Consumption, as an affliction from which neither class, wealth, nor virtue provided any protection, required rationalization in an effort to make the loss of loved ones more bearable. In their attempts to understand something as ambiguous as the social attitudes toward death in the nineteenth century, historians have proposed a variety of interpretations, in part revitalizing the notion of a good death based upon evangelical principles1 as well as promoting the idea of a culturally beautiful death.2 Philippe Ariès argued there was an influential cultural archetype in the notion of a “beautiful death,” one resulting from the transformation in the approach to illness and death that accompanied the Romantic Movement and presented death as a beautiful experience to be approached with enthusiasm rather than dread.3 Ironically, Ariès’ theory rests primarily upon the approach to death gleaned from the written remnants left by members of the Brontë family while they suffered from the ravages of consumption, again lending weight to the contemporary acceptance of tuberculosis as an easy and even beautiful ending. Patricia Jalland has argued that instead of a “beautiful death” there was a tendency once again toward a “good death,” now defined by the principles of evangelicalism.4 In fact, in the case of tuberculosis there was a reliance upon both, a search for a good and beautiful death—good in the approach to death and beautiful in the outward appearance imparted by the illness itself, as well as in the quality of the soul revealed by the afflicted’s handling of their decline and demise. Resignation to the Lord’s will, both by the sick individual and his or her loved ones, was an important component of a death from consumption.

Despite the medicalization of disease, tuberculosis remained intertwined with the conception of Divine will, as sin and redemption persisted as prominent features of a consumptive’s life and death. The prevailing approach rested upon the Christian ideology of atonement.5 Boyd Hilton has argued, “The sequence of sin, suffering, contrition, despair, comfort, and grace—shows that pain was regarded as an essential part of God’s order, and is bound up with the machinery of judgment and conversion.6 It is therefore not surprising that sickness, especially chronic illness, came to be characterized by an ideology of atonement, sacrifice, and the redemptive quality of suffering. The Christian sought to bear the burden of sickness well and in doing so, not only responded to the challenges of illnesses with dignity and strength but also gained a measure of control over the experience of sickness, if not over the outcome. This idea of “bearing up” became important, as did the related concept of “dying well.”

Minister Philip Doddridge’s personal experience with the tragedy of consumption offers a glimpse into the evangelical program for this disease. He provided a heart-rending account of his beloved daughter Betsy’s struggle with tuberculosis and death in 1736, just before her fifth birthday. Although Doddridge gave her a funeral sermon entitled Submission to Divine Providence, he clearly found this submission a difficult task, and in his diary admonished himself for his adoration of her.7 The power of this parent’s love was evident as was his struggle to accept her fate as God’s decision.

She was taken ill at Newport about the middle of June, and from thence to the day of her death she was my continual thought, and almost uninterrupted care. God only knows with what earnestness and importunity I prostrated myself before him to beg her life, which I would have been willing almost to have purchased with my own. When reduced to the lowest degree of languishment by a consumption, I could not forbear looking in upon her almost every hour. I saw her with the strongest mixture of anguish and delight; no chemist ever watched his crucible with greater care, when he expected the production of the philosopher’s stone, than I watched her in all the various turns of her distemper, which at last grew utterly hopeless, and then no language can express the agony into which it threw me.8

Doddridge went on to write of a curious event he attributed to his unwillingness to accept the Lord’s will and as punishment for his stubbornness, in this most personal of trials.

In praying most affectionately, perhaps too earnestly for her life, these words came into my mind with great power, “speak no more to me of this matter;” I was unwilling to take them, and went to the chamber to see my dear lamb, when instead of receiving me with her usual tenderness, she looked upon me with a stern air, and said with a very remarkable determination of voice, “I have no more to say to you,” and I think from that time, though she lived at least ten days, she seldom looked upon me with pleasure, or cared to suffer me to come near her. But that I might feel all the bitterness of the affliction, Providence so ordered it, that I came in when her sharpest agonies were upon her, and those words, “O dear, O dear, what shall I do?” rung in my ears for succeeding hours and days. But God delivered her; and she, without any violent pang in the article of her dissolution, quietly and sweetly fell asleep, as, I hope, in Jesus, about ten at night, I being then at Midwell. When I came home, my mind was under a dark cloud relating to her eternal state, but God was pleased graciously to remove it, and gave me comfortable hope, after having felt the most heart-rending sorrow.9

The importance of submission to the will of God and the Christian idea of death, continued as a significant feature of the approach to the consumptive death through the remainder of the eighteenth and well into the nineteenth century. In 1797, a letter on the death of yet another beloved from consumption shows its continued hold:

The account you give of her death is very affecting, but it is such as must give consolation to every man, who is not so unhappy as to relinquish the hopes of Religion. For my own part, I can honestly say that the more I see of the world the less I think we ought to regret those who are taken out of it, & when I consider the many disappointments & miseries, to which a maturer age is exposed, I cannot but regard the young, who are early called away, as “taken from the evil to come.10

The conviction that better things awaited the consumptive in the afterlife, based on the assurance of salvation in the evangelical tradition, lent further weight to the importance of resignation and this acceptance was a central feature in the personal accounts of those consumptives who ascribed to evangelical principles.

Resignation continued as an essential facet of the nineteenth century approaches to the illness and was evident in the writings of the young (Margaret) Emily Shore (1819–1839) about her disease. Even before her diagnosis, she was aware of the possibility that her illness was consumption, and began to prepare for that eventuality.

I get stronger, but my cough gives way very slowly, and my pulse continues high and strong. There is certainly danger of my lungs becoming affected, but we trust that, if it please God, the sea will restore me to health and remove the possibility of consumption. I know, however, that I must prepare myself for the worst, and I am fully aware of papa’s and mama’s anxiety about me.11

Within a month, she once again brought up her concern while being examined by Dr. James Clark. “I had no small reason to apprehend the pulmonary disease had already begun. I prayed earnestly for submission to the Divine will, and that I might be prepared for death; I made up my mind that I was to be the victim of consumption.12 Clark returned the news that her lungs were not yet affected, but Emily’s writing illustrated her conflicted feelings over the limitations placed upon her by illness.

I feel now quite convinced that I must not exert my mind at all, compared at least with what I should like to do. I cannot read or write without a headache, and writing also gives me a pain in my chest, which I have not, indeed, been free from for some days. It is very painful to me deliberately to lay aside all my studies, and it seems to me that I shall some time hence look back with great regret on the year 1836, the seventeenth year of my life, thus apparently wasted, as far as study is concerned. Yet I ought not to entertain this feeling, for it is God’s will.13

A year later she lamented, “How appalling is the progress of time, and the approach of eternity!” and acknowledged, “To me, that eternity is perhaps not far distant.14 She then asked, “let me improve life to the utmost while it is yet mine, and if my span on earth must indeed be short, may it yet be long enough to fit me for an endless existence in the presence of my God.15 Emily traveled to Spain for her health in 1838, providing a striking account of her visit to the graveyard set up locally for the numerous victims of tuberculosis.16

It was with a melancholy feeling that I gazed round this silent cemetery, where so many early blossoms, nipped by a colder climate, were mouldering away; so many, who had come too late to recover, and either perished here far away from all their kindred, or faded under the eye of anxious friends, who had vainly hoped to see them revive again. I felt, too, as I looked at the crowded tombs, that my own might, not long hence be amongst them. “And here shall I be laid at last,” I thought. It is the first time any such idea has crossed my mind in any burial-ground.17

The acquiescence to the inevitability of death marked a transition from a way of living to a way of dying, and an acknowledgment of the presence of consumption often led to a process of self-examination as part of the preparation for death. In his diary, the physician Thomas Foster Barham discussed his wife’s fears over spiritual preparedness and the effect of consumption upon her personality. In 1836 he detailed her life and death after twenty years of marriage. Although, in the end, his Sarah passed of a fever rather than from tuberculosis, he addressed the effect of that disease upon her during their long relationship. She was particularly concerned “about her religious state: she occasionally complained that she felt her heart cold and dead, and that she wanted something to rouse her spiritual affections: she also at times lamented some little yielding to irritability of temper in domestic vexations.18 However Barham remarked, “They were indeed little and very transient, a little momentary cloud passing over the sunshine of her habitual serenity and kindness. Such as they were, I have now no doubt that they arose in fact from that state of organic disease which was making a sure though insidious progress.19 He praised his wife, stating there was “unquestionable evidence that she had given of sincere devotion to him in the steady and conscientious manner in which she had long endeavored to discharge the various duties of her station in life. I pointed out to her that evidence of this kind was more to be trusted than that of excited feelings. In this way, I often restored her tranquility, and happy devotional hours took their turn.20 As in Sarah Barham’s case, notions of preparedness and appropriate behavior, remained laden with moral and religious precepts.

The continued emphasis on the importance of bearing up in a Christian manner while suffering from consumption was even evident in medical accounts of the illness. In 1831 members of the College of Physicians investigated the actions of the diseased body upon the mental state, stating “We were particularly struck with the sketch which was given of the cheerfulness of mind often exhibited by the poor victim of pulmonary consumption.21 It then went on to address the manner in which a victim endured that illness.

Figure 4.1 Margaret Emily Shore after unknown artist, engraving (c.1838). NPG D11267 ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

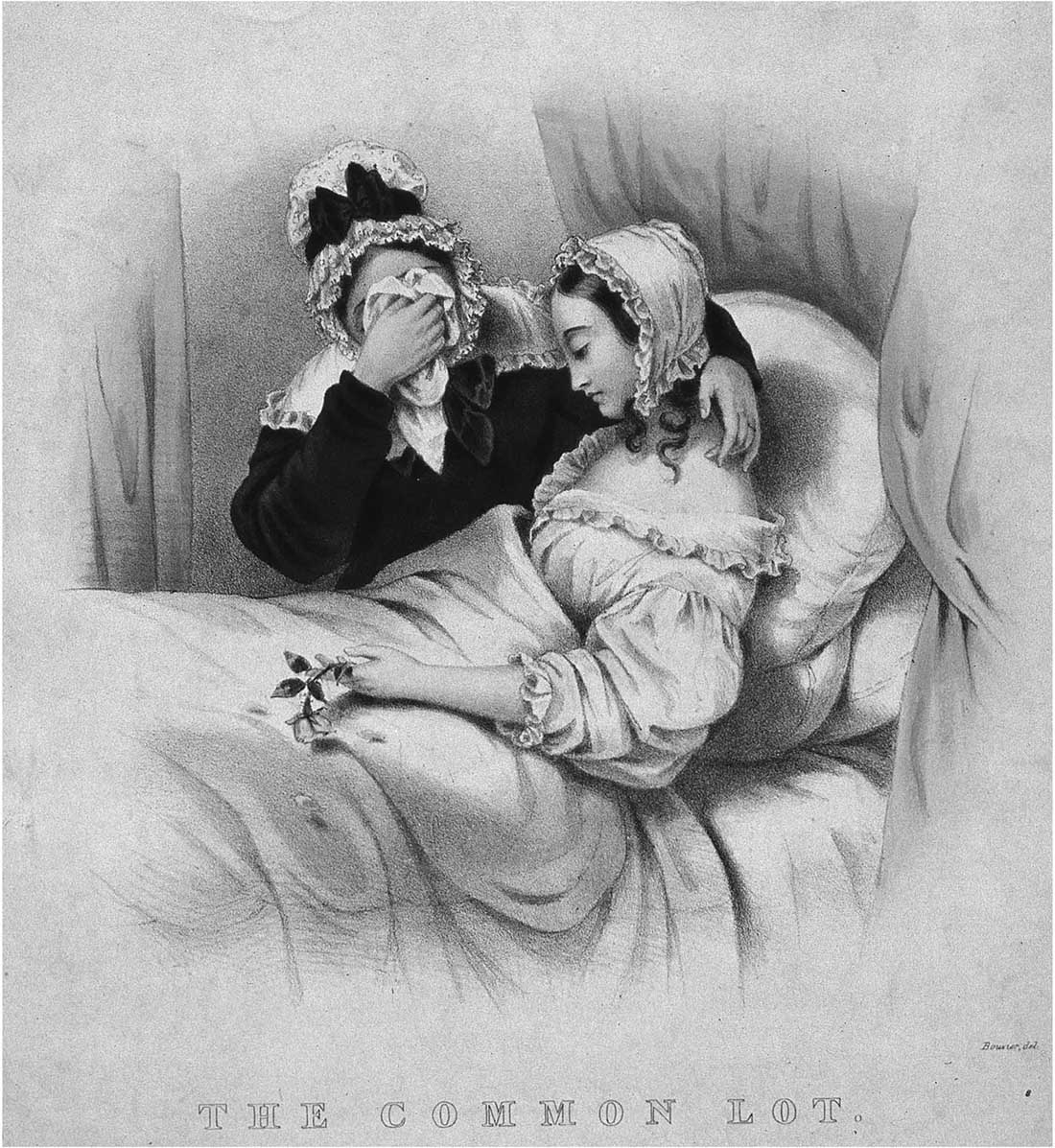

Figure 4.2 “Mourn Not your Daughter Fading.” A mother cries in grief while comforting her dying daughter. “The Common Lot,” colored lithograph by J. Bouvier. Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

But the Christian bears his sufferings from higher motives, and with a different spirit. It was mentioned by the president as a remarkable fact, that, of the great numbers whom it had been his painful professional duty to attend at the last period of their lives, very few have exhibited an unwillingness to die; except, indeed, from painful apprehensions respecting the condition of those whom they might leave behind. This feeling of resignation, although it might arise in some from mere bodily exhaustion, appeared in others to be the genuine result of Christian principles.22

God’s will would be re-employed by evangelicals and social reformers to fashion meaning and explain cause, by creating a vision of consumption that linked fate, personality, and inner truth to clarify both illness and death. Consumptives found comfort and meaning for their suffering in the belief that the disease was part of the Lord’s will. Additionally, in the homiletic of evangelicalism pain was assigned as central to God’s order, so it was a part of the apparatus of evangelical conversion and judgment.23 Suffering, illness and death were bound up with notions of providence and provided the opportunity to test the victim’s faith; as such, submission and resignation were the appropriate response.24 Yet people still struggled to understand the cause of their condition and why they, in particular, were afflicted. In the search for these explanations, lay understanding of disease causality bumped up against medical etiology, as the quest for meaning was marked by steady exchange between lay and learned opinion.25 This exchange was particularly important in elevating the influence of Romanticism in the rhetoric surrounding the illness.

Many have interpreted Romanticism, at least in part, as a reaction to the Enlightenment’s emphasis on rationality, because it elevated “moral passion” above intellectual scrutiny.26 This elevation of individualism and revival of emotion in literature, the arts, and the broader culture occurred in England roughly between 1780 and 1830.27 Romantics emphasized creativity, inspiration, and imagination, as well as the relationship between these forces and illness. Many even appeared to root literary intuitiveness in the disease process.28 Individual exceptionalism could not be had without a cost, and tuberculosis was an acceptable price to pay for extraordinary passion or brilliance. Illness was now an ally, not an enemy, and biological disease in the Romantic presentation became an intricate and treasured part of an individual’s personality.29

Sickness in general, and tuberculosis in particular, had a long association with mental exertion, a connection extended in the Romantic period to grant consumption the power of enhancing and freeing the creative sensibilities and imagination.30 The popularity of sensibility, and the reciprocal actions of the nervous system, implied to contemporaries that the stimulation of the mind had a dampening effect on the energy of the body. For the Romantic, the mind of the languid individual suffering from consumption was enhanced, and mental energy grew as physical torpor increased. When this energy was applied to artistic creativity, health was sacrificed in favor of imagination and ingenuity.31 The dominant culture of sensibility in the late eighteenth century cemented the notion of the body as the architect of knowledge and victim of its pursuit. The scholarly, artistic, isolated, and nervous body was both restricted and advantaged by inactivity. Suffering was co-opted by the artistic and scholarly into a self-affirming view of sickness, in which “learned” diseases like melancholia and consumption served as both the symptom and the source of literary achievement.32 Suffering, illness, and pain did not merely provide the opportunity to fulfill the prescribed evangelical deathbed ritual, but these experiences were also extended to serve as a source of artistic ingenuity, imagination, and intellectual prowess.33 “The Infirmities of Genius Illustrated” explicitly linked the constitution and literary creativity.

The “infirmities” of authors, their eccentricities of thought and action, their waywardness, peevishness, irascibility, misanthropy, murky passions, and the thousand indescribable idiosyncrasies, which, in all time, have contradistinguished them from their fellow-men, are proverbial. The anomalies thus so universally conspicuous in the literary character of men of genius … are referable to their constitutional (physical) peculiarities and condition: in simple words, that their mental eccentricities result from the derangement of bodily health. That the condition of the mind and the temper of man depends much upon the vicissitudes of health and disease of the corporeal frame.34

The Romantic emphasis upon exceptionality and individuality corresponded to a growing stress on the power of passion, love, sentiment, and grief. These notions applied to all aspects of life and death, romanticizing and beautifying the experience of both. Under these conditions death was sentimentalized and suffering, as well as death, were imbued with emotionalism.35 In the Romantic period, the wasting and emaciation of consumption added a fresh glamor to the artists and poets of the age. Thus, those illnesses thought to result from heightened sensibility were a double-edged sword. They brought the benefit of taste and refinement and elevated their sufferers socially; however, they also doomed their victims to an existence inundated by both mental and physical suffering.36 Poets were plagued with excessive irritability of their nervous system, which combined with their passionate natures to inundate their bodies with sensations that became pathogenic. The male poet’s consumption served not only as an expression of his sensibility, but also as a characteristic of his creative and intellectual distinction, as well as his inability to endure the harshness of the world.37

Consumption was the ally of the genius, who was consumed by his excessive emotional and intellectual activity, and exhausted his energy in a single burst that sped him toward death.38 This was not only a literary convention, but also one that found support in medical treatises, which defined genius as part of the constitutional construction of illness. For instance, in 1774 the Hibernian Magazine stated “The finest geniuses; the most delicate minds, have very frequently a correspondent delicacy of bodily constitution.39 While in 1792, William White listed among the predisposing causes to consumption a “great sensibility of the nervous system” which meant the disease “chiefly attacks young people; particularly those who are of active dispositions, and shew a capacity above their years.40 Clark Lawlor rightly calls attention to the contributions of Thomas Hayes and Thomas Young to this debate.41 Thomas Young’s A Practical and Historical Treatise on Consumptive Diseases (1815), argued, “Indeed there is some reason to conjecture, that the enthusiasm of genius, as well as of passion, and the delicate sensibility, which leads to a successful cultivation of the fine arts, have never been developed in greater perfection, than where the constitution has been decidedly marked by that character … which is often evidently observable in the victims of pulmonary consumption.42 Young was certainly not alone in making these connections, and A Physician’s Advice for the Prevention and Cure of Consumption furthered these assertions, stating: “It is a common remark too, that those thus unfortunately marked out as the victims of premature disease are, in the majority of cases, remarkable for their high flow of spirits, and for an unusual development of all those moral and intellectual qualities which dignify and adorn human nature.43

Tuberculosis and its accompanying symptoms were construed as the physical manifestation of an inner passion and drive. It was the outward sign of genius and fervor that literally lit the individual, providing the pallid cheek with a glow. The consumptive’s bright, shining eyes and pink, illuminated cheeks were seen as the outer reflection of the inner soul that was consuming itself, burning hot inside and out.44 In 1825 the European Magazine and London Review dedicated an article to the connection between intellect and illness, asserting:

It is a striking fact, that genius is often attended by quick decay and premature death … Genius when brought into material union, loves to dwell in the most spiritual form—the pale cheek, the dim eye, and the sickly frame. We seldom find that Promethean fire animating the coarse form of a ploughman. Besides, it heightens the preciousness of the gift when genius is bestowed only for a brief time, irradiating with intellectual light the young and untainted soul, and hurrying the possessor quickly away to an early tomb.45

Beyond the pathological alterations accompanying the destruction of the nervous power, there were also physical characteristics corresponding to the presence of a finer and more refined nervous system, ones evident in the consumptive individual. Those persons with a refined nature were thin and possessed a matching fineness and superiority in taste. In contrast, plumpness was associated with a lack of intellect, and the stout and portly were often described as tedious and slow.46 The notion that mental acuity was fixed in a lack of health continued to dominate the understanding of tuberculosis well into the nineteenth century. For example, in 1851 The Englishwoman’s Magazine and Christian Mother’s Miscellany stated, “Health, perfect and robust bodily health, is, perhaps, rarely found in combination with strong and fully developed intellect.47

Romantic symbolism took consumption beyond the simply physical, objective, progression of the disease and gave it an alternative meaning. The consumptive individual became the vehicle through which medical reality intertwined with popular ideology to craft the primary image of the sick individual.48 Thus, a benevolent view of the disease came to outweigh the far more frightening and disgusting reality of the illness. Clark Lawlor argues “that literary works combined with others (such as visual, religious, and medical) to produce cultural templates for consumption, and that writers provided the way for various groups of people to structure their experience of the disease, whether they be religious, poetic, male or female.49 The direct relationship between consumption and creative genius was not simply the product of conscious self-fashioning but was part of a wider cultural discourse. The mythology of the consumptive poet was given further impetus by the rise of literary criticism, which, by publicizing the poets themselves, in turn increased the visibility of consumption. 50

The most famous British example of the Romantic consumptive poet was John Keats (1795–1821), who perished from tuberculosis at the age of twenty-six. He exemplified the Romantic ideology surrounding the disease, and is better remembered for the tragedy of his consumptive death than the progress of his life. In the posthumous treatments of Keats’s death, the poet was absolved from responsibility in bringing about his illness. Instead, he was presented as destined to die from tuberculosis, which helped to elevate his death above all the others in the Romantic canon.51 There was a sense of inevitability to Keats’s end, in the way in which his illness was treated both during his life and after his death. His consumption was articulated as a function of his personality, his circumstances, and his talent. Percy Bysshe Shelley, in a letter to Keats on July 27, 1820, made the association between the poet’s talent and his illness. “This consumption is a disease particularly fond of people who write such good verses as you have done, and with the assistance of an English winter it can often indulge its selection.52

Beyond the connections made by the poets themselves, the link between consumption and intellectual prowess was made explicitly in the mid-1820s in an article which stated “the power of lingering disease to elicit intellect is frequently exhibited strikingly in the development of the mental faculties in victims of consumption, who, when hale and vigorous, were far from being of an intellectual turn.53 The representations of Keats’s life and the attitudes of his contemporaries to his illness and death embody the distorted approach toward the illness characteristic of the Romantic period. They also illustrate the continued difficulties experienced by nineteenth-century medical practitioners in treating a disease they had very little concrete information about, a circumstance that complicated the identification of the illness and its management.

Keats would have been rather knowledgeable about consumption, not only due to the personal tragedy of his family members and later himself, but also as a result of his medical schooling. Keats was a trained apothecary-surgeon and had received instruction at Guy’s Hospital (1815–1816) in London while apprenticed to Thomas Hammond. He also studied with Astely Cooper, who was widely held to be the best surgeon in England at the time.54 The contemporary presentation of Keats as possessing overly delicate sensibilities falters in the face of his enjoyment of, and attendance at, bear-baiting and boxing matches, as well as his forays into brawling which included a win over a butcher’s boy at the expense of a black eye.55

Keats’s story was one repeated in any number of households in England during the course of the nineteenth century, as his family was struck repeatedly by sickness. His uncle and mother both perished from “decline,” which could very well have been consumption, and his brother Tom also suffered from the disease.56 (See Plates 13 and 14.) Keats himself first took ill after a walking trip in the Lake Country and Scotland with Charles Armitage Brown. The strenuous exercise and inadequate food, coupled with a streak of bad weather, probably contributed to the sore throat and cold that Keats contracted, forcing his precipitous return to England via ship.57 Once home, Keats discovered that Tom was very ill and set about personally caring for him as he lay bedridden throughout the rainy winter of 1818. Despite Keats’s best efforts, Tom lost his battle with tuberculosis at the age of nineteen. On December 18, 1818, Keats wrote to his siblings to inform them of Tom’s demise. In his letter, he reflected on the final moments of Tom’s life and the meaning of his death. “The last days of poor Tom were of the most distressing nature; but his last moments were not so painful, and his very last was without a pang. I will not enter into any parsonic comments on death—yet the common observations of the commonest people on death are as true as their proverbs. I have scarce a doubt of immortality of some nature or other—neither had Tom.58 Keats further elaborated on the poignancy of lost youth and consumption in his in Ode to a Nightingale in 1819: “Youth grows pale, and spectre thin, and dies.59 The work was most likely an attempt to make sense of the tragedy not only of his brother’s illness but also of his own, which by then was already evident.60

By 1820, Keats’s health was failing and his narrative of his own illness presented the poet as being cognizant of the relationship between his physical and mental states. He consciously constructed a self-image of an individual marked both physically and psychologically by a nervous illness.61 He acknowledged the role of his temperament in the progression of his malady in a July letter to Fanny Keats. “My constitution has suffered very much for two or three years past, so as to be scarcely able to make head against illness, which the natural activity and impatience of my mind renders more dangerous.62 For the next several months Keats was plagued by recurring hemoptysis, so he decided to follow the advice of his physician and possibly gain relief from his affliction in the sunny climes of Italy. In September 1820, in the company of his friend Joseph Severn, Keats left for Italy where he sought the counsel of Dr. James Clark, the eminent physician of the English colony in Rome. Clark explicitly referenced Keats’s mental exertions in bringing upon his illness and initially believed allaying his mental turmoil would bring a return of health, writing on November 27, 1820: “His mental exertions and application have I think been the sources of his complaints. If I can put his mind at ease I think he will do well.63

During the winter, Keats’s condition worsened and Severn provided a graphic and disturbing account of Keats’s suffering in a letter to Charles Armitage Brown on December 17, 1820.

I had seen him wake on the morning of his attack, and to all appearance he was going on merrily and had unusually good spirits—when in an instant a Cough seized upon him, and he vomited near two Cup-fuls of blood … This is the 9th day, and no changes for the better—five times the blood has come up in coughing, in large quantities generally in the morning—and nearly the whole time his saliva has been mixed with it—but this is the lesser evil when compared with his Stomach—not a single thing will digest—the torture he suffers all and every night—and best part of the day—is dreadful in the extreme—the distended stomach keeps him in perpetual hunger or craving—and this is augmented by the little nourishment he takes to keep down the blood—Then his mind is worse than all—despair in every shape—his imagination and memory present every image in horror, so strong that morning and night that I tremble for his Intellect.64

Severn’s distress is clear and although Clark’s letters were more dispassionate, they expressed similar concerns over the patient’s mental state, writing on January 3, 1821:

He is now in a most deplorable state. His stomach is ruined and the state of his mind is the worst possible for one in his condition, and will undoubtedly hurry on an event that I fear is not far distant and even in the best frame of mind would not probably be long protracted. His digestive organs are sadly deranged and his lungs are also diseased. Either of these would be a great evil, but to have both under the state of mind which he unfortunately is in must soon kill him. I fear he has long been governed by his imagination and feelings and now has little power and less inclination to endeavour to keep them under … It is most distressing to see a mind like his (what might have been) in the deplorable state in which it is … When I first saw him I thought something might be done, but now fear the prospect is a hopeless one.65

Keats finally succumbed on February 23, 1821, and an autopsy revealed the extent of damage to his lungs.

Severn’s realistic and gruesome description of Keats’s final days does not fit with the eulogistic imagery presented after the poet’s death. Most of his contemporaries seemed to agree that disappointment and shattered hopes caused Keats’s consumption, but the source of that disillusionment was much debated. Keats’s friends, Severn among them, laid the responsibility for his illness on the poet’s state of mind. Although the criticism in the Quarterly Review was acknowledged, it was Keats’s love for Fanny Brawne that was accorded a larger role in creating the mental turmoil that led to his consumption. Both the poet’s friends and his critics disputed the role the unfavorable review actually played in Keats’s illness and death.66

The image of Keats provided by his contemporaries illustrates the power of the Romantic ideology in assessing this illness. Rather than identifying him as an individual who had a great deal of exposure to the disease through his family, he was presented as a delicate person whose sensitivity and weak constitution inevitably succumbed to consumption because he was unable to bear the buffeting of the unrefined wider world.67 Keats was increasingly represented as having been brought low by an unfavorable critique of his poetry in the Quarterly Review, and it was this image of the poet that seemed to be universally accepted even by his detractors. Lord Byron wrote the following to his publisher on hearing of Keats’s death:

You know very well that I did not approve of Keats’s poetry … [but] I do not envy the man who wrote the article; —you Review people have no more right to kill than any other footpads. However, he who would die of an article in a Review would probably have died of something else equally trivial. The same thing nearly happened to Kirke White, who died afterwards of a consumption.68

Byron’s allusion to the fate of Henry Kirke White was not the first such pairing with Keats; even before his illness, in 1818 his friend John Hamilton Reynolds had coupled the two in an article.69 In the work Reynolds lambasted the critics’ treatment of Keats, admonishing them to remember their effect upon Kirke White.

The Monthly Reviewers, it will be remembered, endeavoured, some few years back, to crush the rising heart of Kirk[e] White; and indeed they in part generated the melancholy which ultimately destroyed him; but the world saw the cruelty, and, with one voice, hailed the genius which malignity would have repressed, and lifted it to fame. Reviewers are creatures “that stab men in the dark:”—young and enthusiastic spirits are their dearest prey.70

The idea that Keats’s bout with consumption was precipitated by a brutal attack against his poetry motivated Shelley to style him as Adonais. In the introduction to Adonais, Shelley wrote:

The genius of the lamented person to whose memory I have dedicated these unworthy verses, was not less delicate and fragile than it was beautiful; and where cankerworms abound, what wonder, if its young flower was blighted in the bud? The savage criticism on his Endymion, which appeared in the Quarterly Review, produced the most violent effect on his susceptible mind; the agitation thus originated ended in the rupture of a blood-vessel in the lungs; a rapid consumption ensued, and the succeeding acknowledgments from the more candid critics, of the true greatness of his powers, were ineffectual to heal the wound thus wantonly afflicted.71

Shelley added to the Romantic mythology surrounding consumptive death with his homage to Keats in Adonais, in which he lionized the idea of a youthful demise:

Peace, peace! He is not dead, he doth not sleep—

He hath awakened from the dream of life—

…

From the contagion of the world’s slow stain

He is secure, and now can never mourn

A heart grown cold, a head grown grey in vain;

Nor, when the spirit’s self has ceased to burn,

With sparkless ashes load an unlamented urn.72

Shelley’s description of Keats’s death speaks to the beauty rather than horror of Keats’s end, “Ah even in death he is beautiful, beautiful in death, as one that hath fallen on sleep.73 This rendition in no way compares with Severn’s first-hand account, but it was Shelley’s image that triumphed. In his preface to Adonais, Shelley waxed lyrical upon Keats’s tomb, “in the romantic and lonely cemetery of the Protestants in that city … The cemetery is an open space among the ruins covered in winter with violets and daisies. It might make one in love with death, to think that one should be buried in so sweet a place.74 Shelley would join his friend in that place that made “one in love with death,” himself suffering from tuberculosis, though he was spared the consumptive death when he drowned sailing his yacht, the Ariel, off the Italian coast.

Keats exemplifies the Romantic ideology surrounding consumptive death in the first part of the nineteenth century; and although the ideology would remain pervasive, the tubercular disease process would increasingly become feminized. Though there would be alterations in the imagery and application of the mythology of consumption, there remained continuity in the notion that the disease provided a serene death. These ideas were still evident in the mid-nineteenth century when Florence Nightingale’s Notes on Nursing (1859) stated, “Patients who die of consumption very frequently die in a state of seraphic joy and peace; the countenance almost expresses rapture. Patients who die of cholera, peritonitis, &c., on the contrary often die in a state approaching despair. The countenance expresses horror.75 Representations of consumption, furnished compelling imagery for the individual and the social body that was extended during the nineteenth century to encompass notions of physical beauty and moral inspiration, particularly for tuberculosis in women.