CHAPTER 5: MONEY MATTERS

IT WAS GOOD FOR ME. WAS IT GOOD FOR YOU?

“The Completely Honest OB/GYN” is a character created by The Second City comedy troupe. He shoots straight no matter how awkward or unpleasant the truth may be. When a pregnant couple complains that he’s 45 minutes late for their appointment, he responds, “Those times are for patients, not for doctors.” When the wife says she wants a natural delivery, he asks, “Are you sure? Because a C-section would be way easier for me.”1

Might OB/GYNs really encourage cesarean sections (C-sections) for their own convenience? The folks at the Childbirth Connection think so. In a detailed discussion replete with citations to the public health literature, they point out that “a planned cesarean section is an especially efficient way for professionals to organize their hospital work, office work and personal life.”2 Like cars coming off an assembly line, C-sections are more predictable than natural deliveries, which can take unexpected twists and turns. C-sections are also significantly more profitable than vaginal deliveries, particularly on a per-hour basis. Does this explain why the C-section rate is so high? Thirty-two percent of deliveries are by C-section, but the optimal rate is estimated to be less than one-third of that number.3

Medical professionals deny that financial considerations influence their treatment recommendations. For many doctors, physician assistants, and other providers, this is true. For others, it is not. The evidence that financial compensation affects many providers’ medical practices is solid. Two economists found that, on average, a 2 percent increase in Medicare’s payment rate for a procedure generates a 3 percent increase in volume. The effect on elective procedures was especially pronounced. Higher Medicare payments also drove investments in technologies like magnetic resonance imaging scanners. Patients seem not to have benefited from more intensive, high-tech treatments: the measurable health benefits were negligible.4

Urology provides a case study of the connection between compensation and choice of treatments. In the 1990s and early 2000s, men with prostate cancer had several options, including two treatments designed to slow the growth of tumors by inhibiting the production of testosterone. One option was surgical removal of the testicles (orchiectomy). The other was a drug regimen known as androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Because the two treatments were equally effective, one would have expected the choice of procedures to be driven by considerations such as side effects, quality of life, or differences in recovery time.

In fact, men overwhelmingly chose ADT over orchiectomy. In 2003, Medicare shelled out at least $1 billion for ADT while spending a paltry $1.5 million on surgeries.5 The difference in the number of procedures was vast.

Because ADT was 10–20 times more expensive than orchiectomy, the preference for it inflated Medicare’s costs. But that was not the real problem. The problem was that ADT drugs were so profitable that urologists prescribed them to many men who did not need them. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that 40 percent of the patients who received ADT should not have.6 “Hundreds of thousands of men were chemically castrated for no reason; that’s the biggest scandal of all,” said Anthony Zietman of Harvard Medical School, who directs the radiation-oncology program for residents at Massachusetts General Hospital. “The money was too irresistible.”7 Medicare overpaid doctors for ADT drugs, so doctors prescribed them too often.

How profitable were these medicines? By prescribing them, urologists could make as much as $5,000 per patient.8 For some doctors, drug-related payments generated up to 50 percent of their revenues.9

ADT drugs were excessively profitable partly because of the phony average wholesale prices, discussed in Chapter 3, that two companies, TAP Pharmaceutical Products Inc. (TAP) and AstraZeneca LP, submitted for them. In some instances, urologists received even more money through hidden deals with these companies, which rewarded them for using their products and discouraged them from switching to a different brand. These deals were illegal, and heads rolled when they came to light. TAP and AstraZeneca collectively paid more than $1 billion in settlements, and several urologists went to jail.10

The scandal involving ADT drugs helped occasion the enactment of the Medicare Modernization Act (MMA) in 2003. The MMA greatly increased health care spending overall, but it took a nip out of payments for cancer drugs. By 2005, urologists were receiving less than half as much as they once did for administering the two most popular ADT drugs, Lupron and Zoladex.

Treatment practices turned on a dime. The frequency of ADT sharply declined while surgeries suddenly became more common. Yes, once reimbursement for ADT drugs dropped, urologists physically castrated their patients more often, making it clear that financial incentives for physicians had helped determine the treatments that patients received. And, because many men who would have been given ADT before now received no treatments at all, inappropriate use fell by 44 percent in a mere two years.11

RADIATING FOR DOLLARS

With the end of massive overpayments for cancer drugs, urologists went looking for new ways to make money. They were upfront about their reasons. In 2004, Urology Times, a trade publication, ran an article under the title “New ventures may help make up for lost reimbursement,” the point of which was that urologists were “turn[ing] to a variety of non-traditional income producers” in an effort to recoup revenues lost as a result of declining payments for ADT.12

Most of the new ventures involved invading other health care providers’ turf. For example, instead of sending a patient needing a computed tomography (CT) scan to a radiology lab, a urologist could buy a scanner, hire a radiologist, provide the service in-house, and capture the profit.

Since urologists routinely order CT scans for diagnosis of stones in kidney and ureters, with as few as three studies a day, an in-house CT scanner would pay for itself in about a year. In a hypothetical example of a pelvic scan without contrast, three studies a day would generate more than $163,000 over 5 years.13

The article encouraged urologists to consider performing lab work on blood tests and tissue samples in-house too.

Tucked inside the Urology Times article was another one with a punning lead: “IMRT may provide new stream for urologists.”14 This second article reported that “[u]rologists’ search for new revenue streams has led them to join forces with radiation oncologists in a venture aimed at capitalizing on the anticipated growth of intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) as a treatment for early-stage prostate cancer.”15 IMRT is fancy and expensive. Just what the doctors needed.

IMRT attacks prostate tumors with X-rays delivered in big doses from multiple angles. But it is not clearly superior to other prostate cancer treatment options, including active monitoring, surgical removal of the prostate, drug therapy, implantation of radioactive seeds, or external beam radiation therapy—a different radiation treatment. In fact, published studies suggest that for men with newly diagnosed, nonmetastatic prostate cancer, no therapy or approach is uniquely better than the others.16 All have pluses and minuses.

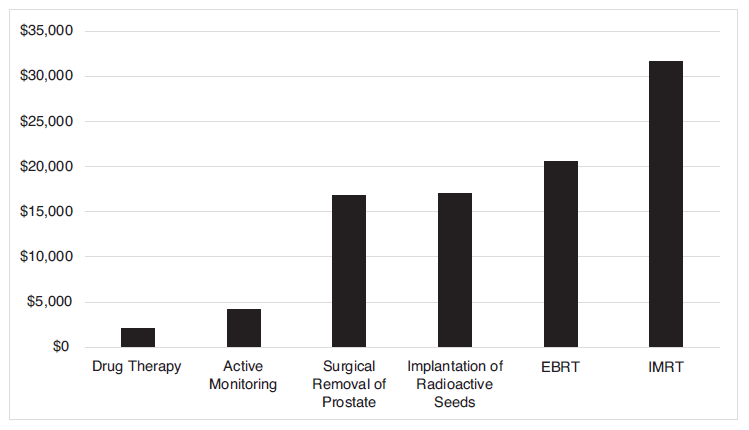

IMRT is, however, very expensive, as shown in Figure 5-1.17 In the words of Jean Mitchell, an economist at the McCourt School of Public Policy at Georgetown University who authored a leading study of IMRT usage, “Medicare is paying a lot of money for aggressive treatment of prostate cancer where it’s basically not going to change anything in terms of giving a patient more years of life.”18

The profitability of IMRT didn’t matter much to urologists when they had to refer patients needing it to radiation oncologists. The law prohibited oncologists from paying kickbacks for referrals, so urologists had relatively little financial interest in recommending IMRT. This changed when urologists hired oncologists and began offering IMRT in-house. Now, every IMRT treatment put money in a urologist’s pocket.

Figure 5-1. Cost of Alternative Treatments for Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer (2005)

Source: Jean M. Mitchell, “Urologists’ Use of Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy for Prostate Cancer,” New England Journal of Medicine 269, no. 17 (2013): 1629–37, http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa1201141.

Note: EBRT 5 external beam radiation therapy; IMRT 5 intensity modulated radiation therapy.

This side business pays doctors up to $40,000 per patient from Medicare, or 645 times what a urologist gets for a standard office visit, and as much as 20 times what the federal insurance program pays a surgeon to remove a cancerous prostate gland, according to published studies. Reimbursement from private insurers for IMRT can be even higher.19

As of 2010, about one in every five urologists offered IMRT in-house. The incentive to push patients into IMRT was obvious.

So was the effect on treatments. Doctors at Chesapeake Urology Associates in Baltimore, Maryland, referred about 12 percent of new prostate cancer patients for IMRT before the practice acquired its own machine in 2007. IMRT referrals then jumped to 43 percent. “In Horry County, South Carolina, IMRT referrals nearly doubled after the Myrtle Beach area’s main urology practice merged with the region’s largest IMRT clinic.”20 Overall, Mitchell found that, “[w]hen urologists have a financial stake in IMRT, the portion of patients referred for it roughly triples within about two years.”21

The consequences were predictable. First, the cost of treating prostate cancer patients skyrocketed. Second, many patients received IMRT who didn’t need it. In the words of urologist and researcher Matthew Cooperberg, who teaches at the Medical Center at the University of California, San Francisco, “IMRT is overused, period.”22 Cooperberg estimates that about 25,000 men with prostate cancer who receive IMRT each year either don’t need it or would fare just as well if given cheaper alternative therapies. “Doctors do what they’re paid to do,” he said. “If you tell them they can earn $2,000 for surgery or $37,000 for IMRT, what do you think will happen?”23 The financial cost? About $1 billion annually in overspending.24

WHAT’S MINE IS MINE, AND WHAT’S YOURS IS MINE TOO

Unfortunately, turf wars between competing specialty groups often muddy the evidence that doctors’ financial interests influence treatment recommendations. In 2012, Professor Mitchell published a study showing that urologists who offered laboratory services in-house billed Medicare for more prostate biopsies than urologists who did not, but detected fewer cases of cancer—a clear indication of overuse.25 How did urologists react? By accusing the competing professionals—pathologists and radiation oncologists—who helped fund Mitchell’s research of making “a money grab.”26 Dr. Deepak A. Kapoor, president of the Large Urology Group Practice Association, said that Mitchell’s study “simply furthers the political agenda of its sponsors to recapture lost market share and does not deserve credible recognition.”27 He also found it “offensive” to suggest that urologists “were performing extra and unnecessary pathology work for their own remuneration” and criticized the methodology Mitchell employed.28

It matters little whether, in this particular instance, Mitchell or Kapoor has the better argument. The point that incentives influence both the means by which medical treatments are delivered and physicians’ treatment recommendations is beyond dispute. When bringing ancillary services like IMRT and pathology labs in-house, urologists admitted that they were expanding their practices to make money. They wanted to replace revenues they lost when ADT stopped being a profit center. Nor is there any point in denying that physicians respond to economic incentives, just like other people, or in being ashamed of the fact that they do. Every business owner has to worry about revenue flows. Urologists run (health care) businesses, so they have to worry about revenues too. Better to admit that incentives matter and focus on getting them right than to pretend that they don’t.

Besides, urologists are hardly alone. After the MMA cut payments for chemotherapy agents, oncologists altered their practices too. They shifted away from drugs whose payments were reduced and switched to more profitable ones. They also gave drugs to more patients.29 Why? Because oncologists wanted to replace the income they lost. In the words of leading health care researcher and Harvard professor Joseph Newhouse, “hospitals and doctors will respond to changes in how they are paid.”30 That is not (or at least should not be) surprising—particularly when the “markups were a substantial portion of their income.”31

Having taken it on the chin when Congress passed the MMA, oncologists were loaded for bear when the U.S. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation recently announced its intention to experiment with a new way of compensating them for administering infusion drugs. Instead of paying the average sales price plus 6 percent—an arrangement that, as we discussed in Chapter 3, encourages providers to choose expensive medications over cheaper ones—it proposed a 2.5 percent bonus plus a flat payment of $16.80 per drug per day. Because the cost of infusing drugs doesn’t vary with their sales prices, the arrangement has intuitive appeal.

But the experiment, which had the potential to reduce Medicare’s drug-related payments by all of 0.7 percent, went nowhere—because oncologists teamed up with pharma companies and killed it. Paul Gileno, founder and president of the U.S. Pain Foundation, a not-for-profit organization funded by Pfizer and GlaxoSmithKline, said that the demo “would have severely undermined the quality and availability of care for patients suffering from cancer.”32 It is a curious objection, given that providers never complain when overpayments undermine the quality of care for cancer patients. And, of course, if the experiment had actually reduced the quality of care, the idea could have been scrapped. The real risk was that it might have proved that Medicare could pay oncologists less without endangering patients at all. Oncologists would not have liked that.

RENAL FAILURES

When it comes to gaming Medicare’s payment rules, kidney dialysis providers are among the worst offenders. Dialysis is big business. Medicare spends over $30 billion annually on treatments and medications for patients with end-stage renal disease. Until 2011, Medicare used a hybrid payment model that paid a flat rate for the basic dialysis service plus additional amounts for injectable medications and lab tests. The flat rate was known as “prospective payment” and the payments for medicines and tests were known as “separate billables.”

Dialysis companies couldn’t easily manipulate the prospective payment, but they did control the separate billables. This arrangement enabled them to inflate their revenues by pumping dialysis patients full of drugs and by using more expensive drugs (like erythropoietin) instead of cheaper ones to manage patients’ anemia. “Over time, separately billable services became the primary profit center for most dialysis units, and [erythropoietin became] Medicare’s largest drug expense.”33 Many patients suffered, because the high blood cell counts caused by excessive use of erythropoietin were associated with cardiovascular problems, including heart attacks and blood clots.34

One company, DaVita Health Care Partners, Inc., the country’s largest provider of dialysis services, was especially ingenious. It figured out how to make money by throwing medicines away. The scam was set out in a whistleblower complaint filed by Dr. Alon Vainer and Mr. Daniel Barbir, respectively, and formerly the medical director and a nurse at a Georgia dialysis center. The Department of Justice joined the case after it was filed.

The lawsuit focused on Venofer, an injectable drug that helps prevent iron deficiency anemia, and Zemplar, a vitamin D supplement. Until 2011, Medicare paid for these drugs on the basis of the amount dispensed. For example, if a pharmacist dispensed a 100 milligram (mg) vial of Venofer, Medicare might pay $30. Importantly, it paid $30 even if the provider injected only 25, 50, or 75 mg into the patient. The leftover portion was deemed to be unavoidable waste.

The whistleblowers charged that DaVita turned the drug payment system to its advantage by increasing the amounts of Venofer and Zemplar that it wasted. Venofer came in 100 mg vials, and the accepted treatment protocol was to give a dialysis patient an entire vial once or twice a month. This produced zero waste. DaVita didn’t do that. Instead, DaVita clinics gave 25 mg doses more frequently. But because the drug came only in 100 mg vials, each 25 mg dose of Venofer produced 75 mg of waste, which DaVita threw out. Then DaVita billed Medicare for the full average sales price of the 100 mg vial, plus 6 percent.35 In a two-month period, a DaVita clinic in Roswell, Georgia, allegedly threw out 19,750 mg of Venofer while administering only 9,625 mg to patients. Because Medicare paid DaVita on the basis of the number of vials that were used, the more medicine DaVita wasted, the more money it made.

DaVita tried to defend its practice of administering Venofer in small doses on medical grounds. Experts interviewed by a New York Times reporter were not persuaded. Dr. Michael Auerbach of Georgetown University said that “no clinical reason” and “no safety reason” justified giving Venofer in 25 mg increments.36 According to the reporter, “Dr. Daniel Coyne, a nephrologist at Washington University School of Medicine who treats some patients at DaVita clinics, said it was ‘absolutely true’ that the iron drug was given a bit at a time to make more money.”37 Dr. Coyne also asked rhetorically, “How could it be that patients in DaVita facilities were getting so much more iron than patients in other facilities and not getting iron overload?”38 “The answer,” he continued, “is the iron wasn’t going into them. It was being thrown away to make a profit.”39

The whistleblowers’ complaint also contended that DaVita stopped wasting drugs when Medicare changed payment approaches in 2011. Under the new rules, Medicare paid dialysis clinics a flat rate of $230 per treatment. No longer were injectable medicines billed separately. “For the dialysis centers, that instantly transformed the expensive drugs from a profit center to a drain on profits.”40 According to the whistleblowers, DaVita quickly switched its Venofer regimen from four 25 mg injections to one 100 mg injection, thereby reducing the number of vials dispensed and eliminating the waste. The change in injection protocols was “an instant case study of how financial incentives can influence treatment choices.”41

But DaVita did more than just eliminate waste. Drugs now hurt its bottom line, so it cut back on them and substituted cheaper medicines for more expensive ones. Other providers did the same. A study published in the American Journal of Kidney Diseases in 2013 found that erythropoietin use started to decline a few months before Medicare rolled out the new payment system and continued to fall throughout 2011.42 Vitamin D use also fell, and “there was a dramatic shift away from” a pricey drug to one that cost less.43 Finally, “the mix of iron products changed” again as clinics cut back on “expensive formulations.”44 These drug conservation measures saved providers so much money that their profits rose under Medicare’s new payment model, even though Medicare’s outlays fell.

Really, though, we didn’t need a peer-reviewed study to figure out that treatment practices changed radically. Epogen, manufactured by Amgen, is the most popular erythropoietin-stimulating agent. In the first quarter of 2011, “Amgen’s sales of Epogen, all of which are for use in dialysis in the United States, decreased 14 percent.”45 Dialysis patients no longer had to worry about getting too much erythropoietin.

Instead, they had to worry about getting too little. As “the average dosage of anti-anemia drugs taken by dialysis patients decreased by 18 percent from 2010 to 2011,” anemia occurred more often and more patients required blood transfusions.46 “[I]n each of the first nine months of 2011, the share of dialysis patients covered by Medicare who received blood transfusions increased by 9 to 22 percent over the corresponding months in 2010. . . . There had been virtually no change in transfusion rates between 2009 and 2010.”47 This was bad news for hopeful kidney transplant recipients. “[B]ecause transfusions . . . can change body chemistry and make it more difficult to find a compatible organ,” dialysis patients who receive them are “more likely to be among the 4,500 Americans who die each year while waiting for kidney transplants.”48

Once again, these findings indicate how important it is to design payment incentives properly, and to recognize that physicians and health care businesses can and will respond immediately and dramatically to the incentives that are created. Unfortunately, political control of health care spending makes it hard to get the incentives right. Providers who are overpaid (relative to the true market value of their services) will not volunteer that fact. Instead, they will lobby aggressively to maintain the excess payments. And, when the government pays too little, they will vigorously lobby for more, arguing that patients are unable to access needed care. Finally, when the government pays for the wrong thing or pays for the right thing in the wrong way, many providers will happily deliver the specified services and pocket the money. In our politically controlled system, it takes a long time for mistakes to be identified and corrected.

By contrast, when services are sold in competitive markets to patients who pay directly, providers are automatically encouraged to figure out what works best and deliver it. Markets reward providers who outperform their competitors by sending them more business. We discuss direct payment for medical treatments further in Chapter 17.

Nearly all health care providers whose scams are discovered deny having done anything wrong. DaVita was no exception. It defended against the whistleblowers’ lawsuit by claiming that Medicare approved its treatment protocol. But the house of cards began to fall in 2012, when DaVita settled a similar case involving Epogen in Texas for $55 million—while also proclaiming its innocence.49 Then, in 2013, DaVita reserved $300 million “to settle criminal and civil anti-kickback investigations by the Department of Justice,” which claimed, among other things, that DaVita paid nephrologists in the Denver area to refer patients to its facilities.50 The final collapse came in 2015, when the feds announced that DaVita would pay $450 million to resolve allegations that it sought to make money by intentionally wasting drugs.51

It may seem like providers—OB/GYNs, urologists, oncologists, and dialysis clinics—are the villains of this chapter. They are not. By pointing out that they respond to incentives, we are not suggesting that they differ from other people or businesses. The truth is that we admire health care providers enormously. One of us is a doctor and the other is married to a physician assistant. How could we not?

The real villains of this chapter are governmentally administered compensation arrangements that cause the interests of providers and patients to diverge. Once one recognizes that providers respond to incentives, one should immediately appreciate the importance of making it financially advantageous for providers to do what is best for patients. Compensation arrangements designed by regulators and elected officials only do that by accident, if ever. In every one of the examples discussed in this chapter, persons exercising governmental powers created compensation arrangements that rewarded providers for mistreating patients. The blame lies with them, or, more accurately, with the system that puts them in charge.

It is perfectly predictable that payment arrangements designed by government officials will cause the interests of providers and patients to conflict. Not only do these regulators lack the information needed to design compensation arrangements correctly, but their incentives are also defective. They neither gain when they design payment arrangements correctly nor lose when they incentivize providers to do harm. The combination of deficient information and defective incentives reminds us of the old gag, “What’s the difference between ignorance and apathy? I don’t know and I don’t care.”

Worse still, the project of aligning the interests of providers and patients is intrinsically hard. No compensation arrangement can motivate an agent to serve a principal well in all circumstances and, because technologies, knowledge, and other important factors change over time, an arrangement that works well today may perform poorly tomorrow. Markets deal with both problems by creating always-present incentives for sellers to take buyers’ interests to heart. Providers that serve patients well and adapt quickly to changes win customers and thrive. Those that serve patients poorly or seek to exploit them for financial reasons lose customers and fail. Markets do automatically what regulators don’t do at all.