PARIS, OCTOBER–NOVEMBER 2016

The first translations of the documents photographed in the offices of GARF came in quite quickly. Lana has worked wonders. She prefers to send them to me in the evening, after her day’s work. Apart from this investigation into Hitler, she is still freelancing for the Russian media. For my part, I’ve gone back to France. I’m classifying the translated texts by subject and date. Some remain quite obscure. So many unknown names and obscure acronyms clogging up the administrative phrases. The Russian investigators hadn’t much time for poetry. Their work was dictated by efficiency and precision. Here’s one of the first documents I’ve been given:

Top Secret

To Comrade Stalin

To Comrade Molotov

On 16 June 1945, the NKVD of the USSR, under Number 702/b, presented to you and Comrade Stalin the copies received from Berlin via Comrade Serov of the records of the interrogations of certain members of the entourage of Hitler and Goebbels concerning the last days of Hitler and Goebbels’ time in Berlin as well as copies of the description and the files of the medico-legal examination of what are presumed to be the corpses of Hitler and Goebbels and their wives.

Nothing’s missing: not the big historic names of Stalin, Hitler, and Goebbels, nor the abbreviations NKVD and USSR. And this was only the beginning. Other names and other equally resonant abbreviations would haunt Lana and me during the months of this investigation like so many ghosts emerging from an accursed past. On the German side: Himmler, the SS, Göring, the Third Reich… On the Soviet side: Beria, Molotov, the Red Army, Zhukov…

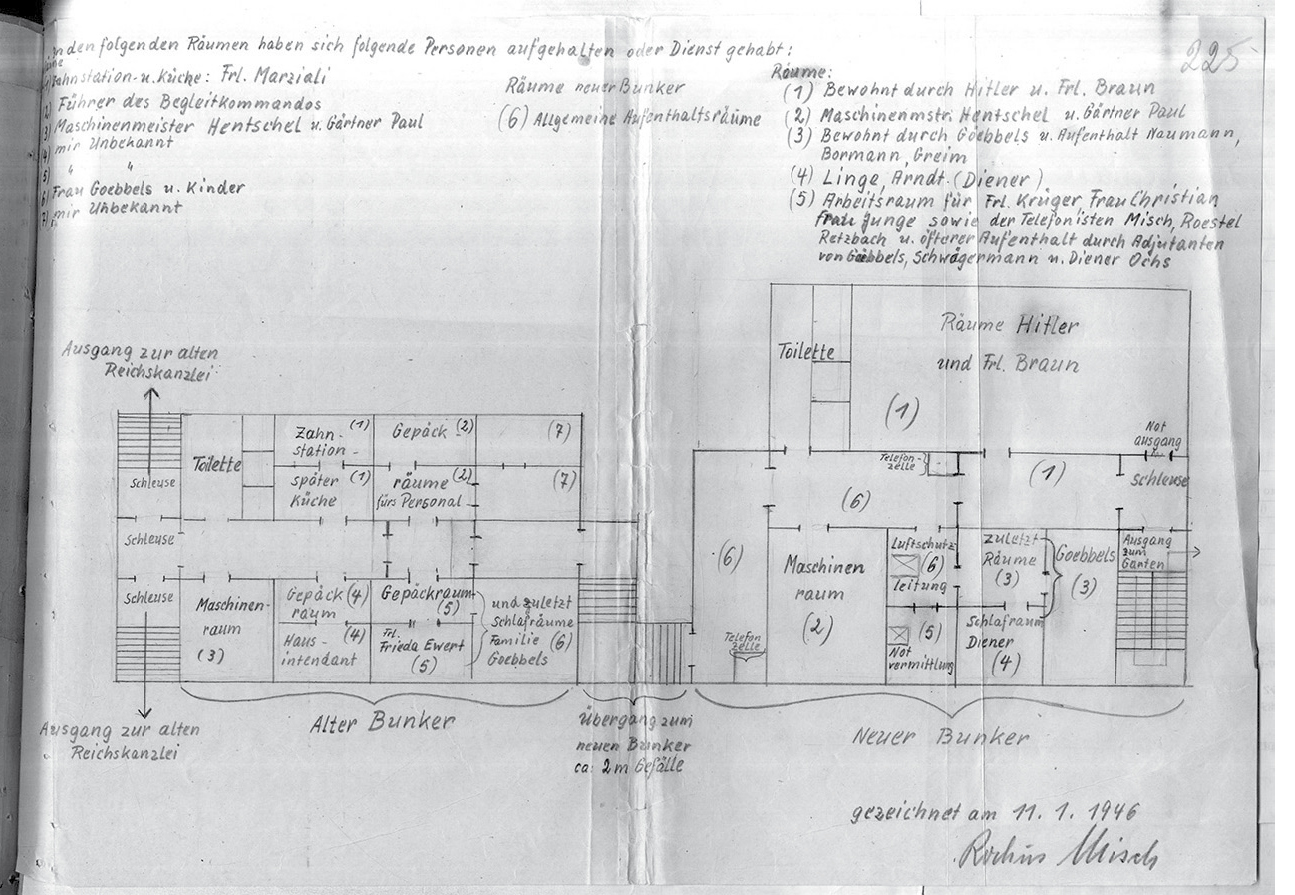

As well as these reports, we have collected a series of captioned photographs and some drawings, including diagrams of Hitler’s bunker. They are drawn in pencil on paper by prisoners, SS men, all members of the Führer’s inner circle. They had been ordered to draw them by the Russian special services. The aim was to understand how life was organised in their enemy’s air-raid shelter. Everything is precisely annotated: the apartments of the Nazi dictator, Eva Braun’s bedroom, her bathroom, the conference room, the toilets…

Diagrams of the Führerbunker (GARF)

The mass of documents in the GARF collection includes several dozen pages in German. Some interrogations of Nazi prisoners have been transcribed directly in their language and by hand as most of the Red Army typewriters used Cyrillic characters. Luckily, the handwriting of the Soviet interpreters is still quite legible. Except in one particular case, in which the letters look like the scrawls of a spider, not to mention the many crossings-out. These barely decipherable texts wore out the eyes of two of my German-French translators. The first ended up throwing in the towel. As for the second, he asked me not to rely on him in the future if the situation came up again. Their determination was not in vain: thanks to them, I was able to place this document within the great historical puzzle formed by the Russian archives of the Hitler file. These spidery squiggles record the interrogation of a man by the name of Erich Rings, one of the radiographers in Hitler’s bunker. In particular, Rings gives an account of the moment when his superiors asked him to pass on a message about the Führer’s death: “The last telegram of this kind that we have communicated dates from 30 April, at around 5:15 pm in the afternoon. The officer who brought the message told me, so that we would also be informed immediately, that the first phrase of the message was as follows: ‘Führer deceased!’”

If Rings is telling the truth, this information implies that the German dictator’s death occurred before 5:15 pm on 30 April 1945. But might the Nazi radiographer have been lying to the Soviet investigators? They assume that he might. Suspicion is the essence of any good spy. It is a great asset in all circumstances, and allows them to climb through the ranks of their hierarchy with confidence. Suspecting the enemy, his declarations, including those made under torture. Still, this systematic attitude does obstruct the progress of the inquiry. And my own work, too. The texts that I have in front of me concern a period of almost twelve month, leading up to the middle of 1946. So, almost six months after the fall of Berlin on 2 May 1945, the officers in charge of the Hitler file still hadn’t completed their investigation. They asked the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs to grant an additional delay. As well as the transfer of certain German prisoners from Russian prisons to Berlin. The aim was to reconstruct Hitler’s last hours.

To the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, Comrade S.N. Kruglov.

Within the context of the investigation into the circumstances of the disappearance of Hitler on 30 April 1945, the following are currently held in Butyrka Prison [in Moscow]:…

This is followed by a long list of Nazi prisoners; then the document resumes:

In the course of the investigations into these individuals, apart from the contradictions causing doubts about the plausibility of the version of Hitler’s suicide already given to us, certain additional facts have been revealed, which must be examined on the spot.

In this respect, we think that the following arrangements should be put in place:

All individuals arrested in this case must be sent to Berlin.

[…]

Give the task force the job of investigating, within a month, all the circumstances of the disappearance of Hitler and to deliver a report on the subject to the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR.

Give Lieutenant General Bochkov the task of organising the accompaniment of prisoners under escort, and to allocate to that end a special wagon for the inmates to the city of Brest [in present-day Belarus]. The accompaniment of the prisoners under escort from Brest to Berlin will be undertaken by the Berlin task force.

For the study of pieces of evidence and the scene of the incident, send to Berlin the qualified criminal investigator of the General Directorate of the Militia of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR, General Ossipov.

The letter is signed by two Soviet generals based in Berlin.

April 1946. Why did the investigation into Hitler take so long? What happened in the bunker? The Russians devoted such energy to investigating that truth that escaped them. And yes, more than any other Allied army (the Americans, the British and the French), Soviet troops had taken hundreds of eyewitnesses of the fall of Berlin and the Führer prisoner. Witnesses who were put severely to the test by their jailers. I can see that determination to solve this mystery just below the surface of many of the reports and interrogations. The same questions keep returning, the same threats. Why not simply accept the evidence? Why can’t Stalin and his men admit that the prisoners are telling the truth? I would have made a very bad member of the Soviet secret police. The proof lies in this confrontation between two SS prisoners who were close to Hitler.

The first is called Höfbeck and is a sergeant, the other is called Günsche and is an SS officer.

Question to Höfbeck: Where were you and what did you do on 30 April 1945? The day when, according to your statement, Hitler took his life?

Höfbeck’s reply: On 30 April 1945 I was posted to the emergency exit of the bunker by my departmental head, State Councillor [Regierungsrat Högl, head of a group of nine men].

Question to Höfbeck: What did you see there?

Höfbeck’s reply: At 2:00 pm, or perhaps a little later, as I approached, I saw several people […]. They were carrying something heavy wrapped in a blanket. I immediately thought that Adolf Hitler must have committed suicide, because I could see a black pair of trousers and black shoes hanging out on one side of the blanket. […] Then Günsche shouted: “Everyone out! They’re staying here!” I can’t say for definite that it was Günsche who was carrying the second body. The three other comrades immediately ran off, I stayed near the door. I saw two bodies between one and two metres from the emergency exit. Of one body, I was able to see the black trousers and the black shoes, of the other (the one on the right) the blue dress, the brown socks and shoes, but I can’t say with any certainty. […] Günsche sprinkled petrol over the bodies, and someone brought him a light near the emergency exit. The farewells didn’t take long, five to ten minutes at most, because then there was some very heavy artillery fire. […]

Question to Günsche: What can you say about Höfbeck’s witness statement?

Günsche’s reply: It wasn’t at about 2:00 pm, but shortly after 4:00 pm that the bodies left the bunker by the emergency exit. […] I didn’t help to carry Adolf Hitler’s body, but a little while later I passed through the emergency exit with Frau Hitler’s body. Adolf Hitler’s body was carried by people I’ve already mentioned in previous interrogations. […]

Question to Höfbeck: Do you have any objections about Günsche’s testimony that you have just heard?

Höfbeck’s reply: I have no objection to Günsche’s testimony that I have just heard. […] I have to say that my previous statement may contain some inaccuracies, given that these unexpected events have unsettled me very much.

The inaccuracies in the witness statements drive the investigators mad. Are the prisoners doing it on purpose? There are strong reasons for thinking they are. Let us not forget that for the Nazis, the Communists embody absolute evil (according to Hitler’s doctrine, just after the Jews). Resisting, lying, or distorting reality may seem natural to men inspired by Nazi fanaticism that is still very much alive. Be that as it may, their contradictory answers complicate the precise establishment of the events that preceded the fall of Hitler’s bunker.

Lana and I thought we were sufficiently prepared for this plunge into one of the last mysteries of the Second World War. Big mistake. Even in our most pessimistic scenarios, we couldn’t have imagined the level of complexity of an investigation such as this. We would soon discover that the collection of documents in the GARF stores wouldn’t be the hardest part. Our confidence and optimism were quickly dampened. It was Dina, the head of GARF’s special collection, who alerted us.

Let’s return to our meeting during autumn break 2016 within the walls of the Russian State Archives. Lana and I were busy thanking Dina and Nikolai for their patience. They had already filled the shopping trolley with the pieces of wood from the sofa and the files about Hitler. The interview ended cordially. “We succeeded, we have all the documents about the disappearance of the Führer, it’s a first!” Lana was getting carried away and I let her. Dina didn’t share her enthusiasm. Nikolai had already left without saying a word. We could hear him pulling his trolley along the corridors with the same delightful racket as before. “You haven’t got everything,” Dina suddenly announced, almost sorry to spoil our pleasure. Not everything? “There are still bits of Hitler elsewhere in Russia?” I asked without really believing it myself. “It’s possible…” Dina had trouble answering frankly. “In fact, yes,” she acknowledged at last. “But you won’t be able to see them.” Our house of cards was collapsing. Still biting her lips and avoiding our eyes, Dina felt uneasy. Lana started talking to her as gently as possible to reassure her. To tell her that it wasn’t very serious, but she had to explain everything.

Good news and bad news. Where did I want to start? Lana let me choose. We had left the GARF offices and caught a taxi to get back to our hotel. Let’s start with the bad news. “Not all the Soviet reports on Hitler’s death are kept at GARF. Some of them are stored in the archives of the FSB.” Silence… Was there more bad news? Not for certain. The three initials mean “Federalnaya Sluzhba Bezopasnosti” (Federal Security Service), the Russian secret service. The FSB was set up in 1995. In a way, this was the successor to the KGB, which had been dissolved on 11 October 1991, following an attempted coup d’état against Mikhail Gorbachev in August 1991. The FSB’s methods haven’t fundamentally changed from those of its illustrious elder sibling. Methods based on manipulation and, if necessary, violence. If access to GARF had seemed difficult, how hard would it be to get into the archives of the FSB (the TsA FSB, short for Tsentral’ny Arkhiv FSB)? Lana was almost laughing, our quest had taken such a desperate turn. “There’s something else you need to know,” she continued with a nervous hiccough. “Dina also told me that we would certainly have to dig in the military archives. On the other hand, she was very clear, we can’t expect any help from GARF. The FSB, the military archives, and GARF all hate each other. We’re going to have to manage on our own.”

The taximeter was ticking off the roubles that our route was going to cost. It all seemed so easy for the driver. Two customers, an address, a good GPS, and he was all set. The exact opposite of our investigation. “You don’t want to know the good news? The positive thing that Dina wanted to tell us?” Lana sensed that I was growing weary. Over a year of Sisyphean research was beginning to dent my enthusiasm. “Dina assured me that she liked us, and that she’d support us in our bid to carry out scientific examinations on the skull.” Did Dina have the slightest power over the examination of the skull? Lana started thinking, and then shook her head. Moscow was playing with us, with its fine drizzle. Other people had tried to investigate Hitler. If they’d all failed, was it a coincidence?

A fierce and almost desperate combat? Perfect! Lana doesn’t give up, quite the contrary. She promised me she would obtain all the permissions before the end of the year, the ones that we needed to access the FSB archives and those opening the doors of the Russian State Military Archives (RGVA). “No one resists me for long. I will wear them down,” she assured me with her swaggering air in the departure hall of Sheremetyevo Airport in Moscow. That was less than a month ago. Since then, not a day goes by when I don’t talk to her on the telephone, when we don’t give each other encouragement. I’ve been working on the documents, she’s been working on the Russian authorities. “I’m nearly there, another few days and I’ll have my answer. Stay alert, we’re going to need to react quickly.” Lana doesn’t let go, and she can’t imagine a second failure. Are her connections with Russian power really so solid? How would she convince administrations that were usually so impervious to this kind of request? “Since my work on Svetlana Stalin, I can count on good relations with people of influence, and they know me, they know I’m like a pit bull. I never let go of my prey. And believe me, dictators know me…”