CHAPTER 15: HEALTH CARE IS EXPENSIVE BECAUSE IT’S INSURED

THIRD-PARTY PAYERS DON’T CARE ABOUT YOU

Third-party payers dominate health care. Like Medicare and Medicaid, some of these payers are public, while others—including insurers like UnitedHealth Group, Anthem, Aetna, Humana, Cigna, and the many Blue Cross/Blue Shield companies—are private. Public payers are political operations, so they naturally care about political things, like maximizing their budgets and keeping members of Congress happy. Private payers are like other businesses. They want to maximize their profits. These are not criticisms. Government agencies are supposed to care about politics, and businesses are supposed to care about their finances.

But there is a deeper point. Helping patients and consumers isn’t the top priority for third-party payers of either type. This goal matters to them only when, by pursuing it, they can get what they really want: money, bigger budgets, reelection, or something else they care about. Unfortunately, helping patients and consumers only occasionally makes payers better off. Payers rarely care about the well-being of patients or consumers.

To see why, start with Point #1: Payers want health care to be expensive. The reason is simple. If medical services were cheap, we wouldn’t need Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurers to bear the cost for us. In 2016, the median family with two adults and two children spent almost $17,000 on housing and about $8,300 on transportation, without any help from insurance companies.1 If medical services predictably cost only a similar amount each year, people could pay for them directly too. This would make consumers and patients happy, but third-party payers would be sad. The need to route more than $1 trillion through the Medicare and Medicaid programs would vanish. The need for private insurers would diminish too.

We can’t expect Medicare, Medicaid, or private carriers to put themselves out of business. Rick Scott, the governor of Florida and the former CEO of a scandal-plagued health care company, hit the nail on the head when he asked, “How many businesses do you know that want to cut their revenue in half?”2 None. “That’s why the health care system won’t change the health care system,” Governor Scott rightly concluded.3

If you’ve grasped Point #1, you should find it easy to understand Point #2: The more expensive health care becomes, the happier payers are. The more medical services cost, the more people will want the protection from risk that Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers provide. Suppose that all of the services a person might reasonably expect to need in an emergency—everything from transportation by ambulance through postsurgery rehabilitation—could be had for $1,500. Spending money on health care is never fun, but many people could afford to bear the risk of having to spend $1,500 themselves. Many people with insurance have deductibles larger than that, and a deductible is just a provision for direct payment.4 But if an emergency were likely to generate costs in the $15,000 range—ten times as much—insurance would be much more attractive. Many people would think it indispensable. And pretty much everyone would reach that conclusion if the expected cost of emergency medical care was $150,000, an amount that only the super rich could afford to pay out of pocket. The more health care costs, the more consumers will want the protection from risk that third-party payers offer.

Expensive health care also directly benefits the politicians, political appointees, and career bureaucrats who are in charge of Medicare and Medicaid, including the members of Congress who trade influence for political contributions and other support. They want the budgets for these programs to be as large as possible. Bigger budgets mean greater power and more goodies to dole out. Insurance executives also prefer larger companies to smaller ones. These business titans care mainly about their compensation, and the size of executives’ pay packages correlates strongly with the size of the companies that employ them.5

Because expensive health care makes third-party payers’ services essential, their business model depends on fear. They need patients and consumers to be terrified that health care expenses will ruin them. Consequently, they won’t work to change the system in ways that would put consumers at ease.

A VICIOUS CYCLE

Until the second half of the 20th century, doctors and hospitals opposed the government’s efforts to stick its nose into their business. Although few people alive today know the history, organized medicine bitterly opposed the creation of Medicare. Dr. Donovan Ward, the head of the American Medical Association (AMA), declared that “a deterioration in the quality of care is inescapable.” Similarly, the president of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons stated that it would be “complicity in evil” for doctors to participate in Medicare.6 The AMA even hired Ronald Reagan to read a speech on the threat that socialized medicine posed to the American way of life and sent copies of the recording to every doctor’s office in the United States.7

Today, doctors are Medicare and Medicaid’s biggest fans. Opposition morphed into support when they realized that, with the government footing the bills, they could raise their rates—which they immediately did. As Harvard economist Martin Feldstein observed way back in 1970, “after [the] introduction of Medicare and Medicaid, physicians’ fees rose at 6.8 per cent per year in 1967 and 1968 in comparison to a 3.2 per cent annual rise in the [consumer price index].”8 Government programs put money in doctors’ pockets, so organized medicine did a 180-degree turn.

Physicians should have guessed that government-run third-party payment arrangements would make them rich. From 1945 to 1965, the fraction of the U.S. population with some form of health care coverage more than tripled, rising from 22.6 percent to 72.5 percent.9 Doctors benefited enormously. Their charges rose at 1.7 times the rate of inflation. As Professor Feldstein dryly observed, “There appears to be a tendency [on the part of physicians] to increase prices when patients’ ability to pay improves through higher income or more complete insurance coverage.”10

The effect of insurance on hospitals’ charges was even more pronounced. Again, Feldstein did the pioneering research. He opened The Rising Cost of Hospital Care by observing that “A day of hospital care in 1970 cost . . . five times as much as in 1950”—a staggering increase, especially because “the general price level of consumer goods and services [rose] less than 60%” over the same period. From 1966 to 1970, the last five years Feldstein studied, hospital prices rose annually by almost 15 percent. Why? The main driver was the growing availability and generosity of public and private insurance.11

Over the two decades Feldstein studied, the fraction of hospital care paid for by some form of insurance rose markedly. In 1950, the split between insurance and patient responsibility was roughly 50–50. If a hospital day cost $600, the insurer paid $300 and the patient paid $300. By 1968, insurers were picking up 84 percent of the cost.12 This meant that, at $600 per day, the insurer paid $504 and the patient only $96.

The shift of financial responsibility to insurers was so dramatic that patients actually paid less even as hospitals raised their rates. Suppose that, from 1950 to 1968, the cost of a hospital day trebled, from $600 to $1,800. In 1950, the patient’s share would have been $300. In 1968, it would have been only $288. As wages rose and people became wealthier, hospital care seemed like a better bargain than ever, because more and more of its cost was being borne by insurers.

The portion of hospital spending borne by public and private third-party payers kept increasing throughout the 20th century, and total health care spending rose right along with it. In recent research, Amy Finkelstein, a professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, estimated that the spread of insurance was responsible for about half of the six-fold increase in real health care spending per capita that occurred from 1950 to 1990.13 In other words, insurance caused health care spending to triple. From 1965 to 1970 alone, Medicare drove up real outlays on hospital services by 37 percent. Similar increases were found across all age groups. When insurance inflates demand, prices rise across the board and everyone suffers.

THE EVIL GENIUS OF INSURANCE: MAKE HEALTH CARE CHEAP AT THE POINT OF SALE

It’s easy to see why insurance stimulates demand. At the point of sale, people don’t spend their own money. This makes medical services seem cheap or even free, so people naturally want more of them. And, just as naturally, they care very little about the total cost of the services they use.

The average price of a total knee replacement is about $31,000.14 That’s about what you’d pay for a new Audi Q3, a small luxury crossover SUV. But the average patient who undergoes a knee replacement pays less than 10 percent of the total, say, $3,000. The rest is covered by insurance. If the same arrangement existed in the auto market—call it “new car insurance”—you could buy a $31,000 Audi Q3 for $3,000. So you’d happily take one—or maybe several—even if you would never pay $31,000 out-of-pocket for this particular car.

Insurance generates demand for medical treatments in the same way. You pay a monthly premium over which you have little control, often because the dollars are withheld from your salary. And, once that money is spent on insurance, it isn’t coming back, whether or not you actually use any health care. However, you do get to decide whether to have knee replacement surgery or not. The evil genius of health insurance is that, at the point of delivery, it encourages patients to overconsume by making medical services seem cheap. Financially, your knee replacement surgery is the equivalent of a $3,000 Audi Q3. Even if you would never spend $31,000 of your own money on a knee replacement, as long as you value the benefits of the procedure more than $3,000—which is far less than its actual cost—you will willingly go under the knife. And the price stays high because few consumers shop for bargains or refuse knee surgery because of the price.

What’s true for you is also true for the millions of other people who carry insurance. You get to buy an Audi Q3 for $3,000 and so do they. Over time, the country will be flooded with new Audis and all of these new Audi owners will impoverish each other. Premiums will have to rise, because the money to pay for all the new Audis has to come from somewhere. Finally, as insurance-driven demand for Audis increases, Audi will increase its prices and aggregate spending will go through the roof.

The problem just described exemplifies what social scientists call a “prisoners’ dilemma.” Millions of people do something—here, buy insurance that heavily subsidizes medical services at the point of sale—that they think will make each of them better off. But collectively they wind up worse off than they would have been if they had each paid for their own health care. Without insurance, the only people who would have had knee surgery would have been those willing to pay $31,000 for it, just as in real life, the only people who buy Audi Q3s are those willing to part with the same amount of cash. Demand would have been much lower, and prices would have been too.

STUDIES OF INSURANCE-INDUCED DEMAND

Insurance without a significant point-of-service copayment will inflate the demand for medical services. The total cost of a doctor’s office visit might be $200, but an insured person who parts with only the $30 copay won’t care. He or she will visit the doctor whenever it’s worth spending $30 to do so, even if the value doesn’t approach $200.

Doctors understand this, as a recent dispute from Down Under makes clear. Hoping to rein in spiraling costs, a commission appointed by the Australian government raised the possibility of imposing a $6 copay for visits to doctors’ offices. Six dollars doesn’t sound like much, but it was a large increase from the prior copay—$0. Retirees would have been exempt from the charge, and families would have had to pay it only after seeing a doctor 12 times a year. Despite the trivial size of the copay and the exemptions, the Australian Medical Association condemned the proposal. Why? Because any charge, even a small one, would cause people to see their doctors less often.15

In the language of economics, the Australian Medical Association recognized that demand for medical services is elastic. Demand falls when prices rise, and it rises when prices fall. If a patient’s cost at the point of service went from $0 to $6, some patients who would gladly consume free medical services would stay home. They would regard their health concerns as being too minor to spend $6 on. Their doctors would then lose the much larger payments for these patients’ office visits that the government provides. Although the Australian Medical Association framed the issue around denial of necessary medical treatment, it was really just trying to preserve the flow of money to its members.

Not all medical services are like office visits, though. Consider joint replacement surgery, which we discussed above. The pain, loss of time, and required postoperative physical therapy should discourage anyone from having a knee replaced on a whim. Can the decision to have surgery really be analyzed in the same terms as the decision to buy a car? And what about medical procedures that aren’t discretionary, such as emergency surgery for a gunshot wound? Isn’t demand sometimes fixed, instead of price dependent?

Absolutely. There are thousands of medical procedures, and the elasticity of demand surely varies across them. But discretionary calls occur often, so there is enough elasticity for insurance to increase health care consumption and spending substantially.

Clever studies have examined the impact of insurance on health care consumption.16 Several papers focus on Oregon’s decision to expand Medicaid in 2008. Oregon allowed anyone who met the eligibility criteria to apply, but it received far more applications than it could accept. So it randomly chose a subset of applicants to receive Medicaid coverage. This created a natural experiment, that is, an especially good opportunity to study the impact of insurance on health care utilization. Because the applicants who received Medicaid (the “winners”) were chosen at random from the same pool as those who did not (the “losers”), any differences in health care utilization between these two groups could be chalked up to insurance.

The first article from the Oregon experiment in the medical literature appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2013.17 The researchers determined that “Medicaid coverage increased annual medical spending . . . by $1,172” per household. In other words, the winners used about 35 percent more medical services than the losers. Having Medicaid coverage made only a modest difference in the winners’ health, however, although it did reduce financial strain.

A follow-up article examined emergency room usage. Remember the sales pitch for Obamacare? It was supposed to save money because insured people and people covered by Medicaid would see cheaper primary care physicians instead of getting basic medical care at more expensive emergency rooms. That’s not what happened in Oregon. The winners used emergency rooms 40 percent more often than the losers did. The increase was for “a broad range of types of visits, conditions, and subgroups, including increases in visits for conditions that may be most readily treatable in primary care settings.”18 When people are insured, they use all types of medical services more often. A subsequent article on the Oregon experiment reevaluated the earlier findings using an additional year of data. The results were the same. “Newly insured people will most likely use more health care across settings—including the [emergency room] and the hospital.”19

Another clever study focused on senior citizens and evaluated the impact of qualifying for Medicare on health care utilization.20 It compared people ages 62–64 to people who were 65. Because the two groups were so close in age, the health status of their members was similar. One might have expected the slightly older group to use a bit more medical care per person, but not much. In fact, hospitalizations, visits to doctors’ offices, and the use of prescription meds all spiked at age 65. Why? Because that’s when people become eligible for Medicare. The older people used lots of Medicare-financed health care that the people in the 62-to-64-year-old bracket, many of whom lacked insurance, wouldn’t (or couldn’t) pay for themselves. It is hard to come up with better evidence that the demand for medical treatments is, in fact, quite elastic.

In sum, third-party payment and the cost of health care feed on each other. Back in the 1940s, far fewer people were insured. Consequently, most health care was paid for out of pocket. This kept health care affordable. Then employer-sponsored health care became common, which stimulated demand and caused spending to rise. In the mid-1960s, Medicare and Medicaid extended coverage to tens of millions of additional people, and demand for health care went through the roof. Because supply was limited and third-party payers were footing the bills, prices rose accordingly. This stimulated the demand for insurance even more, triggering greater consumption of medical services, higher prices, and—again—increased demand for insurance.

Feldstein, the Harvard economist, described the cycle more than 40 years ago:

The price and type of health services that are available to any individual reflect the extent of health insurance among other members of the community. . . . [P]hysicians raise their fees (and may improve their services) when insurance becomes more extensive. Nonprofit hospitals also respond to the growth of insurance by increasing the sophistication and price of their product. . . . Thus, even the un-insured individual will find that his expenditure on health services is affected by the insurance of others. Moreover, the higher price of physician and hospital services encourages more extensive use of insurance. For the community as a whole, therefore, the spread of insurance causes higher prices and more sophisticated services which in turn cause a further increase in insurance. People spend more on health because they are insured and buy more insurance because of the high cost of health care.21 (emphasis added)

As we explained above, the vicious cycle works through fear, and also by making medical services free, or nearly so, at the point of delivery. Remember the $3,000 Audis? The more we route payments through third-party payers, the less we bear the real cost of services at the point of delivery and the more we consume.

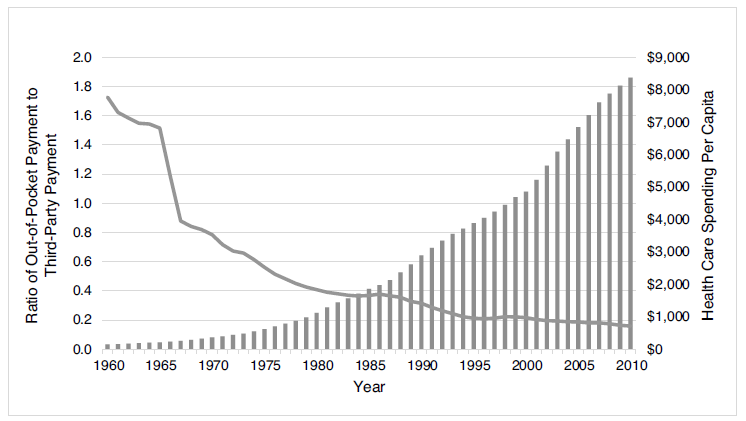

The connection between third-party payment and health care spending will be obvious to anyone who bothers to look. In Figure 15-1, the line shows the ratio between the amounts that consumers paid directly for health care and the amounts that were spent by Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers (left-side axis). The line starts out at about 1.80, meaning that in 1960 consumers paid $1.80 out of pocket for every dollar spent on medical services by a third-party payer. Then it declines steadily, so that, by 2010, for every dollar a payer shelled out, a consumer spent less than 20 cents. The decline in direct, personal financial responsibility was especially pronounced in the mid-1960s, when Medicare and Medicaid were introduced. The vertical bars show annual health care spending per capita (right-side axis). It rises from a few hundred dollars in 1960 to over $8,000 per person in 2010. As direct payment falls, per capita spending rises. The more heavily we rely on third-party payers, the more we spend.

Figure 15-1. The Less We Rely on Ourselves, the More We Spend: Relationship between Direct Financial Responsibility for Medical Expenditures and Per Capita Health Spending

Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “National Health Expenditures by Type of Service and Source of Funds: Calendar Years 1960 to 2015,” available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html.

OBAMA VS. STEIN

Herbert Stein, another prominent economist, is credited with coining Stein’s Law: “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.” The vicious cycle described by Feldstein is no exception. Its eventual end is assured. As insurance-induced demand makes medical services more expensive, the price of insurance has to rise. As coverage costs more, employers will be more reluctant to offer it as a benefit and people will be less eager to buy it on their own. Over time, rising prices for health care will slow, stop, and perhaps even reverse the spread of insurance. As the pool of insured consumers starts to shrink, demand for medical services will weaken and the flow of money into the health care sector will grow less quickly than before.

The tipping point that signaled the end of the cycle appears to have been reached at the start of this century. That’s when private coverage took a nosedive. From 2000 to 2010, the number of people with private insurance fell from 205.5 million to 196 million.22 Because the U.S. population grew steadily over that period, the number (and share) of the uninsured increased dramatically. In 2000, about 13 percent of Americans lacked insurance coverage. In 2010, about 16 percent did.23 In raw numbers, by the end of the decade, 50 million people were uninsured.24

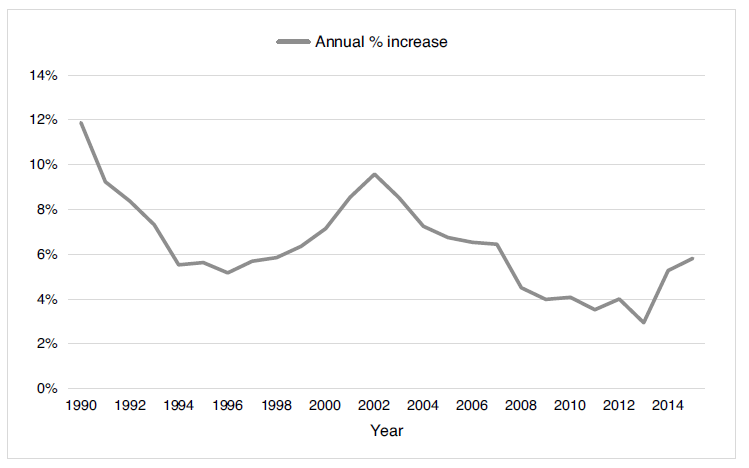

The result is shown in Figure 15-2.25 From 2002 to 2011, the annual rate of increase in health care spending steadily declined. In 2002, Americans spent almost 10 percent more on medical services than they did in 2001. From 2009 to 2012, the year-over-year increase was less than 4 percent.

The declining generosity of employer-provided coverage contributed to this trend. Workers who managed to hold onto their health care coverage in the 2000s found that the terms of coverage were less generous. Especially during the financial crisis, when businesses of all sorts struggled to make ends meet, insured workers found that they were picking up more and more of the costs of medical services through copays, deductibles, and annual payment limits. According to one estimate, “rising out-of-pocket payments . . . account[ed] for approximately 20 percent of the observed slowdown” in the growth of health care spending.26 In combination, the increase in the share of health care spending that had to be paid for out of pocket and the Great Recession made consumers more cautious about throwing additional money at health care providers.

Figure 15-2. Yearly Increase in Total National Health Expenditures (1990–2015)

Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “National Health Expenditures by Type of Service and Source of Funds: Calendar Years 1960 to 2015,” available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html.

From the perspective of the American health care system, which takes for granted that the flow of money will constantly increase, declining growth rates were intolerable. From the perspective of academic health policy experts, the decline in the number of insured was a calamity too. The experts equate insurance with access to medical services, and they equate medical services with good health. That is why both the industry and the academics are big fans of Obamacare, which sought to require all 50 million uninsured Americans to obtain coverage or participate in Medicaid. Forcing 50 million Americans to use third-party payment arrangements would have helped restore the vicious cycle, at least for a while. Once covered, the newly insured would demand even more health care, causing the growth in health care spending to resume its rapid rise and driving more dollars to health care providers.

Seen in this light, Obamacare was a ticket to more years of sizable spending increases. That’s why “drugmakers, insurers and hospitals . . . helped bankroll the law. . . . Big business . . . agree[d] to various taxes, fees and reimbursement cuts, and it expects to see a return on investment as newly insured people use its products and services.”27 Health care providers needed new customers. They got millions of them by supporting Obamacare. The insurance mandate, which required people to carry insurance or pay a fine, was the key to keeping the party going. Yogi Berra once quipped, “If people don’t want to come out to the ball park, nobody’s gonna stop ’em.” Obamacare showed that the government could stop people from staying home and force them to go to the game.

And, once everyone got there, they were given health insurance with all the bells and whistles. As of 2014, health insurance plans had to take everyone, including people known to have health problems that require expensive treatments. They also had to provide unlimited benefits. An individual who needed $5 million a year in health care would get it. After all, it was somebody else’s money—and it could be used to buy almost anything imaginable. Obamacare required insurers to cover ambulatory services, emergency services, hospital care, maternity and newborn care, mental health and substance abuse counseling, prescription drugs, rehabilitative services and devices, laboratory services, preventive and wellness services, chronic disease management, and pediatric services. And the list could always be broadened to accommodate any important constituency, as it was when women and providers complained about the omission of routine mammograms. Obamacare was a smorgasbord, and the menu would predictably become richer and more varied over time as Congress pandered to special interests.

Obamacare also used generous subsidies to help keep the cycle going. The subsidies came in two forms. Premium tax credits for people with incomes up to $97,000 for a family of four ensured that monthly insurance premiums would not exceed specified levels, ranging from 2 percent to 9.5 percent of income. Cost-sharing reduction subsidies lowered insured patients’ out-of-pocket costs attributable to deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments for covered services.

Signs quickly emerged that Obamacare was also subject to Stein’s Law. As waves of people bought insurance and millions more enrolled in Medicaid, premiums started to rise and government spending increased substantially.28 The Obamacare exchanges attracted a population whose members were unusually sick. Many of them had previously been enrolled in states’ high-risk pools. Some had been denied coverage because of pre-existing conditions. As costs rose, insurers had to raise prices for everyone. This encouraged healthy people to drop their policies. And as they opted out, the pool of premium-payers shrank, became sicker on average, and led insurers to raise prices again. Regardless of who won the 2016 presidential race, the cycle would continue until Obamacare failed or Congress bailed everyone out by massively increasing the Obamacare subsidies.

Medicaid’s budget also ballooned. Writing in early 2016, Brian Blase, a researcher at George Mason University, observed, “No major area of federal spending has increased more dramatically since President Barack Obama took office than Medicaid.”29 From 2008 to 2015, total spending on Medicaid grew by 43 percent, or $168.2 billion. The growth had several drivers, including the Great Recession, which put millions of people into poverty, Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion, and the fact that new enrollees in Medicaid tended to use medical services in larger amounts. These increases would have been even larger had all 50 states expanded Medicaid, as Obamacare originally intended. Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion was primed to create fiscal havoc no matter who won the 2016 election.

INSURANCE MAKES MEDICINES MORE EXPENSIVE

Shortly after taking office, President Trump declared war on the pharma sector. Drug companies were “getting away with murder,” he said, and he threatened to allow Medicare to reduce drug costs by negotiating lower prices.30 Several pharma execs responded by promising to limit annual price hikes to 10 percent.

To the average American, whose wages have been stagnant for years, a promise to raise prices by “only” 10 percent must have sounded like a pledge to continue gouging. Why 10 percent instead of the rate of inflation, which was much lower? Why raise prices at all instead of cutting them? Most drugs on the market today were invented years ago. Apple can’t charge more for old iPhones. Ford can’t charge more for trucks built in prior model years. Why should pharma companies be able to charge more for last year’s drugs?

Some pharma execs disregarded the 10 percent pledge. Jeffrey Aronin, the CEO of Marathon Pharmaceuticals we met all the way back in Chapter 1, announced that his company would charge $89,000 a year for deflazacort, a treatment for muscular dystrophy that had long been available in other countries and that cost about $1,000. Marathon had gained a monopoly on U.S. sales of deflazacort by obtaining U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval for the medication under the Orphan Drug Act, and Aronin was bent on exploiting it.

When accused of price gouging, Aronin used a well-worn gambit to deflect criticism. He said that most of the money to pay for the drug wouldn’t come from patients—it would come from insurance companies. Aronin knew that most Americans hate insurance companies and wouldn’t care if drug makers ripped them off. They feel for patients, though, so it was important to emphasize that patients’ costs would remain the same.

Aronin was just trying to get the press off his back. But his comment brings an important issue to the surface. When a loss occurs, insurance is supposed to enable people to obtain certain goods and services that are too costly for them to afford. For example, few homeowners have enough money to rebuild a house that burns down. That is why most homeowners can and do protect themselves against the risk of fire by buying homeowners’ insurance. Health insurance has the same effect when people fall ill. It pays for expensive drugs that people might otherwise be unable to purchase. This is known as the liquidity benefit of insurance.

But insurance is not supposed to make the goods and services that policyholders require cost more, or to be the rationale for opportunistic price increases. The fact that an insurer rather than a homeowner is paying to rebuild a house should not affect the price of nails, wood, roofing shingles, or labor. Nor should the price of medications reflect the identity of the buyer. A drug that ordinarily sells for $1,000 shouldn’t fetch the absurd price of $89,000 just because a patient’s insurer, rather than the patient, is footing the bill. Price increases attributable to the identity of the buyer are part of the moral hazard effect of insurance.

There is a widely held impression that drug manufacturers do charge more for their products when insurers are on the hook. As three prominent professors at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management observed, “it is difficult to imagine that Gilead would charge anywhere near $84,000 for Sovaldi,” the breakthrough drug for hepatitis C, “were it not covered by insurance.” If that is right, they continued, “the existence of insurance for this product has clear implications for access and pricing.”31

The Kellogg researchers tested a model that, they hoped, would help them learn whether “the unprecedented high prices of new prescription drugs depended on the liquidity benefits of insurance,” whether consumers would be better off if these drugs were not insured, and whether insurance enabled pharma companies to charge more than new drugs were worth. Their data consisted of prices for oncology drugs before and after the creation of Medicare Part D—the prescription drug benefit—in 2003.

Their results reveal a sizable influence of insurance on drug prices. Among their many findings were “two reactions to the passage of Medicare Part D. First, the manufacturers of oral chemotherapy products increased their prices. Second, these manufacturers were now able to command prices that exceeded many estimates of the value that they create.” In short, “the passage of Part D is associated with a large increase in the average launch price of oncology products,” an increase that could not be justified on the basis of the tendency of these drugs to extend patients’ lives.32

One possible implication is that the prices insurers pay for drugs could exceed the value of those drugs to the patients who receive them. Of course, the prospect of charging high prices to insured patients may have motivated Gilead to develop Sovaldi too. We discuss the need for incentives to innovate in Chapter 19.

In theory, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), companies like ExpressScripts and ProCare RX that serve as intermediaries between drug makers, insurers, and pharmacies, could bargain prices down to competitive levels by offering manufacturers access to lots of customers. In fact, PBMs can and do exert downward pressure on prices. But there are also concerns that PBMs may gain by keeping drug list prices high (raising consumers’ copays),33 and by providing insurance coverage for prescriptions that would be cheaper were they purchased for cash. There are also allegations that PBMs are using “gag clauses” in their contracts with pharmacies to hide these facts from consumers.34

The real question is why we need PBMs at all. Patients who buy over-the-counter drugs pay low prices, and they do not deal with PBMs. In the retail sector, competition does all the work, for free. PBMs exist only because, by using insurance to pay for drugs instead of buying them directly, we have created a market niche for them.

Clearly, insurance is a gamechanger. It enables patients to acquire new drugs that they could not afford on their own and leads drug makers to strategize to maximize the dollars they collect from insurers. These opportunistic pricing strategies make insurance more expensive—possibly too expensive for many people to afford—and may even enable drug manufacturers to capture more value than they create. It also creates a need for PBMs to serve as middlemen—and no one likes middlemen.

The title of this chapter asserts that health care is expensive because it’s insured. That’s generally true, but not always. Some medical treatments would be expensive regardless. Everyone already knows that. What few people understand is that causation runs from insurance to cost too. Insurance makes health care more expensive than it would be if people paid for it themselves. Americans would purchase fewer medical treatments and would pay much less for them, if not for the existence and government encouragement of excessive insurance.