The “Character of Members”—Clubs as Interfaces

My strategy here is to tell two tales in tandem—one from the eighteenth century and one from the twentieth—in the hope that doing so will trigger the effect that William Warner and I call “digital retroaction”—a feedback loop between past and present that transforms our experience of both. On the one hand, the current shift into computation provides new concepts, tools, and evidence to bring to bear on the past, altering what we find and how we engage it. On the other hand, our altered histories speak back to the present, inflecting our sense of the futures that might emerge from it. This is, then, an encapsulated version of one of the strategies shaping this entire book.

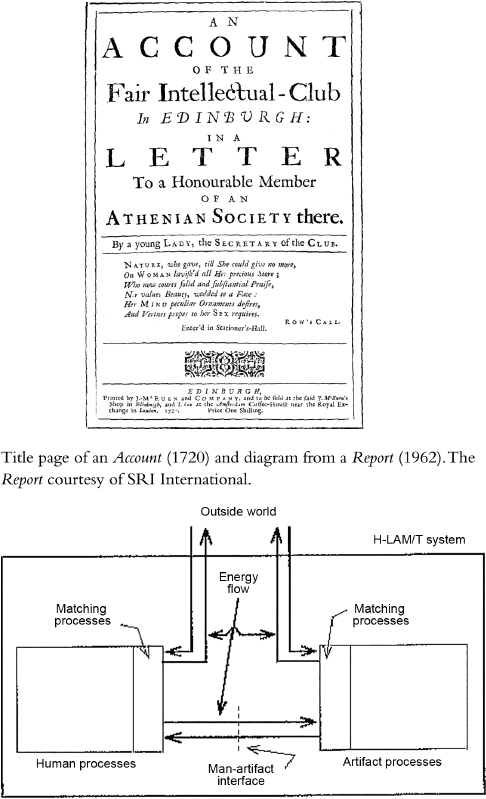

Here are the protagonists of the two tales: a report on Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework by a systems engineer named Douglas Engelbart, from 1962, and An Account of the Fair Intellectual-Club of Edinburgh, 1720. Some readers may recognize Engelbart’s name and realize the importance of the report to our desktops, but for now, let us focus only on the representations on the page in figure 7.1 and then tell the tales. Neither of these representations looks very human—no conventional faces here—but that is because both are meant to enact the volatility of the category: the place where forms of technology and human processes meet to transform each other into something other.

Both the diagram and the title page are mixed forms that communicate through design—shapes and lines and fonts—and through words, words that invoke a further multiplicity of forms: Engelbart’s hybrid form H-LAM/T (Human using Language, Artifacts, Methodology, in which he is Trained) and the eighteenth-century text’s combination of genres—account, letter, poetry—a combination that, as we shall see, serves not just to describe but to constitute the Fair Intellectuals. On the one hand, the title page of the Account can be seen as a diagram, its lines illustrating the flow between the outside world (the “Athenian Society”) and the human (“a young Lady”) inside the club. On the other, Engelbart’s diagram can be read as an account of social interaction between what’s outside (the “world”) and what’s inside the box (the “human” clubbing with the “artifact”). Engelbart, as noted on the diagram, insists that his protagonist is a “system,” and, I will now argue, that is precisely what the club aspired to be.

To understand what these women were aspiring to, we need some sense of where they came from. On the climb up the Royal Mile to its haunting Castle, veer to the left as you cross the wide esplanade leading to the entrance and look over the stone wall. Down below you will see a magnificent turreted building—often mistaken for Hogwarts—whose foundation stone was laid in 1628. Heriot’s Hospital is a hospital in the old sense of the word—a charitable institution often devoted to education. It remains a school today—a school of choice for the children of Edinburgh professionals. Next to the building, you will see some lovely gardens. That is where the account begins a few years before Adam Smith was born.

The account was actually a confession; it revealed a secret—one that was briefly exposed back then but then was reconcealed in the archives. I found it bound deeply into the oblivion of a miscellany in the Special Collections of the University of Glasgow Library. The title page alone tells a strange tale. In 1720 in a print shop in Edinburgh and a coffeehouse in London, an unusual document was put up for sale. “An Account of the Fair Intellectual-Club, &c.,”5 signed “M. C.” and dated July 28, 1719, purports to be the first admission in print of the existence of a small secret society of women formed in 1717 in Edinburgh. Betrayed by one of their own to a gentleman friend, the group felt compelled to protect itself against untoward speculations by clarifying its history and purpose.

The emphasis is on the social; these women came together to work jointly toward a specific goal. The word they used was the same one that Engelbart uses again and again to explain his project: improvement. These women, however, gathered not just for individual improvement; rather, they convened for the “Improvement of one another”—a concept repeated throughout their text. This mutual improvement was necessary, they argued, because of the “Disadvantages that our Sex in General … labour under, for want of an established Order and Method in our Conversation” (6). Entrance requirements were strikingly practical: “at her first Admission,” the new member must deliver ten shillings for the poor and “entertain the Club with a written Harangue” (8). Reading and writing as the bases for inducing proper conversation were their core activities. With a membership limited to nine, like the muses, they took particular interest in the sister arts of poetry, music, and painting.

In addition to the history of the formation of the group, the text includes a description of the “Rules and Constitutions” and transcriptions of talks given by two different members. One of the most striking moments comes in rule XV, which defines the conditions for terminating membership. The two that are specifically named make for a particularly telling pair: you left the club through either “Death” or “Marriage” (9). These are young women—the age of admission was between fifteen and twenty, with only a brief window for intellectual activity before their “mutual Love and Friendship” for each other gave way to men or to some other deadening “occurrence” in the “Course of Providence.” Not only is this—to my knowledge—one of the first, if not the first, club of this type on record at that time in Britain; the use of the term intellectual to describe the club’s purpose was one of the earliest uses of that word in its particularly modern sense: a word designating a very specific set of personal and social behaviors—behaviors to which these individuals aspired.

Their aspiration was transformation, and the technology they deployed was writing—by which I mean again, following Raymond Williams, the interrelated practices of writing, silent reading, and—inevitably, as they discovered when their secret leaked—print. The club’s explicit purpose was to rewrite its members—its secretary, author of this account, emphasizes that the three founders all insisted on a “written scheme” (5). What they in fact wrote down was the imperative to write everything down: “All the Speeches, Poems, Pictures, &c. done by any Member … are carefully kept” (25). Even the oral dimensions of club behavior were grounded in writing: the “harangues” I noted earlier had to be “written” (8).

But why? Why did these young women want to spend their brief moment of freedom between childhood and men immersed in writing? To what end did they write? What did they want out of writing? What did they think writing could do? This is, of course, a strange set of questions for an academic to ask. On the other hand, is there an academic who hasn’t posed similar ones to herself? Perhaps as a thought experiment, then, we might for the moment remove all human selves from the formulation and opt for a Richard Dawkins–like reversal. In his infamous “selfish gene” conceit, human beings are the environment that genes render in order to survive; we are the means to their end.6 In Dawkins’s scenario, they, not us, are the main players in the Darwinian drama of survival of the fittest.

With Engelbart in mind, computer science can also help us think through these issues of causation. A “Theory of Conversation” has become a centerpiece of that discipline’s efforts at interface design. To make software work, computer scientists found they had to ask not only “How does the user tell the software what to do?” but also, in a Dawkins-like reversal, “How does the software tell the user what it can do?”

So here is the reformulation for the Account: why did writing gather humans into groups? One answer, preposterous as it may first seem, was to propagate itself: this was writing’s way to ensure its own ongoing proliferation. Why groups? Because writing had to solve the same kind of reproductive problem faced by the most virulent of the rogue genes we call viruses: what to do when the host population becomes so bedridden that the virus has no means or place to go—when success, that is, threatens the organism with extinction. I am thinking here of Ebola, the terrible disease that consumes its victims from the internal membranes out. We have no cure, but, in many outbreaks in less populated and isolated areas the disease has helped to contain itself by killing its hosts so quickly and efficiently that they cannot spread it very far.7

Think of a human infected by the writing bug; she spends, as we all know, more and more time alone in chairs (if not in bed), all forms of contact disrupted by the isolating experiences of immersion in a book or dissertation or fixation on a blank sheet of paper. For writing to spread—to circulate extensively and efficiently through entire populations—that tendency must be counteracted by new forms of sociability and publicity. In eighteenth-century Britain, the most obvious example was pornography; as the newly public form of private desire, it helped to incite that century’s rise of writing—a role that it appears to be reprising for the new technologies of the Web.

A less obvious but more pervasive behavior was what David Kaufer and Kathleen Carley call “reverse vicariousness.” They use the term to describe how infectious contact with writing was initially and then repeatedly secured—even over the spatial, temporal, and social distances that writing itself opened up (Kaufer and Carley 1993, 12–13). Knowledge of the text need not, they point out, come through the text itself; it can cross the gap

through reviews, and through word of mouth. … Even nonreaders can positively register at social gatherings that they “know of” the book without actually having seen or read it first hand. We might call this phenomenon reverse vicariousness, because we normally think of immediate viewing or reading as vicarious experiences for [the] face-to-face interaction [the text describes]. But, in this case, a viewer or reader uses face-to-face interaction [with others] to experience the viewer or reader role vicariously. (66)

Writing, if you’ll indulge the “selfish gene” conceit a bit longer, puts us into new forms of face-to-face interaction in order to maximize its own circulation. The very technology that threatens to isolate us preserves itself by reinvoking the social through the workings of reverse vicariousness. Thus, the more saturated we are by writing, reading, and print, the higher the premium we put on an expanding repertoire of face-to-face encounters, from improvement clubs to tutorials to cocktail parties.

To see those forms as the invention of writing may sound strange, but doing so allows us to demystify them, particularly the assumption that face-to-face interaction is “real life.” For the Fair Intellectuals, meeting in person meant meeting in writing. Really meeting meant meeting in this mediated way. This is where two of the histories I have been deploying intersect. The history of mediation points to writing as a primary form of mediation at the time these women met. And the history of the real tells us that the large-scale effect of that form of mediation was to alter the experience of the real.8 Starting in the eighteenth century, writing, through reverse vicariousness, made the face-to-face “real”—a connection it made so effectively that in the early twenty-first century, it is still common to be suspicious of anything else, including today’s new technologies of distance communication (e.g., social media, the Web, videoconferencing, virtual reality): we assume them to be less real and thus in some way dangerous (Siskin 2001a).9

Scholarship on eighteenth-century clubs—and on the public sphere in general—has certainly shared this predilection for the face-to-face and the civility we associate with it.10 As we shall see, what the members of the Fair Intellectual-Club saw when they were face-to-face was not each other’s faces, and their behavior was far from civil. Their practice highlights the shortcuts taken by so many efforts at historical inquiry into clubs. In the TLS review of Peter Clark’s important book, British Clubs and Societies (2000), for example, the reviewer simply dispenses with Clark’s arguments to assert that clubbing must be “innate in the British character.” He then posits a cause-and-effect sequence that is not in the book: “English clubs were founded by individuals for no other reason than the wish to be in each other’s company” and “inevitably, bureaucracy soon followed” (Mitchell 2000, 10).

Both Clark and An Account of the Fair Intellectual-Club tell a different story, one in which, I will show, what we think of as bureaucratic systematizing is anything but an afterthought. By focusing on why Britain’s associational world stood out from the rest of Europe, Clark sets the stage for the more specific concerns raised by Edinburgh’s Fair Intellectuals of 1717: Why Scotland? Why so early? Why women?

I have already pulled two key terms from the account of the Club: Improvement and writing. As Davis McElroy has shown, an explicit “impulse toward improvement” in Scotland can be dated well back into the seventeenth century when the Scots Parliament passed legislation “Encouraging Trade and Manufactures” (McElroy 1969, 1). The economic interest was always paired with a moral one, for the Kirk (the Church of Scotland) understood its mission to be ongoing reformation. Fueled by the parallel economic divides between Highlands and Lowlands, and between Scotland and England, as well as the fervor of the church, twin efforts to improve manufactures and morals proliferated.

Those efforts assumed the social form of clubs and societies as the issue of the Union came to a head at the turn of the century. It did so in writing and through a variety of genres, from the reports of church commissions to the record books of the Reformation societies to the new periodicals such as Defoe’s Review. As the colonial fiasco in Darien—Scotland’s failed attempt to establish a trading outpost in the New World—further debilitated the Scottish economy, the debate over the Union became, explicitly, a debate over improvement. With help from “English Farmers, English Graziers, and English Husbandmen,” Defoe wrote, Scottish agriculture would flourish (see McElroy 1969, 6).

When the Act of Union passed in 1707 and Scotland lost its own official state apparatus, the work of improvement fell more fully on church-sponsored and voluntary groupings. Clubbing became a cultural phenomenon in the modern sense of the term, for the act differentiated the political and economic, now linked to England, from what remained under Scottish control: the legal, religious, and educational—those areas, that is, having to do with the passing down, regulation, and valorization of distinctive traits, customs, knowledge, and beliefs. In other words, Scotland was left with the parts that were then totalized into what we would now call culture.11

The technology that built that particular infrastructure was writing, and writing could be said to require, as I have just suggested, groups of humans in order to work. Thus, to find them gathering together in 1717 for the purpose of improvement is not surprising, especially after the failure of the first Jacobite rebellion two years earlier confirmed the new configuration of the Union. What is startling is to find so early in the century young women doing it on their own and in secret—startling, that is, until we put the Fair Intellectual-Club and its members’ predilection for writing into the history of mediation.

Sadie Plant’s (1997) daring and still largely isolated effort to zoom out to a Raymond Williams–like “long revolution” of the relationship of women to technology can help us to put that predilection into perspective. Texts, as Plant notes, are abbreviated textiles in the etymological sense and in the material sense of the woven strands on which we write (69). Her primary argument in Zeros and Ones is that women have been at the secret center of technological change for a long time. Women “gathered at one another’s houses,” she points out, “to spin, sew, weave, and have fellowship. Spinning yarns, fabricating fictions, fashioning fashions …: the textures of woven cloth functioned as means of communication and information storage long before anything was written down” (65, emphasis mine).

The same picture emerges, argues Plant, as we move toward the present—to the start of the electronic era of alternatives to needing to write things down. Once again we find women forming into groups at sites of technological change. In the switching rooms of the first telephone systems, the women operators summoned into groups by the new electronic technology to spin its wires formed informal networks within the formal ones they were paid to maintain. “In several [telephone] exchanges,” notes Plant, “reading clubs were formed, in others flower and vegetable gardens, and a women’s athletic club in another” (123).

To encounter the Fair Intellectual-Club as an episode in this historical sequence is to gain a new and powerful sense of women’s relationship to writing. The turn to that technology—its centrality and its function—ceases to be so mysterious. As with threads into cloth and wires into networks, writing took lines and lives and made them into something different. It offered, in words repeated throughout the Account, “Order and Method” (6). These women didn’t want to feel better; they wanted to be better.

Pleasure, aesthetic and otherwise, was a secondary issue—an effect of the methodizing power of writing. Thus the object that elicits the greatest pleasure in the Account is neither a text nor a painting nor a song but the rewritten bodies of the Club members themselves:

You cannot imagine, Sir, the Joy we had when we found our selves conveened in the Character of Members of THE FAIR INTELLECTUAL-CLUB. For my part I thought my soul should have leapt out of my mouth, when I saw nine Ladies, like the nine Muses, so advantagiously posed. If ever I had a sensible Taste and Relish of true Pleasure in my Life, it was then. (11)

This is improvement: improvement through interfacing with a technology.

In Douglas Engelbart’s terms, this was “augmentation”—improvement generated by what he calls the “matching processes” that allow the human and the technology to alter each other. But what is the basis of this particular matchup? These women clearly understood writing to be the tool that transformed them—that gave to them what they really wanted—“the Character of Members.” But for us to understand how writing accomplished this feat, we need to be more specific, for writing can take other guises and do other kinds of work. What kind of writing are we talking about here? What genre informs and contains all of the other genres of this written account and of the activities it describes, from letter to verse to scheme to constitution to harangue?

The formal feature that gives away the genre of the Fair Intellectual-Club is the one I have already cited: the insistence, in the very first sentence of its Rules and Constitutions, on “Order and Method.” These are keywords of system in the eighteenth century—not system as an idea but as a genre, as in Johnson’s definition of “system” as the “reduc[tion]” of “many things” into a “regular” and “uni[ted]” “combination” and “order.”

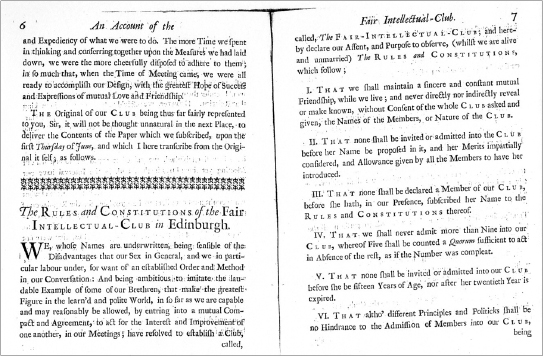

The method and order characteristic of the genre of system not only describe but configure all of the desirable behaviors articulated by the club. The Account itself is structured by them. The sketch of the club’s history is a preface to the list of constitutional rules and thus follows the standard form of written system noted earlier in regard to Godwin’s Political Justice: an enumeration of “principles” embedded in expository prose (see figure 7.2). Those rules in turn clarify the need for and nature of the transcribed harangues that make up the rest of the Account: the inaugural speech by the first speaker of the club and an admissions address given by a new member. The former, in its own words, is about the need for “Order and Regularity” (13); the latter is framed by the secretary as an example of “Method” (25).

Figure 7.2 The rules and constitution of the Fair Intellectual-Club.

If we read them ahistorically—that is, without these generic features in mind—neither the speeches nor their frames seem particularly conducive to intellectual or sisterly harmony. In fact, they come close to confounding them. Far from encouraging reading and writing about the sister arts, “Mrs. Speaker,”12 as she’s called in the Account, spends most of her time warning against the dangers and hazards of such activity—the threat of disorder that they pose. The secretary’s written response after the transcription is, to say the least, surprisingly tart: “I leave you to judge, whether or not the Author of it deserv’d the Chair.” She then reassures the reader that “we have been to this Day as careful to maintain good Order in our Meetings, as she has appeared zealous in recommending it” (24–25, emphasis mine).

The new member’s harangue is presented in a much more positive light, but it too has a surprising twist. Asking from the start why she has been chosen, the initiate dismisses any explanation that has to do with content—her particular virtues or their opinions of them—and focuses instead on the formal structure of the “Occasion”: “Your Goodness and Charity have put you on a Method to try my Respect and Gratitude” (emphasis mine). In other words, now she owes them: “with the Aspect of receiving a Favour you have oblig’d me to be for ever grateful and obedient” (28).

When I found An Account of the Fair Intellectual-Club, I expected a tale of aesthetic pleasures, intellectual freedom, sisterly goodwill, and, quite frankly, a good time, but what I found was order and method—an insistence on “Regulation” (5) that curbs immediate and easy pleasures, demarcates proper subjects, and invites criticism. These could be attributed to individual psychology—perhaps an “innate character”—or, zooming out, to the disciplinary nature of Western institutions, but both of those explanations would miss a crucial historical point. New technologies transform social relations; how they do so depends on the forms the technology assumes. In the eighteenth century in Britain, writing, as I have been insisting, was the new technology and system was one of its hierarchically dominant forms. Eighteenth-century clubs, I am arguing, were the social incarnations of the genre of system, sharing with that genre the informing features of method and order.

The strangeness of that pairing evaporates when we remember Kevin Kelly’s description of system as “anything that talks to itself,” for that is precisely what a club does; you join it because you want to be part of something that talks to itself. Just as the self-regulating power of a thermostat systematically maintains the physical environment, so systematic interfacing in clubs maintains the social; temperature is stabilized in the former, while conversation is sustained in the latter. Clubs proliferate in the eighteenth century because writing brings, in the words of the Account, “Order and Method” into “Conversation.” Written rules and constitutions, for example, allow clubs to be self-regulating in matters ranging from behavior to size, as in keeping the membership at nine.

The Account, then, provides all of the components necessary for Engelbart’s “augmentation.” As the women conformed themselves into the systematic behavior of a club, writing assumed the form of system that Newton’s choice had helped to proliferate. Just a few decades after the Principia, the human and the technology meet (they match up) in system. From that matchup emerges what Engelbart calls the “energy flow” into the “outside world.” That flow took these women from their secret interfacing into the “outside” in terms of both being ready for marriage and of being exposed in the public. At first that exposure entailed the publication of their writing in the form of the Account and then in the form of their poetry—and, as we shall see in the next section, into a different kind of club. But, per Engelbart’s notion of continuous improvement, the “energy” they generated did not exhaust itself back then. After running underground during much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the flow has now reemerged, and not only in this book. In 2014, the Account took the stage in the new form of a play presented at the Edinburgh Festival.13