them but accept its terms.

Miss Manners admits that one has to admire the skills of teenagers who were able to resurrect that defunct adage “Children should be seen and not heard” and use it with equal force in the opposite direction. Even more impressive is the way the last few generations—including some who have now graduated to being parents—managed to establish the idea that teenagerhood is such a different culture from the adult society’s that the very people who reared teenagers are the least capable of understanding them or evaluating their actions.

This does not, however, work the other way. Oddly enough, considering that the parents have all been children and none of the children have been parents, the children still seem to claim the right to judge their parents. It is just they who prefer to be ruled by their peers. The unsubstantiated argument that everyone else does something is considered a persuasive one.

Miss Manners thoroughly understands why such arguments are made. Finding that a child docilely accepts all limitations may not be immediate cause for calling the pediatrician, but it should be watched. Allowing this case to be developed as ingeniously as possible is excellent practice, especially for those who hope to rear lawyers.

She just doesn’t understand why any parent would buy the idea that he or she has impaired judgment. It’s a short way from there to being told that they dress funny. Once successful, the premise extends to parents being embarrassing by their very existence—nobody else has visible parents. Certainly not at a party.

Miss Manners is not suggesting that the parents actually join their teenaged children’s parties—only that they not be run off the premises. “Putting in an appearance” doesn’t even have to consist of helping the hosts greet their guests (and thereby frightening the guests into thinking it will be a mixed-generation party).

Ideally, the parents appear in the party room when most people are there, and greet them—well, as if they own the place. That is, they look like the same warm and confident selves they would be to their own guests. They may then retire, but at least once or twice during the evening, should stroll through again on a normal household errand—to get a book from downstairs, for example, or a snack from the party food—and have a few pleasant words with the guests. This is not only to police the activities, as their children will immediately charge and the parents will deny, although that is not out of the question. A pleasant police officer strolling his beat and greeting everyone by name may save himself or herself rougher duties later. Even the hosts may not be sorry to know that a parent is available to play the role of the heavy when they themselves cannot cope with uninvited or misbehaving guests.

The more presentable reason is that they actually like meeting their children’s friends and want to make them welcome. Besides, it’s their house. The pattern to use—and to ask the children to recall—is how they were treated when they were small and an adult party was being held. Although not invited to join the dinner party, the children were allowed to make an appearance at the beginning of the evening, before trotting off to bed, and one or two later trips downstairs were more or less tolerated. It’s time to collect on that.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – It seems to be a state law here that the parents of each graduating high school senior hold an open house to which they invite every name in their Rolodex. I have been invited to open houses by people whose children I have never actually met. (Invitees can buy their way out with a congratulatory card enclosing a check for $25 or so. When the parents send out a couple of hundred invitations, these can add up to a tidy pile.)

When I am invited to a party for a child I have known and been fond of since birth, I go to commemorate the end of an era. Here is what happens:

I hand the card and enclosed check to the graduating honoree. He accepts it with a grunt, looking away so as not to make eye contact, and deposits it in a basket. He then eases off to rejoin his friends, and for the rest of the party will studiously avoid social contact with any of the adults present. I have never seen an adult at one of these affairs who looked as if he or she were having a good time. After a couple of hours, one is allowed to leave, unless one is a grandparent, in which case one must stay the entire time and chat up the procession of total strangers.

I am determined not to put people through this. Would it be all right if I gave a party for my son’s friends only? I don’t want to be remiss in meeting my social obligations, but I will be very happy if Miss Manners allows me to skip this one.

GENTLE READER – From your description, it sounds as if you will not be the only happy person. To resolve not to invite people to have a bad time is a good idea.

Miss Manners questions why these parties are so awful. In theory, multigenerational celebrations ought to be a lot of fun. Those who don’t think so need only send their congratulations—there is no charge for declining an invitation.

From your description, these parties falter from a shocking lack of manners on the part of the hosts and the guest of honor. It’s not only a matter of the child’s showing gratitude. He and his parents have an obligation to socialize with all their guests and introduce them around.

So, while Miss Manners is willing to let you off the hook, she would like you to reconsider. As great a contribution to the social happiness of the community as it would be not to give the party, you could make more of a contribution by giving a good one. This would require involving your son in the planning, and teaching him how to be a good host—training that will be valuable to him throughout life. You cannot hope to bring this off without his enthusiastic participation, but you might be able to prod him into showing some imaginative interest.

The first rule of children’s birthday parties is that they shouldn’t scare the daylights out of the children. Miss Manners would have thought this obvious to all parents of small children, and parents of small children happen to be practically the only people mad enough to attempt to give parties for small children. Apparently it is not obvious. Violating this rule seems to be the first object of those who can afford it. The now popular adult fantasy about the ideal children’s party—with an army of entertainers, trained animals, electronic wizardry, fancy catering and crowds of guests creating avalanches of presents—does a thorough job of terrorizing both nominative hosts and their guests.

Miss Manners is afraid that grown-ups forget what (besides alcohol) makes them enjoy huge bashes: It is the thought that they are getting fed and entertained for free. As people who are used to being fed and entertained for free, young children prefer to be the agents of noise and confusion, rather than merely its victims.

The classic children’s birthday party, with its rule about the number of guests being the same as the age of the birthday child, and its cake-and-games routine of highly-supervised bedlam, tends to be more successful with the guests than the big-and-scary parties that so impress their parents. This brings Miss Manners to her real interest in the matter, which concerns the second—one would also think obvious—rule about children’s birthday parties: that one must never allow the child to expect to be, even for a day, the center of the universe.

Mind you, Miss Manners is all for pleasing one’s children and giving them special treatment on their birthdays. That their wishes should be studied and, when reasonable and possible, indulged is not what disturbs her. It is the notion that this glory momentarily cancels the necessity of their considering others’ feelings and suspends the etiquette rules connected with this. Miss Manners considers this illusion worse for them even than the foodstuffs they picked out for the day’s menus. As expectations of total control can never be realized, believing that one deserves this leads to a lifetime of birthday grudges. Relatives and friends who may try to divine and fulfill all birthday wishes are bound to encounter resentment when they happen to guess wrong or not do enough.

This is an attitude that gets decidedly uglier with age. The weddings of people brought up on this expectation of perfection are a public menace. Schooled in birthday selfishness, they go around screaming “But it’s our wedding and we can do whatever we want!” as an excuse for spending other people’s money, manipulating their behavior, ignoring their wishes and generally abandoning the obligations human beings must have to one another if we are to live in relative peace.

So rather than using a birthday party as an occasion for promoting piggy behavior, proper parents use it to teach the extra duties that a host has for the welfare of his guests. That being the center of attention creates responsibilities to others is a hard lesson, but a crucial one.

It starts with the guest list. Any thinking child sees this as an opportunity to settle scores, rather than obligations. A polite parent insists that guests must include those who might reasonably expect to be invited (because the guest attended their parties, or because the entire rest of the class is), not only people who happen to be in favor at the moment.

Guests must be greeted at the door, included in whatever activities take place, offered refreshment and shown gratitude for their generosity, even if they are trying not to let go of the presents they have brought. Contrary to all juvenile power of reasoning, present-giving must be handled so that it gratifies the giver as well as the receiver. Teaching someone to thank everyone enthusiastically, without regard to one’s actual personal opinion of the item given, is another of those unreasonable but essential lessons of civilization.

The most horrifying of innovations Miss Manners has heard is the idea that the guest of honor—the birthday child, but later in life, the bride-to-be at the shower—gets a kickback on any prizes won. Favors and prizes are intended for guests. They are there to be shown a good time, not to kowtow to the host. Children who learn that are going to have a better chance of getting from one birthday to the next.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Children’s birthday parties have changed a great deal since I was a child. Professional entertainment has replaced musical chairs, expensive goodie bags have replaced hats and streamers, and elaborate theme cakes rival those at weddings.

This is all well and good for those who can afford it. But one change troubles me deeply: No longer does the birthday child open his or her gifts with their guests present, oohing and ahhing over each acquisition. Am I old fashioned (I am only 35) to think that this is not only rude but unfair to all of those who participate in the party?

My children, ages 3 and 6, go to a great deal of trouble to pick out their friends’ birthday gifts. My oldest child cruises the aisles looking for the perfect gift for Betty Birthday (“she loves horses, but she can’t read yet, but she likes to play games, but only those kind of games where more than two can play, and her favorite color is pink, but not hot pink, and oh yeah, she really wants only Barbie stuff, but no hot pink Barbie stuff …”). Even my three-year-old wants to find the perfect gift for her friend, the one that will make the birthday child happiest. They both understand, as most children I believe do, the spirit of the old adage “ ’tis better to give than to receive.”

But here’s what happens: They arrive at the party and the proffered gift is snatched out of their hands as if it’s admission to an event. Two hours later the party is over, the guests are ushered out the door, goodie bags in hand as the brightly wrapped gifts are gathered up into large plastic garbage bags to be spirited away.

My children are disappointed because they didn’t get to see the reaction on the child’s face on opening the gift so carefully chosen. And what about the gifts from other children? They want to see those too. Then there’s the birthday child, denied his chance to be the center of attention (particularly since the clown kind of overshadowed the singing of “Happy Birthday”).

Later, we do get a “thank-you note,” usually written by the parent but totally illegible and therefore not very meaningful to a three-year-old. (On the other hand, an exuberant “It’s exactly what I wanted!” from the birthday child is worth millions.) Sometimes the cards get separated from the gifts in those big plastic garbage bags and we never receive an acknowledgment.

The arguments for this practice that has become so prevalent include:

What do you think? I miss those days when the opening of the presents was the highlight of the party.

GENTLE READER – The very ritual you miss is responsible for souring Miss Manners on children’s birthday parties in recent years. She has seen the concept that one can gather people for the purpose of showily receiving their offerings turn into the defining event of people’s lives.

People who experienced it and liked it, those who experienced it and felt shortchanged, and those who never experienced it all want to re-create this moment. That is a lot of people giving themselves birthday parties all their lives and demanding similar treatment on every other occasion they can dream up.

But she has always believed, as you do, that what legitimizes children’s birthday parties is the opportunity to teach unreasonable social skills, such as letting go of a present one has brought, or pretending to like something one already has. For that alone, she is willing to support the present-opening ritual.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Our social circle includes friends and acquaintances with small children and recently we have been invited to a number of birthday parties for children as young as two and three years old. These are not just small gatherings for the family and closest friends. For example, my husband’s former colleague called to invite us to his two-year-old daughter’s birthday.

We opted not to attend, but weren’t sure what to do. Do we send a card with best wishes to a toddler? Are we being too cynical, or is it indeed perfectly acceptable to organize such events?

GENTLE READER – Do you do business with these two-year-olds? Not that Miss Manners would justify toddlers’ entertaining their professional acquaintances at their birthday parties. She is only inquiring because you do not seem to fit any of the proper categories of birthday party guests—the celebrant’s friends, relatives and others (who may include parents’ friends) who have demonstrated that they dote upon the honored one.

So why were you invited? While Miss Manners can guess at the nature of your cynical speculation, she does not really think that parents go after you in order to secure yet another stuffed animal. Rather, she suspects that they classify the entire world as people who dote upon their children. Many parents require remarkably little encouragement to do this. Think back—did you once say “My, what a nice baby”? That could have done it.

There is also a less charming possibility. A great many people do not think of their guests as people to be given a good time, but as supernumeraries in their own, or their children’s, pageantry. So they may have assumed that offering you food and drink was enticement enough, without their having to create an occasion that would also interest you. In either case, you need only decline the invitation with thanks and your best birthday wishes.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – One of my closest friends, who is a wonderful hostess and enjoys throwing her own parties, birthday and otherwise, has informed me that she planned to do the same this year. Then, two days ago, a friend of hers approached me with the idea of rounding up several of her friends to plan and give her a surprise birthday. I liked the idea, so I discussed it with a mutual friend, and we devised a plan that, with enough care, could be successfully executed.

My excitement quickly fizzled when I discovered that the guest of honor had “suggested” to the friend who approached me that he get some of her friends to throw a “surprise” party. She has since mentioned this (a hint perhaps?) to my co-planner who is as confused as I am as to why someone would intentionally plant the idea for her own surprise birthday party, instead of being straightforward and saying, “Will you, in lieu of a gift, help me throw my birthday party”?

I am more than willing to help her organize and execute her gala buying and preparing food, contacting guests, etc., but do not appreciate being encouraged to give a party that clearly will not be a surprise, as it is the guest of honor’s idea. If I am approached by her, however directly or indirectly, how should I tactfully respond?

GENTLE READER – Has your friend the great hostess ever given you a birthday party, surprise or otherwise? It is not that she was obligated to do so—Miss Manners is just hoping to eke out one little bit of pity for this pitiful person, and needs all the help she can get.

More likely, your friend is one of a growing number of people who refuse to leave the possibility of kindness in their friends to chance. So they are willing to undertake the burden of deciding how to pamper themselves, and of instructing others in how to carry it out. Thus the practice of adults giving birthday parties for themselves has spread wildly, along with the number of brides who direct their bridesmaids to give them showers, and graduates who instruct their relatives what presents to give them.

Your friend’s idea, of giving herself a surprise party, takes this to a whole new level. If she wants to leap out of hiding and shout “Surprise!” at herself, why does she need to involve so many intermediaries? Still, she is one of your closest friends and, you attest, a wonderful hostess. So Miss Manners will try to think of her as someone who is gallantly trying to make up for being slighted by life, and whose friends are willing to make up for that perceived neglect.

May she suggest just a gentle way of reminding your friend that she would be better off trusting her friends’ affection than attempting to pre-empt it? You could just run to her and say in a devastated tone, “Oh, we wanted so much to give you a surprise party—but I hear you knew all about it. We’re so disappointed. Now we want you to forget I said anything, so that some other year we can go ahead and really take you by surprise.”

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Do I set up a table for gifts at our 25th anniversary (we will be reciting our vows and have a reception afterwards)? Do they bring gifts for this occasion? Or would it be proper to put “cards and gifts optional” on the invitation?

GENTLE READER – Optional, as opposed to what? As opposed to “Cards and gifts are mandatory, and steps will be taken to collect from those who do not contribute”?

Presents are always optional, and it is not the place of people who happen to be celebrating an anniversary, or any other occasion, to expect them—not even by attempts to discourage them. If “No gifts” gives people the idea that their hosts are pointedly dwelling on the idea (and it does, it does), Miss Manners can only imagine what your wording would suggest.

Some people will probably bring presents and some not. It is your obligation to lessen any embarrassment on the part of the latter, as well as to show appreciation to the former. This would best be done by setting aside whatever presents are brought, ideally with the unobtrusive assistance of a close friend or relative who can discreetly write the giver’s name on each package, in case cards are missing. After the festivities, you can then write them letters of thanks. If you have a table to store them, please make it inconspicuous, so that it doesn’t seem to serve the purpose of a ticket-taker’s booth.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – My parents will soon be hosting their 50th wedding anniversary party for about 150 guests, most of whom their children do not know. They have planned, as the entertainment, that each of their children, as well as their children’s spouses, provide a few remarks on what it’s like to be a member of the family.

My brothers and sisters and I do not feel this is a good idea for several reasons. This might not be very entertaining for those assembled (as it might be for an all-family gathering), but, more importantly, our immediate family hasn’t gotten together in almost 20 years (we each live in different cities) and thus our shared memories in recent decades are non-existent.

Do you think it a good idea? Is there some other form of acceptable entertainment at these events? The only anniversary party I’ve been to with entertainment was when a couple who were professional performers sang several sweet songs in honor of the anniversary couple. This was sweet and light and well received.

GENTLE READER – Miss Manners agrees that it is a terrible idea to put the children on the spot and bore the guests. She also begs you to consider the state of mind of people—your very own parents—who would go to the extreme of coercing their children into making public testimonials to them.

The fact that the family hasn’t gotten together in twenty years only makes it the more poignant. Your parents are rather in the position of children who want to force divorced parents to pretend to be a couple, just for the occasion of their own wedding. They want to nudge you to behave like united and devoted children in front of their friends.

Anniversary parties do not need special entertainment; the guests are supposed to be sufficiently entertained by enjoying sociability with the couple and others who care for them. Yet toasts would be in order. Miss Manners suggests that you children interpret the parental wish by offering several brief but effusive toasts to your parents. It might also be a good idea for you to supplement these individually with letters of reminiscence and affection. If your parents choose to share these later with their friends, at least you won’t have to be a party to watching the display.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – Our seven children gave us a beautiful catered 40th anniversary party, and all our relatives—my husband has three brothers and I have five sisters and one brother—came. Now they want to give us a 50th party. I say it is in bad taste to have two such parties and have all the same people show up. Not one of our nieces or nephews have given anyone else a party, although they are grown and have the money.

GENTLE READER – Have the party. Miss Manners’ rule is that adults get three all-out parties per half century—say the 60th and 75th birthdays, or the 50th and 60th anniversaries—and as many smaller gatherings for which their intimates have the enthusiasm. She’s going to count your 40th and 50th anniversaries for your first half century, so you can have a 60th and a 75th as well.

Whether this seems to show up your siblings’ children is not for you to ponder. Miss Manners prefers to believe that they enjoy these family gatherings all the more because they are the only ones.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – We are an international family on assignment from France to this great country for the past three years. We have come to appreciate American hospitality, and really enjoy the informality of backyard barbecues, play groups for children, yard sales, open houses, or just the good neighborly “come and drop by for a cup of coffee” event. However, there is one thing called SHOWERS that has me utterly confused, if not frustrated. Here is the scenario as I see it:

A young couple plans to get married. Friends, colleagues and (or) relatives give a bridal shower. I bring a gift or contribute to a collective gift coordinated by the host.

The same young couple gets married. I attend the wedding and bring or send a gift.

The same young couple buys a new home. Friends, colleagues and (or) relatives give a housewarming shower. I contribute same as above.

The same young couple moves into their new home in our neighborhood. We visit and bring a housewarming gift.

The same young couple is going to have a baby. Friends, colleagues and (or) relatives give a baby shower. I contribute exactly the same as above.

The new baby is born. We go and visit the young family and bring a gift.

Word is out that the same couple (not so young any more) is not getting along so well, and has filed for divorce. Friends, colleagues and (or) relatives give a divorce shower. I contribute the same way as described before.

Of course, I haven’t been to a divorce shower yet. But if they are not already invented, I am sure somebody will.

Exaggeratedly speaking, I could carry this on until the bitter end (i.e., funeral shower), but I think I made my point.

GENTLE READER – It is a point well taken. Americans, as well as their gracious visitors, are being drenched by unusually prevalent showers. (Please don’t make jokes about divorce or funeral showers. Every time Miss Manners recklessly exaggerates an already ludicrous situation, she is deluged with mail indicating that reality is way ahead of any joke one can make.)

In proper American etiquette, a shower is a lighthearted event among intimate friends, properly given only before a wedding and the birth of a first baby. Relatives should never issue invitations. If friends give them, they do so of their own free will—it is not mandatory for bridesmaids, for example, to throw showers. No one should be invited to more than one such event for the occasion. Presents should be mere tokens. Housewarming parties are given by the owners themselves, but the traditional good luck present is bread and salt.

However, we live in an age of greed and entitlement. The shower has been perceived as one more opportunity to turn a milestone to consumer advantage, and all these rules are being violated right and left. This should not discourage you from abiding by the rules of etiquette available to guests: You may decline the invitation, sending nothing more than your good wishes. Some of us used to think that that in itself was quite valuable.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – I am in the process of getting a divorce. I want to make a new beginning for myself and my five-year-old daughter. Since we will be moving into a new apartment and will be buying everything new, a friend suggested that I have a “divorce reception” (as opposed to a wedding reception) and register at department stores.

Is this proper, and if so, how would I let my guests know that I’m registered? Personally, I think I should have a house warming party.

I must add, I did not have the traditional wedding with reception, and most of everything we had belonged to my soon-to-be-ex-husband. Please help me out on this. I really try to go by “the book” on things like this.

GENTLE READER – The book says you don’t parody weddings by celebrating a divorce. Never mind that you might consider it a joyous event. You can hardly expect your daughter to witness your glee at having gotten rid of her father.

By all means have a housewarming party. First Miss Manners asks you to rid yourself of that sneaking feeling that you are entitled to be deluged with presents you forgot to collect upon your now-defunct marriage.

DEAR MISS MANNERS – A flyer was placed in my mailbox last week, which reads, “Julie and Dean invite you to a housewarming. Bring a covered dish and a lawn chair. Cash donations accepted.” It then lists their address and phone number and the date of the get-together.

I have never seen these people. I saw a moving van at the house one day when I drove by. I think these are neighbors I want to avoid at all times. My husband says that at least we know what kind of people they are.

I have never heard of anyone giving themselves a party, inviting strangers to come, and then asking for a cash donation. Are we wrong to find this offensive? Is this a normal thing now for people to do? Someone told me the latest thing going on is to have a birthday party and ask the guests to bring food. The hostess will furnish the cake and ice cream, and the guests bring the rest of the food. This is happening at children’s parties.