The year 1986 was to be Mike Tyson’s road to the title, the year when he would challenge the top pretenders to the throne and dismantle them, one by one. That was the plan. But before Mike would be turned loose on the top-ranked fighters, his managers had one other goal for him to reach first: Rocky Marciano’s knockout record. Marciano had KO’d his first 16 opponents in the professional ranks, and Tyson’s record now stood at 15. Jim Jacobs wanted to break that record before turning Mike loose to make a run for the gold. Opponent number 16, the man who would allow Mike Tyson to tie Marciano’s record, was Dave Jaco, a tall, frail-looking white boxer fighting out of Bay City, Michigan. Jaco, at 6'5" tall, carried a deceptive 215 pounds on his lanky frame. Although he brought a respectable 19–5 record into the fight, the Michigan fighter was considered no more than another stepping stone for the new heavyweight sensation. The Empire State Plaza in Albany, New York, was jammed to the rafters on the night of January 11. A standing room only crowd of 3,000 screaming Tyson fans were on hand to witness his attempt at the KO record. Ticket prices were scaled from $15 for general admission to $40 for ringside, an unheard-of price for a relatively obscure boxing card, but the Tyson mystique in upstate New York gave the match an almost championship atmosphere.

Mike entered the arena carrying his usual small canvas gym bag long before the crowd arrived, and was followed to the dressing room by three pigtailed blonde admirers. Dave Jaco, another of Tyson’s journeymen opponents, was not concentrating on a victory on this night. His objective was only to go the route with the new heavyweight sensation. Even that would be difficult according to Jaco: “It will take sheer will to keep me up for ten rounds.” The main event was 45 minutes late starting, and the impatient crowd began their usual rhythmic hand clapping and foot stomping. They were understandably anxious to see the dynamic heavyweight in action and to participate in a small segment of ring history. When Jaco finally made an appearance and headed down the aisle to the ring, he was greeted with a generous round of applause from the congregation. Moments later, however, the building shook with tumultuous cheering as the crowd caught sight of the burly Tyson leaving the dressing room. The kid from Catskill forced his way down the crowded steps accompanied only by his trainer, Kevin Rooney, and his cut man, Matt Baranski. Every person in the arena was on his feet, screaming and whistling, some standing on their chairs to get a better view. The noise was deafening. As Tyson climbed through the ropes, his face was solemn. His eyes were fixed in a dark stare as he prepared himself for his next hurdle. He was unclothed as usual, save for his white boxing shoes and white trunks. He wore no socks. He wore no robe. He was once again the gladiator entering the arena to do battle to the death.

Tyson knocked down Dave Jaco three times in round 1 for a TKO win at 2:16 (courtesy Paul V. Post).

Jaco was visibly agitated at the sight of his muscular adversary. He tried to keep Tyson at a distance once the fight started, but he was not strong enough to prevent the aggressive 19-year-old from bulling his way inside. Jaco appeared to be wary of his notorious opponent, and he punched ineffectively off his rear foot while backpedaling away from the advancing Tyson. Jaco stuck a jab in the kid’s face to keep him at bay, but Tyson walked right through it. Jaco missed with a right. Tyson had him in a corner now and dropped the outgunned Michigan heavyweight to his hands and knees with a stinging left hook. As soon as Jaco regained his feet, Tyson backed him into another corner, and another left hook buckled his legs. He crumpled to the canvas in a heap as Tyson watched and waited. Although Jaco’s talent was non-existent compared with Tyson’s, his heart was big, and he once again struggled to his feet. The game Midwesterner tried to stay out of harm’s way but that was impossible. He managed to avoid one Tyson left, but a follow-up clubbing right hand to the top of his head sent him sprawling again, face-first to the canvas. The referee jumped in and stopped the fight immediately, invoking the mandatory three knockdown rule. It was over, mercifully in the first round, and Mike Tyson had equaled the record of the legendary Rocky Marciano by KO’ing his 16th straight opponent. Tyson was low-keyed and all business at the post-fight interview. “It’s just a business. Jaco is a professional. He lost because of the three knockdown rule, but if there was no rule and I didn’t catch him right, he would have kept gettin’ up and I would have had to knock him down 10 or 15 more times.”1

Late in the month, a national tragedy took the nation’s focus off the sports pages. On January 28, the space shuttle Challenger, the 25th flight in a frenzied NASA program designed to establish a permanent space station high above Earth, had lifted off from Launch Pad 39-B at precisely 11:38 a.m. with a seven-person crew including a New Hampshire school teacher. Seventy-two seconds into the flight, the Challenger exploded, sending the cabin section plummeting into the Atlantic Ocean, shattering on impact and killing all seven occupants.

January also saw the changing of the guard in one of the heavyweight groups, although the result was tainted and unpalatable. “Terrible Tim” Witherspoon decisioned WBA champion Tony Tubbs in a drab title fight but, more importantly, traces of marijuana were found in Witherspoon’s urine during a post-fight examination. After a hasty meeting of WBA officials, it was decided that Witherspoon would be allowed to retain the title, but he would also have to give Tubbs a rematch within six months. He was also fined $25,000. The incident was just another example of the sorry state of affairs the heavyweight division was in. The heavyweights needed a champion who could set a good example for the youth of the country and serve as a positive role model for the inner city blacks. Mike Tyson was making his move and was as concerned about his image as he was about winning the title, telling Roy S. Johnson of Penthouse, “I want to work on being a good person. Some athletes have trouble when they retire because after awhile they start to believe what people think they are, and forget who they really are.”2

Less than two weeks after the Jaco fight, “Kid Dynamite” was back in the ring, this time in Atlantic City. Mike’s opponent was Irish Mike Jameson, a 31-year-old pro from Cupertino, California. Tyson’s manager, Jim Jacobs, was not happy when he learned that Jameson was substituting for Phil Brown, who had to withdraw with an injury. Brown was a superbly muscled fighter, but one well suited to Tyson’s brawling style. Jameson, on the other hand, was known as a survivor, a tough Irish kid who had carried several rated fighters into the later rounds. The statistics on the two fighters gave Tyson a decided advantage. The kid from Catskill was younger, stronger, and faster than his more experienced adversary. Physically he was as solid as a rock, built like a finely chiseled Greek statue. Jameson, carrying 236 pounds on his 6'4' frame, had a height, weight, and reach advantage, but the California heavyweight was soft around the middle and had little foot speed, two attributes made to order for a young bull like Tyson.

On fight night, the Trump Hotel and Casino, one of the many high-rise hotels that decorated the Atlantic City Boardwalk, was crowded with boxing buffs anxious to get their first look at the new heavyweight sensation. The match, promoted by the Houston Boxing Association, was scheduled for eight rounds and was televised live by ESPN. Irish Mike Jameson, true to his heritage, entered the ring decked out in kelly green trunks with a white shamrock. Tyson made his appearance dressed in black once again. That color would be his trademark from now on. Tyson’s managers thought black was an intimidating color, and along with Mike’s menacing sneer, the image that he presented would strike fear into the hearts of many opponents. Jacobs and Tyson were convinced that the dark visage of the heavyweight executioner would win many fights before the first bell had rung. And they were right. Jameson paced nervously around the 20-foot ring as he awaited the pre-fight festivities. Tyson was more composed, standing quietly in his corner receiving last-minute instructions from Rooney. Referee Joe Cortez waved the two fighters to center ring to get their final instructions. A mustachioed Mike Jameson brought his 17–9 record with eight KO’s with him. He was soon joined by the man the media was now calling “Iron Mike,” perfect at 16–0. Tyson’s face was expressionless as he listened to Cortez, like a man deep in concentration. He didn’t even acknowledge the cheers of the crowd. He was mentally preparing himself for the task at hand, that of destroying Mike Jameson.

After the ritualistic handshake, the two antagonists returned to their respective corners to await the bell. Ringside commentators Ken Wilson and Murray Sutherland were previewing the fight, particularly as it reflected on the overall future of the heavyweight division. Sutherland added to the Tyson mystique with his glowing commentary. “Mike is a ray of sunshine coming to the heavyweight division—a division sadly lacking exciting opponents. There is a need for someone with Mike’s explosive power to bring back the days of George Foreman, Joe Frazier, and Sonny Liston.” Time would tell if Mike was the man.

The bell sounded and the Catskill strongboy advanced to the center of the ring to meet the journeyman from sunny California. An early right by Jameson caught Tyson on the side of the head, but the youngster responded with a sharp right uppercut of his own. Tyson stalked his man like a sleek jungle cat, weaving and bobbing, moving forward, always forward. Mike unleashed a short flurry on the ropes but Jameson escaped serious difficulty. The constant diet of body punches was already bringing the big guy’s hands down. Tyson scored with a good uppercut and ended the round with a furious two-pronged attack to the head and body. Two hard rights to the head, one on top of the head that brought a grimace to his face, hurt Jameson, and he later said, “It felt like my neck went down to my belly button.”

In round two, Jameson, the 1972 California Golden Gloves champion, landed a solid right to the side of Tyson’s head, but it didn’t seem to bother Mike at all. The Catskill Clubber came back with a fierce body attack, always moving forward. He didn’t take a backward step the entire fight. A sharp uppercut opened a deep gash over Jameson’s left eye, causing blood to flow freely down the side of his face. Jameson’s lumbering style made him a sitting duck for the swift Tyson. He was unable to escape from Mike’s withering attack, and he was frequently trapped on the ropes where the young New Yorker could bang away at will before Jameson could tie him up.

The scenario remained unchanged in round three. Tyson backed Jameson to the ropes at every opportunity and worked his body with dozens of rights and lefts, all of them thrown with bad intentions, a Tyson trademark. The big heavyweight from Cupertino began to hold more often now as he realized his chances of survival were becoming slimmer with each Tyson attack. Mysteriously, the bell sounded to end the round at the 2:01 mark—a two-minute round. Mike Jameson probably appreciated the thoughtfulness of the timekeeper.

In round four, Mike Tyson continued to follow his fight plan. Jameson was warned for butting a couple of times early in the round, but that didn’t slow Tyson down either. The pride of Catskill quickly pinned the Irishman on the ropes, as had been his practice throughout the fight. A crushing left hook followed by two lightning left uppercuts dropped the Californian to the canvas in his own corner at 1:08. The speed with which Mike put together three-, four-, and five-punch combinations was unheard-of in the heavyweight division. He had the speed of a lightweight combined with the power of a heavyweight, a frightening combination for an opponent to ponder. Floyd Patterson had been credited with having the fastest hands in heavyweight history, but Mike Tyson was faster, according to the man who should know, Cus D’Amato. Jameson was on his feet quickly, shaking his head to clear the cobwebs, but Tyson gave him no relief. As soon as the referee waved the two fighters together, the determined Tyson rushed in for the kill. Jameson tried to tie up the rambunctious New Yorker with but moderate success. The Cupertino heavyweight proved his toughness in this round by surviving an all-out onslaught by the frenzied teenager.

Mike Jameson was the first opponent to last more than four rounds with Tyson (photograph by the author).

Tyson was out quickly in round five and immediately maneuvered his man into a neutral corner. A hard combination followed by an overhand right put Jameson down on one knee. Referee Joe Cortez asked Jameson if he wanted to continue as he wiped off the big guy’s gloves. Receiving no positive response after his third query, he stopped the fight. Mike Tyson was declared the winner on a TKO at 46 seconds of round five, his 17th successive knockout. Jameson appeared to be frantic and distraught when Cortez called it off, but boxing insiders claimed that Jameson’s tantrum was all a charade. According to those in the know, Cortez put the question to Jameson three times. “Are you all right? Do you want to continue?” Having received no answer from Jameson, the referee had no choice but to stop the fight, at which point Jameson finally responded, “I’m all right. I’m all right.” As all boxers know, the referee can’t think for them. It is the boxer’s responsibility to let the referee know if he wants to continue or not. Jameson obviously did not want to take any more punishment from “Kid Dynamite.”3

With Rocky Marciano’s knockout record tucked safely in his back pocket, Mike Tyson could now begin to move up in class. From now on, his managers would schedule world class boxers. The final phase of his long, arduous, and frenetic campaign toward the heavyweight championship was about to begin. From that day long ago, in September of 1980, when a scared 14-year-old street kid from Brownsville arrived at the Ewald house on the banks of the Hudson, the major effort of Cus D’Amato, Jim Jacobs, and Bill Cayton was directed toward placing the young boy on the heavyweight throne sometime before March of 1988, a timetable that would make him the youngest heavyweight champion in history. D’Amato’s boxing expertise, Jacobs’ management skills, and Cayton’s promotional talents were carefully orchestrated to produce the best world class fighter in the world, a fighter who was known around the globe, and a fighter whose image could demand multi-million dollar purses whenever he fought.

The countdown had begun, and Jesse “Thunder” Ferguson was first on the list. Ferguson was the ESPN champion. Rated number 16 in the world, he carried a record of 16–1 with 10 KO’s into the ring. His only loss was a tenth-round knockout at the hands of Carl “The Truth” Williams, and he had Williams on the canvas twice before his luck ran out. The fight would be a major hurdle for the youthful Tyson and would determine if he was ready to handle the top contenders.

Outside the ring, Mike Tyson was getting a taste of what it was like to be a celebrity. He completed his first television commercial in January, a 30-second slot for an Albany, New York, electronics store. Tyson was shown throwing punches at the air while an unseen voice said, “Heavyweight Mike Tyson is tough on the competition.” At the end of the pitch from the electronics firm, Tyson pointed to the camera and said, “We knock out competition.” At least it was a start. Also outside the ring, the boxing community was formulating a plan to unify the heavyweight title for the first time in more than six years. Early in 1986 there were three men who all claimed to be the true champion. First there was Michael Spinks, probably the closest thing to a true champions there was. Spinks was recognized as the title holder by the International Boxing Federation. Then there was Pinklon Thomas, the WBC champion, and Tim Witherspoon, the WBA king, in truth nothing more than pretenders to the throne.

Boxing promoters Don King and Butch Lewis, under an umbrella called the “Dynamic Duo,” after months of difficult negotiations with Home Box Office (HBO) cable TV, announced the details of an elimination tournament to crown a unified champion. The scenario had Witherspoon fighting Englishman Frank Bruno in March, Michael Spinks defending his newly won IBF crown against former titleholder Larry Holmes, and Pinklon Thomas putting his WBA belt on the line against Trevor Berbick. The WBA and WBC winners would then unify two-thirds of the title with a box-off in November, while the IBF champ defended his title against the European champion, Steffen Tangstad, on the same card. Finally, early in 1987, the two champions would meet in the final unification bout to crown the one true heavyweight champion.

Many talented heavyweights were excluded from the tournament, including Gerry Cooney, Carl Williams, and Mike Weaver, and their managers were screaming “foul” and talking about collusion and “deals” in all the national “rags.” Mike Tyson was also ignored when the tournament was engineered, but that was as it should have been. Mike was coming on strong, but he still did not have the credentials to qualify as a serious contender. He was close, however, as witnessed by the fact that the HBO Vice President for Sports, Ross Greenberg, made the trip from Manhattan to Troy to study the new heavyweight sensation first-hand. Although Mike’s mentor, Cus D’Amato, was no longer around to choreograph his career, his co-managers, Jim Jacobs and Bill Cayton, were still grooming him very carefully. His opponents were still hand-picked, and his rate of progress was monitored meticulously. His schedule would not be accelerated just to satisfy the whims of the Don Kings and HBO. When his time came, Mike Tyson would be ready. As Jacobs told HBO, “Our chief responsibility over the past year has been to select the right opponents for Mike Tyson. Nothing else has been more important. When people watch Mike Tyson fight, we want them to leave the arena saying, ‘When can we see him again?’ And that’s where Bill and I are scrupulously careful in determining who he fights and the style of the fighter.”

February 16 arrived, surprisingly sunny and pleasant for a winter day in upstate New York, and the city of Troy was buzzing with excitement. The author was on site to record all the sights and sounds of the big day as well as to report on the fight itself. The RPI Field House stood silent and peaceful as dawn broke over the blue collar community, and the people began to prepare themselves for another typical Sunday respite—church services, the Sunday newspaper, and pro basketball on TV. Those sports fans who were lucky enough to get tickets to the fight would head for the Field House about noontime, but the rest of the locals would have to be satisfied with the basketball game since the fight was blacked out for a 50-mile radius around Troy. As midday approached, the quiet serenity of the neighborhood was transformed into a three-ring circus as almost 8,000 rabid Tyson fans descended on the tiny area, media people by the dozens jockeyed for position in and around the Field House, and blue-uniformed lawmen struggled to maintain peace and order in the environs.

The crowd started to trickle into the arena as soon as the doors were opened at 1:00 p.m. one hour before the first fight would start and two-and-a-half hours before the hometown hero would enter the ring. A lonely 16-foot, eight-inch ring stood in the center of the gymnasium floor, visited periodically by various handlers from both the Tyson and Ferguson camps who were methodically checking the structure for defects. They tested the tightness of the ropes, the consistency of the canvas, and even the location of the television platforms to make sure that the scaffolds would not be a serious distraction to their fighter. ABC Sports was on hand to televise the fight, the first in their million dollar package with the Tyson group. The scaffolding had been erected in several locations around the ring to support the permanent TV camera installations that would provide a variety of camera angles of the event. In addition to the fixed units, a number of portable cameras would be present at ringside to portray the action “up close and personal.” Sportscasters Jim Lampley and Alex Wallau were early arrivals to the arena to survey their territory, to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the Field House itself, to confirm the strategic positions of the permanent cameras, and to run through their pre-fight comments and analysis.

The $20 grandstand seats filled rapidly once the doors were opened as local boxing fanatics filtered into the arena jabbering and gesticulating, anxious to see everything that was being offered. They generally armed themselves with hot dogs and cold beer, then settled comfortably into their seats to witness the entire card, from the first four-round prelim to the final match of the day sometime around six o’clock. Beer and “dogs” were consumed voraciously in these seats. The $50 ringside seats filled less rapidly, some of them remaining empty until just before the 3:30 scheduled time for the Tyson-Ferguson main event. Many ringsiders were celebrity attendees, less interested in the bouts themselves than in being seen at a television event. Others were there on business—members of the New York Boxing Commission, promoters, managers, employees of HBO, and local and state politicians. They too were less enthusiastic than the grandstanders.

Mike Tyson, adorned in his favorite leather jacket and carrying a small gym bag, slipped into the arena unnoticed at about 2:30 and made his way to the dressing room. His usual entourage of three pigtailed blondes trailed obediently behind like puppy dogs. As one preliminary fight after another went the distance, the crowd became larger and more raucous. When the hands of the clock passed the 3:30 mark, the anxious crowd began to hoot and clap their hands. Within minutes, Jesse “Thunder” Ferguson finally came into view and was welcomed into the ring with but a smattering of applause from the pro–Tyson crowd. Ferguson climbed through the ropes with a confident smile on his face. He looked well warmed up and ready to go, and his pre-fight comments to ABC were brought to mind once again. “I think I can beat Mike Tyson. I’m gonna stand there and fight him. I won’t run. I think my experience and my punching power will win the fight for me.” Perhaps he was right, but there were 7,600 people in attendance who were of the opinion that, if Ferguson stood toe to toe with the Catskill assassin, he would leave the ring on his shield.

The buzzing that filled the arena during the minutes immediately preceding the fight suddenly erupted into a deafening roar as the pride of New York emerged from the dressing room. He was not yet in full sight of the crowd but already the rafters reverberated with thunder as 7,600 frenzied fans screamed, whistled, stamped their feet, and began the rhythmic chant, “Ty-son, Ty-son, Ty-son.” If the roof had separated from the building as a result of the tumultuous welcome for their hometown hero, not one person in the building would have been surprised. Ross Greenberg, Vice President of Sports for HBO, at ringside, looked around incredulously at the wild scene. He said he had never in his life witnessed such an enthusiastic welcome for an athlete. Although the noise continued unabated for a full three minutes, Mike Tyson was oblivious to it. He was stone-faced and impassive as he strolled down the aisle to the ring, the omnipresent black shoes and black trunks his only attire, his moist bronze body glistening threateningly in the glare of the Field House lights. Once inside the ring, Mike stood quietly in his corner while his trainer laced on the eight-ounce thumbless gloves that are mandatory in the state of New York. Rooney then spread liberal amounts of Vaseline around his fighter’s eyebrows and cheekbones, as a normal precaution against cuts. The lubricant reduces the friction on a fighter’s face, allowing an opponent’s glove to slide off his face harmlessly instead of grabbing the skin and opening a nasty wound in the process. It doesn’t prevent all cuts, but it does minimize those caused by friction.

When Tyson was formally introduced to the crowd, another wild demonstration was ignited. A group of enthusiastic Tyson fans at ringside stood and waved placards to the crowd glorifying their hero’s professional achievements. One man held a card aloft reading “Fight 1–KO,” another “Fight 2–KO,” another “Fight 3–KO,” and so on all the way up to Fight 17. The group vigorously urged Mike to continue the string and make Ferguson knockout victim number 18. Mike did not acknowledge the roar of the crowd, although later he remarked, “It was great, but I like to hear my name announced, you know.”4 As referee Luis Rivera gave the fighters their final instructions, Alex Wallau at ringside summarized the importance of the fight for television viewers. “Tyson is stepping up from fighting journeymen fighters to fighting a quality opponent. The heavyweight division right now is in chaos with three champions. If Mike Tyson is for real, he could be the star that this division and this sport need very badly.”

Tyson’s emotions appeared to be under control as fight time approached. He calmly bounced up and down in his corner, pounding his gloves together in anticipation. At the bell, his placid countenance suddenly changed. A cloud came over his face and his expression turned dark and sinister. He was once again the gladiator, and it was killed or be killed in the arena, with no quarter asked or given. Tyson was a man on a mission, and his mission on this day was to club Jesse Ferguson into submission as quickly as possible. Tyson met the ESPN champion in center ring and immediately maneuvered him into a neutral corner where he exploded six vicious body punches to the ribs and liver area. Five more body shots were delivered with bad intentions. Ferguson tried to fight back but his single punch was drowned out by a Tyson avalanche. Two thundering rights dug deep into Ferguson’s side. The round was only a minute old and already Ferguson had taken enough body shots to last an entire fight. Two dynamite left uppercuts straightened the lanky Ferguson up and forced him to respond with four or five punches of his own in sheer desperation. Tyson brought three more crushing lefts up from the floor to crash against Jesse’s liver area. Whomp! Whomp! Whomp! Lesser opponents would already have called it a night against Tyson’s onslaught, but Jesse Ferguson was no average fighter. He was a cut above Tyson’s previous opponents. Tyson’s attack became more varied now, as he shifted from body punches to occasional lefts and rights to the head that stunned Ferguson. The round was less than half over when two tremendous left hooks found the side of Ferguson’s face. Tyson had already thrown 40 or 50 punches in this fight, and every one of them was designed to maim or kill. Ferguson landed his first good punch of the fight, a short right uppercut that snapped Tyson’s head back. The action continued at a rapid-fire rate for the rest of the round with Ferguson fighting back but Tyson still landing the more telling blows.

Jesse Ferguson lost to Tyson by disqualification in round 6 when he refused to break from a clinch when ordered by the referee (courtesy Paul V. Post).

Rounds two and three were fought on the ropes with Tyson maneuvering for position and Ferguson trying to keep the Catskill strongboy at bay. A crushing right uppercut thrown by Ferguson found Tyson’s chin, but Mike’s only response was a counterattack of his own. In round four, Ferguson was able to keep Tyson at arm’s length. As a result, most of the action took place in the center of the ring. Tyson became more tentative in this round, perhaps beginning to pace himself for a possible ten-round match, perhaps just looking for the one big opening. There was a minor fracas at the end of the round when Tyson landed a hard right hand to Ferguson’s body after the bell. The infraction inflamed Jesse and caused his handlers to leap into the ring, but order was quickly restored before things got out of hand.

As round five started, Ferguson came out boxing and jabbing more than at any time in the fight. Tyson didn’t throw a punch for almost a minute, choosing instead to stalk his man, biding his time and waiting for a clean shot. Several times Tyson had the ESPN champion backed into a neutral corner without throwing a punch. Once again, he pushed Ferguson’s body against the ropes. This time a flurry of body punches brought Ferguson’s guard down, which is exactly what the kid from Catskill was looking for. A Tyson left uppercut connected, but with not much on it. That was followed by a hard right to the rib cage, then a lightning right uppercut that broke Ferguson’s nose, snapping his head back and driving him back against the ropes. The big man’s knees buckled, his body crumpled, and he pitched forward to the canvas. He rolled over on his back and lay motionless, his hands held high as if shielding his eyes from the lights. His smashed nose spurted blood. Tyson was an eerie sight as he turned away from his fallen foe and walked slowly to a neutral corner. His hands were straight down by his sides, and a strange, almost evil leer covered his face. Mike explained the reason for his reaction to Paul Post of the Daily Mail after the fight. “I was laughing because when you know somethin’s gonna happen, it’s amusing.”

Jesse Ferguson survived that punch and escaped another 30-second pummeling by Mike Tyson to end the round. But the former Marine from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, was still not fully recovered when round six started. He tried to give himself time to clear the cobwebs by holding whenever Tyson moved in close, a tactic that brought several warnings from the referee. Rivera had difficulty separating the two fighters on several occasions, and when Ferguson continued to grab and hold in defiance of his directives, Rivera had no choice but to stop the fight, disqualifying Ferguson and awarding Tyson a technical knockout at 1:19 of the round.5

In interviews after the fight, Tyson insisted that Ferguson’s tactics did not discourage him. “They can’t beat me by hittin’ and holdin’,” he said. “It’s a ten round fight and sooner or later I’m gonna get him.” Asked why he changed his tactics after the first three rounds, Tyson volunteered, “In the fourth round I was watchin’ his shoulders and watchin’ the punches he was throwin’ so I could counter them. At the end of the fourth round, I saw an opening and I knew I was gonna hit him with an uppercut and finish him.” Alex Wallau noted that Tyson didn’t appear to be winded at all after his six-round battle, and he also noted that Mike had taken some good shots from Ferguson without any noticeable ill effects, two areas that the critics were leery about. Tyson just shrugged off their doubts. “I can’t change any opinions. Perhaps some people still have doubts about me, but as I continue to win and to meet all the contenders in the near future, then I will quiet all doubts.” Trainer Kevin Rooney rated Mike’s performance a “B.” “He’ll never get an A+, but I expect to give him a lot of straight A’s. We mark on perfection.”6 All in all, it was a stunning start to Mike Tyson’s charge to the top of the heavyweight ranks. One national boxing magazine called it “electrifying.” And electrifying it was. His performance was dominating, his demeanor terrifying. Perhaps it was time for Rocky Balboa and Apollo Creed to step aside. The real “Master of Disaster” had arrived on the scene. And his name was Mike Tyson.

Ross Greenberg was another who considered Tyson’s achievement to be monumental. He hurried back to his HBO offices greatly impressed with the new heavyweight challenger. He immediately informed his staff that it was almost certain that Mike Tyson would have to be included in the heavyweight unification tournament before it reached its final resolution. Negotiations were ordered to begin at once with Big Fights, Inc. After weeks of discussions between the two parties, Jim Jacobs made the momentous announcement. Big Fights, Inc. had just concluded a package deal with HBO that would put one million dollars in Mike Tyson’s pockets for appearing exclusively on HBO in four fights during the upcoming year. Coupled with the ABC offer, Mike was assured of earning almost two million dollars for eight matches in 1986. The date was March 19. The Tyson camp still had not committed their valuable property to the heavyweight elimination tournament, but they had made assurances to the HBO-Don King group that they would continue to negotiate through the summer and would make a final decision by Labor Day.

During this period, Mike began driving automobiles again, his license having been returned by the Registry of Motor Vehicles. Mike had spent the previous year being escorted around in a bright new chauffeured limousine, placed at his disposal by his manager, Jim Jacobs. Now he could chauffeur himself around again. He didn’t rush out and buy a new car this time, however. Remembering his previous experience, he was more cautious the second time around. One of the Catskill city administrators owned a yellow Cadillac convertible, and he put the car at Mike’s disposal from time to time. Mike got a lot of use out of that yellow Caddy during the summer of 1986. He was spotted driving all over the north country, from Albany, New York, to Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Many days he drove the Caddy up to Catskill High School to visit Mr. Stickles, Mr. Turek, and some of his favorite teachers. Occasionally he took a bunch of the high school kids out for a joy ride. Mike was a hero to most of the teenagers in Catskill, and he delighted in the adulation and the responsibility. He was still a big kid himself, and he loved to impress the youngsters. It was hard to believe, but he was only a year or two older than some of them.7

Being a celebrity was not all fun and games for the teenage idol, however. There were always people searching for the dark side of a public figure’s life. An article in the Boston Globe accused Mike of using lewd and obscene language to female patrons in an Albany department store. A security guard at the mall also stated that Mike and several of his friends were asked to leave the local cinema for cursing at customers. True or not, it created reams of adverse publicity in the sports pages of the nation’s newspapers. Articles like this one made Mike painfully aware of the tremendous impact his actions could have on his life. He was no longer just a private citizen. He was now a public figure, and as such would spend the rest of his life in the journalistic fishbowl. The eye of every reporter and the ear of every freelance journalist would be on him continually from now on. His smallest transgression would be noticed, and it would be magnified and twisted beyond recognition by the purveyors of sensationalism, and elaborately displayed to the world on the cover of one of the weekly scandal sheets.

Mike had only three weeks to prepare for his next opponent, journeyman Steve Zouski, a scheduled “breather” strategically slotted between two name opponents, Ferguson and James “Quick” Tillis. But Mike Tyson was still experiencing growing pains at this time, still maturing emotionally. His mind continued to play games with him, telling him that he could coast through certain matches without giving a full effort and without preparing for the fight properly. Such was the case with the Zouski match. Mike did not train with his usual zest, occasionally skipping a day completely and, on other days, engaging in half-hearted sparring sessions with Charles “Tombstone” Smith. In Mike’s juvenile mind, Zouski was a stiff who didn’t have to be taken seriously. He confided to a friend, “He’s nothin’. I can beat him easily.” As a result of his confused thinking, fight day found Mike Tyson mentally unprepared for battle. To make matters worse, he fell off his pigeon coop in the morning, damaging the cartilage in his ear and laying the foundation for a full-scale infection. To Mike’s dismay, the Zouski bout was a lackluster affair from start to finish. Mike exhibited few of the skills that had vaulted him into the top ten in the WBC’s latest ratings. He seemed to be fighting in a daze, throwing far too few punches and getting hit too often in return.

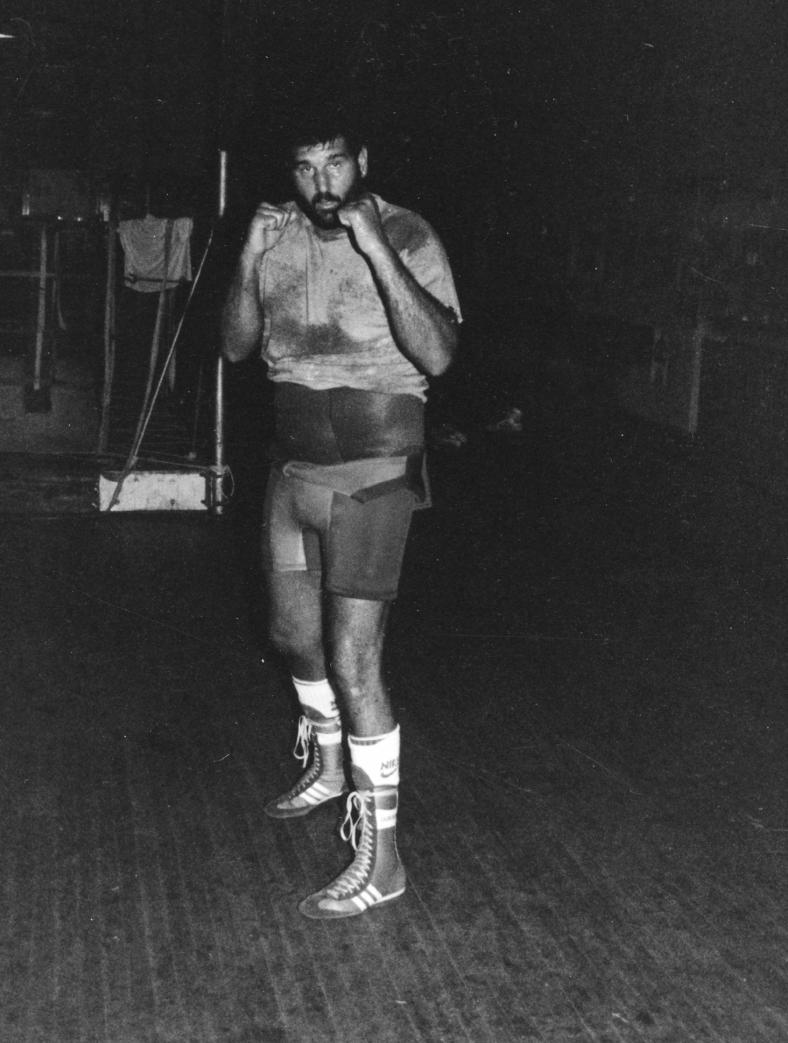

Tyson thought he looked like a tank in this photograph (courtesy Paul V. Post).

The 6,000 Tyson fans that crowded into Long Island’s Nassau Coliseum began to wonder what was wrong with the Catskill assassin. True, Steve Zouski had gone ten rounds with current IBF cruiserweight champ Lee Roy Murphy, and his 25–10 record included 14 knockouts, but the Brockton, Massachusetts, native was not around to see the sixth round against either Marvis Frazier or Tony Tubbs. His fleshy midsection was ample proof that his conditioning program left something to be desired. Tyson contented himself with working Zouski’s soft middle during round one, leaving a series of bright pink welts wherever his thumbless gloves made contact. Mike landed several telling uppercuts in round two but took a number of hard shots in return, uncharacteristic of a mentally prepared Tyson. As round three got underway, Kevin Rooney grew impatient with his charge, at one point yelling, “If you don’t start punchin’, this bum will go ten rounds with you.” Perhaps Tyson heard his trainer’s admonition, perhaps not. In any case, he suddenly unloaded the big artillery. A left hand followed by two whistling rights staggered his courageous foe. Another right hurt Zouski, and one final powerful left hook that smashed against the right side of Zouski’s head sent the challenger to the canvas face-first for the full count. Referee Arthur Mercante counted the dazed Zouski out at precisely 2:49.

According to Rooney, Tyson rated a C+ for his effort, but based on the questions and answers at the post-fight press conference, most journalists, and even Tyson himself, gave the Catskill boxer a much lower score. Mike admitted that it was his worst performance ever, saying that he was suffering from a cold and that he had “a lot of personal problems.” Within three days of the Zouski fight, Mike Tyson was back in the gym sparring with Marc Machain and “Tombstone” Smith, readying himself for the Tillis fight, only 16 days hence. Mike was forced to don the unaccustomed headgear in order to protect his injured ear, which was becoming more irritated with each passing day.8

The following week, Mike was the recipient of a prestigious honor, official recognition by the New York State Legislature. Mike and his trainer, Kevin Rooney, traveled to the state capital at Albany on Tuesday, March 19, to receive the honor. Assemblyman C. D. “Larry” Lane introduced Tyson to the legislature, and Assembly Speaker Stanley Fink presented the young boxer with the framed resolution. It read, in part, “It is the sense of this legislative body to publicly recognize and commend … [Mike Tyson] … an individual of singular and truly compelling distinction … for his outstanding professional career.” With all the adverse publicity that Mike Tyson had received in recent weeks, it was questionable whether or not he could live up to the accolades he had just received. But fate entered the picture at this point and gave the New York teenager a much-needed break in his grueling schedule. The ear infection that had been developing since the Zouski fight suddenly hit Mike with full force, sending him reeling to the hospital for ten days of rest and treatment. It forced a postponement of the Tillis fight until May 3, and gave the beleaguered 19-year-old time to reexamine his recent escapades and get his head back together. He thoughtfully reviewed his behavior and his attitude over the past few months, his recent frivolous nighttime activities with people who were supposed to be his friends, but who in fact turned him away from his objective and caused considerable consternation in the Ewald household and in the offices of Big Fights, Inc. Headlines in the nation’s sports pages referred to “nights away from home,” “a girl a night,” and “lewd behavior in public places.”

Tyson took out Steve Zouski in round 3 (courtesy Paul V. Post).

Tyson was honored by the New York State Assembly March 19, 1986, with a framed resolution commending his “singular and truly compelling distinction” (courtesy Paul V. Post).

As Mike rested in his hospital bed, he utilized his convalescence to full advantage. He rededicated himself to the goal that he and Cus had first set back in 1980, to win the heavyweight championship of the world. He would not be distracted by girls or by the exciting city nightlife. And he would choose his friends more carefully in the future. Former stablemate John Chetti was confident that Mike would regain his common sense and renew his dedication to the task ahead. “Now that he’s famous, everyone wants to be his friend. But Mike’s smart. He knows who his friends are.” While Mike Tyson recuperated, a British citizen was creating something of a furor in far-off London Town. Heavyweight challenger Frank Bruno destroyed former champion Gerrie Coetzee at 1:50 of round one to guarantee himself a title fight with the new WBA king, Tim Witherspoon, during the summer, as part of the HBO box-off. The hard-punching Bruno improved his record to an impressive 28–1 with 27 knockouts, his only loss being a tenth-round KO at the hands of the unpredictable James “Bonecrusher” Smith.

When Mike Tyson took leave of Mt. Sinai Hospital and returned to Catskill, New York, to resume his training program for the Tillis fight, he was a new man. He had matured considerably in the ten days spent in isolation, making full use of his time away from home to reflect on his short but hectic career as a sports celebrity, and on the distractions that had caused him to ignore his trade and to betray his promise to his deceased manager. Cus D’Amato had warned him about the dangers he would have to face when he became a celebrity. They discussed these very possibilities many times over the years as the former Brooklyn street urchin was growing and developing, both physically and emotionally. Cus told Mike that the hardest thing he would have to face was how to handle himself once he became a celebrity. “It is difficult getting to the top,” Cus had said, “but it is more difficult handling the success once you have achieved your goal.” Now Mike understood what the venerable old trainer was trying to tell him. Now he was back on track, and he promised not to make the same mistake twice.

He returned to the gym on April 7 to begin his training program for the “Quick” Tillis fight, and he was all business. He knew he had only four weeks to get ready for the toughest fight of his career, and he didn’t want to waste a minute of it. Mike Tyson attacked his training program and his sparring partners with a vengeance. The kid from Catskill knocked out the lower front teeth of one sparring partner, Charlie “Tombstone” Smith. And he punished former world class heavyweight Jimmy Young, dropping him with a vicious left hook. Young, who had driven George Foreman into retirement and who had lost a controversial 15-round title fight to Muhammad Ali, was impressed with the youngster’s talent. “You’re not allowed to bat your eye. He knocked me down the first day and the second day, and I don’t get knocked down in the gym.”9 In the opposition camp, “Quick” Tillis was also busy mastering the fundamentals. The 28-year-old “fighting cowboy” from Tulsa, Oklahoma, was on a four-fight losing streak, including decision losses to Gerrie Coetzee and Tyrell Biggs, but those bouts were now ancient history. Admittedly, Tillis was out of condition for those fights, but against Tyson he had something to prove. He had the best reason of all to get in top condition, incentive. Mike Tyson was the hottest piece of boxing property to come along since Jack Dempsey, and Mr. Tillis wanted to show the world that he was the better man. Come May 3, Mike Tyson had better be in the best shape of his short career because James “Quick” Tillis was coming to the fight loaded for bear.

In spite of his recent setbacks, Tillis still had an impressive set of credentials. His overall record showed 31 victories against only eight losses, and 24 of his opponents were put to sleep before the final bell sounded. Tillis arrived in Glens Falls, New York, brimming with confidence for his big match, and he was sure he knew how to beat Tyson. “You gotta keep movin’ against Tyson. You gotta go side to side and in and out, keep movin’ so he can’t catch you. Hold him, rope him, all that stuff. My great grandfather was a cowboy, so it’s in my blood. From the root to the fruit, I’m in this game to make big money. I wouldn’t want to work hard and train hard just to be a punchin’ bag for somebody. I want to get back on top—in the limelight.”10

More than 7,500 screaming fans were on hand to welcome “Kid Dynamite” to the Glens Falls Civic Center. He was glad to be back after a seven-week layoff caused by the ear infection that pushed the Tillis fight back from its original March 29 date. “(The hospital) was the best thing that ever happened to me. It was like a vacation. Not being in the gym took off a lot of pressure and gave me time to think and relax. I thought about what I wanted to do; did I want to be a playboy and hang out or fight. I found out I wanted to fight.” The parade to the ring encompassed the usual Tyson entourage—local security people, followed by Rooney, Tyson, assistant manager Steve Lott, and cut man Matt Baranski. Needless to say, pandemonium reigned while the somber Tyson pushed his way through the crush of people. A hint of a smile crossed his face as he slipped between the ring ropes. There was a joke around town about the new Mike Tyson doll. You just wind it up and it comes out punching. Sure enough, when the bell sounded, the Tyson “doll” came out swinging. Mike was his usual aggressive self, bobbing and weaving, moving forward, mixing hard rights and lefts to the body with an occasional shot to the head. It was obvious that he intended to try and take Tillis out early. But “Quick” Tillis came prepared. He was in great physical condition, and he was ready for Tyson’s tactics. He slipped most of Mike’s rushes rather easily, although he did take a few hard shots in the process. Mostly he kept the young brawler at bay, pushing him away when he got close and landing several good counterpunches of his own in the process. One uppercut in particular caught Tyson clean but left no ill effects on the youngster’s sturdy chin. Tyson landed a solid right to the head early in round two, but Tillis grabbed and clinched immediately. Tyson continued to pursue his man throughout the round but couldn’t catch the dancing cowboy.

The Catskill teenager shifted tactics in the next round, becoming more of a boxer and less of a brawler. The early part of the round was dominated by frequent clinches as the man from Tulsa wouldn’t let the young slugger cut loose on him. But that scenario finally ended when Mike trapped his man on the ropes and unloaded. A hard right to the body was followed by a left hook to the head. Now the punches came fast and furious as Tyson unleashed a vicious attack to press his advantage. Left-right-left. A hard right to the side of the head knocked Tillis sideways along the ropes. Half a dozen more punches found their mark before Tillis could tie up his energetic adversary. In spite of all Mike’s punishment, the “fighting cowboy” was back on the balls of his feet, dancing away from danger and bringing feelings of doubt to the young boxer. Tillis caught Tyson with several good left hooks in round four, but Tyson walked right through them like nothing had happened. That was a plus for Tyson because Tillis was a known hard puncher. He had Marvis Frazier on the canvas, he had Greg Page down, and he dropped Carl Williams twice. But the tough New Yorker didn’t even acknowledge that he had been hit. At one point in the round, Tyson went into a low crouch that left the top of his head even with Tillis’ knee. After a subsequent clinch, the Oklahoma cowboy lunged at his man with a hard left to the head that missed. Tyson slipped the punch as Tillis went by, spun around and caught the off-balance fighter with a left hook, dropping him to the canvas, more surprised than hurt.

As the middle of the fight approached, Mike Tyson became very tentative. He wasn’t his usual busy self in the clinches, he put together no rapid-fire combinations, and he seemed to have lost some of his drive. The crowd became curious. Was it out of respect for Tillis? Was he now in awe of his crafty opponent? Was he tired? Was he pacing himself? What was his problem? On one scorecard, Tyson had won rounds 2, 3, 4, and 6, with rounds 1 and 5 being scored even. Tillis had not won a single round at that point, but suddenly he began to come on, and Mike Tyson began to fade. Tyson managed to come out on top in a sluggish round 7, but rounds 8 and 9 were dominated by the Oklahoma cowboy, although they were so dull that Kevin Rooney implored his young charge to “keep punchin’. Don’t stop in the clinches.” The final round was no different. Mike Tyson kept the lid on until the final 30 seconds, when he opened up and finished with a flurry. Tyson eked out a close decision by a 6–4, 6–4, 8–2 count, but he left many questions unanswered in the process. He certainly did not impress anyone with his lackadaisical performance in this fight.

The days following the Tillis fight were times of soul-searching for the Tyson camp. The fight itself had been less than an artistic success, and unkind guttural murmurings could already be heard throughout the boxing world. First of all, the fans were unhappy. Tyson followers across the country had expected Mike to claim his 20th consecutive victim via the knockout route, and his inability to do so left them disgruntled and angry. Boxing fans, in general, are a bloodthirsty lot, and Tyson fans in particular crave their share of the sticky red stuff. Nothing less than witnessing an opponent being bludgeoned into unconsciousness will satisfy the appetite for gore and mayhem. Boxing experts around the nation were also dissatisfied with Tyson’s lethargic performance, and they continued to question his determination and his stamina over the ten-round distance. Certainly his inactivity over the last four rounds of the fight fanned the flames of that still raging controversy. Mike had been content just to lay on his opponent and rest whenever Tillis tied him up in rounds seven through ten, his dynamite right hand hanging useless at his side. At a time when he should have been taking Tillis apart piece by piece with devastating body shots, Tyson did nothing. Stamina. Did he have enough stamina to compete in the heavyweight ranks over a grueling ten- to 15-round route, or was he strictly a six-round fighter? The jury was still out on that question, according to sportswriters.

The brain trust of the Tyson group set about to answer that question to their own satisfaction. One thing that all members of the Tyson camp agreed upon was that a fighter’s first ten-round bout is more than a punishing physical effort. It is a frightening excursion into the unknown. It is a mind-boggling psychological obstacle that must be overcome, a mysterious, tenuous wall that has to be breached before a boxer can pass from the club fighter stage into the arena of the professional pugilist. Self-doubts play on one’s mind, making the task at hand larger than life-size, until it appears to be an insurmountable barrier of mammoth proportions. A boxer’s character is tested at times like these. He needs to keep his goal in the proper perspective and proceed toward it one step at a time. He must challenge the training regimen day by day, always keeping sight of his objective and determining what will be required of him in order to achieve it. And on fight night, the same procedure must be followed. The fighter must maintain absolute concentration, focus all his energies on the fight one round at a time, and not let the big picture overwhelm him. If he does this, and if his conditioning has been satisfactory, he will succeed and the ten-round demon will be crushed forever.

Tyson had breached the wall, although in retrospect it seemed at times as if he had tip-toed over it. Still, the ten-round hurdle was a thing of the past, and a sigh of relief could be heard emanating from the secluded confines of Catskill, New York. Jim Jacobs, for one, was more than satisfied with Mike’s performance. He passed the test and, in the process, he had laid a good beating on Tillis for the first six rounds. Had he not gone into a shell over the last four rounds in order to conserve his energy, it is very likely that he would have made Tillis knockout victim number 20. Kevin Rooney had rated Mike’s achievement a C+ in his school of hard knocks. The young trainer grades his students just like a college professor, marking their level of skill and execution in such areas as defense, aggressiveness, ringmanship, effort, and consistency. According to Rooney, none of his students will ever achieve a perfect mark of A+ on their report card, as noted previously. Tyson’s C+ was considered satisfactory for this stage of his development, although it was far from outstanding.

Rooney predicted, however, that Mike would be advancing to the B level in his upcoming fights, and should be producing straight A’s consistently by the end of the year—just in time to challenge for the title. Certainly Rooney could breathe a little easier after the Tillis fight. He had done his job and he had done it well. Tyson was in superb physical condition and was able to compete at a high level of consistency over the ten-round distance. From the looks of it, he could have extended his effort to 12 or 15 rounds without a problem. Mike finished the fight with a lot of gas left in his tank, and the fact that he became ultra-conservative as the fight progressed was not Rooney’s fault. The mind plays strange tricks on a person. Mike Tyson had struggled with the mind game for weeks prior to the Tillis fight. He was troubled and tormented by the demons of self-doubt, but in the end he emerged victorious. From now on, the ten-round bugaboo would be a piece of cake. With that hurdle behind him, it was time for Mike to look ahead to his next hurdle, another ten-round test against the WBC’s seventh-rated contender, the Bronx bad boy, Mitch “Blood” Green. Mike had only 17 days to prepare for the fight, which would be held in the high temple of boxing, New York’s Madison Square Garden. This fight would be not only a boxing match, it would be an “event.” Jim Jacobs, Bill Cayton, and HBO would see to that. This was Mike’s first fight for HBO under his million dollar contract, and both his managers and the people at HBO wanted to make the most of it.

The fight was being promoted by HBO in conjunction with Don King Productions. Don King, the flamboyant one, was a typical American success story. Born in Cleveland in 1933, King, his sister and four brothers were raised by their mother after their father was killed in an industrial accident. As a teenager, King operated on the fringes of the criminal element in town, eventually working his way into the position of the “Numbers Czar.” King’s world came crashing down around his ears, however, one night in 1965, when he accidentally killed a man during an argument. His conviction on a manslaughter charge resulted in a four-year stint in the Marion Correctional Institution. Once released, King decided that he could make as much money legally as he could running numbers, and with none of the risks. In a short time, he became a boxing manager, his first notable fighter being “The Acorn,” Muhammad Ali’s favorite name for the tough, hard-hitting, and bald Ernie Shavers, whose contract Don King purchased from former major league pitcher Dean Chance for $8,000. Two years later, King branched out into promoting fights, eventually snatching the brass ring with the Foreman-Ali match in Zaire on October 30, 1974. In addition to his multi-faceted business acumen, Don King is also a showman of the first magnitude. He wears his hair in a long, wild, Afro style, looking like a man with his finger in a light socket. The gaudy, diamond-studded rings that dominate his hands complement his sequined tuxedos, frilled shirts, and gold necklaces. One national magazine probably came closest to characterizing Don King when it referred to him as “Flamboyant, ostentatious, cunning, ruthless, part businessman, part con-man, part riverboat gambler, part revivalist preacher. And brilliant.” And the man knows how to make money, too.

This group—Jacobs-Cayton, HBO, and Don King—were embarking on the final phase of the campaign to sell Mike Tyson. The Green fight would mark the beginning of the gigantic promotion that was designed to culminate in a Tyson title fight on HBO late in the year. The first step in the plan was to move Mike Tyson’s training camp to New York City, where a major media blitz could be initiated. During the second week of May, the Tyson camp was uprooted and moved from the back woods of Catskill to the Grammercy Gym in Manhattan. Rooney insisted on Grammercy this time because, as he told Bob Smith at the Daily Mail, “everybody goes to Gleason’s, but I would always train in the Grammercy Gym because it was Cus’s gym. It’s cleaner and bigger than most of the other gyms in the area.” In the boxing world, the Grammercy Gym was known as “the gym that Cus built.” Mike Tyson’s first task in the big city was not sparring. It was not running. And it was not doing calisthenics. It was playing another game of “meet the press,” a chore that Tyson always despised. He got tired of answering the same old questions over and over. “I’m looking forward to fighting in Madison Square Garden. All the great fights in history have been fought in the Garden. It’s a great opportunity. I love what I do. I’d fight three times a week if I could.” And on. And on. And on.

There was a slight possibility that the fight would not even be held in Madison Square Garden, but would be pre-empted by a professional hockey game. The New York Rangers were playing in the Stanley Cup Playoffs and, should they make it to the finals, the sixth game would be played on May 20 in the Garden. If this remote possibility came to pass, the fight would be moved next door to the Felt Forum, the smaller, 4,000-seat arena in the Garden complex. Shortly after Tyson arrived in New York, Don King scheduled a press conference in the Waldorf Astoria to introduce both fighters to the press and, hopefully, lay the groundwork for a crowd-appealing and money-making hate-hate relationship between the two fighters. Mitch “Blood” Green did his part to bring about that hate-hate relationship. Mitchell Green was a native of the Harlem section of the Bronx, a tough street kid who had to fight for survival from the time he was old enough to walk. When he was still a youngster, his fights often ended with the other guy cut and bleeding, causing one of his buddies to remark, “They oughta call you Blood.” And so Blood it was. Mitchell Green had earned a nickname. But that was all Mitchell Green had. That and his life in the streets. He became the leader of one of the local street gangs, The Warriors, and his life became one constant conflict with the dedicated minions of the law. During his teenage years, Mitchell “Blood” Green spent a great deal of time in and out of courtrooms and jails, much to the dismay of his poor mother. Charlene cried herself to sleep many nights, worrying about her son. She was afraid to answer the phone at night for fear it would be someone telling her that Mitchell had been killed. According to Charlene, boxing proved to be a salvation for her son. He could fight legally, and he could vent his anger and his frustrations on his opponents in the ring instead of in the streets.

And Mitchell Green made good copy. He certainly perked up the press conference for the Tyson fight. As he paraded back and forth around the head table, decked out in an outlandish outfit complete with a long gold earring and a Panama hat, Blood Green boasted about how he would destroy the Tyson legend. “I’m not no bum! Tyson, as for you, I’m gonna break your neck. You can’t whup me. Look at me good like I tole you before. This is ‘Blood’ Mitchell Green. I’m not one of those duffle bags who lay on the ropes. If you show up at Madison Square Garden, you’re gone.” Poor Green should have listened to those young kids on the streets of the Bronx who warned him, “I don’t think you can mess with Tyson, buddy.” Mike Tyson is a quiet man. He doesn’t say much, and he doesn’t make disparaging remarks about his opponents. He also doesn’t like people to make disparaging remarks about him. As he eyed Green’s histrionics, his expression remained placid, but his steely eyes were already planning revenge. Mike’s revenge always took place in the ring. His only public remarks were, “If he makes a mistake, he’s gonna find out for the first time how it feels to get knocked out. You can do a lot of things to Mike Tyson, but intimidating him is a different matter.”11

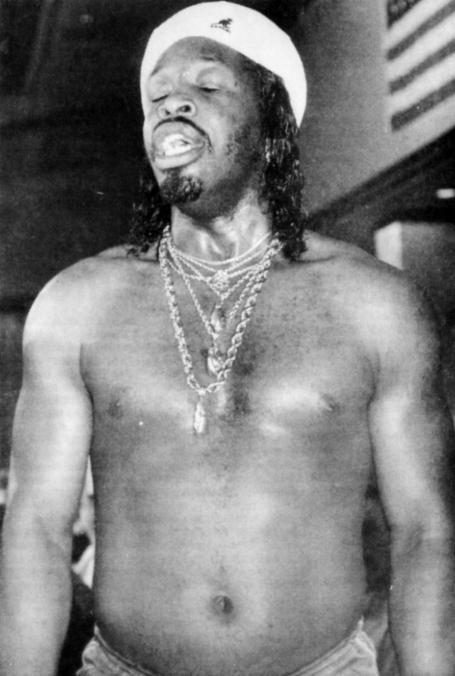

Mitchell “Blood” Green went the distance with Tyson on May 20, 1986, losing by unanimous decision after ten rounds. Green also fared poorly in a highly publicized street fight with Tyson two years later (courtesy Paul Antonelli).

The week proceeded quietly in training camp, with Mike doing his road work in Central Park and his ring work at Grammercy’s. He got in a lot of sparring with heavyweights Wes Smith and Melvin Epps under the watchful eye of trainer Kevin Rooney. Rooney also worked Mike hard on the bags, the jump rope, and the exercise equipment. Still the media blitz continued unabated, making it difficult for Tyson and Rooney to concentrate on the task at hand. One day Mike appeared with Bill Mazer on Sports Extra, Channel 5, New York. During the interview, Mike emphasized the fact that he was going to be champion of the world someday, and he impressed his host with his knowledge of boxing trivia, although he was openly flustered at being asked to parade his wisdom before the American public. When Mazer asked Tyson who Mickey Walker was, Mike replied, “Oh God. Don’t do that to me. You embarrass me.” He also exhibited the humorous side of Mike Tyson to the TV audience.

Mazer: You’re so young. Don’t you worry about burnout?

Tyson: No. The old fighters fought hundreds of fights. One guy had three fights in one day. If you like what you’re doin’, you can do it frequently. You guys come to work every day and you like your job.

Mazer: Yeah, but nobody’s hitting me.

Tyson: Nobody’s hitting me either.

The next night, on the David Letterman Show, Mike commented on the sacrifices that a boxer has to make in order to be successful.

Q: It must be tough for a fighter to have girlfriends with all the training that’s required. Do you have any?

A: I don’t have a girlfriend. I’d like to but I’m a fighter and I have to train all the time.

The Friday weigh-in was a noisy affair with Green storming around bare-chested, complaining about his share of the purse, and threatening to pull out of the match. Green was guaranteed $30,000 for the fight, while Tyson was being paid a cool $200,000. While Green strutted his stuff and boasted about his Adonis-like physique, Tyson just shrugged and noted, “If a body was the only factor, then Arnold Schwarzenegger would be world champion.” At another press conference following the weigh-in, Tyson let the public in on the other side of a celebrity’s life.

People wouldn’t want to be in my shoes. They think so because they say, “Wow! I can get money. I can be rich.” But if they had to go through some of the things I have to go through, they would cry. Sometimes it’s so depressing. Everybody always wants something. They want to find some way to get your money. It’s always people. Just as hard as you work, people are working as hard to separate you from your money.12

Fight night. The Garden was theirs, and 6,529 boxing fans pushed their way through the turnstiles to witness another Tyson demolition derby. Don King and HBO billed the fight as an interborough war with Mitchell “Blood” Green representing the Bronx and Mike Tyson upholding the honor of Brooklyn. Most of the crowd was hoping to see Mike Tyson score a quick and awesome knockout, but Mike himself had other plans. Mike Tyson was angered over Green’s insulting remarks during the week preceding the fight and was determined to make Green pay for his braggadocio. His plan was to punish Green for the full ten rounds, giving him a sound beating, but never taking advantage of an opportunity to knock him out. Mike wanted to make Green quit if he could.

Larry Merchant was at ringside extolling the virtues of Mike Tyson as Mitchell “Blood” Green came jogging down the aisle decked out in a flowing white robe with white fringe on the shoulders and arms. He was loud and noisy and he flicked jabs at the air. The voice of Merchant could be heard in the background. “He’s a spirited, tough kid in the ring, not a classic style but he’ll fight you. He wants to get in there and go dukes with Mike Tyson. The question is can he do it?” The answer wouldn’t be long in coming. Mike Tyson paced his dressing room like a caged tiger thirsting for blood, Mitch Green’s blood. He had listened quietly to Green’s tirades all week, but now the moment of truth had arrived. It was time to put up or shut up. As he left his dressing room, it was a different Mike Tyson that made his way down the aisle. Gone was the look of nonchalance and relaxed gracefulness that had defined the Tyson countenance in previous fights. Now he was all business, dressed in black and unrobed as usual, his face twisted into a grotesque sneer that could only mean trouble for Mitch Green. On this night, Mike Tyson hated the Harlem tough guy with a passion that could not be extinguished. Tonight Mike Tyson would make Mr. Green pay for all those disparaging remarks of the previous week. He vowed to punish Mitch Green for ten long rounds. He would beat him thoroughly and painfully to show Green who was the tougher of the two. And if Green wanted to end the fight prematurely, he would have to quit.

The ringside commentator’s voice was drowned out by the roar of the crowd as the future champion came into view.

Mike Tyson is an awesome prospect, in the process of becoming a fighter, a challenger, a champion. It does seem already, prematurely, he’s being treated like some sort of human trash compacter, expected to just go out there and grind everyone into powder, and if he does anything less, it’s failure. So let’s just remember that even the greatest fighters left some opponents standing and the critics clucking—that he is just 19—and that he’s been a professional for only 14 months.

Announcer Charlie Hull introduced Mitch Green to the crowd amidst polite applause. The 6'5", 225-pound Bronx bomber looked in tip-top condition, his shoulder-length black hair hanging in tiny ringlets, his mustache and goatee neatly trimmed, and his statuesque body glistening in the glare of the ring lights. His ring record was almost as impressive as Tyson’s. Winner of 16 fights with one draw, Green had lost only once, on a close decision to WBC champion Trevor Berbick. This fight was to be his stepping stone to a rematch with Berbick for the title. Tyson glared at his man threateningly during the briefing by referee Luis Rivera and then returned to his corner to receive last-minute instructions and a kiss on the lips from his trainer.

Mitch Green’s dream of glory lasted less than 30 seconds in actual combat. Mike Tyson came out fast and he came out swinging. After the first 20 or 30 Tyson hooks, a look of doubt came over Green’s face. Tyson was a man on a mission, and Green was the target. The big man’s eyes showed concern almost from the start, and he was forced to backpedal and fight a defensive fight before the onslaught of the teenage tiger. To his credit, he fought back when cornered, and he caught his assailant with some telling punches. Still, Tyson took the shots without notice and moved inexorably forward. In round two, the stone-faced Tyson hit Green with a straight jab that sent his mouthpiece flying into the crowd. Green responded by holding Tyson behind the head with his left hand and banging four solid shots to Mike’s head with his right. There were some good exchanges in the early going with both fighters winging and landing some good punches. In round three, a Tyson hook knocked Green’s mouthpiece out again, this time with a bridge and two teeth in it. By now, Mitchell “Blood” Green was becoming very discouraged. The red stuff that covered his trunks was coming from his own mouth instead of his opponent’s. In between rounds, he sat dejectedly on his stool and shook his head in disbelief. Mike Tyson was too much for him. In the other corner, Mike Tyson was enjoying himself. He had the fight well in hand, and he was executing his moves with complete confidence. He continued mixing his punches well, throwing a stiff jab, followed by vicious hooks to the body and a variety of punishing uppercuts and head shots. And every punch was thrown with bad intentions.

In round five, Tyson taunted Green for a minute or so. After talking to his opponent, Tyson laughed at Green and dared the big man to hit him. Mike moved forward, bobbing and weaving, not throwing any punches, slipping every punch that Green threw at him, thoroughly enjoying his defensive abilities. Between rounds eight and nine, Tyson’s exuberance surfaced once again. In the middle of a Rooney lecture, Mike glanced up at his intense trainer, smiled, then kissed him on the cheek. All was well in the Tyson camp. In the end, it was a Tyson runaway. He won the fight handily with Green winning one round at most. Mike was still not winded after 30 minutes of constant activity where he threw almost 500 punches.

At the post-fight interview, Mike confirmed his fight plan. “I don’t want to sound brutish or anything. I didn’t want to knock him out. I wanted to put a lot of pressure on him and make him decide himself whether to give up or not. I hit him with some rugged punches but not devastating punches. I knew he was a professional and if he went down from those punches, he would have given up. And I must take my hat off to him. He’s a very tough individual.” Mike summed up the fight best a little later when he said, “I’m just a 19-year-old kid havin’ a lot of fun.”13

With the Green fight history, the selling of Mike Tyson took off in high gear. Bill Cayton’s strategy for the rest of the year was to keep Mike close to New York City, the media capital of the world, with an occasional side trip to her west coast counterpart, Los Angeles. Mike was scheduled to fight in the New York City area another eight to ten times before challenging for the title in November or December. In between fights, Cayton and Jacobs would see to it that Mike attended as many noteworthy events as possible, making sure to be photographed with famous people in the process. He would also be seen in the company of the world’s most beautiful models and starlets. The New York newspapers were soon full of Mike Tyson photos. His gold, gap-toothed grin was everywhere. One day he was at Gracie Mansion trading jokes with Mayor Edward Koch, and the next day he was at Yankee Stadium autographing a baseball for superstar Dave Winfield. He even found time to make the newsprint in the clutches of Penthouse Pet Cody Carmack. No wonder he was smiling.

Kevin Rooney and Jim Jacobs had to be very careful they did not overdo the promo bit to the exclusion of Mike’s conditioning program. After all, Mike was first and foremost a boxer who was still in pursuit of the title. Getting him in condition for his next fight, only 24 days away, was paramount. His opponent, Reggie Gross, was already in training, and he was intent on derailing the Catskill Express. Gross, out of Baltimore, Maryland, was no pushover. His record showed 18 wins and four losses against some stiff competition, mostly in the cruiserweight division. In his two most recent fights, Gross had scored an impressive eighth-round knockout over highly rated Bert Cooper, then lost a tough ten-round decision to Mike’s old nemesis, Henry Tillman. Come June 13 in Madison Square Garden, Reggie Gross would be standing in front of Mr. Tyson, determined to make him his 19th victim. The sparring sessions in the Cus D’Amato gym were fast and furious during the early part of June as Mike Tyson tangled with some tough competition. In addition to his regular sparring partner, Dion Burgess, Mike was forced to contend with tough Anthony Davis. As everyone knew, Tyson’s sparing sessions were no different from regular bouts. They were wars, with no quarter asked or given. And Mike Tyson fought them without the protective headgear, which he was not allowed to wear unless there was a medical problem that necessitated their use. “We want guys who aren’t afraid to throw bombs,” said Rooney. Anthony Davis was like that, and Rooney appreciated it. But Anthony Davis was no match for a fired-up Mike Tyson, and he had to call a halt to one sparring session after Mike had bloodied his nose. “Whoa. He’s like a rock. I got to stop.”14

Sharing the spotlight with Mike Tyson in Catskill was Edwin “Chapo” Rosario, who was headlining the June 13 Garden card in a WBC title fight against champion Hector “Macho” Camacho. Tyson usually worked out in the gym from 12:30 p.m. until 2:30 p.m. followed by Rosario from three to five. Chapo, at 16–1 with 16 KO’s, was extremely confident of taking the title away from the Macho man, whose record stood at 29–0 with 16 KO’s. While Tyson was focusing his energies on Reggie Gross, his manager, Bill Cayton, was busy announcing his next three fights. On June 28, according to Cayton, Mike was scheduled to meet William Hosea in the RPI Field House in Troy, New York. Less than two weeks later, he would step into the ring at the Stevensville Country Club in the Catskill Mountains to take on Lorenzo Boyd, and on July 26, Mike would be paired with Marvis Frazier in the Glens Falls Civic Center.

When fight night arrived, 10,000 fans filed into Madison Square Garden on what was billed as “Resurrection Night” by the metropolitan media, who were intent on rebuilding the Garden’s reputation as a major boxing arena. The Tyson fight, in fact, was only a secondary fight that evening, yielding the limelight to the WBC lightweight title fight between Camacho and Rosario. When Reggie Gross stepped into the ring, it looked like it would be a long night for the kid from Catskill. Gross, who stood six feet tall, had filled out as a heavyweight and carried 218 pounds on his sturdy frame, one pound more than Tyson. Mentally, Gross was ready for the challenge. He was determined to carry the fight to the youngster. And he was confident that he would destroy the Tyson myth during the course of the evening. The fight turned out to be short and sweet, at least as far as Mike Tyson was concerned. Mike came out quickly as usual, determined to take Gross out in the first round. Gross was just as determined to stand his ground and mix with the young New Yorker. Midway through the round, Gross went on the offensive, throwing a flurry of punches at the teenage sensation. Tyson ducked under a hard right thrown by the determined Gross and took a short left uppercut that caught him flush on the chin. Another short left missed its mark, and a hard right failed to connect as Tyson calmly moved out of harm’s way. Still another right and left found nothing but air as the elusive Tyson bobbed and weaved like a magician. A solid right uppercut finally found its mark and stood Tyson straight up, but the New Yorker’s bull-like neck absorbed most of the force of the devastating blow, leaving Mike alert and ready to counterattack, which he did. After another Gross right sailed over his head, Tyson leaped out of his crouch with a roundhouse left that found Gross’ right cheekbone, dumping the Baltimore fighter on his back. Gross crawled to the ropes on his hands and knees, and pulled himself upright at the count of seven, but his glassy-eyed stare was evidence that the fight was almost over. Tyson followed up his advantage with determination, and two more left hooks put his courageous opponent down again. Gross was beaten but his heart wouldn’t admit it, and once again he pulled his battered body upright. Referee Johnny LoBianco grabbed the wobbly fighter and waived an end to the fight at 2:36 of round one. The fight had been short but not easy.

After the fight, Tyson was ecstatic over his quick victory. “I was lookin’ forward to fightin’ Gross because of his good performances against Cooper and Tillman. I wanted to prove somethin’ tonight. I was determined to knock him out in the first round.”15 When his manager, Jim Jacobs arrived, Tyson was all smiles. “I can’t believe how I avoided all those punches he was throwin’. It was weird.” Jacobs smiled. “That’s because you’re elusive, Mike. You’re very elusive.” One of the reporters questioned Mike about the right uppercut that Gross laid on him. “I saw the punch comin’ and I braced myself for it. It looked devastatin’ but it wasn’t. I wanted him to stand there and trade punches.”16

Tyson’s stablemate, Edwin Rosario, was not as fortunate as Mike, losing an unpopular 12-round decision to Hector Camacho. Twice the rugged Rosario had Camacho on the verge of a knockout but couldn’t finish the job. As soon as Camacho regained his senses, he got on his bicycle and ran away from his tormentor for the rest of the fight, salvaging his title only through the good graces of the judges, not through any effort of his own.