CHAPTER 8: PAYMENT-INDUCED EPIDEMICS

SECONDARY CONDITIONS OF PRIMARY INTEREST

Most epidemics are caused by infectious diseases such as influenza, malaria, HIV, dengue fever, or Ebola. But America’s politicized third-party payment system has also caused a few. Acute heart failure, which involves a dangerous and often deadly breakdown in the heart’s ability to pump blood, is one of them. From 2008 through 2010, Chino Valley Medical Center (CVMC) in San Bernardino County, California, claimed that 35.2 percent of its Medicare patients suffered from acute heart failure as a secondary condition to other problems for which they were hospitalized.1 This seems to have been untrue. Rather, CVMC appears to have created a seeming epidemic by inflating its billings.

In a 2011 exposé, investigative journalists from California Watch discovered that CVMC had “billed Medicare for the costs of confronting what appear[ed] to be a cardiac crisis of unprecedented dimension.” CVMC’s patients were experiencing acute heart failure at a rate that was six times the statewide average. The epidemic hit CVMC’s Medicare patients with septicemia (a life-threatening blood infection) particularly hard; almost 8 percent of the Medicare patients treated by CVMC had both septicemia and acute heart failure—more than 15 times the statewide average.2

Was there really an epidemic of heart failure among elderly patients in San Bernardino County? If so, it is hard to explain why other hospitals in the area missed it. They too had cardiac care units, but they didn’t experience a similar rise in heart failure cases. Either CVMC was a statistical anomaly or something else was going on.

Given what California Watch found, that “something else” appears to have been “upcoding”—an industry term meaning that CVMC was manipulating patients’ records to trigger larger payments from Medicare and other insurers. Medicare pays more for treating patients with major complications. By making patients seem sicker than they were, CVMC was able to game Medicare’s payment system and reap substantially larger payments.

Medicare pays a fixed amount for the hospitalization of a patient with a particular illness. To make things concrete, let’s say the fee is $5,500 for a hospitalized patient with Legionnaires’ disease. If the patient also has a secondary condition, like acute heart failure, Medicare pays more, because the patient requires additional services. In the case of our imaginary patient with Legionnaires’ disease, adding acute heart failure as a secondary condition might trigger a bonus payment of almost $6,000 more—bringing the total payment up to $11,400.

Upcoding is possible because Medicare doesn’t know whether a given patient has acute heart failure as a secondary condition. Medicare doesn’t even know whether a patient has the coded primary condition. As Medicare’s failed experiment with prepayment review (discussed in Chapter 7) demonstrates, Congress doesn’t much care, either. Medicare relies on hospitals to bill honestly. Unfortunately, many hospitals take advantage and boost their revenues and profits by making up secondary conditions that don’t exist.

That certainly seems to be what CVMC did. CVMC didn’t report a single acute heart failure case as a secondary condition in 2006, before bonus payments were available. By contrast, after bonus payments were introduced in 2007, California Watch found that CVMC treated “1,971 Medicare patients for acute heart failure” between 2008 and 2010, and “in 88 percent of the cases, [acute heart failure] was listed as a secondary diagnosis that typically would trigger bonus payments.”3

California Watch interviewed two heart specialists who said they found CVMC’s heart failure rate implausible. Dr. Gregg Fonarow, the director of the Ahmanson–UCLA Cardiomyopathy Center and the associate chief of the Department of Cardiology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, stated, “You don’t see (hospitals) where 35 percent of the Medicare population has heart failure.” Dr. Steven Shayani, a cardiologist and president of the New York Heart Research Foundation, observed that CVMC’s acute heart failure complication rate “doesn’t make any sense” and wondered why Medicare officials weren’t investigating.4 Both experts suspected that doctors or billing personnel at CVMC were exaggerating patients’ illnesses.

PRIME’S NUMBERS

CVMC was owned by Prime Health Care Services, which operates a chain of hospitals, including 13 in Southern California. In a shocking coincidence, of the 10 California hospitals with the highest reported rates of acute heart failure, Prime owned 8. Prime’s hospitals also reported unusually high rates of other dire and rare conditions. One of these was kwashiorkor, an extreme form of malnutrition most often experienced by starving children in sub-Saharan countries that are stricken by droughts or embroiled in civil wars.5 The kwashiorkor secondary diagnosis entitled Prime to $6,000 extra per patient. At one Prime hospital in Shasta County, California, fully 16 percent of Medicare patients were suffering from kwashiorkor—70 times the statewide average. Overall, Prime reported that 25 percent of its Medicare patients were malnourished, compared to a statewide average of 7.5 percent. In another shocking coincidence, of the 10 California hospitals with the highest reported rates of malnutrition, Prime owned 8.

Here’s another way to look at the same numbers. Prime hospitals treated 3.6 percent of Medicare patients in California, but they accounted for 12 percent of the state’s malnutrition cases and 36 percent of its kwashiorkor cases. If Prime’s billing figures were right, the elderly population in California was extremely malnourished.6 The mystery, again, was why other hospitals missed the epidemic. Their Medicare bills rarely mentioned kwashiorkor. Either Prime’s doctors were unusually adept at spotting sub-Saharan malnutrition or something else was happening.

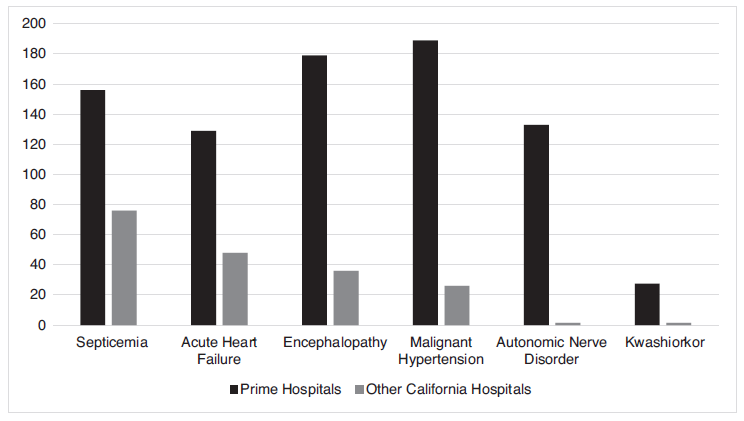

Figure 8-1. Incidence of Listed Illnesses per 1,000 Medicare Patients at California Hospitals (2009–2010)

Source: Adapted from California Watch, “Prime Healthcare Reports Outsized Rates of Unusual Conditions,” December 16, 2011, http://static.apps.cironline.org/primehealth-care/.

Prime’s billing records indicated it was also experiencing epidemics of other diseases that its competitors were failing to treat. Figure 8-1 shows how illness rates reported at Prime’s hospitals differed from those at other California hospitals, as reported by California Watch. If Prime’s bills were right, medical personnel at other hospitals were systematically failing to detect serious illnesses.

Did real illnesses explain these extraordinary differences, or was Prime systematically defrauding Medicare? One important piece of evidence: the kwashiorkor epidemic at Prime ended right after California Watch published its story.7 At the Prime hospital in Shasta County, the rate of kwashiorkor plummeted overnight, from 16 percent of admitted Medicare beneficiaries to zero. Similar results were observed at other Prime hospitals. Either the media can work miracle cures or Prime stopped billing for kwashiorkor as a phony secondary condition the minute it got caught.

UPCODING EMERGENCY CARE

If Prime hospitals were upcoding, they weren’t alone. After Medicare implemented bonus payments for secondary conditions in 2007, “63 other hospitals that had reported no [cases of ] acute heart failure in 2006 also began recording cases of the ailment.”8 Prime hospitals even had company in other states when it came to reporting elevated frequencies of kwashiorkor. In 2012, the Good Samaritan Hospital of Maryland settled claims that, from 2005 to 2008, it inflated its Medicaid bills by falsely reporting that its patients suffered from this ailment. Two Catholic hospitals, Christus St. Vincent Regional Medical Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Mercy Medical Center in Des Moines, Iowa, “each billed Medicare for more than 100 cases of kwashiorkor between 2010 and 2011.” All of these diagnoses were found to be unwarranted. (The hospitals blamed faulty billing software.) “All told, the federal health care program paid more than $700 million in 2010 and 2011 for patients diagnosed with kwashiorkor.”9

There’s more to the upcoding story than phony secondary conditions, however. The Center for Public Integrity (CPI) published a series of “Cracking the Codes” investigative news reports in which it found widespread overcharging by hospitals for treatments delivered to Medicare patients.10 For example, the bills submitted by the Baylor Medical Center in Irving, Texas, indicated that its patients were “among the sickest in the country.” “In 2008, the hospital billed Medicare for the two most expensive levels of care for eight of every 10 patients it treated and released from its emergency room—almost twice the national average. . . . Among those claims, 64 percent of the total were for the most expensive level of care.”11 According to CPI’s published account, a Baylor spokesperson conceded that the hospitals’ bills for emergency room (ER) treatments were out of line with industry standards.

That may not have been true. Upcoding is so widespread that it may be the industry standard. Studying the first decade of the 21st century, CPI found that hospitals added more than $1 billion to the cost of Medicare by using the most remunerative billing codes more often. “Use of the top two most expensive codes for emergency room care nationwide nearly doubled, from 25 percent to 45 percent of all claims, during the time period examined.”12 In many instances, the patients for whom these codes were used were not seriously ill. “Often, they were treated for seemingly minor injuries and complaints” and sent home without being admitted to the hospital.13

How did hospitals account for the increase in the severity of illness reported? By claiming that sicker patients were coming to their ERs. Dr. Stephen Pitts, an emergency physician and associate professor in the Emory University School of Medicine who examined data on ER visits, dismissed this explanation. “It’s total nonsense,” according to Dr. Pitts.14

The CPI attributed the billing surge to “lax government oversight, confusion about proper billing standards, and widespread payment errors that have plagued Medicare for more than a decade. And the data suggest that some hospitals are working the billing system—and its flaws—to maximize payments.” Dr. Donald Berwick, a former Medicare administrator, agreed, saying, “They are learning how to play the game.” Barbara Vandegrift, a health care consultant, was even blunter: “It’s ‘wait until we get caught and we’ll fight it at that point.’”15 This attitude makes sense because the risk of being caught is small. Medicare lets hospitals establish their own billing policies, offers little guidance, and rarely audits.

PAYMENT-INDUCED CURES

The payment system doesn’t just cause epidemics. It sometimes cures them too. The most famous example involves pneumonia, a respiratory infection that can be deadly. Between 2003 and 2009, the medical establishment seemed to have pneumonia on the ropes. Hospitalizations for pneumonia dropped by 27 percent and the death rate fell by a third. The reason for these stunning improvements was not entirely clear. Doctors were treating pneumonia the same way they had been for years.

Most people know better than to look a gift horse in the mouth. Why question a victory in the endless war against infectious diseases? But academic researchers were curious, so they looked into hospitals’ coding practices. Their findings, which appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association, showed that credit for the victory belonged to the payment system, not to hospitals or physicians.16 Although admissions with a primary diagnosis of pneumonia fell from 2003 to 2009, hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of sepsis and a secondary diagnosis of pneumonia rose by an almost equal amount. The rate at which patients with pneumonia were hospitalized hadn’t declined at all. The reduction in death rates was phony as well. Patients whose primary diagnosis was pneumonia were dying less often, but when researchers combined those patients with the patients who had pneumonia coded as a secondary diagnosis, they found that the death rate hadn’t budged. Pneumonia was just as common and as deadly as always. Public health officials were using billing records to track infection rates—and they were deceived by a change in the billing practices of hospitals. The triumph over pneumonia was a paper victory, not a real one.

Why had hospitals changed their coding? The lead author of the study observed that “there’s a strong financial incentive for coding based on sepsis versus pneumonia” because hospitals get paid more for doing so. There was also a national campaign to raise awareness about sepsis. The combination made it easy for providers to change their coding practices.17

The payment system also created a false victory over avoidable hospital readmissions, which are thought to occur when hospitals provide shoddy care, release patients too soon, or provide inadequate services postdischarge. Wanting to encourage hospitals to do better, Medicare began a “pay-for-performance” initiative that included financial penalties for hospitals that readmitted too many patients within 30 days of discharging them. The initiative, known as the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), seemed to be successful. Readmission rates fell by about 70,000 cases the year it took effect.

In fact, the quality of care delivered by hospitals had not improved. They reduced their readmission rates by gaming the payment system. Instead of admitting patients who appeared to be at risk for premature readmission, they put them on observational status or treated them in their emergency rooms. When these patients later returned for additional treatments, they could be admitted without causing problems because they had not been formally admitted the first time around. Hospitals also used these tactics to avoid readmitting patients who returned within 30 days of being discharged. They’d put these patients on observational status or treat them in ERs too, so they wouldn’t count as readmissions either. More than two-thirds of the decline in readmissions had nothing to do with quality of care and everything to do with gaming the payment system.18

Not only did the HRRP not cause hospitals to treat patients better, the initiative may have actually cost thousands of patients their lives, according to a study published in JAMA Cardiology in 2017. Since heart failure (HF) is “the leading cause of readmissions among Medicare beneficiaries,” researchers decided to study the relationship between the HRRP and mortality in patients with HF. They found that as the HRRP drove down the 30-day and 1-year readmission rates for HF patients, the 30-day and 1-year mortality rates for these patients increased.19 Dr. Gregg Fonarow, one of the researchers involved in the study, estimated that “10,000 patients a year with heart failure [were] losing their lives as a consequence of [the HRRP], an absolutely devastating level of potential harm.”20 Wanting to avoid the financial penalties they stood to incur by readmitting patients too often, hospitals and doctors were treating HF patients in ways that shortened their lives.

TURBOCHARGED BILLING AND OUTLIER PAYMENTS

Few people associate hospitals with greed. Most consider them “good guy” community organizations that differ fundamentally from other businesses of similar size. The fact that many are nonprofit organizations adds to the halo effect. But the truth is that hospitals are big businesses and are run as such. Like the other businesses that operate in the health care sector, they are adept at taking patients and their insurers (both public and private) to the cleaners.

Consider the amounts that hospitals charge for their services. These figures are found on “chargemasters”—lists of charges (i.e., prices) that all hospitals maintain. At one point, these charges may have been closely related to hospitals’ actual costs, but over time they took on a life of their own. A study published in Health Affairs found that chargemaster prices are, on average, 3.4 times the actual cost of patient care. At the 50 greediest hospitals, charges are more than 10 times actual costs.21 Into the 1980s, Medicare paid hospitals on a cost-plus basis, so hospitals profited by inf lating their costs. Medicare no longer uses that arrangement, but hospitals still gain by exaggerating.

One reason is that they have learned how to use inflated chargemasters to extract additional dollars from insurers and patients. These effects were quantified in a 2017 study by Michael Batty, an economist at the Federal Reserve Board, and Benedic Ippolito, a researcher at the American Enterprise Institute. Combining national data on hospitals’ list prices with data from California on payments, they found that “an additional dollar in the price set by the hospital chargemaster was associated with an extra 15 cents in payments from a commercially-insured patient.”22 The effect on uninsured patients was larger: a 20-cent increase in payments for every extra list-price dollar. The researchers also learned that the effect on uninsured patients disappeared after 2007, when California’s Hospital Fair Pricing Act kicked in. The act allows hospitals to charge uninsured patients only as much as Medicare pays. (Although this section focuses on prices, it is worth noting that Batty and Ippolito found no correlation between hospitals’ chargemaster prices and the quality of care they delivered, as measured by 30-day readmission rates. Pricier hospitals weren’t better than cheaper ones.)

It is easy to see how inflated chargemaster prices enable hospitals to extract extra dollars from uninsured patients. Many uninsured patients pay all or part of their bills, and the amounts they pay correlate with what they are charged. Charge them more, and they pay more. It is as simple as that.

When it comes to obtaining payments from insurers, the role of chargemasters is both less obvious and more complex. One possibility is that hospitals set their list prices high so as to be able to bargain down from them in negotiations with insurers, stopping when the discounts are just large enough to get insurers to agree. This “flea market“ strategy helps hospitals price-discriminate, just as drug companies do (see chapters 1–3), and it is consistent with the fact that hospitals’ negotiated prices are industry secrets. By negotiating different discounts from their list prices for different payers, hospitals can charge each payer the most it is willing to pay—that’s price discrimination. But the strategy works only if the discounts that hospitals are willing to accept remain hidden. Otherwise, all insurers will know how low hospitals are willing to go.

Another theory offered by Batty and Ippolito is that hospitals use high list prices to gain leverage over insurers. They do this in a surprising way: by exposing patients to high out-of-network charges unless their insurers include them in their networks. Suppose that a city has two hospitals—Hospital A and Hospital B—but only Hospital A is in a patient’s insurance network. If the patient is involved in an accident or the patient’s doctor has admitting privileges only at Hospital B, there is a risk that the patient will have to be treated there and will be balance billed for the out-of-network charge. Wanting to eliminate that risk, the patient may go looking for a new insurer that has both Hospital A and Hospital B in its network. And the higher Hospital B’s list prices are, the more the patient will want to avoid the risk by finding a new insurer. The desire to retain subscribers will therefore exert pressure on insurers to strike deals with all major providers in their areas, enhancing the providers’ leverage in price negotiations.

Even though Medicare no longer pays on a cost-plus basis in most situations, high chargemaster prices still help hospitals extract dollars from it too. When an elderly patient’s treatment ends up costing a hospital a lot more than Medicare normally pays, hospitals can claim extra “outlier” payments. And, when determining whether an outlier payment is warranted and how large it should be, Medicare uses chargemaster prices as proxies for hospitals’ costs. Once again, political control of the payment system lets providers set the prices they receive from Medicare. By inflating their chargemaster prices, hospitals can increase both the likelihood of receiving outlier payments and the amounts they are paid.

The practice of using chargemasters to obtain outlier payments by inflating costs is known as “turbocharging.” Many hospital companies have played this game. Tenet Health Care Corporation (discussed in Chapter 4) allegedly collected more than $1 billion in outlier payments by inflating its prices to an average of 477 percent of costs. Tenet’s outlier payments went from $351 million in fiscal year 2000 to $763 million in fiscal year 2002.23 At most hospitals, outlier payments generated 4–5 percent of Medicare revenue, but at Tenet they accounted for 23.5 percent of Medicare revenue in 2003. Eventually, Tenet was forced to clean house and modify its chargemaster. When it did so, its outlier payments plummeted. Tenet ultimately paid more than $900 million for misconduct involving turbocharging, upcoding, and paying kickbacks to physicians. It also paid another $10 million to resolve securities fraud claims relating to turbocharging.24

Beth Israel Medical Center (BIMC) also got caught turbocharging and admitted guilt as part of a $13 million settlement.25 BIMC inflated its charges by 200 percent between 1996 and 2003, even though its costs for treating Medicare patients grew by only 10 percent. In dollar terms, from 1996 to 2003, BIMC’s Medicare inpatient costs increased by only $17.4 million, while its Medicare inpatient charges increased by more than $285 million.26

Usually, wrongdoers refuse to confess culpability when settling with the feds. Why did BIMC choose to come clean? We suspect that the feds insisted on a confession because the evidence was so damning. There were many memoranda and emails in which hospital executives embraced the turbocharging strategy. For example, in 2000, a vice president for patient financial services at the company that owned BIMC wrote that the hospital would “keep the charges high even at the lowest levels of service in the E.R.”27 Another executive wrote of “feeling a bit giddy” at the thought of “getting $10 million of outlier revenue.” A third advised caution because she feared that BIMC’s turbocharging would be detected.

The Lenox Hill Hospital, which gained considerable fame when Beyoncé went there to deliver her daughter, also pled guilty to turbocharging. It “admitted, acknowledged, and accepted responsibility for having increased its charges based on revenue models that did not directly take into account the costs of the services provided, and as a result obtaining Medicare outlier payments it would not otherwise have received.”28 Federal prosecutors claimed that from February 2002 through August 2003, Lenox Hill intentionally raised its room and board charges and manipulated its overall charge structure to make it appear as though its treatment of certain patients was unusually costly, when in fact it was not. The settlement required Lenox Hill to pay $11.75 million. Beyoncé and Jay-Z, who spent an estimated $1.3 million on their maternity suite and delivery, may not have known about Lenox Hill’s deliberately inflated chargemaster prices, or they may have negotiated themselves a better deal. We should not assume the same for Lenox Hill’s other patients.

Medicare changed its payment rules in 2003 to make it harder for hospitals to game the system. It subsequently discovered that hundreds of hospitals had turbocharged. How many did so without being caught, we will never know. Turbocharging has also resurfaced in the last few years. A Wall Street Journal article published in 2015 gave four examples:

- Somerset Medical Center in New Jersey had an increase in outlier payments in 2010 and 2011 six times higher than each of the five previous years. The payments in 2010 and 2011 together totaled $13.6 million. About $10.5 million of those payments were due to increased list prices.

- Christ Hospital in New Jersey collected $2.93 million in 2013 in special payments from Medicare, a 60 percent markup over 2012.

- Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, one of the largest recipients of Medicare outlier payments in the country, had an increase in outlier payments of about $18 million due to list price increases in the 2013 fiscal year.

- Health Management Associates Inc. raised the list prices of a hospital chain it acquired in Florida in 2011. Medicare payments for outlier claims jumped from $150,000 to $6.2 million, of which $5.2 million was found to be due solely to list price increases. 29

Continued turbocharging led Tom Scully, the former head of the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) who implemented the change in payment rules in 2003, to remark that “efforts to curb excess payments are ‘like Whac-a-Mole.’”30 That’s such a good analogy that we chose it as the title for our chapter on policing health care fraud (Chapter 12).

OVERBILLING ELECTRONICALLY

The latest upcoding scams involve electronic health records (EHRs). The federal government tried to get providers to use EHRs for decades, claiming that they would improve quality and save money. Providers finally got on board when the federal government offered them $30 billion in bribes.31

The main thing EHRs appear to have improved was providers’ ability to commit fraud. First, the EHR program itself was hit by providers who wanted to be paid for adopting EHRs, even though they had not. According to the Dallas Morning News, a chain of six small-town hospitals in Texas run by Dr. Tariq Mahmood received almost $16 million in bonus payments for implementing EHRs.32 To get the money, the hospitals had to certify that they met various measures of “meaningful use” of electronic records. However, instead of actually using EHRs, the hospitals kept paper records and hired an outside vendor to manually input data into electronic form after patients were discharged. So much for “meaningful use.”

Second, EHRs make providers much more efficient upcoders. Merely by clicking a button or a menu or copying information from one patient’s records to another’s, a provider can enter a condition, treatment, or other factor that triggers a high payment.

In 2012, the New York Times reported, “the move to electronic health records may be contributing to billions of dollars in higher costs for Medicare, private insurers and patients by making it easier for hospitals and physicians to bill more for their services, whether or not they provide additional care.”33 At Faxton St. Luke’s Health care in Utica, New York, the fraction of patients treated in the emergency room who were supposedly treated at the highest level of service intensity (thereby triggering higher payments) rose by 43 percent in 2009, the year the hospital switched from paper records to EHRs. At the Baptist Hospital in Nashville, the portion of emergency patients who were supposedly treated at the highest level of service climbed 82 percent in 2010. This was the year Baptist switched to EHRs too. And at Methodist Medical Center of Illinois in Peoria, “billings for the highest level of emergency care jumped from 50 percent of its emergency room Medicare claims in 2006 to more than 80 percent in 2010, making the 353-bed hospital one of the country’s most frequent users of high-paying evaluation codes.”34

The perversity of subsidizing EHR adoption becomes even clearer when one compares hospitals that received subsidies with hospitals that didn’t get the cash: “Over all, hospitals that received government incentives to adopt electronic records showed a 47 percent rise in Medicare payments at higher levels from 2006 to 2010 . . . compared with a 32 percent rise in hospitals that have not received any government incentives.”35 In 2010, 54 percent of emergency room claims were in the two highest-paying categories, up from 40 percent in 2006.36 Congress literally paid hospitals to find ways to charge taxpayers more.

Multiple peer-reviewed studies and governmental reports show that upcoding and other forms of gaming are pervasive.37 According to Dr. Donald W. Simborg, who chaired a federal panel on EHR fraud, “It’s like doping and bicycling. Everybody knows it’s going on.”38 In 2012, Kathleen Sebelius, secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and Eric Holder, the attorney general, sent the American Hospital Association and other industry groups a sternly worded letter urging them to discourage hospitals from using EHRs to game the system.39 They might as well have asked scorpions not to sting frogs.40

ROBIN HOOD, M.D.

Doctors are surprisingly open about their willingness to game the payment system. In 2000, Dr. Matthew Wynia, the director of the AMA’s Institute for Ethics, and coauthors published a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association reporting that 39 percent of physicians admitted to deceiving insurers within the previous year.41 In 2002, Medical Economics asked doctors, “Have you ever exaggerated or misstated a patient’s diagnosis to a third-party in order to secure authorization for a treatment, procedure, or hospital stay that might otherwise have been denied?” Twenty-one percent answered “Yes.”42 Internists reported fudging diagnoses more often than other specialties; 32 percent admitted using this tactic. Almost a decade later, another journal published a study finding “strong evidence” that the possibility of obtaining larger payments by charging for more intensive services than were actually delivered “influences physician’s coding choice[s] for billing purposes across a variety of specialties.”43 “For general office visits,” the study reported, “Medicare outlays attributable to upcoding may sum to as much as 15% of total expenditures for such visits.”44

Physicians’ openness about their willingness to commit fraud reflects a variety of beliefs that make it easy for them to rationalize cheating. First, many doctors believe that public and private insurers shortchange them routinely. Insurers pay too little, refuse to cover important services, and often deny coverage entirely for reasons that doctors find arbitrary and unfathomable. Second, physicians believe they are ethically obligated to help their patients. Deceiving insurers helps both doctors (who get paid) and patients (who get the services they need). In a society where TV shows like ER, Scrubs, and Grey’s Anatomy portray doctors who defraud insurance companies as heroes saving patients from evil corporations, it’s easy to rationalize gaming.

Consider the case of former gynecologist Neils H. Lauersen, whom Geraldo Rivera dubbed the “dyno gyno.” Lauersen “was convicted in 2001 of billing insurance companies for gynecological operations when he was really giving fertility treatment for women he said could not afford it.”45 Gynecological procedures were covered by insurance. At the time, fertility treatments were not. So, Lauersen used codes for the former when performing the latter, manufacturing insurance coverage out of thin air.

Lauersen treated C. C. Dyer, then Geraldo Rivera’s wife, who subsequently bore two children. She thought him a hero. “To me, he was Robin Hood, taking from the big bad companies and giving to the poor just trying to have a baby,” Dyer said.46 Lauersen was no Robin Hood. He lined his pockets by deceiving insurers. In his criminal trial, he was accused of collecting $5 million by intentionally miscoding procedures.47 His prodigious billings helped him maintain a fancy Park Avenue office and move about in the loftiest of social, artistic, and political circles.

Dozens of Lauersen’s patients attended his trial and insisted, like Dyer, that he was a hero. A contemporaneous profile gives a sense of the arguments that were offered at trial:

Although his defense hinges on the line that Lauersen did not perform infertility treatments at the expense of unwitting insurance companies, there’s a steady undercurrent to it that says, So what if he did? “The government’s calling me Robin Hood, robbing from insurers and giving to my patients,” Lauersen says, smiling at the characterization. “Insurance companies should be paying for these women.”48

The first trial ended with a hung jury. Press reports indicated that “one juror in particular said later that she simply did not believe insurance companies.”49 Then, New York’s medical licensing board concluded that Lauersen was a danger to his patients and suspended his license to practice medicine. Court records indicated he had been sued 26 times, more than 6 times the lifetime average for OB/GYNs. Lauersen was then retried on the fraud charges, convicted, sentenced to seven years in prison, and ordered to pay $3.2 million in restitution.

Lauersen’s actions were illegal. Even so, many people regard what he did as either desirable or, at worst, a petty offense. People hate insurers. A large segment of the public thinks they are greedy, bloodsucking parasites, and that insurance fraud is necessary to even the score.50 Many of Lauersen’s patients belonged to that group. They were happy to have their health care carriers pay for fertility-related services that their policies didn’t cover, and for which they had never paid. Doctors find it easy to rationalize insurance fraud too. When asked about upcoding, they often shrug off the suggestion that suspect billing patterns indicate fraud and claim instead that their patients are unusually sick.

Thousands of self-declared, white-coated Robin Hoods are bleeding the federal treasury dry. According to a 2012 Office of the Inspector General report, 5,000 physicians “consistently billed for high level” codes when applying for payments from Medicare.51 They get away with it partly because upcoding is easy. If a doctor selects one code when treating a new patient, Medicare will generate a check for about $37. If the doctor chooses a different code instead, Medicare will pay $190. Slight changes in billing codes can trigger bigger payments from private insurers too.52 Payers’ ability to monitor the accuracy of doctors’ bills is limited, so as a practical matter, doctors can pick the codes they want. Not surprisingly, thousands pick the codes that generate the highest payments. With about one billion visits to doctors’ offices a year, the aggregate financial impact of these small retail-level instances of cheating is staggering.

BILLING FROM THE GRAVE

Upcoding is probably the most common form of overbilling, but there are many other types. Dr. Farid Fata, a Michigan oncologist, provided a recent and truly stomach-turning example of a different technique.

Fata told healthy patients that they had cancer so he could make money by giving them chemotherapy they didn’t need. Fata reportedly “gave one of his patients 155 chemo treatments over two-and-a-half years—even though the patient was cancer-free.”53 He is said to have pumped other patients full of unnecessary blood therapies and iron treatments. Even though Dr. Fata was busy ripping off Medicare and his patients, a Detroit magazine named him one of the “Top Docs” in 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2011, and 2012. In 2015, he was found guilty and sentenced to 45 years in prison after abusing the trust of more than 550 patients and receiving more than $17 million through fraudulent billings.54 He dreamed of living out his life in a $3 million castle in Lebanon, but he is now, fortunately, rotting away in jail.55 Dr. Fata may not be seeing patients anymore, but the Detroit magazine still has him listed on their website as a “Top Doctor.”

When we read about Fata’s misdeeds, we initially thought he was unique. We now know better. Dr. Salomon Melgen, whose story is discussed in Chapter 7, falsely diagnosed patients as suffering from wet age-related macular degeneration, then charged Medicare for treating them. Dr. David Ming Pon, who was sentenced to 10 years in prison, performed laser surgery on hundreds of patients whom he falsely diagnosed as having glaucoma. He too was convicted of Medicare fraud.56 With three such cases having popped up in a short span of years, we are forced to wonder how many more monsters are out there who have so far avoided discovery.

Other doctors make up claims out of whole cloth. In 2014, federal prosecutors charged Syed Imran Ahmed with submitting more than $85 million in Medicare claims for services he never delivered.57 The feds also sought to seize his ritzy Long Island home, worth approximately $4 million. But they were too late to get all the loot. Ahmed wired $2 million out of the country immediately after being interviewed by the FBI.58 Amazingly, Ahmed is thought to have committed the fraud over a period of just two short years—proof that a corrupt doctor can bleed the system of large sums quickly.

The feds win most Medicare fraud prosecutions, so Ahmed’s conviction came as no surprise.59 Still, most doctors who overbill are never even arrested, let alone tried. Many mix a limited number of fraudulent claims in with a larger volume of legitimate ones, making their fraud essentially invisible. Fata, the overmedicator, was a notorious overbiller, but his misdeeds were discovered after a nurse who once worked at his clinic turned him in. Despite the heinousness of his offenses, it still took the feds three years to arrest him after receiving the whistleblower’s report.60

Fata and Ahmed can be punished because they’re alive. But how are the feds supposed to deal with doctors who submit phony bills after they die? In 2007, Congress received a report showing that upward of 18,000 dead doctors had filed over 478,500 claims with Medicare. The report also revealed that Medicare had shelled out as much as $92 million to pay claims from dead doctors.61 In 16 percent of the cases, the departed doctors had been dead for more than 10 years. But Medicare just kept on paying. Medicare opened for business in 1965, but almost 45 years later it still had “no reliable way to spot claims linked to dead doctors.”62 In 2009, 2,500 doctors who died before 2003 still had active identification numbers. In a model of understatement, Sen. Norm Coleman (R-MN) remarked, “When Medicare is paying claims and the doctor has been dead for 10 or 15 years, you know there is a serious problem.”63

And, because every type of billing fraud that can occur does, there are also live doctors who bill for treating dead patients. One famous case involved Dr. Robert Williams, a Georgia physician. From 2007 to 2009, he submitted more than 50,000 claims to Medicare and more than 40,000 claims to Medicaid for group psychology sessions, many of which supposedly involved nursing home residents who were dead or hospitalized when the sessions were said to have occurred.64 Medicall Physicians Group Ltd. ran a similar scam. In mid-2015, a Chicago jury convicted two people associated with Medicall of billing Medicare for physician services that were never delivered, including services that were supposedly rendered to patients who were dead, that were delivered by providers who were no longer employed by Medicall, or that were provided by professionals so industrious they worked more than 24 hours a day.65

How big a problem is this? No one knows. An Office of the Inspector General investigation found that, in a two-year period, Medicare “recovered $3 million in improper payments stemming from approximately 27,000 claims for services billed for deceased beneficiaries.”66 If CMS recovered that much, it undoubtedly paid out much more. But no one is keeping track.

REWARDING THE GUILTY, PUNISHING THE INNOCENT

CMS has tried to offset its losses from upcoding and other types of overpayment by reducing payments to providers in general. It did this in 1984 and 1985, when it cut hospital payments by 3.38 percent and 1.05 percent, respectively. It wanted to go after hospitals again in 2008, 2009, and 2010, but each time Congress intervened and prevented it from doing so. Upcoding also led CMS to whack payments to home health agencies by 2.75 percent each year from 2008 to 2010 and by 2.71 percent in 2011. Payments to inpatient rehabilitation facilities and long-term acute care hospitals have also been cut to offset this form of fraud.

Imposing across-the-board cuts rather than dealing with upcoding directly is counterproductive. It tempts honest providers to upcode. Otherwise, they get punished and lose money while the bad guys continue doing it. It therefore makes upcoding seem legitimate, reduces the stigma that normally accompanies illegal behavior, and destroys the norm of billing honestly.

It may help to see this point from another angle. When CMS reduces all providers’ payments because of upcoding by some, it sends a clear signal that it can’t tell the honest providers from the frauds. This means that it’s smarter to upcode than to bill accurately because the odds of being singled out for punishment are small. It also makes providers who bill honestly look and feel like chumps. A government program that makes it more profitable to deceive regulators than to submit truthful bills is a program that sows the seeds of its own destruction, because it fosters attitudes and beliefs incompatible with the rule of law.

How much does all this upcoding cost? It’s impossible to be sure, but a report from the HHS Office of the Inspector General found that, in just one year (2010), Medicare paid $6.7 billion too much for evaluation and management (E&M) services, a category that includes visits to doctors’ offices, emergency room assessments, and inpatient hospital evaluations. To put the dollar figure in context, $6.7 billion was 21 percent of the total amount that Medicare paid for E&M that year.67

ProPublica’s study of Medicare spending data provides another look at the scope of the problem.68 Using a five-level system with a score of 5 corresponding to the most expensive level of care, the watchdog group found that in 2012, 1,200 doctors and other health professionals billed at level 5 exclusively, while 600 more did so more than 90 percent of the time. Some 20,000 providers billed only at levels 4 and 5. Apparently, they never saw patients who required less complicated care, even though such patients appeared in other doctors’ offices all the time. Of the more than 200 million office visits that Medicare paid for in 2012, only 4 percent commanded the most expensive rates—indicating something is almost certainly seriously awry with the billing practices of the 20,000 providers who billed only at levels 4 and 5.

How did the physicians who consistently used the most expensive codes explain their actions? When questioned by ProPublica, “[s]ome doctors . . . said that their patients were sicker than those of their peers and required more time and attention.”69 The Reverse Lake Wobegon Effect rears its ugly head again. Anyone want to bet on whether this is real or just another payment-induced epidemic?