During the nineteenth century, consumption supplanted the great epidemics (such as plague or smallpox) in the public’s imagination. The growing presence of the disease was apparent in England, beginning in the mid-seventeenth century, and its widespread nature was quickly recognized. In the 1674 edition of Morbus Anglicus: or the Anatomy of Consumptions, Gideon Harvey expounded upon those most affected. “It’s a great chance we find, to arrive at one’s grave in the English Climate, without a smack of a Consumption, Death’s direct door to most hard Students, Divines, Physicians, Philosophers, deep Lovers, Zelots in Religion, &c.1 Harvey’s title was a nod to the prevalence of the disease in England, translating as it does into “Disease of the English,2 and this emerging “social scourge” was accompanied by new imagery.

In general, infectious diseases adhere to an epidemic pattern. Initially, they increase very quickly; then, having attained a certain level, slowly fade in intensity and incidence. Despite the fact that the development and course of tuberculosis is less “flashy” than other contagious illnesses, it still follows a typical epidemic cycle of infection, though the progress is often extraordinarily slow, taking decades rather than weeks or months. In Europe, the epidemic curve for tuberculosis began in the latter part of the seventeenth century and peaked in the middle part of the nineteenth. By the close of the nineteenth century, it was still claiming one-seventh of the world’s population and even in 1940 tuberculosis was responsible for a greater loss of life than any other single contagious illness.3 In Great Britain, for the two hundred years preceding 1840, tuberculosis was a major endemic disease afflicting nearly as many individuals as all other diseases combined.4 Whatever the actual numbers, there was certainly an eighteenth-century perception of a rise in mortality for consumption. It was widely acknowledged that the illness was pervasive and deadly. For instance, William Black, who wrote several works concerned with medical statistics, stated in 1788: “from one fifth to one sixth of all the mortality in London, is from consumption; which is nearly double to that even of small pox,” and that “phthisis, phthisis, phthisis, towering with gigantic bulk” dominated the London funeral catalogues.5

Its impact was heightened by the seemingly indiscriminate way in which it claimed its victims, afflicting the denizens of mansions as well as tenements. The disease was rampant in urban centers, but not limited to the city, and showed no respect for gender, status, age, or occupation. In 1818, John Mansford argued consumption was on the rise:

It is as a growing disease that consumption assumes its most important feature. It has with justice been termed the giant malady of the country; and with fearful, and giant-like strides does it gain upon us … It appears probable … that the number of deaths from consumption in Great Britain have increased one-third within the last century; and that they have now reached the enormous amount of fifty-five thousand annually.6

In spite of the conviction that there was an increase in tuberculosis deaths, determining the specific incidences of consumption remains difficult due to the lack of accurate mortality data, a circumstance complicated by the uncertainty of contemporary diagnosis. Consumption’s slow, creeping nature meant that it often remained unnoticed until the latter stages, and its nomenclature further complicates the assessment of mortality. The terms phthisis and pulmonary consumption were used, almost indiscriminately, to indicate a number of unrelated maladies.7 The designation of consumption was particularly problematic, as it was often applied to any illness accompanied by weight loss.

Figure 1.1 Gideon Harvey by A. Hertochs, n.d. Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

In spite of these difficulties, it is clear that the nineteenth century can reliably be termed the “age of consumption,” whether one cites the disease’s actual or imagined impact. It can also be styled the age of medical statistics.8 Until the nineteenth century, there were no regular or accurate records of quantitative mortality kept in England. That is not to say that there had not been attempts, both by institutions such as hospitals as well as by some cities, to keep records of births and deaths. In 1836 a parliamentary mandate formalized these efforts and led to the creation of a nationwide system of registration of births, deaths, and marriages. The following year, the statistician and physician, William Farr, gave up his medical practice and became temporarily employed by the General Registrar Office to assist in arranging and classifying this information and in 1839 his position became permanent.9 With Farr’s publication of The First Annual Report of the Registrar General of Births, Deaths, and Marriages, officials in England began to systematically tracking mortality rates for a variety of diseases, including tuberculosis.

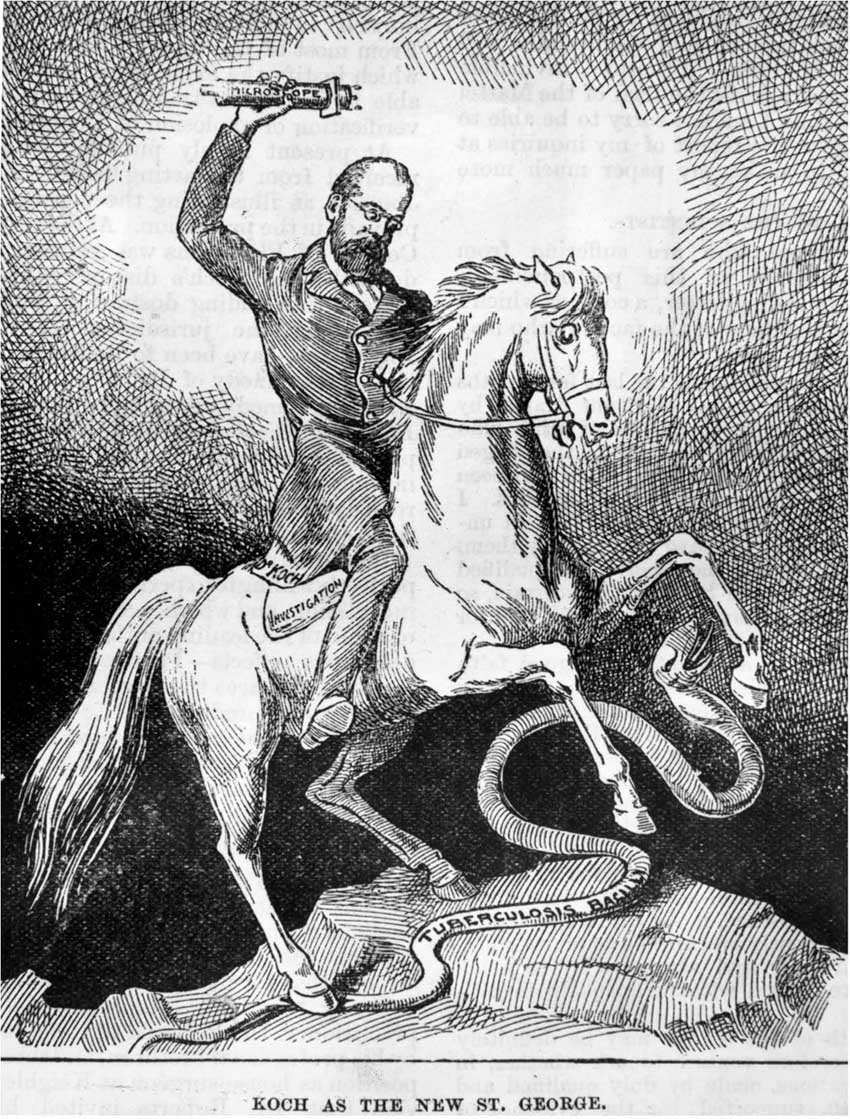

These new statistics bore witness to the nationwide destruction of human life caused by consumption—a situation that did not escape the notice of those chronicling the disease. One such investigator, Henry Gilbert, wrote: “According to the Report of the Registrar-General, pulmonary consumption destroyed more human lives during the six months referred to [July 1 to December 31, 1837], than did cholera, influenza, small-pox, measles, ague, typhus-fever, hydrophobia, apoplexy, hernia, colic, diseases of the liver, stone, rheumatism, ulcers, fistula, and mortification!10 Gilbert quickly put these statistics to use, arguing “There is no disease so universal, and none so mortal, as consumption of the lungs. According to the best data, it has been calculated, by medical men, that it causes one-fourth part of all the deaths occurring from disease in Great Britain and Ireland.11 By 1850 the Annual Reports were publicly highlighting the substantial tuberculosis death rates found in large cities.12 Sizable mortality helped raise public awareness and focused the medical community’s attention on the disease throughout the last half of the nineteenth century. In 1882, Robert Koch wrote of consumption’s impact, “If the number of victims which a disease claims is the measure of its significance, then all diseases, particularly the most dreaded infectious diseases, such as bubonic plague, Asiatic cholera, etc., must rank far behind tuberculosis. Statistics teach that one-seventh of all human beings die of tuberculosis, and that, if one considers only the productive middle-age groups, tuberculosis carries away one-third and often more of these.13

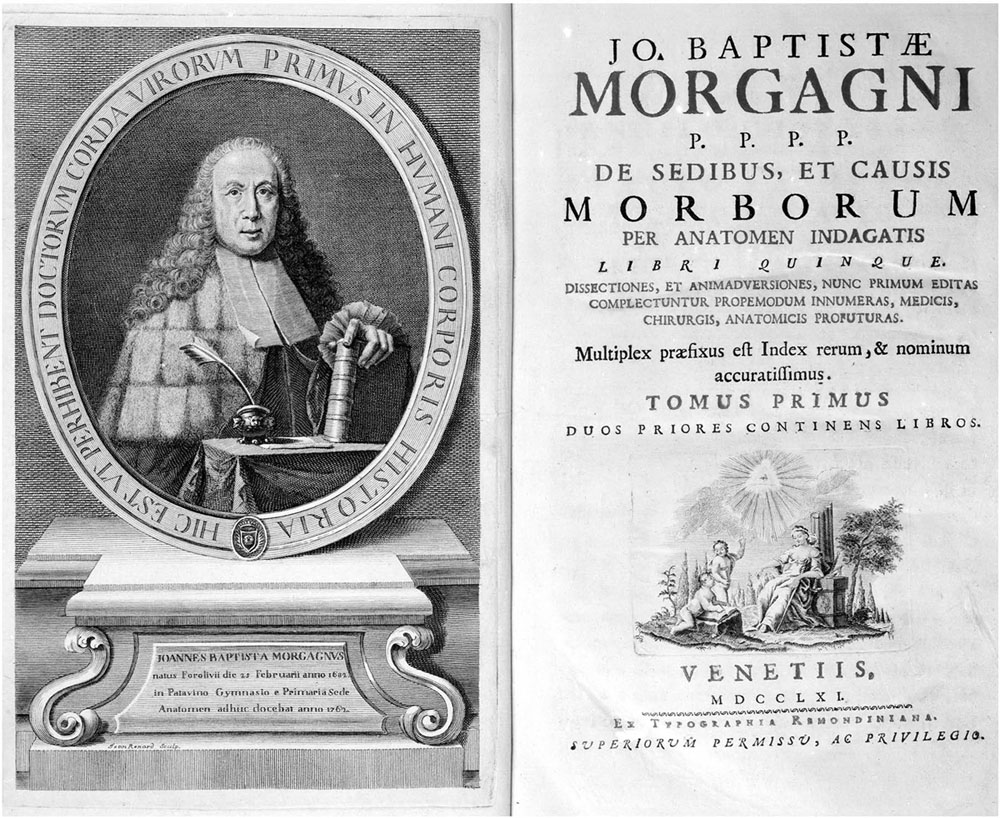

Beyond a growing awareness of the magnitude of the disease, early nineteenth-century attitudes toward tuberculosis reflected the dominance of the anatomico-pathological approach to illness. The eighteenth century witnessed the development of a localized concept of disease, one explored and understood in terms of morbid anatomy. During the 1760s the Italian anatomist, G. B. Morgagni linked sickness to anatomical findings in his work De sedibus et causis morborum, helping to establish the idea that medical investigators should correlate symptoms and lesions through autopsy. He was instrumental in altering the theoretical ideology of illness by elevating pathology and the role played by precise, localized lesions. In this new anatomical perspective, the lens of medical investigation was focused on the parts rather than the whole.14 Increasingly, the symptoms manifested by the living victims of illness were correlated after death with the structural alterations seen post-mortem.15 The ground-breaking French pathological anatomist Xavier Bichat helped define this outlook and charged physicians to dissect and discover.16 Underpinning the new approach was the idea that an illness had specific pathological manifestations and investigation of these particulars would provide answers to the cause of diseases. This alteration in the intellectual approach led to a new way of categorizing the process of disease; however, for consumption, the growth in the depth and quality of anatomical information raised more questions than it answered.

In tuberculosis, the anatomico-pathological approach was limited to diagnostics and the identification of the pathological indicators, but failed to elucidate the causes of these morbid presentations. Slowly medical investigators developed new methodologies and tools to scrutinize the disease process not just in the dead, but also in the living body. To this end, the discovery of percussion and development of the stethoscope helped advance the knowledge of tuberculosis and aid in its diagnosis.17 When Theophile Hyacinthe Laennec created the stethoscope in 1816, he produced an item that would become the primary instrument of the new anatomical approach to medicine. (See Plate 5.) By opening the living body to “dissection” through sound, the stethoscope provided a new vehicle for investigating a diseased individual; pathology could now be performed on the living as well as the dead.18 The stethoscope and accompanying methodology significantly altered the approach to respiratory ailments, and Laennec applied his new weapon to pulmonary consumption. A Treatise on the Diseases of the Chest and on Mediate Auscultation (published in French in 1819 and translated into English by 1821) clearly described the clinical route taken by tuberculosis.19 In the work, Laennec not only established guidelines for diagnosing consumption, but also argued that the tubercle was the signifier of one single malady, whether it was located in the lungs or elsewhere in the body, like the liver or the gut. Laennec proposed a unitary theory of consumption, which became the accepted viewpoint until the discovery of the tubercle bacillus in 1882.20 In 1843, John Hastings paid homage to Laennec’s contributions, stating:

Figure 1.2 Robert Koch as the new Saint George after isolating the tuberculosis bacillus. Editorial #: 3362301 Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Figure 1.3 Giovanni Battista Morgagni. Title page and frontispiece Giovanni Battista Morgagni, De sedibus, et causis morborum (Venice: Remondiniani, 1761). Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

Although various and varied in their character were the works on Pulmonary Consumption before Laennec’s time, his vast discoveries, by means of auscultation, have spread over it a new light, and created another era in its history … But extraordinary as it may appear, our means of cure seem to have diminished, in proportion as our knowledge of determining the character of Consumption has increased; for at no period of its history has it been so fatal as since the discovery of the stethoscope.21

Credence was granted to Laennec’s theories by his contemporary Gaspard Laurent Bayle whose work Recherches sur la phthisie pulmonaire (1810) also argued that tuberculosis was a precise and specific condition rather than some pervasive generalized wasting disorder that occurred as a result of some earlier malady. Additionally, he asserted that tubercles developed first before any outward symptoms appeared. Bayle insisted that the most visible and recognizable symptoms of tuberculosis indicated the degree of the disease’s advance, and that an absence of visible or characteristic symptoms in no way indicated an absence of the disease.22 Bayle’s Recherches provided an analysis of the most frequent pathological manifestations and systematically tracked the organic changes produced during the course of the disease process, performing over nine hundred autopsies and combining the results with his own observations. This comparison of pathological and clinical findings led him to conclude that a small tubercle was the origin of the other lesions in consumption. He declared that the further complications observed in phthisis patients, including those seen in the intestine, larynx, and lymph nodes, were the product of consumption and not a separate illness.23

Sir Robert Carswell’s text on Pathological Anatomy (1838) synthesized and evaluated the numerous descriptions of the tubercle by medical investigators like Laennec, Bayle, and Gabriel Andral and assessed the seeming variability of its nature.24 Carswell was prominent among the British medical men who flocked to France to learn the new anatomico-pathological concepts. There he observed dissections and became familiar with new medical techniques (such as mediate auscultation) while spending time with Pierre Charles Alexandre Louis and Laennec.25 Carswell is perhaps best known for his stunning illustrations of dissections of the anatomical samples he surveyed in France; additionally he remains important for his work in helping to translate pathological anatomy into a distinct medical discipline in England.26 Robert Carswell also demonstrated the continued difficulty of accurately determining the cause and course of tuberculosis. He performed dissections and prepared colored drawings of his observations, which demonstrated localized concepts of disease; however, his accompanying case notes presented a more holistic approach.27 Pathological Anatomy raised several questions that continued to plague the medical community about tubercles. (See Plate 6.) What was the origin of these lesions? What were they, and were they related to the disease process of phthisis? One popular theory presented tubercles as small damaged glands whose enlarged state was the result of the injury done by disease. Others saw tubercles as new entities seeded by the disease and growing in a tumor-like fashion. Speculation continued on everything from the size and consistency of tubercles to their origin and location. Investigations into the nature of the tubercle also raised questions over the exact relationship between the tubercles found in the lungs and those in other parts of the body. In 1849, Robert Hull argued “Pulmonary consumption is a systematic malady. A lung may suffer alone, or in common with the viscera of the abdomen.28 The question remained: was there a relationship between these extra-pulmonary tubercles present in scrofula, for example, and those in pulmonary phthisis?29 Despite the influence of Bayle and the work of those like Hull, the majority of physicians seem to have viewed these varying pathological symptoms as the result of other, unrelated illnesses.

In an attempt to establish some order over this perplexing wealth of information, medical investigators deliberately categorized different conditions by the type of ulcer, tubercle, or cavity that was present.30 Cases in which tubercles manifested outside of the lungs had a different designation than consumption and, until the late nineteenth century, they were believed to be distinct but related diseases with their own etiologies and treatments. When Carswell argued that the study of consumption should fall under the aegis of pathological anatomy, he acknowledged the limits of available knowledge and addressed the role played by factors such as the elements and the economy, as well as the acquired or hereditary nature of the illness. But what was this nature? A theory that covered the holes left by the anatomico-pathological approach was necessary, and heredity received the nod for a number of illnesses, including tuberculosis.

There was a widespread acknowledgment of the prevalence and destructive nature of pulmonary consumption, but determining its cause, diagnosis, and treatment proved elusive. In 1808, James Sanders lamented this pervasive ignorance, writing:

One could scarcely perceive from their writings, that authors had ever attempted to relate the symptoms in the order of their occurrence and consistently with the changes which succeed in the constitution; and this probably is the chief cause, that they do not agree with regard to its nature, though of bodies deprived of life by consumption an infinite number has been examined with great patience and anatomical discrimination.31

Nearly half a century later the confusion remained, and in 1855 Henry M’Cormac wrote, “For generations phthisis has been the opprobrium of medicine. No disease perhaps has been more patiently investigated, yet none has more frequently baffled inquiry, or has been more extensively abandoned to empiricism and despair.32