“Disease, Debility, Doubt, Inadvertence, Sloth, Sensuality, Wrong Understanding, Non-attainment of the plane and Instability, these mental distractions are the impediments— Pain, dejection, unsteadiness of limbs, inspiration and expiration are the companions of the distractions— For their Prevention, the practice of one truth— The transparency of the mind comes from the development of friendship, compassion, joy, and neutrality regarding the spheres of pleasure, pain, virtue, and vice respectively—”

— Bengali Baba, in The Yogasutra of Patanjali, pp. 15–17.

The next three chapters bring us to the heart of hatha yoga—to postures that involve backbending, forward bending, and twisting. Of these three, backbending is the logical place to begin our discussion because it is relatively simple. But the two categories of backward bending and forward bending postures form a pair: the muscles that resist the bend in one category are the same muscles that pull us into the bend in the other category, and we need to see and understand them in reference to one another. To keep the comparisons in perspective this chapter will be about 90% backbending and 10% forward bending, and the next chapter will be about 90% forward bending and 10% backbending.

The plan here will be to first sum up the possibilities for forward and backward bending in the standing position, concentrating on limitations in the hip joints and lower back, and then to build on our discussion of the vertebral column by examining the spinal limitations to backbending in more detail. Next, we’ll look at the relationships between breathing and backbending, and finally we’ll turn to the myriad forms of backward bending in hatha yoga, beginning with the famous prone backbending postures—the cobra, locust, boat, and bow—and continuing with more specialized postures such as the fish, the wheel, and the camel. Two more backbending postures, the arch and the bridge, are traditionally part of the shoulder-stand series and will be deferred to chapter 9.

Some of the postures discussed in this chapter are only for those who are in excellent musculoskeletal health. A few guidelines are given in the course of the descriptions, but if in doubt about whether or not to proceed, take note of the specific contraindications at the end of the chapter.

THE ANATOMY OF FLEXION AND EXTENSION

To understand any function, envision being without it. For example, we can see at a glance how vertebral bending, both forward and backward, contributes to whole-body bending by examining how someone would bend if their spine were fused from the pelvis to the cranium. This is not an academic hypothesis. One who has had such surgery for severe osteoarthritis will bend forward only at the hip joints, just like a hinged stick—arms dangling, head, neck, and torso stuck out straight and stiff as a board. And yet this person may be comfortable and relaxed enough to practically take a nap. He may be able to bend forward up to 90° and hyperextend to the rear about 10°—entirely from the hips.

THE HIPS AND BACK IN COMBINATION

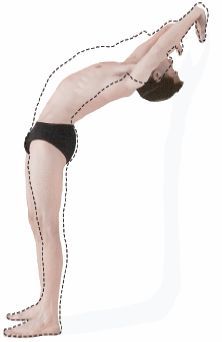

Hip flexibility in isolation is only of theoretical interest to us, at least for the moment, but the question of how hips and backs operate together for backward bending is eminently practical. Beginning with extremes, occasional circus performers—always women in images I’ve located—are able to extend their spines backward 180°, plastering their hips squarely against their upper backs. Images of 180° backbending can be seen in fig. 7.3 of Alter’s Science of Flexibility, as well as in a beautiful sequence of video frames 7–8 minutes into the tape of Cirque du Soleil’s Nouvelle Experience.

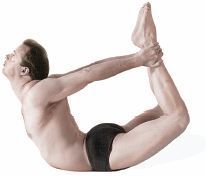

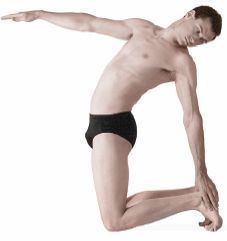

Maximum hip hyperextension appears to be about 45°, which is seen in occasional women who can drop down into the wheel posture and then scamper around on their hands and feet looking like daddy-long-leg spiders in a hurry. Both extremes—180° of back extension and 45° of hip hyperextension—are anomalous, and it is not advisable for anyone to attempt extending either the hips or the spine this much unless one’s profession requires it. Even highly flexible dancers, gymnasts, and hatha yogis rarely try to bend backward more than 90°, ordinarily combining 20° of extension at the hips with an additional 70° of extension in the lumbar region. In this case the right angle between their thighs and their chests is more than enough to permit them to touch their feet to their heads in advanced hatha yoga postures (fig. 5.12).

Figure 5.1. 120° flexion at the hips is a common maximum, and is enough for laying the chest down easily against the thighs when accompanied by moderate flexion of the spine.

Unlike the outermost limits for backbending, the outside limits for forward bending are all within a normal range for anyone with excellent general flexibility. Dancers, gymnasts, and hatha yogis, including both men and women, can often bend forward up to 120° at the hips with the lumbar lordosis arched and the knees straight (fig. 5.1). These same people may also be able to bend an additional 90° in the lumbar region, making a total of 210°. Since 180° is all that is required to lay the torso down against the thighs in a sitting forward bend (fig. 6.12), their full capacity for forward bending can’t be tested except by measuring hip and spinal flexibility separately.

Figure 5.2. A relaxed standing backbend with straight knees includes about 20° of lumbar bending and 10° of hip hyperextension for a total of 30°of “backbending.”

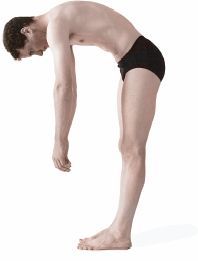

Next, let’s consider the limits of backward and forward bending in someone more typical, say a thirty-year-old male beginning hatha yoga student who has always been athletic and in good musculoskeletal health, but who has never shown an interest in any kind of stretching. He won’t be able to bend backward very far, and what he can do is hard to appraise because he will invariably bend his knees and exaggerate his lumbar lordosis in preference to hyperextending the hips. Without a sharp eye it is difficult to differentiate among these three components.

To assess this young man’s capacity for hip versus spinal backward bending as best we can, first have him warm up with an hour of vigorous hatha so we can see him at his best. Then, to make sure his knees do not contribute to the bend, ask him to do a relaxed standing backbend with his knees extended. His chest will probably be off vertical by only 30°, which suggests a combination of about 20° of backbending in the lumbar region with about 10° of hyperextension in the hips (fig. 5.2).

Forward bending in this same student is easier to evaluate. You can ask him to bend forward from the hips while keeping his lower back maximally arched. Then, just before his lumbar lordosis begins to flatten you can estimate the angle between his torso and thighs, which is likely to be about 30°. This represents forward bending at the hips (fig. 5. 3). Then ask him to relax down and forward to his capacity. If he can bend forward a total of 90°, which allows him to reach down a little more than halfway between his knees and his ankles, it suggests that has achieved the additional 60° of forward bending in his lumbar spine (fig. 5.4).

Figure 5.3. A moderately flexible young athlete can typically bend only about 30° at the hips while keeping a sharply defined lumbar lordosis (simulation).

CERVICAL, THORACIC, AND LUMBAR FLEXIBILITY

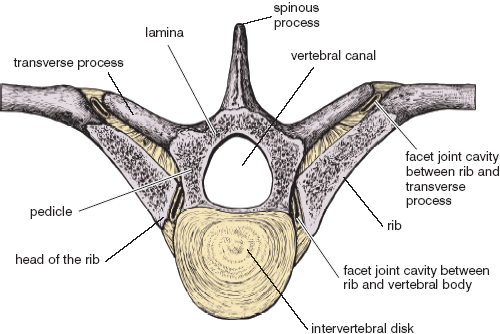

The spine’s flexibility varies from region to region. Starting with the neck, the cervical region is especially mobile. If you have normal flexibility, your head can extend backward on the first cervical vertebra about 20°, and you can flex forward at this same site about 10°. The rest of the cervical region can bend backward 60° and forward another 80°, in this case touching the chin to the sternum. We’ll look at these movements in detail, along with rotation, in chapter 7. Just below the seven cervical vertebrae, the thoracic region permits little forward or backward movement because the rib cage is too rigid. This means that most of the backbending in the torso takes place in the lumbar region between the bottom of the rib cage and the sacrum, that is, between T12 and S1. That’s where we’ll concentrate our attention.

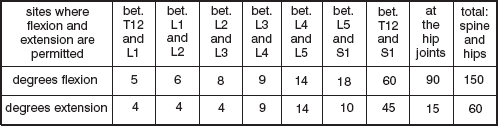

Young people with good flexibility who have been practicing hatha yoga regularly (Table 5.1) might reveal a total of 60° of lumbar flexion for forward bending and 45° of lumbar extension for backbending. This is in addition to hip flexibility, which we’ll say is 90° for forward flexion and 15° for backward bending. The knees, of course, must be kept straight to get accurate measurements. Someone with hip flexibility this good will be able to do an intermediate level posterior stretch (fig. 6.15) and will be able to arch back comfortably to touch their feet in the camel (fig. 5.35). If we break this down we can estimate the approximate mobility for flexion and extension that would be permitted between individual pairs of adjacent vertebrae (table 5.1).

Figure 5.4. Limited hip flexibility prevents this young man from reaching further down. This simulation reveals a combination of about 30° of hip flexion with 60° of spinal flexion for a total of 90° of forward bending. Such a student can and should bend the knees slightly to find a more rewarding pose, one that at least allows him to grasp his ankles.

WHAT LIMITS BACKWARD BENDING?

In chapters 3 and 4 we discussed the muscles and ligaments that limit backward bending in the hips. These include the psoas and iliacus muscles (figs. 2.8, 3.7, and 8.13); the quadriceps femoris muscles (figs. 1.2, 3.9, 8.8, and 8.11), especially the rectus femoris component (figs. 3.9 and 8.8–9); the abdominal muscles (figs. 2.7, 2.9, 3.11–13, 8.8, 8.11, and 8.13), especially the rectus abdominis (figs. 3.11–13 and 8.11); and the spiraled ischiofemoral, iliofemoral, and pubofemoral ligaments (fig. 3.6).

Turning to the torso, the main structural limitations to backbending in the thoracic region are the rib cage (figs. 4.3–4) and the spinous processes (figs. 4.6b and 4.7b), which extend so far inferiorly in the thoracic region that they quickly butt up against one another during extension. And in the critical lumbar region the first line of resistance to backbending is muscular—intra-abdominal pressure generated by a combination of the respiratory diaphragm (figs. 2.6–9), the pelvic diaphragm (figs. 3.24–29), and the abdominal muscles (figs. 3.11–13, 8.8, 8.11, and 8.13). As far as major skeletal and ligamentous restrictions to lumbar bending is concerned, there are four: the physical limitations of the vertebral arches (figs. 4.5a, 4.6a, and 4.12–13), the anterior longitudinal ligament that runs along the front sides of the anterior functional unit (fig. 4.13), the intervertebral disks, whose nuclei pulposi are driven anteriorly within the intervertebral disks (fig. 4.11), and finally, the superior and inferior articular processes (figs. 4.5–6 and 4.13b), which become tightly interlocked during extension.

It’s anyone’s guess as to which of these structures yield to permit 180° backbends in circus performers. It is possible, although I have not personally checked this out in anyone, that unusually mobile sacroiliac joints (chapter 6) might account for some of the capability of laying the hips down against the shoulders. In any event, after the bend is an accomplished fact the heavy spinous processes characteristic of the lumbar region (figs. 4.5b, 4. 10a, and 4.13b) are probably butting up against one another.

Table 5.1. This chart estimates the degrees of flexion and extension permitted between individual vertebrae between T12 and the sacrum in someone who is moderately flexible. With 90° of additional flexion at the hip joints, the total forward bending permitted between T12 and the thighs is about 150°, which amounts to about 2.5 times as much forward bending as backward bending.

WHAT FACILITATES BACKBENDING?

What limits backbending is generally straightforward, but if you were to ask what assists backbending, the answer would have to be, “It depends.” In standing backbends, as well as in passive supine backbends, which we’ll cover later in this chapter, the answer is gravity. Standing, you simply lean your head and upper body to the rear, thrust your pelvis and abdomen forward, and let gravity carry you into the backbend. If you bend backward naturally, you also bend your knees, and that is why you have to extend the knees fully to evaluate backward bending in the hips and spine.

Figure 5.5. Deep back muscles exposed in successively deeper dissections following removal of the upper and lower extremities. The erector spinae are by definition the combination of the spinalis, longissimus, and iliocostalis (Sappey).

In prone backbending we are lifting one or more segments of the body against gravity. In this case the bend is accomplished by the deep back muscles (which lift you actively by extending the spine) or by the arms and shoulders (which can support a semi-relaxed prone backbend in any one of several ways). As we saw in chapter 4, the erector spinae muscles are responsible for extending the spine. They run from the pelvis to the cervical region and are composed of a complex of three muscles on each side—the iliocostalis, the longissimus, and the spinalis (fig. 5.5). Continuing into the neck are the splenius cervicis muscles, and to the back of the head, the splenius capitis (fig. 5.5). These latter muscles, which are also known as strap muscles from their characteristic appearance, run longitudinally. Deep to them are small, short muscles that run more or less obliquely between the spinous processes and the transverse processes—the semispinalis (fig. 8.14), multifidus, and rotatores muscles. Deeper yet are the interspinales muscles between adjacent spinous processes, and the intertransversarii muscles between adjacent transverse processes (shown in fig. 5.5 but not specifically labeled).

It is obvious that muscles and gravity play major roles in creating hatha yoga postures, but anyone who has stood, lain, or sat quietly in a pose for a few minutes knows that something else is superimposed upon its equipoise. That something is breathing. A formal statement of the matter might run as follows: Under most circumstances of normal breathing, inhalations will either lift you more fully into a posture or create more tension in the body, and exhalations will either relax you further into the posture or reduce tension. From the perspective of the first four chapters of this book, we can now examine this statement with respect to backbending.

In whole-body standing backbending (fig. 4.19) we saw that it was natural to allow exhalation to lower you maximally to the rear (relaxing you further into the posture). Inhalation then lifts you up and forward (creating more tension in the body). We also saw that you could reverse this pattern on purpose by pulling backward more vigorously into the posture during inhalation (taking you more fully into the posture), and then relaxing and easing off the posture during exhalation (thereby reducing tension). We’ll see variations on these principles in all the remaining postures in this chapter. In every case the diaphragm either restricts backbending, which we’ll call diaphragm-restricted backbending, or assists it, which we’ll call diaphragm-assisted backbending.

DIAPHRAGM-RESTRICTED BACKBENDING

When you are breathing naturally, inhalation restricts a standing backbend and exhalation assists it (fig. 4.19) because the diaphragm increases intra-abdominal pressure as it presses the abdominal organs inferiorly during inhalation. As we saw in chapter 3, it does this in cooperation with the abdominal muscles and the pelvic diaphragm: the increased intra-abdominal pressure restricts the bend by making the torso a taut, solid unit, thus protecting the critical lumbar region by spreading the vertebrae apart hydraulically and easing compression on all the intervertebral disks between the rib cage and the sacrum.

A simple experiment demonstrates diaphragm-restricted backbending. Stand up straight and interlock your hands behind your head, take a deep inhalation, and hold your breath while keeping the airway open. Then pull to the rear as hard as you can by tightening the muscles on the back of the body from head to heel (but don’t pull your head back beyond the natural arc created by the torso). If you have taken a deep breath and your respiratory diaphragm is healthy, you’ll feel the diaphragm stop the backward bend almost before it gets underway. Next, let just a little air out, and notice that your efforts to pull to the rear will be met with less resistance. Keep the airway open to make sure it is the respiratory diaphragm, acting in combination with the abdominal muscles, pelvic diaphragm, and the hydraulic nature of the abdominopelvic cavity, that is restricting and then easing the backbend. Increasing pneumatic pressure in the chest by closing the glottis would eliminate tension in the diaphragm and invalidate the experiment.

A propped backbending stretch will illustrate the same phenomenon. Stand with your back about two feet from a wall, and swing the hands overhead and backward to make contact. Adjust the distance so that you are in a comfortable backbend. Work the hands down the wall until you are just short of your comfortable limit of extension, but keep the knees straight. After you have relaxed and made yourself comfortable in the posture for 10–20 seconds, notice that each inhalation will diminish the bend in the lumbar region and straighten the body as a whole, and that each exhalation will allow your back to become more fully arched. More specifically, inhalation does two things: it pulls the thighs and legs slightly to the rear, and it lifts the chest and shoulders up and forward (fig. 5.6). It is easy to prejudice these results, however, and a fair test of diaphragm-restricted backbending requires that you keep constant tension in the upper extremities at all times and search out your most natural inclinations for bending and breathing. As we saw in chapter 4, you can easily reverse the results by purposely pressing more deeply into the bend during inhalation and then consciously easing off during exhalation.

DIAPHRAGM-ASSISTED BACKBENDING

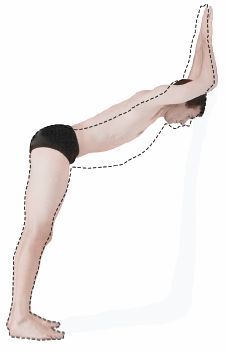

You can feel the opposite phenomenon if you face the wall, bend forward from the hips, and support the bent-from-the-hips posture with your forearms. Keep the lumbar region arched forward, making the posture a backbend from the hip joints up (fig. 5.7). Breathe in the posture and watch carefully. The most natural result is that inhalation deepens the backbend and that exhalation eases it. Keep the abdominal muscles relaxed during inhalation. If you tense them the dome of the diaphragm can’t descend very far, and you will lose the sense of being able to assist the backbend with inhalation. If there is any question about the results, aid exhalation with the abdominal muscles, and this will immediately and markedly diminish the lumbar lordosis (chapters 2 and 3). As with the propped backbending stretch facing away from the wall (fig. 5.6), you have to keep all conditions constant except for respiration. You can always pull yourself down consciously during exhalation to increase the lumbar bend, but that misses the point. Here we want to examine the effects of inhalation and exhalation in relative isolation.

The mechanisms underlying diaphragm-assisted backbending are straightforward. First of all, the depth of the backbend has been defined initially by the position of the feet on the floor and the forearms against the wall. This means that the abdominal muscles do not have to be tensed to keep you from falling, and it also means that intra-abdominal pressure will not be as pronounced as in a free-standing, internally supported backbend (fig. 4.19) or in the propped standing backbend (fig. 5.6). What is more, since the rib cage is relatively immobilized by the arm position, the crura of the diaphragm can only pull forward on the lumbar lordosis during inhalation to deepen the backbend. It’s a three-part situation: the static body position defines the extent of the backbend in the first place, decreased abdominal tension and pressure allows the diaphragm to deepen it, and an immobilized rib cage requires the diaphragm to deepen it.

Figure 5.6. Diaphragm-restricted backbend. Inhalation pulls the legs and thighs slightly to the rear, lifts the chest and shoulders up and forward, and increases intra-abdominal pressure, all of which combined straighten the body as a whole and diminish the backbend.

One more variable determines whether the diaphragm assists or restricts backbending in general, and that is how much the lumbar region is arched forward on the start. If students are stiff and wary, the arch will not be pronounced, the abdominal muscles will be tensed, and inhalation will create more stability, thus restricting the bend. That is what we usually see in beginning classes. With stronger and more flexible students, inhalations are more likely to increase the backbend, deepening it in proportion to how readily they can release intra-abdominal pressure and allow the iliopsoas, rectus femoris, and rectus abdominis muscles to lengthen. As we experiment with the prone backbending postures that follow, keep all possibilities in mind: notice that the descending dome of the diaphragm will either maintain restrictions in the torso and create diaphragm-restricted backbending, or, depending on the student’s flexibility and on the positions of the upper and lower extremities, the diaphragm will force the front of the body forward during inhalation and deepen the bend.

Figure 5.7. Diaphragm-assisted backbend. In this forward bend from the hips, inhalation increases the depth of the lumbar lordosis provided the abdominal muscles are kept relaxed. The relaxed position against the wall permits the abdominal muscles to come forward and allows inhalation to occur freely, in contrast to the case of diaphragm-restricted backbending that is illustrated in fig. 5.6.

Of the many forms of backbending postures, the prone backbends—the cobra, locust, boat, and bow—are the most widely practiced in hatha yoga. In contrast to standing backbends, in which gravity assists your movement into the postures and resists your efforts to come up, in the prone backbends you lift parts of the body away from the floor against the pull of gravity and then return to your starting position with the aid of gravity. Prone backbends are harder than standing backbends because you are trying to overcome the resistance of connective tissues and skeletal muscles on the front side of the body while simultaneously opposing the force of gravity, but they are easier because coming out of the postures does not have to involve anything more than dropping slowly to the floor.

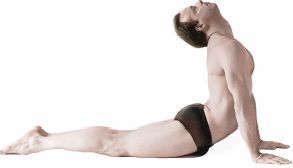

The cobra posture is named for the manner in which the magnificent king cobra lifts its head and flattens out its hood in preparation for striking its prey. It is probably the most well-known prone backbending pose in hatha yoga. Considered along with all its variations, it is worth the attention of everyone from beginners to the most advanced students.

Every variation of the cobra and its close relatives begins from a prone position and ends with the neck and back extended. In contrast to the caution we exercised in extending the head and neck in standing backbends, we have no reason to restrict that movement here, and we can work confidently with the cervical region without being concerned about losing our concentration on the rest of the posture or getting lightheaded from cardiovascular responses. Other characteristics of the postures vary. Depending on the specific exercise, from the top down, you can start either with the forehead or the chin on the floor, the deep back muscles either active or relaxed, the hip and thigh muscles firm or relaxed, the knees extended, relaxed, or flexed, and the feet together or apart.

THE CLASSIC BEGINNING COBRA

To introduce the series of cobra postures, we’ll begin with the classic beginning pose even though it is not the easiest one. Start with the hands alongside the chest, with the palms down, the fingertips in line with the nipples, the heels and toes together, and the elbows close to the body. In this posture arch the neck enough to the rear to place the forehead against the floor, thus creating a reverse cervical curvature (fig. 5.8). If that position is uncomfortable, you can start with the nose or chin against the floor. On an inhalation, slowly lift the forehead, brush the nose and chin against the floor, and lift the head, neck, and chest slowly, vertebra by vertebra. Lift mainly with the back and neck muscles, using the hands only as guides. As you extend the spine, try to create a lengthening feeling. You should be at ease; if you are straining you have come up too far. Try to remain in the posture, breathing evenly, for 10–20 seconds, and then come back down in reverse order, ending with the forehead against the floor. This is the classic beginning cobra (fig. 5.9). If you are a novice, you may do little more than raise your head, and it might appear as if this involves only the neck muscles. But even this slight movement will engage the deep back muscles from the head to the pelvis, and over time you will slowly develop the strength and flexibility to come up further.

To relax you can turn your head to one side and rest. If that is too stressful for your neck, you can place a large soft pillow under your chest and head, which permits your head to be twisted more moderately. Or another alternative is to twist a little more insistently and at the same time press the side of the head firmly against the floor with isometric contraction of the neck muscles, which will stimulate the Golgi tendon organs and cause reflex relaxation of the associated muscles. In any case, turn in the other direction after the next variation, and then alternate sides each time you do another.

Teachers often tell students to place their heels and toes together but to stay relaxed while coming up into the pose. That can be confusing because anyone who tries to do this will find that holding the heels and toes together in itself requires muscular activity. It is best to explain at the outset that the classic cobra should be done with no more than moderate tension in the lower extremities, and that the act of holding the heels and toes together serves this purpose. Students should also pay close attention to their breathing; they will notice that each inhalation lifts their upper body and creates more pull in their lower back and hips.

Figure 5.8. Classic cobra, starting position.

Figure 5.9. In the classic cobra posture, the upper extremities serve mainly as guides, and the head and shoulders are lifted using the deep back muscles as prime movers. The muscles of the hips and thighs then act as synergists for moderately bracing the pelvis.

THE COBRA WITH TIGHT LOWER EXTREMITIES

Now try a variation of the cobra with the lower extremities fixed solidly. With the chin against the floor, place the hands in the standard position. Then, keeping the feet together, tighten all the muscles from the hips to the ankles and lift up as high as you can with the back muscles, leading with the head and looking up. With the sacrum and pelvis stabilized by the tension in the lower extremities, you will be using only the erector spinae muscles to create the initial lift. As soon as you are up, each inhalation will lift the torso even more, and each exhalation will lower it down; both movements result from the action of the diaphragm. Inhale and exhale maximally if you are confused. The respiratory motion is more apparent here than with the classic cobra because the lower extremities are held more firmly in position. Except for the hand position, this posture is identical to the cobra variation we did in chapter 2 (fig. 2.10). There the movements of the upper body were discussed in terms of lifting the base of the rib cage in diaphragmatic breathing. The same thing happens here except that now we’re calling it a diaphragm-assisted backbend.

A RELAXED COBRA WITH MILD TRACTION IN THE BACK

If your lower back is tender the classic cobra will be uncomfortable, and the most natural way to protect and strengthen the region will be to tighten everything from the waist down as in the previous variation. But there is an alternative—you can push up mildly into the cobra with the arms in a modified crocodile position. Instead of using the deep back muscles to extend the spine, which pulls the vertebrae closer together and compresses the intervertebral disks, we’ll push up with the arms to lift the shoulders, place traction on the lumbar region, and remove tension on the intervertebral disks.

Start this posture with the hands on top of one another just underneath the forehead and with the elbows spraddled out to the side, or place the hands flat on the floor with the thumbs and index fingers making a diamond-shaped figure, the tips of the thumbs under the chin. Then, keeping the elbows, forearms, and hands planted against the floor, lift the head actively, push up with your arms, and create a gentle isometric pull with the arms as though you were wanting to pull yourself forward. At the same time observe that the leg, thigh, hip, and back muscles all remain relaxed. You are not going anywhere with the isometric lift and pull with the arms; you are only creating a mild traction in the back that encourages relaxation.

This exercise protects the lower back just as effectively as keeping the hips and thighs firm because the back and lower extremities automatically stay relaxed as you lift up. The oddity of protecting yourself with both mechanisms at the same time will be obvious if you come into the posture and then tighten muscles generally from the waist down.

Notice how this posture affects your breathing. The tension on the chest from the arms and shoulders keeps it immobilized, in contrast to the diaphragm-assisted lift in the classic cobra and the previous variation. Most of the respiratory movement is felt as abdominal breathing exactly as in the stretched crocodile posture (fig. 2.23): the lower back lifts with each inhalation as the dome of the diaphragm descends, and the lower back drops toward the floor with each exhalation as the dome of the diaphragm rises.

CREATING TRACTION WITH THE HANDS AND ARMS

For this variation start with the hands alongside the chest, the heels and toes together, and the chin rather than the forehead on the floor. Then, instead of creating traction with the elbows and forearms, create it by pressing the heels of the hands toward the feet isometrically. This is similar to creating traction by pulling from the elbows, but the action is more difficult to control. You started this posture with just enough tension in the lower extremities to hold the feet together. Now try to let that melt away. Also try to minimize your tendency to push the torso up with the hands, even though that is hard to avoid while you are creating tension for pulling forward. This is a demanding whole-body concentration exercise. Notice how your breathing differs from that in the previous variation. The chest is not restricted—the diaphragm both flares the chest wall from its lower border and lifts the upper body, creating diaphragmatic rather than abdominal breathing.

RAISING UP AND DOWN WITH BREATHING

For this variation, start with your chin on the floor, the hands in the standard position alongside the chest, the heels and toes together, and the hips squeezed together. Then inhale while lifting your head and shoulders, and exhale back down until your chin touches the floor, breathing at the rate of about four breaths every ten seconds. You can experiment with keeping the hips somewhat relaxed, but it is more natural to keep them firm so that inhalations lift you higher. This exercise differs from the classic cobra in that it involves constant movement. You come all the way up and all the way down using a combination of the diaphragm and the back muscles, while in the cobra you hold the position as much as possible with the back muscles alone and allow the diaphragm to bob you up and down from there. A nice variation on this exercise is to turn your head to one side or the other with each inhalation: inhale, up (right); exhale, down (center); inhale, up (left); exhale, down (center); and continuing with a natural cadence for 10–20 breaths. During each successive inhalation, twist more insistently, lift more insistently, and expand your inspiratory capacity as much as possible with empowered thoracic breathing. This is a powerful and yet natural and comfortable exercise.

THE DIAPHRAGMATIC REAR LIFT

The next several variations of the cobra depend on reviewing the diaphragmatic rear lift (fig. 2.11). Summarizing from chapter 2, come into the standard preparatory posture for the classic cobra except that now the chin instead of the forehead is against the floor. Relax the entire body, especially below the chest, and then breathe deeply while keeping the chest and chin against the floor. Provided the deep back muscles, hips, and thighs are all free of tension, inhalation will arch the back and lift the hips, and exhalation will allow the lumbar region to flatten and drop the hips back down. At first, breathe quickly, almost as in the bellows exercise, and then slow your respiration down to observe the finer changes in tension and movement. In chapter 2 this exercise illustrated the connections of the diaphragm. Here it illustrates how lifting the hips (instead of the base of the rib cage) with the diaphragm creates another variation of diaphragm-assisted backbending.

ANOTHER COBRA WITH RELAXED LOWER EXTREMITIES

This next variation involves doing the cobra with the lower extremities completely relaxed, which is a posture that will challenge the concentration of even advanced students. Start with your chin on the floor and let your feet fall slightly apart into the position in which you will be most relaxed (heels in and toes out, or vice versa). Then slowly lift the head and chest, monitoring muscles in the lower half of the body to make sure they do not contribute to the lifting effort. This is easy enough at first, but it starts to feel unnatural as you rise more fully into the posture. Come up as far as you can, hold, and then come down slowly. Keep checking to make sure you do not feel a wave of relaxation on your way down, indicating that you tensed up as you lifted into the posture.

It’s the gluteal muscles that are the most difficult to hold back in this pose. When you lift up into the cobra, you ordinarily support the effort of the deep back muscles by bracing the pelvis with the gluteus maximus muscles, and this insures that the erector spinae and other deep back muscles will lift only the upper part of the body. But if you relax from the waist down, the erector spinae muscles have two roles instead of one. They still lift the upper half of the body by way of their insertions on the chest, but now they also pull on the ilium and sacrum from above, deepening the lumbar lordosis and rotating the coccyx to the rear for an anterior pelvic tilt. If you have ever had back problems, this exercise will at once make you aware of your vulnerability, so do it only if you remain comfortable from start to finish.

Not surprisingly, the diaphragm contributes importantly to this posture; it acts in perfect cooperation with the erector spinae muscles by lifting both ends of the torso at the same time, thus assisting the backbend both from above and below. As we saw in chapter 2, this happens because the costal portion of the diaphragm lifts the rib cage and because the right and left crura lift the relaxed hips.

THE COBRA WITH REVERSE BREATHING

For an even more difficult concentration exercise, lie prone with your hands alongside your chest in the standard position, and come in and out of the cobra posture while reversing the natural coordination of diaphragmatic inhalations with the concentric shortening of the back muscles. Do this as follows: First, keep the chin on the floor while inhaling. Then exhale while tightening the hips and thighs (which holds them against the floor), and at the same time raise the head and shoulders. Next, inhale and relax the hips completely (which causes the hips to rise) as you lower the head and shoulders. Putting it differently: raise the head and chest during exhalation, and lower them during inhalation; tighten the hips and keep them down during exhalation, and relax them and permit them to rise freely during inhalation. This is disorienting until you master it. The exercise will work best if you take about one breath every four seconds.

After several exhalations up and inhalations down, try breathing more slowly. Relax completely during a deep but leisurely inhalation, and allow the crus of the diaphragm to deepen the lumbar lordosis from below. As exhalation begins, tighten the gluteals so the back muscles can lift the upper part of the body concentrically from a strong base without any help from the diaphragm. Then, during the next inhalation the chest will drop slowly to the floor, and the diaphragm will again lift the lower spine and hips as the back muscles and lower extremities relax. This is a difficult exercise, but after you have mastered it, along with the other variations of the cobra, you will have experienced all the possible combinations of breathing in relation to lifting up and down in the cobra. This posture helps place all the more natural possibilities in perspective. And apart from its value as a training tool, once you have succeeded in learning to do the sequence smoothly and rhythmically, the exercise is very soothing.

THE SUPPORTED INTERMEDIATE COBRA

Here is a good way to prepare for the advanced cobra. Lying prone with the chin on the floor, stretch the hands overhead with the arms and forearms parallel and the palms down. Keeping the elbows extended and the heels and big toes together, lift the head as high as possible, and pull one hand and then the other back toward the head in small increments. This will lift the upper half of the body. The back is passive; it is not doing the work of lifting you. One arm braces while the other pushes the body up, inch by inch. When you are up, find a relatively relaxed position with your weight resting on a combination of the hands, the lower border of the rib cage, and the pelvis. Or you can suspend the weight of your chest and abdomen between the hands and pelvis if that feels comfortable (fig. 5.10). Keeping the elbows extended is a feature of this posture alone. We’ll dispense with doing that when we come to the full expression of the advanced cobra.

Most beginners make two mistakes in this exercise. One is to hang passively between their arms. Don’t do that. Lift the chest and pull the scapulae down and laterally. With experience, you can find a position in which you are keeping the pelvis, or possibly the pelvis and the rib cage in combination, against the floor without hanging passively. The other common error is to let your attention stray from the forearm extensors, which permits the elbows to become slightly flexed.

Everyone will have a different limit to how far they can lift up and at the same time keep the pelvis on the floor. It will depend, obviously, on how much passive extension their lumbar spines can accommodate. Some will end up with their shoulders lifted up off the floor only a few inches; others may have enough flexibility to face the ceiling (fig. 5.11). If you are inflexible, notice that you feel vulnerable with the back muscles relaxed. Find a position in which you can feel some of that vulnerability and yet remain still without pain or anxiety. As in other variations of the cobra, take deep empowered thoracic inhalations.

Figure 5.10. Supported intermediate cobra. In this pose the hands are pulled back incrementally (always keeping the elbows extended) until the pelvis is almost lifted off the floor. The head is pulled backward and the scapulae are pulled down and laterally (see chapter 8 for details of scapular movements), being careful not to hang the chest passively between the shoulders.

As soon as you are accustomed to the relaxed posture, pull the head back further and engage the back muscles isometrically. Now the inner feeling of the posture changes. The engaged back muscles make it feel safer even though your position has not shifted. Then, as soon as you have accommodated to this new feeling, bend the knees carefully, drawing the heels toward the head while keeping the elbows fully extended. Don’t hurt your knees. This is an unusual position for them. It is fairly safe for the back because you have engaged the erector spinae muscles, but lifting the feet increases the intensity of the posture, so be watchful. You also have to concentrate on keeping the elbows straight because neurologic interconnections between motor neurons for flexors and extensors are such that the act of flexing the knees reflexly inhibits the motor neurons that innervate the extensors of the forearm (chapter 1), especially if the movement causes the slightest pain in the back or knee joints. Hold the posture for 10–20 seconds if you can do so confidently. Then slowly lower the feet back to the floor and slide the hands forward to the beginning position.

If you are not very flexible the lumbar region is bent to its maximum, especially when the feet are raised, and you will notice that breathing does not create marked external effects on the posture. Inhalation increases (and exhalation decreases) internal tension, but we do not see much accentuation or flattening of the lumbar region. In company with this, it may feel appropriate to breathe cautiously if you are at your limit. And even if you are flexible and comfortable, breathing deeply in this posture is not easy because the rib cage is constrained by the arm position. Nevertheless, if you would like to expand your inspiratory capacity (chapter 2), inhale thoracically as much as the posture permits.

Figure 5.11. Supported cobra facing the ceiling. Flexible students can bend their spines enough (about 70° in this case) to face the ceiling and yet keep their thighs on the floor.

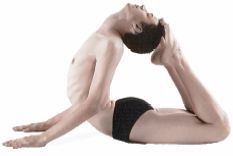

THE ADVANCED COBRA

To do the advanced cobra, start from the same beginning position as the classic cobra, with the forehead on the floor and the fingertips in line with the nipples. Next, brush your nose and chin along the floor and slowly start lifting the head and chest with the back muscles. Then, keeping the back muscles engaged, slowly start to straighten the elbows until you have extended the back and neck to their limits. The extent to which the elbows are straightened will be a reflection of how much the spine is extended, as well as a reflection of the lengths of the arms and forearms. Beginners will not be able to come up very far, and it will be rare for even advanced students to straighten their elbows completely. It’s not necessary anyway. The idea of this posture is to keep everything active. The deep back muscles, specifically, should be monitored constantly to make sure they are supporting the lift and not relaxing as the forearms extensors start contributing to the posture.

Keeping the back muscles active sounds like it ought to be easy, but for those whose spines are inflexible these muscles will be working against the antagonistic actions of the iliacus and psoas muscles, which maintain the first line of protection for restricting the bend, as well as the abdominal muscles, which stay tight to maintain the intra-abdominal pressure that is so important for minimizing strain on the intervertebral disks. It is a natural temptation to simply relax and support the posture entirely with the upper extremities. Don’t do it. That’s more like the next posture, the upward-facing dog.

As you progress in your practice of the advanced cobra, you will gradually become confident and flexible enough to allow the iliopsoas muscles and the abdominal muscles to lengthen eccentrically and even relax without releasing tension in the back muscles, and when that happens the back muscles will contribute to extension more effectively. The last step, after acclimating to the posture in its essential form, is to draw the feet toward the head (fig. 5.12).

Figure 5.12. In the advanced cobra, highly flexible students can bend their lumbar spines 90° and touch their feet to their head. For most students spinal and hip inflexibility (along with resistant hip flexors and abdominal muscles) limit coming fully into this pose.

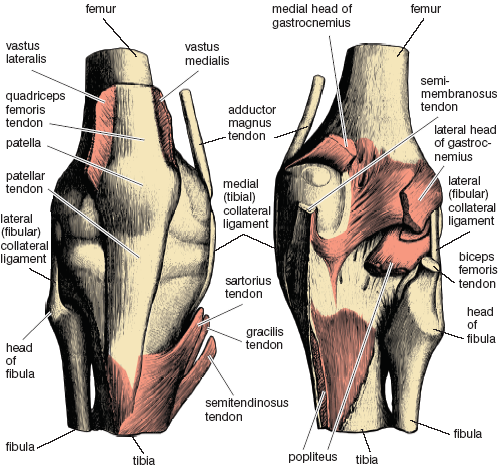

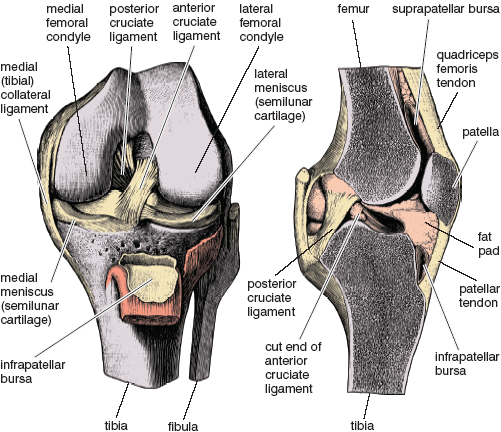

As with the supported intermediate cobra, it is most important to keep the chest lifted and the shoulders pulled down and back. Nothing will violate this posture as certainly as allowing the chest to hang passively between the arms. And if you take the option of bending the knees and pulling the feet toward the head, be careful of stressing the ligaments that surround the knee joint.

Breathing issues in the advanced cobra are similar to those for the supported posture. The diaphragm will contribute to keeping the pose stable and restrict the bend for those who are less flexible, and it will deepen the backbend for those who find themselves flexible enough to come convincingly into the posture. In general, the advanced pose will not be very rewarding for anyone who is not flexible enough to sense that the diaphragm is either deepening the bend or creating tension for doing so, as well as getting out of the way of empowered thoracic breathing.

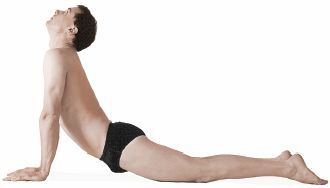

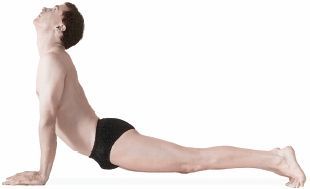

THE UPWARD-FACING DOG POSTURES

The upward-facing dog is not a cobra posture, but it begins in the same way and then goes one or two steps beyond. It is like a suspension bridge. The arms and forearms support the posture from above, the knees or feet support it from below, and the chest, abdomen, pelvis, and thighs are suspended between. Four variations are presented here, and in each one you support your weight differently.

To prepare for the upward-facing dog, start with the chin on the floor, the hands alongside the chest a little lower than for the cobra, the feet together, and the toes extended. Slowly lift the head and then the shoulders, keeping the muscles of the lower extremities engaged. As soon as you reach your limit of lifting with the back muscles, extend the elbows slowly, lifting your body even higher until your weight is supported by the arms, knees, and the tops of the feet. It is important to do this without relaxing the back muscles (fig. 5.13). The pose should be active front and back. Those who are especially flexible will have to keep the abdominal muscles engaged to avoid dropping the pelvis to the floor; those who are not flexible will not have this difficulty because their abdominal muscles are already tense. As in the advanced cobra, lift the head, neck, and chest. Don’t allow the chest to hang passively between the shoulders. Come down in reverse order, taking a long time to merge the releasing of forearm extension into supporting the posture entirely with the deep back muscles.

Now try the same exercise with the toes flexed instead of extended. Keeping your knees on the floor and supporting yourself on the balls of the feet at the same time makes this a tighter posture because now the gastrocnemius muscles in the back of the calf are stretched. This places additional tension on the quadriceps femoris muscles, which (among their other roles) are antagonists to the gastrocnemius muscles; the tension in the quadriceps femoris is in turn translated to the front of the pelvis by way of the rectus femoris. The tension from the rectus femoris then restricts how far the pelvis can drop toward the floor. It’s easy to prove. If you go back and forth between the two postures you’ll feel immediately how the two alternative toe positions affect the pelvis—toes flexed and curled under, the pelvis is lifted; toes extended back, the pelvis drops.

In the full upward-facing dog, the knees are extended and you are supporting yourself between the hands and feet instead of between the hands and knees. This is a whole-body commitment requiring a lot more muscular tension in the quadriceps femoris muscles than the simpler posture. You can support your weight on your feet either with the toes flexed (fig. 5.14) or with the toes extended to the rear. Try both positions. Neither one is stressful if your feet are comfortable.

Breathing mechanics in the upward-facing dog are different from any other posture because the body is suspended in mid-air. You can easily rock back and forth or move from side to side like a suspension bridge in the wind, and this freedom of movement allows for deep thoracic inhalations and yet permits the diaphragm to deepen the backbend even in students who are not very flexible.

THE OPEN-AIR COBRA

This exercise requires good strength and athletic ability, healthy knees, and a prop made up of two cushioned planks; one (cushioned on top) is several feet off the floor, and another (cushioned on its underneath side) is slightly higher and situated to the rear of the first. The front plank will support the body at the level of the mid-thighs, and the rear plank will prevent the knees from flexing and the feet from flying up. Such a contraption is often found in health clubs. You will climb into the apparatus and lie in a prone position. The thighs will be supported from below by the front plank and the calves will be anchored in place from above by the rear plank. First, you allow the torso to hang down, flexed forward from the hips. From this position, you straighten the body and raise your head and shoulders as high as you can. The body from the thighs up will be suspended in mid-air as soon as you lift away from the floor.

This exercise is an excellent example of the manner in which gravity operates in relation to muscular activity. Little effort is required to initiate the movement for swinging the torso up the first 45°. Then, as the body comes toward the horizontal position you start getting more exercise. This feels similar to the classic cobra posture, except that it is more difficult because you are lifting the body from the fulcrum of the thighs instead of the pelvis. Then, as you arch up from that site you can begin to look right and left like a real cobra appraising its environment. Coming yet higher, the iliopsoas and abdominal muscles finally become the main line of resistance to the concentric activity of the back and neck muscles.

COBRAS FOR THOSE WITH RESTRICTED MOBILITY

The vertebral columns in older people sometimes become bent forward structurally, reverting to the fetal state of a single posterior curvature. The main problems with this, apart from not being able to stand up straight, are that the intervertebral disks have lost their fluidity, the joint capsules have become restricted, extraneous and movement-restricting deposits of bone have accumulated near joints, and muscles have become rigid. Those who have this condition are rarely able to lie comfortably on the floor in a prone position. But if they lie on cushions that support the body in a slightly flexed position and if the height of the cushions is adjusted carefully, all the simple variations of the cobra are feasible and will have beneficial effects throughout the body.

Figure 5.13. Upward-facing dog with knees down and toes extended. Come into this first of four dog postures systematically, and never hang between relaxed shoulders.

Figure 5.14. Upward-facing dog with knees up and toes flexed. Whole-body tension is required except in those who are so inflexible that their body structure keeps their thighs off the floor. The pose is like a suspension bridge.

ASHWINI MUDRA AND MULA BANDHA IN THE COBRAS

Ashwini mudra (chapter 3) is more natural in the upward-facing dog than in any other hatha yoga posture. The urogenital triangle is exposed, the genitals are isolated from the floor, the muscles of the urogenital triangle are relaxed, the gluteal muscles are engaged, and the pelvic diaphragm is automatically pulled in. Mula bandha (chapter 3), on the other hand, is natural in all of the postures in which the pelvis is resting against the floor, which means all the postures just covered with the exception of the upward-facing dog. Anyone who is confused about distinguishing between ashwini mudra and mula bandha can go back and forth between the upward-facing dog and an easy-does-it version of the classic cobra (in this case with the heels and toes together but with the gluteal muscles relaxed), and their confusion will vanish.

The locust posture is named for the manner in which grasshoppers (locusts) move their rear ends up and down. The locust postures complement the cobras, lifting the lower part of the body rather than the upper, but they are more difficult because it is less natural and more strenuous to lift the lower extremities from a prone position than it is to lift the head and shoulders.

We can test the relative difficulty of one of the locust postures with a simple experiment. Lie prone with the chin on the floor and the backs of the relaxed hands against the floor alongside the thighs. To imitate the cobra, lift the head and shoulders. Look around. Breathe. Enjoy. This exploratory gesture could hardly be more natural. Notice that it doesn’t take much effort to lift up, that it is easy to breathe evenly, that the upper extremities are not involved, and that the movement doesn’t threaten the lower back. By contrast, to imitate the locust we’ll need three times as many directions and cautions. Starting in the same position, point the toes, extend the knees by tightening the quadriceps femoris muscles, and exhale. Keeping the pelvis braced, lift the thighs without bending the knees. Don’t hold your breath, and be careful not to strain the lower back. What a difference! While almost anyone new to hatha yoga can do the first exercise with aplomb, the second is so difficult and unfamiliar that new students have to be guided from beginning to end.

THE HALF LOCUST

The easiest locust posture involves lifting only one thigh at a time instead of both of them simultaneously. This is only about a tenth rather than half as hard as the full locust because one extremity stabilizes the pelvis while the other one is lifted, and this has the effect of eliminating most of the tension in the lower back. To begin, lie prone with the chin on the floor, the arms alongside the chest, the elbows fully extended, and the backs of the fists against the floor near the thighs. Point the toes of one foot, extend the knee, and lift the thigh as high as possible, but do this without strongly pressing the opposite thigh against the floor (fig. 5.15). Breathe evenly for ten seconds, come down slowly, and repeat on the other side.

The half locust is a good road map for the full posture because we see similar patterns of muscular activity, but it is easier to isolate and analyze the various sensations when one thigh is braced against the floor. To create the lift, the gluteus maximus and the hamstring muscles hyperextend the thigh against the resistance of the abdominal muscles, the iliopsoas muscle, and the quadriceps femoris. The hamstring muscles don’t insert directly on the thigh. They insert on the back of the tibia, but in this case they act only on the pelvis because their tendency to flex the leg at the knee joint is prevented by strong isometric contraction of the quadriceps femoris muscle, which keeps the knee joint extended. It is as if you have attached a rope to the most distant of two boards that are hinged end-to-end; the far board is the tibia, and the near board is the femur. You want to lift the two boards as a unit to keep them aligned, but the rope goes only to the distant board. So another set of supporting lines has to run on the front (locking) side of the hinge to prevent the boards from folding up. The hamstring muscles are the ropes; the quadriceps femoris muscles are the supporting lines.

The half locust posture is worth more attention than it usually gets. In a slightly different form it is commonly prescribed by physiatrists and physical therapists for the recovery period that follows acute lower back pain. If you are on the mend from such a condition, and if you are able to lie in the prone position without pain, you can rapidly alternate what might be called thigh lifts—extending the knees and raising them (one at a time) an inch off the floor at the rate of about four lifts per second. If you repeat the exercise twenty to thirty times several times a day, it will strengthen the back muscles from a position that does not strain the lower back.

Figure 5.15. Half locust. This posture, which should be done without pressing the upper extremities and the opposite thigh strongly against the floor, is excellent for leisurely analysis of complex muscular and joint actions.

THE SUPPORTED HALF LOCUST

A more athletic posture supports the lifted thigh with the opposite leg and foot. Lie in the same prone position with the chin on the floor. Place the right fist alongside the right thigh, with the back side of the hand against the floor, and place the left hand, palm down, near the chest. Twist your head to the left and bend the right knee, flexing the right leg 90°. Then, using an any-which-way-you-can attitude—in other words, the easiest way possible—swing the left thigh up and support it on the right foot just above the left knee. Nearly everyone will have to lift their pelvis off the floor to get the left thigh high enough, and that is the purpose of twisting the head to the left and of having the left hand near the chest to help you balance. Try not to end up with the entire body angled too far off to the right, however. Use your breath naturally to support coming into the posture, taking a sharp inhalation on the lift, and then breathing cautiously but evenly while the foot is supporting the thigh. Even though you came into the posture with a swinging movement, try to come down slowly by sliding the right foot down the left leg. Repeat on the other side.

You can refine this exercise to make it both more difficult and more elegant if you come up slowly instead of with a swinging movement. Concentrate on breathing evenly throughout the effort and on keeping the pelvis square with the floor. Settle into the posture by slowly relaxing the abdominal muscles and hip flexors, which increases extension of the back. Finally, if you are flexible enough, deepen the backbend with your breathing, supporting the full posture both with the diaphragm and with deep thoracic inhalations (fig. 5.16).

THE SIMPLE FULL LOCUST

As soon as your are comfortable with the half locust you can begin to practice the full locust. The basic posture, which we’ll call the simple full locust, is a difficult pose, but we place it first to give an idea of the posture in its pure form. The last three variations form a logical sequence which we’ll call the beginning, intermediate, and advanced locusts.

To do the simple full locust, place the chin on the floor, the arms alongside the thighs, the forearms pronated, and the backs of the fists against the floor. If you want to make the posture more difficult, supinate the forearms and face the backs of the fists up. In either case point the toes to the rear, tighten the gluteal muscles, and last, keeping the knees extended, hyperextend both thighs, allowing them to become comfortably abducted at the same time. Do not try to aid the effort for hyperextension of the thighs with the arms at this stage. That will come later. If you are a beginner you may not have enough strength to make any external movement at all, or you may barely be able to take some of the weight off the thighs, but you will feel the effects in the lumbar, lumbosacral, sacroiliac, and hip joints, and you will still benefit from the effort.

When you raise the thighs in the simple full locust, you are trying to hyperextend them with the gluteus maximus muscles acting as prime movers, and doing this with both thighs at the same time makes this posture a great deal more difficult than the half locust: you are lifting twice as much weight, the pelvis is reacting to the muscular tension instead of stabilizing the posture for lifting just one side, and the lumbar lordosis is accentuated in one of the most unnatural positions imaginable. To make this seem a little easier you can take the option of allowing the knees to bend slightly, which will have two effects: it will permit the hamstring muscles to be more effective in aiding extension of the thighs, and it will facilitate their roles as antagonists to the quadriceps femoris muscles. The reason for allowing the thighs to become abducted brings us back to the hips; the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus (figs. 3.8b, 3.10a–b, 8.9, 8.12, and 8.14) are abductors, and holding the thighs adducted keeps these muscles in a stretched position and generally impedes hip hyperextension. The simple full locust is a challenging posture if your measure of success is external movement, but if you practice it daily you will soon be able to lift up more convincingly.

THE BEGINNER’S FULL LOCUST

The next variation, the beginner’s full locust, is the easiest in the series. Keeping the elbows straight, place the fists under the thighs, pronating the forearms so that the backs of the fists are against the floor, and pull the arms and forearms under the chest and abdomen. Again, keeping the heels, toes, and knees together, try to lift the thighs while holding the knees fairly straight (fig. 5.17). This variation will affect a higher position in the lumbar region than the first posture, and your attention will be drawn to the genitals rather than the anus, favoring activation of mula bandha over ashwini mudra.

Figure 5.16. Supported half locust. Beginning students can learn this posture by first turning the head in the same direction as the thigh that will be raised, then swinging the thigh up and catching it with the opposite foot; refinements to provide for more grace and elegance can come later.

The beginner’s full locust is easier than the simple version because the fists provide a fulcrum that allows you to lift the thighs into extension from a partially flexed position. In the simple version of the full locust in which you are trying to lift your thighs from an extended to a hyperextended position, most of your effort goes into the isometric effort of pressing the pelvis more firmly against the floor. For unathletic beginners this is the end of the posture. But they should still experience both—the simple full locust to feel the essence of the basic pose, and the beginner’s full locust to feel a sense of accomplishment.

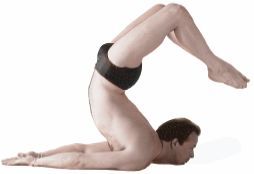

THE INTERMEDIATE FULL LOCUST

You need to develop more strength in your shoulders, arms, and forearms for the intermediate variation of the locust. It is exactly like the previous posture except that you use the arms, forearms, and interlocked hands to press against the floor, and this helps you lift up much further. It requires a whole-body effort involving all the muscles on the anterior sides of the arms and shoulders, plus the deep back muscles, the gluteal muscles, and the hamstrings. The intensity of the commitment needed to raise the knees just a few inches off the floor is likely to surprise even a good athlete. But lift as high as possible and hold (fig. 5.18). Many benefits are gained just by increasing the isometric tension in your personal end position.

Even though this posture requires a whole-body effort, you feel it most significantly in the lower back. You can check this in someone else by placing your hands on either side of their vertebral column as they initiate the lift. In everyone, you will feel the muscles in the lower half of the back bulge strongly to the rear, and in those who are able to lift their knees six inches or more off the floor, you will notice the bulge spreading throughout the back as more and more of the erector spinae is recruited into the effort.

Figure 5.17. This beginner’s full locust is easier than the simple full locust (not illustrated) because the position of the fists under the upper portions of the thighs permits them to act as a fulcrum for lifting the thighs. This posture also favors holding mula bandha over ashwini mudra (which is more in character for the simple full locust).

One of several unique characteristics of the locust posture is the extent to which the pelvis is braced. All of your efforts to lift are countered by numerous muscles acting as antagonists from the anterior side of the body: the rectus femoris pulls on the anterior inferior spine of the ilium; the psoas pulls on the lumbar spine; and the iliacus pulls on the pelvis. All of these muscles and their synergists act together from underneath to brace the body between the knees and the lumbar spine. And with this foundation stabilized, the gluteus maximus muscles, hamstrings, and erector spinae operate together to lift the pelvis and lower spine as a unit. The gluteus maximus muscles will first shorten concentrically and then act isometrically to place tension on the iliotibial tracts, which run between the ilia and the proximal portions of the tibias and fibulas (figs. 3.8–9 and 8.12). The actions of the gluteus maximus muscles are supported synergistically by the hamstrings, which, like the gluteus maximi, pull between the pelvis (in this case the ischial tuberosities) and the legs.

By themselves the gluteus maximus muscles and their synergists would not take you far, as in the case of the simple and beginner’s full locust, but when the arms and forearms are strong enough to help drive you up, the muscles on the back side of the body are able to act more efficiently. This is a powerful posture but one of the most unnatural postures in hatha yoga, and since much of the tension for raising the thighs is brought to bear on the lower back, it is for intermediate and advanced students only.

The whole-body muscular efforts needed to maintain the intermediate full locust are intense, and since the abdominal muscles and the respiratory and pelvic diaphragms have to support the effort from beginning to end, inhalations will not be very deep, and the externally visible effects of breathing will be negligible.

Figure 5.18. This intermediate full locust is manageable only by intermediate and advanced students; those who are not both strong and flexible will not be able to lift this far off the floor. In any case, what differentiates the posture from the beginner’s full locust is the way the pose is supported using the upper extremities.

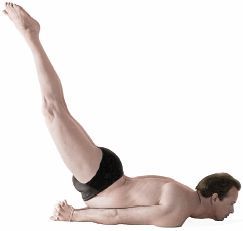

ADVANCED FULL LOCUST

The advanced full locust is one of the most demanding postures in hatha yoga. To do it, those who are able to lift themselves up moderately in the intermediate practice now roll all the way up in one dynamic movement, balancing their weight overhead so the posture can be maintained without much muscular effort. This is only for athletes who are confident of their strength, flexibility, and the soundness of their spines. Those who can do it always seem to be at a loss for words when they try to explain what they do—speaking vaguely about concentration, breath, flexibility, and intention. It’s a whole-body effort. If any link is weak the posture cannot be done.

To press up into this posture, nearly everyone has to lock the elbows and then interlock the hands underneath the body in some way. You can interlock the little fingers and keep the rest of the fingers and palms against the floor. Or you can clasp the fingers together as in fig. 5.18, starting the position with the hands cupped around the genitals. In either case, lift up into the intermediate position using the arms and back muscles. And then, without hesitating, inhale, bend the knees, press the arms and forearms against floor more forcefully, and in one fluid movement lift into the final posture with the feet straight up. Ideally, this is a balancing position. Once you are in it you will need to keep only moderate isometric tension in the back muscles, you will not have to keep pressing so vigorously with the arms, and you can flatten the backs of the hands against the floor. Flexibility for backbending really pays off here, the more the better, and the easier it will be to balance without holding a lot of tension in the deep back muscles. You can either keep your feet pointing straight up or lower them toward the head (fig. 5.19), which makes it even easier to balance.

Breathing is one of the most important elements of the advanced locust, and most students will find it necessary to take a deep inhalation to assist the action of coming up into the pose. After that there are two schools of thought. One is to exhale as you come up and keep the airway open according to the general rule for hatha yoga postures. This is the best approach because the pose is executed and supported by a combination of the upper extremities, the deep back muscles, and intra-abdominal pressure—not by intrathoracic pressure (chapter 3). But if you can’t quite do that you can close the glottis to lift up and then breathe freely once you are balanced.

If you do not have enough flexibility in the back and neck to remain comfortably balanced after you are in the posture, you can place the palms flat against the floor, bend the elbows slightly, and support the lower part of the chest (and thus the whole body) with the arms and elbows. This will enable you to build up time in the pose.

The advanced locust places the neck in more extreme, and forced, hyperextension than any other posture, and to prepare for this students will find it desirable not only to work with backbending postures in general, but also with special postures that extend the neck to its maximum. The cobra postures (figs. 5.9–12), the upward-facing dogs (figs. 5.13–14), and the scorpion (fig. 8.31b) are all excellent for this purpose.

Although the advanced locust has to be treated as a dynamic whole, try to do it slowly. Many students have been hurt by falling out of the posture when they have tried to toss themselves up into the full pose before they have developed sufficient strength and control. If you are almost able to do the advanced locust, you will soon be able to master it by developing just a little more lumbar flexibility in combination with more strength in the arms and back.

The prone boats curve up at each end like gondolas, lifting both ends of the body at the same time, and in this manner they combine elements of both the cobra and the locust. We discussed a simple prone boat in chapter 1 to illustrate movements of the body in a gravitational field. And since these postures work against the pull of gravity as well as against muscular and connective tissue restraints, they can be difficult and discouraging to many beginning students, who often cannot even begin to lift up into them. To add insult to injury, instructors may tell students to come up into the postures and relax! We’ll remedy this by starting with an easy version. After a few weeks of regular practice, all of them become easy.

In the first version of the prone boat, lie with your chin against the floor, the heels and toes together, the arms along the sides of the body, and the back of the hands against the floor. Point the toes to the rear, tighten the quadriceps femoris muscles to extend the knee joints, and simultaneously lift the head, neck, chest, shoulders, thighs, and hips (fig. 5.20). If you have plenty of strength, lift the hands as well (fig. 1.15). Breathe evenly, and notice how the respiratory diaphragm lifts both the chest and the lower extremities with each inhalation and lowers them down slightly with each exhalation.

Figure 5.19. The advanced full locust is easier in certain respects than the intermediate version because here one is balancing rather than supporting the pose with muscular effort. No one should try this posture, however, who is not confident in their athletic prowess and 90° flexibility for backbending.

In the second version, which is a little harder than the first, again lie with your chin against the floor, with the heels and toes still together, but now stretch the arms out perpendicular to the body, palms down. Make blades of the hands, stretch the fingers, point the toes, extend the knees, and simultaneously lift all four extremities.

The third and most difficult version of the boat (fig. 5.21) is the same as the second except that the hands are stretched overhead with the elbows extended. Beginners usually resist this if you ask them to do it first, but if you start by leading them through the first and second versions they may be surprised to find that they have generated enough energy and enthusiasm to try the third. And rather than telling students to relax in the posture, instructors can suggest that they imagine they are lengthening the body in addition to lifting at both ends. This somehow enables them to raise up more efficiently and to feel more at ease.

Figure 5.20. In this easiest version of the prone boat (with oars coasting in the water), muscles are held firm on the back side of the body. Superimposed on that effort, the respiratory diaphragm lifts both the upper body and the lower extremities concentrically during each inhalation and drops them eccentrically during each exhalation, making this is a whole-body, diaphragm-assisted backward bend.

Figure 5.21. This third version of the prone boat is the most difficult one, and few students will be able to lift up this far, but if students start with the first two versions as preparatory poses, this one becomes easier.

As with the cobra postures, many older people who are chronically bent forward can benefit from a propped-up prone boat by placing supporting cushions under the torso. If the cushions are chosen and adjusted perfectly, their heads, arms, and feet will be in a comfortable beginning position. They can then lift up at both ends and be rewarded with a beneficial exercise.

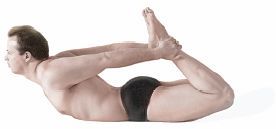

When an advanced student has come into the bow posture, it resembles a drawn bow: the torso and thighs are the bow, and the taut upper extremities and the legs are the string, which is drawn toward the ceiling at the junction of the hands and the ankles. The beginner’s posture is not so elegant. Most of its length is flattened down against the floor, and the pose is acutely hinged at the knee joints.

THE BEGINNER’S BOW

To begin, lie prone, flex the knees, and grasp the ankles. Try to lift yourself into a bow, not by backbending with the deep back muscles, which remain relaxed in the beginning posture, but by attempting to extend the legs at the knee joints with the quadriceps femoris muscles. An attempt to straighten the knee joints is little more than an attempt, since you are holding onto the ankles, but it does lift the thighs and extend the knees moderately (fig. 5.22).

It seems extraordinary that the quadriceps femoris muscles (figs. 3.9, 8.8, and 8.11) are the foremost actors for creating this posture, but that is the case. At first they are in a state of mild stretch because the knees are flexed. Then, shortening these muscles concentrically against the resistance of the arms and forearms creates tension that begins to pull the body into an arc. The quadriceps muscles are performing three roles simultaneously: extending the knee joints from a flexed position, lifting the thighs, and creating tension that draws the bow. The tensions on the knee joints can be daunting for a beginner, and many students do well just to grab their ankles. If that is the case, they may not lift up at all but merely contract the quadriceps muscles isometrically. That’s fine. Just doing this every day will gradually strengthen the muscles and toughen the connective tissue capsules of the knee joints enough to eventually permit coming up further into the posture.

THE INTERMEDIATE AND ADVANCED BOWS

Intermediate students will approach the bow with a different emphasis. They may use the quadriceps femoris muscles to lift the knees in the beginning, but they aid this movement by engaging the deep back muscles (the erector spinae) to create an internal arch. Then, as they come higher they will use the gluteal muscles in the hips to provide even more lift. And as the gluteus maximus muscles shorten concentrically for extending the hips, they lift the pelvis away from the floor and indirectly aid extension of the knee joint.

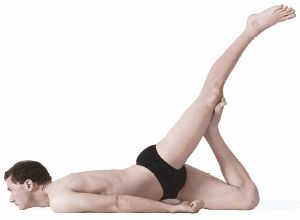

As advanced students lift into the posture, the lumbar region becomes fully extended and the hips become hyperextended. Such students will be dividing their attention among at least five tasks after they bend their knees and grasp their ankles: paying attention to stretch and tension of the quadriceps; maintaining a strong connection between the ankles and shoulders; watching the knee joints, which are receiving an unconventional stress; overseeing the complex muscular interactions between the quadriceps femoris muscles on one hand and the gluteal muscles that lift the thighs during extension of the hip joints on the other; and breathing, which is rocking the upper half of the body up with each inhalation and dropping it forward with each exhalation (fig. 5.23). Once these conditions are established, advanced students can take the final option of drawing the feet toward the head.

The nervous system orchestrates all of this complex musculoskeletal activity. In beginners, the quadriceps femoris muscles, deep back muscles, and gluteals do not receive clear messages to lift strongly into the posture. Instead, they are inhibited by numerous pain pathways that take origin from the joints (especially the knees), and from the front side of the body generally. Such reflex input should not be overridden by the power of will. Even advanced students who are able to lift up more strongly may find that discomfort in the sacroiliac, hip, and knee joints limits the posture. Experts honor these signals mindfully. Then, as soon as there is no longer any hint of pain, the only limitations to the posture are muscle strength and connective tissue constraints. Advanced students, having practiced the bow thousands of times over a period of years, know exactly how much tension can be placed safely on each joint and how to come down from the posture without harm.

Figure 5.22. In this beginner’s version of the bow posture, the main concentration is on lifting the body using the quadriceps femoris muscles (knee extensors on the front of the thighs).