MOSCOW, OCTOBER 2016

The war in Syria, the conflict in Ukraine with the annexation of Crimea, possible interference in the American elections… So many crises are linked to Russia, so many reasons why the Putin regime turns in on itself to complicate our investigation in the National Archives.

“It is an inopportune moment,” we are told by the different services of the sprawling Russian administration. Next month conditions will be better, after the holidays, the summer holidays, then All Saints… Six months have passed like that. Three more stays in the city of Ivan the Terrible, three return trips between Paris and Moscow, and for what? For nothing? Larisa Rogovaya is still director of GARF, but she’s stopped answering us. Her secretaries have skilfully erected a barrier between her and us. My colleague Lana grew up in this country at a time when it was still called the Soviet Union. She understands the reaction of the Russian authorities. “In the eyes of my compatriots, the West wants to hurt us, it rejects us,” she explains. “Our investigation into Hitler is far from anodyne. The story of the skull is a powerful symbol in Russia; it is the symbol of our suffering during the Second World War, of our resistance and our victory. Since this skull was displayed to the public, its authenticity has frequently been called into question. Part of the glorious past of the Soviet Union is being stolen in this way.” When one of these challenges comes from an American supported by an American university within the context of a television documentary… for the Russians, the fact that the channel is American cannot be a coincidence. It must be an attempt at destabilisation on the part of the former American ally. For the American documentary team, they have no intention of destabilising the Russians. So, over seventy years after May 1945, Washington and Moscow are still disputing the paternity of the final victory over Hitler. And that makes any investigation into the Hitler file so sensitive in Russia. Above all, so complicated. “The human factor.” But Lana won’t let go. She repeats those words out loud like a protecting mantra, a Cabalistic formula. “In my country,” she insists, “you mustn’t act rationally, you must be guided by your instinct and stake everything on the shortcomings of our interlocutors.”

So, the human factor. Since our many official requests have got us nowhere, we’re going to bet everything on luck. Kholzunova Avenue, a smart part of town nestling in a loop of the Moskova, the base of GARF, the State Archives of the Russian Federation. By visiting at regular intervals, we have become intimately acquainted with the weekly guard roster. Tuesday is our favourite. On that day, the checks at reception are carried out by a pleasant soldier. Nothing like the severe and rather limited man with the moustache on Monday, or the big-nosed simpleton on Friday. Petite and always cheerful behind her counter, the guard on Tuesdays always activates the turnstile and lets us through without a problem. On this damp Tuesday in autumn, she doesn’t change her good habits. She suspects the reason for our visit. “It’s still Hitler, isn’t it?” Who doesn’t know about that within GARF? “Which service are you visiting today?” she asks, checking our names in her register. “Ah, Dina, you’re going to see Dina Nikolaevna Nokhotovich? I expect you know where to find her… Straight on, last building at the end of the courtyard…” Lana finishes the phrase for her: “… middle door, fourth floor, first left.” She’s trying to sound relaxed. But she isn’t, and neither am I. We’re staking a lot on this visit. Dina Nokhotovich was there when we studied the skull six months ago with the director of GARF. She had witnessed the scene with one of her colleagues, pale Nikolai. Dina is ageless. Time has ceased its assault on this tiny, energetic woman. Do the gloomy halls of the Russian State Archives conceal some sort of magical power, a bubble in time? Why not. The mere fact of walking all the way up to her office makes us feel as if we are plunging into some bygone era, the past of the totalitarian Soviet utopia. Each step we take sends us ten years backwards. As we climb, the dilapidated state both of the steps and of the walls becomes increasingly apparent. Once we reach the fourth-floor landing, we have gone back forty years. Here we are in the middle of the 1970s. The Brezhnev era. The one in which the head of GARF’s special collection, Dina Nokhotovich, still lives and will live forever. The idea of a face-to-face meeting with this eminent functionary of GARF didn’t immediately occur to us. Our first encounter last April lacked a certain warmth. Discreet, if not entirely silent, passive and then almost hostile in her treatment of us, Dina at first displayed no major interest in our investigation. At least that was how it seemed to us. Her secret had not yet been revealed to us. That only happened very recently, the day after our meeting in late October. We were consulting archived documents at GARF once again. The young archivist was surprised to see us so often. Although she was very shy, she finally plucked up the courage to ask why we were there. Hitler’s skull, his death, the investigation… And the hope of an analysis of the human remains. “The bones? But Dina’s the one who found them.” The skull? Our reaction was so immediate that we startled the young archivist. We didn’t care. We absolutely had to know more. So Dina had found the skull. But how? When? Where?

“You’ll have to ask her,” our informant said, still on the defensive. “Here she is now, you can ask her directly.” The head of the special collection, our new friend Dina, was about to finish a day that had started so early that she was exhausted already. While the elderly archivist closed a thick armoured door–one of the many doors leading to the shelves of the archives–Lana put into practice her theory of the “human factor.” A failure. Dina resisted. What did we want from her now? She didn’t have time. She didn’t want to. Lana lost her footing; she couldn’t find the slightest angle, the slightest foothold to cling to. What about vanity? That might work. “Isn’t it strange that you’re never mentioned in all those articles about Hitler’s skull?” I asked Lana to translate word for word. She was acquitting herself to perfection. I continued without letting Dina reply: “We’ve just been told that the skull was rediscovered thanks to you! Your discovery is historical, ground-breaking. The public needs to know.” “Da, da.” Dina replied with several “da’s.” She was coming round. The corridor in which we were talking was tiny and narrow. It connected three doors and a lift. The opposite of the ideal place to receive a confession. “A tea; would you like to come and join us for tea, in a tea room or a restaurant? It would be quieter and easier to talk.” A rookie’s tactlessness, a misunderstanding of Russian culture, Lana would tell me later, explaining my mistake. A man can’t invite a woman for a drink, even if she’s as old as his grandmother. A meeting in her office, yes, that was possible. Tomorrow? “Why not, tomorrow. If you like. But I don’t think it will be terribly interesting,” Dina simpered like a schoolgirl.

If the level of seniority of a state employee must be judged by the size of her office, then Dina could lay claim to the post of “toilet lady.” It was far from that of the head of the special collection of the big State Archives of the Russian Federation. What mistake could this woman have committed, to find herself in such a small and uncomfortable room? Low-ceilinged, with a window so narrow that a child would have had trouble getting its head through it, her office was so small that if more than three people had been in there they would hardly have been able to breathe. It was accessed directly by the stairs, which, on the other floors, normally lead to the toilets. Hence “toilet lady.” A thick silvery mane about ten centimetres long rocks back and forth above a formica table in front of us. Dina is sitting working in semi-darkness. Our arrival doesn’t disturb her activity. Her baroque hairdo resists the laws of gravity and remains powerfully attached to her skull. No stray strand comes away from the capillary mass. Is it a wig? Without even looking up, Dina addresses Lana. She reminds her how precious her time is. In return we assure her that we are perfectly aware of that, and we apologise for interrupting her very important work… Lana is never one to hold back. Dina listens to her not without displeasure [is this what is meant?] and then decides to look at us. “I’d forgotten about our meeting. As I told you yesterday, I don’t know if I can help you, and I still have lots of documents to file.” The transformation is striking. Moving. Dina is dressed up as if for a dance. Colour on her cheeks and on her lips. Pink, unless it’s mauve; at any rate, it’s very much apparent. No, Dina hasn’t forgotten about us. She was waiting for us. For the first time in ages, Lana and I relax. The conversation should go well.

The Viet Cong had won after two decades of war. In that year, 1975, the Communist doctrine triumphed and spread over all the continents. The Soviet Union carried more weight in the world than ever before, and treated the United States as an equal. In Moscow, food shortages had been a thing of the past for a long time, and political purges had become less frequent. The future for the Soviets seemed radiant at last. Leonid Brezhnev had been in charge of the country for eleven years. He had the jowly face of an apparatchik; not brilliant, perhaps, but less terrifying than Stalin. It was in this almost peaceful Soviet Union that Dina Nikolaevna Nokhotovich, at the age of thirty-five, saw her life collapsing from one day to the next. GARF has ceased to exist. The whole of the state administration (a perfect pleonasm, since in the Soviet Union the private sector didn’t exist) was identified in Soviet-compatible terms. The administration for which Dina worked didn’t escape this process, and was soberly entitled “Central State Archives of the October Revolution and the Edification of Socialism.” That was forty-one years ago. In a different era, in a different country, under a different regime.

Dina can’t help pursing her lips between each of her phrases. Her eyes are staring at an imaginary point that removes her from the present moment, from her tiny office at GARF and this neo-capitalist twenty-first-century Moscow. For a long time she says nothing. Then her story begins. “I had just been put in charge of the ‘secret’ department of the archives. That was in 1975. The post was like no other, because it dealt with the confidential documents of the history of our country, the Soviet Union. At that time, the state worked perfectly, and we weren’t short of qualified staff. Custom decreed that my predecessor came to give me the basic information, the information that was supposed to allow me to accomplish my mission as well as possible. Strangely, that never happened.” The former head of the secret department had simply disappeared. Gone, flown away, not a trace. As if he had never existed. And today, Dina can’t remember his name. What happened to him? A sudden transfer to another administration? An accident? A serious illness? Dina never knew and never asked. A Stalinist habit–some people might call it the survival instinct–reigned in this people’s “paradise.” In the Soviet Union, those who disappeared could hope for no help from those who stayed behind. Their memory was erased from the collective memory. In the mid-1970s, Dina didn’t feel like playing at being the heroine; her predecessor was nowhere to be found. Too bad. She would get by without him.

“I was impatient to discover what kinds of documents I was responsible for. I remember, when I went into my new office, I found several safes. Security gave me the keys and I was able to open them.” Even today, these huge safes, tall as sideboards, wide as fridges, stand in most of the rooms in GARF. What do they hide? All of our questions went unanswered. Perhaps they’re just empty. They would be too heavy to move. In 1975, Dina’s safes were really used. “There were documents inside, but also objects. The most surprising thing is that none of those objects had been inventoried. No code, no register, no classification. They quite simply didn’t exist.” A lot of people, in those days, would simply have put everything back in the safe and been particularly careful to forget their existence. Not Dina. “I was curious to know, I wasn’t afraid. Why would I have been afraid? I wasn’t doing anything forbidden. I asked a colleague to join me, and we both started going through this treasure trove. There were objects wrapped in cloth. Some were bigger than others. When I opened the smallest one, I’d have to say that we were quite frightened. It was a piece of human skull.”

The story is interrupted by a strange metallic click. The sound comes closer to Dina’s office. It’s Nikolai. He comes in, pushing a supermarket trolley. The same pale Nikolai Vladimirsev who had been so horrified about the manhandling of the skull. Now we just need the director of GARF and we’d have the full team. Dina isn’t surprised. She gets up and asks us to follow her. The rest of the conversation will take place in the room where we were able to study the skull six months before, on the ground floor of the building. Without taking the trouble to reply to our greetings, or even to apologise for interrupting our discussion, Nikolai follows us with his ridiculous little trolley. The clatter of the wheels on the tiles echoes down the sleepy corridors like some infernal machine. Reaching the room with the rectangular table, Dina takes a seat and asks us to do the same. Nikolai parks his trolley in a corner and takes out some battered files and a thick cotton sheet. The scene is played out in silence. Dina guides her colleague with a wave of the hand and shows him where to set it all down. Files at the end of the table, the worn sheet just in front of us. “There… Everything that I’ve found is here.” Just as Dina says this, her colleague unfolds the sheet with a wide and graceful gesture to reveal… some table legs. “Step forward. You’re allowed to do that.” Nikolai has regained the gift of speech, and seems almost chatty. “Here’s the other proof of Adolf Hitler’s certain death: traces of blood on the legs of his sofa.”

Parts of the sofa taken from the Führerbunker in Berlin in May 1946 (GARF)

Does Larisa Rogovaya, the director of GARF, know that we’re in here with these historical pieces of forensic evidence? Has she organised this little show? It would be amazing if not. Nothing can be decided without her agreement. Certainly not after the dubious episode with the American archaeologist. I don’t let Lana get in her phrase about the “human factor” again, and pick up the thread of our questions with our new best friends, Dina and Nikolai. “Apart from the skull, there were these bits of wood,” she confirms. “At first, when we took the boxes out of the safe, we had no idea what they could be. When we did some searching, we found a piece of paper. It said: ‘This is a piece of Adolf Hitler’s skull. It must be transferred to the State Archives.’ Without intending to, we had shed light on one of the biggest mysteries since 1945.”

The cult of secrecy, the endless care with which information was hidden away, and punishments for neglecting to obey these two rules: Dina’s professional life, over a long time, is simply summarised here. Of course the archivist wasn’t part of the KGB, but she still had to behave like a spy. Not out of pleasure, but out of obligation. The staff of the Soviet State Archives, depending on their seniority and level of accreditation, were all subject to the same paranoid surveillance by the authorities. Quite simply because they had access to the heart of the matrix of the regime: its deepest, darkest secrets. The Katyn massacre, those thousands of Polish officers executed in a Russian forest on Stalin’s orders during the Second World War, the little arrangements made with the leader of nationalist China, the right-winger Chiang Kai-shek, against Mao the Communist, or internecine battles within the Red Army. Whoever controls the archives can rewrite official history and, with a click of the fingers, destroy the legends that have shaped it. Why should we be surprised that, unlike many states, Russia continues to keep its past locked away? Today, the conditions for consulting the archives remain basic: on the one hand there are open documents, and on the other those that might damage the higher interests of the state. The latter fall under the category “sensitive,” and can only be consulted with express authorisation from the very highest levels of the regime. Which is to say, hardly ever. The problem with Russian documents is that they can all fall under the heading of “sensitive.”

Dina, with her simple post as an archivist, had to accept the life of a pariah without even the frisson of adventure. At least until the fall of the regime, late in 1991. “The USSR was a different time, with different rules,” she acknowledges with a pout. Is it a pout of disapproval or nostalgia? “In 1975 life wasn’t the way it is today. I’m talking about mentalities, material comforts, everything… We had instructions that had to be respected. And so many things were related to ‘defence secrets’…” One of the most important of those instructions was to be suspicious of everyone. Of your colleagues, your neighbours, your own family. And to report the smallest subversive action to your superiors. Finding Hitler’s skull hidden in a box at the back of a safe in the archives–was that subversive? Potentially yes.

After its discovery, there was no going back for Dina. She had to report it to her superiors. Very quickly, it appeared that nobody in her service had ever heard of this human fragment. “I think only my predecessor knew it was there. But since he had disappeared, I never got to the bottom of this affair.” Is that all? Dina finds Hitler’s skull and the story stops there? Wasn’t she rewarded? A promotion, a bigger apartment in a part of the city for deserving citizens? “None of any of that. The director of the archives asked me never to talk about it. You can’t understand, you’re both too young. You, Lana–you’re Russian, aren’t you? You’ve known the Soviet system?“ Lana has forgotten nothing. She often speaks emotionally about the USSR, the way one remembers distant childhood memories. Brezhnev had got fat and old and he was still in charge of the country when Lana was born. That was in 1978. Only a few years after Dina’s adventure. “The atmosphere was very special at that time,” the old archivist continued. “Very special. Any information like the business about the skull could end the life of someone who couldn’t hold their tongue. Hitler and his bones were still classified as ‘top secret.’ For all those years, I never broke my vow of silence.”

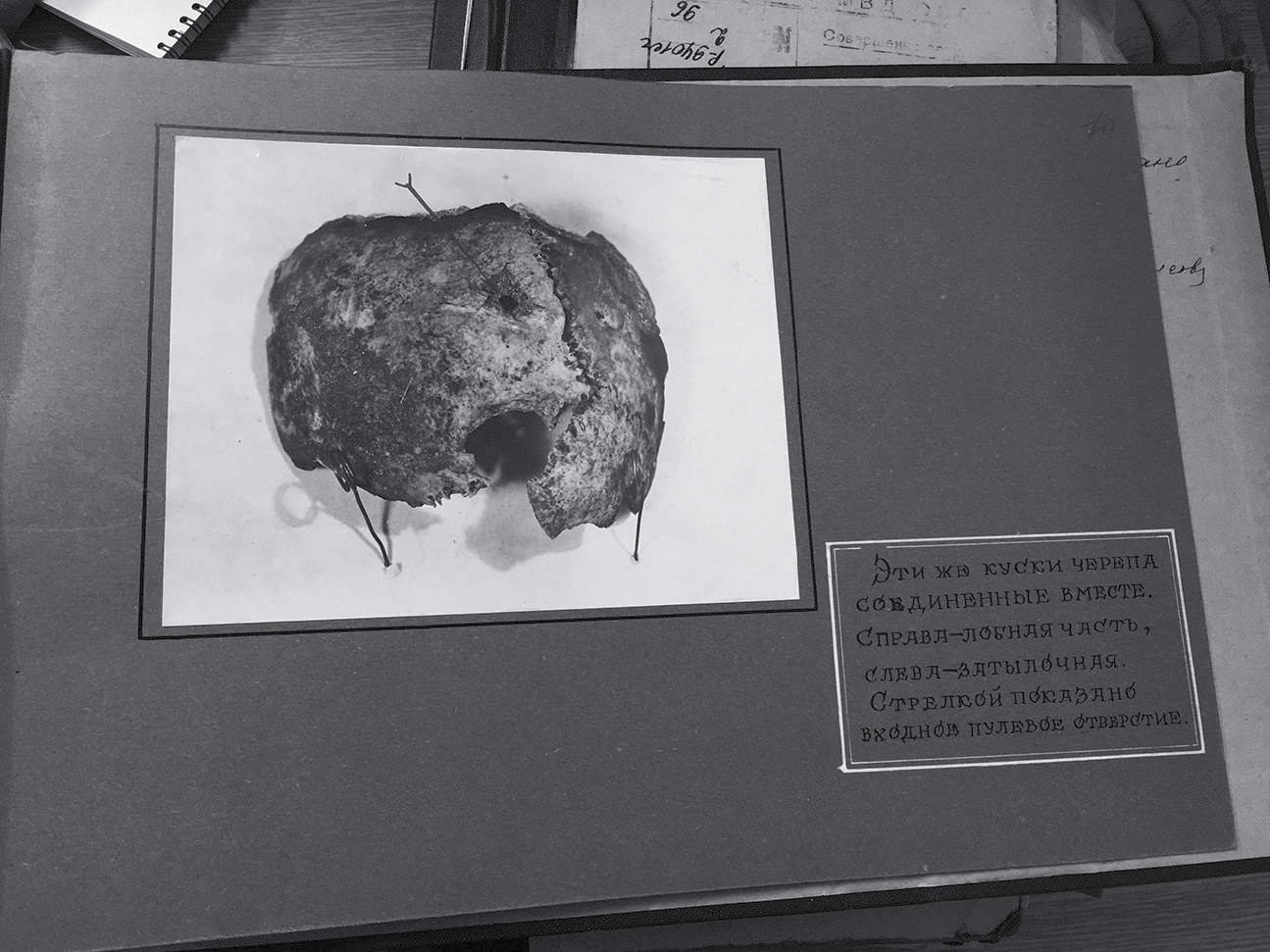

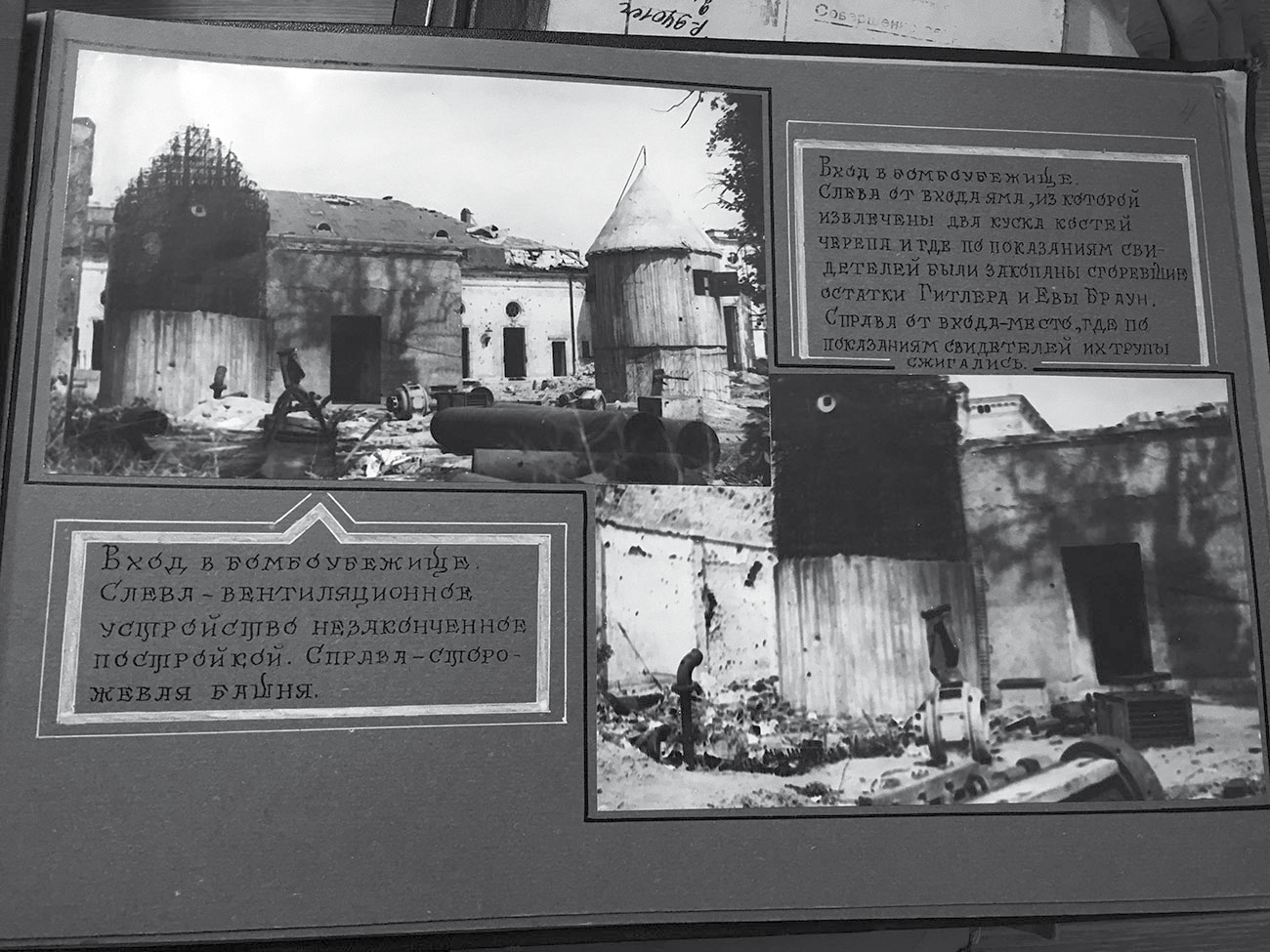

Nikolai has set down a photo album in front of us. He probably knows the ins and outs of his colleague’s history so much by heart that he doesn’t need to pay attention to it. The album contains a series of black-and-white photographs neatly glued in and surrounded by a frame drawn in black ink. Each of the photographs has a caption, long or short, handwritten with great care.

Photos of the New Reich Chancellery and entrance of the bunker taken in May 1946 (GARF)

Lana translates them for me. “Entrance of the New Reich Chancellery… Gardens of the Chancellery… Entrance of the bunker…” We are holding in our hands the photographic record of the investigation into the death of Hitler. It’s dated May 1946. It contains everything, the external views of the bunker, the inside too, and particularly the scene of the crime, or at least the suicide. But no body. The sofa on which Hitler was supposed to have died was photographed from every angle. Front, side, underneath–nothing is omitted. The back rests in particular held the attention of the investigators. And rightly, since the dark drips appear clearly on the right-hand side of the sofa. On the following page, there are more photographs of the back rests, but this time they have been removed from the rest of the sofa. The precise caption: “Pieces of the sofa with traces of blood. These pieces have been removed to be used as evidence.” Their shapes and sizes correspond feature for feature with the pieces of wood that Nikolai has brought us. “They’re the same,” Dina confirms. “The Soviet secret services removed them from the sofa to bring them to Moscow. They hoped to analyse these traces of blood and check that they were Hitler’s.” Nikolai picks up one of these pieces of wood and shows us the section of the back rest from which the Soviet scientists took their samples in May 1946. Obviously the archivist doesn’t wear sterile gloves. Does he know that he might be destroying any potential traces of DNA? He doesn’t understand when we point this out. What was the result of the samples taken in 1946? “It was blood type A,” Dina goes on. A very widespread blood group in the German population (almost 40 per cent), and more importantly one which, according to Nazi doctrine, proved membership of the “Aryan race.” Of course, it was Hitler’s blood group. The last few pages of the album linger on the skull. The one believed to be Hitler’s, the one we had been able to see for a few moments in that very room. In one of the photographs, an arrow drawn in red points to a hole in the skull.

The Soviet secret services suggest that it looks like the entry wound of a projectile. If the skull is indeed that of the Nazi dictator, it means that he received a bullet directly to the head. A sacriligious hypothesis in 1975. And very dangerous for Dina. Until the fall of the Soviet Union, Moscow wouldn’t let go. Hitler killed himself with poison, the weapon of cowards in the eyes of the Soviet rulers. This version, validated by Josef Stalin, failed to stand up if the skull with the bullet wound was made public.

Dina would have to live with that secret for decades. She wouldn’t be able to travel abroad, she would be under the surveillance of the authorities and wouldn’t be able to change jobs. As a result she spent forty years in the same service, wasting away amid dusty documents that no one could consult. “Our department was called the ‘Department of the Secret Collection,’” she goes on. “The only things kept here were confidential files. And there was no question of declassifying anything. None of the staff of this department were able to talk about anything they did. Even among ourselves, we didn’t talk about the documents of which we were in charge. There was no communication between one floor and another.”

Photo of the skull believed to be Hitler’s in a photo album at GARF.

The dashing septuagenarian pursues her mission just as diligently as always. Dina no longer really understands the new rules of her country. Declassified, reclassified–which documents are accessible? She’s a bit lost. “The last time I was able to speak openly about that skull was in the early 1990s. My superiors suddenly opened up all our doors to researchers. There were historians, and then, very quickly, journalists turned up. A lot of journalists. And that’s where everything got complicated.” An article published in the Russian daily Izvestia on 19 February 1993 marked the start of a crisis. “I’m holding in my hands the remains of Hitler’s skull,” the journalist Ella Maximova wrote. “They are preserved amidst conditions of the greatest secrecy in a cardboard box labelled ‘blue ink for fountain pen,’ along with some blood-stained fragments of a sofa that was in the bunker.” She was the first to reveal the scoop. The news was immediately picked up all over the world. For many years, there were rumours claiming that the KGB had not destroyed the Führer’s body, but had kept it hidden somewhere in Moscow.

And then a national newspaper confirmed that the legend was partly true. But wasn’t the skull a fake? Mightn’t it be one of those manipulations of which the Russians were so fond? Western historians immediately declared their fury. They stated categorically that all of this was impossible. Hitler’s skull? What nonsense. Meanwhile the foreign press got very excited. They wanted to see. In this Russia recently freed from its Communist trappings, money dictated the rules. Anything could be bought, anything could be sold, everything had a price. Including Hitler’s skull? Some people said yes. Tension mounted when the correspondent of the German magazine Der Spiegel said he had been offered access to the bones and five interrogation files from eyewitnesses of the last days of Hitler for a large sum of money. And not in roubles. The Russians had been too greedy, and Der Spiegel preferred to withdraw from the auction. “We wouldn’t have given half of what they were demanding,”* the magazine’s Moscow correspondent explained at the time.

“Those articles harmed us a lot,” Dina says. “The journalists… saying that we didn’t want to show the skull, that we were asking for money, that’s all false. It was in order to prove it that our authorities decided to organise a big exhibition about the end of the war and display Hitler’s final remains.” With the success that we know about. New scandals about the identification of the skull, and then the decision by the Russian authorities to put the object back in its safe and not let the journalists get anywhere near it. “Of course everyone wants to know if it is really Hitler.” Nikolai can’t conceal the faintly irritated expression that never leaves his face. “You want to study the skull, analyse it, why not? I know it’s his. I know how Hitler killed himself. I’ve read all the dossiers from the investigation. From 1945, when the inquiry began, it’s all there. But if you want to start again, go ahead.” Is that the answer, at last, to all our questions? Is this strange archivist conveying his director’s decision to us? “Can we carry out tests on the skull? Is that it?” Dina and Nikolai look at one another. They are both reluctant to speak. “Our task is to keep the archives in the best possible condition so that future generations can consult them. We don’t have to carry out scientific experiments.” Nikolai doesn’t give a clear answer. Lana points this out as politely as possible. He replies in the same monotonous, reedy voice. “None of these questions concerns us.” A smile. Hold that smile, even if it’s starting to look a little tense. Given her age and her long history in this post, it’s Dina we should be concentrating on if we want to get that important reply. “I imagine that’s possible, yes,” she says at last. When? How? Through whom? So many parameters to be determined, so many points to be illuminated. We can come back very quickly with an important specialist. We’ve chosen him. He knows all about it. “His name?” Nikolai asks. “You know him, we’ve told you all about him in our emails. His name is Philippe Charlier. A Frenchman. He is a qualified medical examiner. Very well known in France. You must know him. The identification of the skull of Henry IV: that was him.”

We’ve made an agreement. Lana talks to the two archivists to confirm once and for all what they have just told us. In the meantime I avidly consult the files that Nikolai has taken the trouble to bring with him. They are the reports by the Soviet secret services into the disappearance of Hitler. Unusually, I am given permission to take photographs of them. “All of them?” I ask. Nikolai says yes. I don’t hold back. I take pictures of everything. Dina looks at me out of the corner of her eye. I can see that she’s uneasy. She’s not happy about a foreigner freely taking pictures of her precious documents. She hovers around me, murmuring a few words in Russian. I don’t understand a word and that suits me fine.

She goes on repeating the same words. I go on. All of a sudden she loses her temper and calls Lana, who is still talking to Nikolai. She talks agitatedly to my colleague, pointing at me with her finger. Lana turns towards me, slightly panic-stricken: “You’ve got to stop. You’re only allowed to take ten photographs. No more than that!” I pretend not to hear her and go on. Now Dina is really shouting at Lana. Why ten? I try to gain some time and pretend to be surprised. Nikolai said I could take as many as I liked. “That’s just how it is,” Lana replies. “She thinks ten is enough.” How can I be cross with dear Dina? She has spent her whole professional life guarding these secret documents. Forty years protecting them from prying eyes, and you can’t just delete something like that. I imagine the shock she must feel seeing me, a Frenchman, a capitalist, pillaging the treasure trove of her professional life right in front of her eyes. She reacted too late; I’ve finished. I’ve got photographs of everything. The Hitler files are now in the memory of my smartphone. Several hundred pages to translate and digest. A painstaking job.

* The Independent, 20 February 1993, Helen Womack.