1900. The Tenderloin. 241 West 41st Street

It was two a.m. The August heat was brutal and no one could sleep. Heads peered from the windows of rented rooms, drowsy and irritable; the desperate lay on makeshift beds; tick mattresses and folded sheets were spread on fire escapes and rooftops. Bodies scantily clad in undershirts and nightgowns rested in public view. The temperature hovered near one hundred degrees, driving decent and hardworking folks into the company of whores, thugs, policy runners, and gamblers: the folks who owned the street after midnight. Mothers with their children camped out on front stoops, small groups of men clustered at the corners, those with an extra nickel or dime to spare elbowed their way into crowded saloons for a pitcher of cold beer. On a night like this, all conspired to escape the suffocation of tenement flats, airless back bedrooms and sweltering buildings, to flee the assault of rank bodies, crying babies, embattled couples, and to shake off the general misery.

May Enoch couldn’t sleep either. The rented room on the top floor of Annie Jones’s house was unbearable. With each flight of stairs the temperature inched toward boiling, so the upper rooms were like hell. The heat ascended from the apartments below, and the sun beating the tar roof nearly baked them alive. It was too hot to prepare a meal, so she and Kid decided to go out for a bite to eat. They were on their way to Dobbins’s restaurant, but first he needed a cigar. He probably expected her to pay for that too. “Get the money from my woman” was a phrase that passed from his lips more frequently now that they were in New York. He didn’t ask her for any money but disappeared into McBride’s saloon to buy a cigar.

At the bar with his friends and a cold drink in his hands, Kid lost track of time, while May waited outside on the corner, trying not to sweat up her dress. He smoked a cigar, drank a glass of ginger ale with his friends Kid Black, Sam Palmetto, and George Bartell, and lounged at the bar. The man loved to kill time. May didn’t go inside McBride’s, but, impatient, hollered from the door, “Kid, come on up home,” and then waited. She had been waiting for nearly an hour, not just for him, but for something she couldn’t name that made her heart race whenever she turned phrases like I want and if only. What must she have looked like waiting for a man on the corner in all this heat? Like a fool? Like a beached whale? Like a woman on no one’s clock but her own? The folks walking across Forty-First Street or moving up Eighth Avenue trudged slowly, as if their legs were too heavy to lift. They moved indifferently, weighing whether to surrender to the lethargy, or anticipating something or someone to urge them on. It was too hot to move. Damn Kid. She was tired.

To wait idly on the corner for her man, to stroll the wide avenues of the city, to straddle Kid in a rented room on the top floor of a Tenderloin boarding house, to love and to hurt, as the black eye evidenced—defined the choreography of her life as much as scrubbing and cleaning and serving. The coital embrace of a young couple in a tenement bedroom, which was their own by the week and costing twice what white city dwellers were required to pay, was as sweet as freedom would get. She was from Philadelphia and he was from Virginia; they met in New Jersey, and expected the world from New York. What they found was a small perch in the Negro quarter. She lingered on the corner of Forty-First Street, unaware that by tomorrow she would long desperately for this, the liberty to waste time lost in her thoughts. She would remember this night vividly.

It was only their second week in New York, so she didn’t yet know what the city would hold. Did it have anything to offer her, something better than Philly, or Newark, or D.C., or just the same but at a price more dear? En route, she had left behind one man, a proper husband, after four years of marriage. She wondered what John Enoch was up to these days. Was he dead? Had he remarried too? Luckily there had not been a child. Had there been a child, she might not have left home or met Kid or ever moved to New York. Had there been a child, would she have dared to leave anyway? It was hard to pull up stakes and run with a baby. A child might have sealed her fate.

Next month, the fourth of September, would be their first anniversary. Things with Kid had been good enough for them to try their luck in New York. If there was luck to be found anywhere for a Negro, it was here. New York was the largest black city in the north. It was more alive, more dangerous than Philadelphia. This was an auspicious year and she, like every other Negro, hoped 1900 was a portent of change. Yes indeed, New York was the city for a new life and a new century. Black folks yearned desperately for a break with the past, a rupture with the dark days, so they fashioned themselves New Negroes and spoke tirelessly of regeneration and awakening in the hope that the world might follow their lead and yield a better set of arrangements.

The hand was tight on her left arm, before she turned and saw his face. He was pulling her up the street before she could utter a word. What the hell was this white man doing? People were watching but no one did anything, said anything. A colored woman could be grabbed in the street and no one said a damn word or uttered a peep. No matter where you went there was always some white man you had to tell to get his hands off you. When you least expected it, when you were lost in reverie about the good life in the city, these hands suddenly appeared, as if always waiting to snatch you; the moment you let your guard down, they did exactly that. What are you doing? He kept on pulling her. Being new to the neighborhood, May didn’t recognize him, she didn’t know that he made it a regular practice to stand on the corner and “abuse black men and women at will.” He was a terror and he took pride in being every Negro’s nightmare. Colored folks hated him, but he didn’t care. It stoked his appetite for violence; the fear and the hate inspired him. So when he dragged May up the block, Thorpe didn’t say a word. Often the threat was enough to force them to their knees, others times they had to be rough-handled to yield. No matter how they pleaded, no matter what they had been forced to do, he booked them without fail. (The corruption and harassment in the Tenderloin was legend. Graft, bribery, and extortion transformed the police into wealthy men. The great yield—the most succulent part of the loin—had bestowed the area with its name.)

When Kid exited from the side door of McBride’s, he saw a white man with his hands on May, pushing and pulling at her. He ran up the block after them. “Hey, let go of my woman.” In court, when he recounted everything that had happened, he spoke in the standard, the way white folks did, proving he wasn’t some ignorant nigger. On the stand, he would say, “What is the trouble? Why are you abusing her?”

“It is none of your damn business. Don’t you like it?” said Thorpe.

“Hell no.”

Kid ordered May to get the hell out of there and she did. Then the white man grabbed his collar. The first blows landed on Kid’s face and head, toppling him onto the sidewalk. He was sprawled in the street, and the white man pummeled him with a club, taunting him, daring him to rise. “Get up, you black son of a bitch.” Kid reached for the penknife in his pocket. He jabbed two or three times, and then the white man fell into the gutter. Blood covered the front of his shirt, slick and glistening. Kid stood there, frozen, glaring at the white man moaning and cursing in the street. Then he fled.

A white man smoking in the alley next to the theater saw a light-skinned colored woman with a black eye rush up the street. He was the one who told the police where they could find May. She didn’t know where to go, so she ran back to the house.

When the police appeared at her door, May told them that the white man never said he was the police. He had been in plainclothes. He never said he was the police. How was she supposed to know? Was she to treat every white man like he was the law? Nothing she said made a difference. She tried to explain. Kid, her husband—his real name was Arthur Harris—was just trying to defend her. They asked her who did the cutting. She hadn’t seen the fight, but she knew it was Kid. He was the only one interested in her; the only one who cared if a white man tried to drag her off the street or send her to jail because every black woman was a prostitute in the eyes of the law. Didn’t she have no rights? “When you lose control of your body, you have just about lost all you have in this world.”

She didn’t know where Arthur Harris was hiding. When Officer Thorpe was stabbed, why did you watch and do nothing? The cops dragged her back to the corner. Thorpe was bleeding in the street. The other flatfoot called his name. Thorpe, is this the one? He looked up at May and said, That’s the one. They arrested her for prostitution and then took her to the Tombs. When the following day the newspapers reported that a Negro, Arthur Harris, had murdered a police officer in the Tenderloin, they identified her by name, followed by indictments and qualifiers like “would-be wife,” “girlfriend,” “common-law-wife,” “negress,” and “wench.” Her guilt was established with the words “loitering” and “soliciting.” Description condemned her: dissolute, criminal, and promiscuous.

May Enoch passes as a wife, but they didn’t say what she was, like she was nothing at all. It was in the New-York Tribune for everyone to see. Passing for a wife or acting like one was not the same as being one. Love not bound by the law and sanctioned by the city clerk’s seal had no standing. The district attorney never failed to describe her as a prostitute and Arthur Harris as a rapist. It didn’t matter that there was no evidence for either charge. The white world had made the rules about how to be a man, how to be a woman, how to live intimately, and May and Kid lived outside those rules. Everyone kept asking the same questions: Why was she out after midnight by herself? Why had she waited on the corner after she had spoken with her husband? What exactly did the officer say to her and what was her reply? Why didn’t she do anything to stop her consort, to stop Arthur Harris, once Thorpe was sprawled in the street?

It became apparent that she was guilty too. Her crime was moving through the city and taking up public space; his was the belief that he had a right to defend them from a white man’s violence. Other black folks agreed. If their refusal to submit and battle with the law were celebrated or memorialized in The Ballad of Arthur Harris or May Enoch’s Rag, such tunes have been forgotten.

You saw he had my woman.

I fixed that son of a bitch didn’t I?

That fellow who hit me.

He tried to lock up my woman.

I fixed that son of a bitch.

“He didn’t say nothing to me, he took hold of me—this officer did. Arthur stepped up before he had a chance. I had just got done talking with Arthur as soon as the officer placed his hands on me. Arthur said, ‘What are you doing that for? She ain’t done anything.’ The officer let go of me and grabs him. Then a man by the name of George told me to go up to the house. . . . Twenty minutes after that two officers came for me.”

Sam Palmetto said, “There is a man got your woman.”

Kid said, “What are you doing to her?”

Kid pushed Thorpe’s hands away; then Thorpe grabbed him.

“I’ll take you,” Thorpe said, seizing Kid by the coat collar.

Then Thorpe hit Kid with his club.

Then the blows fell on Kid’s face.

Then there was a scuffle.

Then Thorpe hit him for the third time with the club.

Then Kid reached for a knife.

Then the white man fell into the gutter.

You saw he had my woman. I fixed that son of a bitch didn’t I?

On the steps of the house where Thorpe’s body lay for viewing, one of the mourners, a white woman overcome with grief, cried out, “Get all the black bastards.” The crowd of police officers, and the friends and relatives of Thorpe, seized the first Negro they saw—a seventeen-year-old on his way home from work. Other white folks who didn’t give a damn about Thorpe and had little regard for the police joined the mob intent on beating, maiming, and killing. White women shouted and cursed, inciting vengeance and stoking the fury of their men. “These coons have run the avenue long enough.” “Lynch the niggers!” “Kill the black sons of bitches!” “Give us a coon and we’ll lynch him!” The New York Herald reported: “At every street corner white men had gathered, and the general theme of conversation was that the blacks had had too many privileges in the city, that they had abused them, and that the time had come to teach them a lesson. . . . It was asserted on every side that [Negroes] had been entirely too bold, and had assumed improper sway in Sixth, Seventh and Eighth Avenues and that the white must assert themselves.” White men beat Negroes in the street, pulled them from streetcars, and broke into their homes, determined to quash and extinguish this improper sway, this black swagger betraying the sense that they were at least as good as any white man. Maybe Kid did want to be “the coolest monster on the corner.”

Three days of white violence engulfed the city. After the rout abated, the Reverend William Brooks condemned the police who had goaded the white mob, orchestrating and directing the violence and encouraging brutality as civic duty. Brooks asserted that the Negroes would not suffer such injustice passively or quietly. In his remarks to the press, he didn’t mention May Enoch’s name, but spoke of decent and upstanding folks. They were citizens and would not stand for this blatant disregard of the law; they would not succumb to the white mob and the force of lynch law. Negroes would tell their story so the whole world would know; and even if the police didn’t bother to take their testimony they would record it. When the Reverend Brooks and the Citizens’ Protective League assembled the pamphlet Story of the Riot, May Enoch’s story was nowhere to be found. She was mentioned in passing as the wife of Arthur Harris and otherwise merited little attention. Kid was the only one who cared about her. The League feared dissolute types like May and Kid. Too loud women loitering on street corners and black men with too much swagger would confuse the matter, defuse the righteous anger about what had been done to decent black folks, innocent, law-abiding, and respectable people. She and Kid were on the other side of that line.

It was as if what had happened to May was in a different class than the terrible things the police had done to all those other Negroes, as if good and decent folks had suffered because of them, because of her. Was it Arthur Harris who incited the mob? Was she responsible in the end because he tried to protect her? Was the blood of every Negro battered and brutalized by the police and the white mob to be blamed on her? She was as bad as Kid, and everyone concurred what he had done was terrible. He had tried to defend his wife; he had refused to be beaten like a dog. May had been standing on the corner waiting for him to have a drink and finish a cigar. Was that a crime? Was the knife in her hand, too? He had done it to protect her. Was she glad he had fixed that son of a bitch? Glad that he refused to stand by idly while a white man grabbed her? Proud that he resisted and “resolved to sell his life as dearly as possible,” like Robert Charles battling the police and the white mob in New Orleans a few weeks earlier? If courage made him an outlaw, so be it.

The city rocked with violence as May Enoch waited in a small cell in the Tombs. Every blow the police delivered to black mothers in the company of their children, every colored woman and girl cursed as a black bitch or wench, every daughter and sister and grandmother manhandled and paraded through the streets in their nightclothes and undergarments, every indignity hurled at them—was intended to make them pay for what Kid had done and for the dangerous thought incited by a black man who had raised his hand and dared strike back. All of them, the newcomers and natives, the disorderly Negroes and the established ones, would pay for what Arthur Harris had done.

For four days, all colored people in the city were to answer for May Enoch and Kid. He was still a fugitive. Until he was captured, all Negroes would suffer the violence intended for him. When Annie Hamer exited the Seventh Avenue streetcar, the mob surrounded her. She was instantly struck in the mouth with a brick. As police officers surrounded her, she was separated from her husband, and did not know what became of him until three the next morning, when he came home all covered with blood. On the same night two police officers in plainclothes broke into the home of Elizabeth Mitchell at half past eleven. When Kate Jackson heard the pounding on the front door, she feared that the white mob would harm her and her children, maybe murder them. “She caught up her youngest child (three years old) in her arms, and in her frenzy and fright jumped out of the window onto a shed . . . the child still in her arms.” She was bruised, unable to walk, but at least they were alive. Rosa Lewis was sitting on the front stoop of her building with her husband and neighbors when a police officer walked by and ordered them inside and threatened to beat anyone who didn’t move. She obeyed, preferring not to risk a broken jaw or bashed skull. “I had reached the foot of the stairs leading up to my rooms when the officer, who had rushed into the hallway, struck me over the back with his club.”

Irene Wells was sitting on the front stoop with her three children, as were her white neighbors. On any warm night, folks relaxed on the front steps and waited for a breeze. At eleven thirty p.m., police moved through the block. One stepped toward her and said, “Get in there, you black son of a bitch” and struck her across the right hip. When she ran into the building with her children, the cop followed her in, “striking at her until she reached the top step.” He threatened to strike her again if she left home. At 2:55 a.m., police officers passed through the block again, clubbing colored people. It didn’t make a damn bit of difference if you were a woman or a man.

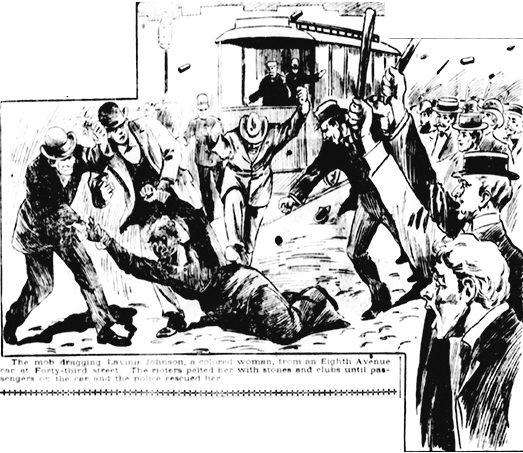

Those naive enough to appeal to the police for protection were clubbed and beaten by officers, then arrested. Once inside the precinct, they were beaten again before being locked away in jail cells. The mob and the police were united in their effort to “treat niggers the same as down South.” It was impossible to distinguish the mob from the law. The threats and curses were shared: “We’re going to make it hot for you niggers!” “Kill every damned one of the niggers!” “Set the House afire!” When the police forced their way into Lucy Jones’s apartment at 341 West 36th Street, they shouted, “You God damned black son of a bitch, you know a lot about this damned shooting, and if you don’t tell me I’ll blow the brains out of you.” She had watched as the police had beaten and dragged away her neighbor, William Seymour, who lived in the flat next door to hers. He had been wearing only his undershirt when they pulled him outside. The added humiliation of his nakedness produced a collective state of shame. One of her white neighbors caught sight of Lucy peering from the window. He shouted, “Look at the damned nigger wench looking out of the window. Shoot her! Shoot her!” The scene of the mob dragging Lavinie Johnson from the Eighth Avenue streetcar was illustrated in the New York World, but her face was a black mask, featureless and indistinct; the folds and creases in the trousers of the man kicking her back were rendered more precisely than her expression. The excess of dark pigment blotted her out, making her a shadow.

When they seized Nettie Threewitts from her house, she protested, “You are not going to take me without any clothes on?” “You don’t need any clothes,” the police replied, shoving her down the stairs and onto the stoop, where she was in full public display. When the patrol wagon came, the officers cursed her for sport. They called her a black bitch, laughing and enjoying her humiliation. “One of them struck me in the head with his fist, another one deliberately spit in my face, and another took his helmet and jabbed it into my eye.” One suggested they “burn up all the nigger wenches.” Another shouted, “Shut up, you’re a whore, the same as the rest of them.” The black women of the Tenderloin came before the law as May had, as future criminals, prostitutes, nobodies.

People were crying, “O Lord! O Lord! don’t hit me! don’t hit me!” Lord Help Me! If he made a way. If he brought them out. Women pleaded for their fathers and husbands and friends only to be beaten and cursed and clubbed alongside them. The police did more harm than the mob. Look, a Nigger! Lynch the Nigger! Kill the Nigger! Such were the rallying cries of neighbors and citizens. Less than three weeks after the brutality in New Orleans and a year after Sam Hose was lynched in Georgia, burned and mutilated before a crowd of over two thousand, white men gathered in the streets of New York, determined to instruct Negroes about the limits of liberty and intent on quashing the arrogance and swagger that evidenced a misguided belief in equality. Mob rule in the Tenderloin was as vicious and indiscriminate. North and south were just directions on a map, not placeholders that ensured freedom or safety from the police and the white mob.

Reverend Brooks defended Arthur Harris, but he would not call him a hero, as Ida Wells had in her defense of Robert Charles after he killed seven white men, including four police officers in New Orleans in self-defense. Nor did he assert his right to self-defense. Reverend Brooks and the self-appointed leaders of the race hoped that the banner of innocence might protect them from orchestrated and random brutality. The Citizens’ Protective League repeated to no avail, “We are citizens, even though we are black, and there should be some redress in the courts for all we have suffered. The city should be responsible for the brutality that has been practiced upon innocent people. . . . If we cannot get [redress] now, when can we get it?” When can we get it? This question would be repeated endlessly over the course of the century.

The terror unleashed in the heart of the city’s blackest and most populated ward brought to mind the Draft Riots of 1863, so open was the hatred, so voracious the violence and the fury. Between 1890 and 1900, New York City’s black population doubled, and the white folks living in closest proximity greatly resented their presence. The more than forty thousand Negroes made up less than 2 percent of the population, but the threat represented by their presence was magnified a thousandfold. The effects of the riot in the Tenderloin were far-reaching and accelerated the racial segregation that more and more defined the city. The violence was a major catalyst in the making of Harlem. After being attacked by their white neighbors, black New Yorkers sought protection by huddling with their own. The daily racial assaults and clashes in downtown, coupled with the availability of housing in Harlem, spurred this migration within the city. By 1915 at least eighty percent of black New Yorkers lived in Harlem. The numbers steadily increased despite the attempt of “The Save Harlem Committee” organized by Anglo Saxon Realty to stanch the flood of black folks. What the riot made clear was that the color line was hardening and that segregation and antiblack racism were not only augmented by way of state and federal policy, but also stoked by the antipathy and the psychic investment of even the poorest whites in black subordination and servility. Their ancestors had never owned slaves, yet they regarded Negroes as “slaves of society.” What stake had survivors of famine and immiseration in recreating the plantation in the city, in gratuitous violence directed at any and every black face, in defending the color line as if their very lives depended on it, as if their sense of self was anchored in this capacity to injure others? What stake had the survivors of pogrom in excluding Negroes from the factory floor and refusing to hire them? As four days in August made plain, the enclosure of the Black Belt was to be as sharply defined in northern cities as it had been in the south; poverty, state violence, extralegal terror, and antiblack racism were essential to maintaining the new racial order.

As if anticipating what the future held, as if the Red Summer of 1919 and the riots in Harlem in 1915, 1935, and 1943, and Watts in 1965 or Detroit in 1967, were already within his sights, Paul Laurence Dunbar advised the Negroes of the Tenderloin not to do anything to stir up trouble and invite the wrath of white folks. On a tour of the homes of Negroes in the riot district, he counseled them “to stay at home and refrain from doing anything that might incite the rioting element to break out again,” as if white rage were a storm that had landed in the Tenderloin, or a spate of bad weather that they could wait out if only they were patient. Worn out after his encounter with their bruised and battered lives and mouthing what he was expected to say but was hard-pressed to believe, he refreshed himself at a saloon at Thirty-Second Street and Sixth Avenue. The Negro bard passed out—a condition with which he was not unfamiliar—except in this instance he claimed the blackout was the consequence not of excessive drinking, but of being drugged in the saloon. When he awoke the next day, his watch was missing, as well as a $150 diamond ring and forty dollars in cash. His personal history of debauchery and wastefulness failed to temper the stern lessons he offered the lower ranks of the race, whose lives he had made into lyric securing his fame. His song for the riot was belated, and penned when even a fool was capable of reading the handwriting on the wall, listening for the deep impassioned cry.