New Year’s Day dawned cold and raw. The sun remained hidden behind gloomy gray clouds the entire day, and the persistent early morning flurries changed to a chilling rain as the temperature slipped above the 32-degree mark. It was a good day to stay inside, and that’s exactly what most members of the Ewald clan did. Many of them slept late in the morning, particularly the late-night revelers who had attended New Year’s Eve celebrations in the local pubs and didn’t arrive home until the sun was coming up. By noontime, however, everyone was up and around and moving freely. One by one they fixed their own breakfast and gravitated toward the library where the television was documenting the day’s events. Cus and Camille were already engrossed in the spectacular Parade of the Roses from Pasadena, California, that glittery Hollywood extravaganza that precedes the prestigious Rose Bowl football game. New Year’s Day was, after all, a day of parades and football games. From the first note struck by the first marching band in the first parade of the day to the final whistle blown by the referee to end the Orange Bowl in Miami late in the evening, the television set would blare its collegiate message for 14 straight hours. Strangely enough, many people across the country would sit hypnotized in front of their TV set the entire day.

Cus and Camille were joined in the library by Tom Patti, Frankie Minicelli, and Mike Tyson. The boys maneuvered for position in front of the small screen, trying to find the best vantage point without obstructing the view of the elders. Many of the boys settled in for a long day of football, but Tyson was preoccupied with other things. He seemed agitated and was unable to get interested in the festive celebrations on TV. He spent most of the afternoon wandering aimlessly from one room to another. After viewing a few minutes of the Rose Bowl parade, he ambled upstairs to his bedroom and shot pool for 15 or 20 minutes, trying to get his thoughts off his problems. He was particularly worried about his injured left hand. He detested the inactivity brought on by his injury and longed for the action of the boxing ring once again, not the monotonous non-contact sessions against smaller, faster boxers, but full-scale, no-holds-barred brawls against fighters of his own caliber. His hand felt good, and it held up well when he worked the heavy bag, but he hadn’t yet put it to the ultimate test. He hadn’t used his left hand in actual combat in almost six weeks, and he was apprehensive about its condition.

Cus tried to relax his wounded warrior by getting him involved in the exciting Cotton Bowl game from Dallas, Texas. Mike eased down on the floor next to his mentor as the Boston College Eagles and their miniature quarterback, Doug Flutie, took the field to face the Houston Cougars before a chilled crowd of 56,522 screaming fans. The game could not hold Mike’s attention, however, and soon the youngster got up and quietly exited the room. He wandered out into the front yard, preferring to be alone with his thoughts for awhile. As he strolled the river bank in somber meditation, a familiar honking sound caught his attention. Looking up, he was fascinated by a gaggle of Canadian geese soaring high above the house in a typical V-shaped flying formation. They were obvious latecomers to the southward migration, and were heading for their winter quarters in the deep south. The sight of these innocent creatures made the sensitive Tyson yearn for his pigeons. Mike had wanted to build a pigeon coop in the front yard several years ago, but Cus nixed the idea, fearing it would distract his protégé from his primary task. Now, seeing the geese overhead, Mike was once again reminded of his “street rats” from the old tenement days. He decided to ask Cus if he could build the coop now that he was turning pro. Spring would be soon enough to broach the subject.

When he returned to the library, the Rose Bowl was just under way in Pasadena. Mike learned that Boston College had routed Houston 45–28 in the Cotton Bowl, in spite of the fact that Flutie had an off day. Now he joined the rest of the family as they watched USC battle Ohio State, but his mind was a million light years away. Dinner was catch-as-catch-can as the boys of Ewald House, still hungering for more football, protected their positions in front of the TV set to watch the third-ranked Washington Huskies edge the second-ranked Oklahoma Sooners by a 28–17 score in the Orange Bowl.

On January 3, Cus D’Amato and Mike Tyson journeyed to New York City to have Mike’s huge left hand examined by several orthopedic surgeons. To everyone’s relief, Mike passed the tests with flying colors. He received a clean bill of health and was given permission to resume a full training regimen. Needless to say, Mike was overjoyed at the news, as were his two trainers, and the three of them were anxious to return to Catskill to put Mike’s career back on track. While they were in New York City, Cus arranged to visit his good friend, Dr. John Halpin, whose office was nearby at West 72nd Street, across from Central Park. Dr. Halpin and Cus put Mike through one of their hypnosis sessions to get him in the right mental frame of mind for his pro debut. The procedure was pretty much the same each time they sat down together. Dr. Halpin would hypnotize Mike and then Cus would take over, quickly pointing out Mike’s weaknesses, and explaining to the boy how he could turn those weaknesses into strengths. Hypnosis, when used properly, can be an effective tool in helping a person overcome weaknesses and bad habits. In order for the procedure to work, however, the subject must be willing and receptive. In Mike Tyson, the doctor had an ideal subject. Mike wanted to win the heavyweight championship of the world so badly he was willing to try almost anything, even hypnosis, in order to achieve his objective.1

The next day at the Catskill Boxing Club, Mike Tyson was turned loose on the boxing world once again, causing the Tyson triumvirate of D’Amato, Jacobs, and Cayton to convene an emergency meeting of the management committee in New York. It was time to review the final strategy in Mike’s development program, the steps that would be necessary to propel him to the world championship in the shortest possible time. The first step was to remove Mike from Catskill High School and hand him over to a personal tutor. This allowed him to schedule his training program more efficiently and conveniently. It turned out to be an easy decision. Mike had never been able to adjust completely to the small-town school environment, nor was he able to overcome his feeling of inadequacy when it came to his reading and writing skills. He was still taunted by the school bullies who took advantage of the fact that Mike was a boxer and, as such, would not fight back, even though he was twice their size.

The decision to withdraw him from school was a timely one since Mike had just been involved in another classroom disturbance. Some of the tough guys in Mike’s class, the five percenters as Mr. Stickles called them, took pleasure in provoking Mike with a variety of insults, and on this day they followed him up and down the corridors verbally comparing him to “Mighty Joe Young.” When Mike had taken as much abuse as he could stand, he went on the offensive, chasing one troublemaker right through the main office and into the office of the assistant principal, John Turek. Mike might have lost control of himself completely if Mr. Turek had not jumped in between the boys. As it was, Mike tripped and fell as Turek grabbed him, giving the assistant principal the distinction of being the only person in Catskill who ever knocked Tyson down. As Mike became famous, Mr. Turek not only admitted having committed the act, but also embellished the story to his own advantage. During a closed door meeting between D’Amato, Rooney, school principal Dick Stickles, and Turek, it was the unanimous opinion that Mike Tyson’s interests could best be served by allowing him to leave school to pursue his pugilistic endeavors. The parting of the ways was entirely friendly, however, as Mike Tyson had a good rapport with both of the top administrators. In fact, as Mike’s professional career blossomed, he returned to school regularly to visit with the teachers and to talk to the students.2

Mike’s training was in high gear by mid-month, and Cus had his scouts beating the bushes for a new batch of sparring partners. As soon as likely candidates were found, they were herded back to Catskill en masse at a cost of $60 a day. Cus found it necessary to recruit opponents in bunches, because they seldom lasted more than two weeks with the hard-hitting Tyson. His thundering body shots quickly took their toll on his less talented opponents. January turned into February and the Tyson express moved inexorably ahead. Tyson, an intense student of the fight game, trained with complete dedication, often jogging the three miles from his home near Athens to Redman’s Hall prior to his daily two-hour workout. Sparring partners came and went like a 50-cent lunch. Some of them hardly stayed long enough to earn travel money home, and none of them were able to stand up to Tyson’s sledgehammer blows for long. Their names appeared like blurs in the gymnasium register—Nate Robinson, Kenny Davis, Ernie Barr, and Jimmy Young. Some of these men were very capable fighters. They were just overmatched when they stepped into the ring with the Adirondack strongman, as almost any fighter would have been. Even Jimmy Young, a former champion, was no match for the young assassin. And the aging Young cost D’Amato $600 for a week’s work.

Cus did obtain the services of one world class boxer for a few days when WBC cruiserweight champion Carlos De Leon returned to Catskill. Six minutes in the ring with the classy De Leon made Mike realize what it was like to fight a real pro. De Leon took young Tyson to school so to speak, but Mike learned his lessons quickly. He marveled at De Leon’s ring savvy and relished the mental exercise of trying to out-think his crafty foe. Mike made his share of amateurish mistakes, but he was never guilty of the same mistake twice. Cus D’Amato, his astute trainer, was in his usual position on the ring apron, studying his young phenom very carefully and yelling occasional instructions to him in an attempt to eliminate his bad habits. “Don’t be stationary. Keep moving your head. And keep your hands up.”

Another capable sparring partner followed De Leon into town. Tyrone Armstrong, the Philadelphia strongboy, returned after completing a sparring session with Pinklon Thomas. Armstrong boxed three rounds with Tyson and came away highly impressed. “The boy hits real hard, harder than Thomas. He has great balance and leverage, that’s why his punches hurt so much. I haven’t seen anybody in the division that can beat him.” Jacobs and D’Amato continued to search for a capable opponent for Mike’s professional debut, without success. They did locate a promoter, however, Tri-State Promotions, under the guidance of Lorraine Miller. Mrs. Miller immediately scheduled a press conference in Latham, New York, to introduce Mike Tyson to the Albany media representatives and announce the details of his first fight.

We have worked hard to put on good shows in the Albany area, and we are proud to be able to promote Mike Tyson’s professional debut. The fight will be held In the Albany Convention Center at 8 p.m. on the night of March 6 against an opponent to be named later. Believe it or not, it’s very hard to get an opponent for Mike. Most managers have heard about Mike’s success in the amateurs and they don’t want any part of him. We’re hopeful we can get the proper opponent, but we’ll be thankful to get an opponent period.

Mike Tyson, who sat quietly during the proceedings, was matter-of-fact about his ring potential. “I have all the confidence in the world in my managers. I fight whoever they tell me. If they know I can beat the man, then I know I can beat the man too.” Assistant trainer Kevin Rooney assured the press that his charge was ready for a tough struggle. “Cus D’Amato is a great manager. He wants an opponent for Mike who will come to fight. Mike needs strong opponents in order to develop. If his opponent is a bum, everyone gets cheated, and Mike gets cheated. We are looking forward to a tough match.”3

Within a week, a suitable opponent had been signed to a contract. He was a 19-year-old Puerto Rican named Hector Mercedes, another recent entrant into the professional ranks. Mercedes, whose 0–2–1 record seemed made to order for the ambitious Tyson, had the reputation of being a tough kid. He had compiled an impressive amateur record around his hometown of Rio Piedra, but he had never fought anyone of Tyson’s caliber. Cus knew the kid was a mixer, but he was bothered by Mercedes’ lack of height. Although Hector weighed a solid 204 pounds, he stood only 5'7' tall, and Mike would tower over him in the ring. Cus realized that, if Mike beat Mercedes badly, the crowd would think of him as a bully picking on little guys. Cus tried to rationalize the selection of Mercedes for his own piece of mind.

Just the fact that Art Romalla [Mercedes’ manager] even lets him get into the ring with Mike shows that he isn’t gonna be a pushover. I like that. It wouldn’t do Mike any good to fight a bum. Newspapers make a big thing out of height and reach, but that stuff really isn’t relevant. Timing is the factor. We’ve taught Mike from the start to get away from punches. He’s quick with the fists too. Mike’s elusive yet powerful. And if he delivers that exceptional punching power with either hand, he’s unstoppable. In many ways, Mike reminds me of Jack Dempsey, the “tiger of the ring.” He has Dempsey’s ferocious attack. But he’s also more of an individual with a style and punch all his own.4

Lorraine Miller promoted 15 Tyson fights, including his pro debut. Before the Mercedes match, Miller showed some posters to D’Amato, who growled, “Tyson’s picture’s too small,” so Miller immediately ordered new posters and used her stack of 300 original posters to kindle firewood. In later years, she received calls from memorabilia buffs offering up to $1,000 per poster. “You live and learn,” she sighed.5

Back in the gym again, Tyson put the finishing touches on his conditioning program. He sparred with a young fighter named Charles Thurman, an amateur who was training for the finals of the New York State Golden Gloves Tournament. Thurman caved in quickly under Tyson’s constant barrage, however, calling it quits midway through the second round. Even as his career became a major focal point in his life, Mike Tyson still found time to work out with the younger members of the Catskill Boxing Club. He could often be found instructing kids like Frank Houghtaling in the proper use of the heavy bag. Houghtaling, an 11-year-old miniature bulldog, was just about ready to embark upon his own amateur adventure. He idolized Mike as did most of the other street urchins who frequented the dingy gym over the police station. Mike responded to their attention by becoming a role model for them. He wanted to give something back to the gym that spawned him and to the kids who would follow him.

Suddenly it was March 6, and the moment of truth had arrived. The final countdown began at approximately 5:30 p.m. as the light-colored station wagon pulled away from the old homestead, its headlights searching for a path through the late winter darkness. The rapid acceleration of rear wheel against gravel road sent clouds of brown dirt billowing skyward as Don Shanagher pulled out onto Route 385 with his entourage of Cus D’Amato, Mike Tyson, and Kevin Rooney. Within minutes they were on the New York Thruway headed north for Albany, for the Convention Center, and for Tyson’s appointment with destiny. Mike walked through the front door of the Albany Convention Center unnoticed at about 6:30 wearing an old, beat-up brown leather jacket and carrying a cloth gym bag. He immediately headed to the locker room to get himself mentally prepared for the conflict ahead. That in itself was a major feat because the locker room in the Convention Center was also the men’s lavatory. The small, cramped room had been outfitted with temporary lockers and benches to accommodate the boxers, but it was still open to the public, so the fighters constantly had to sidestep onrushing male patrons in need of the facilities.

Outside the arena, several hundred early arrivals, unaware that they were about to witness history in the making, milled about drinking beer and scarfing down hot dogs. Some of them tried to kill time by watching the inept performances in the ring. These preliminary fighters were, in general, a sad and often tragic lot. They sweated and bled and risked their health for pennies. The four-round prelim boys made about $250, out of which they had to pay their expenses, such as equipment, trainer’s fees, and manager’s fees. If they ended up with $50 for themselves, they were lucky. Six-round fighters pulled in $350, and eight-round boys drew the exorbitant sum of $750. Ninety-nine percent of these club fighters would wind up broke, many of them punchy. Most club fighters never even knew the names of the men who taped their hands before the fight. Fewer than one percent of them escaped from the hellholes of the small, smoke-filled arenas and went on to a successful career in the ring. Mike Tyson would be one of the lucky ones.

The old man stood in the dressing room and watched his kid warm up, watched him wheel around the room in time with the music. Lovergirl, Square Biz, the pop-soul sound of Teena Marie was little more than white noise in the old man’s head, which was teeming with other themes. At 6 feet and 212 pounds, the kid was an impressive physical specimen. Plus, as the veteran pugs liked to say, he carried a cure for insomnia in either hand.6

Cus talked to him incessantly, reminding him about the need to control his fear, remain calm, and be aggressive. “Remember what I taught you. If you do everything you learned in the gym, you will win.” Mike dropped down on the hard wooden bench and began lacing up his shoes as fight time drew near. At 7:40, assistant trainer Matt Baranski came over to help Mike adjust his protective belt, and a few minutes later Cus eased down on the bench next to his edgy fighter and began wrapping his valuable hands with gauze, 18 feet of soft, white gauze. Cus then applied a few strips of tape to each hand, being careful not to let the tape get over Mike’s knuckles, a practice that was frowned upon by the State Boxing Commission. When the taping process was completed, Mike clenched his hands into fists, making sure they felt comfortable and were well protected. Now the young warrior was ready to go. He rose slowly from the bench and flexed his muscles, then returned to his shadow boxing to keep warm. He was attired in white trunks and black shoes, no socks, no robe, no flashy accouterments, just the bare essentials. Tyson said it made him feel more like a gladiator to be dressed like this, remembering that the combatants in ancient Roman gladiatorial battles entered the Coliseum clothed only in loin cloths and sandals.

It was now only minutes to fight time, and the locker room reverberated with the blare of rock music as Tyson increased the intensity of his warm-up routine in an effort to get himself well loosened up before heading for the ring. He was bobbing and weaving, slipping imaginary punches, and occasionally shooting out sharp jabs with his left hand to the face of an invisible foe. Sometimes the jab was followed by more bobbing and weaving. Other times it was a prelude to a two-fisted attack. Perspiration dripped freely from the shoulders and neck of the Catskill warrior, and his bronze physique shimmered like a Greek statue in the smoky haze of the locker room/lavatory. Suddenly the door opened and a wizened head peered in, a cigarette butt protruding from between two rows of rotten teeth. “They’re ready for you now.” Cus cast a concerned glance at his restless fighter and gently patted him on the shoulder. “Okay, let’s go, Mike.” The parade left the locker room and headed for the ring, assistant trainer Matt Baranski in the lead, followed by Tyson and Cus D’Amato. Jimmy Jacobs, D’Amato’s partner and co-manager, lagged behind to view the proceedings from the top of the steps, wondering what the fates had in store for his boy. Jacobs felt good about things in general. The preparation had been intense and thorough. Mike Tyson had been preparing for this night for five years, and he would be a power to be reckoned with in the heavyweight division, if Jacobs and D’Amato were any judges of people. Tyson was an impressive talent, and Jacobs was getting positive vibes about the entire venture. He was confident that the venture would be successful.

Baranski lifted the second strand of rope and Mike Tyson slipped deftly into the ring to a loud round of applause. Even though this was Mike’s first pro fight, he was well known around the Albany area thanks to his exciting amateur career. His popularity was such that the Convention Center was almost filled with over 2,500 Tyson fans in attendance, all of them thirsting for blood. Hector Mercedes, attired in red trunks with a white stripe, waited in the ring. He eyed Tyson curiously, wondering why everyone was making such a fuss over a big kid with no pro fights under his belt. Mike Tyson had come a long way in the past four years, both technically and emotionally. He was no longer the excitable kid who rolled around the ring ecstatically in Colorado Springs after a winning effort. He had matured considerably, but he was, after all, still only 18 years old and just a boy, albeit a boy in a man’s body. Mike could feel the butterflies squirming deep within, and his stomach muscles were knotted up with the tension of the moment. He stood in his corner anxiously waiting for the start of festivities.

As the fighters moved to the center of the ring to receive the referee’s instructions, Channel 10 News in Albany, New York, was there to record the historic event. Mercedes’ 5'7" stature made him seem much shorter than the solidly built Tyson. The two men shook hands and returned to their respective corners to await the bell. Tyson was edgy and impatient. At the sound of the bell, he sprang straight at Mercedes, driving the little man to the ropes. He flailed away viciously with both hands, reminiscent of his first “smoker” four years before. The unexpected activity in the ring brought oohs and aahs from the crowd. Two men who were catching a few winks in the front row suddenly bolted upright and directed their attention to the ferocity above them. Several stragglers, on their way to the concession stand, turned back to watch the action. Tyson was a good student and had mastered his lessons well. He remembered D’Amato’s instructions—the floating rib on the left side and the liver on the right side. A sharp left crashed against Mercedes’ liver, and two pulverizing rights found the targeted rib cage. Mercedes winced in obvious discomfort and tried to cover up. Tyson backed off momentarily and then came back with a right uppercut that straightened the Puerto Rican up like a pole. One last left hook dug deep into Mercedes’ side. All the air seemed to leave his body with a hiss as he sank to one knee in the corner. The referee stopped the fight at 1:47 of round one. It was an electrifying start to Mike Tyson’s career, and it brought the crowd to their feet, cheering and screaming. Mike Tyson would give them more of the same in the months to come, much more. But for now, the battle was over and the young gladiator basked in the glory of his first professional victory. When asked about his strategy for the fight, Tyson replied, “I just wanted to throw a lot of punches to confuse him.” Obviously the strategy worked.

Cus was pleased with his boy’s initial showing and couldn’t resist gloating a little bit. “He looked good, didn’t he?” The old man’s eyes twinkled as he thought about it. Jim Jacobs was also impressed by what he saw in the ring. “The other fellow fought back. He threw good punches. If Mike wasn’t so elusive, he would have got hit. Prior to this fight I thought Mike was a spectacular fighter. Nothing that happened tonight altered my feeling. Mike is an irresistible force.” Cus nodded in agreement. “Mike was at a disadvantage in the amateurs. For example, if he knocked someone down in the amateurs, the opponent would take a nine count, then could get even in the scoring by landing a punch, though not nearly so damaging. The professional ranks are marvelous for Mike. They score for aggressiveness. I expect Mike to break Patterson’s record.” Tyson echoed his manager’s optimism. “I fought all the best fighters in the world as an amateur. I fought the better fighters at a younger age. I have reason to be confident.”7

Another D’Amato boxer fought on the same card. Former junior welterweight contender Kevin Rooney decisioned Garland Wright over the eight-round distance. Rooney had been a fighter on the way up until 1981, when he lost a nationally televised fight to Davey Moore. One year later, Rooney was decisively knocked out in the second round by Alexis Arguello, again on national TV. Now 29 years old, he was no longer a contender although his 20–3–1 record was still an impressive credential. If he wanted to, Rooney could probably have prolonged his pugilistic career for another half-dozen years, although he most likely would have been an “opponent,” a stepping stone, rather than a contender. At Cus D’Amato’s urging, Kevin Rooney chose another path to the top of the fight game. He was learning to be a boxing trainer and, with D’Amato to teach him, he had the greatest instructor in the world.

That Cus D’Amato was the ultimate trainer was no secret. His discovery of a new heavyweight sensation had been discussed in boxing circles for several years. No fighter in the country could entice 2,500 people to witness his pro debut with ringside tickets selling for $12.50 a pop. No fighter in the country could command $500 as a four-round neophyte with no pro record. Mike Tyson could. And Cus D’Amato was the reason. Even the news media was aware of the monumental story that was unfolding in the tiny hamlet of Catskill, New York. People Weekly magazine was the first of the popular pulps to jump on the bandwagon. They sent a reporter to D’Amato’s home town to spend several days with him and his young protégé prior to the Mercedes fight, to document the resurrection of the grizzled old manager, and to introduce his new heavyweight contender to Mr. and Mrs. America. Fortunately for everyone concerned, the public’s first glimpse of Mike Tyson was an awesome one. He left Hector Mercedes in a bloody heap in less than two minutes. The Ewald household celebrated Mike’s victory with a lot of noise and raucous laughter into the wee hours of the morning. It was a moment to cherish and remember on the banks of the Hudson. Cus D’Amato, however, was more restrained than the rest of the family. He realized that Mike was still essentially an undeveloped raw talent. A tremendous amount of work remained if Mike Tyson was to become a world-class fighter capable of winning the championship before he was 22 years old.

The next morning at breakfast, the cagey old trainer brought his charge back to the real world. Tyson was still on cloud nine after his short and explosive night’s work. His decisive victory made him feel invincible, but Cus soon made him face the reality of the situation.

Feelin’ pretty cocky, huh? Think you’re tough, don’t ya? Unbeatable. Well let me tell you, you’re not. Oh, you did good all right, and you deserved the quick knockout, but you made a lotta mistakes too. If you had fought an experienced fighter last night, he woulda killed you. You were too excitable, too wild. You fought out of control. A good fighter would have laid back and picked you apart. You’ve got to stay calm so you can think out there. Champions are always calm. And that’s what you’ve gotta learn. You did a good job in your first fight, but now we’ve got to go back to the gym and work on your ring discipline.

These morning-after-the-night-before discussions were to become a regular part of Mike Tyson’s boxing regimen, and a part that he always dreaded. No matter how good he would do in a fight, Cus would always find some mistakes he had made. Cus wanted to drill into Mike’s mind the fact that he would never be perfect, could never be perfect. He wanted Mike to realize that no one is perfect. No one should ever get cocky and think they are invincible. There is always something more that can be learned. When a person stops learning and begins to believe that he is unbeatable, that’s when he becomes vulnerable. Cus wanted to perpetuate the drive and the desire in Mike Tyson. He wanted Mike to be constantly stretching for that unobtainable goal—perfection. In that way, and only in that way, could Mike maintain his equilibrium in the face of success. And only by striving for higher and higher goals could he hope to win the championship and, having won it, hope to hold it over a long period of time against younger and hungrier fighters.

After a couple of days of rest and relaxation, it was back to the gym once more, back to Cus D’Amato’s school of mental alertness and pugilistic excellence. Now that Mike had one pro bout under his belt, Cus was ready to unveil his newest stratagem. He would make Mike Tyson the busiest fighter in the United States, with a scheduled match every two weeks. Cus believed that the old fighters had the right idea; you had to fight often to stay on top of your game. The more you fought, the better you got. The great fighters of yesteryear, men like “Sugar Ray” Robinson, Archie Moore, and Willie Pep, all had over 200 professional fights before they hung up the gloves for good. Cus had a dream, to make Mike Tyson the youngest heavyweight champion in history, and to accomplish that feat, he decided to spoon-feed the young lion with a non-stop diet of boxing matches in order to force his protégé to develop his almost unlimited talents faster than anyone ever had before.

Tyson acquired a new sparring partner in mid–March, Delen Parsley of New York City. Parsley was another street kid who had the heart of a lion. Tyson was a very aggressive fighter, but he found out soon enough that Parsley was also an aggressive fighter who kept coming in all the time, taking two punches and giving two in return. Or trying to. Cus emphasized defense, and he taught Mike all the cute moves. “Keep movin’ all the time. Don’t stand in front of him. Move to the side. You can hit him from the side but he can’t hit you. It’s the perfect place to be. You gotta be elusive.” Cus was thrilled to have Parsley working with Mike. “He’s givin’ Mike exactly what he needs. He’s tough. He takes a good punch and keeps comin’. I wish he had been working with us for months.” Unfortunately, Parsley ran out of gas in a hurry. He had the heart, but Tyson had the ammunition. Mike was just too strong for him and, after taking a few thousand blows to the liver and kidneys, Parsley was forced to throw up the white flag and go back to the city.

Mike’s second fight arrived in the blink of an eye, only 35 days after his first fight. It was once again held in the Convention Center in Albany, the second of three fights contracted for with Tri-State Promotions. The opponent was a tall black man named Trent Singleton, and if you bent down to tie your shoelace after the fight started, you might not have seen Singleton in action at all. When the bell sounded for round one, Singleton threw a feeble left in Tyson’s direction, but Mike slipped it easily. That was it as far as Singleton’s offense was concerned. Mike countered with a hard left that put Singleton on the seat of his pants with a surprised look on his face. A flurry of rights and lefts by the excited Catskill bomber dropped Singleton twice more in less than a whisper, automatically stopping the fight. It had lasted only 57 seconds, hardly time enough for Tyson to work up a sweat. He had a tougher workout in the locker room before coming to the ring. During the interview session after the fight, one of the reporters congratulated D’Amato. “Well Cus, you’re a success.” That statement caused the old trainer to deliver a little more D’Amato philosophy.

I’m not a success yet. And neither is Mike. When these kids reach the point where they become champion, everybody thinks they’re successful, they reached the top. They think I’m successful because I managed the champ. But I’m not. I don’t succeed unless I make that man completely independent. How do I do that? Well, when he gets the feelin’ that he doesn’t need me anymore, which is terrible for fight managers, then he’ll leave me. They don’t need you anymore. They don’t wanna pay, but you see I don’t think I’m successful unless I’m able to do this. When I make him completely independent of me, then I have succeeded. Now if he succeeds before I do this, then he’s successful but I’m not.8

Five days after Tyson’s second victory, one of the great middleweight fights of all time took place in Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, Nevada, before a sellout crowd of 15,008. “Marvelous” Marvin Hagler, a future ring immortal, defended his title against Thomas “The Hit Man” Hearns, one of the hardest punchers in the game. The action was fast and furious from the outset as Hearns was determined to establish his dominance over the champion. The effort might have been successful against a lesser man, but not against a brawler of Hagler’s magnitude. The two fighters stood toe to toe for three full minutes, taking turns knocking each other’s head off. Hagler staggered Hearns just before the end of round one, turning “The Hit Man’s” legs to jelly. The champion, in return, had received a vicious gash over his right eye, and it bled profusely for the rest of the fight. At one point in round three, it looked as if referee Richard Steele might stop the fight because of the cut and award the decision to Hearns. The fight was interrupted briefly to allow the ring doctor to examine the wound and, when he motioned the fight to continue, it spelled the beginning of the end for Hearns. Hagler attacked with a purpose, and within 45 seconds he landed a right hand that sent Hearns spinning backwards against the ropes. Hagler was on him like a big cat, and a barrage of punches sent “The Hit Man” to the floor for a full count. The battle, which will go down in history as one of the epics of the ring, lasted 8:01. Mike Tyson watched the fight on closed circuit television with considerable interest. Mike was an avid student of the sport, and he studied every match carefully, always analyzing, always learning. He learned a lot about heart during that fight, from both corners.

As Mike’s professional career was launched, his personal life started to settle down and gain stability. He felt more comfortable now around Cus and Camille, and he began to consider them family rather than acquaintances. The time spent with Cus grew into a true father-son relationship instead of a trainer-fighter relationship. Camille became someone that Mike could go to with his problems and with his doubts, someone from whom he could receive the solace that he so desperately needed. Ewald House had grown into a home for Mike Tyson during the spring of 1985. It was no longer just a place to live.

The boredom and drudgery of Cus D’Amato’s intense training program continued through April, and more sparring partners fell by the wayside. By the end of the year, Mike Tyson would destroy 40 sparring partners in just 52 weeks. No one could be found who could stand up to his devastating punishment for more than a week or two. Otis Bates of Denver, Colorado, was a typical Tyson opponent. Bates contracted to spar with Tyson for a week, and he arrived in Catskill in mid–April, full of determination and enthusiasm. He had sparred with the likes of Carl “The Truth” Williams and Larry Holmes, and he was looking forward to tangling with New York’s bad boy. It was a mistake that he quickly paid for. Mike punished him so thoroughly in only two days that he called it quits and headed home. Cus just shrugged his shoulders in bewilderment. “Mike’s opponents are not bums. He hits them quickly and they go. I can’t even get him opponents for regular fights. Once a month is not enough. I’d fight him every week if I could find someone to take him on.”

At one point, Tyson was forced to go five weeks without sparring due to a lack of willing volunteers. Finally, on the same day that Tyson learned the identity of his next opponent, a new sparring partner arrived on the scene. His name was Tom Sullivan, a native of Indiana and a veteran of 29 professional fights. It would be Sullivan’s job to get Mike ready to mix it up with Don Halpin, a journeyman fighter from Massachusetts. Halpin, with an undistinguished record of 9–17, had the reputation of being a survivor, a gutty kid who could give an opponent a hard time and take a fight to its completion. Kevin Rooney was familiar with Halpin’s record. “He’s been around. He’s an old war-horse. He looks to be an experienced fighter.” It was obvious that Rooney was anticipating a tough struggle for his boy, one that Tyson badly needed. You don’t learn much from fighting pushovers. Don Halpin had been in the ring with some proven adversaries. In 1981, he had lost an eight-round decision to Tony Tubbs, and in 1983 he was beaten by Jimmy Young. He was considered to be the type of fighter who lived by his wits and his toughness. You had to beat Halpin. He wouldn’t quit on you.

As the weeks passed, Mike Tyson seemed to have taken on a new, calmer approach to the ring wars. Cus credited this change in attitude to his sparring partner, Tom Sullivan. “Sullivan fought back and didn’t crumble when Mike hit him, so Mike was forced to settle down and figure out what he wanted to do. He couldn’t just go in swingin’ without a battle plan.” Cus was so impressed with Sullivan’s contribution to Tyson’s preparedness that he gave the fighter a sizeable bonus, hoping to entice him back another time. May started off in grand fashion around the Catskill Boxing Club. On the tenth of the month, Cus D’Amato was honored by his peers in the boxing world. During the World Boxer Day celebration in Madison Square Garden, Cus was presented with the Joe Louis Award for his contributions to the sport. It was only fitting that the award should be presented in the Garden, since this had been the stronghold of Cus’s enemies in the infamous IBC and its mastermind, James D. Norris, Jr.

Ten days later, on May 20, heavyweight champion Larry Holmes pulled out a close decision over Carl “The Truth” Williams in Reno, Nevada, to retain his IBF crown. As it turned out, the fight was decided strictly on heart. It was a perfect demonstration of how to separate the men from the boys. After ten grueling rounds, Williams was comfortably ahead on all scorecards and was well on his way to dethroning the pride of Easton, Pennsylvania. It was obvious in the corners between rounds ten and 11 that both fighters were suffering from extreme exhaustion. Tragically, Carl Williams was not able to rise to the occasion. Even with the title in his grasp, the younger fighter could not draw on the necessary reserves to put out a maximum effort during the final five rounds. Larry Holmes, on the other hand, realizing what was required to win the fight, picked himself up by his bootstraps and outpunched his younger foe in rounds 11 through 15. On this night, Larry Holmes showed the boxing world what it takes to be a champion. His gritty performance did not go unnoticed in the Tyson camp. Mike quickly made a mental note of the achievement, particularly since it verified one of Cus’s favorite doctrines: “When you’re watchin’ a fight, you’re watchin’ more a contest of will than of skill, with the skill prevailing only when the will is not tested.”

The day before the Halpin fight, another local press conference was held to stimulate interest in the event. During the question and answer period, one of the Channel 10 reporters noted that Halpin hadn’t fought in over 13 months, but Halpin shrugged off any inference that the inactivity might affect his performance. “I haven’t been the most active fighter in terms of bouts per year, but the time off has never hurt before. I’ve always come back strong.” Tyson was more relaxed at the press conference this time, and he exuded an air of increased confidence now that he had two pro fights under his belt. “I’m sure of a victory. If it goes six rounds, I’ll beat him in six rounds and look good doing it. Whatever it takes is what I try to do. I’m sure the fans will enjoy the fight. I feel real good.” One of the reporters cautioned Mike about what a tough guy his new opponent was. Mike just shrugged and in typical D’Amato style mumbled, “Yeah? I’m a tough fighter too. And I move my head and he doesn’t.” When Mike Tyson’s quotes appeared in print, he often sounded like a braggart, but he wasn’t. He was quiet and polite, but he was confident—very, very confident.9

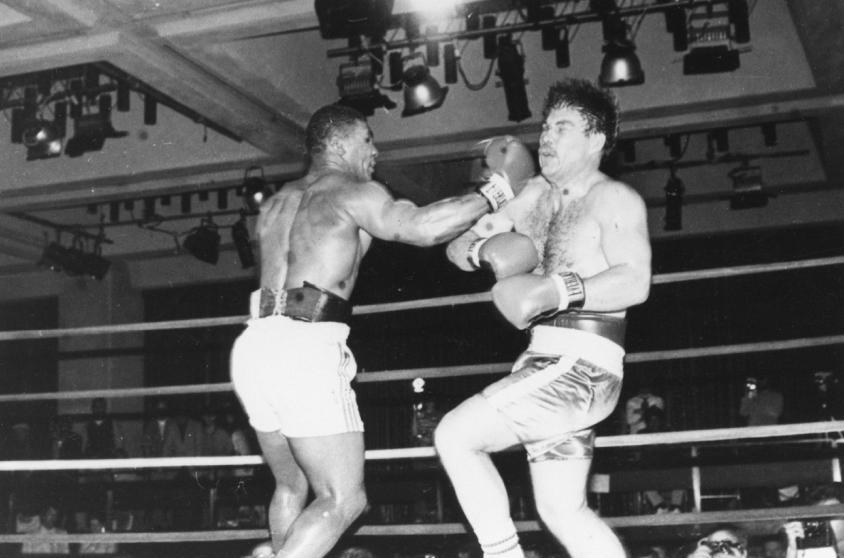

Tyson and Halpin with Cus D’Amato at the weigh-in for their May 5, 1985, match (courtesy Paul V. Post).

Tyson arrived at the Convention Center on the night of the fight still unnoticed by the general public, but that comfortable situation was destined to change quickly. Within a few months his face would become familiar to most boxing fans thanks to a massive publicity campaign masterminded by his managers. But in May of 1985 he could still walk the streets without being recognized. He had increased the number of people in his unofficial retinue since his last visit to Albany however. Not only was he accompanied into the arena by his three trainers, but he was also followed in by two admiring blondes. After his usual warm-up period in the locker room, Mike headed to the ring decked out in white trunks and white shoes. Halpin was waiting for him, anxious to get it on. The Catskill teenager was also anxious, but he fought under more control in this fight than he did in the first two. He seemed to be maturing a little bit more with each passing month.

As round one got under way, it was apparent that Mike respected Halpin’s ring experience and his reputation as a scrapper. He didn’t rush across the ring to meet his foe as he had in his previous two fights. This time he approached his man cautiously and tried to follow Cus’s pre-fight plan. Cus wanted Mike to work his man inside with an intense body attack in order to open him up so he could get a clean shot at his chin. Mike followed Cus’s instructions to the letter. In round two, he kept boring in, punishing Halpin to the body. In round three he suddenly switched his attack to the head and brought the crowd to its feet with a sharp left to the side of Halpin’s face followed by a sizzling right to the cheekbone. These punches signaled the beginning of the end for the Massachusetts fighter. Although Halpin survived the round, the success that Mike had in getting through his guard only served to increase his confidence level. If there was one thing that Mike didn’t need, it was more confidence. He rushed out of his corner in round four, looking for the knockout. A flurry of punches put Halpin in immediate trouble, and a dynamite left hand sent him to the canvas for an eight count. As soon as the referee waved the two fighters together, Tyson was back on the attack. In center ring, the Catskill Clubber caught his man with a right cross, staggering him. A left broke through Halpin’s guard once again, and a follow-up left sent the Irishman reeling backward across the ring. Mike ran after his man and landed a paralyzing right uppercut that snapped Halpin’s head back violently as he collapsed into the ropes. The Boston fighter bounced off the ropes, landing face-first on the floor, where he lay motionless for five minutes. The referee finished the count of ten at precisely 1:06, but he might just as well have counted to a thousand. Halpin didn’t hear a thing.

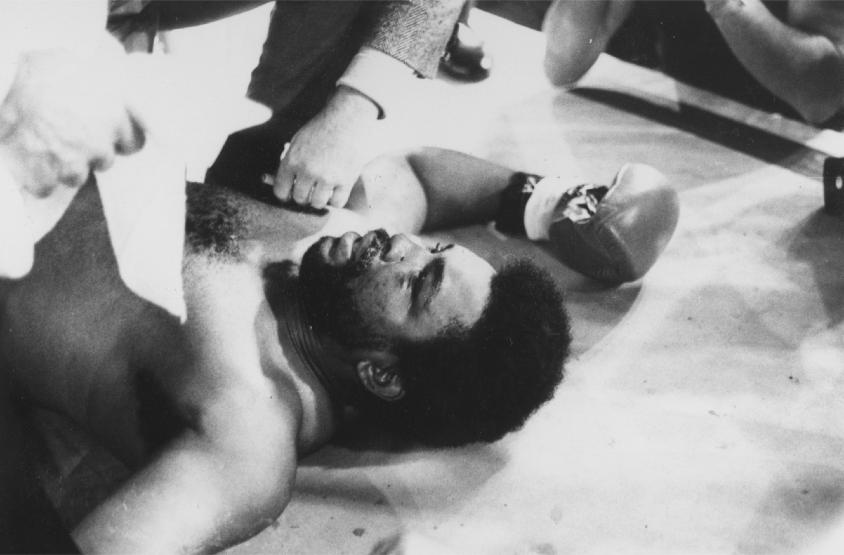

Tyson knocked out Don Halpin at 1:04 of round 4 (courtesy Paul V. Post).

Mike Tyson was an enigma in the violent world of boxing. He was one of the most vicious punchers in the ring, yet he also had a gentle side to his nature. After every knockout, he was more concerned with the welfare of his opponent than he was with the victory. Mike couldn’t relax in his corner until he saw Halpin assisted to a stool that had been brought to center ring. Mike was at his side immediately, giving his opponent a loving hug and whispering words of consolation in his ear. It is doubtful that the bewildered Halpin heard Mike’s words of sympathy. He was still dazed when his handlers led him back to the locker room and laid him on the examining table. The doctor immediately set about to restore his broken features, no mean feat when you realize it took 29 stitches to close the cuts on his face and a splint to straighten out his broken nose. Forty-five minutes after being knocked senseless, the battered Irishman dragged himself off the table, packed his bag, and went home. He would live to fight another day, but he chose not to. Don Halpin retired from the ring that very night.

It was too late for an 18-year-old to go out on the town to celebrate his victory, so Mike Tyson accompanied his trainers back to Catskill and enjoyed a quiet snack with Cus and Camille. The next night was different, however. Mike and his buddies peeled rubber up the New York Thruway to Crossgates Mall, a large, enclosed promenade five miles west of Albany. Over 150 concerns filled the two square mile complex, including a fine selection of clothing stores, jewelry stores, and restaurants (both quality and fast food), plus 12 movie theatres. The first stop of the night for the Tyson band was Ben & Jerry’s, where the boys gorged themselves on homemade ice cream. After a boisterous 30 or 40 minutes reliving the glory of the night before and checking out all the girls in tight jeans, Mike and his crew jumped the escalator for the third floor where their favorite actor, Eddie Murphy, was cavorting across the screen in a wacky comedy, Beverly Hills Cop. By the time the movie ended, the gang was ready to eat again, so they fought their way down the ”up” escalator to McDonald’s on the floor below. Mike happily pigged out on Big Macs, fries, and Sprites. He was in heaven knowing that he could eat anything he wanted for two whole days, but he also realized that come Tuesday morning, he would pay dearly for it. Cus would make him toe the mark then, and would make him work twice as hard to take off the extra weight that resulted from his gluttony. But that was two days away. For now, it was just eat, drink, and be merry.10

Tom Sullivan was back in Catskill to work with Tyson once again. It was brutal work but the hours were good and the pay was excellent. The happy Hoosier had considerable experience sparring with Jerry Cooney and Carl Williams amongst others, but he had never been in the ring with anything like the kid from Catskill. “He’s a much harder puncher than any of the other heavyweights. And he’s relentless. There’s no stopping him.” After one of the sparring sessions, Mike took Sullivan back to Ewald House and introduced him to Camille. “I want you to meet my mother.” Camille laughs at the memory. “I thought that kid’s eyes would pop from his head when he saw my white skin.”11 From Mike’s standpoint, it was just one more sign that he had finally settled into his new life and had accepted Cus and Camille as his family. Several weeks later, the former juvenile delinquent surprised his adopted mother with her first Mother’s Day card. Mike wrote on it, “For someone I love, and wish you was my mother. Happy Mother’s Day and I love you. By Michael, your black son.” Not only was Mike becoming part of the family now, but he was also becoming financially independent, thanks to his earnings in the ring. After watching this situation develop for several months, Cus decided that Mike had earned the right to more individual freedom and responsibility.12

The Catskill teenager had wanted to build a pigeon coop in the front yard of the Ewald house for several years. Now, with Cus’s blessing and Camille’s permission, the youngster was given the go-ahead. He quickly recruited several of his buddies and, with their help and an ample supply of plywood and chicken wire, he constructed a small wooden structure along the banks of the Hudson. As soon as he had hammered in the final nail, the boyish Tyson set out to stock the coop with a large family of his cherished “street rats.” It was a happy day for him when he placed the first pigeon in its new plywood home. At long last, he had everything he wanted. He was part of a loving family. He was being given the responsibility due an adult. And he had a new family of “babies” to take care of, his first flock in over five years. It was a great feeling just to be alive. The same week, the “new” Tyson stopped at Bob Meo’s barber shop and had his hair redesigned. Mike always wore his hair close-cropped but, on this occasion, he took it one step further and shaved it clean all around about two inches above the ears, giving the impression that someone had covered his head with a soup bowl and then took a razor to it.

As the days passed, Mike was forced to step up his pace in the gym. With his next fight less than a month away, June 20 to be exact, he had to get in peak condition quickly and stay there. His new schedule consisted of a five-mile, early morning run, two hours of gym work, and four or five rounds of sparring. And it was relentless, every day, seven days a week. There was no relief in sight for a young man who was aiming for the stars. Cus, Jacobs, and Cayton met in New York City in late May and decided to make a change in promoters. Tri-State Promotions had been unable to provide the kind of publicity that Tyson’s management committee felt was necessary in order to properly promote their “product.” Therefore, Bob Arum, one of the top promoters in the country, was brought into the picture and took over the arrangements for Tyson’s upcoming fight. He immediately scheduled it for the Resorts International Hotel in Atlantic City, on the undercard of the nationally televised Jesse Ferguson-Tony Anthony bout. It was even possible that Mike could get some television exposure if the main event ended in a quick KO. Some people in the Tyson camp were not too thrilled to learn that Bob Arum would be the promoter. His reputation was not exactly untarnished around the boxing world. Arum, a 52-year-old New Yorker, had been schooled as a lawyer at Harvard University, but a subsequent business project for the Internal Revenue Service soon convinced him that an enterprising young man could make big money promoting prize fights.

Bob Arum was a workaholic and for several years spent every waking hour negotiating with a multitude of managers and fighters to promote their bouts. His big break came in 1962 when he became acquainted with Muhammad Ali—then Cassius Clay—and started to promote Ali’s fights. After Ali was stripped of his title for refusing to fight in Vietnam, Arum arranged a deal with the WBA and ABC-TV to promote an elimination series to find a worthy successor to Ali. Over the years Bob Arum’s power has grown, but many people in boxing’s inner circle have come to despise him. He has been labeled as a liar, a cheat, and a double-crosser, yet fight managers still deal with him. That’s the way it is in boxing, even today. The man with the best deal gets the match. Period.

As the days wound down, concern grew in the Tyson camp over the condition of Mike’s left hand, the same hand he injured in Finland. The hand throbbed constantly, and Cus was afraid that Mike had incurred more ligament damage. After a thorough medical examination, however, the considered opinion of the doctors was that nothing could be done to restore Tyson’s hand to normal. They said it was one of the hazards of boxing, a condition that he would have to live with as long as he put on the gloves. Cus began covering the last two knuckles of Mike’s hand with a sponge during the sparring sessions to protect it as best he could, but on fight night the sponge would come off and Tyson would have to endure the pain in silence. Sunday, June 16, was a special day in the life of Cus D’Amato. It was Father’s Day and, on that day, Mike Tyson presented him with a Father’s Day card, the first time that Mike had ever done that. Cus was truly touched, and it was something that he would always remember with misty eyes. Cus never married, but on this day he became a father.

Two days later, Kevin Rooney packed the station wagon with the necessary boxing gear, and the four-man crew set out for Atlantic City, a five-hour drive. They found things in turmoil when they arrived at the seaside resort. Mike’s opponent had run out on the bout and with the fight less than 48 hours away, they needed an opponent quickly. The unlucky volunteer turned out to be Ricardo Spain, small for a heavyweight at 184 pounds, but aggressive and hungry, and better still—available. Cus was once again concerned about the small size of Mike’s opponent, but Spain was very strong in the upper body. His thin legs accounted for most of the lack of weight, and Cus figured that Spain would come into the ring and run in order to survive a few rounds. How wrong he was.

The Tyson-Spain fight was the first bout on the card. Spain surprised everyone by coming right at Tyson, who met him in center ring. The tiny heavyweight threw the first punch, a left hook, but Tyson moved his head ever so slightly and slipped it easily. Then the Catskill Clubber began his own offensive. A thundering overhand right found its mark on the side of Spain’s head, stunning the smaller fighter. He fell forward into Tyson, then collapsed backwards to the floor. Although dazed and hurt, the gutsy little fighter dragged himself to his feet, barely beating the ten count. Tyson was right back on the attack, backing his man into a corner where he unleashed a barrage of short, powerful, punches. The kid from Catskill threw a left, blocked a right, and then countered with a thundering right hand that snapped Spain’s head back. A pawing left, another hard right, and still another right crashed against Ricky Spain’s face. The referee jumped in as Spain’s knees sagged, and he caught the stricken fighter before he could fall. It was Mike’s quickest knockout yet, with only 38 ticks off the clock.

The Tyson team was very upbeat after the fight, as you would expect. Cus D’Amato was beginning to beat the drum for his rapidly improving fighter. “He has great potential. Outside of Larry Holmes, the heavyweight contenders are a mediocre lot. Pinklon Thomas is probably the best of the lot, but the best fighters are the ones who are up and coming—Tyson, Henry Tillman, Tyrell Biggs.” Rooney was so excited about the quickness of the knockout that he could hardly contain himself. “He’s ready to step out. He’s beginning to do things instinctively. We’re going to fight again down here.” When Tyson was asked how he liked fighting in Atlantic City, he just shrugged his shoulders. “No big deal. I feel more at home fightin’ out of town. I fought all over the world in the amateurs. When I fought in Albany that was the first time I ever fought in my own area.” Bob Arum crashed the scene and moved around the locker room yelling, “He looked awesome, awesome!” But it was left for former middleweight champion, Jake LaMotta, to get in the last word. When he encountered Cus D’Amato, the “Bronx Bull” congratulated him and said, “Cus, it looks like you have another world champion in that boy.”13

Mike Tyson’s Atlantic City debut was a smashing success. Even though the fight was not shown on television, the ESPN cable network was determined to televise Mike’s next fight. The live crowd at Resorts International took the young slugger to their hearts immediately, and the hotel was anxious to get him back soon. Everybody associated with the fight card was talking about the unknown sensation from New York. Mike Tyson was a hit. Bob Arum, taking advantage of Tyson’s sudden impact on the Atlantic City scene, scheduled another bout only three weeks later. This time his opponent was a tall, white boxer named John Alderson, and the bout was televised live by ESPN from the Trump Casino Hotel. This fight marked the actual beginning of “star buildup” for the Catskill phenomenon. Between Jim Jacobs, Bob Arum, and ESPN, they set out to make Mike’s next fight an “event.” The fight would also mark Mike Tyson’s first experience at fending off media representatives while trying to concentrate on his opponent.

An ESPN film crew arrived in Catskill, New York, on July 2 to do a special on Mike and Cus D’Amato, a razzle-dazzle piece of film-making that would be shown on the cable station just prior to the Alderson bout. The commentators and camera crew spent the better part of the morning around the Ewald residence, then journeyed to Redman’s Hall to catch Mike in the midst of his training routine. Somehow training went on in as normal a manner as the situation permitted. Cus tried to entice Tom Sullivan back to serve as Mike’s sparring partner again, but he had a prior commitment. This left Tyson in a not-so-unusual predicament, stuck in the gym without a sparring partner. Mike made the best of it as usual and concentrated on the other aspects of his conditioning—the bag exercises, the calisthenics, and the road work.

The big sports news in Catskill over the weekend was tennis, not boxing. It was Wimbledon time again and merry old England was busy sipping tea and eating strawberries soaked with whipped cream. On the courts, Martina Navratilova and Chris Evert Lloyd battled for the women’s championship for the fifth time, and for the fifth time Martina won. The scores were 4–6, 6–3, 6–2. On the men’s side things were a little different. The top seeds, Ivan Lendl, John McEnroe, and Jimmy Connors, were all gone, and the final came down to a battle between eighth-seeded Kevin Curran and an unseeded 17-year-old West German player named Boris Becker. Becker, in all his youthful exuberance, was all over the court making acrobatic saves and subsequent winning volleys. When the smoke cleared, the young German had scaled the heights. He was the first unseeded player ever to win at Wimbledon. And he was the first German player ever to win there.

Mike Tyson wasn’t a big tennis fan, but he could relate to Boris Becker’s accomplishment. He himself was aiming to do a similar thing in the ring. After watching Becker’s performance, he was more convinced than ever that he too could scale the heights. By fight night, Mike was beginning to feel the pressure. He was fighting on the undercard but he was, in reality, the main attraction. He was getting all the publicity and was being offered all the interviews. It was a lot for an 18-year-old kid to cope with, but he handled it with unusual maturity. John Alderson, all 6'5" of him, hailed from Cabin Creek, West Virginia, and he came into the fight with the same professional record as Mike Tyson, 4–0. Alderson had turned pro after compiling a tremendous 154–12 record in the amateurs, but as he entered the ring, he looked a little soft around the middle, a dangerous condition for a Tyson opponent to be in.

The fight got off the mark slowly. Alderson looked like a guy who just wanted to last six rounds, not win the fight, and he kept back-pedaling just out of Tyson’s reach. Mike pursued him but refrained from throwing wild punches. He was intent on looking for a good opening. A Tyson jab bloodied Alderson’s nose near the end of the round, and a left-right combination coming out of a clinch did more damage. In round two, the opening came. At the 1:42 mark, Tyson finally caught Alderson with a stinging left, opening a small cut over the West Virginian’s eye. Another left dazed the big heavyweight, and a follow-up right hand dropped him for an eight count. Back on his feet again, he was fair game for the pride of Catskill, who moved in for the kill. A one-two, left-right combination did the damage. After absorbing the two vicious blows, Alderson pitched forward and Tyson obligingly stepped aside, allowing him to fall to the canvas. He rolled over into a sitting position and stayed there until the bell sounded, ending the round. Between rounds, referee Frank Cappuccino and the ring physician examined the battered fighter, and Cappuccino gave the young man some sage advice. “John, church is out. The fight is over. Come back and fight another day.” Tyson’s record now stood at 5–0 with five quick KO’s. At the post-fight interview, Mike admitted that the pre-fight hype had bothered him slightly. “I felt a little funny because of the star buildup. It felt a little intimidating.”14

The Tyson star was in its ascendency now, and the management team of Jacobs, et al, was determined to keep it there. Jacobs’ crew of experts sat down to map out the publicity campaign that would make Mike Tyson’s name a household word from coast to coast. Publicist Mike Cohen, a short, 30-year-old organization type with close-cropped black hair, mustache and beard, was assigned to keep Mike’s name in all the major newspapers and on all the large television networks. To augment that plan, video cassettes containing the complete footage of all Mike’s professional fights were mailed to every sportswriter and top TV personality in the country. Electrifying knockouts were viewed in hundreds of press rooms and TV stations from Bangor to Burbank. As Wallace Mathews of Newsday said, “It really brought Mike Tyson to the attention of a lot of people who hadn’t seen him, myself included.” Bill Cayton, the advertising genius of the group, with over 30 years experience in the field, knew how to sell a product. “It’s said the press can either make you or break you, but if you’re Mike Tyson, its value is priceless. The press’ attention is really basic to the success of a fighter in terms of the money that fighter can make. The bigger the press, the more prominent the fighter becomes, the greater purses he commands, the more interest he generates.”15

The following Saturday, July 19, Mike made his sixth pro appearance in the ring, this time in Poughkeepsie, New York. The program in the Mid-Hudson Civic Center featured the Catskill Clubber and Larry Sims, a chubby black boxer from Cleveland. Sims, a 30-year-old club fighter with a 10–10 record, approached Tyson very cautiously and stayed out of harm’s way for the first two rounds. At the beginning of round three, Mike trapped his man in the corner and delivered a series of crushing body shots. As soon as Sims dropped his hands to protect his ribs, Tyson caught him with a clean right hook and put him in Never-Never-Land for a full ten minutes. Cus was duly impressed with Mike’s quick ending. “A fighter, once he hurts his man, takes him apart. He opens up with everything. The ability to finish a man is what makes Mike Tyson exciting to the crowds. But he still needs more experience. He needs to go to the body more.” Cus never let Tyson get complacent. He always found an area where Mike needed more work, and he always commented on it to let Mike know that he wasn’t perfect, that he still had to work hard in order to improve his skills further. Cus always had complete faith in the ability of his protégé, and the Sims fight only served to reinforce that faith.

I’m a sculptor. I can picture the ultimate fighter and I keep chipping away until I have created that fighter. I don’t know how long it will take Mike Tyson to become the champion, but if he maintains his discipline and dedication, he can become champion before he’s 22. Mike believes in himself so much, his actions in the ring become intuitive. And once they’re intuitive, nobody can beat him. He can take anybody out. If he hits Holmes, then Holmes will go down too.16

Mike Tyson’s bank account was beginning to grow substantially now, but he was very frugal with his money. He did afford himself one luxury, however. When he got back to Catskill, he rushed out and bought a used car, a snappy-looking Cadillac El Dorado, white with a blue top. At 18 years old, Mike was already a seasoned professional boxer, but as one of his boxing buddies at the gym recalled, his driving expertise did not match his ring prowess. When he first took the Caddy out for a road demo, the car salesman sat frozen in the front seat as Tyson bounced over the curbstone and careened down the highway, seemingly out of control. Mike thrilled to the ride, but the salesman was traumatized. After several minutes of sheer terror, he insisted on driving the car back to the lot himself. In spite of the man’s lack of confidence in Mike’s driving capabilities, the teenager was noticeably impressed with the performance of the vehicle and purchased it for his very own. It was his first sizable acquisition. The fancy car made a big hit with his buddies around Catskill, but it was obvious from the outset that Mike Tyson was not the world’s greatest driver. In fact, his misadventures on the road scared the hell out of his manager, who was sure that Mike would kill himself someday. Not only that, but Mike himself didn’t enjoy driving that much, so it was just a matter of time before the experiment died under its own weight. Mike had also accumulated four driving violations in a relatively short period of time and was grounded by the New York State Registry of Motor Vehicles. It was one of the happiest moments in Cus’s life when Mike told him that he was selling the car. Cus slept easier after the car was gone.

Being a celebrity, even a small one, meant impositions on one’s time by a variety of people out to sell a cause. One cause that Mike was happy to be associated with, however, was the athletic program at the Greene County Correctional Facility. Don Shanagher brought Kevin Rooney and Kevin Breen, the director of the facility, together one day and before long Rooney had organized an active boxing program at the prison. Whenever he could, he recruited Mike Tyson to accompany him inside the walls to talk to the inmates and demonstrate some of the finer points of the sport to them. Mike was delighted to go, and he was a good influence on the inmates, having been where they were, and having survived the incarceration to begin a new and productive life. When he spoke to them, it was the real thing. “I was a bum, too. I was an inmate. I spent my time in the joint, and look at me.” Don Shanagher used Mike as an example, reminding the inmates, “Mike was destined to sit in an electric chair some place, but he got his breaks here.”17

Two newsworthy events occurred in the baseball world in early August, both on the fourth of the month. Tom Seaver, one of baseball’s finest pitchers, achieved his 300th victory in his 19th major league season, beating the New York Yankees, 4–1. To make the honor even sweeter, Seaver accomplished the feat in front of his favorite fans, the people of New York. On the same day, 3,000 miles away, another 19-year veteran of the Bigs smacked out his 3,000th major league hit. Rod Carew went one-for-five in the Angels’ 6–5 win over the Minnesota Twins.

Seaver and Carew were relaxing in the soft glow of recognition that followed an illustrious career in sports. Mike Tyson’s life, on the other hand, in the infancy of his professional career, was becoming a blur since the initiation of the new publicity campaign. His fights seemed to come one after another in rapid-fire succession. The days and weeks between the fights were filled with business obligations as well as his rigorous training responsibilities. Newspaper reporters by the dozen sought him out, and his manager, Jim Jacobs, was most obliging. Anybody who could get Mike’s name in the newspapers was welcomed in Catskill with open arms.

But when all was said and done, the fight was the thing, and the fight must go on at all costs. After sparring with Carlos DeLeon in Catskill for a couple of days, Mike was matched against another old pro in the gym. James Broad, rated number four by the IBC, brought his 16–4 professional record to Redman’s Hall. Broad, who had been in with the likes of “Terrible Tim” Witherspoon and Marvis Frazier, stopped over for seven days to stretch Tyson’s skills a little further. After Broad departed, the Tyson group broke camp and made the long trek down to Atlantic City, this time to take on Lorenzo Canady at Resorts International. People questioned Canady’s credentials as an opponent, but as Cus explained, “We don’t ask about records anymore. We just thank God we have an opponent. I know the fans would like to see him fight top contenders, but that doesn’t make any sense yet. We can’t make any money doin’ that. First Mike needs to establish a reputation and then we’ll take on the top fighters, maybe in a year. In the meantime, we can get the experience fightin’ them in the gym.”

The Canady fight was short and merciful. Twenty seconds after the bell sounded, a Tyson left put the tall, lean Ohio fighter down on one knee in his corner, wondering how he had ever gotten into such a mess. Fifteen seconds later, the two adversaries met in center ring. They both missed haymaker rights simultaneously, but Tyson followed up with a left that found Canady’s jaw, buckling his knees. The Detroit fighter seemed to hang motionless in space for an eternity and then slumped to his knees and fell over on his side for the full count. It was another electrifying knockout for Mike Tyson, the entire proceedings lasting only 58 seconds. In his first seven professional fights, the kid from Catskill had labored in the ring for only 25 minutes and 27 seconds, slightly more than one round per fight.

The truth was that Mike was getting more competition in the gym than in his official fights. In addition to Carlos DeLeon, James Broad, Tyrone Armstrong, and Tom Sullivan, Mike had traded blows with the likes of Carl “The Truth” Williams, Tyrell Biggs, Jimmy Young and Frank Bruno. Needless to say, it was a picnic when Mike stepped into the ring against his nondescript opponents, if and when he could even find a nondescript opponent. His next scheduled fight, on August 20, was cancelled when five possible candidates pulled out rather than step into the ring with the Catskill Cruncher. Finally, Michael “Jack” Johnson, a cruiserweight who had been inactive for over two years, volunteered to face the Catskill assassin. He should have stayed inactive. As WTEN CH-10 News in Albany reported, Tyson attacked the body immediately, and a left hook to the liver area put Johnson down for the first time. As soon as he arose, Tyson was after him. Rooney was yelling from the corner, “The 8–2, Michael, the 8–2.” Tyson got the message. The 8–2 maneuver, a right hook to the rib cage followed immediately by a right uppercut to the jaw, was executed with pinpoint precision, and Jack Johnson was history, another victim of the New York “Hit Man.” Total elapsed time, 39 seconds. And the loser was on his way to the hospital for observation.

On Friday, September 13, Cus D’Amato travelled to Albany, New York, to address a sales meeting at a local investment company. The subject of the talk was positive thinking, something that many people think was invented by Cus during his years in the Grammercy Gym. The talk eventually got around to his young ward, Mike Tyson, a subject that Cus loved to talk about.

Now I have presently a young fighter, a fella by the name of Tyson. You must have heard of him already in this area. Tyson will be a champion of the world, and the only thing that will stop him is if he allows anything to interfere with his objective and dedication. Now what could interfere? Well, when boys are young and, at that age very healthy, his interest in girls may be so that it becomes a distraction. Now interest in girls is a healthy thing, it isn’t a problem. But it can become a problem. When you’re trying to achieve an objective everything can become a problem when the problem causes your objective to be secondary rather than primary. Everybody knows it, yet when we live it, we somehow don’t observe it. Now what do I do? I put ’em on a track. And as he goes along on the track, he goes off. All I do is put him back on the track. Now I could do it in such a way where I can be right on him, and have my hands on his shoulders so to speak, with complete confidence, until he reaches his objective, but in the end he’ll have confidence in me, not confidence in himself, because he can feel my hand on his shoulder. He’s got to be able to do it himself. And I know how I do it at least. I start him on the track and when he goes off, I just put him back on the track. Let him continue. Follow behind him, but without touching him. Let him continue doing it until he reaches his objective. If a person believes he’s gonna win, he will win. And he will generate the qualities necessary to win, the competitive spirit, the determination, the will to win, just like this young Tyson. He’s beaten fellas that have four, five times, even ten times more experience than he has. He’ll make mistakes a great deal more, but he’ll overcome them because of this quality that he was able to generate. Mike Tyson has meant everything to me. If it weren’t for him, I probably wouldn’t be living today. He’s got my adrenaline flowin’ again.

Cus’s voice was raspy during the talk, causing him to clear his throat frequently. It was the first symptom of the insidious illness that would take his life less than two months later. Cus’s final battle with death was another vivid reminder that boxing was, after all, only a sport and not a microcosm of life. But Cus believed he had done his job well. He believed he had prepared Mike Tyson for every eventuality, including his impending death. Cus had put Mike Tyson on the track to the championship, and he believed that Mike had developed the necessary independence to continue on his own after his adopted father was gone.18

Real life, and its associated tragedies, were being painfully experienced on September 19 by countless thousands of people a continent away in Mexico City, where a devastating earthquake wreaked death and destruction over 20 percent of the mountain metropolis. Earth tremors measuring 7.8 on the Richter scale struck the Mexican capital early Thursday morning, flattening entire neighborhoods and destroying large sections of the business district. Fortunately the quake struck before the workday began, minimizing the number of casualties but, even so, estimates of the dead were put at a staggering 20,000!

Back in Catskill, New York, the Mexican tragedy was just an item in the newspaper, a catastrophe that seemed almost unreal, certainly incomprehensible to a young man whose whole life was concentrated in a 324-square-foot padded enclosure surrounded by ropes. As Tyson’s regimen continued, the heavyweight championship was changing hands. On September 21, Michael Spinks, an inflated light heavyweight, took the title away from an over-the-hill Larry Holmes. It was a dull, 15-round affair. Spinks wouldn’t fight, and Holmes was too tired to fight. When Mike saw the debacle, he told the Daily Mail, “I’ll fight him right now. That fight disgraced the heavyweights. Spinks is only a light heavyweight. It’s unbelievable. He should give me a title shot right now.” Cus was a little more cautious. “Tyson has five more fights scheduled and then we’ll see.” With visions of heavyweight championship belts dancing in his head, Mike Tyson took a new oath of dedication to his profession. “I want respect. That’s what it’s all about, to get the respect of everybody. No more girls. No more night life. I’m gonna show everybody.”

Once again, however, Tyson’s career was slowed by a lack of qualified adversaries. A scheduled bout in the Felt Forum was called off when the opponent took a powder after concluding that the $700 payday wasn’t worth the pain and suffering he would experience in the ring. Subsequently, Tyson’s next fight was moved to Atlantic City where the larger $1,500 purse would entice more opponents out of the woodwork. After several frustrating weeks, an opponent and a date were finalized. Mike’s adversary was to be Donnie Long, who had replaced Tony Anthony, who had replaced Dion Simpson. And the merry-go-round continued. It was impossible to tell Tyson’s many prospective opponents without a scorecard. It was easy to keep track of his sparring partners. There were none. As a result, Tyson was forced to take out his frustrations in the ring by pounding away at Kevin Rooney’s big catcher’s mitts, and by working over his body bag. He also jogged his usual five miles a day. Even at this early stage in his career, Mike spent much of his free time promoting his home town, getting involved in various anti-drug campaigns, and generally trying to be a model citizen. He had already learned to handle the media politely, no matter how aggressive or insensitive they might be. “I can always afford to be a gentleman. I think everybody should. I’m a good guy basically. And I wanna help other kids go straight. Kids shouldn’t be involved with drugs. They should be involved with academics, school, sports.”

On October 9, Donnie Long brought a respectable 15–3 record and ten KO’s into the ring at the Trump Hotel and Casino. Although both fighters tipped the scales at 215 pounds, Long’s 6'2" height made him look bigger than his stockier foe. Tyson, attired in white shoes and trunks, had not yet assumed the intimidating all-black dress that would become his trademark as a top-rated contender, but his approach to the fight was just as black and just as simple—seek and destroy. The fight as usual was short-lived and took longer to write about than it did to experience. Tyson stalked his foe from the outset, and before a minute had passed he took command. As he maneuvered his man back toward the ropes, Mike faked a right hand, then leaped in with a thundering left hook to the jaw that bounced Long off the bottom strand of ropes and onto the seat of his pants. The courageous kid from Youngstown, Ohio, bounced up in a flash, but he was unable to stop the Tyson onslaught. The Catskill assassin came right at him as soon as referee Cappuccino satisfied himself that Long was able to continue. Tyson moved in quickly, his face a study in concentration. In center ring, he unleashed a right-left combo that put Long in full retreat. A roundhouse left staggered the taller fighter, and another bounced him off the ropes. Rights and lefts rained all over Long’s head, two uppercuts snapped his head upright, and a crushing left hook put him down on one knee.