Photo Insert

The Scottish songwriter, poet, and journalist Charles Mackay is best known as the author of Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. First published in 1841, it is still in print. Wikimedia Commons.

The illegitimate son of a small town mayor, Jan Bockelson had charisma and theatrical skills that propelled him into the leadership of the catastrophic 1534–1535 Münster end-times rebellion. Courtesy of Stadtmuseum Münster.

The tongs used to torture Bockelson and his lieutenants, and the cages in which their bodies were hung from a church tower. The cages are still visible today. Courtesy of Stadtmuseum Münster.

Nature endowed John Law with a steel-trap grasp of mathematics that enabled him to transform France’s banking structure and ignite the world’s first widespread stock bubble. Reviled in his time, he is now recognized as one of the forefathers of today’s paper-currency–based financial system. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

This 1720 Dutch cartoon depicts John Law as Don Quixote. Courtesy of Baker Library, Harvard University.

The Mississippi Bubble in Paris triggered a similar mania in London, the South Sea Bubble, whose central character, John Blunt, became the prototype of today’s arrogant and fraudulent CEO. Private Collection/Bridgeman Images.

“The South Sea Bubble, a Scene in ‘Change Alley in 1720,’” painting by Edward Matthew Ward, 1847. Digital photograph: Photo © Tate Gallery, London.

George Hudson, the indefatigable railroad magnate of the 1840s, simultaneously ruined thousands of investors and endowed England with the world’s first high-speed transport network. Wikimedia Commons.

Psychologist Peter Wason’s 1950s experiments established today’s widely quoted concept of confirmation bias. Courtesy of Armorer and Sarah Wason.

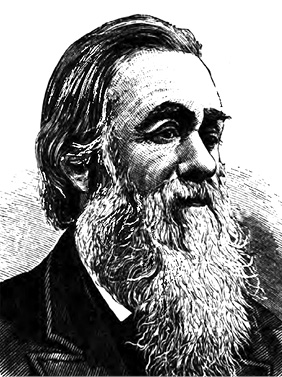

The early agnosticism of William Miller gave way to intense religious belief and fixation on the imminence of the end-times. Courtesy of the Adventist Digital Library.

The wealth, social connections, and organizational skills of Joshua V. Himes propelled Miller’s theology into a powerful mass movement. Courtesy of

the Adventist Digital Library.

Between 1842 and 1844, the end-times followers of William Miller organized 125 “camp meetings” attended by up to several thousand believers. The railroad companies often built special stations to receive attendees; preachers rode for free. Courtesy of the Adventist Digital Library.

The front page of The Midnight Cry! from October 19, 1844, three days before the world was to end. Courtesy of the Adventist Digital Library.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the iconoclastic economist Hyman Minsky described the instability inherent in a modern economic system built on financial leverage. Courtesy of Beringer-Dratch/Levy Economics Institute of Bard College.

During the 1920s, “Sunshine” Charlie Mitchell sold the unsuspecting customers of National City Bank, the predecessor of today’s Citicorp, billions of dollars of dodgy stocks and bonds. Wikimedia Commons.

A seasoned prosecuting attorney, Ferdinand Pecora questioned Charlie Mitchell so deftly that he incriminated himself, such that his tenure as chief counsel of the U.S. Senate’s Committee on Banking and Currency became known as the “Pecora Commission.” Wikimedia Commons.

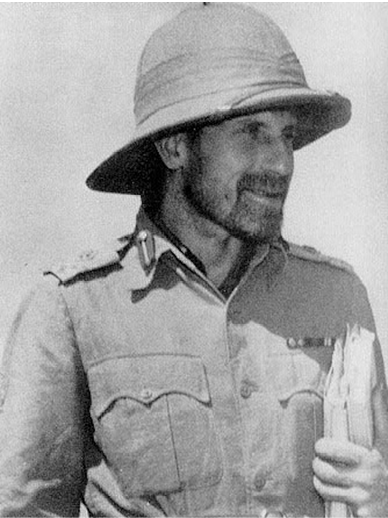

The British commando Orde Wingate deeply imbibed his family’s dispensationalist end-times theology and mentored many in the Israeli army’s high command, including Moshe Dayan. Wikimedia Commons.

In 1948, Moshe Dayan, the Israeli Jerusalem front commander, dressed himself in Arab garb and traveled by car with his opposite number, Abdullah el-Tell, pictured in the above photograph, to Amman for talks with the Jordanian king. Wikimedia Commons.

From left to right, the local Israeli commander, Uzi Narkiss, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan, and Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin stride into the Old City on June 7, 1967, in this iconic photo. The National Photo Collection of Israel.

Immediately following the June 1967 conquest of the Old City, the fanatical chief rabbi of the Israeli Army, Shlomo Goren, blew a ceremonial ram’s horn (shofar) at the Western Wall. Later, he unsuccessfully tried to convince Uzi Narkiss to blow up the Dome of the Rock. Wikimedia Commons.

A Seventh-day Adventist salesman with a third-grade education, Victor Houteff convinced himself that he alone had arrived at the proper interpretation of the Book of Revelation’s end-time sequence. Wikimedia Commons.

The sect eventually wound up under the leadership of Lois Roden, the widow of one of Houteff’s lieutenants. Wikimedia Commons.

The son of an unmarried fourteen-year old girl, Vernon Howell endured a chaotic childhood. After Lois Roden’s death, he changed his name to David Koresh (after, respectively, the Jewish King David and Persian King Cyrus), and led the sect towards its apocalypse in Waco, Texas, on April 19, 1993. Wikimedia Commons.

Fire erupts at the Mount Carmel Branch Davidian complex on April 19, 1993, killing 76. Timothy McVeigh witnessed the conflagration in person, and in revenge perpetrated the Oklahoma City bombing on its second anniversary, killing 168 innocents. Wikimedia Commons.

Ronald Reagan was an enthusiastic believer in apocalyptic dispensationalist theology, which he could knowledgeably discuss with its best-known leaders, such as Jerry Falwell, founder of the Moral Majority. White House/ Ronald Reagan Presidential Library via Wikimedia Commons.

During the tech bubble of the 1990s, this barber shop became the improbable center of stock speculation on Cape Cod, as proprietor Bill Flynn dispensed investing advice while clipping hair. Courtesy of the Wall Street Journal.

Between 1984 and 1993 a small-town ladies’ investment club in Beardstown, Illinois, reported mistakenly calculated returns that seemed to show them beating the market averages, launching its middle-aged members into media stardom. The LIFE Images Collection, Getty Images.

One of Islam’s holiest sites, the Temple Mount’s Dome of the Rock is thought by some Jews to be the site of Solomon’s First Temple. Jane A. Gigler.

Former Saudi national guard corporal Juhayman al-Uteybi, expecting the end-times and the return of the Prophet, launched a suicidal attack on Mecca’s Grand Mosque, Islam’s holiest site. This picture was taken shortly before he and several dozen comrades were executed. Wikimedia Commons.

The Palestinian Muhammad al-Maqdisi (left), deeply influenced by Juhayman al-Uteybi’s life and writings, in his turn inspired a large number of Islamic extremists, most notably the bloodthirsty Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, killed by a U.S. air strike in 2006. Al-Maqdisi renounced his end-times beliefs and today lives peaceably in Jordan. Getty Images News.

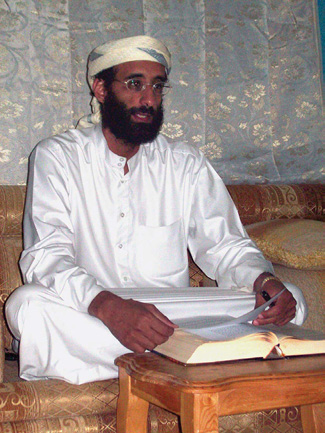

Yemeni-American Anwar al-Awlaki’s apocalypse-laden internet content inspired numerous terrorist attacks in the United States, most notably “underwear bomber” Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab and the Fort Hood shooter Army psychiatrist Nidal Malik Hasan. His videos continued to inspire deadly attacks even after his death in a 2011 drone strike. Wikimedia Commons.

The cover of Issue 2 of Dabiq, the highly influential Islamic State publication named after the site of a famous battle in 1516 fought against the Christian Byzantine Empire. This issue was published just after the declaration of the caliphate on June 29, 2014. Dabiq, Issue 2, Ramadan 1435 AH (June–July 2014).

From the same issue of Dabiq, a celebration of the demolition of the Ahmad Al-Rifa’i shrine in southern Iraq named after the founder of the Sufi order, a sect considered heretical by IS. Dabiq, Issue 2, Ramadan 1435 AH (June–July 2014).