MOSCOW, MARCH 2017

We have only two days. That’s all the Russian authorities have granted us. Two days to carry out a forensic examination. We had to fight to get even this. “Haven’t you ever thought of carrying out scientific tests on Hitler’s human remains? Or rather the remains that are potentially those of Hitler?” Alexander Orlov, our contact at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, didn’t expect these questions. It was last December. He got in touch with us again just to know how we had got on with the FSB archives. He’d hoped he was done with us. The teeth, the skull and confidential files, wasn’t that enough? “We want to know once and for all, without the slightest doubt…” He’s heard these arguments so often, from so many journalists, historians, even scientists. Tests, new technology, with no damage done to the skull or the teeth. Alexander speaks good French. But when he finds himself in a stressful situation, he prefers to reply in his mother tongue, Russian. Lana resumes the conversation. Alexander resists. He claims he doesn’t know.

We have only one goal, dear Alexander, which is to put an end to the legends, the rumours of a possible escape by Hitler. Didn’t Russia want to know whether it had Hitler’s human remains? Unless you’re afraid you were wrong for so long? There’s only one way to bring this chapter to an end once and for all: let the forensic examiner, Philippe Charlier, come and examine the skull and the teeth.

Silence. Then his voice darkened all of a sudden: “I’ve got it. I’ll give you an answer soon…”

Our reply came in early March. It was: “Two days! One day per archive. Come at the end of the month.”

That worked out perfectly. We had also just got the green light for the military archives. We’d be able to kill two birds with one stone.

Dr. Philippe Charlier would be joining us for those important two days. The French forensic examiner and archaeo-anthropologist was the obvious choice for us. In just a few years, this scientist had built up a solid reputation for penetrating historical mysteries. The most famous “murderers” in history speak beneath his skilful fingers. Poison, blade, pistol, nothing escapes him. His accomplishments impress his peers, but also the wider public all over the world. The kings whose remains have passed through his hands include France’s Henry IV, Saint Louis, Richard the Lionheart, and legendary figures like Joan of Arc, and the tribune of the French Revolution, the terrible Robespierre. Philippe Charlier liked to publish the studies of his “patients” in the world’s finest scientific journals. A youthful man in his forties, enthusiastic, an adventurer (he loved to travel to the remotest spots on the planet to practise his skill), he combined popularisation with a scrupulous respect for classical scientific principles. Hardly surprising that the media saw him as an “Indiana Jones of the graveyards,” and passed on in detail each of his new historical autopsies. No way would he be willing to miss the Hitler file.

Two days, then. One day for the skull in the GARF Archives and one more for the teeth in the company of the shady spies of the FSB. GARF and the TsA FSB dragged their feet as they usually did, and talked terms. They all reacted in the same way: “Our country is drowning in forensic specialists. We don’t need a foreigner.” And they were perfectly right. A Russian would carry out the tests just as seriously, we had no doubt of that. And yet, out of concern for neutrality, as far as we were concerned what was needed was the opinion of a foreign scientist. To our greater surprise, the argument was accepted quite quickly. To avoid any suspicion or pressure from the Russians, we were given permission for the French doctor of our choice to intervene. We just had to find the dates that would satisfy everyone. Those would be 29 and 30 March.

Moscow, 28 March. I have twenty-four hours to check that everything will be ready for Dr. Charlier’s arrival. The Russian capital is calmer than usual. The walls of the Kremlin no longer hum with the babbling of groups of tourists. Lenin’s tomb is empty of the devotees of the Communist mummy. In the square are dozens of police officers, truncheons visible, regulation grey fur hats decorated with the insignia of the forces of law and order. They have the closed faces of people who have been given strict instructions. Two hours earlier, a demonstration of opponents of the regime met in the city centre. An insult to Putin. The state powers didn’t hold back, and arrested seven hundred demonstrators. The pictures were shown on the news channels all around the world. Russia was going through a major economic and political crisis unprecedented over the past ten years. The country is getting tougher and turning in on itself. Not the optimum conditions in which to investigate the Hitler file. At best, the authorities have neither the time nor the energy to answer our questions; at worst, they see us as a new source of problems. I was barely surprised when I saw Lana in the café where we used to work. Her features were drawn and her gaze uneasy. She didn’t have to open her mouth. I understood. They’d just cancelled! Not all of them. Just the TsA FSB. Without giving a reason or justifying themselves. That left us with GARF, the state archives with their bit of skull. They hadn’t changed their minds. Not yet.

The people in charge of GARF have stopped replying. We’ve been waiting in the entrance hall for an hour. It’s 3:00 pm on 29 March, and Philippe Charlier’s plane has just landed at the international airport of Sheremetyevo, an hour away from the centre of Moscow. Yesterday, Alexander Orlov had personally intervened on behalf of Lana. FSB cancelled, “date doesn’t work,” but not GARF. “Come on, they’re waiting for you.” Had they really said that? I ask Lana the question one more time. She sighs: “He said exactly those words.” So, the people in charge of the state archives know that we’re here, and that a French expert has come specially from Paris to examine the bit of skull, the one they keep in a miserable little computer-disk box! So why is no one replying to us? Even our passes aren’t ready. We confirmed a meeting about the skull with Dr. Charlier. The teeth would be later, another time. “When?” he had worried, rightly. Soon. We were using the same methods as the Russian authorities: vagueness and hope. Philippe Charlier reassured us immediately. “Don’t worry, I’ll find a window when the time comes, don’t you worry about that. I’m really interested in the project; you can count on me. But we’re okay about the skull?” In principle, yes. But we’re seething with rage in an empty waiting room. Do they even know that we’re here? Are they playing with our nerves for fun? Or is it just an illustration of the atavistic incompetence of the post-Soviet bureaucracy?

A woman in her sixties is sitting behind the only counter in the room. She’s the one who issues the passes. An oh-so important job that gives her the perverse opportunity to be as rude as she wishes, without the visitors to GARF daring to fight back. Right now she is eating a kebab and reading a glossy magazine without paying us the slightest attention. “They’re going to phone and tell her to prepare our documents,” Lana guesses, trying to remain optimistic. “It’s only a matter of minutes.” Nikolai Vladimirsev, the archivist with the waxy complexion, finally decides to come and save us. He has brought out the passes. The lady finished her sandwich long ago, and has started reading another magazine. She doesn’t even look up when we leave. Stay calm and polite, it’s all only a test. It doesn’t matter, because the skull awaits our forensic examination. Philippe Charlier should be joining us in about half an hour. We just have time to check that everything has been put in place. “The skull isn’t ready?” I can’t believe what Nikolai has just told us. And yet he confirms as much with his usual nonchalance. Nothing has been prepared. His opal eyes have never looked as bright as they do right now. “We will wait for Dr. Charlier before we put everything in place,” he goes on as we cross the courtyard of GARF towards the head office. “Nothing will begin before he gets here. And for your information, everything must be finished before the offices close at 5:30.”

Here we are again in this room where we were shown the skull last year. Only the decorations on the walls have changed. Instead of the revolutionary posters from 1917, a series of black-and-white photographs of the imperial family, the family of Nicholas II, the last tsar of Mother Russia. Should we see this as a desire on the part of the Russian regime to bring back the country’s imperialist past? I don’t dare to elaborate on this ideological choice in the company of Nikolai, and even less of Dina Nokhotovich, who has just joined us. The head of the department of the secret collection clearly didn’t expect to see us again. As usual, her manners are dictated by her mood. It’s late afternoon, and Dina seems irritable and doesn’t respond to our greetings. I recognise the big shoe box that holds the bones attributed to Hitler. It protrudes slightly from the little supermarket trolley that Nikolai never takes his eyes off. The trolley has been placed carefully at the end of the table. The same big wooden table. “Is there any chance of opening the box?” Lana translates my request. Neither of the two archivists replies. As if they can’t hear her, or no longer understand Russian. At last Nikolai reacts. Without a word, he sits down beside his little trolley, folds his arms defiantly and looks us up and down. The atmosphere of our meeting is becoming awkward. The silence is heavy. Lana breaks it. “Isn’t Larisa, your director, going to join us?” Anxious now, we even find ourselves wishing she was there. Clearly Dina and Nikolai aren’t keen on our forensic project. We need to know if this is merely a case of insubordination, two clerks uneasy with the idea of some strangers manhandling their “treasure.” Or, more generally, if the directors of GARF have found their own way of obstructing our work.

Philippe Charlier has just called us. He’s at reception, opposite the woman with the newspaper. She clearly doesn’t want to let him in. Nikolai agrees to move. Very slowly, he adjusts his hat on his sparse, straw-coloured hair, slips on his coat and comes with me. Imperturbably he greets the French expert with a frosty “ztrastvuyte” (hello). I tell Dr. Charlier about the complexity of the situation. I do so discreetly, because French is a language that many Russians understand, having learned it at school. In the Soviet era, French often replaced English as a compulsory foreign language. And Nikolai is easily old enough to have been a schoolboy under the hammer and sickle. “I understand, I’ll adapt,” the doctor murmurs. “I’m used to it.” Some positive vibes at last. Philippe Charlier has plenty of those. He adds, entering the room where Lana and Dina are waiting for us: “I’m going to have access to the skull. And that in itself is extraordinary.”

We think we know why our contacts are being so frosty. A big thank you to Professor Nicholas (known as Nick) Bellantoni of Connecticut University. That American professor of archaeology examined the skull in 2009 and declared that it belonged to a young woman! As we were given to understand at our first meeting with GARF staff last year, his little adventure traumatised Dina and Nikolai. Since that scandal, no scientist has been allowed anywhere near the human fragments. Philippe Charlier is the first. And he is kept under close attention. Nikolai stands a few centimetres away from him, ready to intervene if necessary.

First stage: observation. The French forensic expert picks up the diskette box holding the bit of skull. He brings it to his face and examines it from every possible angle. Nikolai opens his mouth and holds his hands out in front of him as if in a reflex. He is outraged. Normally he is the only one allowed to touch this little box. Dina pulls a face to express her own disapproval. Philippe Charlier is oblivious. All of his attention is focused on the bones. His confident attitude disconcerts the Russian archivists, who don’t dare to oppose him. For now…

“The first important thing you need to know is that it’s impossible to determine the sex of this skull just with a visual analysis.” The scientist speaks without hesitation. He goes on: “Does it belong to a man or a woman? No one can say with any certainty. It seems to me risky at best to make a diagnosis on such tiny fragments of bone. We have only the back left-hand part of the skull at our disposal. That part never gives a clue about its sex. I’m categorical on the matter.” In just a few minutes, Philippe Charlier has demolished part of his American colleague’s theory. Bellantoni claimed that the structure of the bones, too fine, too fragile, did not correspond to those of an adult male. “Wrong!” The Frenchman has no doubt. “On a skeleton, the diagnosis of sex is performed only on the pelvis. It’s unthinkable with a skull, a mandible, or a femur. And you would need to have the whole skull. Which is not really the case here.” And the age? Bellantoni reached the conclusion that the skull was that of someone aged between twenty and forty. But Hitler was fifty-six. How did the American get there? “He must have based his theory on the degree of closure of the sutures at the level of the skull.” Quite correct. In many interviews, the archaeologist from Connecticut makes no secret of his reasoning. It is based on the sutures that hold the plates of the skull together. This is what Nick Bellantoni says in a video shot by his university in Connecticut “Normally, as you age, they close down […], and these are wide open. An individual, I would have expected, twenty to forty years old.”* Philippe Charlier is able to study the sutures in question very closely. “I wouldn’t risk giving an age to a bone like this based only on the gap in the sutures. They vary so much between one individual and another. It’s possible that my sutures are completely closed like those of an old person, while my grandmother’s were open when she died. I insist, you can’t give the age of this skull on the basis of the sutures. Particularly when you only have a third of the whole of the skull. It doesn’t hold up.”

“Niet!” Dina isn’t happy. “Niet!” Nikolai agrees. Lana argues: we’ve got permission. “Niettt!” Dr. Charlier was about to put his sterile gloves on. He wanted them to open the diskette box for him so that he could take out the piece of skull. Lana had translated the question with a certain restlessness. The reply from the two archivists was as cold as a Siberian winter. We’re not opening it. Certainly not for a foreign scientist or some journalists. Dina says it again, on the brink of rudeness. Negotiation is no longer an option. The temperature in the room is starting to rise. Philippe Charlier intervenes calmly: “It doesn’t matter. We’ll do it without. Can I go on observing the skull anyway?” Nikolai didn’t expect such a calm reaction. The scientist turns towards him. He is a good head taller. “Just look, I won’t touch.” Dina finally says, “Da.”

“Then I will continue my observations. I will take my time, and too bad if they hoped to go home early this evening.” Lana takes advantage of the moment to escape into the corridor and call Alexander Orlov for help. After ten rings he finally picks up. The situation, the refusal, the obstacles erected by the archivists, Lana lets her distress spill out. Alexander is getting weary. He replies that there’s no longer anything he can do for us. “Sort yourselves out!”

It’s nearly six o’clock. Nikolai consults his watch. He taps his foot impatiently. The French expert feels the tension mounting around him. Unflappable, he taps all the information he has managed to glean into his computer. It will help him to write his report. Ultra-high-definition photographs of the skull and all the objects on the table will complete his work and allow him to verify his forensic examination. “Vascular orifice (right-hand unilateral parietal foramen), star-shaped loss of substance on the left parietal…” When he is working, the expert on the dead has no interest in the living people around him. Not even the crafty Russian archivists. “Look at this, for example, it’s very interesting…” He points at an orifice perfectly visible on the top of the skull. “This is clearly a bullet wound. The projectile passed through the head from side to side and emerged at the level of the parietal bone. This is an exit wound, not an entry wound. Its shape is typical, splayed towards the outside. It is about 6 millimetres wide. That isn’t to say that the calibre of the ammunition was 6 mm. I can’t establish a diagnosis of the calibre on the basis of an exit wound. The bullet could easily have fragmented or been deformed.” On the other hand, what seems certain in his eyes is the moment when the bullet went off. “It was fired at a cool, damp bone,” he confirms. If it is Hitler’s skull, the bullet was fired either while he was alive, or shortly after his death.

The investigation is proceeding at a crazy pace. Now the forensic expert’s attention is drawn by blackish traces on the skull. “These are residues of the burial medium, definitely soil. You can also see traces of carbonisation. They prove that it has undergone prolonged thermal exposure. This person was burnt at a very high temperature.” According to the survivors of the bunker, almost two hundred litres of petrol were used. “That’s perfectly consistent,” Charlier says. “Burning a body is very difficult. To make a human corpse disappear completely, it would take at least 100 kilos of wood or several hundred litres of petrol. A body is full of moisture. Hence, in many cases, the heterogeneity of the carbonisation.”

Nikolai listens as if he understands every word uttered in French. He almost relaxes. A hint of admiration appears in his eyes. Behind him, the whole of the Hitler file has stayed in the caddy. I can’t help consulting those dusty old documents again. I can easily decipher the signatures of the Soviet rulers of the time. Names that have become familiar to me from having studied them so much: Beria, “Stalin’s no. 1 cop,” Molotov the diplomat, Abakumov the ambitious spy… I’m looking for one passage in particular. The one concerning an interrogation of Heinz Linge, Hitler’s valet. The report dates from 27 February 1946. It’s typed and signed by the Nazi prisoner at the bottom of each page. I show it to Philippe Charlier.

Question: Tell us about the events that took place on 30 April 1945 in the bunker of the former Reich Chancellery.

Answer: At about 4:00 pm, when I was in the room outside Hitler’s antechamber, I heard a shot from a revolver and smelt gunpowder. I called Bormann, who was in the next room. Together we went into the room and saw the following scene: facing us, Hitler was lying on the sofa on the left, one hand dangling. On his right temple there was a large wound caused by a shot from a revolver. […] On the floor, near the sofa, we saw two revolvers belonging to Hitler: one a Walther calibre 7.65 and the other a 6.35. On the right, on the sofa, Eva Braun was sitting with her legs bent. She had no trace of bullet wounds on her face or her body. Both Hitler and his wife were dead.

Question: Do you remember clearly enough that Hitler had a bullet wound in his right temple?

Answer: Yes, I remember clearly. He had a bullet wound in his right temple.

Question: What size was this wound to the temple?

Answer: The orifice of the entry wound was the size of a three-mark piece [Linge would say in other reports: “a wound the size of a pfennig piece,” author’s note].

Question: What size was the exit wound?

Answer: I did not see an exit wound. But I remember that Hitler’s skull was not deformed, and that it remained complete.

The description of the wound broadly corresponds to the visual examination carried out by Charlier. If at this stage it remains impossible to determine the identity of the skull, the evidence agrees. Even better, the valet’s witness statement sheds new light on the matter for the forensic examiner. Notably the fact that the skull remained intact in spite of the shot. “If he really fired into his right temple, the exit of the bullet through the left parietal seems logical. And we have a way of knowing whether Linge lied or not. We can in fact check the hypothesis of a shot fired in the mouth.” What? “Thanks to the teeth! If we find traces of powder on the teeth or the gums, it’s a good argument in favour of an intrabuccal shot having been fired.” Those famous teeth which are in the archives of the FSB, and to which access has, for the time being, been delayed.

Dina has had enough, she wants to leave. It’s 6:30 pm; we’ve overshot closing time at GARF by half an hour! “Can we come back tomorrow? And continue with the analysis of the skull as well as the pieces of sofa?” Lana shouldn’t have spoken. Her question irritates the old archivist. “No! You have no authorisation for tomorrow. Finish for today. I will leave you for another few minutes.”

Philippe Charlier doesn’t understand a word of Russian, and hasn’t grasped the exchange between the two women. The archivist’s rude tone of voice tells him nonetheless that the situation is deteriorating. But he keeps his calm and turns his attention to the other pieces of the puzzle set out in front of him. Apart from the bit of skull, he is able to observe the wooden structures of the sofa, including the head-rests. As well as the photographic report from the time of the counter-inquiry into Hitler’s suicide in April–May 1946. This series of black-and-white photographs that we saw last year shows the site of the suicide, with traces of blood on the sofa and the wall. “We can’t talk about blood traces,” Charlier says prudently. “At this stage we can only talk about traces of blackish drips.” More than half a century has passed, and they still appear on the light-coloured wood, probably pine, of Hitler’s sofa. The passing of time and GARF’s very poor conservation conditions have not erased them. If these are authentic pieces and not a trick perpetrated by the Russian secret services. Anything is possible in this inquiry, including the worst. “I think it would be difficult to make such a forgery,” Philippe Charlier reckons. “All of these traces can also be found identically in the photographs from 1946. It would demonstrate astonishing counterfeiting skill if it was a copy.” Lana tells Charlier: “You can touch them if you like, you can handle them; look here, where there are traces of…” The forensic expert utters a cry as he sees the journalist bringing her hand towards the object. “No! Don’t touch! You’ll contaminate this piece of evidence with your DNA.” Lana apologises with an embarrassed laugh. “That’s exactly what you mustn’t do,” Charlier says apologetically. “And it’s bound to have happened several times. That’s why I’m not expecting much from these bits of sofa. They have been badly preserved in non-sterilised fabric. Plainly this wood has been touched by numerous hands, directly, without protective gloves. And that’s without the spittle that many observers have deposited on them. The only DNA that one would find here will be from a few minutes ago. Hitler’s will have disappeared long ago.” Then, after a moment’s thought, he goes on: “We can hope for nothing from that side. Unless…”

While he leans over them, keeping a respectable distance (without running the risk of adding his own DNA by tiny drops of sweat or saliva) from one of the pieces of sofa, the forensic expert has another idea. He turns his attention towards the photographs from the Soviet inquiry. Then back to the pieces of evidence. That back-and-forth movement speeds up. He picks up one of the chairs around the table and begins a strange demonstration. “This is very interesting. Exciting. Look…” His enthusiasm even communicates itself to the two archivists, who are drawn to him in spite of themselves.

“Let’s imagine that the victim is on this chair. He has just fired a bullet into his skull. His head is on the head rest, the blood flows and bounces off the floor, causing splashes. He talks quickly, waving his hands around. Wounds to the head always bleed abundantly. The blood must have flowed in large quantities, even for only a few minutes, the few minutes between the shot and Bormann and Linge’s arrival in the antechamber. The blood spread across the floor, thick, heavy, dark, whether on the concrete or on a carpet. Carpet or concrete, it doesn’t really matter. There will have been so much blood that a puddle has formed, and the drops that are still falling splash the sofa, but not just anywhere: under the sofa. And here are those splashes!” On one of the pieces of the sofa tiny dark stains mingle with the natural veins of the wood. Sometimes, depending on the lighting, they almost disappear. The scene of the crime, of the suicide to be precise, is coming into focus. Does Charlier’s hypothesis agree with the witness statements? Linge, the valet, and Günsche, the personal aide-de-camp, came into the room. They told the Soviet investigators who had taken them prisoner what they saw.

Interrogation on 26–27 February 1946 of prisoner of war Linge Heinz, former Sturmbannführer SS.

Linge: “There was a lot of blood on the carpet and on the wall near the sofa.”

Interrogation of prisoner of war Sturmbannführer SS and Hitler’s servant, Günsche Otto, 18–19 May 1945.

Question: When did you first enter the room where the suicide occurred and what did you see?

Answer: I entered the room at 16:45. I saw that the carpet on the floor had moved slightly and that there was a bloodstain.

After the liberation of the Soviet camps in 1955, Linge’s interminable interrogation sessions in the Russian prisons would resume: “‘How much blood sprayed on the carpet?’ ‘How far from Hitler’s foot did the pool of blood extend?’ ‘Where was his pistol exactly?’ ‘Which pistol did he use?’ and ‘How and where was he sitting exactly?’ These were some of the stereotyped, endlessly repeated questions I was obliged to answer.”*

Philippe Charlier is able to give those answers. Or at least some of them. He abandons the pieces of wood, which are unusable for DNA tests, and comes back towards the bit of skull. He picks up the box. He plays with the light to get a better look at the dark traces that cover part of it. “As I thought,” he says under his breath, as if talking to himself. “These are not organic remains from an individual. No skin or muscle. It’s all been burned. I clearly see traces of carbonisation. They prove that it has undergone prolonged thermal exposure.” The expert is more interested in other stains. “I think we are looking at traces of soil here. Perhaps even traces of corrosion or rust. Do we know where the skull was discovered?”

Thanks to the files found in the archives, we know quite precisely.

Go seven decades into the past–to 30 May 1946. Thirteen months after Hitler’s suicide, the area around the Chancellery in Berlin was subjected to a new inspection, organised within the top-secret context of the “Myth” file, launched on 12 January 1946 by Beria’s successor in Internal Affairs, Sergei Kruglov. Teams of investigators brought in especially from Moscow got to work in the Führer’s headquarters. They had received very precise orders from their superiors:

Top Secret

“APPROVED”

Vice Minister of Internal Affairs

of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

Colonel General: I. Serov

16 May 1946

Plan of operational investigative activities into the circumstances of Hitler’s disappearance.

In order to clarify the circumstances of Hitler’s disappearance, the following measures must be undertaken:

I

1. Draw a map (to scale) of the location of the new and old Reich Chancelleries as well as Hitler’s shelters (bunkers); photograph the sites.

2. Proceed to the internal inspection of Hitler’s shelters as follows:

a) draw a map of the arrangement of the rooms in the bunker.

b) photograph the rooms occupied by Hitler and Eva Braun.

c) proceed to the inspection of all furniture preserved in these rooms, as well as the walls, floors and ceilings, for a possible detection of any traces that might shed light on the circumstances of Hitler’s disappearance.

d) inquire into the question of the current location of the furniture previously removed from the bunker and examine them.

e) in order to identify the preserved furniture and establish their arrangement in the rooms occupied by Hitler and Eva Braun, Linge, Hitler’s former valet, should be brought to the site after having been previously questioned on the subject.

f) Study the place where the corpses of a man and a woman were found by the exit to the shelters in the garden of the Reich Chancellery for a possible detection of objects that might be of importance to the inquiry.

3. Inquire into the location of the personal objects that previously belonged to Hitler and Eva Braun but which were removed from the bunker. Examine these.

II

4. Perform a new medico-legal autopsy of the bodies of a man and a woman discovered in the garden of the Reich Chancellery during the first days of May 1945 to establish the age of the deceased, the signs and cause of their death.

5. To this end it is necessary to exhume the bodies and transport them to the locations specially equipped for the purpose in the hospital in Buch.

On the basis of the results of the activities listed above and the materials previously collected, investigations will have to be undertaken according to a new plan.

The principal goal of the teams of the Ministry of Internal Affairs was to find the missing part of the body found in May 1945. In their autopsy report dated 8 May 1945, the forensic examiners had recorded the absence of the back left-hand part of the head. Very quickly, in May 1946, two pieces of skull were disinterred in the garden, three metres from the entrance to the Führerbunker. Precisely where the alleged bodies of Hitler and Eva Braun had been found on 4 May 1945. One of the pieces had been pierced by a bullet. Might that fragment of bone not be the missing piece of the puzzle? In that case, the theory of suicide by poison was seriously weakened. What if it was true that Hitler had committed suicide not with cyanide but with a bullet? The discovery of these two bits of skull might put an end to speculations about his death. For that to happen, it was enough to check that the bones belonged to the corpse attributed to Hitler. Nothing could be simpler, since the Ministry of Internal Affairs was fully supportive of the inquiry. Except that the corpse in question was still kept under the jealous surveillance of the Ministry of Defence.

For several months, the head of Soviet counter-espionage, Viktor Abakumov, had enjoyed almost total impunity in the chain of command of the USSR. Stalin had made him his new right-hand man. Abakumov took advantage of the fact to act as he saw fit. So on his own initiative, on 21 February 1946, the SMERSH officers based in Germany moved the corpses not only of Hitler, but also of Eva Braun, of the Goebbels family (parents and children) as well as that of General Krebs. Until now these bodies had been buried in a wood near the little town of Rathenow. No justification was given at the time to the Soviet authorities.

Top Secret

ACT

21 February 1946 3rd Shock Army of the Soviet Occupying Troops in Germany

The Commission [of SMERSH] has drawn up the present act stipulating that on the above date, in accordance with the instructions of the head of the counter-espionage service “SMERSH” of the Group of Soviet Occupying Troops in Germany, Lieutenant General Comrade Zelenin, near the town of Rathenow, we have exhumed a grave of bodies belonging to:

– German Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler.

– His wife Eva Braun.

– The Reich Propaganda Minister, Dr. Josef Goebbels.

– His wife Magda Goebbels and their children–son Helmut and daughters Hildegard, Heidrun, Holdine, Hedwig [only five out of six children are listed; Helga, the eldest daughter, is missing]

– The head of the general staff of the German Army, General Krebs.

All of these bodies, consumed by putrefaction, are in wooden boxes and have been transported in this state to the city of Magdeburg, to the headquarters of the counter-espionage department “SMERSH” where they were reburied. They were buried at a depth of 2 metres in the courtyard of number 36 Westendstrasse, near the stone wall to the south of the courtyard, 25 metres from the garage wall of the house to the east.

The grave has been filled with earth and flattened at ground level, giving the spot the appearance similar to the surrounding landscape.

Why move such important corpses? Abakumov did this to keep control of his “trophy.” The headquarters of SMERSH in Magdeburg, 150 kilometres south-west of Berlin, offered perfect protection against the “snoopers” of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. It was quite natural for the bodies to be moved there. It was most important that they should not be taken to the Berlin hospital in Bunch for a new autopsy.

The Kremlin supported Abakumov, because a few weeks later he was appointed Minister of State Security with the rank of general. Then he was appointed a member of the committee of the Politburo of the Soviet Communist Party, in charge of legal affairs. At the age of only thirty-eight, he was not only untouchable but also terribly dangerous for anyone daring to challenge him. A position that he planned to exploit.

The request by the “Myth” file team to perform a second autopsy on the bodies moved to Magdeburg was rejected out of hand by counter-espionage. But the directives of the Ministry of Internal Affairs did not lack clarity. Lieutenant Colonel Klausen, in charge of the inquiry in Berlin, brought with him a mission order that he thought was sufficient.

Top Secret

To the Deputy Head of the Operational Department of Gupyi, MVD (Ministry of the Interior), USSR, Lieutenant Colonel Klausen.

These orders have priority. You must leave for the city of Berlin under the command of Lieutenant General Serov in order to carry out the special mission of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.

We ask all military organisations of the MVD and the occupying Soviet administration to support Lieutenant Klausen in every possible way from his arrival at his destination until his return to Moscow.

Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs of the Union of SSR

Lieutenant General Chernishov

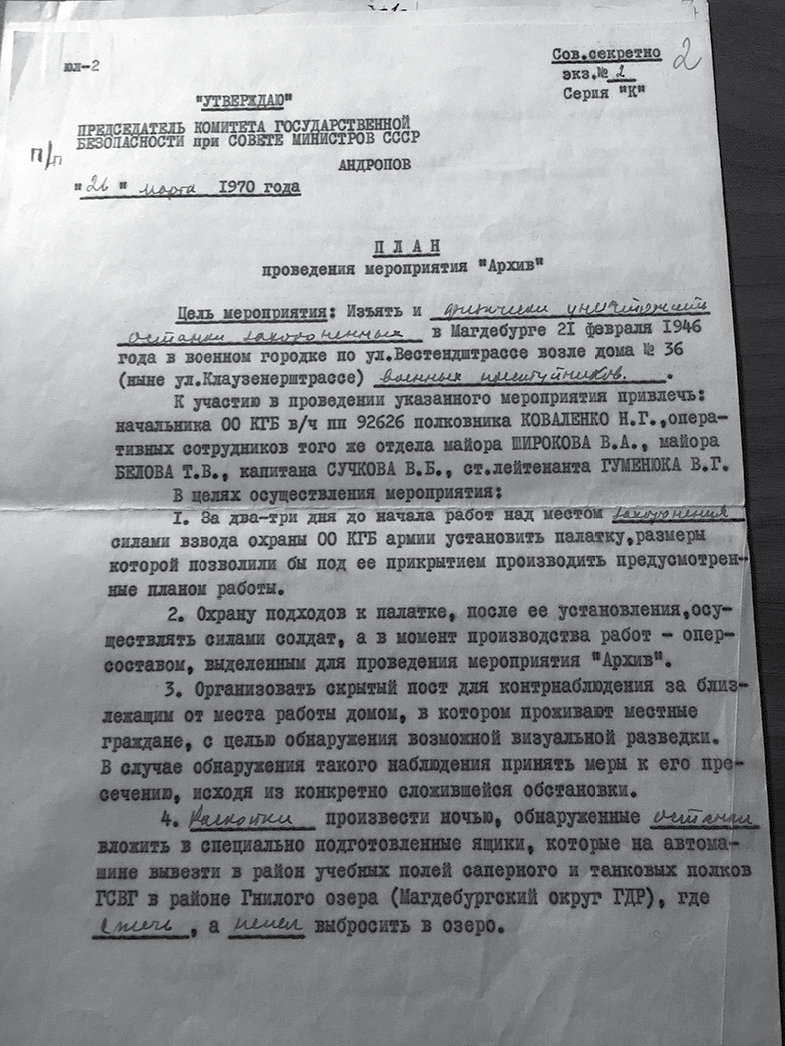

This mission letter did not make enough of an impression on the SMERSH agents. They were answerable to the Ministry of Defence and had nothing to do with the other ministries. Because of their refusal, no one would ever be able to compare the two fragments of skull with the rest of the male corpse, either in 1946 or in any other year. Never. In spring 1970 all the bodies buried in Magdeburg and under the control of counter-espionage were definitively destroyed. This decision was taken at the highest level of the state by one Yuri Andropov, future leader of the Soviet Union (from 1982 until 1984). In 1970, Andropov already occupied a key post in the nexus of the country’s secret services. He was the all-powerful “President of the Committee of State Security in the Council of Ministers of the USSR.” In short, the man was in charge of all the Soviet spies. No “special” operation could be decided without his agreement. Like the one code-named “Archive,” for example.

Purpose of the operation: to exhume and physically destroy the remains buried in Magdeburg on 21 February 1946 in the military town on Westendstrasse near house no. 36 (now Klausenerstrasse), which are those of war criminals.

Why decide twenty-five years after the fall of the Third Reich to destroy these skeletons? Did the Kremlin fear that the state secret might one day be revealed and that Hitler’s body, if it was indeed his, might fall into the hands of the Western Allies? Or, more simply, did the Soviet rulers want to move on from an old story and get rid of defeated enemies once and for all? Moscow would not have to justify its act, because it was secret.

A colonel from the Special Department of the KGB ran this highly sensitive and confidential mission. In the early 1970s, Europe was in a state of major geopolitical tension. The German zone under Soviet administration had declared its independence from the rest of Germany in 1949. It took the name GDR, the German Democratic Republic, and obeyed the orders of Moscow. This was the era of the bipolar world (on one side the capitalist camp dominated by the United States, on the other the Communist camp led by the USSR), and the fear of a Third World War. Officially, Moscow continued to deny that it was in possession of Hitler’s body. Operation “Archive” intervened in this complex geopolitical context. Everything had to be totally secret. As usual, the Kremlin was suspicious of everyone, first of all its own men. Precise instructions had been issued in this spirit.

For the operation to be put into effect, it will be necessary to proceed as follows:

1. Two to three days before the start of works on the burial place, the men of the protection platoon of the SD [Special Department–author’s note] of the KGB have to set up a tent large enough for the activities covered by this plan of action to be carried out beneath it.

2. The protection of the means of access to the tent after its establishment must be carried out by the soldiers and, when the work is being carried out, by the operational personnel specially dedicated to operation “Archive.”

3. Organise a hidden post from which to supervise the house near the site of the operation and inhabited by the local population in order to detect any potential visual observation. In the case of the discovery of any such operation, take measures to counteract it on the basis of the current situation.

4. Perform the excavation at night, place the remains found in specially prepared boxes, evacuate them in the vehicles of the engineering regiments and armoured vehicles of the GSVG [Group of Soviet Forces in Germany] in the region of the “rotten” lake (Fall See) (district of Magdeburg GDR) or incinerate them and throw the ashes into the lake.

5. Document the execution of the activities indicated on the plan by the writing of acts:

a) act of exhumation of the interred remains (in the act indicate the state of the cases and their content, the procedure of placing the latter into prepared boxes);

b) act of incineration of the contents of the interment.

The acts must be signed by all operation agents listed above […].

6. After the removal of the remains, the place where the interment took place must be returned to its original state. The tent must be removed 2–3 days after the major work is complete.

7. The “cover legend” given that the operation is being carried out in a military town where access is forbidden to the local population, the need for an explanation of the causes and nature of the work, may apply only to officers, members of their families and civilian functionaries of the army general staff living in the territory of the town.

The justification of the “legend.” The works (installation of the tent, excavation) are carried out with the intention of verifying the depositions of a criminal held in the USSR, according to which precious archive documents may be found in this location. […]

Mission orders for the KGB secret operation “Archive” concerning the complete destruction of the bodies of Hitler and Eva Braun, 26 March 1970. This document is stored in the archives of the FSB in Moscow.

It is rare to be able to consult such a Soviet secret services document. Even though it is over seventy years old, it remains confidential. It is no coincidence that it is preserved today in the archives of the FSB (ex-KGB). It shows us the internal working of a special operation with the use of “legends,” scenarios intended to offer a credible cover to spies. What is surprising in the present case is that this “legend” was intended to fool soldiers of the USSR.

Operation “Archive” was officially taken to its conclusion. The alleged bodies of Hitler and his inner circle, Eva Braun, the Goebbels family, and General Krebs, have been definitively destroyed. At least that is the version provided by the Soviet secret services and validated even today by the Russian authorities. Here is that report in its entirety:

Top secret

Unique copy

Series “K”

Magdeburg (GDR)

u.m. [military unit] No. 92626

5 April 1970

ACT

(On the physical destruction of the remains of war criminals)

According to the plan of operation “Archive,” the special group consisting of the head of the Special Unit of the KGB in the Council of Ministers of the USSR u.m. No. 92626, Colonel Kovalenko N.G. and military men of the same unit, Commander Chirikov V.L and Senior Lieutenant Gumenuk V.G., on 5 April 1970 has incinerated the remains of war criminals after removing them from their place of burial in the military town at Westendstrasse near house No. 36 (now Klausenstrasse).

The destruction of the remains was effected by means of their combustion on a pyre on waste ground near the town of Schönebeck, eleven kilometres from Magdeburg.

The remains were burnt, crushed to ashes with coal, collected and thrown into the River Biderin, which is confirmed by the present act.

Head of Special KGB Unit u.m. No. 92626

Unique copy of the report on the success of operation “Archive” carried out by the KGB, dated 5 April 1970 and stored in the FSB archives in Moscow.

As in the days of SMERSH and the NKVD, quarrels between different Russian administrations continue even today. The flag has changed, but not the mentalities. As proof of this, will our authorisations to study the skull carry much weight with the two GARF archivists? Philippe Charlier consults the photographs of the Chancellery garden, taken in May 1946 when the fragments of skull were brought to light. A pile of metal debris covers ground violently ripped open by the artillery fire of the battle of Berlin. A small cross drawn in pencil on the photograph indicates the exact place where the two bits of skull were found. Just outside the entrance to the bunker. It was only later that the Russian scientists put the two fragments together to make one. The one archived in the offices of GARF.

“So these bones were buried under rubble in the middle of large numbers of metal objects.… This is important information. Remind me how long this bit of skull has been under the ground?” Each piece of information has its own importance. “Buried for over a year in this ferrous pool? That would be a match. At any rate, the scenario is not out of the question,” Charlier reflects. “In plain terms, the bits of skull that we have in front of us show every sign of having been buried for a long time in corrosive ground.”

Those are the positive points. Now for the negative ones.

“Isn’t handling the skull under your surveillance exactly what we came here to do?” Philippe Charlier tries to persuade the archivists in his turn. Dina is unwilling to yield. She asks Nikolai. He replies by picking up the box holding the piece of skull. “Another time,” he says without looking at us. When? Tomorrow? Soon? It’s Dina’s turn to speak: “We don’t know if we will have time to receive you. You will need a new authorisation.” But we’ve got it! Lana insists. Nikolai has already left with his trolley. He almost flees into the corridor. It is 8:00 in the evening. We have abused their patience quite enough.

* https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZqrrjzfnsVY

* Heinz Linge, With Hitler to the End, op. cit., p. 213.