CHAPTER 9: OUT OF NETWORK, OUT OF LUCK

SURPRISE! HERE’S YOUR BILL

McAllen, Texas, has attracted a lot of unwelcome attention. In 2009, surgeon and medical writer Atul Gawande pegged it as the highest-cost county in the United States for Medicare, with per-patient spending almost twice the national average. It was a mystery why spending there was so high. McAllen’s population was similar to El Paso’s, another border town in the same state, but Medicare’s per-patient spending in El Paso was average.1 Doctors and hospitals in McAllen simply delivered more services than providers anywhere else.

McAllen is America’s capital of surprise medical bills too. These are bills that patients receive after being treated at hospitals that are in their insurance networks from physicians who are not in-network. According to a 2017 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, 89 percent of the patients who were treated in emergency rooms at in-network McAllen hospitals received bills from doctors who didn’t take their insurance.

These problems are not limited to McAllen. Complaints to the Texas Department of Insurance about surprise bills rose by 1,000 percent from 2012 to 2015.2 Concern was so widespread that, in 2017, Texas enacted a new law that entitles patients to demand mediation for out-of-network bills.3 The law doesn’t do much, but given Texas’ pro-business slant, the legislation of any protection at all for consumers is remarkable.

The problem of surprise bills is nationwide. A Consumers Union survey found that about one-third of privately insured respondents had received an unanticipated bill within the preceding two years.4 A survey conducted jointly by the Kaiser Family Foundation and the New York Times reported that, “among insured, non-elderly adults struggling with medical bill problems, charges from out-of-network providers were a contributing factor about one-third of the time.”5 According to a New England Journal of Medicine study, 22 percent of patients received a bill they did not expect.6 A study in the health policy journal Health Affairs found that “20 percent of hospital inpatient admissions that originated in the emergency department, 14 percent of outpatient visits to the [emergency room, or ER], and 9 percent of elective inpatient admissions likely led to a surprise medical bill.”7 Another study of nine million ER visits from 2011 to 2015 found 22 percent of patients who went to an in-network hospital received a bill from an out-of-network ER physician.8

Surprise bills hit patients from many directions. They come from anesthesiologists, radiologists, surgical assistants, lab technicians, and other providers who, despite delivering services at hospitals that are in patients’ insurance networks, are not in those networks themselves. In one reported instance, two parents were billed over $4,000 in out-of-network charges because, although the hospital where their infant son was born was in-network, its neonatal intensive care unit was not.9

When providers are out-of-network, they can bill patients at their own vastly inflated chargemaster prices instead of the discounted rates that insurers pay. If you’ve seen a bill from an in-network provider or the corresponding “explanation of benefits” from your insurer, you know what we mean. The hospital or physician may “charge” a chargemaster price of, say, $3,000 for a service. But the insurer will disallow a huge chunk of that—say, 75 percent. The real price is $750. The insurer will pay all, some, or none of that price, depending on the health plan’s cost-sharing structure.

But, when a surprise bill from an out-of-network doctor comes in, it will demand $3,000 without the discount. The insurer then pays the same amount it would otherwise—that is, no more than $750. The patient is then on the hook for the rest—anywhere from $2,250 to $3,000. This is known as “balance billing.” The patient is responsible for the difference because the doctor, being out of network, never agreed to accept the insurer’s discounted rate.

Balance billing for out-of-network treatment is a scam. In almost every instance, the provider who is demanding the full rack rate routinely accepts far less as payment in full from in-network patients and from patients who are covered by Medicare or Medicaid. Those are the provider’s real prices. As we discussed in the previous chapter, the rack rate or chargemaster price is simply a number pulled out of thin air to help providers extract as much as they can from each patient. Those numbers bear no relationship to providers’ costs, either. On average, hospitals charge out-of-network patients 3.4 times, and the 50 worst offenders charge more than 10 times, the actual cost of the services they use.10

Hospitals are hardly alone in gouging patients. Aetna once sued an out-of-network New Jersey physician who treated a patient at an in-network hospital. Aetna claimed that the doctor charged $31,939 for services whose reasonable value was only $2,811, which Aetna paid. In a fit of generosity, the doctor then “balance billed” the patient just $10,635, rather than the entire $29,128 balance, a fact that itself indicates how inflated out-of-network rack rates can be.11 Other doctors’ rack rates are just as phony. According to a report published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2017, anesthesiologists, radiologists, and ER doctors regularly charge out-of-network patients four to six times more than they accept from Medicare for the same services.12 Anesthesiologists were the worst offenders.

Balance bills are thought to average about $900, but providers often demand far more.13 Peter Drier was told he had to have neck surgery. He researched his insurance coverage and thought he knew what to expect. But after the operation, he received a $117,000 surprise bill from an “assistant surgeon” he hadn’t known about or met.14 The bill was “20 to 40 times the usual local rate” and orders of magnitude larger than the $6,200 fee charged by the primary surgeon. Patricia Kaufman, who had surgery at a Long Island hospital for a chronic neurological condition, was victimized too. Two plastic surgeons charged more than $250,000 to sew up her incision, “a task done by a resident during [her] previous operations.”15 After Kaufman’s insurer paid about $10,000, the surgeons balance billed her for the rest. John Elfrank-Dana, a 58-year-old father of three who worked as a public school teacher in New York City, needed a series of procedures after slipping on some steps and banging his head. His surprise bills tallied $106,000.16 The list of examples of crippling surprise bills is endless—and they can wreak havoc with patients’ finances, particularly if the provider sends the bill to a collection agency.

Rural residents, accident victims, and other persons who need to be airlifted to hospitals face especially great risks. Air ambulance services can charge whatever they want, so patients who use them can wind up on the hook for truly enormous sums.17 Consider a representative example:

When Amy Thomson’s newborn daughter was in heart failure, Ms. Thomson had to use an air ambulance service in rural Montana for transport to a more capable facility. At the time, her insurance company, PacificSource, did not have an in-network air ambulance company near her family . . . . Ms. Thomson received a $43,000 balance bill from Airlift Northwest after PacificSource contributed a policy cap of $13,000.18

WHOSE FAULT IS IT?

When one asks providers why balance billing occurs so often, they blame insurers. Rebecca Parker, the president of the American College of Emergency Physicians, provides a perfect example. When asked why ER doctors send out so many surprise bills, she replied: “This is insurance company bad behavior.”19 That seems like an odd thing to say, given that doctors, not insurers, send out the bills. But Dr. Steven Stack, who served as president of the American Medical Association, agrees. “The real crux of the problem,” he says, “is that health insurers are refusing to pay fair market rates for the care provided.”20 Hospital administrators agree that insurers are the guilty parties, and should “pay more, expand their networks, and eliminate the problem.”21 If providers are right, the problem isn’t that they’re greedy. It’s that insurers are cheap.

Naturally, insurers see things the other way around. They accuse doctors who balance bill for out-of-network charges of price gouging, and they accuse hospitals of being complicit. They contend that it is hospitals’ “responsibility to ensure all physicians treating patients in their facility are covered by the same insurance contracts as the hospital.”22 Some insurers are steering people away from hospitals that refuse to do just that. Aetna encouraged its subscribers to avoid Allegheny Health Network hospitals in Pittsburgh when ER physicians there began to balance bill aggressively. UnitedHealthcare went one better—or one worse, depending on one’s perspective. It announced that it would no longer cover any medical bills for members who unknowingly received out-of-network treatment by physicians at in-network hospitals.23 The execs at UnitedHealthcare must have figured that administrators at in-network hospitals would be careful to assign only in-network doctors to patients if they knew that any contact with an out-of-network physician would eliminate insurance coverage for all of the bills.

Because all this finger-pointing leaves patients exposed, lawmakers have launched themselves into the breach. New York adopted a comprehensive approach that lets patients off the hook for out-of-network charges when they seek emergency medical treatments or are cared for at in-network hospitals. In these situations, providers have to accept insurers’ in-network rates, but can use arbitration to try and get more. Altogether, about half the states have enacted laws that protect patients who need emergency medical treatments from surprise bills. But patients who receive scheduled procedures are still vulnerable. This is one reason why many health policy experts think federal regulation is necessary.24

The unanswered question is why so much surprise billing occurs. It isn’t a problem in other contexts where people pay for things with insurance. If your car is damaged in an accident, the body shop will send you and your insurer a single, all-inclusive bill. You won’t be charged a separate fee over and above what your insurer pays by the technician who does the paint job or the mechanic who replaces your dented fender. Body shops pay the workers whose services are required and bill for everything themselves. Market forces have pressured them to bundle services and charges into packages that are convenient for consumers and to accept compensation at rates that insurers and consumers are willing to pay.

Nothing prevents hospitals from doing what body shops do. They too could bring all service providers in-house and submit all-inclusive bills to patients and insurers. Then there would be no surprise bills. Hospitals could also allow doctors to remain independent but require them to have agreements with the same insurers the hospitals do, as a condition for treating patients. In fact, some hospitals do this.25 Patients treated at these hospitals don’t have to worry about being balance billed.

But many hospitals seem to go out of their way to create opportunities for surprise bills. Some have no doctors in their ERs who are in the same insurance networks they are. Literally every patient admitted to these hospitals’ ERs is likely to end up being balance billed. The same fate awaits patients who undergo surgery at hospitals with no in-network anesthesiologists. After having her thumb operated on, Elaine Hightower was balance billed for $6,300. Her hospital and doctor were in-network but the anesthesiologist on duty that day wasn’t.26 Often, patients meet their anesthesiologists for the first time shortly before being wheeled into surgery. Those with the temerity to ask them whether they are in-network may discover the anesthesiologists themselves do not know. Then, the patient faces the Hobson’s choice of risking a hefty out-of-network bill, or undergoing a procedure without anesthesia.27 This is no way to run a railroad, let alone a hospital.

Why have some hospitals solved the problem of balance billing while others have not? And why are surprise bills from ER doctors, anesthesiologists, and a few others especially common?

TO MAKE OR TO BUY—THAT IS THE QUESTION

Anesthesiologists, radiologists, pathologists, and other doctors who send out lots of surprise bills tend to be independent contractors. They deliver services at hospitals, but they are not hospital employees. Their status differs from that of the many other doctors who are employees, a group that includes staff physicians of many types. In recent years, the number of staff physicians has exploded, as hospitals have brought on board thousands of doctors who formerly practiced independently. Over a three-year period ending in 2015, “Hospitals acquired 31,000 physician practices, a 50 percent increase.”28 The number of hospital-employed doctors now exceeds 140,000. By and large, these doctors don’t balance bill because they are full-time employees. If the hospital is in-network, they are too.

Why did hospitals bring so many more doctors under their umbrellas while farming out their ERs to independent contractors and leaving other doctors, like anesthesiologists, radiologists, and pathologists, independent?

To understand the answer, it helps to know some basic economics. For a business, the decision to produce a good or service internally or to obtain it from an external supplier is known as a “make or buy” decision. Neither option is intrinsically better. When a business can profit more by making something itself than by buying it from someone else, it will choose the former option and acquire the resources needed to produce it. When it is more profitable to purchase a good or service from an external supplier, it will do that instead.

Today, for example, most businesses find it more economical to buy electric power from a utility than to generate it themselves. When deciding whether to “make or buy” electricity, they opt for the latter. As solar panels become cheaper and more efficient, though, the calculus is changing and some businesses are going off the grid. Some homeowners are doing so too. A transition from “buying” electric power from an external supplier to “making” it is underway because the costs and benefits of producing power are changing.

By bringing certain doctors in-house, hospitals are acting like other businesses that decide to make some services internally rather than buy them from an external source. Hospitals are trying to maximize their profits, which they think they can do by having some doctors become employees. By leaving other doctors outside, hospitals are implicitly saying that they are better off having customers separately buy the services those doctors provide. The same financial considerations that drive commercial firms to “make or buy” certain services also drive hospitals to make the same decisions.

How do hospitals profit by turning some (but not all) independent physicians into employees? When you look at the physicians who become hospital employees, two things stand out. First, many of these doctors provide services that generate payments known as “site-of-service differentials” that make it advantageous for hospitals to hire them. Second, many of these physicians refer patients to hospitals for profitable treatments. Some do both. The doctors that hospitals do not hire are those who offer neither site-of-service differentials nor patient referrals.

A MIGRATION OF WILDEBEESTS

Here’s how site-of-service differentials affect hospital executives’ thinking. Patients can receive medical treatments at different locations. For example, they can get colonoscopies in doctors’ offices or at hospitals’ outpatient departments, among other places. You might think that Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers would pay the same amount for colonoscopies regardless of where they take place (also known as “site-neutral payment”). But you’d be very wrong. Payments vary considerably by location, and hospital-provided colonoscopies generate a lot more revenue.

In 2012, Medicare paid an average of $1,300 for colonoscopies performed in doctors’ offices, but it shelled out $1,805—39 percent more—when these procedures were delivered at hospitals.29 That is why only 4 percent of all colonoscopies were performed in doctors’ offices that year.30 By performing them in hospitals, doctors and hospitals were able to split the extra money. Because it is financially advantageous for hospitals to bring gastroenterologists (and other doctors who perform lots of colonoscopies) onto their staffs, colonoscopies don’t generate lots of balance bills. (This is true for gastroenterologists’ services. Anesthesia delivered in connection with colonoscopies may be a different story.)

The same was true for cardiologists. Consider an example discussed by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, or MedPAC, which studies and advises Congress on how to improve the government’s payment systems. When a cardiologist in private practice provided a level II echocardiogram without contrast, Medicare paid $188. But, when a doctor connected to a hospital performed the same test in an outpatient context, the payment was $452.89.31 That’s an additional $265 that the hospital and doctor can share—including an additional $212 from taxpayers and $53 from the patient—to their mutual advantage. As Mark E. Miller, MedPAC’s Executive Director, told Congress, site-of-service differentials like this one “giv[e] hospitals an incentive to acquire physician practices and bill for the same services at outpatient rates, increasing costs to [Medicare] and to the beneficiary.”32

The incentive to “make” cardiac services in-house grew in 2009, when Medicare reduced payments to cardiologists with independent practices while raising payments to hospitals when staff cardiologists performed the same tests. Since then, the New York Times reports, “the number of cardiologists in private practice has plummeted as more and more doctors sold their practices to nearby hospitals that weren’t subject to the new cuts.” After one cardiology practice was bought by a hospital, its former chief operating officer likened the movement of doctors to “a migration of wildebeests.”33 One consequence of the migration was that cardiologists generated few balance bills. On the flip side, taxpayers ended up paying more to buy the same services, provided by the same physicians.

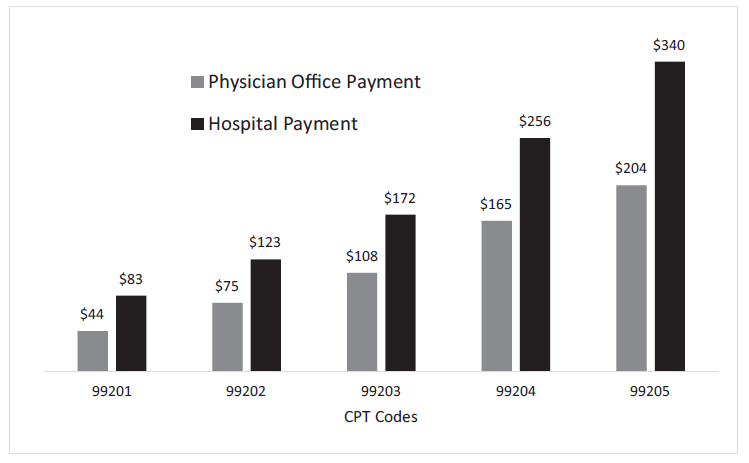

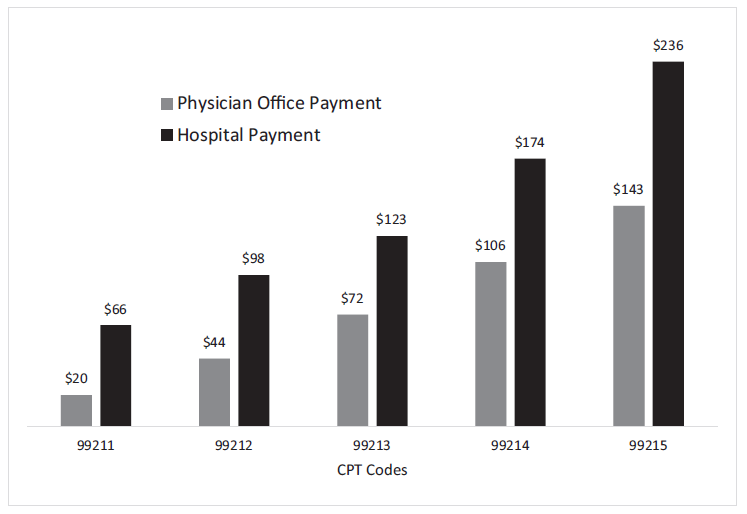

Site-of-service differentials exist for many medical treatments. In 2013, Medical Economics published a table showing site-of-service differentials for many routine visits to doctors’ offices, also known as “evaluation and management services.”34 As shown in Figures 9-1 and 9-2, in every instance, the payments for hospital-based treatments were higher—often much higher—than when doctors performed these services independently.

There are also site-of-service differentials for cancer drugs. When a hospital gives a lung cancer patient a dose of Alimta, its fee is about $4,300 larger than a doctor with an independent practice would receive. For Herceptin, a drug given to women with breast cancer, the site-of-service differential is about $2,600. And for Avastin, when used to treat colon cancer, it is $7,500.35 These site-of-service payment differentials help explain why hospitals have found it advantageous to bring cancer doctors in-house.36

Figure 9-1. Medicare Payments for Identically Coded Evaluation and Management Services at Physicians’ Offices vs. Hospital Outpatient Departments, New Patients (2013)

Source: Tammy Worth, “Hospital Facility Fees: Why Cost May Give Independent Physicians an Edge,” Medical Economics, August 6, 2014, http://medicaleconomics.modernmedicine.com/medical-economics/content/tags/facility-fees/hospital-facilityfees-why-cost-may-give-independent-ph?page=full.

Note: CPT 5 Current Procedural Terminology.

The American Hospital Association and other industry groups contend that site-of-service differentials reflect hospitals’ costs, which are higher than those of doctors in independent practice. That might be true in some instances. But, given that the same services are being provided in both settings, why are patients being treated at high-cost hospitals instead of low-cost doctors’ offices in the first place? If patients were spending their own dollars, they wouldn’t go to more expensive providers when cheaper ones were available, and just as good.

The American Hospital Association’s argument also fails to explain why the higher rates apply when doctors who sell their practices to hospitals keep on seeing patients at their old locations. When that happens, the costs of providing those services don’t change at all.

Figure 9-2. Medicare Payments for Identically Coded Evaluation and Management Services at Physicians’ Offices vs. Hospital Outpatient Departments, Existing Patients (2013)

Source: Tammy Worth, “Hospital Facility Fees: Why Cost May Give Independent Physicians an Edge,” Medical Economics, August 6, 2014, http://medicaleconomics.modernmedicine.com/medical-economics/content/tags/facility-fees/hospital-facilityfees-why-cost-may-give-independent-ph?page=full.

Note: CPT 5 Current Procedural Terminology.

Imagine you’re a Medicare patient, and you go to your doctor for an ultrasound of your heart one month. Medicare pays your doctor’s office $189, and you pay about 20 percent of that bill as a copayment.

Then, the next month, your doctor’s practice has been bought by the local hospital. You go to the same building and get the same test from the same doctor, but suddenly the price has shot up to $453, as has your share of the bill. . . .

Medicare . . . pays one price to independent doctors and another to doctors who work for large health systems—even if they are performing the exact same service in the exact same place.37

Gary Ziomek learned that location matters when he went in for physical therapy after spinal fusion surgery. The Charlotte Observer reports that Ziomek’s bill for a half-hour massage treatment was initially $148. But after his provider “began billing as a hospital-based setting” the price rose to $249.30—“even though he got the same therapy from the same therapist in the same building.” Ziomek was stuck with a larger fraction of the higher bill too. Instead of a $20 copay for an office visit, the encounter occurred in a “hospital-based setting,” so he had to meet a $250 deductible and cover 10 percent of the higher price.38

We are not aware of any site-of-service differentials that would induce hospitals to bring ER doctors, surgeons, or anesthesiologists in-house. Because there is no incentive for hospitals to hire these physicians as employees, they remain independent and outside of hospitals’ networks. That’s why they generate surprise bills.

Before leaving site-of-service differentials, we note that, after being pressured by many sources for many years, Congress finally took steps to eliminate them in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA). But Congress exempted existing physician employment relationships and hospital outpatient departments from the new payment policy.”39 In other words, site-of-service differentials for providers who were already billing through hospitals before the BBA took effect will continue indefinitely—even though everyone involved recognizes that they are inappropriate. Even when health care providers lose, they win.

REFER THEM TO ME

Hospitals make money by treating patients. But, except when patients show up at their emergency rooms, they don’t deal with patients directly. They rely on physicians to send them patients who need treatments that are delivered on the hospital’s premises. Cardiac surgery and interventional cardiology generate large revenue streams for hospitals, but the doctors who diagnose patients with heart problems are often noninterventional cardiologists. To stay profitable, hospitals need these noninterventional cardiologists to send patients to the hospital where they can be treated, whether in the operating room or cath lab.

When doctors practice independently, anti-kickback laws limit what hospitals can do to reward them for referring patients. They cannot pay for referrals, whether directly or indirectly. But nothing prevents hospitals from ensuring future patient flows by hiring doctors or acquiring their practices and paying them handsomely. So that is what hospitals do. Once that happens, doctors send their patients to the affiliated hospitals for care.

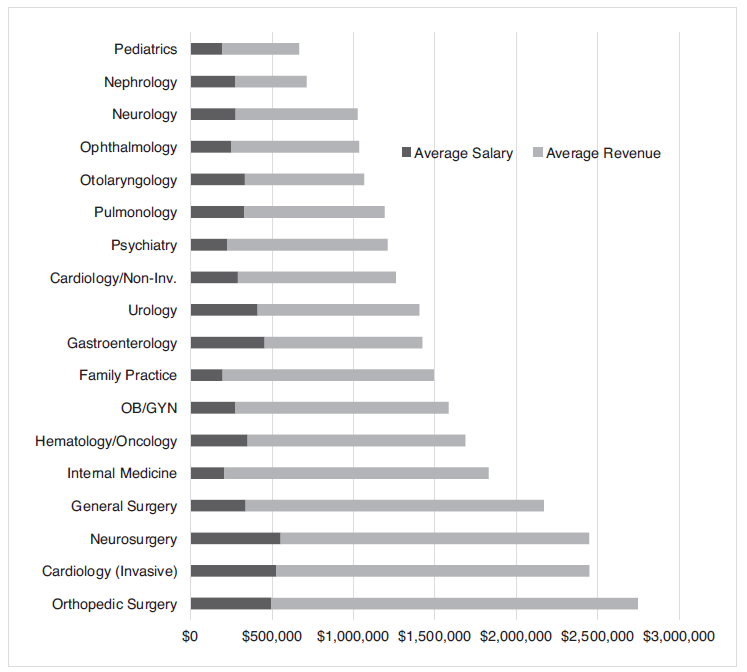

These employment relationships can have huge benefits for hospitals. Figure 9-3 shows the salaries that hospital-employed doctors draw versus the revenues they generate for the hospital.

On average, hospitals pay physicians 22 percent of the revenue they generate. Of course, the difference is not all profit, but it is clear that “physicians typically generate considerably more in ‘downstream revenue’ than they receive in the form of salaries or income guarantees.”40 And the surplus keeps rising. For all practice areas combined, the average net revenue in 2016 was $1,560,688, an increase of 7.7 percent over 2013. For specialty-care physicians, the increase was 12.8 percent.

Notice that Figure 9-3 does not include certain specialties. Anesthesiologists, radiologists, and pathologists are all missing, as are doctors who work in hospitals’ ERs. That’s because hospitals tend to treat these doctors as independent contractors, not employees. What do these disparate practice areas have in common? They do not refer many patients.

Neither anesthesiologists, nor radiologists, nor pathologists tend to have long-term relationships with patients. They are secondary members of teams that include other physicians whose relationships with patients are more direct. Because they do not bring patients to hospitals’ doorsteps, hospitals have little to gain by hiring them as employees.

Emergency medicine physicians are in the same boat. Patients don’t pick which ER to go to because they know the doctors that practice there. They go to the closest or most convenient ER. For everyone but ER frequent-flyers, the visit to the ER is the first and last time these patients and physicians will meet. Any patient in the ER who needs to be hospitalized will be admitted to the hospital the ER is located in. For these reasons, hospitals can increase their patient volumes by having ERs, but they cannot gain referrals by bringing emergency medicine physicians in-house. (In fact, as we discuss further below, hospitals that contract with some ER staffing companies make more money by treating ER doctors as contractors.)

Figure 9-3. Physician-Generated Revenue vs. Average Salaries

Source: Merritt Hawkins, “2016 Physician Inpatient/Outpatient Revenue Survey,” 2016, https://www.merritthawkins.com/uploadedFiles/MerrittHawkins/Surveys/Merritt_Hawkins-2016_RevSurvey.pdf.

THE ROOT CAUSE: PROVIDERS DON’T HAVE TO COMPETE FOR PATIENTS

The discussions of site-of-service differentials and referrals support a straightforward conclusion: balance billing continues to be a problem because neither doctors nor hospitals have a financial interest in ending the practice. A few exceptional hospitals do require all doctors to belong to the same insurance networks that they do, showing that hospitals could solve this problem if they wanted. But other hospitals haven’t followed their lead because they see no upside to bringing in-house the doctors who send out balance bills. They cannot gain referrals or site-of-service differentials by doing so.

This is remarkable. Hospitals see no advantage in protecting patients from surprise bills, even though the bills worry patients greatly and saddle many of them with significant costs. In a competitive market, a seller that found a way to protect its customers from a significant financial risk to which other sellers deliberately left them exposed would advertise the fact and be rewarded with new business. Other sellers would then copy the innovation and offer it to their customers too, for fear of suffering financially if they didn’t. In short order, most or all consumers would be protected. But hospitals don’t compete for customers in free markets, so they worry much less than they should about attracting patients by adopting desirable innovations and about losing patients to innovative competitors. Surprise bills are a consequence of a lack of market competition.

The body shop that keeps your car in good repair would never think of letting one of its mechanics send out a surprise bill. It has to be customer friendly, so it packages all of the services it provides into a single bill and charges a competitive price. The body shop that keeps you running could do the same. It could require all of the providers who deliver services at its facilities to bill through its offices at rates that are acceptable to patients. It doesn’t do that because it is confident that patients will keep coming through its doors, regardless of surprise bills.

The same goes for doctors who send out surprise bills. ER physicians, anesthesiologists, pathologists, and radiologists don’t have to compete for patients. They merely need access to hospitals with reliable patient flows. They don’t have to be patient friendly either, so they aren’t.

What about insurers? Can’t they solve this problem by getting doctors to join their networks? Unfortunately, they can’t. Physicians join networks because they need the business that insured patients provide. But the doctors who are responsible for the most surprise bills know that they will have plenty of customers whether they join insurers’ networks or not. Consequently, insurers have little leverage over them.

These doctors also know that they’ll collect some money from insurers, whether they join insurers’ networks or not. Surprise bills are balance bills—they’re bills that patients receive after the insurance company has already paid the doctor. Given this, the strategy of staying outside of insurers’ networks is more profitable for these physicians. By joining a network, they would limit themselves to the insurance dollars alone. As long as they stay outside, though, they can collect the insurance money plus whatever additional dollars they can extract from patients through surprise bills.

Doctors would be much less likely to play this game if they knew they’d lose patients. The need to compete would temper their zeal to send out surprise bills. But they know that our competition-stifling, government-controlled payment system will direct patients to them regardless, so their enthusiasm for surprise bills is effectively unrestrained.

HOW UNIFORM IS SURPRISE BILLING?

A recent large study of surprise bills makes it clear that the phenomenon is driven by the desire for profit. Out-of-network ER doctors charge far more than in-network physicians do for identical services. They also charge more than six times what Medicare pays.41

But the study also found that the frequency with which patients received surprise bills varies widely. Although 22 percent of patients treated at ERs were hit with surprise bills on average, at some hospitals, most or essentially all patients were. “At about 15% of the hospitals, out-of-network rates were over 80 percent.”42

Much of the variation is explained by the business models of the companies that hospitals engage to manage their ERs. At hospitals that outsourced their ERs to EmCare, one of the two largest outfits in the United States, both charges for services and the frequency of surprise bills increased. “[W]hen EmCare—which has an average out-of-network billing rate of 62%—takes over the management of emergency services at hospitals with low out-of-network rates, they raise out-of-network rates by over 81 percentage points and [increase] average physician payments by 117%.”43

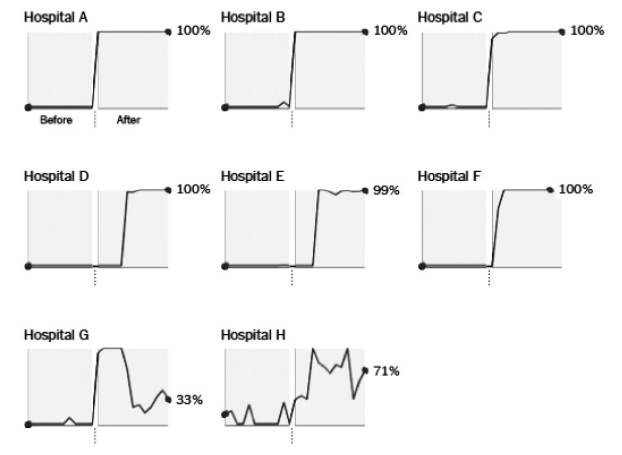

Figure 9-4 shows what happened to the rates at which eight hospitals sent out-of-network bills after those hospitals hired EmCare to manage their ERs. At each hospital, the frequency of balance bills increased quickly and markedly, often rising from a low level to 100 percent. One of the authors of the study, which relied on data provided by an insurer, aptly described the change in billing practices as looking “like a light switch was being flipped on.”44

Why did hospitals allow this to happen to patients treated in their ERs? One obvious reason is that they too made money on the deal. After EmCare took over, hospitals’ fees increased significantly, owing to more intensive treatments and higher admission rates. In effect, EmCare paid hospitals for the opportunity to balance bill their patients.

Figure 9-4. Change in Out-of-Network Charges following Changes in Emergency Room Management

Source: Zack Cooper, Fiona Scott Morton, and Nathan Shekita, “Surprise! Out-of-Network Billing for Emergency Care in the United States,” NBER Working Paper no. 23623, July 2017, National Bureau of Economic Research, Figure 3.

When the results just described made nationwide news, how did EmCare respond? It reportedly claimed that hospitals can “treat sicker patients when it takes over, and . . . an increase in such patients explain[s] the higher billing.”45 The Reverse Lake Wobegon Effect strikes again.

THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK

We close with a case study that brings together many of the pathologies we discuss in this chapter. In Texas, balance billing has been a particular problem with freestanding emergency departments. These facilities look like urgent care centers, but they are almost never in-network for health insurers. And they bill at rates that are reported to be 10 times those of urgent care centers. When an insurer denies payment of the excess amount, the patient who was treated is on the hook for the balance.

In 2017, researchers associated with Rice University, the Baylor College of Medicine, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, and Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas published a study of ER charges in the Annals of Emergency Medicine. They examined more than 16 million insurance claims processed from 2012 to 2015. Their object was “to track the growth in use and prices for freestanding emergency departments relative to hospital-based emergency departments and urgent care centers in Texas.”46 The project was interesting partly because many people think that freestanding ERs and urgent care centers are the same. Both are typically located in neighborhood shopping centers, so how different can they be?

Very different, judging from their bills. The average charge for a freestanding ER visit ($2,199) was about the same as for a hospital-based ER visit ($2,259) but a whopping 13 times the average charge for an urgent care center visit ($168).47 A patient who visits a freestanding ER expecting an urgent care center charge is in for a nasty surprise.

The prospect of paying substantially more at a freestanding ER seems especially galling when one realizes that these facilities often deliver the same treatments as urgent care centers to patients with the same conditions.

Fifteen of the 20 most common diagnoses treated at freestanding emergency departments were also in the top 20 for urgent care clinics. However, prices for patients with the same diagnosis were on average almost 10 times higher at freestanding emergency departments relative to urgent care clinics. For example, the most common diagnostic category treated at freestanding emergency departments is “other upper-respiratory infections,” which has an average price of $1,351, more than eight times the price of $165 that was paid for the same diagnosis at urgent care clinics.

Thirteen of the most common procedure codes associated with freestanding emergency departments were also among the 20 most common for urgent care clinics. In cases in which the type of procedure overlapped, the total price per visit was 13 times higher in freestanding emergency departments versus urgent care clinics. For example, the price for a therapeutic or intravenous injection at a freestanding emergency department was $203, which was 11.9 times the $17 price at an urgent care clinic.48

These staggering price differences could not exist in competitive markets with informed shoppers who were responsible for their bills. Consumers with minor problems would quickly learn that urgent care centers are much better bargains and would stop frequenting freestanding ERs. In fact, however, freestanding ER usage “rose by 236 percent between 2012 and 2015.”

These findings provide more evidence that we pay for health care the wrong way. Patients aren’t shopping intelligently. They aren’t asking about prices or seeking out good values, probably because they’re accustomed to relying on their insurers to handle the finances. With time, this may change. As more and more people who visit freestanding ERs get stuck with surprise bills, the focus on costs should intensify and patients who have time to look around will take their business to lower-cost providers. Urgent care centers also have every incentive to advertise the sizable savings they offer by comparison to freestanding ERs.

These findings described above did not sit well with the doctors and business executives who run freestanding ERs. After the study appeared, Dr. Paul Kivela, president-elect of the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), called Vivian Ho, the lead author. He reportedly “complain[ed] about some numbers in an appendix and implied [that] she could be sued.”49 Then the Annals of Emergency Medicine “pulled the study for further review.”50 Although the reason given for taking this step was “‘serious concerns over data in the article,” the backstory appears to be that the ACEP runs the Annals and its member doctors were unhappy that their organization’s journal published a study that cast their business model in a bad light. That’s Dr. Ho’s view, at any rate. She said the ACEP “controls the journal, and they are receiving complaints from emergency physicians, particularly those who could earn a substantial share of their income from the freestanding ER model.”51 She admitted that a minor transcription error occurred in the course of preparing the article for publication, but “said the study findings should stand, once corrected.”52

The damage inflicted on the reputations of Dr. Ho and her colleagues was partially repaired when the Annals reposted the study in late 2017.53 But the republication was accompanied by a series of letters, policy statements, and other writings in which the researchers’ data, findings, and integrity were questioned.54 The lesson for academics? Study the financial side of health care delivery at your peril because providers whose revenues are at stake may rough you up.

If health care was provided in a competitive market, free-standing ERs would either charge the same prices that urgent care centers do for the same services or they would be out of business. There would be no more need to study freestanding ERs’ charges than there is to study the prices charged by Best Buy or Dell. Stated differently, if we want to fix the problem of balance billing, the most direct solution is to reward providers that protect their patients from the risk of receiving surprise bills. And, the best way to do that is to enable cost-conscious consumers to shop for value.

Balance billing is a problem that providers can fix, and would fix, if it were in their interest to do so. But surely the protection of the vulnerable is a job for the government, particularly when people are elderly and dying, right? If you think the government can be relied on to take care of these people, the next chapter will force you to think again.