Figure 1.1

Sales receipt for Alexander’s Notes on the Synthesis of Form, dated November 17, 1964.

1

Beginnings

Beginnings, I

Linkography is the outcome of a long chain of experiences that can be pinpointed only partially and only with hindsight. Some of these experiences can be described only in general terms; others have a precise timing attached to them. The very first of these events took place a long time ago, but the exact date can still be cited: On November 17, 1964, I happened to notice a copy of Christopher Alexander’s book Notes on the Synthesis of Form in a small bookstore in my home city, Jerusalem. Attracted to the book beyond resistance, I purchased it. The sales receipt is reproduced here as figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1

Sales receipt for Alexander’s Notes on the Synthesis of Form, dated November 17, 1964.

I was a beginning architecture student at the time, and I understood only part of what Alexander wrote, but it was reassuring to get a sense that designing is a structured process that can be explained and analyzed. Years later, I returned to Notes on the Synthesis of Form and reread it in its entirety. Decades later, I can now explain precisely what I found—and still find—so attractive about the book. I cannot, however, fully account for my intuitive response to it then, nor is there an explanation for the fact that the book had reached that little bookstore, in what was then a small, isolated, and rather provincial city, so soon after its publication.

In architecture school we learned how to design by doing it. We would come to class with our ideas drawn up, and we would get feedback from our teachers before making the next step or going back to modify our drawings. Alexander’s book revealed to me that designing can be clarified—that there is a logic to it, and that it is not pure magic. Furthermore, the process of designing can be researched. I will discuss Alexander’s contribution at some length in chapter 2; here I only want to make the point that when I first came across it I had a strong intuition that it was important and that I should make an effort to understand it.

Beginnings, II

A decade later, already an architect with some experience, I began to teach design. I spent many hours in the studio, trying to help students with their design projects. In my first few years of teaching, I taught students at different levels, mostly in first-year and second-year studios. It was impossible not to notice how their rates of learning, their thinking, and their reasoning varied, and how comments that were useful to one student were not necessarily helpful to another. This variation raised a lot of questions about thinking, reasoning, and learning in design, a field in which no amount of declarative knowledge can seriously shape the process of idea generation and in which procedural knowledge is mostly accumulated individually with experience. I knew I wanted to know more about how designers—novice and experienced—think, how they generate ideas, and how they put ideas to the test, combine them into something meaningful. Why are some designers better and more creative than others? What is it that a good or an experienced designer does that a less brilliant or novice designer does not do?

My experience in a design workshop for children in 1985 (see Goldschmidt 1994a) led to a number of insights into individual differences and about reasoning in general. It seemed that the children’s reasoning was not entirely different from that of professional designers, although the knowledge they possessed and used was obviously not the same. I realized that I would have to turn to psychology for some of the answers. I approached developmental psychologists, and discovered a fascinating world of research. Little by little, though, I came to realize that cognitive psychology was really the field I should look into. That realization opened a vast and wonderful treasure box.

At the same time, I reflected on my own design processes as a practitioner and, before that, as a student. Why was it sometimes difficult to generate good ideas? What was I doing right on some occasions and less so on others? The “front edge” of the design process—the race to secure good design ideas that are capable of “carrying” a design solution—became the topic I wanted to focus on.

Beginnings, III

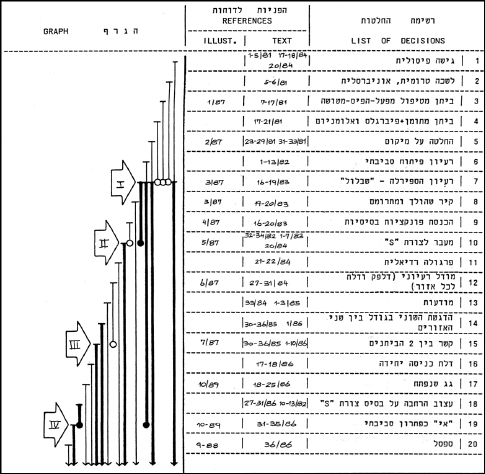

On a summer’s day in 1988, I was sunbathing next to the small swimming pool of the condo in which I was living in the Brighton neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts. I was on sabbatical at MIT and was working on my research for the National Endowment for the Arts, which was titled “Notation Systems for Processes of Designing.” I had the background written up, but an actual notation was yet to be devised. Hoping that the refreshing poolside environment would also refresh my thoughts, I sat there with my papers and stared at the water. The only precedent I could think of for the notation I had in mind was a notation my former student Eduardo Naisberg had developed for the purpose of representing students’ design decisions in the course of a short design process (see Naisberg 1986). An example of Naisberg’s notation is shown here in figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2

A representation of a student’s design decisions in the course of a two-week project. Each decision is listed in the right column (in Hebrew) and represented by a vertical line in chronological order in the left column. Decision lines are trimmed (that is, the end is marked by a circle) when decisions are withdrawn. Bold lines represent major decisions. Large arrows on the left indicate points of transformation in the composition of the main design concept. Source: Naisberg 1986, 132.

It was clear that Naisberg’s notation, elegant as it was, was not the solution to what I had been trying to achieve, but for a long time my experimentation with various other notations was unsatisfactory. I had been introduced to protocol analysis a short while earlier, and I found that method most appropriate and promising for the analysis of design processes at a fine granularity. I had also recently been introduced to cognitive psychology, which fascinated me and which provided a good framework for my interest in designers’ thinking processes. Thus, I decided to base a notation on parsed protocols. But none of the coding systems I came up with seemed to generate any meaningful insights. At the poolside in Brighton, I decided to let go of coding, and I experienced an “Aha!” moment. On the grid paper I had brought with me, I scribbled the first hesitant linkograph-like notation. The next day, I tried desperately to reproduce my crude pencil notation on my newly acquired Macintosh SE. The first attempts were rather frustrating, and it was quite a while before I could draw anything coherent on the Mac. For a long time I continued to use large sheets of grid paper, pencils, and erasers. The concept of the linkograph evolved and acquired depth and breadth with use; each time a problem or a deficiency was discovered, the system had to be augmented with new capabilities or re-inspected altogether. To this day, our means of producing linkographs, the digital linkographer, is far from perfect, but we use it anyway.

After an initial report to the National Endowment for the Arts, I presented linkography at a cybernetics conference in Vienna (Goldschmidt 1990). A great opportunity arose in 1994, when I was invited to participate in what would eventually come to be known as the Delft protocol workshop. A number of researchers in the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering at the Delft University of Technology, led by Nigel Cross, became interested in protocol analysis, which had become popular with researchers studying design thinking. They wanted to explore protocol analysis as a method for design research, and perhaps to plot its potential and its limitations. They invented a design task and went to Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center to experiment with it. The task was given to volunteer experienced designers, some working individually and some in teams, under similar controlled conditions. The sessions were videotaped. Two of the tapes (one representing the work of an individual and one the work of a three-person team), and the protocols that were transcribed from them, were sent to about two dozen design researchers who were experienced in protocol analysis, and they were invited to analyze the protocols by whatever method they wanted to use. When the analyses came in, the authors were invited to present them in a workshop. The fact that they all had worked from the same data made for very focused discussions. The papers that resulted were published in a special issue of Design Studies (volume 16, issue 2, 1995, guest edited by Kees Dorst) and in a book titled Analysing Design Activity (Cross et al. 1996). At the workshop, I presented a paper in which I used linkography to compare the process of the individual and that of the team (Goldschmidt 1995, 1996). On that occasion I discovered the potential of critical moves as a central feature of linkography.

Since then, progress has centered on details and further features of linkographs, but at the same time the theory behind linkography has been built up and the scope of its applicability has been extended. Somewhat unusually, the application preceded the theory to a large extent. In this specific case, research was very similar to design and was largely a bottom-up process that, by way of confirmation of experimental findings, also went back to theory in a top-down manner. That is, first there was the linkograph; its potential had to be discovered little by little. Tying it in with theory happened later. Of course, the initial reason for developing the “tool” had to do with theory, but this theory was largely implicit at first. I would claim that this hand-in-hand development of the “product” and its rationale was a typical design process. Therefore, it may be far from a chance occurrence that linkography was proposed by someone with a design background.

Chapter 2 of this book outlines the history of design thinking research in the last half-century, with an emphasis on the contribution of Christopher Alexander. Alexander published the most original, comprehensive, and well-thought-out work on design as a rational process wherein a problem is decomposed into subsets. The designer’s task is to remove any misfits among responses to the subsets. The “good fit” that is to be achieved is a very important concept that has implications for linkography. Chapter 2 also presents and discusses protocol analysis as the major methodology used in research on design thinking.

Chapter 3 focuses on what is taken to be the goal of the search that occurs at the “front edge” of the design process: a design synthesis. The synthesis is an idea, a concept, or a selection of ideas or concepts that can be used to support a comprehensive, coherent design solution—something that is possible only if the design acts that implement such ideas are in congruence with one another, or (to use Alexander’s term) if they display “good fit” among themselves. Generating, inspecting, and adjusting ideas is a process that evolves over a large number of small steps that I call design moves. From there it is a short step to a notion of a network of moves. The next step is the recognition of links among these moves as the manner in which a good fit is achieved. The notion of two modes of thinking, divergent and convergent, is also introduced in this chapter.

Chapter 4 describes the features and the notational conventions of the linkograph. It dwells on different kinds of moves and explains what aspects of the design process can be observed and measured in a linkograph. In addition to what may be referred to as the standard notation, a variant notation that has been proposed to replace or extend the standard linkograph is introduced.

Chapter 5 focuses on critical moves, arguably the most significant element in a linkograph. Critical moves are moves that are particularly rich in links. The chapter explains why this makes them important. The bulk of the chapter presents various studies in which critical moves are the key to investigations of specific topics related to design thinking.

Chapter 6 is devoted to design creativity—more specifically, to the creative process in design. Linkography is particularly well suited to the study of this important aspect of the design process. Here I return to divergent and convergent thinking and show how they are manifested in linkographs. Again, a number of cases are used to illustrate the points made.

Chapter 7 introduces thirteen linkographic studies conducted by other researchers who brought fresh insights to their investigations and reported interesting findings that extend the utility of linkography in many ways. These studies, which are quite varied, were selected in order to demonstrate the potential of linkography as a research tool in design thinking and beyond.

The book concludes with a short epilogue and an appendix that lists the main studies on which the cases discussed in the text are based.