5

Pillage

We were scared. We thought they had come to take us away. . . . But the Germans just took all the books . . . and left.

—Avraham Negrin, president of the Jewish community of Larissa, Greece, on events of July 1942

Many of the texts that the RSHA and the ERR, Alfred Rosenberg’s task force, looted from Europe had been created in distant lands, in ages long past. The provenances of some involved great tales of adventure and survival even before the books fell into the hands of Nazi henchmen. One manuscript in particular was a medieval Egyptian edition of a text that had first been composed in the second century BCE. The manuscript had spent many centuries in a genizah, a dark, attic-like room in Cairo, heaped together with thousands of other texts and fragmentary documents, before making its way to France and eventually into the ERR piles of plunder. For most of that time scholars knew that the text it contained had once existed, but nobody had seen it for centuries.

What saved the text, and indeed what allowed it to reappear after it had been lost almost one thousand years earlier, was the great value that Judaism sees in the written word. As explained in chapter 1, Jewish law considers written texts so sacred that it forbids the disposal of them, insisting that they be “interred” in a genizah, instead of thrown away.

On May 13, 1896, Rabbi Solomon Schechter, then the only Jewish faculty member at Cambridge University, was running errands in downtown Cambridge when he ran into his good friend Mrs. Agnes Lewis. Mrs. Lewis told him that she and her sister, Mrs. Margaret Dunlop Gibson, had just returned from a trip to the Middle East, where they had purchased some old Jewish manuscripts. Accomplished amateur scholars versed in Hebrew, Arabic, Greek, Syriac, and many other languages, the sisters had been able to identify most, but not all, of the old documents. Would Rabbi Schechter be interested in coming over to help?

Of course he would! Schechter headed straightaway to Castlebrae, the Gibson-Lewis mansion, where he sat with the sisters at their dining room table and began paging through the ragged bundle of papers. Some of the manuscripts represented rare versions of the Jerusalem Talmud and were quite valuable. The collection seemed to have come from Fustat, the oldest neighborhood of Cairo. Schechter had heard rumors of a sizable genizah there; in all likelihood, that was where the sisters’ dealer (or the dealer’s supplier) had gotten the documents. Then Schechter came to another manuscript, and his heart skipped a beat. It was a tattered page with two partly faded columns of Hebrew writing. Schechter suspected—and later confirmed—that the manuscript was a page from the original Hebrew of the book of Ben Sirah, also called Ecclesiasticus.

It was an astounding discovery. Ben Sirah is an ancient book of Wisdom Literature (similar in some ways to the biblical book of Proverbs) that for a variety of reasons hadn’t made the cut into the Hebrew Bible; Protestant Scripture left it out as well. By the early Middle Ages, however, Catholic scholars such as Saint Augustine had identified passages in the work that resonated with Catholic theology and included it in their Bibles. The version they included, however, was based on later Greek translations of the work. The original Hebrew had last been seen by the Babylonian sage Saadia Gaon, whom we met in chapter 1, and Saadia Gaon had died in the year 952. Since then the original Hebrew of Ben Sirah had been lost to history. Or so everyone thought.

After Schechter and the sisters announced their find, librarians around Europe dove into their own piles of old Jewish manuscripts in search of Ben Sirah. Within a few weeks, librarians at Oxford’s Bodleian Library announced that they had identified several additional Ben Sirah manuscript pages, some of which came from the very same copy as the one that Schechter had identified at the home of Mrs. Gibson and Mrs. Lewis.

Schechter traced the manuscript to the genizah at the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo, Egypt. A few collectors and manuscript dealers had already discovered the trove, and a handful of its contents had hit the manuscript market—Schechter himself may have even seen a few of them. For the most part, however, nobody had paid it any attention. Now Schechter paid attention. As soon as he could, Schechter traveled to Cairo and secured permission to enter the genizah. There, to his astonishment, he found a pile of almost three hundred thousand ancient and medieval manuscripts. It was a discovery of literary treasure unparalleled in scope and magnitude before or since.

Schechter packed up almost two hundred thousand of the manuscripts to take back to Cambridge for further study, where he hired a team of scholars and assistants to help him sort through the material. The additional staffing not only allowed more manuscripts to come to light, it also allowed Schechter to search through the crates for manuscripts that were of particular interest to him. In short order, he too found several more pages of Ben Sirah.

Although Schechter had removed a massive amount of material from the genizah, he left behind some one hundred thousand manuscripts that didn’t interest him. Other collectors and dealers descended on the synagogue, hauling off the last of the Cairo Genizah’s contents by 1911. Among the manuscripts that Schechter left behind were still more pages of Ben Sirah in its original Hebrew.1

One of those pages made its way into the hands of Baron Edmond James de Rothschild. Unlike other members of his prominent banking family, Edmond de Rothschild was far more into collecting and philanthropy than he was into business. He was an ardent supporter of Zionism, he had an astounding collection of art, and his library—particularly his collection of Judaica—was second to none. Among its many treasures were fifteen hundred manuscripts from the Cairo Genizah, one of which was our page from Ben Sirah.2 Rothschild donated a significant portion of his Judaic library to the Alliance Israélite Universelle, a Paris-based organization devoted to protecting Jewish communities around the world and to promoting Jewish education. When World War II began, the Alliance’s library consisted of fifty thousand volumes (of which twenty were incunabula) and about eighteen hundred manuscripts, including that trove from the Cairo Genizah.

On August 7, 1940, barely a month after Germany conquered France, agents of the ERR entered the eight-story library of the Alliance Israélite Universelle and got to work packing up its precious collection. They cleared the shelves and placed what they grabbed into fourteen hundred book crates; they found and removed a secret safe containing three hundred manuscripts of different kinds, and they also looted the Cairo Genizah manuscripts.

A new, dark chapter in the epic story of the Ben Sirah manuscript had begun. Inscribed in the Middle East many centuries earlier, in time it became faded and tattered, and eventually it was placed in the Cairo Genizah chamber with thousands of other Jewish documents. There it remained until the late nineteenth century, when a collector or dealer removed it and the manuscript eventually found its way to an ornate Parisian palace belonging to the wealthiest Jewish family in the world. Later it was donated to the library of one of the world’s leading Jewish organizations. And now the Nazis had it.

In the summer of 1940 France opened like a treasure chest before Alfred Rosenberg’s eyes. As we saw earlier, the Nazi campaign against Jewish books had begun even before Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, exploded in a spate of book burnings immediately afterward, and then exploded again as part of the violence of Kristallnacht in November 1938. But in a civilized country like Germany, campaigns of rapacious pillage and genocidal murder must grow slowly. Confiscating a collection here and impounding a library there might have been okay before the war, but now the fate of Europe’s Jewish literary collections would be decided by men like Rosenberg—men whose goal was nothing less than acquiring all of Europe’s Jewish books. How was Rosenberg to get his hands on them? For an answer to that question, he would have to wait.

Alfred Rosenberg’s hands were particularly tied in Germany itself; his authorization to claim Jewish books was limited to the occupied territories, which meant that he couldn’t loot the material within the Reich’s borders. For the time being he’d have to content himself with book-rich France and elsewhere. On May 10, 1940, Germany invaded France, defeating its army by late June. At the time France was home to about 350,000 Jews.3 Now, with Germany in control, its large Jewish communal and organizational libraries were Rosenberg’s for the taking. Furthermore Jews throughout the country were fleeing their homes or going into hiding, and more often than not, they left their books behind. Finders, keepers. And as an added benefit, the Freemasons were also laying low, and Rosenberg was convinced that they and other ostensibly innocent organizations were actually part of the Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy bent on destroying the Aryan race. Rosenberg spent the summer getting his ERR machine up and running. He appointed Baron Kurt von Baer as head of the ERR’s operations in Paris, and soon the ERR established a French national headquarters and four regional offices in the city. With the help of the Gestapo and other police organizations, Rosenberg and his men branched out from there. They spread through the country in search of artwork, books, archives, and other cultural treasures. Using information gleaned from police address lists, storage inventories, and documents of French shipping companies, they searched castles, warehouses, farms, and private homes—anyplace where they might find some of the precious loot they sought.

Despite their totalitarian approach, Nazi civilian and military leaders needed to maintain at least a pretense of legality as they went about their pillaging. Often such legal cover came easily. For example, Nazi policy deemed all “abandoned” property to be the property of the state and thus fair game for Rosenberg and his task force. As a result the chateau of a Jewish resident of Bordeaux who fled to the United States for safety, or the home of a Parisian Jew who had been arrested on his daily errands, or the offices of a small Lyon business whose Jewish owner had gone into hiding were all legally deemed state property, as were the items within these places, giving Rosenberg and other Nazi looters free rein to take what they wanted.

It was a magnificent banquet of riches, and the ERR sidled up to the table and heaped its plate high. Along with 50,000 volumes from the Alliance Israélite Universelle, they plundered 10,000 from the city’s prominent rabbinic seminary, L’Ecole Rabbinique. The ERR took 4,000 volumes from an umbrella group, the Fédération des Sociétés Juives de France (Federation of Jewish Societies of France), 20,000 from the Lipschuetz Bookstore, and another 28,000 from the private collection of the Rothschild family. Later sweeps of the city’s private homes in the city yielded thousands more books, enough to fill 482 crates.4

The ERR pillagers also helped themselves to a priceless haul at the Chateau de Beaumesnil, in Normandy. The seventeenth-century baroque edifice, surrounded by well-groomed walkways, manicured gardens, and a moat, was home to Hans Furstenberg, a wealthy Jewish banker and bibliophile. Not only did the palace house Furstenberg’s 16,000-volume library of priceless first editions, incunabula, and fine bindings, but by the time of the invasion it also held material from the Bibliothèque Nationale and the Archives de France as well. The curators of those collections had asked Furstenberg to hold parts of their collections; keeping the material out of Paris, they hoped, might keep it out of Nazi hands.

It didn’t work. In the fall of 1940 a crew of ERR officials drove past the Beaumesnil gardens, traversed the moat, and entered the palace. They packed up its libraries and shipped the books to a central storage facility. Some of the material was never recovered.5

15. Books discovered concealed in an Amsterdam synagogue. Courtesy Yad Vashem Photo Archives.

As Nazi forces swarmed through France in the spring and summer of 1940, so too did they march into the Netherlands. Germany conquered Holland’s grand cities and its windmill-powered farms, and here too the ERR swept down on the country’s Jewish books. They took millions of them. In Amsterdam alone the haul included 25,000 volumes from the Bibliotheek van het Portugeesch Israelietisch Seminarium, 4,000 from the Ashkenazic Beth ha-Midrasch Ets Haim, an unknown number of antiquarian treasures from the private collections of Sigmund Seeligmann, and fully 100,000 from the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana.6

Some of the ERR’s greatest hauls were valuable not because of their quantity, but because of the matchless nature of the collections they took. For example, in the fall of 1940 the head of Rosenberg’s operations in the Netherlands, Oberbereichsleiter Schimmer, brought a group of ERR soldiers to the Spinoza Society in The Hague and the Spinoza House in Rijnsburg, and they packed the “Spinoza Library” into eighteen shipping crates. Baruch Spinoza (1632–77), widely considered to have been the father of modern Jewish thought, owned a handsome collection of 159 volumes: Aristotle, Machiavelli, Rabbinic literature, and more. When he died, a notary catalogued the 159 volumes in his library, and the collection was promptly sold at auction. Later, in 1900, a Dutch philanthropist used the old inventory to re-create the collection; he purchased identical printings of the books that appeared on the list, thus amassing a facsimile of the Spinoza collection. Schimmer somehow missed the “facsimile” detail and seems to have thought that the books he and his soldiers removed were the very same ones that had once belonged to the philosopher. “Not without reason,” he reported, “did the director of the Societas Spinozana try, under false pretenses which we uncovered, to withhold the library from us.”7

The books weren’t Spinoza’s, but they were old, and they were valuable. And now they joined millions of others in the growing pile of Nazi loot.

As the ERR machine roared up to full speed, the RSHA accelerated too. While the ERR was confined to conducting its operations outside the Reich and in the occupied territories, the RSHA was under no such limitation. As a result the RSHA—particularly Dr. Six and his Department VII—implemented an extensive book-looting campaign within German borders and beyond. More than one hundred sizable collections fell prey to the RSHA book behemoth, and probably many other smaller ones as well. They took more than two hundred thousand volumes from twenty-six different collections in Berlin, tens of thousands more from nine collections in Breslau, and thousands more from eleven libraries in Frankfurt. There were also collections from smaller communities, such as Ulm, Glogau, and Trier. In short, the RSHA’s sweep through Germany denuded the nation of its Jewish books, leaving behind only a skeleton of empty bookshelves as testimony to the great literary collections that once enlivened its many Jewish communities.8

Many entries in the catalogues of looted work assembled after the war are both tantalizing and tragic in their vagueness. For example, one entry describes a looted collection from Mayence that contained memorial books and other precious material dating back to the late thirteenth century:

Bibliothek der Israelitischen Religionsgemeinschaft, owned by the Jewish Community.

Valuable library with rare documents and some mss.

Outstanding is the Nuernberger Memorbuch [Neurenberg Memorial book]; first entry: 1296.

Included collection of Rabbi Dr. M. Lehmann.

Sources: Menorah (Vienna), 1927.

Siegmund Salfeld, “Das Martyrologium des Nuernberger Memorbuchs,” in Quellen zur Geschichte der Juden in Deutschland (Berlin 1898), vol. 3.9

Some of the material that the ERR, RSHA, and other Nazi organizations looted during the war was later recovered; much of it was not. If their goal was to preserve Jewish cultural treasures, they failed, for much of what they collected was subsequently lost. If their goal was to destroy Jewish culture, they failed at that task too. Most of the works they sought to possess for themselves now survive in the hands of others.

For Our Youth

For most German Jews, books were the least of their worries. Living under the specter of arrest, deportation, and death, they were usually worried far more about their basic survival than the fate of their libraries. On their way to the train stations, they often locked their front doors, leaving behind most or all of their worldly possessions—their furniture, clothing, kitchen utensils, rugs, linens, financial records, lamps, family photos, knickknacks . . . and the contents of the bookshelves lining their walls.

Wolfgang Lachmann was one of those whose books were left behind, but he hardly remembers them. He was born in Berlin in 1928 and was only five years old when the Nazis came to power. His parents, like many German Jews, were avid readers, and over the years the Lachmann family accumulated a nice collection of several hundred books. At first Wolfgang had a pretty normal middle-class German childhood—school, a dog, a bike, and summer vacations with his family. His maternal grandfather had fought for Germany during the First World War at Verdun. Lachmann’s father joined the army himself just before the war ended, and after his military service concluded, he became a businessman and remained a proud and patriotic German until the day he died.

Things began to change for Wolfgang and his family in the mid-1930s. Like the other Jewish kids, when the Nazis came to power he had to drop out of his neighborhood public school and attend a school for Jewish children on the other side of town. After Kristallnacht, November 1938, things became especially difficult. “My father’s business was all smeared up on the outside with ‘Jewish Store’ kind of a thing,” he told an interviewer for the U.S. Holocaust Museum in 1992. “It was painted with big letters and people were standing outside and discouraging customers from going in.”10

The following summer Wolfgang’s mother fell ill with what turned out to be leukemia, and she died a few months later. He and his father moved to his maternal grandmother’s home, whereupon his father contracted tuberculosis and died in 1941. The following January, Wolfgang’s grandmother received a letter ordering her and the other residents of her home—that is, Wolfgang—to report to a local synagogue about ten days later. Each member of her family would be allowed to bring one suitcase weighing no more than thirty kilograms, about sixty-six pounds. As they prepared to leave, Wolfgang’s grandmother filled out a form listing everything in the home—two armchairs, seven pillows, twelve glasses, balcony furniture, a stamp collection, and 350 books. With the exception of a French dictionary, the eight-page document did not list any details about the individual volumes in the Lachmanns’ home library.11 Later, as he and about one thousand other deportees left the synagogue to board the trucks waiting outside, the principal of Wolfgang’s elementary school stood at the door handing out hard candy to everyone who passed by. To Wolfgang’s surprise, the principal remembered him.

The chronology of Wolfgang’s life for the next several years is one that is both tragic and sadly typical to students of the Holocaust: the Riga Ghetto, a few small concentration camps, Bergen-Belsen; starvation, loss, and despair; liberation in April 1945. Eventually he moved to the United States, changed his first name to Walter and dropped an n off of his last name, got married, had a family, and started a business.

In 2008 an article appeared in the German magazine Der Spiegel announcing that a team of librarians in Berlin had discovered that, scattered in their collections, were thousands of books that had once belonged to Jewish families who had left Berlin during the war. According to library records, Berlin’s Jews had “gifted” them to the state on their departure from the city. Reading the article in Orange County, California, Rabbi Lawrence Seideman came across a detail that quickened his pulse. Immediately he picked up the phone and called a friend of his. “Walter,” he asked, “who is Wolfgang Lachmann?”

“Why, that’s me,” said the voice on the other end of the line. “It was my name before I came here from Germany.”

The detail that caught Seideman’s eye was an account from Detlef Bockenkamm, a curator at Berlin’s Central and Regional Library, describing his discovery of a Jewish children’s book: “One was titled For Our Youth: A Book of Entertainment for Israelite Boys and Girls. The book contained the handwritten dedication: ‘For my dear Wolfgang Lachmann, in friendship, Chanuka 5698, December 1937.’ Bockenkamm has been unable to find out what happened to the boy.”12 Seideman shared the article’s description of the children’s book with his friend Walter . . . Wolfgang, who immediately cried out, “That’s my book.”

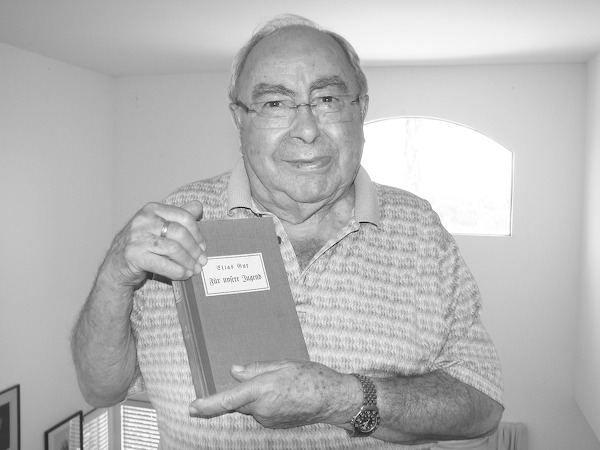

16. Walter Lachman, reunited with a book that was looted from his home when he was a child. Courtesy Walter Lachman.

Walter Lachman had no specific recollections of that particular volume—he had received it from a teacher when he was nine years old and, in all likelihood, had placed it unused on the shelf and never gave it a second thought. In 2009 he was scheduled to travel to Berlin to be reunited with his childhood book. However, the previous week his wife had fallen and injured herself, so Lachman sent his daughter to receive the copy of For Our Youth on his behalf. Aside from the standard-issue cap he had kept with him from his days in Bergen-Belsen, the book his daughter handed to him upon her return represented his only physical connection with his life in Germany.13

The Mini Italian Bible

The Jewish community of Rome, Italy, is the oldest in Europe; Jews have lived in the city ever since the second century BCE. For most of that time they lived in the shadow of the Vatican and consequently encountered oppression of all kinds: poll taxes, humiliating dress codes, expulsions, torture, forced conversions, and murder. This oppression would reach its zenith, of course, during the years of World War II.

The history of Roman Jewry, however, was not simply a two-thousand year crescendo of oppression—far from it. There were many good times too. Though a large number of Jews arrived as slaves during the second century CE, many early popes tolerated and even provided active support to Rome’s Jews. In the Middle Ages the city was home to prominent Jewish sages, poets, and philosophers. As we have seen, Rome was also an important center of Jewish printing and publishing for centuries. The city was home to Jewish print shops as early as 1469, and many of those early books still exist today. In 1492 thousands of Jewish refugees from Spain found safe haven there. Around them were magnificent Christian domes, pillared palaces few Jews would enter, and ruins of a civilization once bent on destroying their own. And yet, even as they faced persecution, these Jewish refugees made the city their home and often thrived. By the late 1930s the city was home to twelve thousand Jews.14

During the war the two significant Jewish libraries in Rome were both housed in the same building—the Central Synagogue. On the third floor was the library belonging to the Italian Rabbinical College. Most of the stacks were open to the students, who used the volumes regularly, and a Jewish librarian who visited Rome at that time doubted that its books were of much monetary value.15 The books in that seminary library were, however, the primary tools of instruction for the country’s Jewish religious leaders, and they were thus of great value indeed.16 On the second floor of the synagogue building was the Jewish Community Library. Unlike that of the seminary, this library’s collection was not open to the public. In 1893 one of Rome’s historic synagogues had burnt down, and the destruction of its priceless antiquities became a tragic reminder of the literary treasures that Rome’s Jewish community needed to preserve. Immediately they gathered the books from five local schools into the library that now sat above the synagogue.17

In 1934 a scholar named Isaia Sonne catalogued part of the collection, and the list he assembled illustrates how truly priceless it was. The library held incunabula, early publications of the famous Sonsino Press, antiquarian books from other Italian cities such as Venice and Livorno, not to mention books from beyond Italy’s boarders—from Constantinople, Salonika, and elsewhere. It held priceless manuscripts, palimpsests, archival material, and much more. Sonne’s catalogue was seventy pages long,18 but it included only part of the collection—there were about seven thousand books in all.19

At least one book in the seminary’s library was of historic and monetary value. It was a small Bible, pocket-sized really, about four by seven inches. The book was published in Amsterdam in 1680, and the ivory-colored leather in which it was bound had scalloped over the years, giving it a wizened, wrinkled appearance. On the spine was a sticker—clearly printed long after the book itself—with the words “Biblioteca di Collegio Rabbinico Italiano” and handwritten shelf markings inside an ornately designed box around the edges. Inside the right cover was a bookplate bearing a similar design.

Although Italy had long been rife with antisemitism, the deportations and mass murder of the Holocaust came late to the country. In the early years of the war Italy strove to maintain its independence from Germany, and as a result Mussolini and other Italian leaders refused to allow the country’s Jews to be deported to Nazi death camps. But the summer and fall of 1943 were a time of chaos in Italy: Mussolini was overthrown and arrested; Italy’s new government signed an armistice with the Allies; Germany rescued Mussolini from prison and reinstated him to power. Mussolini, resolved to show his allegiance to his Nazi patrons, decided to give the Reich full access to its Jews.

17. A seventeenth-century Bible returned to the Jewish community of Italy. Courtesy Unione delle Comunità Ebraiche Italiane (Union of Italian Jewish communities).

In late September Herbert Kappler, head of the Gestapo’s unit in Rome, called in the leaders of the local Jewish community and informed them that he could guarantee the safety of Rome’s twelve thousand Jews for the reasonable fee of fifty kilos of gold—the equivalent of about $56,000, or about $4.50 per person. Not realizing that their deportation orders had already been signed, and not seeing that they had any other choice, the Jews of Rome quickly gathered the money and made the payment on September 28. They breathed a sigh of relief. Rosh Hashanah was to begin the following night, and having paid their ransom, they might be able to celebrate the new year in peace.

On the day of September 29 the synagogue staff arrived at work and thankfully began what they thought was to be a normal day in the office. Soon, however, a military convoy consisting of several trucks and two tanks rumbled up to the building. Forty soldiers climbed out of the trucks; officers, translators, and machine-gun-wielding guards stationed themselves around the building.20 The officers knocked on the door of Ugo Foà, president of the Jewish Community of Rome. There were rumors, they told him, that Roman Jews were collaborating with the enemy and hiding anti-fascists in the synagogue. They had orders to conduct a search immediately.

Without delay, the officers entered the synagogue and conducted their “search”—quite a thorough one in fact. They broke into the synagogue’s charity boxes, destroyed one of its arks, and threw two Torah scrolls to the ground. Adding to the desecration, the soldiers also carried away several boxes of archival material, which, among its historical records, held the contact information for almost every Jew in Rome.21

The Gestapo soldiers and officers who entered the synagogue that afternoon were bent on little more than destruction, intimidation, and the gathering of names of Rome’s Jews for future deportations. On the following day, however—the first day of Rosh Hashanah—two ERR officers showed up to inspect the second and third floors of the building, particularly the libraries. They returned the next day for a closer look and informed Foà that he was to provide them with the catalogues of the books in the two libraries—the ERR needed the information for their “studies.” On October 11 the ERR officers returned yet again, this time with a man the local Jews understood to be a German scholar with expertise in book publishing. Giacomo Debenedetti, a witness of these events who survived the war, later provided a vivid description of him:

Like the others, from head to toe he is all uniform—that close-fitting fastidiously elegant abstract, and implacable uniform, which, tight as a zipper, lock in the wearer’s body and, above all, his mind. It is the word verboten translated into uniform; access forbidden to the man and to the personal experiences he has lived through, to his past, and truest uniqueness as a human being on this earth; access forbidden to the sight of anything but his present, stern, programmed, unyielding.22

After yet another inspection of the library, this tightly uniformed officer and his colleagues informed Foà that he and his fellow Jews were to consider the contents of both libraries as officially impounded. No books or archival material could be removed, and anyone caught violating the order would be subject to severe corporal punishment. From the synagogue they called a shipping company to make arrangements for the material to be removed.

Ugo Foà and the Dante Almansi, president of the Union of Jewish Communities, wrote a letter to local fascist authorities appealing for intervention. Their efforts, unfortunately, were of no avail. Two days later a man from the shipping company arrived at the synagogue to begin arranging for the shipment of the books. By October 14 all of the material from the Jewish Community Library and some of the material from the Rabbinical College was packed and loaded into three train cars for shipment.

One of the boxes in that shipment most likely contained the small Dutch Bible printed in 1680; perhaps it was crammed into a crate with other, less valuable volumes, perhaps the soldiers could see its value and gave it a box of its own. Regardless, it, along with thousands of other books from the Roman Jewish libraries, was now in the hands not of Jews devoted to studying them, but of Nazis—Nazis who claimed to be devoted to studying them as well.

Two days later, beginning at 5:30 a.m., Nazi soldiers rampaged through Rome, gathered all the Jews they could find, and sent them to Auschwitz. Many Jews escaped, but more than a thousand did not, and they were murdered soon after they arrived at the camp.23

Late that December, Nazi officials went through the abandoned Rabbinical College to pack and ship the remaining books. Nobody is certain what happened to the books of the Roman Jewish libraries. The most widely accepted theory is that most of them fell into Soviet hands after the war and promptly melted away into the holdings of state-owned libraries throughout the Soviet Union.24

That’s why it was such a surprise when, on May 10, 2005, at a symposium in Hannover, Germany, about the looted libraries from World War II, Frederik J. Hoogewoud, a librarian from the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana in Amsterdam, called forward Dario Tedeschi, an attorney who was there representing the Jewish community of Italy. They were in a conference room at the Wilhelm Leibniz Library, brightly illumined by sunlight streaming through its large plate-glass windows. Hoogewoud had just given a talk about the fate of some of the looted material when he called Tedeschi forward and presented him with one small volume, ivory-colored, with a scalloped cover. It had been printed 325 years earlier, coincidentally in Amsterdam, where it had landed after the war. Nobody knew exactly how it had gotten there, but now it was time for the book to travel from Amsterdam to Rome once again. It was time for the book to go home.

Books from the Jerusalem of the Balkans

From the City of Seven Hills our attention turns to the east—across the boot of Italy, across the Adriatic Sea, and across the Aegean Peninsula. Soon we find ourselves in a bustling portside city, the medieval ramparts of its old fortifications now surrounded by red-tile rooftops, domed church steeples, and the chockablock apartment buildings of a modern Greek metropolis. We have arrived in Salonika, a city whose thriving, centuries-old Jewish community has earned it the all but official appellation of “the Jerusalem of the Balkans.”

By the time of the war, Salonika had long been one of the largest and most highly cultured Jewish communities in the world—home to accomplished Jewish merchants, high-ranking Jewish officials in the secular government, and many renowned rabbis and other Jewish intellectuals. Its Jewish cemetery was the largest in the world, and on the eve of World War II the community consisted of about fifty-five thousand Jews. Jews composed such a large percentage of the city’s total population that stores in the city closed on Saturdays rather than Sundays.

In 1917 a massive fire swept through the city, destroying many of its neighborhoods and synagogues, and devouring countless irreplaceable books and manuscripts in the process. As a result, Salonikan Jewry cherished its written words even more dearly in the decades to come. With such a rich literary life, it should be no surprise that Salonika was also home to a lot of Jewish books. And as a place with so many Jewish books, it should be no surprise that it was a prime target for the ERR and other Nazi book-looting organizations. As early as May 1941 Rosenberg had ordered teams of ERR officials to sweep through Greece and collect its literary treasures. It was here that Johannes Pohl got his start in the field of Jewish book looting. By November a unit of more than thirty ERR officers, with the full support of the SS, had taken rare books, manuscripts, and other cultural treasures from forty-nine synagogues, bookshops, organizations, and more than sixty private homes.25

The extent of the pillage is perhaps best described by Rabbi Isaac Emmanuel in a memoir he wrote about his experiences after the war:

Some time after the invasion, there arrived in the city a delegation from the “Rosenberg Unit,” one of whose members was Dr. Pohl, director of the Hebrew Faculty at the University of Frankfurt. He went through libraries and private homes and looted many priceless books (he was knowledgeable, for example, about books on Judaism and the history of Salonikan Jewry. He came to the home of my father, the wise and righteous Samuel [may God avenge his blood], to see his library and he took whatever he saw fit). After him came another researcher, Hans Heinrich, and the two of them emptied Salonika of all of the valuable books belonging to dozens of scholars and wealthy individuals, an ancestral legacy. Among the noteworthy books that disappeared on this occasion from the Jews of Salonika were about ten thousand volumes of rabbinic responsa, Jewish legal literature, the significant library of the revered Rabbi Chaim Chabib, which included several handwritten manuscripts belonging to him, and the rabbinic library belonging to the descendants of Rabbi Nahmias, several priceless books in Ladino that remained in Jewish homes that were in middle-class neighborhoods in Kalamaria and in [the] Baron Hirsch [neighborhood], neighborhoods that were not burnt down in the year 5677 (1917), and the library that was renovated by Rabbi Nehama. Even if we take into account only the various manuscripts and the Ladino literature that they looted or completely destroyed, this is an enormous loss, whose value is impossible to calculate (all of this spiritual treasure was destroyed along with its owners). . . .

The community was forced to pay the living expenses of the members of the Gestapo, the Rosenberg Unit, and forty Jewish collaborators who were brought from Germany in order to assist in the pursuit and oppression of the city’s Jews.26

In other places, the looting was befuddling as well as frightening. For example, Avraham Negrin, president of the Jewish community of Larissa, Greece, tells what happened to the Jewish books in that community:

“On a Shabbat morning in July 1942, while we were praying in the Kehal, the Germans came in and took away our books. Our Chacham Yitschak Cassuto cried out, quoting the Psalms [94:1]: ‘O Lord God to whom vengeance belongs; O God to whom vengeance belongs, shine forth.’

“We were scared. We thought they had come to take us away, just as they had rounded up Salonika’s Jews in 1942. But the Germans just took all the books from the Talmud Torah and left.”27

And so it went. In town after town, city after city, country after country, Nazi conquests led to the opening of invaluable cultural treasures to Nazi thieves bearing in their uniforms and official-looking paperwork the imprimatur of one of the twentieth century’s mightiest nations. Teams of looters would go into newly conquered towns to collect all of the Jewish books they could find. Often with the help of Jewish conscripts, they would sort through the material to select what was most valuable and destroy the rest.

It had taken centuries for the Jews of Europe to fill their bookshelves. It was taking far less time for the Nazis to empty them.

Overall, the rules of Nazi looting were markedly different in eastern Europe than they had been in the west. In France, Holland, and other western lands, the ERR obtained lists of deported and otherwise departed Jews from local authorities, entered their homes, inventoried the goods, and made off with their haul. Comparatively speaking, this was polite looting. Civilized. In western Europe the Nazis conducted their looting efficiently. They stole Jews’ books with the sophistication of a modern megastore accounting department, though of course with the scruples of a looting Mongol horde.

In eastern Europe the situation was different. For one thing, most organizations in these lands were run by the state; there were far fewer private schools and libraries. In fact all Soviet libraries had been nationalized during the 1920s and 1930s, when the Soviet government had taken the material and sold off the most valuable books to collectors and dealers in the west.28 Looting in the Soviet Union, therefore, was a government-to-government affair, uncomplicated by screaming children, teary-eyed parents, and all the other unpleasantries involved in stealing from private citizens. There were some confiscations from individual communities in the Baltic states, such as Latvia and Lithuania, but on the whole the ERR confiscations in the east were from large libraries that had belonged to national governments for many years.

But not always . . .

Solly and Cooky’s Math Book

Books open the world to us. Each page can describe times and places and realities utterly unknown to readers beforehand—the whir of electrons around a nucleus, the strategic movements of Napoleon’s troops, a phantasmagorical tale of knights and dragons and wizards. Books, we readers know, can be marvelous at describing not only the here and now, but also the there and then. They can bring us more fully into the world and also help bring us to worlds both real and imagined that are very different from our own. And it is this very ability—the ability that books have to pull us away from the local and out of the present—that made them so popular during the Holocaust. Books could be an escape, and as a result, during World War II Jews reached for their books with ravenous hunger.

In the early 1940s a young Lithuanian Jew named Solly Ganor saw his mother display just such a hunger. Ganor had been born in the town of Heydekrug near the German border in 1928, and his family had moved to the larger city of Kovno when Hitler came to power in 1933. In 1941, as part of the Nazi effort to render the Jews of eastern Europe more easily accessible and easily murderable, the Jewish section of Kovno was established as a ghetto, eventually becoming a temporary home to tens of thousands.

Like countless others, the Ganor family lost its home and had to move into the overcrowded ghetto. And like so many others, they left behind extended family, friends, career, and community in the widespread upheaval of war and murder so rampant in Lithuania beginning with the Nazi invasion of 1939. Several relatives were deported and never heard from again. Friends died of starvation and disease. Solly’s brother Herman was killed in a provisional concentration camp not far from Kovno.

Solly Ganor’s mother, however, had one means of escape from the growing darkness—books. Specifically, she turned to a ten-volume anthology featuring the works of Tolstoy, Pushkin, Dostoevsky, and other Russian literary greats. The books, bound in red leather with gold-embossed lettering, were among her most cherished treasures. “Like me,” Ganor later recalled, “she escaped from her grief by reading. She would sit almost motionless for hours, only moving two fingers to flip the pages.”29

Not surprisingly, the Nazis would not allow her to have the books for long. On February 27, 1942, the ERR executed a “Book Action” in the Kovno Ghetto. An order went out demanding that all books be brought to a two-story house serving as an assembly point, where Jewish conscripts who knew Hebrew had been put to work sorting through the material to identify the books valuable enough to save.30

Tearfully Solly’s mother helped him load her ten volumes into a makeshift sled so that he could take them to the appointed spot. Fourteen-year-old Solly, however, wasn’t as ready to cooperate. He and his friend Cooky found an abandoned house at the outskirts of the ghetto and hid the books there instead. Some of Solly’s neighbors were eager to get rid of their books too, and soon the boys had gathered several hundred volumes—books in Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian, and other languages. When Solly tapped into a contact he had at the German collecting point, he was able get his hands on still more books, and the size of their library grew to about one thousand volumes. It represented the Babel of eastern European Jewry, gathered together as contraband on several carefully hidden shelves in Kovno.

Originally the boys collected books for their own use—he and Cooky, he recalls, each read about a book each day. In short order, however, word of the boys’ collection spread, and other kids approached them with books of their own to trade. Evidently Solly and Cooky weren’t the only budding clandestine librarians in the ghetto.

At school, Solly and Cooky studied carpentry under their favorite teacher, Mr. Edelstein. A shy and kind man, Mr. Edlelstein had somehow managed to maintain a positive outlook on life despite the fact that in the shtetl where he grew up, the Nazis had recently locked up all the Jews in the local synagogue and burned them alive. None of Edelstein’s relatives had survived.

Although he was hired to teach carpentry, Edelstein also taught his students mathematics and other forbidden topics, sometimes throwing in a Zionist lesson as well. One day Edelstein approached Solly with a request. He had heard that his young student had access to books. Might Solly be able to get his hands on some mathematics textbooks? If he could procure some, Edelstein told Solly, he would be very grateful. Solly got right on it, and the next day he handed a forbidden math book to his teacher. Edelstein’s face lit up. “Do you know what a treasure this is? Look! It is in Hebrew and was printed in Tel Aviv. Where on earth did you get it?”

The ensuing events unfolded with sickening predictability. When Solly left school that afternoon, he saw Edelstein bargaining for food with a Nazi guard. The guard spotted the book and drunkenly yelled at Edelstein. An SS officer pulled up, examined the book, and demanded to know where Edelstein had gotten it. The beating began. Solly, standing just ten yards away, made momentary eye contact with Edelstein; imperceptibly Edelstein gestured to Solly that he should leave. Solly ran, turned a corner, and heard a gunshot. Looking back, he saw Edelstein fall to his knees. The SS man aimed the gun and fired again. Edelstein fell to the ground and lay still.

“Me and my stupid books!” Solly lamented in a memoir he wrote four decades later. “For the first time, I realized the danger I exposed everyone to with my foolishness. I wouldn’t listen and now my teacher was dead. To this day, I remember his feeble gesture waving me away from there. All he had to do is point in my direction to save himself, but he wouldn’t do it.”31 Edelstein was buried in an unmarked grave. When the weather warmed, Solly planted some peas at the site. “To my surprise,” he recalled, “they grew into bushes and eventually bore fruit, which Cooky and I shared. I knew that Mr. Edelstein wouldn’t mind.”32

At the ERR and RSHA collecting points across Europe, the books rolled in. They came by the box at first, but soon the boxes gathered in precarious heaps and were moved from place to place on pallets, and eventually the pallets outran their usefulness. When the books were coming in at a more measured pace in Germany, France, and Holland, the Nazi book-gathering agencies tried to catalogue them. But as the eastern European collection program grew, the books burst out of their shelves and overflowed in a deluge across warehouse floors. Cataloguing such a fast-growing collection would have been impossible, and storing them neatly on bookshelves would have been akin to gathering the floodwaters of a hurricane in drinking glasses. Even trying to do so would have been pointless and downright foolish.

What were they to do with this massive and rapidly growing mountain of literary material? Where were they to put it? For Rosenberg, of course, the original idea was to gather the books and archives as materials for the Institute for Research into the Jewish Question that the führer had authorized him to open in Frankfurt. But the institute existed only on paper. It didn’t yet have anything even remotely resembling a functioning facility where it could store its library and archival material. In fact during World War II, Frankfurt was hardly the kind of place that anyone with half a brain—perhaps an apt description for Rosenberg and his associates—would want to build anything. And the same was true for most cities in Germany. Rosenberg’s counterparts at the RSHA and other Nazi looting organizations faced the same challenges. The great academic institutions of their dreams didn’t exist yet, but the libraries of those nonexistent institutes had millions of books. Clearly Rosenberg and the others would need to figure out how to store the books until after the war.

Since Rosenberg’s first major acquisitions came from the Rothschild Library in Frankfurt, and since the plan was for the research institute to be headquartered in that city after the war, Rosenberg’s staff sent most of the Jewish books to Frankfurt. At first. But then, in 1943, Allied forces bombed the city, and it no longer was a safe storage site for the Nazis’ growing pile of literary loot.

They looked to Hungen, a small city about thirty miles to the northeast of Frankfurt. Hungen’s fourteenth-century castle, renovated during the 1870s, was well situated for the task at hand. It was close enough to Frankfurt to be convenient, yet far enough away to escape the bombs and other depredations of war that might imperil the collections. The half-timbered, Bavarian-style castle was vacant, and it was right near the rail line running through town. It was perfect.

So, beginning in 1943, the ERR shipped the bulk of its Jewish books to Hungen. By the end of the war the ERR had shipped a few million volumes there.33 Its Masonic material, on the other hand, went to a nearby hunting lodge in Hirzenhain or directly to the RSHA for them to dispose of as they wished. Not only had Frankfurt suffered from the ravages of Allied bombing, but so too had the ERR headquarters in Berlin. When its leaders realized that Berlin wasn’t a safe place to store books either, they turned eastward again, more specifically to the southeast. The Silesian city of Ratibor, now called Racibórz, was also a convenient site for their storage needs. Not only was it closer to the eastern looting sites, but like Hungen, it too was situated with easy access to rail lines. And of course, since it was in the east, Rosenberg and his ERR officials had free rein when it came to choosing buildings for their facilities.

18. Schloss Hungen. Courtesy Freundeskreis Schloss Hungen.

As in many of its activities, the ERR moved into Ratibor with gusto. In May 1943 it set up an office in a building that had once been a bank. In mid-August, an advance team of four officers arrived in the town and arranged housing for twenty people. Furniture arrived—looted furniture, of course—and in short order barges carrying six thousand crates of books and other confiscated material arrived at a nearby river port. It took seventy freight cars to carry the shipment from the docks to the Ratibor storage facilities.

The ERR set up its headquarters in the local Franciscan monastery and then took over some nearby barracks for office space and additional storage. Still more storage was designated at a former bathhouse that had also been a Jewish center. More offices went into the library, and the ERR turned a warehouse into a movie theater. The local synagogue had been badly damaged in a 1938 fire, but the ERR renovated it to house a large portion of its library holdings, particularly those from the Soviet Union. Additional material went into a large building on the main market square that had once been a Jewish-owned department store.

Evidently Ratibor itself wasn’t big enough for what the ERR needed, so it took over facilities in other parts of the region. They stored the deluge of books in a cigar factory in nearby Paulsgrund, a cigarette factory in Kranstdädt, and castles in or near the towns of Tworków, Gratenfeld, Schillersdorf, and Oberlangendorf. One of their most important sites was the castle of the Princes Von Pless, in the city now known in Polish as Pszczyna, which became an ERR branch office and collecting point. Some members of the family that owned the castle were invited to continue living there as cover; evidently they were never told the true nature of what was going on in their home.34

Once the ERR set up shop in Ratibor, the city become the central sorting point for all of its steadily growing collections headed to the Hohe Schule: 61 cases of priceless works from the library of Baron de Rothschild, looted in early September 1943; 1,940 from the opulent Château de Ferrières, in Ferrières-en-Brie, France; another 22 cases from Elene Droin-Rothschild; 16 from an attorney named Albert Wahl; and the list goes on.

The former synagogue served as the repository for most of the books from the east, but other buildings took the piles of archival material: 394 crates from Mogilev, 17 wagonloads from the Lenin Library in Minsk, scholarly material from Smolensk, and other collections from Kiev, Riga, and Kharkiv. We tend to think of depositories of this type of material as single buildings, hidden warehouses. With regard to Ratibor, however, such an image would be on far too small a scale. From 1943 until the end of the war, Ratibor was, in many ways, a hidden city of archival and bibliographic loot. Books there filled castles, warehouses, former religious and cultural centers, and other buildings too numerous to list. Additional buildings provided lodging for the staff, recreational facilities, and other infrastructure necessities. It was a city of literary jewels, and its rulers were Alfred Rosenberg and a team of Nazi soldiers.

If that weren’t enough, the ERR also took over the monastery in the Austrian town of Tanzenberg. There, by the end of the war, it had assembled six hundred thousand of its finest books—volumes that it had set aside for the Hohe Schule library—rare volumes from various Rothschild libraries, incunabula from other German and French collections, priceless material from Soviet collections. Unlike Ratibor, the Tanzenberg material had generally been vetted and was stored there by virtue of its high value and desirability.

Like the ERR, the RSHA had its own set of castles and other repositories where it sent its own books. It left about half the collection in Berlin, where much of the material was destroyed by Allied bombs before the end of the war. Of the Jewish library material that the RSHA removed, a large portion of it was allotted to four castles in the Sudetenland (more or less the modern-day Czech Republic): Niemes, Böhmish-Leipa, Neu-Pürstein, and Neufalkenberg.35

The RSHA had one additional repository on its list of major Jewish book destinations, only this one wasn’t a magnificent palace or mountaintop monastery; it was an overcrowded, walled-off slum where 140,000 Jews lived, most of whom died before the end of the war.36 The Nazis first formulated their plans for the Theresienstadt Ghetto in October 1941, and by the following May the operation was up and running. The idea was for the small garrison town first built in the eighteenth century to serve as a collecting point for Czechoslovakian Jews. There they could be housed, given a few morsels of food, and later sent to the extermination camps to be murdered. Additionally Theresienstadt could provide cover for the Nazi extermination of Jews; it could be a “model Jewish settlement” and thus preserve the Reich’s image in the court of world opinion.

In building this “model community,” the Nazis had a lot to work with. Among the Czechoslovakian Jews sent to live in Theresienstadt were a good number of artists, writers, and scholars. As a result, a rich cultural life arose in the ghetto despite the miserable conditions in which its residents lived. There were several orchestras, an opera, and different types of theaters. There were clandestine religious activities. Each week there were dozens of performances and lectures for the high-minded and low-browed alike.

And there was also a library. It started small—six staff members and one room with stacks holding about four thousand books. Most of the books were RSHA loot: Judaica and Hebraica sent to Theresienstadt after it was no longer safe in Berlin. Many of the other books came from the ghetto inmates themselves. The Nazis searched prisoners on all of Theresienstadt’s incoming and outgoing transports—those coming in with new prisoners, and those leaving with downtrodden others bound for the death camps. Invariably, most new prisoners brought one or more of their favorite books with them, hoping in vain to be able to read the books while living in the ghetto. These volumes too ended up in the library.

The Jews of Theresienstadt devoured the books. Czechoslovakian Jewry was, as a whole, a modernized and highly assimilated community when the war began. Many of its members had never studied anything about Judaism before, let alone learned the Hebrew of its ancient texts. The Holocaust, however, shook everything up. Ghettoization had turned the world of these acculturated and assimilated Jews upside down. In Prague or Bratislava, a Jew could easily hide his or her ethnic and religious background. Here in the ghetto, however, one’s Jewishness was not only public knowledge, it was also the defining factor in one’s life . . . and perhaps in one’s death. Rather than reject it, Jews by the thousands turned to their Judaism with eager passion and read everything they could on Jewish subjects.

Soon the library outgrew its one-room facility, and in June 1943 a reading room opened. Books by the thousands rolled in. People flocked to the library. Their reading appetites were voracious. There was a banquet of literary riches available to them, and they couldn’t get enough. Soon, a checkout system was put into place. To get a library card, a patron had to pay fifty ghetto Kronen (the money was worthless anyway) and prove to the librarians that they had received a higher education (most had). Since it was hard for some ghetto residents to get to the library facility, a bookmobile system was created, which brought boxes of thirty books to various parts of the ghetto. There were book groups, small libraries set up in group homes around the ghetto, technical and professional libraries, and a well-utilized children’s library of thirty-five thousand volumes. It took fifteen librarians and dozens of support staff to oversee the collection.

Inevitably some books disappeared. Paper was a precious commodity in the ghetto, and desperate prisoners often repurposed the pages of library holdings into the fuel and toilet paper they so urgently needed for their very survival. Still, the Jews of Theresienstadt yearned to read. And with such an intense demand for literature, not to mention a growing population, it soon became hard for readers to get hold of the books they wanted. One inmate named Rudolph Geissmar gave voice to this frustration in part of a poem he wrote in the camp titled “Dedicated to the library”:

I am lying abed and would like to read something

And have already submitted several requests

And each time you were accommodating.

But what I got I had already studied before.

Be once more nice and send me something

Because here a body has time. . . .

But please no thin and lightweight books.

No, rather something to chew on, heavy and hard.

. . . at least something serious and good.

I place my wish confidently in your hands.

And obediently and in good mood look forward

To a well-meaning gift.

Theresienstadt was a show camp—gussied up for visiting foreign dignitaries and inspectors not only with a beautiful library, but also with orchestras, nice schools, and spacious barracks. But during the final months of the war, after the inspectors had left, transports left the camp carrying most of Theresienstadt’s inmates to their deaths at Auschwitz and other death camps. By the end of the war, there were one hundred thousand books in the Theresienstadt library, and the collection was overseen by a single librarian, Emil Utitz, and his assistant, Käthe Starke.37

By then, of course, there were no readers.

How many books, all told, did the Nazis loot? The number is astoundingly difficult to calculate. In Poland the Nazis pillaged more than 100 libraries, stealing more than a million books in all, 600,000 from Lodz alone. They took 700,000–800,000 in Belgium and the contents of more than 200 libraries in Belarus. It’s easy to get lost in the numbers. The first postwar catalogue of all the looted books came out in 1946. It listed 704 separate collections, including the number of volumes thought to be in many of them, but the numbers for many others were unknown. At the end of the war, there were 10–12 million volumes in the Soviet Union and anywhere from a few hundred thousand to a few million at each of several different collecting points in western Europe. In the end we’ll never know exactly how many books the Nazis stole—“tens of millions” is about as accurate as we can get.38

By means of comparison, the Library of Congress in Washington DC currently holds about 35 million books in its collections. It is entirely possible that the number of books that the Nazis stole from the Jews of Europe was larger than that. In fact it could have been far larger.