Pathological anatomy advanced the understanding of how tuberculosis manifested in the body; however, it did little to account for variable susceptibility or the source of the tubercles. The theories put forward were diverse and on the European continent, particularly in the south, consumption was generally regarded as a contagious disease, one spread through the air or through contact with either infected persons or materials.1 Elsewhere—in England for instance—tuberculosis was viewed as the result of a breakdown in an individual’s constitution, a flaw that was frequently inherited, passed from parents to offspring like physical characteristics such as facial features and hair color.2 Contagion theory failed to provide an explanation for all of the observed incidences of consumption and many theorists simultaneously supported the concept of tuberculosis as both a contagious and an heredity illness. Physicians, like Gideon Harvey, emphasized the link between consumption and personal defects, while at the same time embracing the centrality of contagion, stating consumption,

With all its malignity and catching nature … may be connumerated with the worst of Epidemicks, since next to the Plague, Pox, and Leprosie, it yields to none in point of Contagion … Moreover nothing we find taints sound Lungs sooner than inspiring the breath of putrid, ulcer’d, consumptive Lungs; many having fallin into Consumptions only by smelling the breath or spittle of Consumptives, others by drinking after them; and what is more, by wearing the Cloathing of Consumptives, though two years after they were left off.3

Despite his strong inclination toward contagion, Harvey also wrote that the disease often passes “from Consumptive Parents to their Children,” and as such, it is “Hereditary, insomuch that whole families, sourcing from tabefyed progenitors, have made their Exits through Consumptions.4

By the end of the seventeenth century there were growing doubts about the validity of contagion theory. In northern Europe, physicians used the evidence that the disease was often relentless and widespread in some families as proof that consumption was the result of a hereditary constitutional defect.5 By the eighteenth century, there was a definitive split in the belief over the contagiousness of tuberculosis between southern and northern Europe, with a refusal by many in northern Europe to acknowledge the possibility consumption was contagious.6 In Britain, by the nineteenth century, there was a strong denunciation of the contagion theory as lacking empirical evidence. A Treatise on Tuberculosis (1852) stated:

The doctrine of contagion has, however, at all times been based on very vague and insufficient evidence; such as isolated cases of the disease in individuals who had previously been in constant attendance upon the sick; or in husbands or wives, where both had slept in the same bed until the fatal termination of the disease in the one first affected … Against the few facts which tend to support the doctrine of contagion, there are tens of thousands against it.7

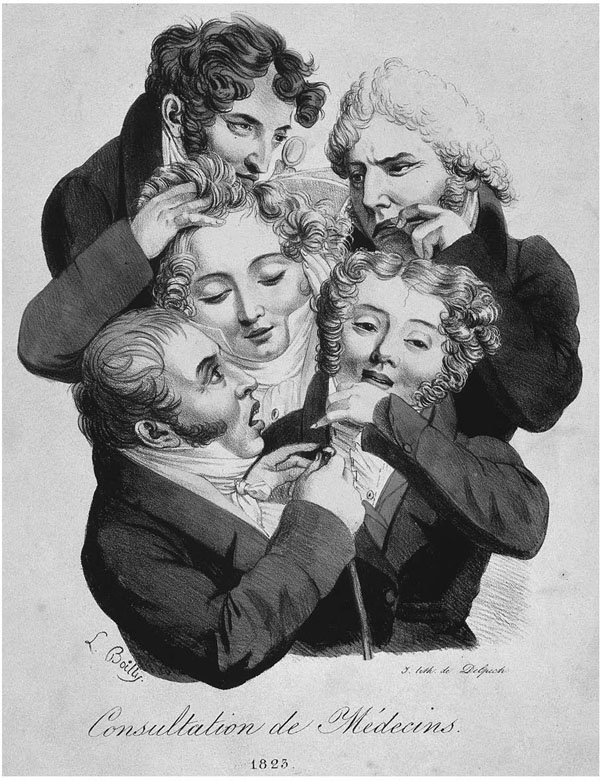

Figure 2.1 A group of young, fashionable doctors. Lithograph by F-S. Delpech after L. Boilly, 1823. Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

The disavowal of contagion necessitated the development of other explanative schemes, and the concept of heredity was incorporated into the theoretical repertoire of causation. By the early nineteenth century, many investigators were persuaded that conditions like tuberculosis, gout, and insanity were the end-product of a multifaceted etiology stemming from the action of some murky grouping of environmental factors and influences. Yet fierce debates continued over the various explanations for tuberculosis, ranging from contagion to heredity and from the constitution to the environment. The general consensus was that the blame rested with some inborn susceptibility.8

While the anatomico-pathological approach was gaining popularity, a constitutional predilection toward infirmity became the predominant explanation for a variety of chronic illnesses, tuberculosis among them. In 1806 John Reid plainly stated the constitutional case.

There is however … an acknowledged variety in constitutional tendency to genuine phthisis, from whatever source it may originate. The destroying angel, while requiring general retribution for certain deviations from nature, marks particular individuals for primary sacrifice. Although no one ought fearlessly to expose himself to the causes of consumption, every one has not an equal cause for fear … Natural organization, age, sex and professional or other occupations and habits, may, perhaps, be made to include every peculiarity of disposition to pulmonary consumption, whether native or adventitious; or, in the language of systematics, will comprehend the praedisposing and exciting causes of this formidable and destructive malady.9

The “constitutional construction” proposed the body was an ordered structure whose fundamental characteristics were inherited as a whole, resulting in either a strong constitution that was resistant to disease or a weak one that left an individual vulnerable to illness.10 By placing the constitution at the heart of the explanatory process, physicians crafted a physiological hypothesis of causation that led to the belief that little could be done to correct any inborn constitutional imbalance.

Gradually, certain afflictions came to be intricately tied to hereditary concepts. Horace Walpole (1717–1797) reminisced about the effects of a weakened constitution on his family and his own trials as a child, stating: “[I] was extremely weak and delicate, as you see me still, though with no constitutional complaint till I had the gout after forty, and as my two sisters were consumptive,11 and died of consumptions, the supposed necessary care of me (and I have overheard persons saying, ‘That child cannot possibly live’) so engrossed the attention of my mother, that compassion and tenderness soon became extreme fondness.12 Medical practitioners believed an inherited malady was embedded in the constitution of an individual and could manifest in a variety of ways, as in the Walpole family as both consumption and gout. (See Plate 7.) In his Treatise on Pulmonary Consumption, Sir James Clark identified the importance of the constitution: “Before we can hope to acquire an accurate knowledge of consumption, we must carry our researches beyond the pulmonary disease, which is only a secondary affection, the consequence of a pre-existing constitutional disorder, the necessary condition which determines the production of tubercles.13

In nearly all of the debates over hereditary disease, the connections between the constitution and heritable disease are plainly evident; but the actual importance of the theoretical web becomes clear when one takes into account how physicians viewed the constitution.14 Doctors seeking to explain the resistance of certain illnesses—such as tuberculosis, madness, or insanity—to treatment or cure had few options. Reliance solely upon environmental influences and lifestyle, failed to account for the implacability of these illnesses in the face of behavior modification and changes in environmental conditions, which usually produced no permanent improvement. In intertwining chronic illness and the constitution, physicians were able to account for their failure to affect the outcome of diseases like consumption and by maintaining these illnesses were constitutional, physicians were also inclined to view them as hereditary.15

Hereditary rationalization carried weight in situations where the disease carried off entire families and when only some individuals were affected, as it was the consumptive constitution that was passed down and not the illness itself. As Thomas Reid argued in 1782, “This disease usually attacks people of a delicate, weak, tender constitution and, as such habits of body are peculiar to certain families; in such cases, it may be with some truth termed an hereditary disease.16 Consumption was particularly notorious for running through families, like the Brontës, where, tragically, one member after another perished successively of the disease. (See Plate 8.) The two oldest sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, died in 1825 from tuberculosis. They were followed to the grave by Branwell (1848), Emily (1848), and Anne (1849), all of whom perished from consumption. Charlotte passed away in 1855, also believed to be from a tubercular condition complicated by her pregnancy.17 In January of 1849, Charlotte wrote: “Since September sickness has not quitted the house. It is strange it did not use to be so, but I suspect now all this has been coming on for years. Unused, any of us, to the possession of robust health, we have not noticed the gradual approaches of decay; we did not know its symptoms: the little cough, the small appetite, the tendency to take cold at every variation of atmosphere have been regarded as things of course. I see them in another light now.18 In 1836, Emily Shore remarked on one such family that seemed to be afflicted with a rapidly progressing galloping consumption.

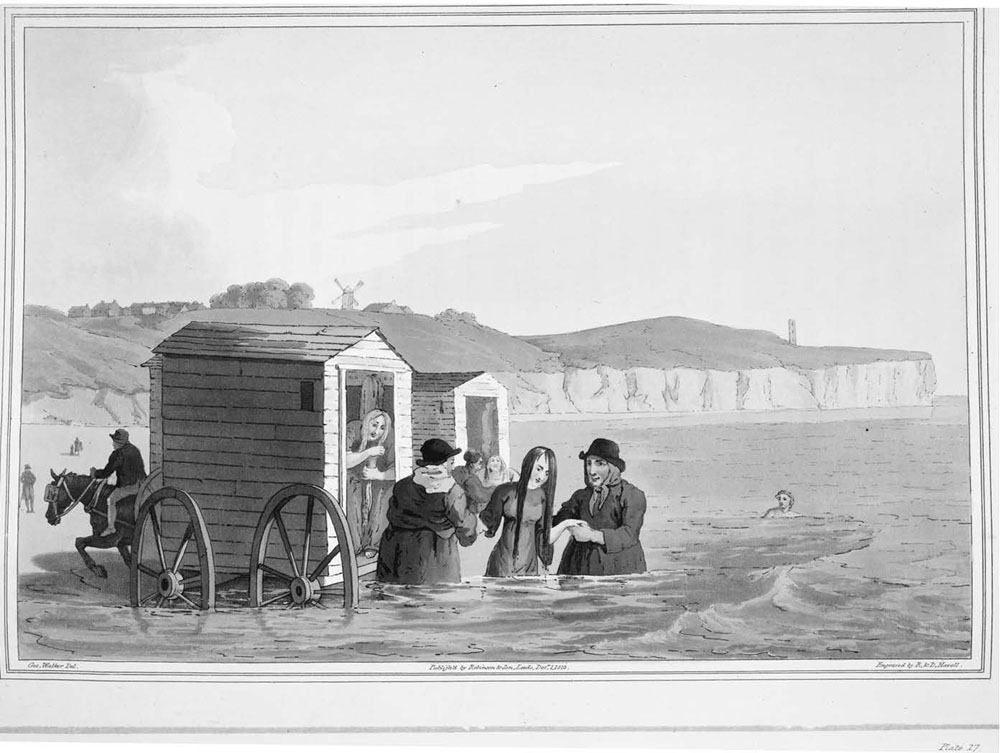

Figure 2.2 Sea-bathing was often prescribed for those with delicate constitutions. “Sea bathing.” George Walker, Costume of Yorkshire (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1813). New York Public Library Digital Collections [accessed June 14, 2016].

The bathing women … told mamma a few particulars about the family at No. 36. It seems that there is a great mortality among them. As soon as they arrive at the age of twenty they die. The one whose hearse we saw was the fourth of them thus prematurely cut off, and one of them now is expected to have her turn—apparently the pale one, the elder of the two. What they die of we could not make out; probably consumption, though it seems to be a very rapid one.19

The frequency of this sort of occurrence, where multiple members of a household suffered from consumption or where entire families perished from the illness, led to the supposition in much of northern Europe that the malady was the consequence of inheriting a flawed constitution.20 The constitutional construction also provided a convenient explanation for situations where only one member of a family died, as it could be claimed that the victim was the only member to inherit the weak constitution. Nineteenth-century medical practitioners and lay persons alike accepted that consumption was fundamentally an expression of an individual’s family legacy and personal circumstances. As J. J. Furnivall wrote in 1835:

There can now be little doubt, “that the Tubercular Diathesis is in direct proportion to the development of this peculiar constitution,” and that the deposition of tubercles is in persons, hereditarily predisposed, much favoured by, and in other, mainly dependent on, a deviation from healthy innervation … [which] leads directly to the formation or localization of tuberculous matter.21

Heredity and constitutional predisposition, combined with adverse climatic circumstances and living conditions, seemed to provide a convincing substitute for contagion. Physicians argued that if tuberculosis were contagious, everyone in the home would be suffering from the illness. As On the Nature, Treatment and Prevention of Pulmonary Consumption stated:

Consumption is not communicated by any infection, any contagion, any more than a fractured limb is so communicated. It may very well happen however, that persons belonging to the same family, living in the same apartments, exposed to the same deteriorating influences, at once producing the malady and rendering it inveterate when produced, shall in succession be seized with phthisis, so that whole families, as has too often happened, shall be carried off by it. This it is, which has led to the belief not only of the communicability of phthisis from person to person, but also of its transmission in families.22

The chief ideological link between notions of the constitution and heritability was not without its contradictions. Although consumption had a penchant for running through families, it did not do so with any predictable consistency. As Thomas Bartlett described in 1855, “As with gout, so with Consumption, it is often found that the disease spares one or two generations, only to appear again in the succeeding ones.23 To counter this hurdle, the concept of a hereditary predisposition was introduced. This notion provided a theoretical bridge, suggesting that an individual did not inherit the actual disease but instead an inclination or tendency toward the illness, which would only develop under the correct environmental conditions and stimuli.24

To account for the role of an innumerable variety of exciting causes in disease, the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw the rise to prominence of the disease diathesis. In most cases, the term diathesis was used to denote a predisposition to a disease; however, it was also sometimes used to describe an injury to the body which became permanent and was then passed down as the predisposition. As a result, the diathesis could be both the acute injury that created the predisposition, or the predisposition itself.25 Hereditary sickness emerged as a by-product of the constitutional construction of disease, as a diathesis could either be inherited or acquired during the course of life. In some conditions, such as gout, the diathesis was first thought to be acquired and then passed on. John Murray’s A Treatise on Pulmonary Consumption addressed the role of parental conformation in the development of hereditary illness, arguing, “As to parentage—the offspring of scrofulous and consumptive, dyspeptic, or gouty parents, will be born into the world with constitutions susceptible of those external agencies which conduct to confirmed Consumption; it is in this way only that Consumption can be said to be hereditary; and thus literally may the ‘sins of the fathers be visited on the third and fourth generation.’26

Differences in constitution provided the explanation for the variations observed in mortality rates and in the ways a disease progressed in each individual case. The extensive impact and variable mortality of consumption fueled the search to identify the “tubercular diathesis” and the characteristics that led to a person’s innate susceptibility to it.27 The repeated assaults on a victim’s person made by chronic illness had hereditary ramifications, since only recurring actions resulted in a permanent change to the constitutional composition of the body. In 1799 William Grant argued a disease could only become transmissible if widespread alterations occurred in the constitution of the afflicted individual. Similarly, in the early nineteenth century, Horatio Prater argued, “The grand distinction between hereditary and non-hereditary diseases seems to be that the former alter the structure deeply and permanently … while the latter affect every part superficially.28 These statements illustrate one of the persistent problems associated with hereditary diathesis—that of defining the exact circumstances under which an illness could result in an overwhelming change in the constitution. The customary response by medical practitioners was an assertion of the importance of the length of the insult. By the nineteenth century, the term “diathesis” had come to refer primarily to chronic rather than acute conditions, particularly those illnesses that either intermittently or progressively exerted an influence on the victim, such as asthma, gout, cancer, epilepsy, insanity, and, of course, consumption.29

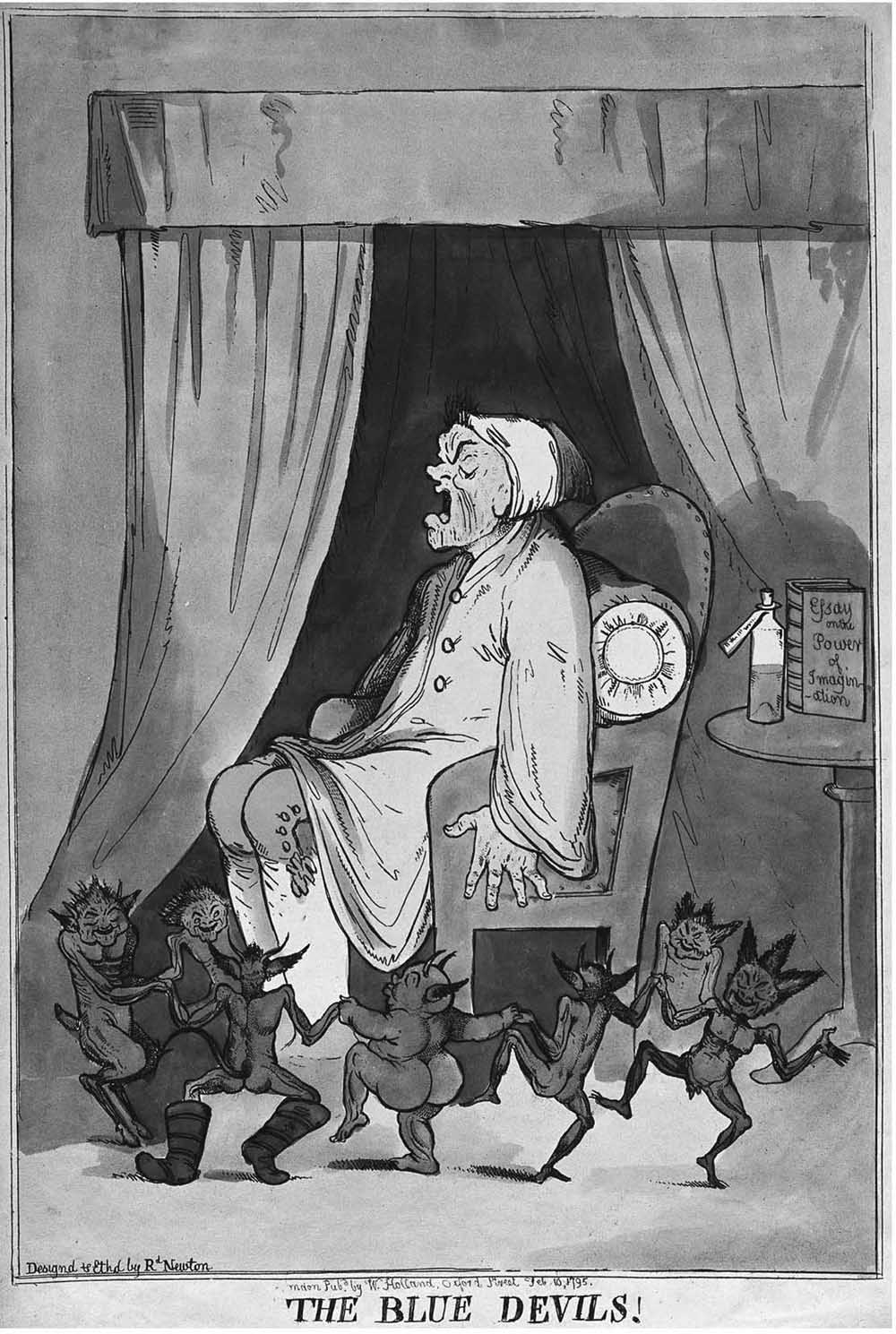

Figure 2.3 A man suffering from gout (represented by a group of dancing blue devils). Richard Newton (London: W. Holland, 1795). Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

Beginning in the late eighteenth century and continuing well into the nineteenth, the hereditary explanation of chronic disease became practically universal, touted in medical treatises, nosologies, and textbooks. In 1834, for example, James Clark summed up the feelings on the subject of heritability and tuberculosis, arguing that it was not the disease that was inherited but rather a constitutional predisposition to it. “That pulmonary consumption is an hereditary disease, in other words that the tuberculosis constitution is transmitted from parent to child, is a fact not to be controverted; indeed, I regard it as one of the best established points in the etiology of the disease.30 Physicians believed that once a chronic disease was firmly established, it was extremely difficult if not impossible to dislodge making hereditary illness synonymous with incurability. The irredeemable nature of these sorts of diseases turned the focus toward prevention rather than cure, and hope in these cases rested on averting the establishment of the diathesis.

As a chronic disease, tuberculosis was located in a framework of predisposition and incurability. Thus, when an 1827 article in The Lancet proposed the question “But can consumption be cured?” the answer was inevitable. “Odd bless me, that’s a question which a man who had lived in a dissecting room would laugh at … for there is no case which, when it has proceeded to a certain extent, can be cured.31 It was widely believed there was little that could forestall the development of consumption in those possessing the predisposition. The best advice many nineteenth-century medical investigators could proffer was to be born into a family that had no history of the illness. Furthermore, they determined that the origin and pattern of development for phthisis could be a function of the individual’s sex, ethnicity, occupation, status, living conditions, or any combination of these factors. In 1808 the Treatise on Pulmonary Consumption stated:

There is nothing absurd in supposing, that the lungs may be often so deficient from their original structure, and such deficiency appears to me to be the only effect of mal-conformation which gives occasion to the disease. Those means which enfeeble the general system, as bad food, excessive venery, vicissitudes of weather, cannot predispose to consumption of the lungs more than to that of any other vices, the predisposition must have been antecedent to their agency.32

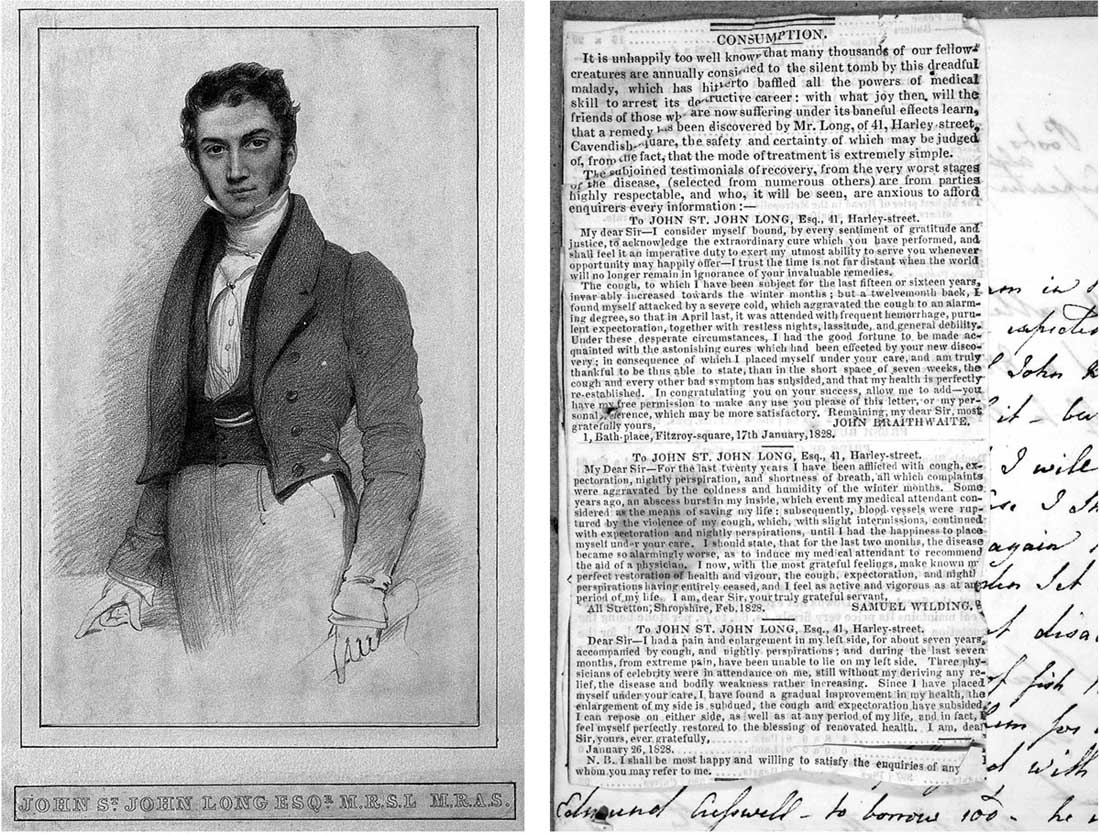

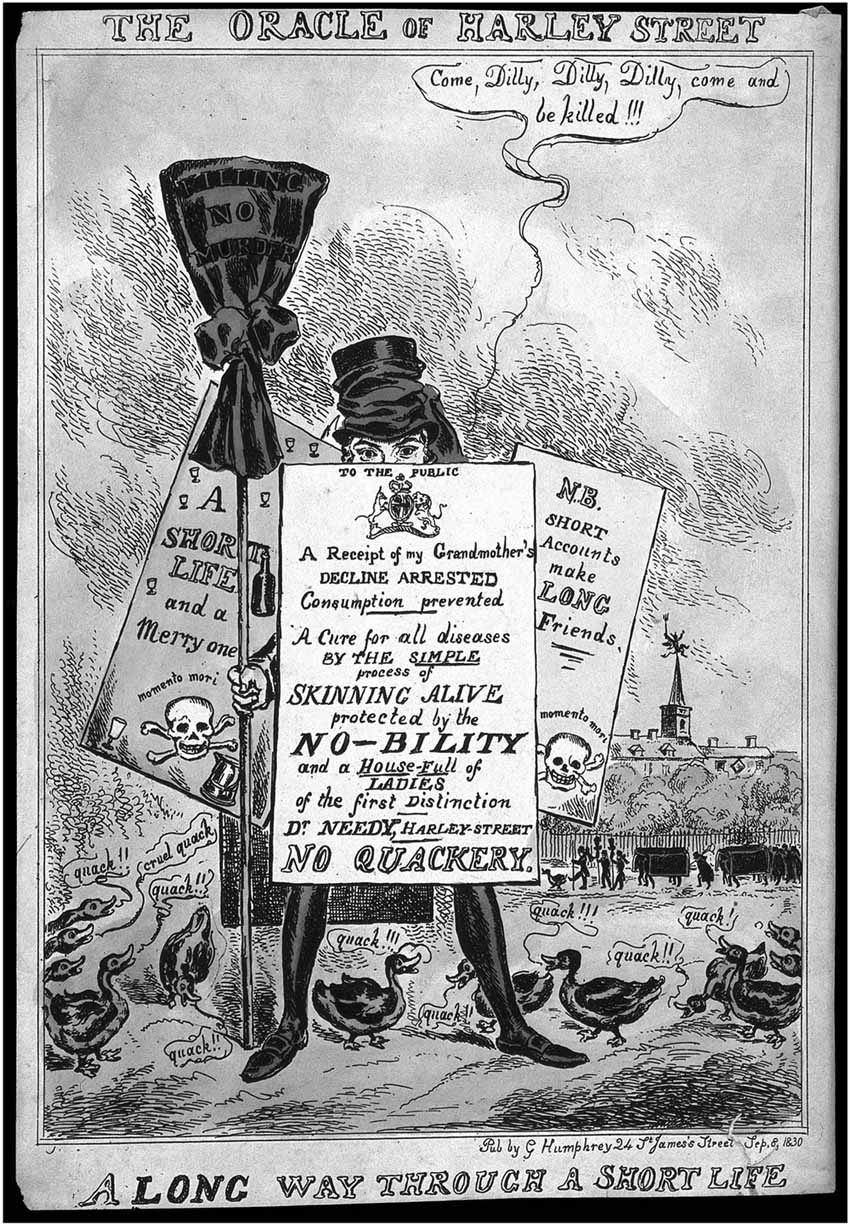

Complicating the issue of predisposition was the fact that nineteenth-century medical professionals held little hope for a cure once the disease was established, leading to widespread dissatisfaction over the available treatment options. Quack treatments were a constant concern, as unscrupulous individuals purported to have cures for consumption, while desperate victims, like Miss Cashin, were often willing to try anything. This young lady, fearing she might come down with consumption, submitted to a treatment by the quack physician Mr. John St. John Long. He performed a procedure that included rubbing her back with a corrosive, which caused a tremendous sore that then became infected and caused her death in October of 1830. St. John Long was tried and convicted of manslaughter, though escaped imprisonment and instead was fined 250 pounds.33

Consumption’s extended, and seemingly invisible, period of incubation and vague symptoms often led to routine misdiagnosis until the final stages of the illness. Once the disease was plainly evident, the patient had passed the stage at which medical authorities believed they could affect any alteration. In a letter of condolence to a father who recently lost his daughter to consumption, the author addressed these difficulties.

I heard nothing of the heavy calamity that you have sustained till the day before I received your letter … nor indeed did I apprehend that there was much danger. Your Physicians failed, but I believe in disorders where the lungs are much affected, physical aid will scarcely ever avail.34

Purported cures and positive outcomes were generally believed simply to have been cases of curable maladies misdiagnosed, and the effective treatment explained as the result of confusion with another more tractable disease.

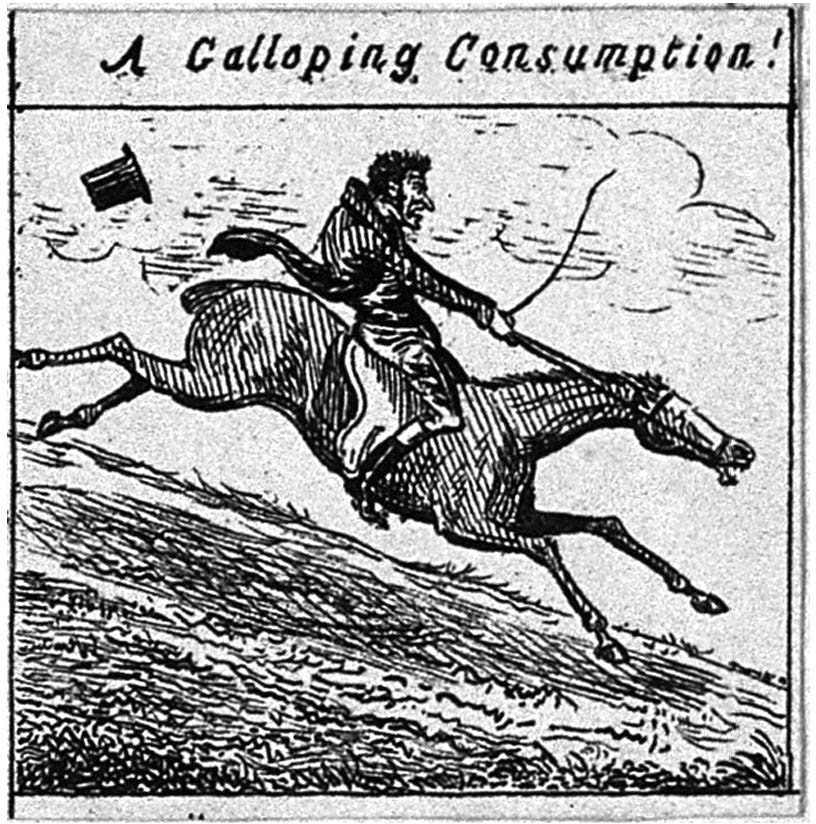

The seemingly infinite variety of symptoms led to a plethora of terms for, and types of consumption. The illness could be galloping (a rapidly progressing pulmonary form) or, as William Black described it, “galloping the patient to a skeleton in a few months.35 More typically, however, it developed slowly, with seemingly insignificant or vague symptoms in its early stages. The most common first sign, a chronic cough, was frequently accompanied by pallor. As the illness advanced, the victim developed a loss of appetite and weight. Further indicators included a persistent low-grade fever and night sweats. As the disease progressed, its victims typically presented a combination of symptoms, including a deep cough, wheezing, shortness of breath, a pain in the side, and a low-grade intermittent “hectic fever” which produced a “hectic flush” upon the cheeks. In the advanced stages, the consumption became increasingly visible and the sufferer exhibited signs of emaciation. The eyes became glassy and appeared large as they sank in their orbits, and the cheek bones became prominent. The shoulders elevated and the clavicles projected, forming the characteristic wing-backed appearance. The consumptive was also afflicted with night sweats, loss of strength, debility, and frequent darting pains in the chest or stitch in the side, a rapid pulse, and constipation.

Figure 2.4 Portrait of St. John Long and a Letter from a Consumptive stating “I think it worth your attention” that includes advertisement for the services of St. John Long (1828). John St. John Long. Lithograph. Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

Figure 2.5 St. John Long dressed as a funeral mourner surrounded by ducks and placards advertising the malpractice cases of his in which patients died. “The Oracle of Harley Street.” Colored etching by Sharpshooter (?) (London: G. Humphrey, 1830). Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

The illness was revealed in the skeletal appearance of its victim, with drawn features and a protruding bone structure. In the latter stages the “hectic fever” intensified, cycling more strongly in the evening hours. The increasingly frail body was wracked by evermore intense fits of coughing, signifying the disintegration of the patient’s lungs, a circumstance made even more evident by the appearance of hemoptysis (expectoration of blood and other debris). As the disease advanced, the cough became incessant and was attended with an inclination to vomit; the patient’s voice became hoarse, the teeth whitened, and the veins became prominent, the pain in the chest increased, the breathing became more labored and the expectoration of purulent matter also increased until finally ended by the patient’s death.

Even when properly diagnosed, the majority of physicians and lay individuals saw it as an affliction with no hope of recovery. In 1840, George Bodington expressed the helplessness and frustration experienced by doctors when faced with consumption, writing, “Whilst little had yet been done, by way of improvement, in the treatment of the disease: consumptive patients are still lost as heretofore; they are considered hopeless and desperate cases by most practitioners, and the treatment commonly conducted upon such an inefficient plan as scarcely to retard the fatal catastrophe.36 Accompanying the concern over curability was a widespread dissatisfaction with the available options for treating consumption. Discussions of the current therapies could even be found in The Magazine of Domestic Economy (1840) which provides a glimpse of the helplessness the disease engendered in its victims and their families. “Although many nostrums have been from time to time promulgated, and asserted cures for this fatal disease advertised the most respectable of the faculty have long since abandoned all hope from any remedy that medicine can effect.37 This bleak prognosis reinforced the importance of prevention, but there remained a growing stable of treatments, as no medical practitioner would simply let the disease progress without making any attempt to affect its outcome.

Figure 2.6 Caricature of “A Galloping Consumption.” Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

The uncertainty of diagnosis and prognosis narrowed the field of action for the medical practitioner and the victim alike. The consequence was the development of a practical approach to treatment. The management of consumption tended to rest on the experiences with the illness, some dating back to the ancient period, with a corresponding set of traditions and procedures. The most durable prescription was for horseback riding, a therapy popularized by Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689), and one that remained standard long after his death. Sydenham argued that gentle horseback riding was an exercise that provided the correct stimulation for the consumptive, by the dual benefit of exposure to the open air and by strengthening the weakened constitution without overtaxing the system.38 Riding remained a method for managing tuberculosis well into the nineteenth century.

Sydenham’s eighteenth-century successors extended the premise of horseback riding and promoted the beneficial effects of movement by proposing alternative treatments that achieved the advantages of motion. For instance, in 1787 James Carmichael Smyth touted the positive benefits of swinging, arguing it was a mechanism of motion completely “independent of any muscular exertion.39 For Smyth swinging also furnished an accessible alternative that mimicked the positive results of sailing by providing the benefits of a sea voyage without any of the nasty side effects, like seasickness. (See Plate 9.) Though there was an acknowledged advantage to be gained from sailing, like almost every other aspect surrounding tuberculosis, there was no consensus on the exact nature of that benefit, a circumstance Smyth himself admitted. He conjectured it was the motion achieved during sailing that had “an immediate effect in removing, or at least in suspending the action of coughing,” and it was this very motion that swinging duplicated.40 There was certainly a belief in the effectiveness of sailing in mitigating the effects of consumption. In 1838, a young woman sailing to Spain in hope of restoring her health, wrote, “I continue to be an excellent sailor, and enjoy myself thoroughly on board. My cough is almost gone, and I never wake up feverish and throbbing as I did in England. Really I shall hardly be an invalid when I reach Madeira.41

Treatment for consumption was generally limited to recommending a lifestyle and climate conducive to slowing the relentless progress of the illness. One of the most enduring therapies involved removing the patient to a warmer climate. This prescription usually included residency in temperate, sunny surroundings, believed to have the ability to retard the devastation of the lungs that otherwise led to death.42 King George III reflected the contemporary hope, writing, “in consequence of the Chief Baron’s going to Lisbon with his Eldest Daughter whose health requires the change of Climate. The King … desires the Lord Chancellor will acquaint the Lord Chief Baron how ardently He wishes that the Sea Voyage and Mild Air of Lisbon may prove advantageous to the Young Lady.43 In 1818, John Armstrong addressed the advantages of sailing when combined with removal to a warmer climate. “The best thing that can be done for one in whom pulmonary consumption is suspected, or actually existent in an incipient state, is to send him immediately to a warm climate; and the voyage to the place of his destination should be made rather long, than short, as sailing upon the sea is very useful on many occasions.44 One such consumptive was Emma Wilson, who chronicled her Italian travels as well as her illness, writing:

Time gets on, but I find no improvement in my health, I daily become weaker, and all my bad symptoms increase rather than diminish. The Celebrated Dr. Stewart is just arrived at Rome … he was the first Inventor of the strengthening System in Consumptive Cases … he thinks me very Ill & hopes to make me soon better under his Strengthening System, but I cannot fill my Journal with an account of how many Pill’s [sic] I take.45

The benefits of warm, sunny, dry climes remained popular and a move to a more amenable climate continued as an integral part of the therapeutic approach to tuberculosis.

One of the most influential nineteenth-century proponents of climate change was Dr. James Clark. In 1818, Clark accompanied an advanced consumptive to the south of France for treatment, his continental travels inspired his writings and, by 1820, led to a comparative investigation of the medical institutions, climates, and prevalent diseases of France, Switzerland, and Italy. Within a decade, he extended this research to include recommendations on the cure and prevention of chronic complaints and on the role of climate in chronic illness.46 Clark established a successful practice in Rome, where he treated wealthy English men and women (including the poet John Keats) who sought respite from their illnesses.

Clark’s significant and well-received A Treatise on Pulmonary Consumption (1835) focused on prevention. He was the first person to not only systematize all of the known information on the disease, but also to make it available to the general public. His work had the added benefit of helping him be appointed as physician to Queen Victoria in 1837.47 Clark’s influence is reflected in George Bodington’s An Essay on the Treatment and Cure of Pulmonary Consumption: “As regards the causes, origin, and nature of the disease, the work of Sir James Clark, who reaped advantage from the labours of Carswell and other pathologists, is complete and satisfactory.48 Bodington, however, took issue with Clark’s failure to present a comprehensive plan of treatment and argued that he neglected to advance the model of consumption, admonishing the doctor for “leaving the matter, upon the whole, pretty much in the same state he found it.49

In 1841, Clark published The Sanative Influence of Climate, which offered explicit travel directives for those suffering from consumption and even went so far as to distinguish between the relative advantages of the weather conditions in Nice versus Rome and Madeira versus Pisa.50 A number of medical investigators used climate as an explanation for the differences observed in the patterns of disease between countries. Comparisons of the behavior of consumption in different geographic locations littered the medical treatises, as did evaluations of its variable impact on certain ethnicities. By way of explanation, “climate” was broadened to include the role played by fluctuations in that climate. This variation came to be considered one of the most significant reasons for the prevalence of consumption in England.

There was also a growing group of drugs and restoratives thought to target certain symptoms of consumption. The focus on therapeutics to allay the effects of tuberculosis, rather than on eradication, was partly the result of the late-stage diagnosis. At this point, symptomatic relief received primacy, as cure was thought impossible.51 The popularity of certain treatments rested on their ability to ease the patient’s ordeal. Many believed that “in a hopeless disease, we are justified in resorting to new expedients when the old ones fail us.52 It was not uncommon for some of these new treatments to be mentioned alongside tried and true methods. In 1832 a clinical lecture published in The Lancet described one physician’s attempts to treat the symptoms of tuberculosis:

About nine years ago, a young married lady, who had two children, came under my care with all the symptoms of confirmed consumption, cough, and muco-purulent expectoration. She had occasionally spit a little blood; there were night sweats and colliquative diarroea. I supported her strength with animal food, and some fermented liquor, whenever her pulse could bear it; gentle exercise in the open air, and free admission of air into her rooms. I restrained the diarrhea by catechu, longwood, and sometimes opiates; sometimes applied half-a dozen leeches and blisters, and gave digitalis for a few days, when there was appearance of acute inflammation; sometimes gave bark and soda, sometimes quinine with diluted sulpuric acid, which restrained the sweats.53

This account provides just one example of the infinite combination of treatments—both passive and active—employed against consumption. The management of diet, the patient’s environment, and the prescription for rest, even having the patient suck chipped ice in an effort to alleviate hemoptysis, were all measures pursued alongside more invasive courses of action, including the application of a variety of therapeutic agents. Asses’ milk was a popular component of the consumptive diet, and at one time Thomas Young prescribed a specific daily course of one half pound of suet rendered from mutton as a therapy.54 Opiates were also commonly employed to assuage the cough and pain customary in the final stages, and though bleeding had waned in popularity, it and the practice of cupping continued, as did the use of leeches.55 (See Plates 10 and 11.) Other chemicals and therapeutics utilized in treating the various symptoms included calomel, iodine, cod-liver oil,56 quinine, salicylic acid, digitalis, lead acetate, a variety of emetics, potassium nitrate, antimony sulphate, boracic acid, and creosote, to name a few.57

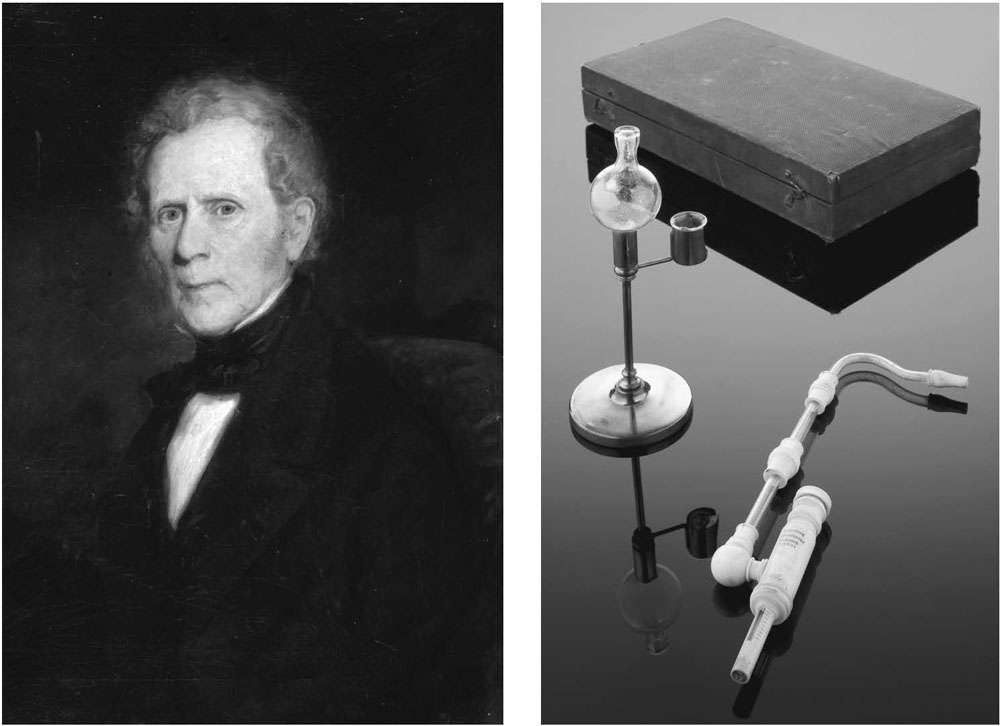

The number of patent medicines steadily grew during the nineteenth century, and an assortment of anti-consumptive agents became available to the public. Additionally, medical practitioners developed a variety of inhalation therapies in an effort to tackle the fundamental unit of pathology—the tubercle. These treatments included the inhalation of a variety of balsams, astringents, and resins. In 1823, Sir Alexander Crichton argued for the efficacy of inhaled tar in treating tuberculosis: “The hope which I, in common with a few others, have of late years held out of the curability of consumption, arose entirely from experience, especially for the efficacy of tar vapour and temperature.58 In the 1830s, the inhalation of iodine vapor became especially popular; later, carbolic acid, creosote, and sulphuretted hydrogen enjoyed acceptance as inhalants.59 Although treatments were plentiful, there remained a consensus that consumption was “A disease which … no remedies in our present state of knowledge can subdue, and which generally leads to a fatal termination.60

Figure 2.7 Sir Alexander Crichton and Iodine Inhalation Apparatus. Left: Sir Alexander Crichton. Right: French iodine inhalation apparatus for the treatment of tuberculosis, unknown maker c.1830–1870. Science Museum, London, Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

In the absence of a medical solution, a social one developed, and the attention turned toward prevention which, like everything associated with consumption, was less straightforward than one might have hoped. There was no clear division between the environmental and hereditary causes of tuberculosis; instead, the explanations remained tangled. Generally, an inherited susceptibility was thought to be complicated by an exciting cause, leading to the creation of an acute or persistent illness, which in turn, amplified the likelihood of further illness by magnifying an individual’s susceptibility.61 The hereditary constitution, an individual’s physiological fitness, and the quality of the environment, as well as any other strains provided by lifestyle, continued as prominent themes in the working knowledge of the disease.