CHAPTER 6: INTEGRITY

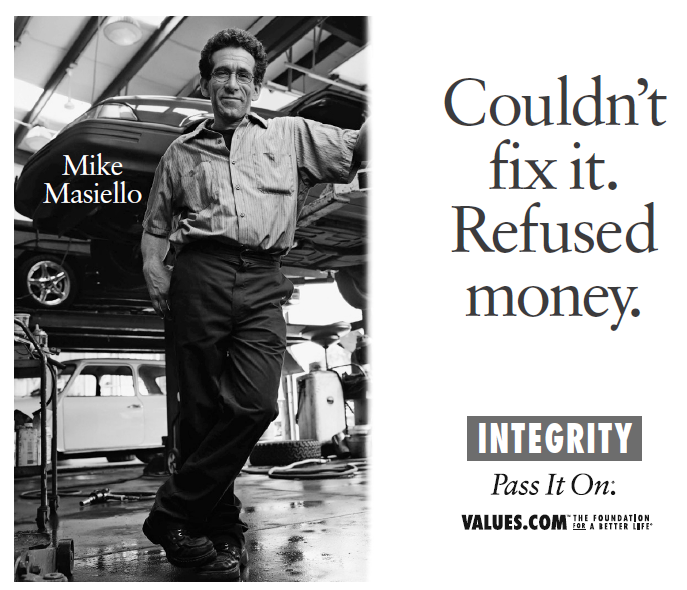

The Foundation for a Better Life creates public service ads supporting values like honesty, optimism, courage, and integrity. One of its billboards features Mike Masiello, a mechanic on Long Island. After spending almost three hours trying to fix a car, he realized the problem was unfixable. When the customer asked about the bill, Mike demurred, “I couldn’t fix it. I won’t take your money.”1

In the private sector, service providers who can’t solve customers’ problems often go unpaid. Trial lawyers are famous for this. They get paid only when they recover money for their injured clients. The payment arrangement they use is known as the contingency fee. It encourages them to choose clients with good cases and to do only things that are likely to make their clients’ claims more valuable. (Defendants complain that contingent-fee arrangements make plaintiffs’ lawyers too aggressive in service of their clients. But then again, plaintiffs’ lawyers don’t work for defendants.)

Health care providers don’t work on contingency. Every day, they get paid for treating illnesses they can’t fix. The most obvious example is “futile” care, which provides no benefit to patients. A recent study by critical care specialists at University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) found that 11 percent of the patients treated in their own intensive care unit “received aggressive treatment the doctors considered futile.” Another 8.6 percent “probably” received futile care.2 But UCLA doubtless billed and was paid for providing such care.

The difficulty of denying medical treatment to patients in critical condition must be obvious to any caring person. We do not mean to criticize doctors for being human. But treatments for intensive care unit patients who can’t be saved are the expensive tip of a much larger iceberg. Health care providers regularly dispense services that are unlikely to help patients and that may actually harm them. Some providers take this behavior to extremes, but these outliers are responsible for a small fraction of both the costs and the injuries that these treatments entail. The real problem is that the delivery of services of unproven value is business as usual in health care.

ANTIBIOTICS FOR ALL

Consider sore throats. There’s not much doctors can do about them. The vast majority don’t even warrant an office visit because the recommended treatment is rest and fluids. Only the few patients that have strep throat require antibiotics, and a quick test can show whether a given patient falls into that small group. Even so, 60 percent of the roughly 15 million Americans who go to the doctor every year with a sore throat come home with prescriptions for antibiotics, even though antibiotics have no effect on the viruses that cause most sore throats. What about acute bronchitis, also known as a chest cold? The national antibiotic prescribing rate for acute bronchitis should be close to zero because it too is usually viral, but it is actually 73 percent.3 Then there’s the flu. About half of all flu patients treated at outpatient clinics receive antibiotics even though the flu is viral too.4

Antibiotic overuse is as old as antibiotics. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has discouraged the unnecessary prescribing of antibiotics for decades. But the campaign to change doctors’ prescribing habits has failed so badly that some inappropriate prescriptions are now more common than ever before. Zithromax, which was introduced in the United States in 1991, is one example. During 1997–1998, it was hardly ever used for the treatment of adult patients with sore throats. By 2009–2010, doctors were doling it out to 15 percent of these patients.5

The volume of inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics is staggering. Every year, doctors prescribe more than 133 million courses of antibiotics to nonhospitalized patients. Depending on the source, between one-third and one-half of these prescriptions are unnecessary.6 That’s somewhere between 44.3 and 66.5 million useless prescriptions per year, counting only antibiotics.

One conservative estimate put the price at $500 million a year but noted that the actual cost could be 40 times as much, or $20 billion. The report added that 5 percent to 25 percent of patients given antibiotics experience diarrhea or other side effects, and many require follow-up treatments. Indeed, “[m]ore than 140,000 people, many of them young children, land in the emergency room each year with a serious reaction to an antibiotic. Nearly 9,000 of those patients have to be hospitalized.”7 Unnecessary prescriptions also contribute to the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.8

Antibiotic resistance, diarrhea, trips to the emergency room, hospitalizations, and somewhere between $500 million and $20 billion poured down the drain. That’s the tally of unnecessary waste and injury for just one type of medication. What explains this persistent problem?

The conventional wisdom is that patients want their doctors to do something, so doctors write prescriptions. As Shannon Brownlee wrote in Time magazine, “Most [doctors] do it out of habit or to make their patients happy. A mother brings her sick child to the pediatrician and expects to walk out with a prescription. It takes time for the doctor to explain why antibiotics won’t do any good and might in fact do her child harm.”9 If Brownlee’s right, doctors are contributing to antibiotic resistance, sending kids to emergency rooms, and wasting enormous amounts of money because it’s easier to hand out drugs than to deal with overly demanding moms.

Is that really the reason? There is another possibility. Doctors may prescribe antibiotics and other medications too often because insurers pay them extra when they prescribe drugs. In 2008, Medicare paid $63.73 for a low-complexity office visit (Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] code: 99213), but $96.01—almost 50 percent more—for a visit that involved “a new diagnosis with a prescription, an order for laboratory tests or X-rays, or a request for a specialty consult” (CPT code: 99214).10 The premium that private insurers paid was nearly the same.11 The incentive to dole out drugs should be apparent. If you’re thinking that the same incentive system could drive overuse of specialty consults, lab tests, and X-rays, you’re catching on. A 2008 medical journal article titled “10 Billing & Coding Tips to Boost Your Reimbursement” noted that just one additional 99214 code per day could net a physician “as much as $8,393 over the course of a year.”12

A big problem with the American health care system is that it pays providers well for doing things that don’t actually help patients. Dr. Rita F. Redberg, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and the chief editor of JAMA Internal Medicine—whom we met in Chapter 4—provides more examples, all drawn from Medicare:

- In 2009, Medicare shelled out more than $100 million for 550,000 screening colonoscopies. About 40 percent were for patients over 75, even though the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), an independent panel of experts financed by the Department of Health and Human Services, advised that these tests provided no net benefit.

- In 2008, Medicare spent more than $50 million on screenings for prostate cancer in men 75 and older and on screenings for cervical cancer in women 65 and older who had a previous normal Pap smear, again in the face of contrary recommendations by the USPSTF. Medicare spent millions more on unnecessary procedures that followed these tests.

- Two recent randomized trials found that patients who received two popular procedures for vertebral fractures, kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty, fared no better than those who received a sham procedure. Besides being ineffective, these procedures also exposed patients to considerable risks. “Nevertheless, Medicare pays for 100,000 of these procedures a year, at a cost of around $1 billion.”

- One-fifth of all implantable cardiac defibrillators are placed in patients who are unlikely to benefit from them. The cost to Medicare is $50,000 to $100,000 per implantation.

The total tally for unnecessary tests and procedures is staggering. Citing the chief actuary for Medicare, Redberg reported that Medicare’s 2010 budget could have been reduced by “$75 billion to $150 billion . . . without reducing needed services,” simply by withholding payments for things that don’t work.13

Redberg focused on studies of the Medicare program, but the problem of paying for things that don’t work extends well beyond medical treatments for seniors. Consider three examples supplied by Dr. David Newman.14

- Back surgeries to relieve pain are, in the majority of cases, no better than nonsurgical treatment. Yet doctors perform 600,000 of these surgeries each year, at a cost of over $20 billion.

- Despite studies showing that arthroscopic surgery to correct osteoarthritis of the knee is no better than sham surgery and is much more expensive and invasive than physical therapy, doctors perform the procedure on more than a half million Americans per year, at a cost of $3 billion.15

- Administering beta-blockers to heart attack patients “does not save lives, and occasionally causes dangerous heart failure.” Even so, “the medical community has continued to strongly recommend immediate beta-blocker treatment.”16

Dr. Newman thinks these practices persist, despite evidence of ineffectiveness, because elegant theories support them.17 He might have added that they also generate billions of dollars in revenue for health care providers. Many “comparative effectiveness” researchers think money is the primary driver. When trying to explain why providers keep delivering services shown to be ineffective or inferior, they observe, “Economic incentives, including the pervasiveness of both fee-for-service reimbursement and generous insurance coverage, are among the most commonly cited” causes.18

BIG MONEY FOR INEFFECTIVE TESTS AND TREATMENTS

Many big-ticket items could be added to these lists. Consider medical imaging. Radiologists perform more than 95 million high-tech scans each year, at a cost of more than $100 billion. One problem is that many scans, perhaps as many as half of them, are useless because their quality is poor. Health insurers pay for them anyway, because they don’t know whether the scans are good.19

A second problem is that doctors who purchase their own imaging equipment or own interests in imaging centers have incentives to order lots of unnecessary scans. “Studies have found that up to 3.2 times as many scans are ordered in such cases.”20 Self-referral is “tempting,” according to Dr. Bruce Hillman, a radiology professor at the University of Virginia, because “[i]t’s all profits.” A group of doctors “can reportedly make an extra $500,000 to $1 million a year simply by acquiring a scanner.”21

Other widely used treatments that don’t work, in the sense of either improving health or savings lives, are routine prostate-specific antigen (PSA) tests for prostate cancer in asymptomatic men and routine screening mammograms for breast cancer in healthy, middle-aged women. Start with PSA tests. Dr. Richard J. Ablin, the researcher who first isolated the prostate-specific antigen, coauthored a book, The Great Prostate Hoax: How Big Medicine Hijacked the PSA Test and Caused a Public Health Disaster, about the widespread and knowing misuse of PSA tests.22 He is palpably angry with the responsible members of the medical-industrial complex, many of whom he identifies by name.

Ablin’s basic point is straightforward and persuasive: PSA is a prostate-specific molecule, not a prostate cancer–specific molecule. In lay language, a PSA test shows only that some amount of a chemical produced by the prostate gland can be found in a sample of a patient’s blood. A high PSA score therefore provides an unreliable basis for diagnosing prostate cancer. Such an inference would be justified if the molecule was prostate cancer specific, but as Ablin explains it is not:

PSA levels are affected by a host of factors unrelated to cancer. For example, if a long-haul truck driver barreling over the Grand Tetons at night stops in a clinic the next morning to have a blood test, the jostling ride over the mountains could have elevated his PSA level. An amorous motel romp that evening could further elevate the level. So might [other relatively common conditions]. . . . The list of possible offenders goes on, but the outcome of PSA testing remains the same: the level is affected by numerous stimuli and the numbers do not necessarily indicate cancer.23

Even so, every year 30 million healthy men receive routine PSA tests as screens for cancer, a million men with high PSA scores are subjected to needle biopsies of the prostate gland, and more than 100,000 men undergo radical prostatectomies, “most of which are unnecessary.”24

For many men, the consequences of an elevated PSA test range from unpleasant to devastating. Eighty percent of the time, men with high PSA levels who get prostate biopsies turn out not to have cancer. The biopsies often cause pain, bleeding, and infections; some men die. All of these side effects stem from a test that is not very reliable in the first place.

What about the remaining 20 percent of the men with high PSA levels? They do have prostate cancer, but studies show that most of them would die from something else because most prostate tumors grow slowly. Dr. Peter B. Bach, of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, framed the matter this way: Suppose that, in 2009, a man had a positive PSA test followed by a biopsy revealing prostate cancer, for which he was treated. “There is a one in 50 chance that, in 2019 or later, he will be spared death from a cancer that would otherwise have killed him. And there is a 49 in 50 chance that he will have been treated unnecessarily for a cancer that was never a threat to his life.”25 As the saying goes, lots of men die with prostate cancer; relatively few die of prostate cancer. And treating prostate cancer has many potential serious side effects, including incontinence, erectile dysfunction, pain, bleeding, infection, and death.

Because PSA tests are not specific to prostate cancer, the results of several major studies are unsurprising. According to a review of the evidence conducted by researchers at the Oregon Health and Science University, “After about 10 years, PSA-based screening results in small or no reduction in prostate cancer-specific mortality and is associated with harms related to subsequent evaluation and treatments, some of which may be unnecessary.”26 PSA tests do discover some cancers serendipitously, and for that reason they do save some lives. But in return they exact a staggering toll in dollars and impairment of quality of life.

Why are so many men subjected to blood tests, biopsies, and surgeries they would be better off without? Money. We get what we pay for. We pay urologists for delivering PSA tests and performing surgeries, so we get both by the boatload irrespective of how often they actually benefit patients.

The analysis for mammograms is similar. Mammograms do detect breast cancers, but according to researchers at Dartmouth, only 3–13 percent of women whose breast cancers are found by mammograms are actually helped by the test.

Translated into real numbers, that means screening mammography helps 4,000 to 18,000 women each year. Although those numbers are not inconsequential, they represent just a small portion of the 230,000 women given a breast cancer diagnosis each year, and a fraction of the 39 million women who undergo mammograms each year in the United States.27

In other words, “of the 138,000 women found to have breast cancer each year as a result of mammography screening, 120,000 to 134,000 are not helped by the test.”28 That’s 87–97 percent. But many of these women have surgeries, radiation treatments, and chemotherapy, all of which are unpleasant, risky, and expensive. In an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2014, leading researchers wrote that a “review of 10 trials involving more than 600,000 women showed there was no evidence suggesting an effect of mammography screening on overall mortality.”29

Sometimes, doctors understandably think that they are helping patients by delivering treatments and prescribing drugs that later evidence suggests don’t work. They are naturally confused when early studies report promising results that later and more reliable studies contradict. This happens so often that an entire field of research, known as medical reversals, focuses on it. The most recent addition to this literature appeared in late 2017, when the Lancet published a randomized study that compared arthroscopic subacromial decompression—a common surgery for shoulder pain in which bone spurs and soft tissue are removed—with sham surgery (a placebo) and no treatment at all. The researchers found no clinically significant differences among the patients in the three groups. The invasive surgery was no better than the sham surgery, and neither procedure was significantly better than doing nothing at all.30

You might think that, when better studies show that treatments don’t work, doctors would stop recommending those treatments. The problem is that the early, less reliable studies spawn whole industries because doctors rush to perform services and prescribe medications that they expect to help patients. Years later, when better research reverses the initial study, shutting down the industry is hard because so many providers depend on it for their livelihoods.

Ablin discusses this in The Great Prostate Hoax. He quotes a Canadian physician who posits, “Without radical prostatectomies, more than half of all the urology practices in the United States would go belly-up.” Ablin agrees that financial considerations often account for inappropriate behavior: “many urologists defend PSA screening because without the test they would be pushed to the edges of irrelevance and . . . to bankruptcy.”31

Urologists are far from the only doctors in this position. Medical reversals have the potential to cut into other doctors’ practices too. In 2011, researchers at the Mayo Clinic found that almost half of the established medical practices they reviewed were no better than alternatives that were less expensive, simpler, or easier.32 In 2013, the same group produced a second report finding that 146 articles published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine from 2001 to 2010 reversed older studies, casting doubt on the effectiveness of 128 medical practices.33 But, because providers made money delivering them, the practices didn’t go away. In the words of Dr. Vinay Prasad, an oncologist with the National Cancer Institute and lead author of the report: “[W]hen we learn in certain cases that we were wrong, it’s much harder to stop doing something that we have been doing, especially when there’s money involved, and especially when the finances of the person making the recommendation are tied to the patient going through [with the recommended care].”34

BLAME INSURANCE

How did we get into this fix? By basing insurance payments for services on providers’ assessments of “medical necessity.”35 For much of the 20th century, doctors enjoyed great freedom to decide which treatments patients should receive. When they recommended treatments, patients went along. In effect, physicians controlled the level of demand for the services they supplied, constrained only by the state of medical science and patients’ ability to pay.36

The rise of third-party payment, including Medicare and Medicaid as well as private insurance, accelerated the pace of medical science and reduced patients’ incentive to scrutinize physicians’ recommendations. This disabled whatever brakes there were on health care spending. Predictably enough, demand went through the roof. Physicians made money and gained prestige by treating patients, so they gave their stamp of approval to many procedures of unproven efficacy. Writing late in the 20th century, professors Mark Hall and Gerard Anderson noted that “most current medical procedures were adopted without ever having been tested rigorously” and that “some of the procedures commonly used today have limited or no medical value.”37 In support, they cited a 1990 report by the Bipartisan Commission on Comprehensive Health Care, which found that “only 10–20% of the medical procedures used today have been subjected to randomized clinical trials—the most conclusive method of determining if a procedure is medically effective.”38 This is still true today. “Only a fraction of what physicians do is based on solid evidence from Grade-A randomized, controlled trials; the rest is based instead on weak or no evidence and on subjective judgment.”39

Clinical Evidence is a database that “showcase[es] the best available evidence on common clinical interventions” to support evidence-based medical decisionmaking. The folks who run it summarized what we know about 3,000 treatments in Figure 6-1.40 No one knows whether half of the procedures work or not. Another 8 percent are either unlikely to help patients or likely to harm them.

Figure 6-1. Effectiveness of 3,000 Treatments in Randomized Controlled Trials

Source: “What Conclusions Has Clinical Evidence Drawn about What Works, What Doesn’t Based on Randomized Controlled Trial Evidence?” BMJ Clinical Evidence, accessed Oct. 7, 2017, http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com/x/set/static/cms/efficacycategorisations.html.

Some untested treatments eventually prove to be helpful. But many turn out to be duds, and the duds generate billions of dollars in medical bills. PSA tests again provide an example. When the USPSTF recommended against regular PSA screenings in 2012, urologists protested and refused to abide by the new guidelines.41 Their reaction was predictable. PSA testing is a $30 billion industry.42 Threaten to shut down something that lucrative and providers will be angry.

PROVIDERS WON’T REGULATE THEMSELVES

Many professional associations know that their members deliver treatments that don’t work or whose efficacy is unproven. But, instead of providing solid leadership, they have dealt with the problem schizophrenically, indirectly enabling their members to keep doing whatever they want.

Consider how the cardiology profession dealt with the problem of excessive stenting, which we discussed in Chapter 4. In hope of curbing abuses, it promulgated appropriate use criteria (AUCs), which “are developed to determine whether a particular approach to care is reasonable in a given clinical scenario.”43 In 2009, a consortium of organizations published AUCs for cardiac revascularization procedures, including the insertion of stents. They sorted 180 possible treatment scenarios into three groups: appropriate, uncertain, and inappropriate.44 The last category was meant to capture all cases in which stenting was “not generally acceptable,” was “not a reasonable approach for the indication,” and was “unlikely to improve the patients’ health outcomes or survival.” A recent study found that uniform adherence to AUCs would save $2.3 billion.45 Inappropriate and uncertain stentings are that common and that costly.46

But when it came to requiring cardiologists to abide by AUCs, which many physicians derisively call “cookbook medicine,” the associations demurred. Pushback from practicing cardiologists led them to revise the AUCs, even to the point of renaming the categories. The category once called “uncertain” was rechristened “may be appropriate.” The “inappropriate” category is now “rarely appropriate.”47

Why the new labels? The official explanation was that the AUCs were never intended to prevent patients from receiving the medical treatments recommended by their physicians. The backstory was that, when procedures were classified as inappropriate, insurers balked at paying. “The term ‘inappropriate’ caused such a visceral response,” said Robert Hendel, a cardiologist at the University of Miami who reportedly pressed hard for the new terminologies. “A lot of regulators and payers were saying, ‘If it’s inappropriate, why should we pay for it, and why should it be done at all?’”48 Good questions.

Even under the original category names, the AUCs left a huge amount of room for cardiologists to exercise discretion. Many treatment scenarios fell into the uncertain/may-be-appropriate zone. When doctors recommended these treatments, insurers covered them even though, given the state of medical knowledge, it was impossible to be confident that implanting a stent would help a patient. But cardiologists wanted guaranteed payment for even more questionable procedures. They wanted insurance to cover all of their treatment recommendations, including those that would have been deemed inappropriate under the AUCs. This is the view that helped foster the epidemic of overstenting.

Isn’t a better question why payers should cover anything other than treatments that the evidence shows will improve health? According to the AUC classification scheme, interventions are “appropriate” when the science shows that “coronary revascularization would likely improve a patient’s health status (symptoms, function, or quality of life) or survival.” They are deemed “uncertain” when “more research, more patient information, or both [are] needed to further classify the indication.”49 In plain English, the label “uncertain” is chosen when the science doesn’t show that a procedure will help given a patient’s condition. But if there is too little evidence to conclude that a procedure will be beneficial, why should a cardiologist perform it? And why should Medicare, Medicaid, or a private insurer be expected to pay? Why not wait until we have enough information to be confident that the likelihood of helping a patient is strong?

IS A MEDICAL LICENSE A LICENSE TO EXPERIMENT?

The same question can be asked about many of the prescriptions that cardiologists hand out. Like other doctors, cardiologists often prescribe drugs for “off-label” uses that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) hasn’t approved or found to be effective. A drug named Vascepa provides an example. The FDA approved Vascepa as a treatment for patients whose triglyceride levels were off the charts. Knowing that Vascepa reduced triglyceride levels in these patients, cardiologists started prescribing it to many others, including those whose triglyceride levels were merely elevated. They did this despite the lack of “clinical evidence affirmatively demonstrating that lowering triglyceride levels [in the broader group of patients] . . . ultimately reduces cardiovascular risk.”50 No one knows whether Vascepa helped the thousands of people in the broader group who took it.

Physicians have prescribed drugs for off-label uses millions or even billions of times.51 No one knows how many of these prescriptions helped patients or how many harmed them. We know only that “‘off-label’ prescribing may place patients at risk of harm without adequate knowledge of the therapeutic risks and benefits.”52 Procedures that are classified as “uncertain” by AUCs do the same. No one can say whether they help patients or harm them because guesswork is all the science permits.

Although we are certain that most doctors who perform “uncertain” procedures or prescribe medications “off-label” have patients’ best interests at heart, the cold, hard, and uncomfortable truth is that they are experimenting on people. This is surely appropriate in some situations, such as when a patient has a life-threatening illness and all approved treatments have failed. But in less dire circumstances, the calculus is more complicated. Do we really want to encourage doctors to experiment without the benefit of patients’ informed consent, approved research protocols, rigorous data collection methods, control groups, and oversight by institutional review boards?

In fairness, many off-label uses are well established and apparently helpful, clinical trials are expensive and time consuming, and some experiments turn out well for patients. (We discuss ophthalmologists’ inventive off-label use of a cancer drug to treat wet macular degeneration in Chapter 3.) The answer is not clear-cut. Our point is just that the payment system provides a clear and unambiguous signal, encouraging any and all off-label uses.

Not surprisingly, these massive experiments often fail. Time and again, clinical research has shown that commonly prescribed procedures and drugs either confer no benefits on patients or actually harm them. Consider a recent example. Since the late 1960s, cardiologists and other doctors have implanted filters in patients who are at risk of suffering from blood clots in their veins. The filters are supposed to keep clots from reaching the lungs, where they often prove fatal. But no study showed that the filters benefited patients who are also receiving anticoagulants—medicines that prevent clots from forming. And the filters have known side effects. Finally, in 2015, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a randomized, controlled study of the issue. It found that the filters “conferred no benefit whatsoever” over anticoagulant medication alone.53

The result wasn’t altogether surprising. In 2013, the authors of a study of variation in treatment practices across hospitals observed that, although 50,000 patients received filters each year, “there [was] no evidence that inserting a [filter] improved survival.”54 Taking note of this fact, three doctors who commented on the 2013 study wondered, “How Could a Medical Device Be So Well Accepted Without Any Evidence of Efficacy?”55

We offer three reasons. First, doctors had a theory suggesting that the filters should work. Second, once the practice of using filters gained a following, doctors simply “assumed that there was strong evidence for their use.”56 Why else would so many doctors have put so many filters in so many patients? Third, Medicare, Medicaid, and other payers covered the procedures. In hospital settings, Medicare paid $3,300 for filter insertion, $2,600 for filter repositioning, and $2,600 for filter removal. When these procedures were performed in a doctor’s office, the fees were $2,800, $1,800, and $1,750, respectively.57 Treatment patterns got well ahead of the science. When the science finally caught up, there was a large financial incentive not to reverse course.

AUCs and other professional guidelines are pointless unless they limit practitioners’ discretion and prevent them from recommending aggressive treatments too often. The tendency to overprescribe reflects a confluence of factors: physicians’ strong desire to help, their belief in the efficacy of their tools, and, of course, the strong financial incentive to perform procedures. As Dr. Redberg put it when discussing the epidemic of overstenting, “It’s like asking a barber if you need a haircut. To an interventional cardiologist, stents are good for almost everyone.”58

THE POLITICS OF WASTE

Many doctors still offer their male patients routine PSA tests, including elderly patients for whom the tests are a complete waste of time.59 Insurers still pay for the tests too. They’re reluctant to cut back on benefits because they risk being caught in a political firestorm when they do. Government agencies run the same risk. Consequently, many are loath to recommend against unnecessary medical services.

Consider the fate that befell the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) when it issued recommendations discouraging the use of surgery for the treatment of lower back pain. AHCPR convened a panel of experts who, after conducting a comprehensive review of the clinical literature, concluded that there was no evidence that surgery should be the first-line treatment for lower back pain.60 They also concluded that there was no evidence that spinal-fusion surgery was superior to other surgical procedures but that it did lead “to more complications, longer hospital stays and higher hospital charges than other types of back surgery.”61 Acting on these findings would have required orthopedic surgeons to curtail these treatments, thereby reducing their income.

Instead of complying, disgruntled surgeons joined forces with congressional critics of the Clinton health plan and attacked the AHCPR.62 The agency ultimately survived, but Congress dramatically reduced its budget, rescinded its authority to issue treatment guidelines, and gave the agency a new name: the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The AHCPR issued those findings in 1994. Since then, little has changed. “[T]here are still no rigorous, independently funded clinical trials showing that back surgery is superior to less invasive treatments,” but orthopedic surgeons keep on operating and insurers keep on paying, even for spinal fusions. In fact, the number of those procedures has grown, “from about 100,000 in 1997 to 303,000 in 2006.”63

Nor have the politics of waste changed. Fifteen years after the brouhaha surrounding the AHCPR, the USPSTF was overwhelmed when it recommended that healthy women in their 40s should not have routine annual mammograms.64 The guideline reflected the USPSTF’s assessment of the evidence that, for normal women in this age group, the expected health benefits of frequent mammograms are so small and the expected health costs are so large that the procedure would probably do more harm than good. The balance tilted negative because mammograms generated false positive findings, which caused women to undergo unnecessary treatments for tumors that posed no risk to their health. Financial costs did not enter the picture—federal law prohibits the USPSTF from considering the dollars that might be saved by reducing the frequency of mammograms. Had financial considerations been taken into account, the USPSTF’s conclusion would have been even stronger.

Congress deliberately attempted to insulate the USPSTF from politics, so its members can focus solely on whatever the evidence says. But because the USPSTF had not consulted the relevant interest groups, its members were unprepared for the firestorm its recommendation against mammograms unleashed. No sooner were the new guidelines announced than trade associations accused the USPSTF of trying to save a few bucks by putting women’s health at risk. “Leaders of the American College of Radiology and the Society of Breast Imaging issued statements . . . that the new recommendations looked like an effort to cut costs.”65 Prominent doctors piled on. Time magazine quoted Dr. David Dershaw, the director of breast imaging at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, as saying that he was “appalled and horrified. There is no doubt that mammography screening in women in their 40s saves lives. To recommend that women abandon that is absolutely horrifying to me.”66

Patient advocacy groups followed the industry’s lead. When the American Cancer Society announced its rejection of the new treatment recommendation, Dr. Otis Brawley, its chief medical officer, took advantage of the public’s ignorance and stood its logic on its head. “With its new recommendations, the [USPSTF] is essentially telling women that mammography at age 40 to 49 saves lives; just not enough of them.”67 As it happens, that’s exactly right: the procedure does not save enough lives to make up for the damage it inflicts. Brawley just left out the second part.

As always, politicians tried to use the uproar to their advantage. The recommendation came in the midst of a debate over whether to enact health care reform. Republicans used the issue to accuse Democrats of wanting to ration care. Representative Marsha Blackburn’s (R-TN) comments were typical: “This is how rationing begins. This is the little toe in the edge of the water. This is when you start getting a bureaucrat between you and your physician. This is what we have warned about.”68 Then-representative Candice Miller (R-MI) called the recommendation “‘a huge step backward’ that puts the nation on a ‘slippery slope’ to discouraging screening for other diseases based on cost rather than medical need.”69 Then-representative Michele Bachmann (R-MN) played the gender card and stoked unspecified fears: “Women . . . may lose a great deal of clout in decision making. . . . We don’t know how far government will go in this bureaucracy.”70 Bachmann would later run for president.

A few Democrats tried to defend the recommendations,71 but President Obama’s Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius was not one of them. Instead of backing the USPSTF, she pointed out that President George W. Bush had appointed its members. Then she disavowed the new guideline, expressing her personal opinion that women in their 40s should have annual mammograms. She also asserted that annual mammograms would still be covered by private and public insurance, no matter what the Task Force said.72 As far as we know, Sebelius had no training in medicine, statistics, or anything else relevant to the issue in question. But, she had been a politician, and she knew which way the wind was blowing.

The following year, Sebelius confirmed that, under Obamacare, annual mammograms would be covered—for free. The new insurance plans in which people enroll, she wrote, “will be required to cover recommended preventive services without charging you a copayment or deductible. This includes annual screening mammograms for women starting at age 40.”73 Free is in the eye of the beholder, of course. Mammograms run about $200 apiece, and the total cost of screening the cohort of women in their 40s has been pegged at $2.24 billion.74 Someone’s going to pay, just not patients at the point of service. They’ll get millions of mammograms that are more likely to harm them than help them. But at least they’ll be “free.”

The decision to require coverage of mammograms for women in their 40s actually ran counter to a provision of Obamacare. The law requires Medicare and private health insurance plans to bear the entire cost of preventive services to which the USPSTF assigned a grade of A or B, both of which meant that the USPSTF “recommends the service.”75 But the USPSTF came out against diagnostic mammograms.76 So why did Obamacare cover them?

Because Congress overrode that part of the law. When the controversy erupted, members of both parties worried that women would blame the USPSTF’s decision on them. So they amended Obamacare by grandfathering in the old 2002 guideline, which favored annual breast cancer screenings for women in their 40s.77 Republicans abandoned their commitment to reduce federal spending the instant an opportunity arose to shower money on an important voting bloc. Democrats abandoned their commitment to letting science guide policy. Both parties’ actions bring to mind Groucho Marx’s famous quip: “These are my principles. If you don’t like them . . . well, I have others.”

The mammogram debacle made it clear that we can’t (and shouldn’t) trust Congress to control health care spending. It taught the USPSTF a lesson too. When the parties submitted their proposals to undo its 2009 ruling, the GOP’s bill included a provision stripping the USPSTF of its power to make binding recommendations. Having endured that brush with death after being attacked from all sides, the USPSTF will presumably avoid controversy going forward. We can’t expect it to stem the growth of health care spending either.

What about Obamacare? Although Obamacare put some money into outcomes research, it explicitly focused the responsible entity (the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, or “PCORI”) on comparative effectiveness research—that is, whether different treatments work better than each other—not cost-effectiveness research, a more rigorous way of evaluating medical tests and treatments. And the law significantly constrains the ability of the federal government to use the results of PCORI’s work to make coverage or reimbursement decisions. Professor Nick Bagley, who believes that Obamacare’s statutory language actually provides PCORI with a lot of flexibility, nevertheless acknowledges that “it would be foolish—maybe suicidal—for the institute to dwell on cost concerns.”78 If PCORI decides to disregard Bagley’s assessment, we expect the result will be déjà vu all over again.

WHY DO PRIVATE INSURERS KEEP PAYING FOR TREATMENTS THAT DON’T WORK?

If we can’t depend on the federal government to keep doctors from wasting money and hurting patients, what about private insurers? Won’t they leap at the opportunity to save a buck by denying coverage for things that are shown not to work?

Unfortunately, in many cases, the answer appears to be “no.” First, private insurers typically get paid a small percentage of the amount of money they pay out. The more money they pay out, the more money they make. When private insurers cut back on the stream of payments, they lower their own take. Just like everyone else in the health care system, their incentives point in the wrong direction. Second, the last time insurers did try to step up to the plate (in response to pressure from employers), they got their heads handed to them. During the 1990s, private insurers tried to use managed care to clamp down on the provision of unnecessary services by requiring pre-approval for some treatments, limiting the facilities at which doctors could provide certain procedures, and denying coverage for extended hospitalizations. The resulting “managed care backlash” was real—and it made it clear to insurers that there would be real costs in trying to reduce health care providers’ revenue streams.

Consider how private insurers handled the problem of percutaneous vertebroplasty. This procedure, which we mentioned briefly above, involves injecting bone cement into the spine to treat vertebral fractures. Medicare first covered the procedure in 2001, and most private insurers followed suit. In 2009, the New England Journal of Medicine published two randomized double-blind studies that compared it with a sham procedure that involved inserting needles into the spine without actually injecting the bone cement. Both studies showed no evidence that vertebroplasty performed any better than the sham procedure. Even so, private insurers continued to cover the procedure and physicians continue to perform it at will.79 Even compelling new information indicating that a procedure is worthless cannot spur private insurers to act.

There’s a TV commercial where the comedian Beck Bennett asks a group of school kids “Who thinks more is better than less?” All the kids raise their hands. That’s what most Americans think about health care. But more is often worse. More can injure. More can kill. And more always costs more money. The AHCPR tried to tell us. Private insurance companies tried to tell us. The USPSTF tried to tell us. But we didn’t want to listen, because it’s all someone else’s money anyway. And health care providers don’t want any of it to stop coming to them. It’s best for them if we think like the school kids: more is better . . . more is better . . . more is better. . . .