In 1855 Thomas Bartlett asserted that “Consumption is a disease which is no respecter of persons; for it seizes alike both upon the high and the low, there being no social position bestowing an exemption from its attacks. There is privilege neither of caste nor sex; and there is no immunity for age, for all … are subject to the inroads of this terrible disease.1 Despite its ubiquity, consumption did not serve as a unifying force, rather it was the subject of numerous discourses and constructed categories of perception and victims were “othered” accordingly. The oppositional representations went beyond a dichotomy between the healthy and diseased body, and included internal differentiations along class and gender lines within the community of sufferers. As Clark Lawlor and Akihito Suzuki argue “consumption becomes a marker of individual sensibility, genius and general personal distinction as the eighteenth century progresses: its heightened representation in literature and art reflects, and to some extent reinforces, its perceived cultural value to the self.2

In the nineteenth century, consumption was characterized by two distinct and seemingly unrelated discourses, in which victims from the more prosperous classes were lauded while poorer victims were stigmatized. The management of the malady varied with social status and, in many respects, was treated as a different entity, depending upon the quality and character of its victim. The understanding that tuberculosis was partially linked to social status was crucial in determining the individual’s way of life and, as such, his or her environment. Environment became the predominant explanation for tuberculosis in the working classes. This, in turn, fostered a negative perception of the illness in these groups. Instead of victims, members of the lower orders were presented, by social reformers and medical investigators, as the architects of their own demise. In the more prosperous classes, by contrast, consumption was primarily viewed as the consequence of a hereditary defect, one complicated by exciting causes. This more benign presentation of the disease only offered the affluent victim limited control over the circumstances that provoked the illness. Among the lower classes the tubercular diathesis was seen as the result of poor air quality, drunkenness, or material deprivation, all of which were hallmarks of their life circumstances. Given that phthisis was primarily conceptualized as an urban condition, due to its heightened visibility in cities, it logically followed that there was an increased susceptibility to the illness owing to the unhealthy nature of life in the metropolis.3

As individuals migrated from rural districts into larger towns and cities searching for work, they encountered living and working conditions that created the perfect environment for sickness to flourish. On this basis, Friedrich Engels argued that living and working situations were responsible for the high incidence of consumption.

That the bad air of London, and especially of the working-people’s districts, is in the highest degree favourable to the development of consumption, the hectic appearance of great numbers of persons sufficiently indicates. If one roams the streets a little in the early morning, when the multitudes are on their way to their work, one is amazed at the number of persons who look wholly or half-consumptive. Even in Manchester, the people have not the same appearance; these pale, lank, narrow-chested, hollow-eyed ghosts, whom one passes at every step, these languid, flabby faces, incapable of the slightest energetic expression, I have seen in such startling numbers only in London, though consumption carries off a horde of victims annually in the factory towns of the North.4

Workers faced inadequate housing, insufficient food, and physical toil; circumstances that combined with heavily crowded surroundings in workshops, unhygienic living conditions, and physical and material hardship to provide the perfect setting for the rapid development and proliferation of tuberculosis as well as other devastating illnesses.

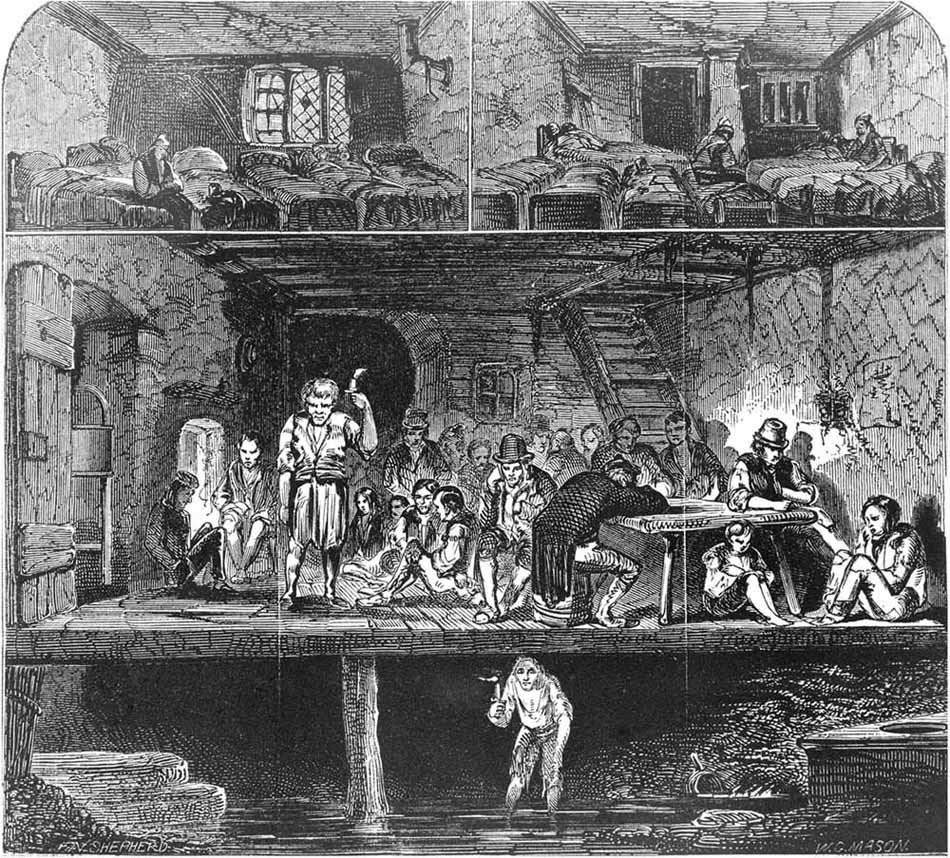

Responsibility for outbreaks of a variety of diseases rested with the crowded and horrendous conditions of urban living. Slums were presented as sites of corruption—the antithesis of the open spaces, fresh air, and sunlight peddled by physicians as beneficial in forestalling and treating tuberculosis. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine addressed the importance of the environment to the health in 1839.

Figure 3.1 “Lodging House in Field Lane,” Hector Gavin, Sanitary Ramblings (London: Churchill, 1848). Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

The Prime essentials to human existence in crowded cities are pure water, pure air, thorough drainage, and thorough ventilation … [and] the facility of taking exercise within a convenient distance. Thus, every city has its public pulmonary organs—its instruments of popular respiration—as essential to the mass of the citizens as is to individuals the air they breathe.5

The article highlighted the pertinent physical causes of illness: water, air, sanitation, ventilation, and physical activity, all of which were emphasized time and again in works on tuberculosis.

Consumption could result from any number of internal or external factors including malnutrition, foul air, and emotional misery, all of which were capable of inducing a diathesis.6 Although these conditions seemed to satisfy investigators seeking to rationalize the abundance of tuberculosis in the working classes, they did little to account for the simultaneous occurrence of lethal consumption among the privileged orders. Thomas Beddoes addressed the impact of the illness in the upper reaches of society.

It would perhaps be possible to approximate towards an estimate of the number of British families in opulent circumstances, infested by this disease. The members of the two houses of parliament, who have lost either father, mother, brother, sister or child, by consumption, could, I suppose, be ascertained without much difficulty. Now the proportion would probably apply pretty nearly to the gentry at large, their respective habits and constitutions not being materially affected by the difference in wealth.7

The roles of injury and inactivity were applied to the upper classes suffering from consumption.8 Robert Hull admonished the wealthy for what he saw as an emulation of the less fortunate, who were without choice.

Why should the untethered rich imitate the necessities of the poor? Why should parents, to whom heaven gives the means for flight from undrained houses and lands, reside in the foul atmosphere of crowded cities? In streets, in alleys? Why should a generous nourishment be prohibited to those, whose purses can command it? All agree that scrofula and consumption, a form of scrofula, predominate among the poor. Then they are results of those circumstances, wherein the poor differ from the rich. What are these? Chiefly impure air, scanty food, neglected excretions. Yet the rich incarcerate their consumptives in azotic chambers; keep them low, as if decline were active inflammation; lose sight of the abdominal apparatus and its most potent secretions, as if the lungs, which depend upon the belly within and the atmosphere without, were isolated perfectly from both.9

The writings on consumption overwhelmingly presented women of the upper orders as more liable to phthisis than men, largely because of the constraints society placed upon them. Middle- and upper-class women became consumptive by virtue of their inactive lifestyles. As Beddoes remarked, “In opulent families, I impute it in great measure to the indolence of females, that they so much more frequently become the victims of consumption.10 He even went so far as to raise the power of inactivity to incapacitate above that of air contaminated by small particulate matter.11 The dissipations that marked the luxurious lifestyle of the wealthier classes were also dubbed significant causes of consumption.12 In 1832, Charles Turner Thackrah argued “the effects of professional life on the physical state of the upper orders, as produced by their pursuits and habits, are so familiar to a medical practitioner, as to require no direct investigation. They are not, however, the less important. The evils, indeed, of a too artificial state of society are more strongly marked in the upper than in the lower classes.13 Although poverty and its attendant lifestyle could lead to tuberculosis, the indolent and inactive lifestyle of the wealthy also became one of the most touted causes of consumption, particularly among women.

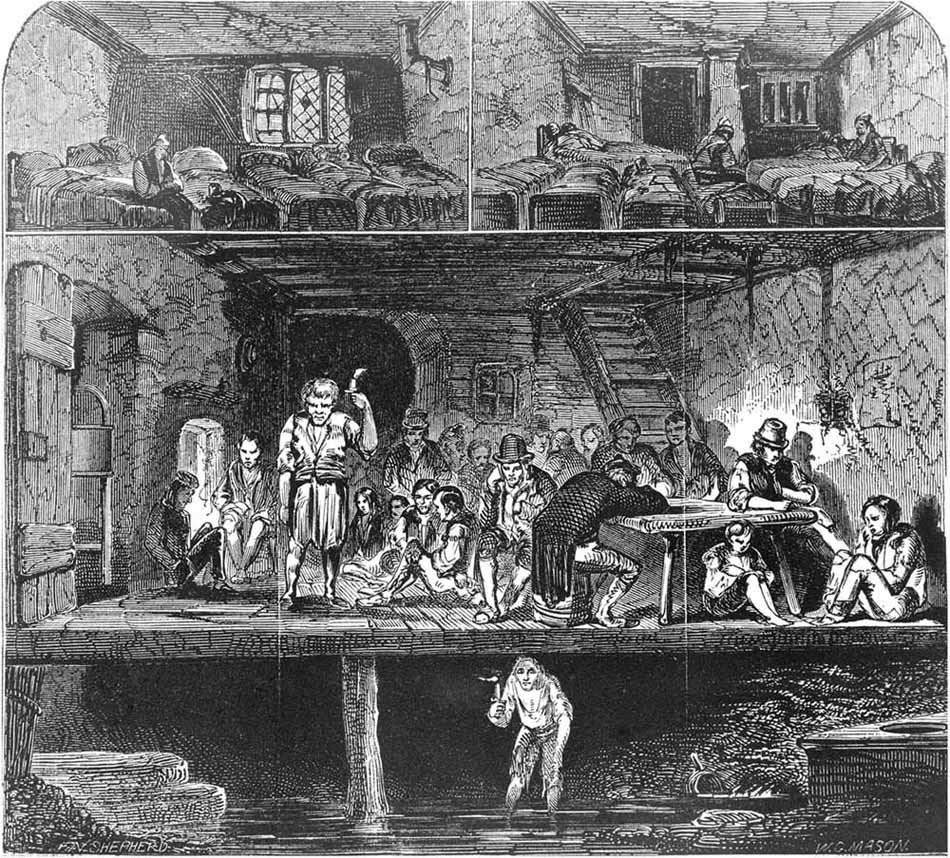

The devotion to fashion and/or fashionable ways of life, including things such as excessive dancing, or—on the opposite side of the spectrum—the lack of exercise, were all believed to cause tuberculosis. In the early part of the nineteenth century, for instance, as the waltz became popular, many physicians and social commentators claimed that its movements collaborated fatally with phthisis. In 1814, Hester Lynch Piozzi commented on the choices of one young lady on the occasion of the White’s Ball:14 “Miss Lyddel had the Offer of a Ticket but refused, because she was not half well: Dr. Baillie15 praised her, and said that 50 Girls more Ill than She—would go at all hazards, and that he expected 40 of them would die in Consequence of such Ardour after Amusement.16 The Manual for Invalids (1829) called dancing a “seductive amusement” that was “very liable to do harm” due to the violence and duration of the exertion. The author remarked, “Indeed, I have frequently known that the foundation of that most fatal malady, pulmonary consumption, has been very clearly traced to the returning home from the ball-room.17 This association between vigorous exertion and tuberculosis continued well into the nineteenth century. In 1845, The Medical Gazette made explicit the connection between dancing and consumption observing “the patient … had had repeated attacks of cough, pain in the chest and haemoptysis, the consequence of great exertion in dancing.18 Thus, the avoidance of illness and individual self-preservation rested increasingly upon the personal environment and individual behavior.

Figure 3.2 Death points an arrow at a female dancer. Aquatint by J. Gleadah, 18–. Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

In addition to clearly identifiable causes like environment and lifestyle, there were intangible, ephemeral causes of tuberculosis thought to be equally deadly to those hereditarily predisposed. Consumption seemed to attack the more vulnerable portions of the population with increased vigor, forcing an exploration of other contributing factors presumed to contribute to the illness, such as the mental and emotional. These ephemeral, emotional causes became increasingly central in the explanations of tuberculosis among the upper reaches of society.

The existence of an intimate connection between the mind, the individual, and his or her illness had been recognized since the ancient period, although the relationship had been couched in the terminology of the humors and their interaction with an individual’s psyche and soul. Piquant emotions like sadness or excessive joy were thought to trigger illness. By the eighteenth century, a more mechanical approach to the body had replaced humoralism, but the notion that disease was a product of disruption due to either physical, mental, or emotional stresses remained.19 The unity of function between the spirit and body did not lose its power with the acceptance of an anatomico-pathological approach to medicine. Instead, the focus on solidest thinking, which located disease in tangible bodily structures, particularly the nerves, was applied to the communication between the physical form and the soul. The actions of the solids and fluids replaced the humors, but the passions remained the manner in which the body and the soul met, interacted, and communicated.

Medical investigators sought to elucidate the particulars of the mind–body connection through an examination of the ability of the emotions and mental processes to disrupt health.20 Laennec was one of the many who tackled the part that an assortment of causes occasionnelles played in pulmonary consumption, categorizing the role psychosomatic factors, like the “sad passions,” played in tuberculosis and arguing for the destructive nature of deep, abiding, prolonged melancholy emotions.21 Hereditarians also fell back on the “sorrowful passions” in their explanations of disease; strengthening the idea that tuberculosis was an extension of the victim’s nature.22 Laennec maintained the sad passions accounted for the disease’s prevalence in the urban environment. For in the cities people were more involved in a variety of life pursuits, and with each other, and these circumstances provided a greater opportunity for disappointment, sadness, immoderate behavior, bad conduct, and bad morals, all of which could lead to bitter recrimination, regret, and consumption.23

Over the course of the eighteenth century, illness in general, and tuberculosis in particular, were increasingly linked to the functioning of the nervous system.24 Nerves were conceived of as having an innate sensibility, meaning a “nervous” person could develop consumption and waste away due to the quantity of his or her sensibility and the related psychological dynamics. Emerging models of the nervous system and the role of the “sensible body” were rapidly accepted later in the eighteenth century by a number of renowned physicians and philosophers who pushed for the dominance of the nervous system in the explanations of disease.25 (See Plate 12.) For example, Albrecht von Haller, the Swiss anatomist, undertook an extensive investigation of the workings of the nerves, arguing that the fibers of the nerves were imbued with an intrinsic property known as “sensibility.” For Haller, “sensibility” was the nerves’ ability to recognize and react to external stimuli. Tissues that were rich in nerves, including the muscles and skin, also possessed an increased degree of sensibility. Haller classified the “reactive” quality of both the nerves and the muscles, or their ability to respond to outside stimuli, as “irritability.” In 1752, Haller published the results of his experiments, which influenced the work of leading Scottish anatomists, like William Cullen, and helped force a key shift in medical theory.26

William Cullen’s work had a significant impact on the popularity of socio-psychological explanations of disease in England and was part of an extensive movement that pushed for the dominance of the nervous system in the explanations of disease.27 His work rested upon a patho-physiological approach to the mechanisms and processes of disease—which he believed were controlled by the nervous system. Cullen construed life as the consequence of nervous action, privileging the role of the nervous system in the creation of disease. He promoted the functioning of the nervous system as the source of life, and saw irritability and sensibility as a person’s most significant qualities. Cullen argued sensibility was the ability of the nervous system to not only accept sensations but also to convey the body’s will, while irritability was a type of “nervous power” located in the muscles. The degree of these qualities differed among individuals. Irritability, in fact, occurred in inverse proportion to an individual’s strength. For instance, a weak and debilitated individual would possess an elevated quantity of irritability, while a strong individual would possess less irritability and have a tendency toward torpor. Health was achieved through a balance between the sensibility of the nervous system and the irritability of the muscles. Should the equilibrium break down, creating a deficiency or excess of either of these qualities, disease was sure to ensue.28 Cullen extended these ideas, arguing that due to the primacy of the nervous system in the proper functioning of the body, all diseases had a nervous component. As a result, a neurosis was more than just a mental disease, it was any illness that resulted from an alteration in the functioning of the nervous system, particularly one that developed as the aftermath of emotion or sensation.29

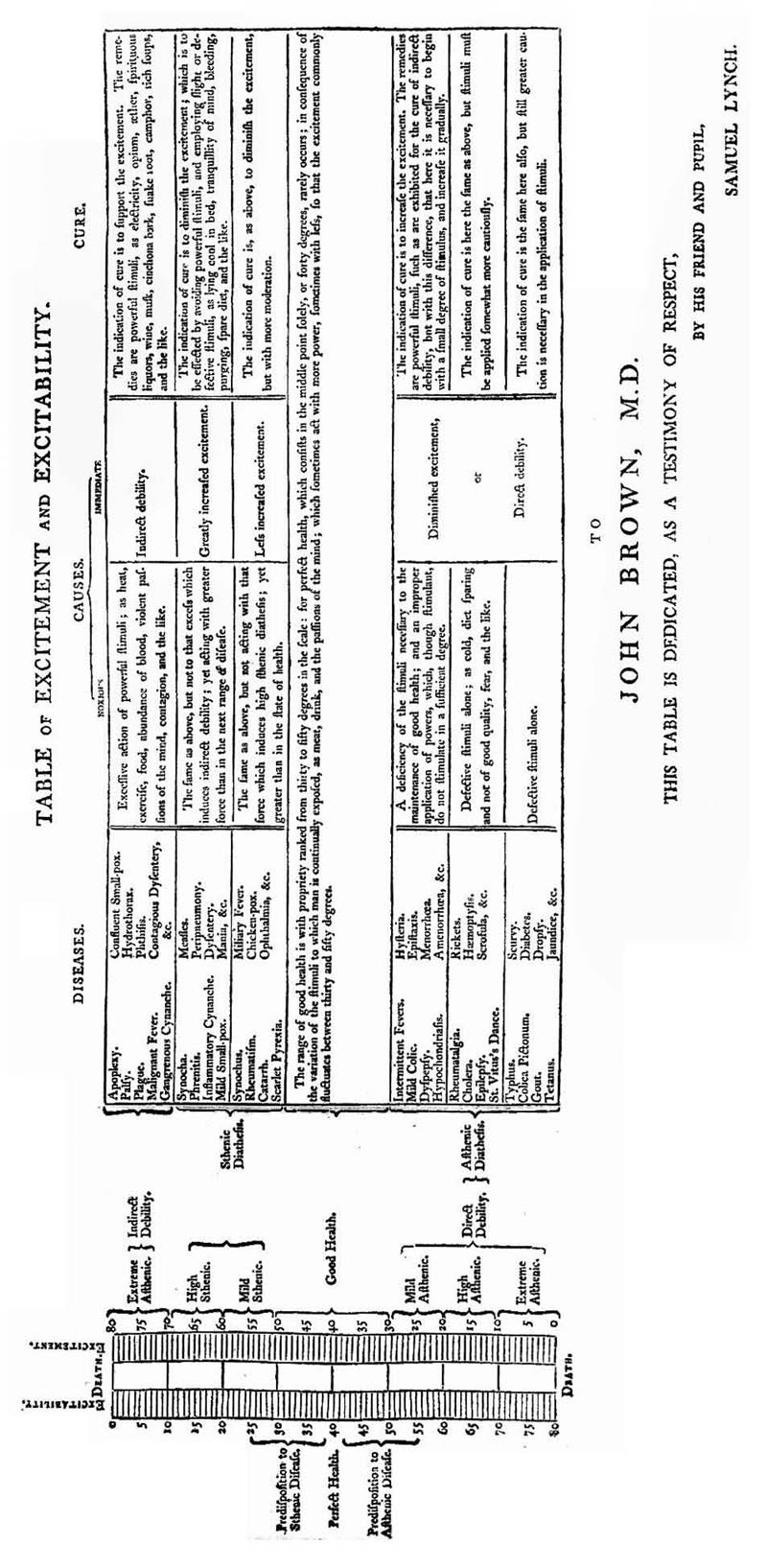

Cullen’s one-time student and later detractor John Brown (1735–1788) took the focus on neurophysiology in a different direction. Brown asserted that life rested upon “excitability,” and disease transpired when there was either a surfeit or a deficit of this property.30 For Brown then, illness was the outcome of a disruption in the performance of excitement, and the course of this disturbance determined the type of illness that developed.31 In his scheme, there were only two basic types of illness. An over excitement of the system produced a “sthenic” disease (like rheumatism, miliary fever, scarlet fever, and measles); while an insufficient quantity of excitement would lead to an “asthenic” disorder (like typhus, cholera, gout, dropsy, and phthisis).32

The majority of illnesses were thought to be asthenic in nature, the consequence of debility. Furthermore, an excess of excitement, characteristic of sthenic illness, could be exhausted, ultimately leading to asthenia, or an illness of “indirect debility.” The Brunonian system visualized sickness as the product of a general disruption of the patho-physiological processes and asserted that deviation from health was a quantitative and not a qualitative issue.33 The elevation of the nervous system had implications beyond the biological, as it was incorporated into the developing “cult of sensibility.” Sensibility involved a more refined type of suffering by those in the middle and upper classes and became one of the ways in which the middle class separated itself from the lower orders and constructed its own identity.34

Figure 3.3 John Brown by J. Donaldson after J. Thomson. Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

Sensibility was heavily embedded in eighteenth-century notions of the body, leading to new strategies of self-presentation and social performance, and sensibility signified the Enlightenment epistemology of the senses as the material origin of consciousness.35 The nervous system remained the foundation of this psycho-perceptual approach: the nerves transmitted sensations, and the speed of this transaction rested upon the elasticity of the nervous system. The suppleness of the nervous system was thought to be more highly refined among the middle and upper classes, a notion made even more fashionable by popular literature. Sensibility was even employed in the legal context as a defense strategy in some court cases.36 The adaptability of sensibility and its growing association with consciousness, emotions, knowledge, and refinement led to a continual redefinition of the term as well as its cultural and medical implications.37 From a medical perspective, cultural issues had biological consequences and there was a growing concern over the effect that this increasingly refined culture had in creating “nervous diseases.”

Figure 3.4 Table of Excitability. “Table of excitement and excitability … John Brown. (by) Samuel Lynch,” From The Elements of Medicine of John Brown, M.D. (London: J. Johnson, 1795). Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

The emergence of “civilized” diseases based on sensibility complemented the pervasive application of the action of the nervous system in explaining the incidence of certain illnesses.38 At the elite level, the elevation of the nervous system and the corresponding relationship between the mind and body led, according to Lawlor, “to a paradigm shift in which both medicine and literature were dominated by notions of nervous sensibility.39 Furthermore, Lawlor argues there was a parallel shift in the view of the body away from the notion of mechanistic clock or even the hydraulic machine, and instead toward the image of a string instrument, one that required the maintenance of proper tension in the nerves. Preservation of health could occur if the proper “elasticity” or “tone” in the nerves continued; otherwise, disease ensued.

Physicians expressed a growing concern over the effect that this increasingly refined culture, inhabited by persons of great sensibility, had in creating nervous diseases. The buffeting of the nervous system was creating a scourge of ill health among the upper and middle classes, due to their refined sensibilities and the pre-existing derangement of their nervous systems, which predisposed them to illness.40 In 1792, William White explicitly elevated the action of the nervous system in tuberculosis, arguing the predisposing causes included “A constitutionally weak system of blood-vessels; a too great irritability of the same” and a “Great sensibility of the nervous system,” as a consequence “it chiefly attacks young people; particularly those who are of active dispositions, and shew a capacity above their years.41

The idea of a disease of civilization, linked to the nervous system, rose to prominence during the eighteenth century, partly as a consequence of the social dislocation that occurred in conjunction with the explosion of commerce and urbanization.42 The rapid changes that accompanied progress seemed to be producing parallel pathological alterations. The harmful lifestyles associated with town living included overindulgence of food and alcohol, as well as lack of exercise and insufficient sleep. In addition, there were the pernicious effects of certain fashions, an excessive pursuit of luxury, the business of financial speculation, and the strict etiquette protocols of society in the metropolis. All of these practices created anxiety, depleted energy, and had a deleterious effect on an individual’s constitution. The artificiality of urban society was harmful to people on both a mental and physical level and led to the development of these new “civilized” sicknesses. The nervous system explained the observed physiological manifestations of these illnesses. The excesses of civilized society seemingly inhibited the proper communication between the brain and the rest of the body by blocking the action of the nervous fibers, leading to inflammation, pain, chronic feelings of exhaustion and lethargy, symptoms not observed in the sturdy and robust members of the lower orders.43 Indeed, the idea of a disease of civilization, linked to the nervous system, rose to prominence during the eighteenth century as the British nation gained a reputation across the continent as a hotbed of mental, nervous, and hysterical afflictions. The English came to believe that the price of their prosperity and refinement was sickness and pain, and asserted that the proliferation of “civilized” diseases were a mark of British superiority.44

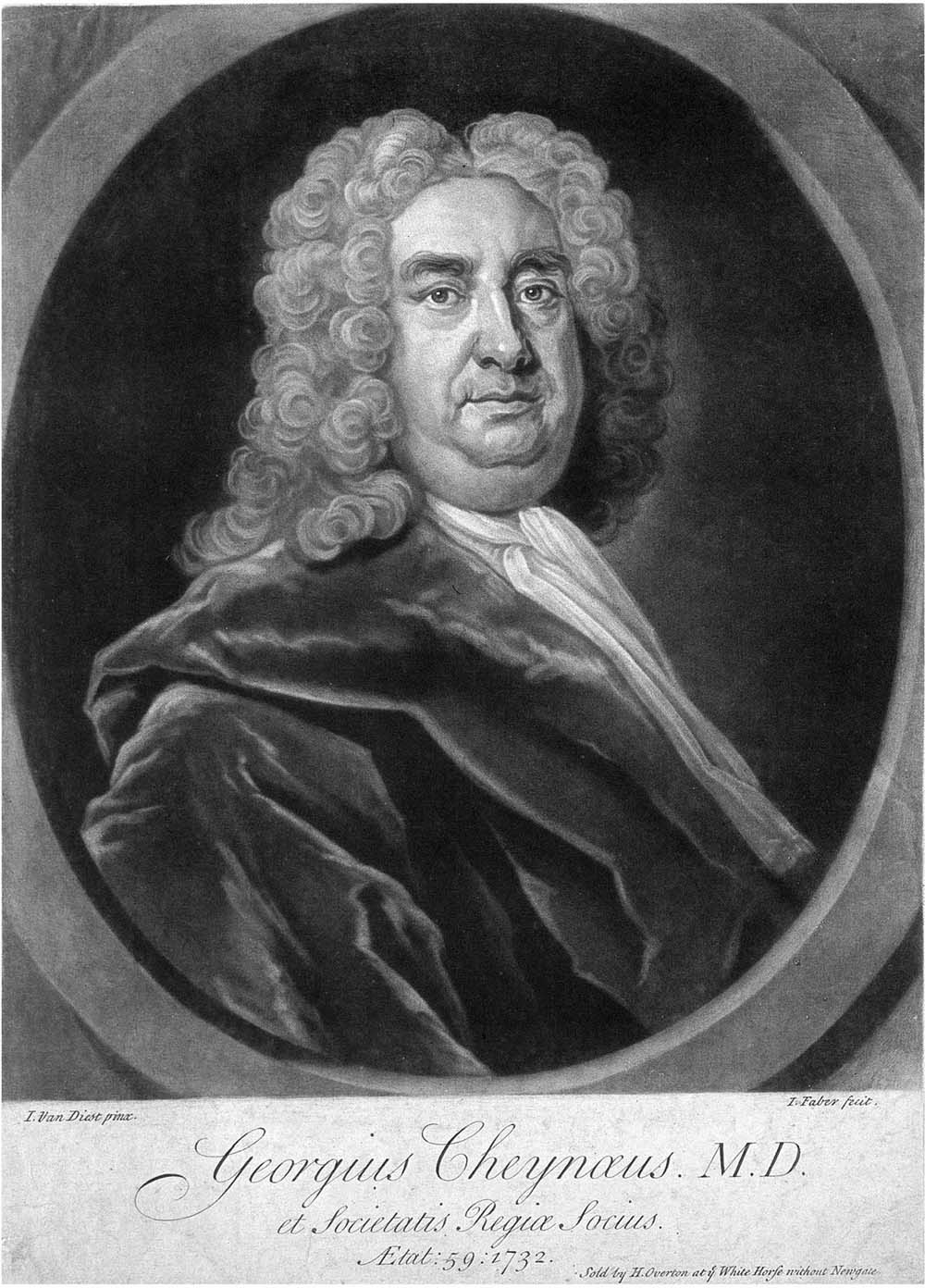

This line of thought was laid out early, in George Cheyne’s wildly successful The English Malady (1733). The work seemed to paint nervous illness with a new glamor and, by explicitly linking the lifestyles of the elite with conditions provoked by nervous debility, Cheyne implied that fashionability was partly contingent upon the effects of emotional and mental anxiety.45 His work provided a pathological model of the human body, one dependent on the actions of social factors, especially the “English way of life,” upon the nerves. In doing so, he evaded the more repulsive characteristics of disease, helping to make nervous disorders more socially acceptable.46 For Cheyne, the locus of disease rested in excess. To reach the pinnacle of society, denizens of the upper orders were often forced to surrender their health, physical fitness, and even their figure to the forces of fashion, business, or idle pleasures. Possessing, as they did, acutely reactive nervous systems, they were extremely vulnerable to a number of illnesses and were ensnared in a trap of their own making, in which social success perpetuated the suffering associated with illness.47 These “nervous disorders” were the product of civilization and indicated the social and economic accomplishments of the English.48 In this presentation, nervousness—and, by virtue of association, sickness—were both viewed as symptoms of success.49

Figure 3.5 George Cheyne. Mezzotint by J. Faber, junior, 1732, after J. van Diest. Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

Cheyne’s work on chronic illness was instrumental in the development of the philosophies that governed the perceptions of the interaction between an individual’s health and society. His work also helped to explain the oppositional relationship between wealth and health. Urbanization and its corresponding social consequences appeared to be increasing the vulnerability of the population, not just to diseases typically associated with filthy conditions, but also to neuro-pathological illnesses, like tuberculosis. For rich and poor, the city was dangerous to health, a fact widely acknowledged and often lamented. As one mother complained of her daughter,

I am afraid London does not agree with her, for she never is well there half a year together, this last illness was coming on before she left Town—’tis a grievous suspicion, now I have got such a charming home in Town!—I shall keep her in the Country ’till the end of Octr. & then try Town again—& if I find her ill there again, I fear I must endeavour to Let my dear Downing St. Home, & take a Country Cottage at once, for my Children & Governess—fond as I am of London, there seems a fatality against my living in it.50

Similarly, in 1832 Charles Thackrah argued, “Of the causes of disease, anxiety of mind is one of the most frequent and important. Civilization has changed our character of mind as well as of body. We live in a state of unnatural excitement;—unnatural, because it is partial, irregular, and excessive. Our muscles waste for want of action: our nervous system is worn out by excess of action. Vital energy is drawn from the operations for which nature designed it, and devoted to operations which nature never contemplated.51

The belief in a mind–body connection helped elevate the status of pulmonary consumption among the upper and middle classes. In the late eighteenth and well into the nineteenth century, the nervous constitution and its associated disorders were being presented in such a way as to make them attractive. Tuberculosis was now perceived as the physical manifestation of a psychological state and a symbol of an elevated aesthetic, physical sensitivity, as well as of a superior spirituality and intelligence. The specific mechanism of action was laid out by George Bodington in 1840 when he argued the first step in developing consumption “consists in nervous irritation, or altered action, or weakened power, in the substance of the lungs, from the presence of tuberculous matter deposited there as a foreign body.52 In the next phase, the nervous system manifested itself in pathological alterations in the tissues of the body.

So soon as the nervous power is entirely destroyed in those portions of the lungs where the tuberculous deposits exist, then the destruction of the remaining tissues follows immediately; they die, dissolve down into a half fluid half putrid condition, and are expectorated through the bronchial tubes, leaving cavities in the substance of the lungs … Here is then, first, nervous power altered, weakened, or exhausted; then the destruction of the remaining tissues, constituting the main substance of the organ.53

J. S. Campbell also wrote of the power of the nervous system and presented a rather attractive description of tuberculosis, writing even “slight causes of excitement, whether mental or corporeal, produce effects on the circulation which are not found in a body naturally robust.54 He described the physical manifestations of this excitement, stating in a person with a refined nervous system there were “sudden flushes of the countenance from trivial causes of mental emotion, which frequently suffuse the cheek of beauty with a blush originating in a fatal tendency, and hence the sudden but ill sustained fits of transient vigour, very foreign to the nature of the person who exhibits them. It is in constitutions presenting these peculiarities” that one found “a tendency to deposit tubercles.55 By twining consumption with the refinement of sensibility and presenting it as a product of high society, Campbell romanticized the disease. A person afflicted with such a condition had to be, by implication, fashionable, wealthy, gifted, intelligent, or inspired in some way. In this presentation, nervousness—and, by virtue of association, sickness—were both viewed as symptoms of success. The poor lacked both the material and the psycho-physiological endowment that would make them vulnerable to nervous complaints; as such, a separate dialogue developed to explain the incidence of illnesses such as tuberculosis among them.56 Diseases, then, were not just the affliction of fashionable people but were themselves becoming fashionable.

The connection between civilization, behavior, disappointment, and illness extended into a belief that a relationship existed between the physical environment, the social status, and the moral character of an individual. Dank, crowded, dark, poorly ventilated housing came to be seen as an environment favorable to fostering tuberculosis in the poor. However, the idea that consumption was a disease of the more refined elements of society informed an alternative narrative about the disease. The various ways in which tuberculosis was perceived, explained, understood, and rationalized provided the justification for opposing discourses of consumption as both a “social scourge” and a Romantic illness.57 There was a corresponding split in the explanations of tuberculosis by social status. Consumption was, in a number of senses, an archetypical illness of civilization. On the one hand, there was a connection between the disease and the unhealthy living conditions of the urban environment, such as smoke, dust, dirt, and damp. On the other hand, there was a strong tradition that associated the disease with the best and brightest members of society, those intelligent and delicate individuals who seemed so prominent in the ranks of its victims. There was an acceptance by physicians and society alike of an association between the illness and the sophisticated lifestyle pursued by members of the beau monde.58 The health of the individual now had wider implications as disease became a social problem, and those afflicted were provided a specific place within society—a position assigned not according to their approaching death but instead as a function of their unique quality of life.