Already established as an illness of thwarted love, diseased creativity, refinement, and nervous sensibility by the end of the eighteenth century, tuberculosis was increasingly intertwined with ideas of female attractiveness. This association was made possible by the discourse of sensibility that privileged delicacy and was supported by contemporary medical theory that supposed women’s nervous systems to be more fragile than those of men. Women were, biologically speaking, starting at a disadvantage. This situation was further complicated by their ever more ornamental and sedentary social roles, which seemed to create the perfect conditions under which consumption might flourish. Thus physicians, authors, and lay individuals alike participated in the identification of tuberculosis with beauty, refinement, and nervous sensibility. Consumptive mythology was powerful, and increasingly an aestheticized metaphor dominated the presentations of the illness.

Consumption was articulated as an illness that was not only beautiful in the physical and spiritual sense, but also as a disease that was associated with love. These notions had relevance in the individual constructions of the disease experience by both the victim of tuberculosis and those witnessing the inexorable progress of the illness. Susan Sontag argued that “many of the literary and erotic attitudes known as ‘romantic agony’ derive from tuberculosis … Agony became romantic in a stylized account of the disease’s preliminary symptoms and the actual agony was simply suppressed.1 By the latter part of the eighteenth century, individuals were using specific rhetorical imagery to fashion their experiences with consumption. Some elements of this mythology included a reinterpretation of the Christian “good death,” which embraced older ideas about consumption as a peaceful exit. In the sentimental incarnation, this gentle death was embellished with notions of beauty and of a young lady victimized by disappointment, particularly in love. In the case of women, descriptions of the causes of consumption and of the death from the illness often included the elevation of both spiritual and physical beauty.

Sarah Kemble Siddons (1755–1831), the most celebrated tragic actress of the eighteenth century, reached the height of her popularity during the latter part of that century.2 (See Plate 16.) At the same time that she was receiving critical acclaim, she was also facing financial and personal hardship, in part due to Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s poor management of the Drury Lane Theatre.3 Sheridan was constantly in arrears on Mrs. Siddons’ salary, and this fiscal instability may have been the motivating force to continue a precedent begun in the summer of 1784. Throughout the late 1780s and 1790s, at the end of the London theater season, Mrs. Siddons set about on a tour of Scotland and the north of England.4 Whether she actually required the money to supplement the funds Sheridan had failed to pay her or was simply lured by the lucrative profits from these summer tours is unclear. In 1798 however, Mrs. Siddons complained, while absent from her daughter Maria during that daughter’s illness, “My grief is that this whim of Maria’s [Maria’s desire to go to Clifton] separates us for I must wander about to pick up a little money to defray our expenses. I shall be with them about a month and then much away to play at Worcester Glouster [sic] Cheltenham by the Autumn I hope Maria will have had enough of Clifton and that we may be all together at Brighton where I shall play a few nights.5

What is clear is that Mrs. Siddons and her brother, John Kemble, had finally reached the end of their patience with Sheridan and at the end of the 1801–1802 season broke ties with the Drury Lane Theatre. Shortly afterwards, beginning in May of 1802, Mrs. Siddons would again leave her family and travel abroad on a performance circuit for more than a year in Ireland. During this excursion, it was Mrs. Siddons elder daughter, Sally, that was too ill to accompany her. Instead, she was attended by the daughter of Tate Wilkinson, the theater manager in York. Martha (Patty) Wilkinson had initially come to the Siddons home as a companion for the eldest Siddons daughter in 1799. She would accompany Mrs. Siddons on her Irish tour of 1802–1803, and indeed would remain her companion until Mrs. Siddons’ death.6 Whatever Mrs. Siddons’ motivations, her work accounted for her absences during key points in the illnesses of her two daughters. Mrs. Siddons’s busy schedule has permitted unique access to the progress and impact of the illnesses of her daughters, as experienced by her, and chronicled through letters with friends during long absences. Beyond providing a window into the disease process of consumption and its growing association with female ideals, the various theories and treatments of the disease are also apparent. Especially compelling was the part thought to be played by the love triangle involving both girls and the portrait painter Sir Thomas Lawrence. The unhappy consequence was taken by some to be the development, or escalation, of a consumption and the eventual death of the younger daughter.

In 1834 Charles Greville wrote in his memoirs:

Mrs. Arkwright told me the curious story of Sir Thomas Lawrence’s engagements with her two cousins … They were two sisters, one tall and very handsome, the other little, without remarkable beauty, but very clever and agreeable. He fell in love with the first, and they were engaged to be married … after some time the superior intelligence of the clever sister changed the current of his passion, and she supplanted the handsome one in the affection of the artist. They concealed the double treachery, but one day a note which was intended for his new love fell into the hands of the old love, who, never doubting it was for herself, opened it, and discovered the fatal truth. From that time she drooped, sickened, and shortly after died.7

As one might expect, the actual course of these romantic entanglements played out a bit differently than in Mrs. Arkwright’s accounting. Yet even in contemporary renderings of the affairs between Lawrence and the Siddons daughters, beauty remained a central theme. This focus on attractiveness was especially important to contemporaries as it accounted, in part, for the consumption that caused the “handsome” sister, to droop, sicken, and die. In courting them, Lawrence in fact, first traded in the “clever” and “agreeable” sister, Sarah Martha (1775–1803), affectionately known as Sally, for her younger sister Maria (1779–1798), the one displaying “beauty,” before once again swapping his affections as the more attractive Maria lay dying from consumption—hardly a noble portrait of the painter.

Both daughters were thought to resemble their mother in their good looks, although Maria was generally believed to be the more attractive of the two. References to the beauty of Maria began at a young age, as did her mother’s concern over the consequences of such loveliness. When Maria was only thirteen, Mrs. Siddons wrote to her friend Mrs. Barrington, “Maria is vastly handsome, I can scarce wish any daughter of mine to be remarkable for beauty, I need not prose to you the reason why.8 The reason was that beauty was believed to be one of the significant signs of a hereditary predisposition to consumption; moreover, once established, the symptoms were also thought to increase the attractiveness of the sufferer.

Sally, despite Mrs. Arkwright’s less than flattering account of her physical charms, was also recognized by her contemporaries as attractive—although, the representations of the elder daughter tended to focus upon her intelligence and character, particularly after her death. For example, the poet Thomas Campbell9 wrote upon seeing a bust of Sally Siddons that “She was not strictly beautiful, but her countenance was like her mother’s, with brilliant eyes, and a remarkable mixture of frankness and sweetness in her physiognomy.10 Both girls exhibited a certain delicacy of constitution, although Maria, with her greater beauty, was thought to have inherited the full measure of that delicacy.

Paradoxically, Sally was the first to demonstrate a susceptibility to respiratory illness when she was only seventeen. The indications of Sally’s tendency to infirmity occur early in her mother’s correspondence, as she was “taken illish” in October of 1792.11 Even before this episode, Sally had been placed on a regimen of asses’ milk, an accredited remedy for consumption and other respiratory and emaciating ailments.12 She would suffer several acute attacks of illness before she was struck down by what would eventually be labeled spasmodic asthma. According to her traveling companion, Mrs. Hester Lynch Piozzi, this was a particularly brutal episode as Sally was “seized yesterday with such a paroxysm of asthma, cough, spasm, every thing, as you nor I ever saw her attack’d by.13 Under the care of Richard Greatheed, Sally improved yet again, and once recovered, there were no concerns expressed that she might suffer any long-term difficulties or have a constitutional predisposition to illness. Sally’s medical history seemed to make her the more likely candidate for consumption, as asthma was an accepted antecedent to the disease; however, Sally’s “strength” of constitution would be employed to explain her continual triumphs over the bouts of spasmodic asthma that would plague her throughout her short life.14 In the end, it was the lovely and more delicate Maria who would contract consumption first.

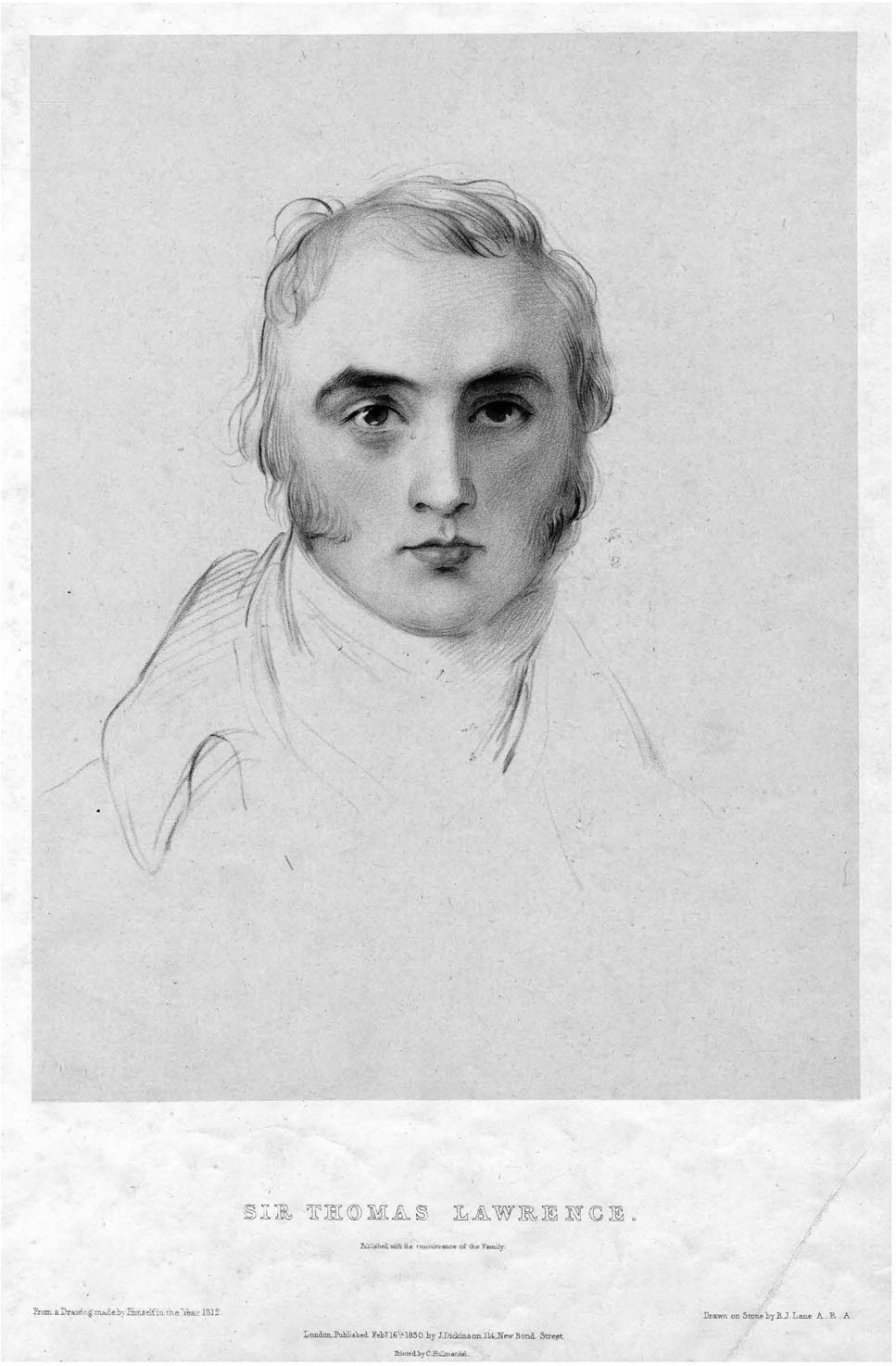

It is unclear at what point Thomas Lawrence entered the girls’ lives as an object of romantic interest. John Fyvie intimates that Lawrence must have met the girls not long after he established himself in London in 1787, as he quickly made friends with the Siddons family. At this point Maria would have been only eight years old and Sally around twelve.15 The girls’ acquaintance with Lawrence rekindled sometime in 1792 or 1793, when Lawrence then developed a tendre for the elder daughter Sally, who was at that time twenty.16 By end of 1795 or early in 1796, an understanding of romantic intent developed between Lawrence and Sally, (see Plate 17) one that evidently received the support of Mrs. Siddons, although she chose to keep the situation hidden from Mr. Siddons. Lawrence’s interest waned, however, and he rapidly transferred his affections to the younger, lovelier sister.

Despite her feelings, Sally seems to have graciously stepped aside in favor of her younger sister, and Lawrence formally proposed to Maria.17 The suit was refused by Mr. Siddons, both because of Maria’s youth, and Lawrence’s precarious financial position. Not willing to accept this decision, Maria sustained her relationship with Lawrence for close to two years through clandestine letters and meetings. A liaison made possible by a combination of assistance from Sally Bird and the complicity of Maria’s mother, who concealed the relationship to avoid her husband’s objections. Maria was permitted to meet with Lawrence with no other chaperone than the unmarried Miss Bird, hardly a likely choice as a companion to ensure respectability.18 The secret relationship between Lawrence and Maria continued until early in 1798, when Mr. Siddons finally agreed to the match.

What led to this change of heart? In the end, it seems that concern for Maria’s wellbeing played a large part in the decision. Maria’s health rapidly declined during the winter of 1797–1798. In January of 1798, Mrs. Siddons shared her concerns and fears that she may need to take Maria to Bristol for her health.

Dr. Pearson is decidedly of opinion that the Bristol waters are not proper for Maria at this time; and as any other air will be equally good in the present state of her complaint, and as going thither would be attended with great expense and inconvenience, we have given up that plan … The dreaded disorder, he says, has not taken place, but her lungs are in a state of susceptibility for receiving it that required unremitting attention for a great length of time.19

The relief over the verdict that Maria’s case had yet to progress to consumption was tempered by the looming threat of the disease striking at any time. In May, Mrs. Siddons expressed her continued apprehension over the possibility writing “Maria is still in a state of health which keeps me very anxious for the Consumption has not yet taken place. Yet I am given to understand that her lungs are in that susceptibility of receiving it, that all the vigilance of watchful tenderness may possibly be insufficient to elude its treacherous approach.20

The concern over Maria’s delicate constitution was an important deciding factor in the Siddonses’ agreement to allow their daughter to become engaged to Thomas Lawrence. A suggestion of their anxiety was evident in a letter of January 1798 from Sally to Miss Bird. “Maria determin’d to speak to my Father when she was much worse than she is now; she did, and now he, mov’d by the state in which she was … thought it most wise to agree to what was inevitable.21 Maria’s parents were concerned for their daughter’s emotional health, and therefore her connected physical state, as well as the possibility of an elopement if they continued to refuse to consent to the match. Once he had given in, Mr. Siddons even tackled the matter of Lawrence’s financial problems and made arrangements for his daughter’s future by settling the painter’s outstanding debts.22

Sally was optimistic this new turn of events would have a positive effect on Maria’s health despite Pearson’s gloomy pronouncements; reflecting the widespread belief that favorable circumstances, including a love affair that ended happily, had the power to forestall the onset of the tuberculosis in an individual constitutionally predisposed to the disease. Hence, she wrote to Mrs. Bird, “Should not this happy event have more effect than all the medicines? At least I cannot but think it will add greatly to their efficacy.23 For a short time, the decision to allow the engagement seemed to be the correct choice, as Maria’s health appeared to improve. On January 28, 1798 Sally remarked to Miss Bird, “I waited to send you news of Maria’s return to the Drawing Room, where she has now been for several days, and is recovering her strength and good looks every day. But here she must remain, Dr. Pierson [sic] says, during the cold weather, which means, I suppose, all the Winter.24

Sadly, Maria’s future was not as easily dealt with as her fiscal security, and her health once again precipitously declined beginning in February of 1798. Compounding her difficulties, within two months of her formal engagement to Lawrence, her fiancée seems to have transferred his affections back to Sally and embarked on a clandestine association with that sister.25 Sally, however, had not completely forgotten his earlier shabby treatment and inconstancy. The circumstances of their previous relationship still weighed heavily upon her mind. She was also concerned about the effect her renewed relationship might have on Maria, but convinced herself that her sister would not be severely affected because Maria’s feelings were not deeply engaged. At the same time, Sally preferred to keep her relationship quiet to prevent the possibility of upsetting her sister and addressed some of these concerns to Lawrence.

I wait but for the time when Maria shall be evidently engaged by some other object to declare to her my intentions, and then there will be no more of this cruel restraint and we may overcome the objections of those whose objections are of importance. You cannot be in earnest when you talk of being soon again in Marlborough Street; you know it is impossible. Neither you, nor Maria, nor I could bear it. DO you think that, tho’ she does not love you, she would feel no unpleasant sensations to see those attentions paid to another which once were hers? … Oh, no! banish this idea. Your absence indeed affects Maria but little—so little that I am convinced she never lov’d—but your presence, you must feel, would place us all in the most distressing situation imaginable.26

Figure 6.1 Portrait of Maria Siddons; after T. Lawrence (Garlick undescribed); illustration to “Library of the Fine Arts” (1831) Stipple. 1933, 1014.543 ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

Sally was obviously emotionally invested, as the mood of the letter turned downright giddy and demonstrated a schoolgirl fascination. She implored Thomas to pass by her parlor window at nine in the morning, as she was “generally writing or reading at that hour.27 Sally then went on to deal with the sticky situation of his fidelity and unreliability.

Need I tell you there is one (if he is but constant) whose company I would prefer to all the world? … I tell you now, before you proceed any further, that if I love you again I shall love more than ever, and in that case disappointment would be death.28

This notion that Sally could be disappointed to the point of death was not just an overwrought emotional exclamation, but reflected the well-established belief that disappointments, particularly in love, could lead to the development of consumption and consequently death.

As early as February of 1798, the temperamental Lawrence was once again exhibiting signs of irritability, depression, and restlessness. He finally confessed to Mrs. Siddons his renewed attachment to Sally and his engagement to Maria was officially terminated in March of 1798. The invalid seems to have dealt well with the romantic reversal of fortune and her lover’s abandonment.29 As Sally told Miss Bird,

Maria bears her disappointment as I would have her, in short, like a person whose heart could never have been deeply engag’d … It is now near a fortnight since this complete breaking off, and Maria is in good spirits, talks and thinks of dress, and company, and beauty, as usual. Is this not fortunate? Had she lov’d him, I think this event would almost have broken her heart; I rejoice that she did not.30

Sally and Lawrence’s association would remain clandestine however, as Mrs. Siddons once again decided to keep yet another relationship a secret from her husband. Despite her apparent acceptance of Sally and Lawrence’s renewed relationship at her expense, Maria did however, apportion blame for her illness to the experience and to her erstwhile suitor’s behavior. She wrote Miss Bird soon after Sally did, “he himself, if it is possible any feeling can remain in him, will acknowledge how little he deserv’d the sacrifices I was willing to make for him.31

Maria’s correspondence demonstrated far more concern about her health than her lover’s abandonment, and her disease increasingly became the primary focus of her life. On March 14, 1798, she recounted some details of her illness to Miss Bird, writing, “I feel a sad pain in my side.32 She went on to discuss the difficulty she was having in coping with the reality of her malady. “A relapse is always worse than the original illness, and I yet think I shall not live a long while, it is perhaps merely nerveous, but I sometimes feel as if I should not, and I see nothing very shocking in the idea; I can have no great fears, and I may be sav’d from much misery. I fear never creature was less calculated to bear it than I am, and in my short life I have known enough to be sick to death of it.33 The disease was proving a toll on Maria’s emotional, as well as her physical, health. She told Miss Bird, “I look forward with impatience to the time when I shall be myself again, and now I will endeavour to shake off this oppression, and entertain you a little better34 Maria’s correspondence also provides some insight into the lonely existence often experienced by the consumptive invalid, and a yearning for a return to normalcy.

I long so much to go out that I envy every poor little beggar running about in the open air. This confinement becomes insupportable to me, it seems to me that on these beautiful sun-shine days all nature is reviv’d, but not me: for it makes me regret the more that I may not enjoy the air, who have so much need of it to cheer me after such an illness … I expect to go to a very beautiful place this summer, Clifton, but I look forward to it with no pleasure; for the first time I shall be separated from Sally and my mother both, they go to Scotland, which will be too cold an air for me to venture in. I shall, I believe, be with a Lady at Clifton, where, if I can keep up my spirits, I am more likely to get well than in any other place in England.35

As her disease increasingly became the primary focus of her life, Maria’s beauty would gain a prominent place in representations of her illness. For instance, a family friend, Mrs. Piozzi, provided an outsider’s view of Maria at the time of her engagement’s end, writing that “Maria … looked (to me) as usual, yet everybody says she is ill, and in fact she was bled that very evening.36 This failure to recognize Maria’s illness was due, in part, to the difficultly of differentiating between the physical appearance of an individual with a hereditary predisposition to consumption and one experiencing an acute attack. The difference in appearance between predisposition and active illness was a matter of degree. In Maria’s case, her natural state was considered attractive, and as the disease progressed, the links between the illness and her beauty became more significant and were mentioned more frequently by family and friends.

Mrs. Piozzi’s assessment of Maria’s illness also demonstrated the difficulty physicians had in gaining acceptance for the anatomico-pathological approach to consumption. In the same letter, she complained about what she termed the “new fangled” approach to the disease and lamented the contemporary therapy. “Shutting a young half-consumptive girl up in one unchanged air for 3 or 4 months, would make any of them ill, and ill-humoured too, I should think. But ’tis the new way to make them breathe their own infected breath over and over again now, in defiance of old books, old experience, and good old common sense. Ah, my dear friend, there are many new ways,—and a dreadful place do they lead to.37 Her attitude reflected the continued acceptance of older humoral and miasmatic approaches to illness as well as traditional therapeutics, including bleeding and blistering, both of which were used on Maria in the spring of 1798.

As her illness progressed, Maria became increasingly frustrated and focused, in particular, on what she perceived as her failure to bear up appropriately under her affliction. She even expressed concern over the effect that her melancholy was having upon her loved ones. “It appears to me that I should be very like myself if I could but take a walk, and feel the wind blow on me again,” she wrote to Miss Bird. “I am indeed doubly unhappy, whenever I cannot keep up my spirits, to see I hurt my Mother and Sally. I am angry with myself though I am conscious of struggling against it.38 She then berated herself: “Have I not written you a stupid letter? Indeed, it is a great exertion. I hate writing lately, but I shall always be delighted to read your letters when you will send them to me, and perhaps some time I may be rous’d from this low, stupid way, and be able to entertain you better.39 Maria was concerned about her handling of her illness, particularly what she considered to be her unsuitable feelings in the face of her suffering. In response to her own evaluation, Maria made a concerted effort to modify her behavior, asserting “patience and resignation must be my virtues, and [tho’] they are severely try’d, the reward will, of course, be glorious.40

By May of 1798, Mrs. Siddons was very concerned over what she saw as the increasingly slim possibility of Maria’s recovery. “The illness of my second daughter has deranged all schemes of pleasure as well as profit,” she wrote to Tate Wilkinson. “I thank God she is better; but the nature of her constitution is such, that it will be long ere we can reasonably banish the fear of an approaching consumption.41 This letter marked Mrs. Siddons’s first real acknowledgment that her daughter had a constitutional predisposition to the illness. Mrs. Siddons also provided a glimpse of how heart wrenching it must have been for a mother to watch her beloved child slowly fade before her eyes: “It is dreadful to see an innocent, lovely young creature daily sinking under this distress, you can more easily imagine than I can describe.42

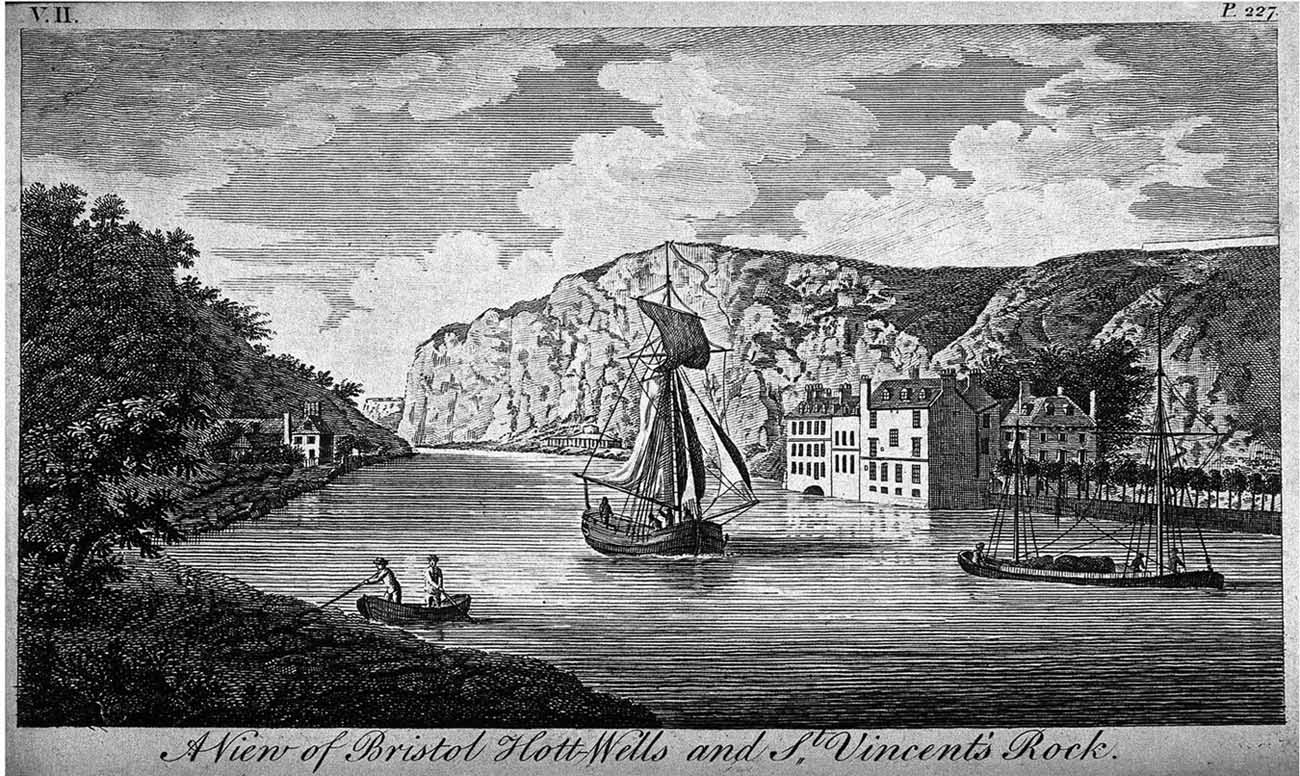

With the possibility of a cure slipping away, the family sent Maria to Clifton, which along with the nearby Bristol Hot-wells, was a well-known retreat for consumptives during this period. As a destination for the sick, the town was made more attractive by the social activities available to those seeking not only health but also an alleviation of the boredom often associated with invalidism. Located a mere fourteen miles from Bath and only two miles from Bristol itself, the Hot-wells were situated below the village of Clifton. Rather than detracting from its popularity, the proximity of the Hot-wells to Bath proved advantageous, as the waters at the two spas were believed complementary and serviced separate illnesses. Bath’s waters were touted as stimulant in nature and so beneficial to digestive complaints, while the waters of the Hot-wells were supposedly sedative and particularly beneficial in cases of inflammatory disease such as consumption. The status of the Hot-wells was enhanced by the timing of its season, which filled the space between the two popular seasons at Bath and provided an additional warm weather option, beyond the summer season at Tunbridge Wells. The popularity of Clifton was bolstered by the daily summer coach service running between Bristol and Bath that began in 1754, as well as affordable post-chaise journeys to the Hot-wells.43 The New Bath Guide (1799) stated, “The season for drinking the water is from March to September, when the place is much frequented by the nobility and gentry.44 William Nisbet’s, A General Dictionary of Chemistry (1805) provided slightly later dates, asserting that “from May to October is the favourite period of the season for the enjoyment of Bristol wells, but the mildness of the climate should always tempt to a longer residence, and on this account it should form the spot for the invalid to spend the winter, if obliged to pass it in Britain.45 Dr. William Saunders, in his treatise on mineral waters, confirmed Nisbet’s dates, maintaining that “the season for the Hot-wells is generally from the middle of May to October, but as the properties of the water are the same during the winter, the summer months are only selected on account of their benefits arising from the concomitant advantages of air and exercise, which may be enjoyed more completely in this season.46

By the mid-eighteenth century, the Hot-wells at Clifton was a fashionable resort frequented by the social elite. In 1789, Dr. Andrew Carrick described the place: “The Hot-wells during the summer was one of the best-frequented and most crowded watering-places in the kingdom. Scores of the first nobility were to be found there every season.47 In 1793, Julius Caesar Ibbeston pronounced the village of Clifton as “one of the most polite of any in the kingdom.48 He went on to enumerate the advantages of the Hot-wells: “The wells have the necessary attendant of such a place, gaiety. The resort to them is great, and during the summer months, a band of music attends every morning. Here is a master of ceremonies, who conducts the public balls and breakfasts, which are given twice a week.49 Dr. William Saunders called the resort “peculiarly calculated for the pleasure and comfort of the invalid.50 The Hot-wells water was reputed to be effective in cases of pulmonary consumption, either as a cure or as a palliative. Saunders stated that although the idea of a cure was unlikely, the Bristol water “alleviates some of the most harassing symptoms in this formidable disease.51 Robert Thomas’s The Modern Practice of Physic (1813) argued that the “benefit … should not be attributed wholly to the waters.52

Figure 6.2 Hot-well House and St. Vincent Rocks. Line engraving, early eighteenth century. Wellcome Library, London. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/

The horse exercise, which is taken daily by such patients, on a fine airy down … the salubrity of the air; the healthfulness of the situation, and the frequent attendance on the different amusements which are furnished at these wells, prove beyond all doubt the most powerful of auxiliaries. Places of public resort are food to the mind of convalescents, and serve to keep it in the same active state that exercise does the body, preventing thereby that indulgence in gloomy reflection, to which the want of cheerful scenes and agreeable company is apt to give rise in those who have an indifferent state of health … Nay, I am decidedly of the opinion that at least three-fourths of the cure attributed to all mineral waters, ought rather to be placed to the account of a difference in air, exercise, diet, amusement of the mind, and the regulations productive of greater temperance, than to any salutary, or efficacious properties in the waters themselves.53

A consumptive in The Lounger’s Common-Place Book (1799), however, offered a very different view of how to approach the disease and of Clifton.

I will try every resource which experience, judgment and qualified professors can point out; but once convinced that my disease is a consumption. I will fly from quackery as a pest, and from the apothecary as an unnecessary appendage; and not possessing a sufficient fortune to carry a ship load of friends with me to Lisbon, I would submit with all possible content to the circumstances of my situation, and moderately indulging in whatever food my stomach would take, pass the short remains of life in the bosom of my family. For death in any form, is far preferable to being dismissed to cough a man’s heart out in a solitary gravel pit, or to being exhausted by a journey to Clifton, with ghastly undertakers, thrusting their cards of funerals performed, into the post-chaise; apothecaries anticipating nitre powders, spermacaeti drafts, silk hat-bands, and long bills; and carpenter’s apprentices taking measure of a skeleton as he walks down the street, and wondering the gentleman remains so long.54

The Siddons family arrived in Clifton in the summer of 1798, according to Sally, due to Maria’s “strong desire to come here.55 Shortly thereafter, Mrs. Siddons embarked upon a tour of the Midlands with Sally, leaving Maria in the care of Mrs. Pennington, who resided in fashionable Dowry Square.56 Maria seems to have taken full advantage of all that Clifton and the Bristol Hot-wells had to offer, as she immediately began “to drink the Waters, and to ride double.57 While on tour Mrs. Siddons made numerous inquiries and comments concerning Maria’s health. On July 26, she wrote to Mrs. Pennington, “I know she went to a Ball, I hope it did her no harm. This weather has prevented her riding too; tell me about her pulse, her perspirations, her cough, everything!58 Her concern over the burden that Maria’s social activities were placing on the invalid was clear, as was her anxiety over the possibility of her daughter not being able to accomplish the prescribed horseback riding.59 Despite her unease, Mrs. Siddons remained hopeful that Clifton and the Bristol waters would prove beneficial to Maria’s constitution. The reports on Maria’s condition establish the picture of a young woman who, if not on the mend, was at least enjoying the entertainments available in Clifton.60 Thus Sally wrote Miss Bird on July 17, “Maria sends good accounts of herself, and has been allowed to go to two balls, tho’ not to dance.61 The belief that this activity was an exciting cause of consumption may have contributed to the decision that the frail girl would not be permitted to dance.

By the end of July 1798, Mrs. Siddons seems to have accepted the seriousness of her daughter’s illness, and her fears increased as Maria began to fade. She expressed her gratitude to her friend Mrs. Pennington for the solicitous care of her daughter, writing “The dear creature … says that she cou’d not have been so happy in any other situation absent from us as with you … How sadly unfavorable is the weather, but let me hope it is settled with you, and that she is able to take her rides!62 Mrs. Siddons’ letter also reflected the commonly held notion that the changes produced by the progress of consumption were attractive upon the face of its victim, as she wrote “of watching each change of her lovely, varying, interesting countenance.63

By August, Mrs. Siddons’s letters to Mrs. Pennington revealed her resignation to, and acceptance of, Maria’s fate. “Mine is the habitation of sickness and sorrow. My dear and kind friend, be assur’d I rely implicitly on your truth to me and tenderness to my Sweet Maria. I do not flatter myself that she will be long continued to me. The Will of God be done; but I hope, I hope she will not suffer much!64 She also addressed her fears for her elder daughter’s future, writing on the state of Sally’s constitution. She was clearly concerned that delicate health would affect Sally’s marriage prospects, despite Lawrence’s renewed affections.

How vainly did I flatter myself that this other dear creature had acquired the strength of constitution to throw off this cruel disorder! Instead of that, it returns with increasing velocity and violence. What a sad prospect is this for her in marriage? For I am now convinc’d it is constitutional, and will pursue her thro’ life! Will a husbands [sic] tenderness keep pace with and compensate for the loss of a mother’s, her unremitting cares and soothings? Will he not grow sick of these repeated attacks, and think it vastly inconvenient to have his domestic comforts, his pleasures, or his business interfered with by the necessary and habitual attentions which they will call for from himself and from his servants? Dr. Johnson says the man must be almost a prodigy of virtue who is not soon tir’d of an ailing wife … To say the truth, a sick wife must be a great misfortune.65

Like her mother, Maria was increasingly anxious not only about her own illness but also about Sally’s future. Maria was plagued by anxiety and depression, which increased as her body weakened, as did her apprehension over Sally and Lawrence’s love affair. Whether out of concern for Sally’s happiness or her own jealousy, she became convinced that the union must be prevented and no amount of pleading or cajoling on the part of Mrs. Pennington allayed her concerns. Mrs. Pennington quickly relayed the invalid’s deteriorating mental and physical state to her mother, who responded by sending Sally to Clifton. After her arrival, Sally related Maria’s condition to Miss Bird:

I found my poor dear Maria, much worse than when I left her; she was rejoic’d to see me, and my presence has so reviv’d her, she seems so happy to have me with her that I thank Heaven we so immediately determin’d upon my setting off for the Wells. Yet my dear friend, this is but momentary comfort, for it is but too evident we have but little hopes, alas! None, I fear, for the future. The Gentlemen who attend upon her assure us there is no immediate danger, and tell us of persons who have been much worse and yet have recover’d; but I am certain they have no hopes of Maria’s recovery, and I am prepared for the worst.66

To complicate the situation, Lawrence returned to center stage. Concerned that Sally might be denied to him, he rushed to Clifton to plead his case. In a letter to Mrs. Pennington that warned of his approach, Mrs. Siddons touches upon Lawrence’s possible guilt over his harmful effect on both her daughters and was especially troubled over how Lawrence’s presence and behavior might distress Maria.67 She wrote, “the effect on my poor Maria! Oh God! His mind is tortured, I suppose, with the idea of hastening her end. I REALLY, my dear friend, do not think so, and if one knew where he was, to endeavour to take this poison from it, he might be persuaded to be quiet. Dr. Pearson premis’d from the very beginning all that has or is likely to happen to her. But the agonies of this poor wretch, if he thinks otherwise, must be INSUPPORTABLE.68

Figure 6.3 Portrait of Thomas Lawrence, after a self-portrait (1812). 1838, 0425.185. Published 1830 by J. Dickinson. ©The Trustees of the British Museum.

In going to Clifton, Lawrence was intent on ensuring his relationship with Sally continued. In a letter to Mrs. Pennington pleading his case, Lawrence acknowledged the charges against him with respect to Maria’s consumption. “My name is Lawrence, and you then, I believe, know that I stand in the most afflicting situation possible! A man charg’d (I trust untruly in their lasting effect) with having inflicted pangs on one lovely Creature which, in their bitterest extent, he himself now suffers from her sister!69 However, he excused his actions and placed the blame for Maria’s ill health upon the invalid and her constitution.

Miss Maria’s situation is, I know, a very dangerous one. If it is REALLY render’d more so by feelings I may have excited, the least mention of me would be hazardous in the extreme. If it is not, and her complainings on this head are but the weakness of sick fancy, perhaps of Hope, wishing to attribute her illness to any other than the true fix’d CONSTITUTION and alarming cause, still it will be giving an additional distress to her Sister, and afford another opportunity for wounding me with a real, THO’ NOT INTENTIONAL, Injustice.70

Mrs. Pennington, agreed to meet with the artist but refused to allow him access to either sister, despite his threats of suicide and of running away to Switzerland should he be denied by Sally.71 Mrs. Pennington apparently relented enough, however, to promise Lawrence updates on the invalid’s condition.72

While dealing with Lawrence’s thoughtless behavior and Maria’s worsening illness, the Siddons family was once again reminded of the fragility of their eldest daughter. In September of 1798, Sally was struck down by yet another respiratory attack.

To the great increase of my cares and anxiety, she has been, for the last week, totally confined to her chamber, and her sweet faculties, for the greater part of that time, locked up by the power of that dangerous medicine, which alone relieves her from the effects of the dreadful constitutional complaint, for which there Appears to be no efficient remedy.73

Upon hearing of the seriousness of Sally’s attack, which required such high doses of laudanum that she was rendered unconscious for lengthy amounts of time,74 Lawrence wrote to Mrs. Pennington reassuring her of his devotion.

Never have I lov’d her more, never with so pure an ardour, as in the last moment of sickness I was witness of (the period she must remember), when, in spite of the intreaties [sic] of her dear Mother and Maria, I stole into her room, and found her unconscious of the step of friend or relation; her faculties ic’d over by that cursed poison, and those sweet eyes unable to interpret the glance that, at that instant, not apathy itself could have mistaken. No, my dear Mrs. P., if her days of sickness trebled those of health, still she should be mine, and dearer than ever to my heart, from the sacrifice of this distrustful and selfish delicacy to confidence and love; from this generous pledge of her esteem and trust in the heart of the man she loves.75

Although Mrs. Pennington was able to put Lawrence’s mind at rest with respect to Sally, Maria’s situation was increasingly desperate.76

By September, it was obvious that it was but a matter of time before Maria’s illness proved fatal. Mrs. Siddons, finally free of her theater commitments, arrived in Clifton on September 24 and moved her daughter across Dowry Square, via sedan chair, to her own lodgings. According to Mrs. Clement Parsons, Mrs. Siddons’s fame combined with the tragedy of the unfolding situation to provide the perfect fodder for the gossip columns of the society papers, and journalists jumped on the story as the word spread.77 Lawrence condemned these journalistic vultures who circled around the dying girl’s house in search of a story, writing to Mrs. Pennington, “those unfeeling Blockheads, the Newspaper Writers, have been torturing us with the death at full length. Would to God there was a penalty that might teach them humanity!78

Had these journalists only been privy to the drama unfolding in Maria’s sickroom, their prurient interest would have been satisfied. Maria’s final moments were not only filled with the ravages of disease, but she remained determined to end the connection between Sally and Lawrence. Mrs. Pennington’s correspondence confirmed Lawrence’s worst fears: “in her dying accents—her last solemn Injunction was given & repeated some Hours afterwards in the presence of Mrs. Siddons.79 These deathbed pronouncements were solely concerned with Sally’s future, or more correctly with preventing Sally’s marriage to Mr. Lawrence. According to Mrs. Pennington, Maria entreated, “Promise me, my Sally, never to be the wife of Mr. L—I cannot BEAR to think of your being so.” Sally tried her best to avoid making such a promise, and attempted to distract her sister from her purpose saying, “dear Maria, think of nothing that agitates you at this time.” Maria denied that the subject upset her, “but that it was necessary to her repose to pursue the subject.” When Sally said “Oh! it is impossible,” by which she meant that she was unable to “answer for herself,” Maria took the exclamation to mean that it was the marriage that was impossible and responded, “I am content, my dear Sister, I am satisfied.80 Maria had placed her sister in an untenable position, claiming that she was only acting out of concern for Sally’s welfare. Yet Sally was now in an insupportable situation, one made more so by the exchange with Mrs. Siddons that followed.

When Mrs. Siddons returned to Maria’s side, the girl, according to Mrs. Pennington, “desired to have Prayers read & followed her angelic mother, who read them, and who appear’d like a blessed spirit ministering about her, with the utmost clearness, accuracy, & fervor.81 Maria’s mind did not long remain on her devotions, however, as she turned once again to the subject of Lawrence. She implored her mother to ensure that he had done as promised and destroyed her letters.

“That man told you, Mother, he had destroy’d my Letters. I have no opinion of his honor, and I entreat you to demand them” … She then said, “Sally had promised her NEVER to think of an union with Mr. L” & appeal’d to her Weeping Sister to confirm it—who, quite overcome, reply’d—“I did not promise, dear, dying Angel—but I WILL & Do, if you require it.”—“Thank you, Sally; my dear Mother—Mrs. Pennington—bear witness. Sally, give me your hand—you promise never to be his wife—Mother, Mrs. Pennington—lay your hands on hers” (we did so).—“You understand? bear witness.” We bow’d, & were speechless. —“Sally- sacred, sacred be this promise “—stretching out her hand, & pointing her forefinger—“REMEMBER ME, & God bless you!82

And so it was done. As Sally could not honorably deny her sister’s final request, she asked Mrs. Pennington to make it clear to Lawrence that she intended to abide by her promise. “And what after this my Friend, can you say to SALLY Siddons? SHE has entreated me to give you this detail—to say that the impression IS sacred, IS indelible—that it cancels all former bonds and Engagements—that she entreats you to submit, and not to prophane the present awful season by a murmur.83 Maria finally succumbedto consumption on October 7, 1798 and was buried on October 10 at the old Parish church (St. Andrews) in Clifton.84

Mrs. Pennington’s recounting of Maria’s illness and death to friends, family, and erstwhile suitors broadly conformed to the general expectations of consumption in the sentimental tradition. Even a month before the end, she was applying sentimental rhetoric to Maria’s illness, describing her decline in the following manner: “The Lamp emits each day a rather more feeble ray. Yet all is lovely and interesting!85 Mrs. Pennington’s detailed descriptions of Maria’s final hours revealed the difficulties faced by those seeking to accommodate the dominant representations of consumption, which tended to rest on stylized description, with the brutal progress of the disease. In a clear departure from the notion of a gentle death, she wrote of Maria that “her pains were almost incessant,” however, in the same sentence she also stated that “her intellects seemed to gain strength & clearness.86 Thus, despite occasionally delving into the terrible realities of a death from consumption, Mrs. Pennington mostly stuck to the sentimental script. In a letter written the day after Maria’s death, Mrs. Pennington described a deathbed scene worthy of the best novel, as well as one in keeping with the tradition surrounding tuberculosis. “If ever Creature was operated on by the immediate Power & Spirit of God,” she wrote, “it was Maria Siddons, in the last 48 hours of her life.87

Maria’s disease and death were also accorded a full measure of beautification, although the reality was quite different. Up until the very end, Maria’s beauty had been unquestioned and her countenance had only been referred to as interesting or lovely. However, in her final days, even Mrs. Pennington could not deny the devastation consumption had wrought upon the young girl, writing, “Not one trace of even prettiness remaining—all ghastly expression, and sad discolouration!!88 Despite this unflattering description, it was not the havoc produced by the disease that prevailed in Mrs. Pennington’s accounts of the final moments of Maria’s life. Instead, she wrote of the power of the disease to elevate the girl’s beauty beyond even what she had possessed in life. She told Lawrence, “Yet this dear, faded creature, in her latter hours, resumed a Grace & Beauty that, in true Interest, surpass’d her most blooming days.89 Indeed, she even went so far as to state that a few hours before her death Maria possessed a countenance “that the Painter or the Sculptor with all their art could never reach!90

Mrs. Pennington softened the truth of Maria’s death from tuberculosis by claiming it enhanced both her spiritual and physical attractiveness. This perceived power of consumption to beautify its victim, was common in the sentimentalized mythology of the disease and was one that Mrs. Pennington mined again and again in her letters to Lawrence.91 She wrote that Maria’s “last attitude! … was Beauty & Grace itself!!—Such a Serenity! Such a divine composure! She took leave of us all with tenderness unbounded.92 Despite her apparent serenity, there was an acerbic moment, as the subject of Lawrence once again cropped up. Maria laid her death at his door declaring, “Oh! my dear Mother, there will be no Peace but in breaking all tyes with that man. He has … been my death.93 Mrs. Pennington seemed to be in accord with this statement, believing that Lawrence bore some responsibility for the girl’s demise, and implored the painter to master his “Passions” and “let not Maria Siddons have died in vain.94 This link between a disappointment in love and consumption was a commonly cited cause of the illness and certainly part of the literary traditions involving the disease.95

Mrs. Pennington went a step further by comparing Maria’s death to those of a wealth of sentimental consumptive heroines. Writing, “we have read the death-bed scenes of Clarissa & Eloisa, drawn as they are by the Hands of Genius & embellish’d with all that skilful & powerful fancy … believe me they are faint Sketches compared with those last Hours [of] Maria Siddons, where Nature supplied touches that Art cou’d never reach.96 Clarissa and Eloisa were references to characters in Samuel Richardson’s novel of the same name, first published in 1748, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Eloise.97 The choice of Clarissa as comparison for Maria was particularly pertinent, as the heroine’s death from consumption embraced all the various traditions associated with that disease. Her death in the novel was an intricate composition that reflected the gendered debates surrounding consumption during the period. Although difficult to diagnose and lacking a clear articulation of the actual ailment, Clarissa was brought low by a variety of factors that point to the disease, including providing a role for grief as a cause of the affliction and the utilization of the term decline, which was a common metaphor for tuberculosis.98 Certainly, Margaret Ann Doody contends that consumption was the cause.99 While Clark Lawlor has argued that Clarissa’s consumptive death became an archetype in Britain, one that “combines a good death and the typically female death of pining for a lost love object in a form of Neo-Platonic ascension from secular to religious love.100 Clarissa’s death, he states, expanded the prescribed consumptive death beyond the older deathbed traditions to encompass not only the Protestant tradition of the “good death,” but also elements of sensibility by providing a role for love, melancholy, and the passions. For Lawlor, Clarissa provided the template for any future sentimental representations of the death of a female from consumption, and he asserts that, “by providing an extended process of aestheticised consumptive death, Richardson showed a new way of understanding the relationship between disease and gender.101 Clarissa’s deathbed, styled a “happy exit,102 was described in detail in the work. Witnesses remarked, “we could not help taking a view of the lovely corpse, and admiring the charming serenity of her noble aspect. The women declared, they never saw death so lovely before; and that she looked as if in an easy slumber, the colour having not quite left her cheeks and lips.103

Figure 6.4 Illustration for Richardson’s Clarissa, Plate 12. Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki (Germany, 1785). LACMA Image Library.

The accounts of the death of Maria Siddons drew upon a sentimental formula, grounded in a cycle of images and deathbed tableaux, literary and visual, reaching back to Richardson’s novel.104 Maria’s death moved all those who witnessed her final moments or heard of them. Hence, her loved ones constructed an illness narrative that spoke to the dominant representations of consumption, and there seemed to be a conscious decision on the part of family and friends to insert Maria into the sentimental traditions so prevalent in accounts of the disease, and in doing so to provide meaning beyond the rather sad end of a young girl. Mrs. Pennington’s reading of Maria’s illness would dominate all of the other posthumous accounts.

Although Mrs. Siddons was present for her daughter’s death, her impressions during the course of Maria’s illness came primarily from Mrs. Pennington’s and Sally’s readings of the situation. Like her friend, Mrs. Siddons also wrapped a blanket of sentimentality around her deceased daughter, writing to Mrs. Barrington twelve days after Maria’s death,

This sad event I have long been prepared for, and bow with humble resignation to the decree of that merciful God who has taken the dear angel I must ever tenderly lament the loss of, from this scene of certain misery to his eternal and unspeakable blessedness … Oh that you were here that I might be able to talk to you of a Death-bed. In dignity of mind & pious resignation, forsaking all that the imaginations of Rousseau of Richardson have given as in those of Gloria [Eloise] or Clarissa Winslow [Harlowe] —for this was I believe from the immediate power and inspiration of the Divinity himself.105

Mrs. Piozzi, the friend of both Mrs. Pennington and Mrs. Siddons, also provided a reading of Maria’s death that not only fully participated in the application of the rhetoric of the consumptive heroine but also consciously admitted to doing so. Mrs. Piozzi even went so far as to write to Mrs. Pennington that the death of Admiral Nelson would “not be half as much regretted as is the lovely object of your late attention.”

Every letter I receive … is filled with her praise, and breathes an unfeigned sorrow for her loss. Virtue well tried through many a refining fire, Learning lost to the world she illuminated, and Courage taken from the Island protected by her arms, excites not as much sorrow as Maria Siddons, represented to every imagination as sweet, and gentle, and soothing; as young in short, for in youth lies every charm.106

Just ten days after this letter, in which she fully participated in sentimentalizing Maria’s death, Mrs. Piozzi admitted to another correspondent that the representations and virtues granted posthumously to Maria Siddons may not have been entirely accurate and instead had been assigned in proportion to her “youthful beauty.” Again, Maria’s youth and beauty were integral in the readings of her consumptive death and Mrs. Piozzi wrote:

Have you seen the death of a charming girl in the papers, whose long and severe sufferings interest all her friends, and have half broken her sweet mother’s heart! Maria Siddons! More lamented, I do think, than virtue, value, and science all combined would be. But she had youthful beauty; and to that quality our fond imaginations never fail to affix softness of temper and gentle spirit, every charm resident in female minds.107

Other parts of Maria’s deathbed performance also call into question the sentimentalized aspects of her final days. Arguably her emotional blackmail of Sally into giving up any future with Lawrence was mean-spirited, petty, and vindictive, despite her professed motivation of protecting her sister. Maria’s aunt, Mrs. Twiss, conceded that Maria’s behavior had been less than noble at the end and labeled her actions as extortion; while Sally believed that Maria had been motivated “as much by resentment for him, [Lawrence] as care and tenderness for her.108 Despite the inconsistencies of Maria’s behavior with sentimental deathbed performances, and the acknowledgments of the conscious application of sentimental virtues to her final days and death, overwhelmingly the posthumous treatments of the young woman match the fanciful representations of a death from consumption in contemporary literature. In the end, Maria Siddons was laid to rest with an epitaph as sentimental as the descriptions of her death proved to be. It was crowned by a verse taken from Edward Young’s epic poem Night Thoughts (1742). “Early, bright, transient, chaste as morning dew, She sparkled, was exhaled, and went to Heaven.109

Mrs. Siddons’s grief did not end with Maria’s death, as Sally also succumbed to a chronic respiratory illness in March of 1803. Sally and Maria’s deaths affected the ways in which Mrs. Siddons viewed her remaining daughter, Cecilia, and she wrote to a friend, “alas! She [Cecilia] too has I fear that fatal tendency in her Constitution which has already cost us so many hours of afflicting Anxiety—She is at present quite well, but so was dear Maria too, at her age.110 In another letter in the summer of 1803, Mrs. Siddons once again lamented her daughters’ deaths and expressed a growing concern for her only remaining daughter.

Two lovely creatures gone; and another is just arrived from school with all the dazzling, frightful sort of beauty that irradiated the countenance of Maria, and makes me shudder when I look at her. I feel myself, like poor Niobe, grasping to her bosom the last and youngest of her children; and, like her, look every moment for the vengeful arrow of destruction.111

Fortunately, despite Cecilia’s beauty, this pronouncement proved untrue. Mrs. Siddons’ remaining daughter outlived her.

The chasm that existed between the gruesome biological manifestations of consumption and the comparatively positive representations employed as part of the socio-cultural strategies for experiencing that illness are evident in the assessment and representations of the death of Maria Siddons. The dichotomy between the reality of a consumptive death and the sentimentalized presentation of that end were apparent not only during Maria’s illness and death, but also in the reactions of her family. Sensibility melded with concepts of beauty and consumption to aid in orchestrating a disease experience and deathbed in which love, disappointment, constitution, and beauty were all explicitly linked in a manner consistent with the ever more powerful rhetoric of consumption.