MADE TO BURN

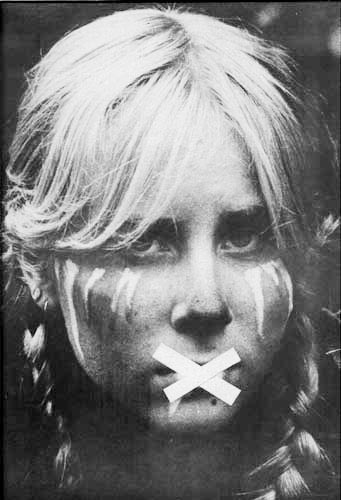

The first image I pinned up, to spark inspiration for what would eventually be a novel, was of a woman with tape over her mouth. She floated above my desk with a grave, almost murderous look, war paint on her cheeks, blond braids framing her face, the braids a frolicsome countertone to her intensity. The paint on her cheeks, not frolicsome. The streaks of it, dripping down, were cold, white shards, as if her face were faceted in icicles. I didn’t think much about the tape over her mouth (which is actually Band-Aids over the photograph, and not over her lips themselves). This image ended up on the jacket of The Flamethrowers, whose first-person narrator is a young blond woman. A creature of language, silenced.

The second image I pinned up was of Ducati engineer Fabio Taglioni standing behind a 1971 750 GT. The Ducati is in metal-flake orange, Taglioni in double-knit Brioni. I didn’t have an image of a girl on a motorcycle, although the book opens with the narrator riding one in the Bonneville land speed trials. She isn’t me. But her sense of the heat and the light at the Salt Flats is mine.

The young woman in war paint was from an archival document of 1970s Italy, and she symbolized for me the insurrectionary foment that overtook the country in that decade. “Autonomia” was the term for this foment, the movement of the 1970s, a loose wave of people all over Italy who came together for various reasons at various times to engage in illegality and play and to find a way to act, to build forms of togetherness in a country whose working class was impotent and whose sub-working class was fed up with work, by turns joyous and full of rage, ready to revolt, which they did. There were multiple layers, of which the most shadowy, clandestine, and violent (and paradoxically, the most visible and sensational) were the Red Brigades. The Italian seventies had seemed a logical subject for fiction, on account of the fact that I kept stumbling upon its lore. It all began when I met a mysterious and magnetic woman who didn’t say much, and who, when I naively asked her what she did, what she was interested in, stared at me and said, “Niente.” She had been the girlfriend of a “third-wave” Red Brigades terrorist, I learned. Her “niente” did not mean “nothing.” It meant, I don’t engage in what you’d call work. Or interests. I might add that I met this woman in a house on Lake Como that was filled with someone’s mother’s Fascist memorabilia, busts of Mussolini, D’Annunzian slogans chiseled into marble.

Which connects to the third image I pinned up as I wrote, of two proper-looking gentlemen in a World War I–era motorized contraption, an arcane cycle and bullet-shaped sidecar. Of the pair, the man in the sidecar, if passively at the mercy of the one over the handlebars, looks more self-possessed. He looks, actually, like F. T. Marinetti. I pretended that he was, and asked myself, Why did the Futurists never actually build anything? They drew vehicles on paper. They called war the world’s only hygiene. But they had no relation to engineering and factories, to machines or munitions—except that a few of them lost limbs, or lives, in the war. But so did a lot of non-Futurists.

There are two central threads to The Flamethrowers: Italy in 1977, the crest of the movement, and New York at that time, a period I’m old enough to have seen and which has long fascinated me, when the city had a Detroit-like feel, was drained of money and its manufacturing base, and piled up with garbage. Parts of downtown became liberated zones of abandonment, populated by artists and criminals. The blackout of 1977 has a special place in my heart—the “bad” blackout, compared to 1965, the “good” blackout, when everyone in the housing projects behaved, an event whose textures DeLillo rendered so memorably in Underworld.

I wanted to conjure New York as an environment of energies, sounds, sensations. Not as a backdrop, a place that could resolve into history and sociology and urbanism, but rather as an entity that could not be reduced because it had become a character, in the manner that a fully complex character in fiction isn’t reducible to cause, reasons, event. I looked at a lot of photographs and other evidentiary traces of downtown New York and art of the mid-1970s. Maybe a person is a tainted magnet and nothing is by chance, but what I kept finding were nude women and guns. The group Up Against the Wall Motherfucker, which figures in the novel, papered the Lower East Side in the late 1960s with posters that said, “We’re looking for people who like to draw,” with an image of a revolver. I had already encountered plenty of guns in researching Italy—the more militant elements of the Autonomist movement had an official weapon, the Walther P38, which could be blithely denoted with the thumb out, pointer finger angled up. I would scan the images of rallies in Rome, a hundred thousand people, among whom a tenth, I was told by people who had been there, were armed. Ten thousand individuals on the streets of Rome with guns in their pockets.

Among New York artists, I hadn’t expected guns, and yet that’s what I encountered: lots of guns and, as I said, lots of nude women. Occasionally in the same image: Hannah Wilke in strappy heels holding a petite purse pistol—like Honey West, but naked. Mostly it was men posing with the guns: William Burroughs, William Eggleston, Sandro Chia, Richard Serra. Warhol’s gun drawings. Chris Burden out in Los Angeles having a friend shoot him. And women with their clothes off: Carolee Schneemann, Hannah Wilke, Francesca Woodman, Ana Mendieta, Marina Abramović, who was both nude and with a loaded gun pointed at her head (by a man).

What does all this mean? Many things, I’m sure, but for starters, it means people were getting out of the studio. Art was now about acts not sellable; it was about gestures and bodies. It was freedom, a realm where a guy could shoot off his rifle. Ride his motorcycle over a dry lakebed. Put a bunch of stuff on the floor—dirt, for instance, or lumber. Drive a forklift into a museum, or a functional race car.

But that’s art history. For the purposes of a novel, what did it mean? I was faced with the pleasure and headache of somehow stitching together the pistols and the nude women as defining features of a fictional realm, and one in which the female narrator, who has the last word, and technically all words, is nevertheless continually overrun, effaced, and silenced by the very masculine world of the novel she inhabits—a contradiction I had to navigate, just as I had to find a way to merge what were by nature static and iconic images into a stream of life, real narrative life.

As I wrote, events from my time, my life, began to echo those in the book, as if I were inside a game of call-and-response. While I wrote fiction about ultraleft subversives, The Coming Insurrection, a book written by an anonymous French collective, was published in the United States and its authors were arrested in France. As I wrote about riots, they were exploding in Greece. As I wrote about looting, it was rampant in London, after the killing, by police, of Mark Duggan. The Occupy movement was born on the University of California campuses, and then reborn as a worldwide phenomenon, and by the time I needed to describe the effects of tear gas for a novel about the 1970s, all I had to do was walk downtown to Occupy’s encampment, or watch live feeds from Oakland, California.

In 1978, the Red Brigades killed Aldo Moro, the leader of the Christian Democrats and former prime minister of Italy. That same year, Guy Debord, founder of the Situationist International, made his final film, In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni, its title a famous Latin palindrome, translatable as “we turn in the night and are consumed by fire.” The film includes many still images that I looked at and into as I wrote. Debord’s relationship to women and girls is so strange. He’s suggesting they’ve been used for banal consumer culture—to sell soap, for instance—and yet surely he enjoys seeing them in their bikinis, their young flesh and sweet smiles, as he edits them into the frame.

As I was working on my novel, I encountered a woman who was friends with the only Situationist not expelled from the group by Debord, the enigmatic, semi-infamous Gianfranco Sanguinetti. “What is he up to?” I asked a little too eagerly. “What does he do now?” She shrugged and, coolly, disdainfully, said, “He lives.” Later, I learned that Sanguinetti had a large inheritance, and that he mostly tended “his vineyards and his orchards.” In addition, I learned that those who “live” can afford to.

A few more films besides Debord’s that were important sources: Barbara Loden’s Wanda, about a woman who isn’t afraid to throw her life away. Chantal Akerman’s News from Home, in which the camera wanders the deserted streets of Lower Manhattan. Alberto Grifi and Massimo Sarchielli’s Anna, the mother of all films about Italy in the 1970s. Also, a filmic fact: that Taxi Driver was re-rated from X to R after Scorsese scaled back the brightness of reds in the film printing. Michel Auder’s The Feature, which I saw at Anthology Film Archives, just me and one old man crinkling a paper bag in the theater, as Auder spent Cindy Sherman’s money on prostitutes, playing himself in a despicable but brilliant game. Before he was married to Cindy Sherman, Auder had been with Viva, the Warhol superstar. Viva later dated the photographer William Eggleston, when she was living at the Chelsea Hotel, just after he made Stranded in Canton, in which his Memphis friends wave guns and hold forth in Quaalude slurs.

An appeal to images is a demand for love. We want something more than just their mute glory. We want them to give up a clue, a key, a way to cut open a space, cut into a register, locate a tone, without which the novelist is lost.

It was with images that I began The Flamethrowers. By the time I finished, I found myself with a large stash.

Jack Goldstein, The Murder, 1977, 331/3 RPM.

This twelve-minute record is a montage of sound effects—mostly breaking glass, pouring rain, and thunder. The artist Jack Goldstein had all the right ingredients for myth: brilliant, cool, mysterious. He was hugely influential but ended up living in a trailer in East LA, selling ice cream from a truck. The ice cream once melted completely when he had to wait in line for methadone, but he refroze it and sold it anyway. He died in 2003, and so his body of work is now, sadly, a bounded set.

William Eggleston, still from Stranded in Canton, 1974.

There’s a scene in Stranded in Canton in which Memphis local Jim Dickinson, who produced an album for the band Big Star, leers into the camera in rhinestone-rimmed glasses. He and an unnamed woman kiss, but they are high on Quaaludes and sort of miss each other’s lips. He’s wearing an ugly tuxedo, as if he’s on his way to a high school prom. I have watched Stranded in Canton many times; it stays mysterious. There are two different dentists who each figure prominently, one shirtless, both drunk. Those dentists are dead now, as are many, if not most, of the people in the video. According to the credits, a not insignificant portion of them were murders or suicides. Neither tragic nor legendary, I myself will never die.

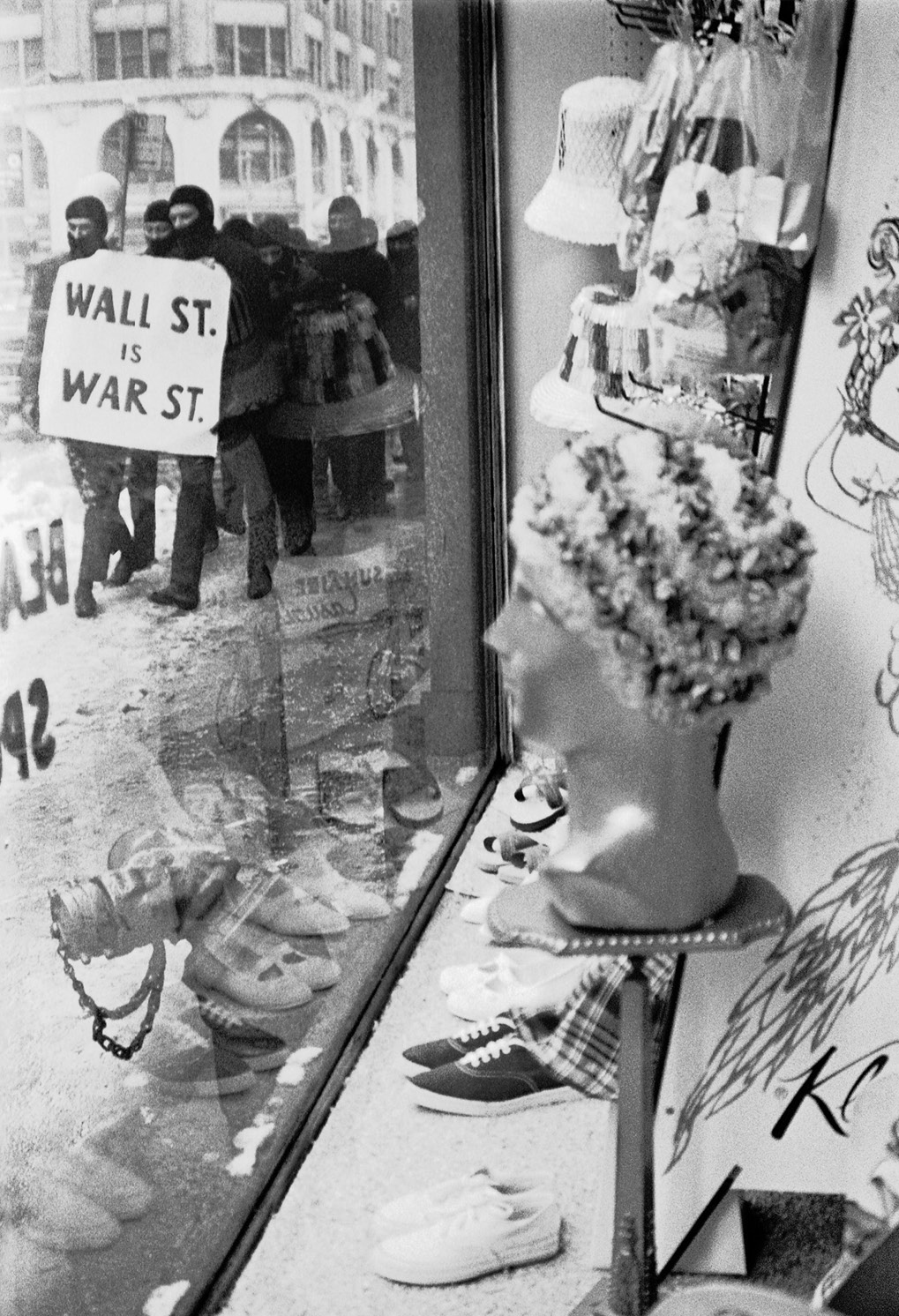

Larry Fink, Black Mask, 1967.

Black Mask was a Dada-inspired antiwar movement that intervened in culture and politics and later morphed into Up Against the Wall Motherfucker, “a street gang with an analysis.” They ran soup kitchens and a free store and tried to empower and motivate the disenfranchised. Their legacy made way for the great culture of East Village artists’ squats like the Gas Station on Avenue B.

Danny Lyon, 88 Gold Street, 1967.

The same year Larry Fink photographed Black Mask on Wall Street, Danny Lyon methodically captured with a view camera the vast demolition of Lower Manhattan, much of it coming down for the construction of the Twin Towers. Factories and warehouses to be replaced by finance, which gives literal shape to a significant transformation of the seventies: the death of American manufacturing.

Andy Warhol, still from Screen Test: Virginia Tusi, 1965.

Who is she? No one seems to know. “A young woman identified only as Virginia Tusi,” according to the catalogue raisonné. She was included in Warhol’s Thirteen Most Beautiful Women along with Susanne De Maria and Julie Judd—the exceptionally pretty wives of Walter De Maria and Donald Judd. Warhol’s two favorite kinds of people were beautiful people and the American upper classes. When those were combined into one person, such as Edie Sedgwick: bliss. One of the more striking men that Warhol filmed in 1965 was in the audience when I saw a program of Screen Tests in 2011. This man, a beard now tumbling down his chin, big belly protruding from his open blazer, shared anecdotes. “Warhol wanted me to flex my jaw,” he said. And, “Edie was a real bitch.” It might be better if Virginia Tusi just keeps beaming resplendently from her Screen Test, a mystery of mute loveliness.

Julie Buck and Karin Segal, China Girl #56, ca. 1970s, restored and transferred 2005.

China Girls, whose faces were used to adjust color densities in film processing, were mostly secretaries who worked in the film labs—regular women who appeared on leader that was distributed all over the world. It’s not clear why they had that rather racist moniker; some say the original ones were Asian, and others speculate that a particular secretary who posed for film leader was a habitual server of tea (which makes the name seem even more problematic). China Girls were used indexically to calibrate skin tone, meaning white skin tone; racial bias is right there on the leader, in the form of a smiling secretary. In France, they were “les lilis.” If the projectionist loaded the film correctly, you didn’t see the China Girl. And if you did see her, she flashed by so quickly she was only a blur. They were ubiquitous and yet invisible, a thing in the margin that was central to each film, these nameless women who, as legend has it, were traded among film technicians and projectionists like baseball cards.

Lee Lozano, Punch, Peek & Feel, 1967.

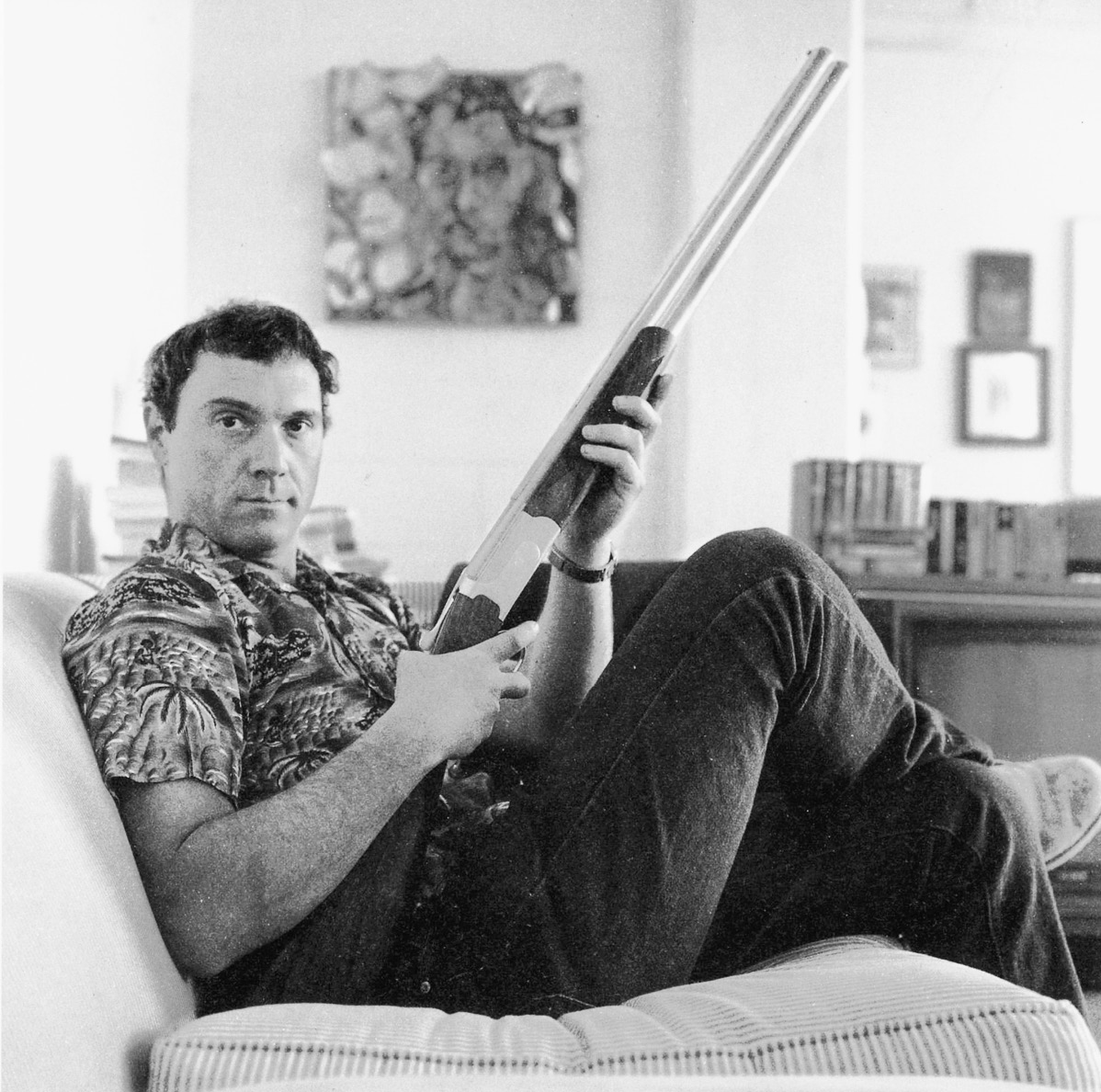

Allen Ginsberg, Sandro Chia, 1985.

“In a serious confrontation, I’d take a shotgun, any day. It’s a much more formidable and effective weapon than the handgun, unless it’s a hand shotgun. I’d like to see more of those,” wrote William Burroughs. The artist Sandro Chia had been firing at targets with Burroughs in Rhinebeck, New York, when this photograph by Allen Ginsberg was taken.

[Left] Lee Lozano was a tough and uncompromising person, celebrated by her male contemporaries for her conceptually driven paintings and the way she collapsed art into life. She had a solo show at the Whitney in 1970. In 1971, for her piece Decide to Boycott Women, she did just that: she didn’t speak to women for the next twenty-eight years, right up until her death.

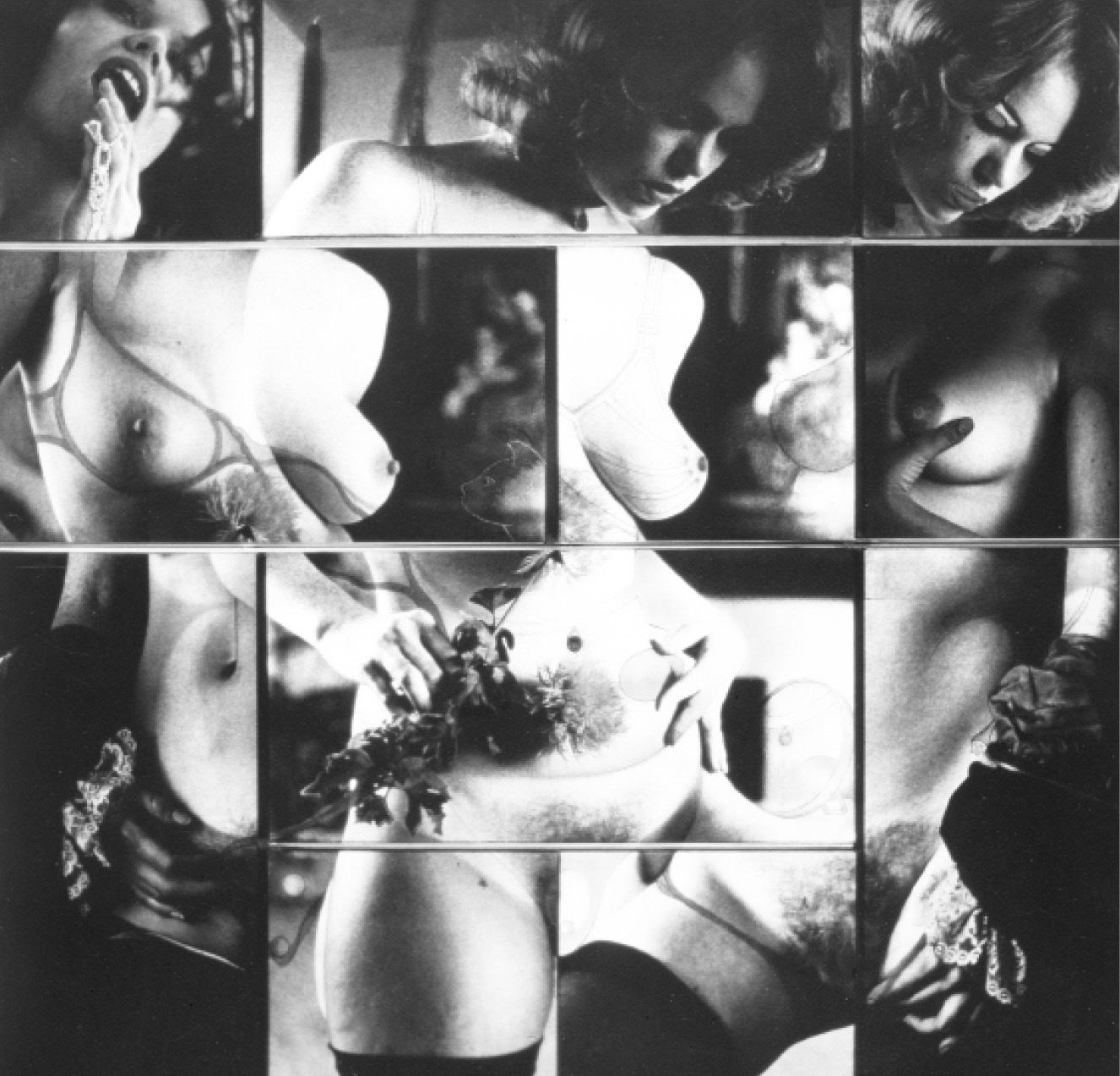

Robert Heinecken, Cliché Vary: Autoeroticism, 1974.

The sweet innocence of the McLuhan seventies. By the 1980s, when I was a teenager, I carried around a copy of Subliminal Seduction: Are You Being Sexually Aroused by This Picture? and thought I was being very ironic and clever. The culture by that point was already using the ability to decode to sell us to ourselves in even more effective ways. Selling us sex. Even as sex was, is, and will always be, one of the few things people can offer each other for free.

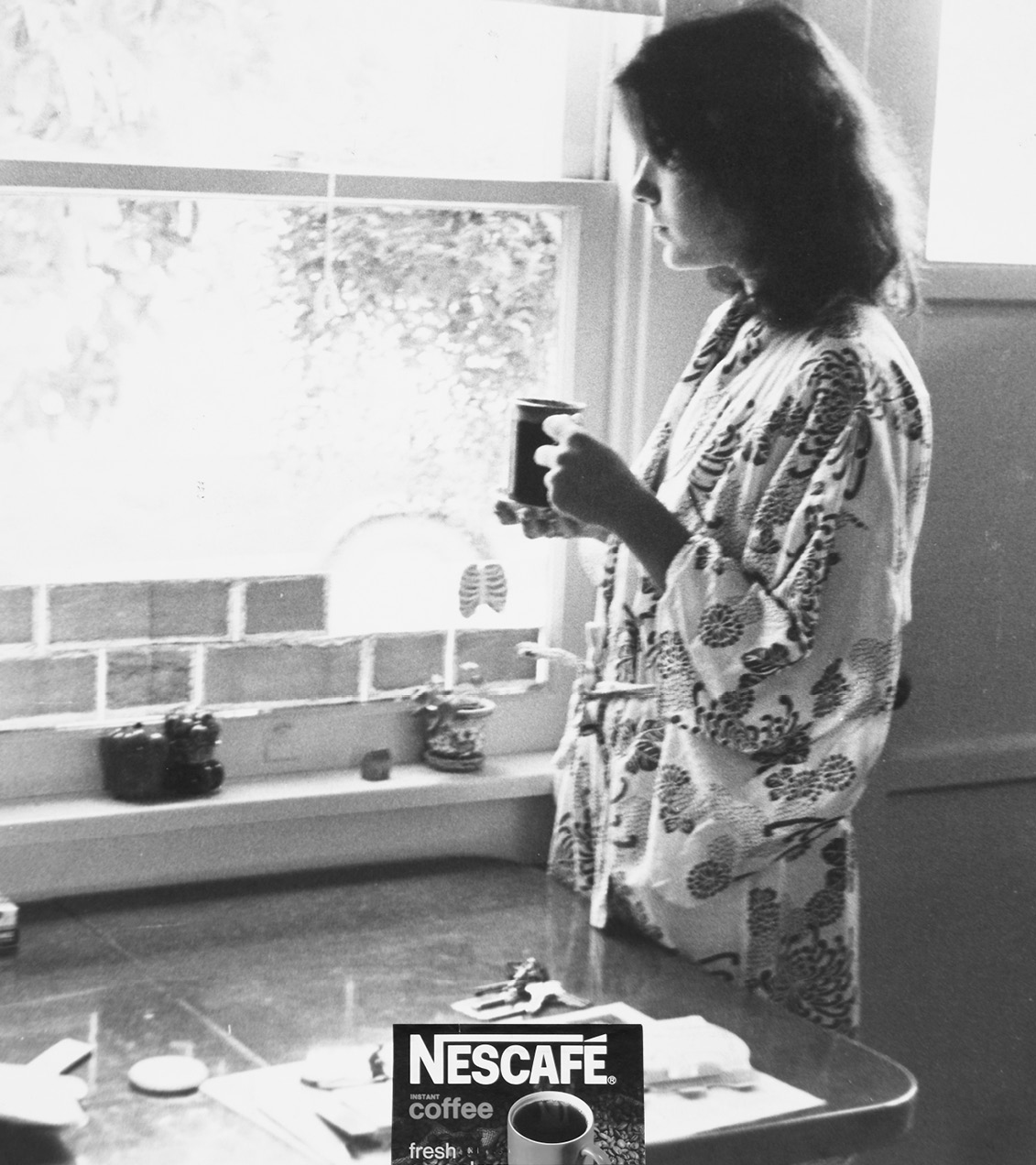

David Salle, The Coffee Drinkers, 1973.

She’s having a quiet, contemplative moment in morning light. She’s selling coffee. Or coffee’s selling her, as her, or as… lifestyle? Something feminine, calming, pure? “Images that understand us” was a phrase coined by David Salle and James Welling. Salle, as a twenty-one-year-old student, made this prescient series—well before we came to know work by Richard Prince or Cindy Sherman—by photographing four women in his life (among them his girlfriend and mother) and gluing on the Nescafé label.

Gabriele Basilico, Contact, 1984.

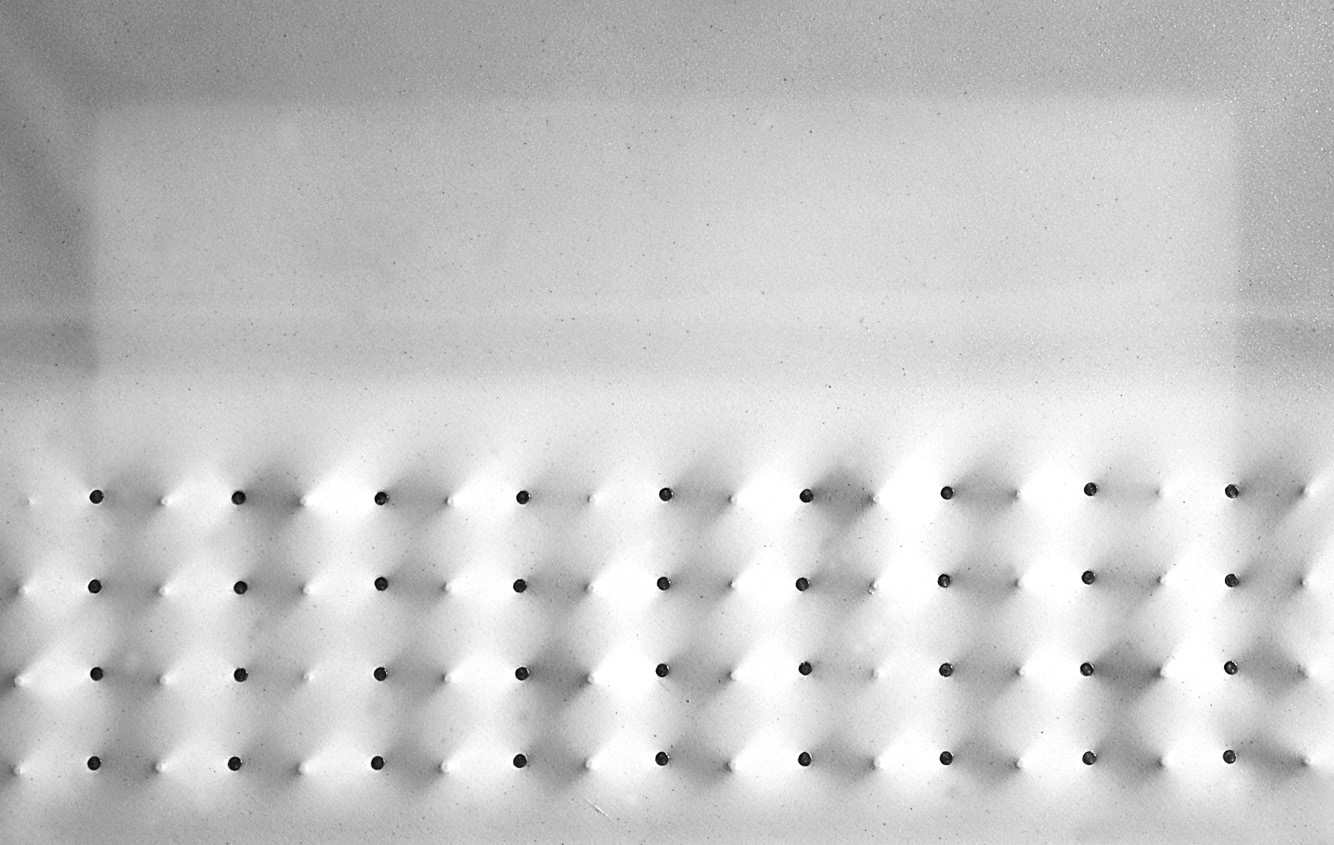

“Putting together chairs and bottoms was very enjoyable for me,” Gabriele Basilico said of his series Contact. He called the residual marks from this process “provisional relief tattoos.” But tattoos of what? Modernism, as painless as modernism looks but never is. The link between violence and modernism is everywhere but too broad to get into in the form of a caption. It’s something more like a life’s work. Someone’s, anyhow, if not mine.

Enrico Castellani, Superficie, 2008.

Enrico Castellani, a younger contemporary of Lucio Fontana and Alberto Burri, was the first person in Italy targeted in the massive sweep of arrests in the seventies. Castellani seems to have circulated among leftists. A recent catalog of his work includes an essay by Adriano Sofri, former leader of the leftist group Lotta Continua, who spent twenty-two years in prison for instigating the assassination of a police captain (Sofri vehemently maintains his innocence).

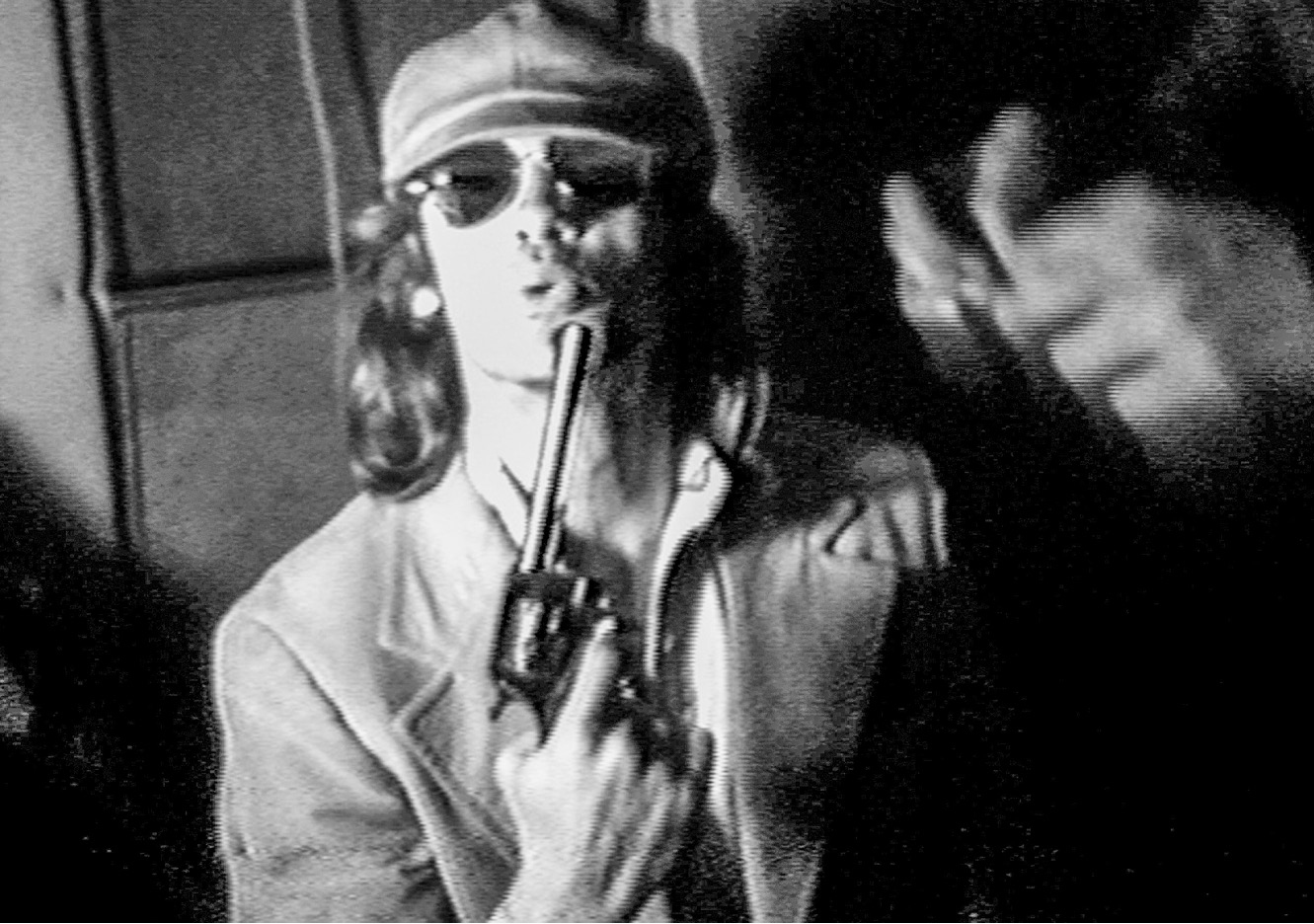

Alberto Grifi and Massimo Sarchielli, still from Anna, 1975.

Later in this book, I write quite a bit about Anna, a homeless, pregnant, drug-addicted teen “adopted” by two male filmmakers in 1970s Rome. The Flamethrowers was in part dedicated to her, and to her disappearance as an act of revolt. An Austrian filmmaker, Constanze Ruhm, a kindred spirit in her interest in Anna, traveled to Sardinia, where Anna was from, to track her down. She’d apparently died in 2004. I would guess that Anna was less interested in the movie about her than I was, than Constanze was. The people I’ve known like Anna—and I’ve known many—they live in the present tense of their lives, not the past. Caught up, mired, and possessed by real time instead of nostalgia.

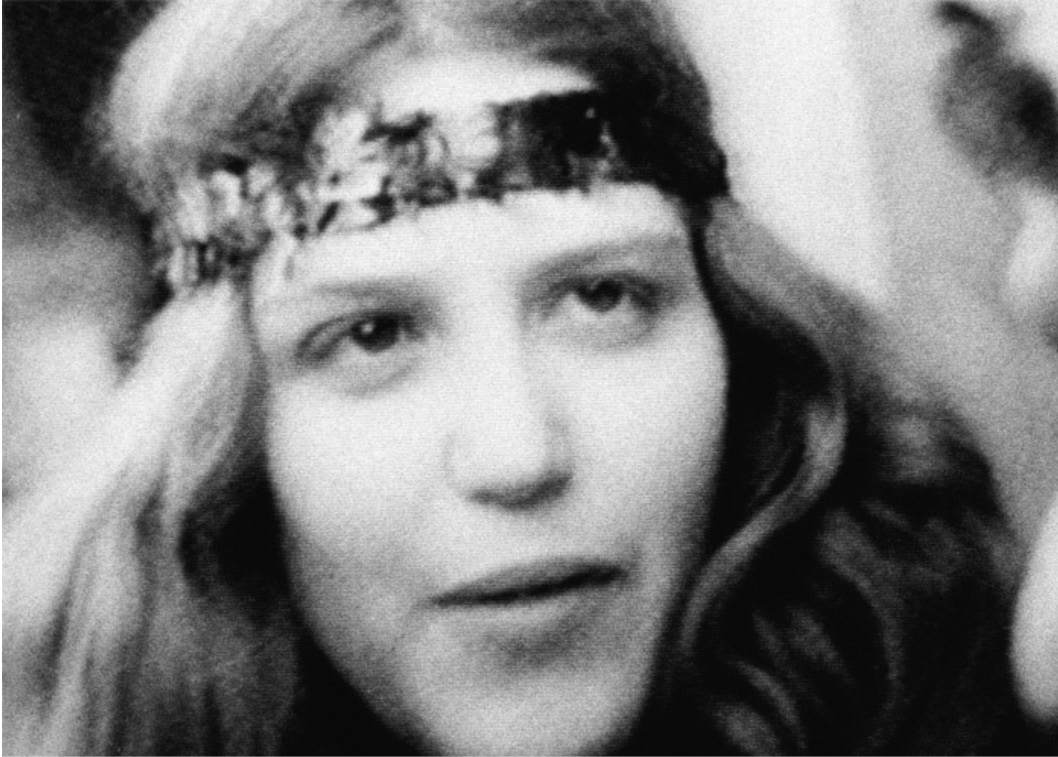

From the cover of I Volsci (March 1980), issue 10.

She doesn’t look Italian, despite having appeared on the cover of an ultraleftist Roman newspaper. Some told me she was German, others that it was the photographer who was German. I’d reached deep into my connections to the older generation in Italy to try to find out who she was. No one could quite remember, from the hazy time of youth when you don’t concern yourself with names and provenance. My publishers thought that the woman, discovering that her photo was on the cover of my book, might complain. Why would she do that? I asked. The response: “Let’s say she changed her life and married a high-powered banker or well-known politician over there in Germany, and she hasn’t told him about her radical past, but your book announces it.” “But that would be a good story,” I said, and they agreed. So far, no one has come forward claiming to have been this girl.

Tano D’Amico, At the Gates of the University, 1977.

Go to Italy and few mention the 1970s, when their country literally almost had a revolution. That explosive era and its joys, traumas, and failures have been all but erased. Luckily, there are some remainders, like the amazing photographs of Tano D’Amico. Here he captures the gates of Sapienza University in Rome on February 17, 1977, when it was occupied by students, as Luciano Lama, leader of the biggest labor union in Italy, came to pay them a visit and was heckled and expelled.

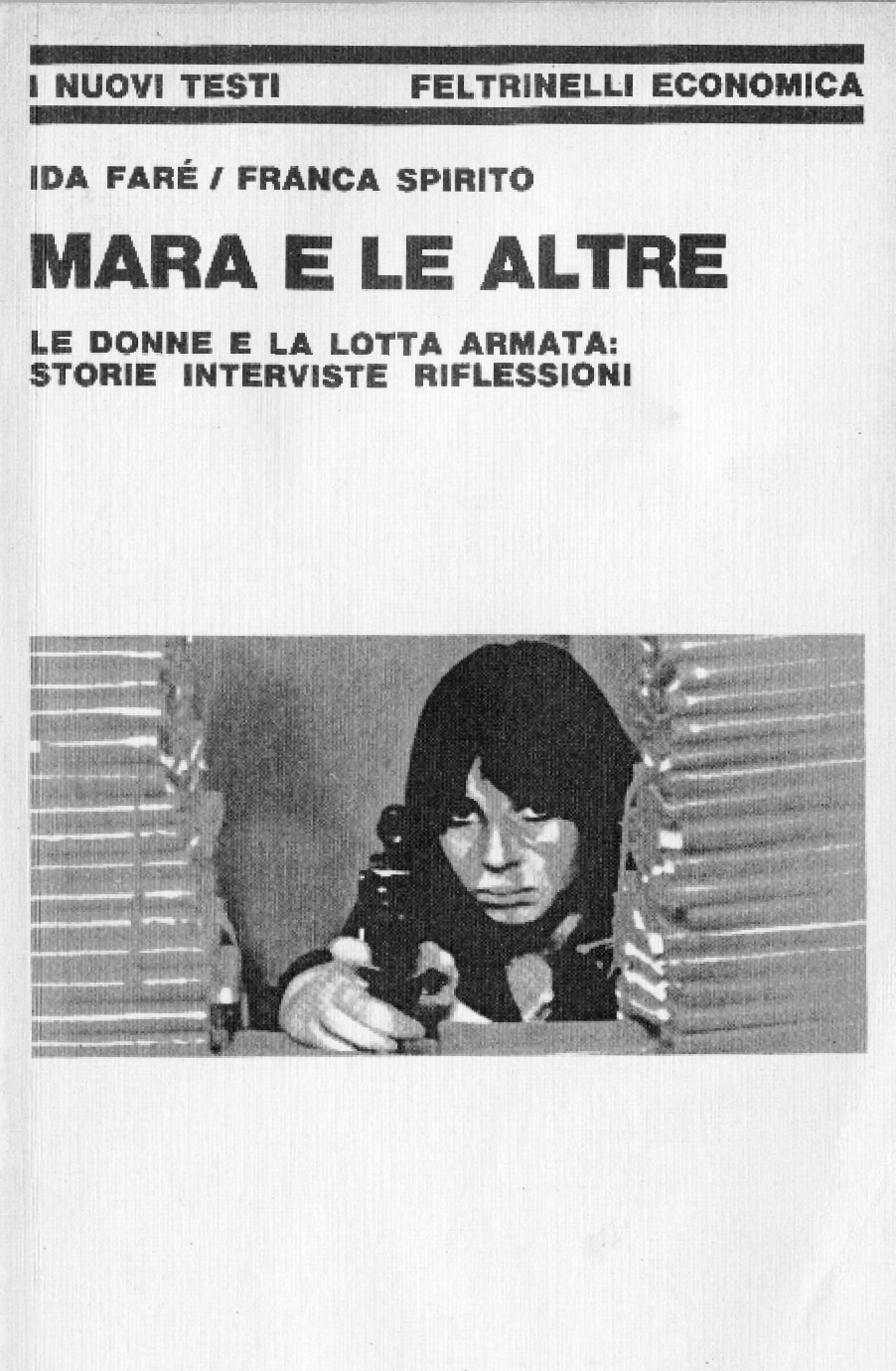

“Mara” is Mara Cagol, a former leader of Italy’s leftist-militant Brigate Rosse (BR). “Le altre” are the militant women in Italy in the 1970s, whose Leninism and bombs were only one small and contested facet of a vast and complex wave of feminist actions that transformed the landscape of Italy. Ida Faré, coauthor of this book, was an important theorist of both feminism and architecture, a professor, activist, writer, and founding member of the Milan Women’s Bookstore Collective. While writing The Flamethrowers, I was invited to the collective’s monthly meeting and dinner. That night, Faré was the appointed host of our discussions. The other women in attendance that evening were all similarly legendary and radical figures of the 1970s. They wore black, chain-smoked, had perfectly coiffed hair, and they called each other gruffly by their last names. At dinner, they simultaneously scolded me for my ignorance and were incredibly generous and warm. Ida Faré died in 2018.

It’s curious that for the cover of this book, an image from Godard’s 1967 film La Chinoise was chosen. Not an image of a real female engaged in armed struggle, of which Italy produced several, but a still from a film where an actress (Juliet Berto) plays a terrorist, crouching behind a machine-gun turret built of stacked copies of Mao’s Little Red Book. The real terrorist, Mara Cagol, successfully broke her husband, fellow BR leader Renato Curcio, from prison in 1975. The same year, she was gunned down in a shoot-out with carabinieri. The founder of Feltrinelli, the press that published this book, had died accidentally in 1972, attempting to sabotage Milan’s power supply.