CHAPTER 3

‘Among them was a man of immense knowledge’

530–500 B.C.

At the beginning of the seventh decade of the sixth century B.C., a vessel with Pythagoras on board sailed across the waters west of Tarentum towards the toe of the Italian boot and the port city of Croton. The date is the best established in Pythagoras’ life. One of the most reliable of the earliest sources, Aristoxenus of Tarentum, gave it as 532/531 B.C.[1] Just short of a promontory where Croton’s men and women worshipped at their own sanctuary of the goddess Hera, the ship came into harbour. The passengers disembarked at docks bustling with other voyagers, slaves, sailors, and craftsmen and labourers from the shipyards, for Croton was a major port and shipbuilding centre in this region of the Mediterranean. Goods traded or transferred there came from up and down the coasts of the Italian peninsula, not only from the Greek cities but also from the Latin communities farther north and from numerous other regions of the Mediterranean.

There have been few archaeological excavations within the city of Croton proper. Modern Crotone covers the ancient Croton of Pythagoras, and frustrated archaeologists have to content themselves with sporadic work during the excavation of foundations for new buildings. Nevertheless, enough is known to allow for an idea of the arrangement of the city as Pythagoras found it.1 Behind the harbour the ground rose steeply to a hill where Achaean settlers had first built their homes two centuries before his arrival. This hill had later become an acropolis until Crotonians began lavishing more attention on the temple of Hera on the promontory. Sixth-century B.C. Croton apparently included three large blocks of houses oriented perpendicular to the coastline with a divergence of 30 degrees between them, an impressively geometrical layout but not unusual in its time, as evidenced by the Geomoroi. Pythagoras walked in narrow streets precisely aligned and crossing at right angles with narrower lanes isolating individual houses. Crotonians had constructed these buildings of rough blocks of stone, sometimes unbaked bricks, roofed with tile, with large pieces of pottery and tiles protecting the wall footings. They lived in rooms clustered around courtyards, with almost no windows facing the streets and lanes. A man who had also experienced Babylon would have drawn the impression that the people of Croton were more trusting and friendly than those who lived in similar houses there, for entryways in Croton opened straight into the courtyard.

Pythagoras may not have been a complete stranger here, for Croton’s harbour and shipyards were on the coastal sea route from Greece to the Strait of Messina, Sicily, and the Tyrrhenian Sea, and there were stories connecting his merchant seafarer father with the Tyrrhenian coast. The climate in Croton was magnificent and the region famous for being particularly healthful. The sea was not the opaque cobalt of Pythagoras’ native waters, but a transparent, cheerful blue, and the coastline seemed infinitely long, for every rise in the terrain revealed curving bays and coves and headlands as far as the eye could see. Forests clothed the low hills and some of the headlands and the shores of coves near the city, and grew thickly in the mountains on the northern and western horizons. Trees were one of Croton’s most valuable economic resources, as they were for Samos, providing timber for the shipyards.

Pythagoras surely knew that his new city had produced at least one amazing athlete and a fine medical man. Croton’s Olympic successes made her the envy of the Greek world, and no young Greek, no matter how sequestered in intellectual pursuits, could have escaped knowing about this athletic preeminence. Every four years, the city’s athletes voyaged east to Olympia in mainland Greece to compete, and from about two decades before Pythagoras’ birth had enjoyed a continuous spate of triumphs. Milo of Croton won the wrestling competitions in six Olympic games, covering a span of at least twenty-four years – a long success streak for any athlete, ancient or modern – and at six Pythian Games, a similar competition at Delphi.[2] Everyone had heard how he had hoisted an ox onto his shoulders and carried it through the stadium at Olympia. In the field of medicine, Democedes of Croton had practised in Athens and become physician to Samos’ tyrant Polykrates. Such was Democedes’ reputation and success that he would later be employed by the Persian Darius the Great. However, if Pythagoras had indeed heard – as Iamblichus reported – that in Croton men were ‘disposed to learning’, that must have meant they were ‘ready to learn’, for Croton was not yet renowned for scholarship or thought.

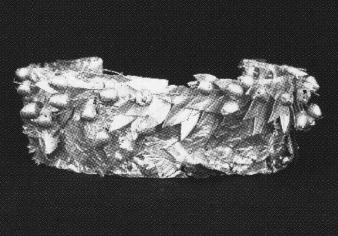

Croton’s most important religious site, Hera Lacinia, was situated on a promontory at the end of a peninsula that jutted out into the sea near the town. When Pythagoras first arrived, major construction at the temple had only barely begun, if it had begun at all, but soon the buildings at Croton’s temple of Hera would rival Samos’ temple to the same goddess. The treasures would include one of the most beautiful items still surviving anywhere from the ancient world, a diadem of exquisitely worked golden flowers, now in a glass case in Croton’s museum. Pythagoras may have seen it wreathing the head of the goddess’ statue. Crotonian donors to the temple were wealthy, cosmopolitan citizens who venerated her, the mother of Zeus, as the protector of women and all aspects of female life, and as Mother Nature, who looked after animals and sea travellers.

Hera’s golden diadem, dating from the sixth or fifth century B.C., from the temple of Hera Lacinia at Croton

Crotonians ruled their city in a manner that must have seemed blessedly old-fashioned to a man accustomed to living under Polykrates. The government was an oligarchy, as Samos’ had been before the tyranny. They called themselves the Thousand, and all of them claimed descent from colonists who had come two centuries before Pythagoras from Achaea, on the Greek mainland. The population there had outgrown the arable land in narrow mountain valleys and, led by a man named Myskellos, had taken ship to the west to try their luck around the gulf between the toe and the heel of the Italian boot.2 They were not ‘colonists’ in the sense of remaining subservient and connected to a mother country. What was true for many Greek cities – though no definition fit all – was true for Croton and her neighbours: ‘hiving off’, as happens with bees, was a better descriptive word than ‘colonisation’. Greeks of the independent maritime cities of southern Italy and Sicily had done well to leave their tight mainland valleys and were likely, in Pythagoras’ time, to be as rich and cosmopolitan as those who lived in Athens. Archaeological finds show that Myskellos’ settlers were not the first people to live at Croton, but had pushed the earlier inhabitants into the hinterlands and mountains.

Relations among the cities around the instep of the boot were often antagonistic, but Croton was apparently not walled or fortified. Perhaps the considerable distances between the cities made that unnecessary. Nevertheless, Crotonians visited the other communities. They might have hesitated to go to Sybaris, Croton’s chief rival and enemy during Pythagoras’ time, basking in ‘sybaritic’ languor on a broad, fertile coast-al plain about seventy miles to the north. However, stories placed Pythagoras on several occasions in Metapontum, another seventy miles north of Sybaris. Both Sybaris and Metapontum had been, like Croton, Achaean settlements, while Spartans had settled Tarentum, about thirty miles beyond Metapontum following the coastline, or 140 miles across the water from Croton. The people who lived in these cities may have clung to some identity as Achaean or Spartan, but the wider Greek world lumped them together as Italiotai, while neighbours to the northwest, in the Latin and Etruscan regions, called them Graeci. To the Greeks the region was Megale Hellas; to the Latins, Magna Graecia. In the end the Latin name would stick, because one of those Latin neighbours, about 350 miles northwest on the western side of the peninsula, was Rome, destined later to dominate the entire region and much of the western world and near east.

Those who lived in southern Italy at the time of Pythagoras had no premonition that some unusually ambitious construction projects in Rome – transforming a small, centuries-old community into a city designed on Etruscan lines, outgrowing one hilltop after another and expanding down the slopes into marshier territory, draining the swamps in the valley and paving it to make a forum – were only the first manifestations of a proclivity for building and conquering and expanding that would eventually make Magna Graecia seem a near suburb. Greek historians took no notice of Rome until she was in the process of completing her conquest of the Italian peninsula, 250 years after Pythagoras. Rome, for her part, was too busy with city planning, building, and wars during Pythagoras’ lifetime to take much notice of what was happening in Magna Graecia. However, as Rome emerged as a world power, she would create for herself a tradition and history that traced her ancient ancestry to Greece’s enemies at Troy, the Trojans, and made Pythagoras the teacher of one of her early kings, Numa. Pythagoras surely did not teach Numa, who died well before his birth, but well-educated Romans could not bring themselves to believe that their ancestors in Pythagoras’ time knew nothing about this great sage. However, though Croton and her neighbours were trading actively and as equals, probably even superiors, with Rome and other Latin and Etruscan centres, Croton’s more important friends and foes were closer to home on the southern coastline and in the wider Aegean and Mediterranean seafaring world to the east, south, and west. As the crow flies, and even by the more circuitous but safer coastal sea route, Croton was nearer to the Greek mainland than to Rome.[3]

Pythagoras was about forty years old when he settled in Croton, where he would live for about thirty years. He rapidly gained respect and soon was gathering a loyal group of associates into a society that bore his name and treated him with reverence. ‘He said it himself’ became a proverb among them – the last word on any subject. Those who joined him included ordinary citizens, noblemen, and women.

Iamblichus and Porphyry based their descriptions of Pythagoras’ approach to the people of Croton on the writings of a pupil of Aristotle named Dicaearchus, one of the earliest sources available to any Pythagoras scholar. Originally from Messina in Sicily, a short voyage from Croton, Dicaearchus was at the height of his career in 320 B.C., about 180 years after Pythagoras died. When Iamblichus added details – and he included more than Porphyry or Diogenes Laertius – he gave no indication where he got them. The impression is that he could safely assume his readers knew – or thought they knew – a great deal about Pythagoras. The name was the equivalent of modern figures who can be mentioned in the news or a sitcom, even in caricature, with no need to explain.

There was a possible lost source of information about Pythagoras’ years in Croton that would add credibility to the details of the tradition, if one could be certain it existed. The most sceptical scholars disdain it, while others point out that it is improbable that it did not exist. Porphyry thought it did. Referring to a time after Pythagoras died and many of his associates had been killed, he wrote:

The Pythagoreans now avoided human society, being lonely, saddened and dispersed. Fearing nevertheless that among men the name of philosophy would be entirely extinguished . . . each man made his own collection of written authorities and his own memories, leaving them wherever he happened to die, charging their wives, sons and daughters to preserve them within their families. This mandate of transmission within each family was obeyed for a long time.3

Such journals, as Porphyry implied, possibly gave the semi-historical tradition a better footing in fact than it would otherwise have had and were responsible for its being strong in details many of which are not the sort identifiable as the usual stuff of pure legend. Weighing against their existence is the fact that some pseudo-Pythagorean books later claimed to be such journals, and these forgeries may have been responsible for Porphyry’s, and others’, faith in the journals’ reality. On the other hand, the existence of fictionalised journals does not necessarily mean there were no authentic ones, only that there was a strong rumour there had been, and that the claim to be a Pythagorean ‘memory book’ could make a book a sure sell.

In Iamblichus’ account, probably taken from Dicaearchus, Pythagoras began his approach to the Crotonians by conversing with some of the youth of the city whom he met in the gymnasium. There could hardly have been a surer way to endear himself to their elders than by advising young people to honour their parents, practise temperance, and cultivate a love of learning, but Pythagoras must have had amazing charisma, for such teaching seems unlikely to have aroused enthusiasm among the young.

Hearing of him from their sons, members of the Thousand invited Pythagoras into their assembly to share any thoughts that would be advantageous to Crotonians in general. Such an invitation was not unusual in a Greek city, especially when a man’s pedigree in his native country was as unimpeachable as that of any of the local worthies. The Apostle Paul, soon after his arrival in Athens, was similarly invited to speak before the Areopagus, where Athenians and foreigners ‘spent their time talking about and listening to the latest ideas’.4 In a cosmopolitan city like Croton, high-ranking citizens were eager to meet a man recently arrived from an even more cosmopolitan area abroad.

Pythagoras complied with the request. Some of his advice (as reported by Iamblichus) was predictable, some unusual: Build a temple to the Muses to celebrate symphony, harmony, rhythm, and all things conducive to concord, he proposed. Symphony, harmony, and concord were going to be central to Pythagorean doctrine, and also to the neo-Pythagoreanism of Iamblichus’ era. Consider yourselves the equals of those you govern, not their superiors, Pythagoras advised the rulers. Establish justice, with members of the government taking no offence when someone contradicts them. End procrastination. At home, make a deliberate effort to win the love of your children, for while other compacts are engraved on tablets and pillars, the marital compact is made incarnate in children. Never separate parents from their children – the greatest of evils. Avoid sexual relations with any other than a marital partner. If you seek an honour, seek it as a racer does, not by trying to injure competitors but merely by trying to achieve the victory for yourself. If you seek glory, strive to become what you wish to seem to be.

The simplicity and charm of this list – and its lack of pomposity – lend it an air of authenticity. These teachings may merely have been Iamblichus’ late-Roman ideas put in Pythagoras’ mouth, but it was the sort of advice that would have been remembered in an oral history or memory book and would have appeared, either from earlier Pythagorean sources or newly minted, in the teachings of the various groups that considered themselves Pythagorean in the centuries separating Pythagoras from Iamblichus. Iamblichus’ account goes on to say that the elders were impressed. They built the temple and many sent their concubines packing. They asked Pythagoras to address the young men in a formal setting, and also to address the women of the city, whose inclusion was a strong theme in the Pythagorean tradition.

In Pythagoras’ address to the young men, said Iamblichus, he repeated what he had taught those he met in the gymnasium, adding that they should not revile anyone or revenge themselves on anyone who reviled them, and that they should practise listening, as a way of learning to speak. Iamblichus interjected a personal opinion that because of these moral teachings to the youth, Pythagoras really did deserve to be called divine.

In Pythagoras’ address to the women, wrote Iamblichus, he expressed high regard for female piety – particularly important in a city whose goddess was connected with all matters pertaining to women. He recommended equity and modesty and appropriate offerings rather than blood and dead animals or anything extravagant. Women should be cheerful in conversation and behave so that others could speak only good of them. A woman should know that it was all right to love her husband more than she loved her parents. She should not oppose her husband, but apparently it was acceptable to discuss matters with him and disagree, because Pythagoras said that if her husband gave way to her, she must not overinterpret that and think he had made himself subject to her. Again Iamblichus reported success that seems too good to be true: Marital faithfulness in Croton became proverbial. Women offered their costliest garments in the temple of Hera.

Though Iamblichus went into greater detail than Diogenes Laertius or Porphyry, the latter two were not silent when it came to what Pythagoras taught the Crotonians. Diogenes Laertius reported a teaching Iamblichus failed to mention: Some men have a ‘slavish disposition’ and are ‘born hunters after glory’, like men in a Great Game contending for prizes. Others are covetous, like those who come to the game for ‘purposes of traffic’. Others are spectators. These are the seekers after the truth. Twenty-six centuries after Pythagoras (and about seventeen after Diogenes Laertius), Bertrand Russell would make much of this Pythagorean distinction. Diogenes Laertius also mentioned Pythagoras’ advice not to pray for specific things, because you do not know what is good for you.

Iamblichus summed up Pythagoras’ teaching in what he called the ‘epitome of Pythagoras’s own opinions’, which he would continue to stress in private and in public: one should by all means possible amputate disease from the body, ignorance from the soul, luxury from the belly, sedition from the city, discord from the household, and excess from all things whatsoever. Iamblichus also praised Pythagoras’ teaching method – not to spout facts and precepts but to teach things (such as the power of remaining silent) that would prepare his listeners to learn the truth in other matters as well.

Porphyry described the splendid physical impression Pythagoras made: ‘His presence was that of a free man, tall, graceful in speech and in gesture.’ He was ‘endowed with all the advantages of nature and prosperously guided by fortune.’[4]

Iamblichus numbered the followers who soon gathered around Pythagoras at six hundred. Members of the brotherhood were advised to regard nothing as ‘exclusively their own’, wrote Diogenes Laertius. Friendship implied equality. They were to own all possessions in common and bring their goods to a common storehouse. Apparently, to judge from an incident later, in Syracuse, a good many Pythagoreans complied with this advice. Because of this ‘common sharing’, Pythagoras’s followers became known as Cenobites, from the Greek for ‘common life’.

However, not all Pythagoreans had equal status within the community. The six hundred were Pythagoras’ ‘students that philosophised’, wrote Iamblichus, Porphry, and their source, Nicomachus. There was a much bigger group, called the Hearers, about two thousand men who along with their wives and children would gather in an auditorium ‘so great as to resemble a city’ and built for the purpose of coming to learn laws and precepts from Pythagoras. It hardly seems a practical possibility that these people, presumably including many of Croton’s most prosperous, influential citizens, all ‘stopped engaging in any occupation’. However, according to the three biographers they did all live together for a while in peace, they held one another in high esteem, and they shared at least a portion of their possessions. Many, it seems, revered Pythagoras so greatly that they ranked him with the gods as a genial, beneficent divinity, but Iamblichus observed that, contra Nicomachus’ account, they perhaps did not all think of Pythagoras quite as a god. In his treatise On the Pythagoric Philosophy, Aristotle wrote that the Pythagoreans made a distinction among ‘rational animals’: There were gods, and men, and beings in between like Pythagoras.

When Pythagoras first arrived, Croton was at a low ebb of military prestige and clout. The communities of Magna Graecia were in a chronic state of conflict, internal and external, each attempting with varying success to dominate and enslave the next. The latest dismal chapter in this story had been Croton’s embarrassing defeat by the army of the city of Locri at the Sagras river, a few miles to her south. Iamblichus called Croton ‘the noblest city in Italy’, but in 530 B.C. she was licking her wounds from that disaster, while Sybaris was still a jewel in the crown of Greek colonial cities.

Croton nevertheless controlled considerable territory. Her normally acknowledged chora extended at least as far as what are now the river Neto to the north, in the direction of Sybaris, and the river Tacino to the south. The coastal lands between those two river mouths (with the city centred between) were hers, and away from the coast Croton’s territory extended into the mountains, where the tributaries of the two rivers originate among precipitous slopes and deep, narrow valleys[5] reminiscent of the early colonists’ homeland in Achaea. In the two centuries since Myskellos had brought those settlers, the coastal forests had begun to disappear, and the farmlands most vital to the life of Croton’s people were large clayey plains to the south of the city, watered by numerous springs and two more rivers and divided into farmsteads that cultivated wheat and cereals. Other cleared areas to the north were suitable for livestock.

Inevitably a community expected a man like Pythagoras to assume a public role, and he and his associates soon did, either by advising the oligarchical leaders or as part of the oligarchy. They became influential, probably extremely so, not only in the city and its environs but in other communities of the region. Porphyry reported that Pythagoras was so extraordinarily persuasive that Simicus, the tyrant of Centoripa, ‘heard Pythagoras’s discourse, abdicated his rule, and divided his property between his sister and the citizens’. Local lore still today agrees with the early historians that Pythagoras inspired a love of liberty in the cities of Magna Graecia and restored their individual independence, and that he and his followers were so successful in rooting out partisanship, discord, and sedition, and in establishing just laws, that the cities flourished in peace for several generations and became models for others before again falling into disputes and warfare. ‘Love of liberty’ may be a later ideal attributed with hindsight to the Pythagoreans. Political thinking during Pythagoras’ period in the Greek world saw good government not in terms of how much liberty was allowed but in terms of order and the well-being of the community.5 Diogenes Laertius had information that Pythagoras gave the Crotonians a constitution, and that he and his followers were an ‘aristocracy’ in the highest, literal sense of the word: ‘rule by the best’.

In 510 B.C., twenty years after Pythagoras’ arrival in Croton, Milo, of Olympic wrestling and ox-toting fame and by then a follower of Pythagoras, led Croton’s army against her opulent neighbour Sybaris. Like a latter-day Thales, Milo reputedly exercised his own brand of military hydraulics, diverting the river Crathis to flood the enemy city, and the army of Pythagorean Croton razed Sybaris to the ground. Modern Sibari occupies a different site from Greek Sybaris. Because the more ancient Sybaris perished forever with the defeat by Croton, the archaeological site there, buried beneath a Roman town and part of the Appian Way, has yielded a treasure trove of artefacts. Among them are covered pots from the seventh century B.C. the size of modern sugar bowls, whose lids are decorated with what later would be called Pythagorean triangles. It was a super-wealthy, cultured – indeed, ‘sybaritic’, – city that Milo destroyed, but though archaeologists have done extensive work, the only trace visible to modern visitors is a water-filled hole beneath excavations of the Roman town.

With Sybaris gone, Croton’s influence and power in the region reached a zenith, and historians credit Pythagoras and the teaching and training he initiated with bringing about this rise in Croton’s fortunes. If Diogenes Laertius, Porphyry, and Iamblichus are to be believed – and modern scholarship does not say them nay – he was an ancient example, and arguably the most successful one in history, of Plato’s ‘philosopher king’.

Or was it all a sham? There is a darker version of the tradition that has Pythagoras and his followers ruling in an autocratic, repressive way. In this retelling, the war with Sybaris began when Croton, at Pythagoras’ insistence, gave sanctuary to five hundred citizens of Sybaris who had been stripped of their property and banished. A social reform in Sybaris had justifiably confiscated the excessive wealth of these five hundred and distributed it to the poor, and Pythagoras’ sympathy for the formerly rich exiles revealed him in an unfavourable light as a defender of an autocratic and repressive status quo. This story does not actually conflict with the reputed egalitarianism of the Pythagoreans, for there is no evidence that their egalitarianism applied to society in general outside the Pythagorean brotherhood. No one knows what reasons Pythagoras might have had for wishing to restore the status quo in Sybaris, or whether his reforms in Croton were motivated by personal demagoguery, a desire to strengthen the aristocratic class structure, or a wish to transform the communities to conform to higher moral standards. All the early biographers – and fervent revolutionaries of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe – were sure it was the last.

Independent evidence speaks to Pythagoras’s impact on the economics of Croton.6 Numismatists credit him and his first followers with the introduction of a coinage with an incuse (hammered-in) design, the earliest coinage used in Croton and the area she ruled. These coins were both beautiful and difficult to create, and those familiar with the history of minting recognise the oddity and significance of their sudden appearance in this time and place, with apparently no gradual evolutionary process leading up to or explaining their emergence. The history of coinage does not normally work this way. Not that these were the first coins. There were earlier coins – for example, in Lydia, the region east of Miletus, before 700 B.C. But an innovation like the coins in Croton would seem to indicate a polymath – a ‘genius of the order of Leonardo da Vinci’, in the words of the historian C. T. Seltman.7 Given the area where the coins were used and the timing of their appearance, the inventor by default must have been Pythagoras, son of a prominent merchant with experience in a world-wide market, familiar (if his father was a gem engraver) with beautiful small design, and skilled with numbers. Aristoxenus, who had friends among the Pythagoreans of the fourth century B.C., wrote that Pythagoras introduced certain types of weights and measures but ‘diverted’ the study of numbers from mere mercantile practice, implying that Pythagoras also understood the use of numbers in connection with such practice. It is difficult to believe that he had nothing to do with the invention and introduction of the remarkable Crotonian coinage.

Though Pythagoras undoubtedly made serious enemies, for many years that seemed not to hamper him or his supporters very much. Pythagorean leadership extended the area Croton dominated much further both while Pythagoras lived there and in the fifty years after his death or exile – as far as Caulonia in the south (almost to the doorstep of the old enemy, Locri) and to the sanctuary of Apollo Aleo at Ciro Marina in the north (well on the way to Sybaris). The acquisition of Ciro Marina was something to be celebrated, since already at this early date it was famous for its fine wine. To the west, Croton’s influence extended almost to the Tyrrhenian Sea, to Terina. That was the best Croton would ever do. She was no Rome.

Porphyry, more than Iamblichus or Diogenes Laertius, stressed the silence of the Pythagoreans and recognised not only its value but also how disastrous it would prove for the Pythagorean tradition. It is frustrating to find that, though Porphyry mentioned Pythagoras winning over the Crotonian rulers and described the invitations to address the youth and women – and though it was Porphyry who identified Dicaearchus as the source of this information – he made no claim to be able to report with any certainty the details of what Pythagoras told his audiences. He attributed this lack of information to Pythagorean silence. Because all three biographers tended to err on the side of believing their sources too readily rather than too little, Porphyry’s reluctance makes what he said on the matter of Pythagorean silence particularly credible. According to him, Pythagoras and those who followed him during his lifetime did not reveal their ideas, principles, or teachings, or the details of their discipline to others. They wrote nothing down, keeping ‘no ordinary silence’. In great part because of this secrecy, much information about Pythagoras had come down through the centuries in scattered, fragmentary, hearsay form, consisting of what other people thought he and his associates taught and what their way of life was.

Porphyry was not alone in stressing Pythagorean silence. Diogenes Laertius made it clear that there were two kinds: On the one hand, ‘silence’ meant keeping doctrine secret from outsiders; on the other, it meant maintaining personal silence in order to listen and learn – and that applied especially among followers in ‘training’. For five years they were silent, listening to discourses. Only after that, if approved, were they allowed to meet Pythagoras himself and be admitted to his house. The advantage to be gained from remaining silent was an ancient theme that also appeared in the Wisdom chapters of the Hebrew Scriptures and was picked up by early Christian church fathers a few generations after Iamblichus.

Did the first type of silence extend to putting nothing in writing? Of the three third- and fourth-century biographers, Diogenes Laertius was the only one to insist that Pythagoras wrote down some of his doctrines, but the section of his biography titled ‘Works of Pythagoras’ is confusing and unconvincing. He began on shaky ground with the words:

Some say, mistakenly, that Pythagoras did not leave a single written work behind him. However, Heraclitus the natural scientist pretty well shouts it out when he says: ‘Pythagoras, son of Mnesarchus, practised inquiry more than any other man, and selecting from these writings he made a wisdom of his own – a polymathy, a worthless artifice.’

It would seem, contra Diogenes Laertius, that what Heraclitus ‘shouted out’ was that Pythagoras could read and plagiarise, not that he wrote anything down. Diogenes Laertius was right, however, that Heraclitus’ words were worth careful scrutiny, because his lifetime probably overlapped Pythagoras’ and his comments about him are among the oldest that survive. Though in Heraclitus’ own philosophy he often sounded like a Pythagorean, if he ever had anything good to say about Pythagoras there is no record of it. He had little better to say about anyone else. He was contemptuous of most of humankind, and in particular of polymaths, coming out with such disparaging remarks as ‘Much learning does not teach thought – or it would have taught Hesiod and Pythagoras, and again Xenophanes and Hecataeus.’ Be that as it may, there is no reason to take Heraclitus’ diatribe as evidence that Pythagoras wrote a book.

Diogenes Laertius was not equally convinced about all claims for Pythagoras’ authorship, but he believed that Pythagoras had written three books that still existed in his lifetime. If so, they then rapidly disappeared or were discredited, for Porphyry, only a few years later, wrote, ‘He left no book’. There was plenty of reason to be sceptical about the authorship of the books that Diogenes Laertius listed, considering the number of Pythagorean forgeries that had appeared during the Hellenistic and Roman eras. However, information that Pythagoras wrote poems under the name of Orpheus came from an earlier, more reliable source. Ion of Chios, a scholar, playwright, and biographer born shortly after Pythagoras died, tried to determine the true source of some poems that were widely supposed to have been written by Orpheus. He decided that the author was Pythagoras and that Pythagoras had attributed them to Orpheus.

[1]Iamblichus linked the date with the Olympic victory of Eryxidas of Chalcis, his own home city. Diogenes Laertius agreed that it had to have been between 532 and 528 B.C.

[2]Milo is also known as Milon. His name has come to symbolise extraordinary strength. He was the most famous wrestler in the ancient world.

[3]In the twenty-first century, 2,600 years later, the people of former Magna Graecia still do not totally identify with the modern, centralised Italy. Old attitudes and identities die hard.

[4]Porphyry said he got this information from Dicaearchus.

[5]In some of the remoter villages of those mountains, the people in the twenty-first century still speak a form of Greek that linguists identify as neither modern Greek nor the Byzantine Greek that arrived with Byzantine Christian Greeks in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, but as an ancient form of the language that is spoken almost nowhere else in the world.